Montgomery Field (Carlsbad, NM)

This article was written by Kurt Blumenau

Pitcher Gordon Zabasky winds up on the mound at Montgomery Field, April 1957, in Carlsbad, New Mexico.

In the spring of 1984, the decaying remains of Montgomery Field – a former minor-league ballpark in Carlsbad, New Mexico – were removed to make way for a multi-field youth soccer complex.1 It symbolized the way America’s sporting interests had changed and broadened in the roughly three decades since the park was built.

To reduce Montgomery Field to a symbol, though, is to shortchange one American city’s brief but colorful chapter in baseball history.

In nine seasons of pro baseball, Carlsbad and Montgomery Field hosted players and managers who became well-known in the majors. The city and its park played a peripheral role in an unusual managerial experiment. And in 1959, Montgomery Field was the site of a semi-legendary batting feat when a muscular outfielder named Gil Carter drilled a ball into the New Mexico night that might have been the longest home run ever hit – possibly more than 700 feet out of the ballpark and into a neighboring subdivision.

The man who built the ballpark – and the subdivision – was the kind of local big wheel who used to make a pet project out of bringing pro ballclubs to their communities. C.F. “Charlie” Montgomery, a native Arkansan, had played first base on a semipro team but was injured before he could get a professional tryout. Montgomery prospered in Carlsbad as the owner of an insurance agency and as a real estate developer. He belonged to a long list of civic and business clubs and associations. But in his free time, he thought little of driving a few hundred miles to watch a professional baseball game.2

(A little scene-setting: Carlsbad sits in the remote southeast corner of New Mexico, about 75 miles south of the UFO-tourist haven of Roswell, and 170 to 180 miles away from both El Paso and Lubbock, Texas. The city’s biggest claim to fame, Carlsbad Caverns National Park, is slightly to its south. Before the major leagues expanded to Texas, the nearest American and National League teams played in St. Louis, more than 1,000 highway miles away.)

One description of Montgomery, published long after his death, characterizes him as stiff-backed, reserved, and tight with a dollar.3 He may have been all of these things. The record shows, though, that he was unstinting with time and money when it came to baseball. By all accounts, he loved the sport. And his adopted home city must have seemed ripe for a team. According to U.S. Census Bureau data, Carlsbad’s population leaped from 3,708 in 1930 to 17,975 – and still growing – in 1950.

After several years of exploring possibilities, Montgomery found his chance in the summer of 1952. He led a successful campaign to buy the struggling Vernon, Texas, team in the Longhorn League, a Class C loop of eight unaffiliated teams.4 The sale price, not officially disclosed, was believed to fall somewhere between $10,000 and $12,000.5 After the deal closed, the Carlsbad Current-Argus attested that the insurance man “worked long and hard, took personal risks and contributed financial aid in quantity” to the purchase of the team.6 The Carlsbad area is home to major underground deposits of potash, a principal ingredient in fertilizer, and the new ballclub took the colorful name “Potashers” in tribute to the local industry.

Carlsbad lacked a professional-quality ballpark for its newly minted Potashers, but a suitable site was quickly identified. The city held a long-term lease on property owned by the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway, located near a public recreation area on the Pecos River known as the Municipal Beach or simply “the beach.”7 A modest ballpark, commonly known as Santa Fe Park, had been built there in 1940 for use by local teams.8 Crews “completely razed” the grandstand and fences of Santa Fe Park near the end of 1952, while the field was re-seeded, graded and leveled.9 During the Potashers’ existence, Montgomery paid the city the annual cost of leasing the land from the railroad.10

The Potashers’ home consisted of an uncovered concrete grandstand with seating for 3,200, with additional space available for temporary bleachers if needed. Stories written during construction boasted about the park’s lighting system, as well as its “sanitary restrooms with attendants on duty in them all season.”11 Total cost of the facility was given at $45,000.12 The name Montgomery Field appeared in the Carlsbad Current-Argus as early as February 1953, though the park was not formally dedicated in Charlie Montgomery’s honor until early August.13 According to one source, Montgomery’s largesse did not extend to the inclusion of a visitors’ clubhouse, so out-of-town players had to dress at their hotel before games.14

The park’s dimensions escaped specific mention in the local paper but have subsequently been reported as 340 feet down the lines and 390 feet to center.15 (Periodic mentions of home-run distances in the newspaper support these dimensions, give or take a few feet.)16 An aerial photo of Montgomery Field taken in 1959 cuts off part of right field, but appears to show a layout similar to those later used at Jarry Park in Montreal and Colt Stadium in Houston. Rather than arcing or curving, fences leave each foul pole in a straight diagonal line and continue into left- and right-center fields, where a third straight-line fence crosses center field to connect them. In the photo, a scoreboard stands in left field, while a dark “batter’s eye” fence appears to be in place in dead center.17

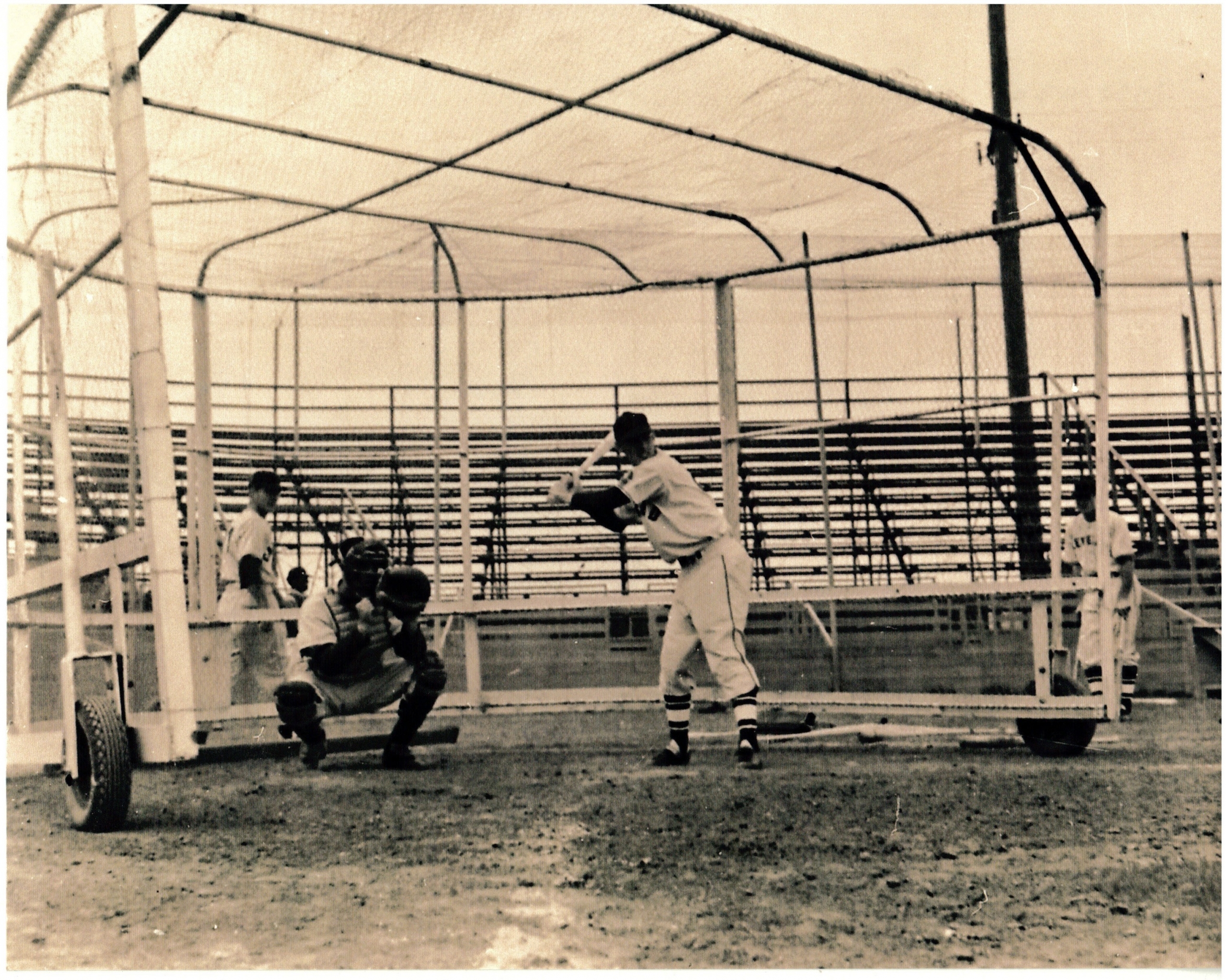

Catcher Ron Smith and infielder/outfielder Jim Ruff in the batting cage at Montgomery Field, April 1957, in Carlsbad, New Mexico.

After a series of exhibitions, Montgomery Field first hosted regular season play on April 21, 1953. New Mexico Governor Edwin Mechem threw a high, wide first pitch on Opening Night. An overflow crowd of more than 3,500 fans watched the home team pull off a tight 3-2 victory over the Artesia (New Mexico) Drillers. Thirty-nine-year-old first baseman Merv Connors, playing his last of 18 pro seasons, hit a fly ball off the left-field scoreboard for the winning run – the first of 34 homers he would hit for Carlsbad in 1953.18 The game marked “a red-letter day for the Cavern City,” the local paper rhapsodized. “The Longhorn League franchise is another long, progressive step forward that marks Carlsbad one of the most live and far-sighted cities in the Southwest.”19

Another New Mexico baseball legend was in the Artesia lineup on Montgomery Field’s first day, though he hadn’t written his name into the record books yet. First baseman Joe Bauman, who went 3-for-3, moved on to Roswell of the Longhorn League in 1954 and hit 72 home runs. He was the first professional player to top 70 home runs in a season.

Under the leadership of former big-leaguer Pat McLaughlin, the Potashers introduced Carlsbad to the pro ranks in fine style. The team’s 80-52 record placed it first in the eight-team Longhorn League, 1½ games ahead of the San Angelo (Texas) Colts. Carlsbad then knocked off Artesia in the semifinal playoff round and the Midland (Texas) Indians in the finals to claim the league title in their first year. Potashers fans quickly adopted a sign of support that was once common in the minor leagues of the Southwest: When a player hit a home run, they would push dollar bills through the protective screen behind home plate.20

Some 83,462 Carlsbad fans turned out to support the team, a league-high average of 1,265 per game. A midseason news story reported that Carlsbad led the Longhorn League and the nearby West Texas-New Mexico League in attendance.21 Season tickets cost $50.40 for 70 games. “You’ll be getting a big entertainment value at a saving, and it’s a certainty that [Organized Baseball] should be the biggest thing to hit Carlsbad since cinema and local option boozing,” a Carlsbad Current-Argus sportswriter opined.22

Clint Rogas, a pitcher with the ’53 Potashers, found a bride in local resident Betty Shelly. The centerpiece at her February 1954 bridal shower was a replica of Montgomery Field, complete with stands, fans, bases, and players.23 The Potashers and their ballpark worked their way into local life in other ways. An Easter sunrise religious service was held at the park in April 1956.24 And a local barbecue restaurant advertised itself as an ideal pregame stop for families in a hurry to get to Montgomery Field. “Try us next time,” the ad declared, “before the game!”25

Although Carlsbad continued to field winning teams, fan support quickly declined. By 1955 attendance had dropped to 46,152, or about 664 per game, and in July the team held a $10,000 fund drive to stay in business. The team raised nearly $1,000 in a six-hour “talkathon” on a local radio station, which included Potasher players and player-manager Thurman Tucker singing songs. Also participating was local radio figure Bill West, who moonlighted as Montgomery Field’s popular, resonant-voiced public-address announcer.26

The Longhorn League folded after the 1955 season, as the 10 strongest teams from two Southwestern circuits – the Longhorn and the West-Texas New Mexico – joined forces in a new Class B league called the Southwestern League.27 This loop lasted only two seasons, as average league-wide attendance dropped from 1,017 per game in 1956 to 321 per game in 1957. The Carlsbad team remained unaffiliated, and none of its players went on to the major leagues, though the team fielded a few players who had already been there. Two of the league’s other teams affiliated with Cincinnati and Washington. This brought a few visiting players through Montgomery Field who later reached the majors, including Jesse Gonder, Sandy Valdespino, and John Wyatt.

The Potashers began the 1957-1958 offseason in limbo. The Southwestern League had run its course, and another attempt to merge the strongest teams of two leagues – this time, the Southwestern and Big State Leagues – fell apart. This left Carlsbad and other cities hustling for a new connection to the pros.28

Charlie Montgomery and other Southwestern baseball leaders, including W.G. Terry of Midland, Texas, developed the idea of a six-team “sophomore league.” The Class D loop would feature players, supplied by big-league teams, with less than two years of experience.29 The local moguls secured agreements with six major-league teams and overcame the concerns of minor-league president George Trautman, who feared an oversaturation of farm teams but granted his approval when a league in Oklahoma folded. In a drawing, the Potashers were matched with the Chicago Cubs.30 In the span of two months, Montgomery and his fellows had gone from uncertain futures to major-league affiliations, with a chance that tomorrow’s stars might pass through Montgomery Field.

The reality was less impressive. The Potashers spent four seasons affiliated with the Cubs, and each year the parent club spread its low-minor-league talent across least four teams.31 Only two Potashers from the team’s first three seasons went on to the major leagues – outfielder Billy Ott for parts of two seasons, and pitcher Jack Warner for parts of four. (Charlie Pagliarulo, who played shortstop and third base for the 1958 Potashers, didn’t make the majors, but his son Mike did.)32

Over those four seasons, Carlsbad teams posted a combined record of 249-254. One game in June 1958 had to be postponed when high winds took down much of Montgomery Field’s left-field fence.33 Their best season came in 1959, with minor-league lifer Walt Dixon in the manager’s seat. Carlsbad went 72-54, good for first place in the league’s Northern Division, nosing out Hobbs by a single game.34 The Potashers came on strong late in the season – one account said they “came through August like a threshing machine”35 – but the Alpine (Texas) Cowboys swept them in a two-out-of-three playoff series for the league title.36 Warner earned the Sophomore League’s Most Valuable Player Award, posting a 13-3 record in 54 games.37

That was also the season when Gil Carter – a strong, strikeout-prone former boxer turned outfielder who had been signed by the legendary Buck O’Neil – briefly put Montgomery Field and Carlsbad on the national baseball map.

On the night of August 11, batting in the last of the ninth inning against pitcher Wayne Schaper of the Odessa (Texas) Dodgers, Carter bombed a belt-high fastball over a 60-foot-high light tower in left field. The ball left the park on the rise, sailing through the darkness and into a nearby subdivision of homes.38 Only 341 fans had bothered to attend that night, according to the box score. With Odessa holding a commanding 6-1 lead, it’s not known how many were still at Montgomery Field to see Carter’s homer.39

A nearby resident called Charlie Montgomery the next day to report finding a baseball near a peach tree in her yard. Fascinated by Carter’s moonshot, Montgomery and Carlsbad Current-Argus sports editor Jerry Dorbin – who had been in the park and witnessed the homer – set out to deduce its length. Using an aerial photograph and maps of the subdivision, the pair concluded that Carter’s homer could have flown anywhere from 650 to 730 feet. The arrangement of bushes and fences in the area made it impossible for the ball to have bounced more than 80 feet, they reported. The Current-Argus ran an aerial photo showing the ball’s remarkable flight. Dorbin spread the word by contributing articles to The Sporting News in 1959 and Sports Illustrated in 1980.40

There is, of course, no objective way to know if Carter’s homer was truly the longest ever hit. And a skeptic would point out that people who measure long-distance home runs are rarely neutral; they are often affiliated with the team doing the hitting and have a vested interest in a good story.41 But those who documented Carter’s homer stood by their measurements. “Don’t call it a ‘myth’ or a ‘claim,’” Dorbin wrote more than 40 years later.42 Schaper said he’d never seen another ball like it, while Carter recalled, “I knew it was something special, I could feel it in my bat when I hit it. I just stood there and watched it.”43

Gil Carter never got to Wrigley Field, and conversely, the Cubs never came to Carlsbad for an exhibition.44 The closest Montgomery Field got to hosting a big-league team came in October 1957, when a barnstorming team of major leaguers played a charity fundraiser game against a team from Roswell. Participants included reigning American League home run and RBI champion Roy Sievers of the Washington Senators, 20-game winner and future Hall of Famer Jim Bunning of the Detroit Tigers, St. Louis Cardinals catcher Hal Smith, and brothers Frank and Milt Bolling.45 Tickets ran $1.75 for box seats, $1.50 for general admission, and $1 for students.46 Another famous baseball traveler, clown Max Patkin, performed at Montgomery Field in July 1959.47

Montgomery Field fans got to watch plenty of visiting talent in Sophomore League action. Future American League Rookie of the Year Don Schwall took a no-hitter into the seventh inning against Carlsbad in May 1959, finishing with a complete-game, three-hit win.48 Outfielder José Cardenal, who played 18 major-league seasons, raked Potashers pitching for three doubles in six at-bats as the El Paso (Texas) Sun Kings won 9-1 in August 1961.49 Other future big-league stalwarts who saw significant action in the Sophomore League included Tony Cloninger and Denis Menke (1958); Coco Laboy, Phil Roof, Chuck Schilling, and future Hall of Famer Willie Stargell (1959); Jesús Alou, Dick Dietz, Jim Fregosi, and Gil Garrido (1960); and César Gutierrez, Dalton Jones, Aurelio Monteagudo, and Gene Michael (1961).

The 1961 Potashers were drawn into the Cubs’ “College of Coaches” experiment, announced in January of that year by Cubs owner Philip K. Wrigley. Wrigley adopted an unusual group-management style involving eight “coaches” who would move between managing and coaching at the big-league level and working in the minor leagues.50

One of those coaches, former infielder Lou Klein, began the season as the Potashers’ manager. On May 3, Klein was promoted after just five games to manage the Triple-A Houston Buffs – taking a job left vacant by Grady Hatton, who became director of player personnel for the expansion Houston Colt .45s.51 On July 13, Klein swapped places with Harry Craft on the major-league Cubs’ coaching staff.52 He capped his eventful season by taking the Cubs’ managerial reins from September 1 through 12, compiling a 5-6 record, before rejoining the team’s coaching staff.53 It was a remarkable rise: Klein began the season managing in a city whose entire population would have fit comfortably into Wrigley Field, and ended it in Chicago.54

Under Klein’s replacement, the returning Dixon, the 1961 Potashers limped to a 56-71 record, fifth in the six-team league, 22 games back. Four of that year’s players eventually reached the majors. Most notable were infielder Jimmy Stewart, who played parts of 10 seasons in the bigs, and pitcher Bill Connors, who followed an undistinguished pitching career with 16 seasons as a major-league pitching coach.55 The Potashers drew just 14,974 fans, or about 236 per game. Other teams in the loop also drew modestly: The Hobbs (New Mexico) Pirates averaged 248 fans per game, the Artesia (New Mexico) Dodgers 154, and the Alpine Cowboys about 150.56

Teams in the relatively larger cities of El Paso and Albuquerque, New Mexico, fared significantly better at the gate. But, shortly after the end of the 1961 season, both cities withdrew to join the Double-A Texas League.57 That effectively spelled the end of the Sophomore League, though it was not confirmed until January 1962.58 Montgomery, the league’s president by that time, blamed its death on low attendance, insufficient financial support from major-league teams, and the decision of an unnamed major-league team to withdraw its affiliation. Montgomery estimated he had lost $100,000 in nine seasons of pro baseball but expressed hope that a team would return.59

Carlsbad’s seemingly tireless baseball backer, however, had finally had enough. In December 1962, he offered the park to the city for $20,000.60 Around the same time, an unnamed Mexican city showed interest in buying and moving the ballpark.61 The city of Carlsbad passed up the chance to buy Montgomery Field, reportedly because the land under the park was owned by the railroad, and state law barred cities from spending public money on parks they could not fully own. Finally, Carlsbad’s American Legion post bought the stadium for $13,000 – a bargain-basement price, given that Montgomery also threw in uniforms, bats, baseballs, and even the Potashers’ old team bus.62

During the years of Legion ownership, Terry Cox – born in Texas and raised in Carlsbad – emerged as a pitching and hitting star for high school and Connie Mack League youth teams. While those teams often played on other fields, Cox is known to have played at least once at Montgomery Field.63 Cox signed with the California Angels as an amateur free agent in 1968. In September 1970 he pitched in three games with the Angels, becoming Carlsbad’s first major leaguer.

Montgomery Field changed hands again in 1968. The Carlsbad American Amateur Baseball Congress, operator of the Connie Mack League youth program, purchased it for $8,000, a sum it laboriously paid off over the course of years.64 By 1970, the facility had been renamed Connie Mack Field or Connie Mack Ball Park.65 In addition to plenty of youth baseball, the former Montgomery Field hosted a variety of events after its minor-league days, including charity donkey softball games and a concert by a regional pop-music band called Don Hudson and the Royal Kings.66

Another tie to Carlsbad’s baseball past disappeared on April 12, 1972, when 74-year-old Charlie Montgomery died at his home in the city.67 Fifteen years earlier, a local sportswriter captured his essence: “Charlie Montgomery giving of his heart and substance for baseball, feeling sick when the Potashers lost and singing all the way home from Hobbs after an especially satisfactory win. His friendship and his support of baseball have already made him a legend in this place where he built a home and career.”68

Charlie Montgomery might have been proud of the 1972 Carlsbad High School baseball team, who brought home a title at his old ballpark the month after his death. Playing in front of 1,532 fans on a 99-degree day, the Carlsbad High Cavemen beat a team from Santa Fe 2-0 to clinch the Class AAAA state high school championship. Ace pitcher Wally Lester threw a two-hit shutout, striking out 15 in a seven-inning game.69 A month later, the Cincinnati Reds chose Lester in the 11th round of the June amateur draft; he played a single professional season at rookie-league level. Other noteworthy ’70s occurrences at the ballpark included a trendy appearance by a small group of streakers in April 1974; what Charlie Montgomery would have thought of that is unrecorded.70

Connie Mack Park faded fast in its last years, in part because the Amateur Baseball Congress had trouble rousing volunteers to help keep it up. A 1980 news story indicated that the lights were far below standard, and the stadium was rumored to be on its way out.71 Another story the following year painted an even starker picture of decay, describing widespread litter, unsafe bleachers, a vandalized concession stand, and the lingering smell of spilled beer: “The place used to hold spectators who watched the pros go at it. Nowadays it more closely resembles a graveyard. It smells like slow death in there.”72 By June 1982, portions of the outfield fence had collapsed, and the light standards had reportedly become too unstable to climb to change the bulbs.73

The Amateur Baseball Congress, which fielded no teams in 1982, said the city had shown interest in taking over the lease on the property but would not commit to keeping it as a baseball park.74 Coverage in the Carlsbad Current-Argus does not capture the specific moment when the lease changed hands, but in March and April 1984, the remnants of Montgomery Field/Connie Mack Park were trucked away to make way for other public sports uses.

The soccer fields didn’t last either. A city development organization eventually purchased the land from the railroad,75 and a mixed-use business development called the Cascades at Carlsbad now occupies the ballpark’s old location off Park Drive. A marker at the Cascades records the approximate site of home plate, honoring Gil Carter and the city’s baseball past.76

Aerial photo of Montgomery Field, the Pecos River, and the surrounding area of Carlsbad, 1964.

Acknowledgments

This story was reviewed by Rory Costello and Jake Bell and checked for accuracy by members of SABR’s fact-checking team.

Sources and photo credit

The author consulted baseball-reference.com and retrosheet.org for background information on players, teams, and seasons. He also relied on historical news stories in addition to those specifically cited, mainly from newspapers in New Mexico.

Photos courtesy of Near Loving’s Bend Photo Archives at www.senmhs.org (Southeastern New Mexico Historical Society).

Notes

1 Mike Genovese, “Soccer for Kicks,” Carlsbad (New Mexico) Current-Argus, April 22, 1984: B6, and accompanying photo and caption; “A Heavy Light Load” (photo and caption), Carlsbad Current-Argus, March 8, 1984: 1; “Transformation Begins” (photo and caption), Carlsbad Current-Argus, April 18, 1984: 3.

2 James B. Barber, “Potashers’ Opener is Dream Come True for Number 1 Fan,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, April 21, 1953: 1; “C.F. Montgomery Dies Here Today,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, April 12, 1972: 1.

3 Toby Smith, Bush League Boys: The Postwar Legends of Baseball in the American Southwest (Albuquerque, New Mexico: University of New Mexico Press, 2014): Chapter Two.

4 “Local Group Trying to Buy Baseball Franchise,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, July 25, 1952: 5.

5 “Ball Club to Select Directors Tomorrow,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, November 5, 1952: 9. According to an online inflation calculator hosted by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, those prices roughly equaled $106,260 to $127,500 in February 2022.

6 “The Little Argus,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, August 26, 1952: 1.

7 Stories that mention Santa Fe Park and the beach area include Ted Oster, “Sideline Stars,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, April 22, 1941: 2; “Circus Comes to Carlsbad,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, September 26, 1944: 5; and “CC to Request Water Survey,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, August 14, 1946: 6.

8 “Sylvines to Play Fort Bliss Baseball Team on New Diamond Today,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, June 20, 1940: 4.

9 “Ball Club to Select Directors Tomorrow.”

10 “City Offered Ball Park for $20,000,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, December 16, 1962: 23.

11 “Potashers Ball Club Seeks Pay for Stock Purchased ‘On Time,’” Carlsbad Current-Argus, January 25, 1953: 13; “Work Begins Tomorrow on Grandstand,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, January 18, 1953: 10.

12 Gil Rusk, “Potashers Open Season Tonight,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, April 21, 1953: 1.

13 Gil Rusk, “On the Cavemen’s Chances and Baseball Season Ducats,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, February 22, 1953: 13; “The Little Argus,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, August 19, 1953: 1.

14 Smith, Bush League Boys. Smith’s book also claims that Montgomery simply took the existing Santa Fe Park and performed the “minimum amount of remodeling” for the Potashers’ use. However, local news stories from late 1952 say the structures of Santa Fe Park were razed to make way for the new Montgomery Field. “Work Begins Tomorrow on Grandstand,” cited above, also makes specific reference to the construction of a new grandstand.

15 StatsCrew.com page on Montgomery Field, accessed March 25, 2022.

16 “The 390-foot center field wall” is mentioned in several stories including Roy Hall, “Potashers Take to Road; Westfield Throttles Dukes,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, May 5, 1960: 16; Hall, “Potashers Still Looking for Victory Over Alpine,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, June 13, 1960: 12; “Stumbling Potashers Try Sun Kings Next,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, July 5, 1961: 12. The latter article refers to a “390-foot elevated wall in center field,” suggesting a taller or higher fence there. A “345-foot left field wall” is mentioned in Roy Hall, “Oxendine, Starr Guide Potashers Past Alpine, 8-3,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, July 3, 1960: 12.

17 The aerial photo in question was taken by Carlsbad Current-Argus sports editor Jerry Dorbin while determining the length of Gil Carter’s home run. It appeared in that paper in August 1959. As of March 2022, the original photo that ran in the newspaper is poorly reproduced in Newspapers.com. A higher-quality version of the photo can be seen accompanying Dorbin, “The Longest Home Run Ever,” Elysian Fields Quarterly: The Baseball Review, 2001, accessed online March 18, 2022.

18 “Potashers Win 3-2 Thriller in Opener,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, April 22, 1953: 7.

19 Rusk, “Potashers Open Season Tonight.”

20 Smith, Bush League Boys. Smith quotes Gil Carter as saying he received $633 in through-the-fence bills following his mammoth home run.

21 “Carlsbad Leads in Attendance in Longhorn, WT-NM Circuits,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, July 12, 1953: 13.

22 Rusk, “On the Cavemen’s Chances and Baseball Season Ducats.” New Mexico gave individual communities the right, or “local option,” to legalize or block alcohol sales. “Local option boozing” presumably refers to Carlsbad’s decision to allow alcohol sales, though the author was unable to determine exactly when this took place.

23 “Wedding Shower Given Recently for Betty Shelly,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, February 24, 1954: 5. Rogas went 2-7 with a 5.71 ERA in 18 games for the Potashers. He pitched in three games for Odessa the following season and left baseball. The Rogases remained married for 61 years until Clint’s death in 2015. Memorial page for Clinton Alvin Rogas Sr., All Faiths Funeral Services, accessed March 25, 2022.

24 “Sunrise Service at Baseball Park Easter Morning,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, March 25, 1956: 1.

25 Advertisement for the Red Chimney restaurant, Carlsbad Current-Argus, June 11, 1954: 8.

26 “Potasher Talkathon Net Nears $900,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, July 25, 1955: 9; John D. Alexander, “Alexander’s Alley,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, July 25, 1955: 9. Roy Hall of the Current-Argus profiled Bill West in “Bill West . . . Suddenly, A Sportscaster,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, January 11, 1968: 16.

27 United Press, “Southwestern League Will Operate with 10 Teams; Artesia Folds Club,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, November 21, 1955: 9.

28 “Potashers to Be in Strong, Newly-Merged League for ’58,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, December 8, 1957: 26; “Potashers Still Trying for Loop,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, January 5, 1958: 18.

29 Associated Press, “New Mexico-Texas Loop May Play,” Alamogordo (New Mexico) Daily News, February 3, 1958: 2; “Sooner Loop WT-NM Key,” Santa Fe New Mexican, February 4, 1958: 8; United Press, “WT-NM Will Play Under the Name Sophomore League,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, February 21, 1958: 7. Terry was chosen as the league’s founding president; Montgomery later replaced him.

30 Associated Press, “League Gets Minors’ OK,” Santa Fe New Mexican, February 14, 1958: 10. The other teams and their major-league affiliations were Midland, Texas: Milwaukee Braves; Plainview, Texas: Kansas City Athletics; San Angelo, Texas: Pittsburgh Pirates; Artesia, New Mexico: San Francisco Giants; and Hobbs, New Mexico: St. Louis Cardinals.

31 According to Baseball-Reference, the Cubs operated five teams beneath Class A in 1958 and 1961, and four teams in 1959 and 1960.

32 Bruce Tillman, “Pagliarulo Joins Andre Chiefs’ Coaching Staff,” InsideMedford.com. Posted July 3, 2016; accessed March 18, 2022.

33 “Rain and Wind Call Carlsbad Out at Home,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, June 29, 1958: 22.

34 Final regular-season standings as printed in the Carlsbad Current-Argus, September 1, 1959: 16.

35 Jerry Dorbin, “Potashers Open Playoffs Tuesday,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, August 31, 1959: 9.

36 Associated Press, “Alpine Wins Title,” Tacoma (Washington) News Tribune, September 11, 1959: D4.

37 United Press International, “Jack Warner Wins Soph MVP Honors,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, September 6, 1959: 18.

38 Jerry Dorbin, “Schaper Hurls Dodgers Past Potashers 6-2,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, August 12, 1959: 12.

39 More than 40 years later, Jerry Dorbin wrote: “A thousand fans were silent for three beats, then Carter circled the bases to gradually rising cheers.” While Dorbin was present for the home run, the listed attendance in the box score does not support this recollection.

40 Jerry Dorbin, “Here’s a Real Tape-Measure Wallop; Homer May Have Traveled 650 Feet,” The Sporting News, August 26, 1959: 41; Dorbin, “The Longest Home Run Ever;” Smith, Bush League Boys.

41 For instance, Mickey Mantle’s famous home run out of Washington’s Griffith Stadium on April 17, 1953 received its 565-foot estimated distance from the Yankees’ press secretary, Red Patterson – a man with an obvious interest in positive, attention-grabbing stories about Yankees players. Nick Anapolis, “Mantle Hits 565-Foot Home Run,” National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum website. No posting date; accessed March 24, 2022.

42 “The Longest Home Run Ever.”

43 Kevin T. Czerwinski, “Carter Blasts Way into Baseball History,” MiLB.com. Posted September 20, 2006; accessed March 18, 2022. Gil Carter died in Topeka, Kansas, in 2015.

44 A Newspapers.com search of the Carlsbad newspaper between 1957 and 1961 turned up no reference to the Cubs visiting their affiliate city. Also, a list of in-season exhibition games between 1921 and 2009, hosted by Retrosheet, does not mention any major-league team ever playing an exhibition in Carlsbad.

45 “Major Leaguers to Play Here,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, October 8, 1957: 6.

46 According to an online inflation calculator hosted by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, those ticket prices equaled $17.54, $15.04, and $10.03 in February 2022.

47 Advertisement for Max Patkin appearance, Carlsbad Current-Argus, July 6, 1959: 7.

48 Jerry Dorbin, “Cowboys Capture Fourth Straight Off Potashers,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, May 20, 1959: 13. Schwall was pitching for the Alpine (Texas) Cowboys.

49 Jerry Dorbin, “Kings Win Series Decider, Brush by Potashers, 9-1,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, August 21, 1961: 8.

50 Rich Puerzer, “The Chicago Cubs’ College of Coaches: A Management Innovation that Failed,” The National Pastime, Vol. 26 (Society for American Baseball Research, 2006.) Accessed online March 17, 2022.

51 “Cubs Boost Klein to Houston Buffs,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, May 3, 1961: 9; Associated Press, “Lou Klein to Manage Buffs,” Bryan (Texas) Eagle, May 3, 1961: 12. Klein left Carlsbad with a managerial record of 2-3.

52 United Press International, “Ex-Potasher Skipper Klein Goes to Cubs,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, July 13, 1961: 11.

53 Puerzer. El Tappe both preceded and succeeded Klein as the Cubs’ manager. Klein served additional stints as Chicago manager in 1962 and 1965, compiling a lifetime big-league won-lost record of 65-82.

54 According to U.S. Census data, Carlsbad’s population in 1960 was 25,541. Wrigley Field’s capacity in 1961 was 36,755, according to the Seamheads.com ballpark database.

55 The other 1961 Potashers to reach the majors were Paul “Jake” Jaeckel and Bob Raudman.

56 The Alpine, Texas, team was a Boston Red Sox affiliate.

57 The El Paso, Texas, team averaged 1,127 fans per game and the Albuquerque, New Mexico, team about 800.

58 United Press International, “Sophomore League Folds Up – Officially,” El Paso (Texas) Herald-Post, January 10, 1962: 16.

59 “Sophomore League Folds Up,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, January 10, 1962: 12. According to an online inflation calculator hosted by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, $100,000 in January 1962 was roughly equivalent to $945,720 in February 2022.

60 “City Offered Ball Park for $20,000.”

61 Roy Hall, “Calling Signals,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, January 9, 1963: 12.

62 Roy Hall, “Legion Votes to Buy Montgomery Field,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, February 19, 1963: 9.

63 On June 28, 1967, Cox pitched for the Rose Gravel team of the Connie Mack League in an exhibition against an independent team from Loving, New Mexico. “Rose Gravel Slams Eagles,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, June 29, 1967: 11. The Carlsbad newspaper did not always mention the locations of Cox’s youth games, so it’s possible that he played at Montgomery Field on other occasions as well.

64 “CML Offering $100 Bill,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, July 2, 1971: 8; “Connie Mack to Buy Park,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, February 28, 1968: 13.

65 “Montoya Will Attend Picnic,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, September 1, 1970: 1.

66 “Show to Feature the Royal Kings,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, July 25, 1963: 3. Current-Argus archives show that charity donkey softball games were held at the park by the Carlsbad Boys’ Club in August 1968 and the Carlsbad Veterans of Foreign Wars in September 1974.

67 “C.F. Montgomery Dies Here Today.”

68 John D. Alexander, “And So, Goodbye,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, July 19, 1957: 9.

69 Roy Hall, “14 Years Later . . . A Caveman State Title,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, May 22, 1972: 8.

70 Roy Hall, “Eventful Night Keeps Cavemen on Top, 13-0, 4-1,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, April 7, 1974: 8. Streaking was a short-lived fad, largely concentrated in 1974, involving nudity in public places.

71 Roy Hall, “Cancel the Funeral,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, July 18, 1980: B2. At the time, Carlsbad High School – formerly a tenant at the park – was building its own on-campus baseball field, adding to the perception that Montgomery Field/Connie Mack Park might be on borrowed time.

72 Mike Cornwell, “The Resurrection,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, March 18, 1981: 8.

73 Roy Hall, “The Death of a Ballpark??,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, June 29, 1982: 10.

74 Roy Hall, “Connie Mack Park Lives,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, July 1, 1982: B1.

75 Umut Newbury, “Groups Want to Build Science Center,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, October 23, 2002: 1A; Larry Henderson, “Working Toward a More Progressive City,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, January 1, 2003: 4A.

76 Update from Carlsbad Mayor Dale Janway, posted on the city’s website August 29, 2020; accessed March 29, 2022.