Tullar Field (Wellsville, NY)

This article was written by Kurt Blumenau

In 1911, Angie Tullar, a prominent resident of Wellsville, New York, gave her community the use of a parcel of land for public recreation. Over time, this generous donation provided the residents of her small village with a front-row seat to watch baseball players ranging from Ty Cobb to Tony Conigliaro.

Tullar Field, a ballpark built on the donated land, hosted Class D minor-league play in the Interstate League from 1914 through 1916, and again in the Pennsylvania-Ontario-New York (PONY) League and New York-Pennsylvania League almost continuously between 1942 and 1965.1 Five big-league teams affiliated with Wellsville over the years, and four played exhibitions there.2

The grandstand and dugouts from Tullar Field’s professional period were torn down soon after the minor leagues left town, and a subsequent highway project lopped a corner off the property. As of 2025, though, a softball and baseball field still stood where the pros once played, continuing the site’s long history of public recreation.

The story of Tullar Field began in the early 20th century when Wellsville, formerly a center for lumbering, was enjoying an economic boom driven by oil production.3 The village in Allegany County, eight miles north of the Pennsylvania border, had seen its population rise from 2,049 in 1880 to 4,382 in 1910.4

Before his death in 1896, Angie Tullar’s husband, Eugene, had reportedly invested in oil; he’d also operated a successful hardware store for many years.5 Eugene left his widow in a position to be philanthropic. She funded the addition of a maternity annex to Wellsville’s Jones Memorial Hospital, as well as college scholarships for local students.6

The Tullars’ son, Bayard, was a Cornell University-educated lawyer.7 He was also a baseball enthusiast who had pitched, managed, and umpired at the local level.8 By some tellings, Bayard convinced his mother to donate a proper athletic field. In other versions of the story, Angie took it upon herself to arrange for a field after observing her son’s baseball activities.9

Either way, sources agree that the donation was made in 1911, with the name “Tullar Field” appearing in newspaper stories as early as June 2 of that year.10 During its decades in professional baseball, the property was not formally owned by the village of Wellsville. Rather, it was managed on the community’s behalf by a commission whose members over the decades included Bayard Tullar and his son, also named Bayard.11

Angie Tullar’s chosen site on South Main Street proved to have one significant drawback. The property is located on a bend in Dyke Creek, a brook that joins the Genesee River a short distance away. Prolonged heavy rainfall put Tullar Field under water in June 1919, February 1939, May 1945, May 1946, June 1947, and October 1955, and came close in March 1964. After pro baseball departed, the park and surrounding areas were also flooded by the devastating Hurricane Agnes in June 1972.12

The park worked fine in most weather conditions, though, and it quickly gained momentum as a baseball destination. The commission in charge of the field began booking traveling teams, including Black teams, as early as 1912. A grandstand was in place the same year, although it was replaced in 1916 with a structure with seating for more than 1,000.13

Just three years after the creation of Tullar Field, Wellsville landed in a professional league. The Interstate League, like the later PONY and New York-Penn circuits, was made up of communities in New York and Pennsylvania.14 A planned team in Niagara Falls was deemed too far away from the other five communities. That franchise was offered to Wellsville instead, which joined the league less than a month before play began.15

Advertisement for the first Interstate League game at Tullar Field, Allegany County (Wellsville, New York) Reporter, May 19, 1914: 7.

The first professional game at Tullar Field took place on a wet and overcast May 22, 1914. Wellsville made it a memorable one, beating Hornell, 7–5, in front of about 1,200 fans. The Wellsville Daily Reporter called the game “a great success” despite poor weather, noting that both teams had been so recently organized that neither had had time to play preseason practice games.16 The Wellsville team finished fifth in the six-team league with a 41–60 record. Manager Elmer Bliss, who had played two games with the American League’s New York Highlanders in 1903 and 1904, was the only team member to appear in the majors.

Wellsville claimed the 1915 playoff championship in a dispute with Olean, then slipped back to fourth place in 1916, a season in which the Interstate League began with eight teams and ended with five.17 Catcher Ray Kennedy, a 1916 pickup from Erie, was drafted by the St. Louis Browns late that season and went straight from Tullar Field to the majors.18 The Interstate League planned a four-team season in 1917, with Wellsville included. But the collapse of the Bradford, Pennsylvania, team put an end to the league and Tullar Field’s first stint as a professional ballpark.19

As proof that Tullar Field had put the village on the baseball map, Wellsville fans got to enjoy three visits by big-league teams in this period. On July 5, 1916, Hughie Jennings’ Detroit Tigers beat the Wellsville team, 9–4. Cobb, the nine-time defending AL batting champion, pitched the final four innings, surrendering all of Wellsville’s runs.20

The St. Louis Browns followed the Tigers to Tullar on August 14, 1916, winning 4–1 before a crowd of 2,000. Spike wound injuries from a previous game kept future Hall of Famer George Sisler out of the Browns’ lineup. Browns manager Fielder Jones had played in the region as a young man; his hometown of Shinglehouse, Pennsylvania, is about 20 miles from Wellsville.21

For excitement, neither game approached the events of June 18, 1917, when John McGraw brought his New York Giants to town. McGraw had found his first professional success as a member of a Wellsville team in 1890, and the village pulled out all the stops to greet him, including a large parade and “a delegation of the prettiest young ladies in the city” to accompany the Giants’ players and traveling party.22 A crowd reported at more than 4,000 people filled the ballpark past capacity to watch the Giants beat a picked team of locals, 13–3.23

After that, Tullar Field settled into a quarter-century without pro baseball—but not without activity. The ballpark was used for amateur baseball and football games, including by St. Bonaventure University’s football team.24 One amateur game in 1937 reportedly drew 3,000 fans, a sizable crowd by the standards of the ballpark.25 Other activities included high school track meets, boxing matches to entertain the unemployed during the Great Depression, a Boy Scout jamboree, and an ice-skating rink erected in cold weather.26

The village’s opportunities to use Tullar Field expanded further in August 1936, when permanent lights were installed at a cost of $7,000.27 Events held under the lights included a regional political rally in September 1940 in support of Republican presidential candidate Wendell Willkie. Willkie wasn’t there; US Congressman Bruce Barton of New York was the featured speaker, addressing a crowd estimated at 4,000 to 7,000 people.28

Local newspaper ads in August 1937 promoted a game that was to have been played at Tullar Field on August 10 between Black teams from Detroit and Indianapolis.29 Retrosheet’s records cast some doubt on the promotion: They show that the Indianapolis Indians of the Negro American League played in Dayton, Ohio, that night. In any event, two rounds of torrential rain that afternoon caused significant property damage in Wellsville, flooding streets and basements and interrupting municipal water supply for some residents.30 Available sources give no proof of any game involving Black teams in Wellsville that night.31

More intriguing is an announced matchup of the Negro National League’s Homestead Grays and Newark Eagles at Tullar Field four years later almost to the day, on August 13, 1941. Pregame advertising listed players including Monte Irvin, Buck Leonard, Vic Harris, and Leon Day.32 The night’s weather in nearby communities was described as uncomfortably cold and windy, but not wet; a ballgame in Olean, about 35 miles west, was played on schedule.33 But once again, available newspapers—including those in the ProQuest database of Black publications—made no reference to either a game result or a cancellation.34 Absent firm proof that the game was played, one must assume that it wasn’t.

Other attractions were in store for Wellsville baseball fans in 1942. The World Series champion New York Yankees, looking to replace a Class D team in a defunct league in Maryland, scouted Batavia and Wellsville as possible replacements.35 Wellsville won out, and PONY League officials voted to admit the village on February 26.36 Improvements made to Tullar Field included locker room upgrades and a new fence.37

After a 26-year wait, pro baseball returned to Tullar Field on April 30, 1942, in front of 2,500 fans. Hornell spoiled the big day by beating the home team, 8–4.38 They weren’t in the Opening Day lineup, but future Yankees Jerry Coleman and Charlie Silvera called Tullar Field home that season en route to collecting a combined 12 World Series championships. Wellsville finished the season tied for fourth place with a 65–60 record, drawing 29,565 fans and turning a small profit.39 (Tullar Field’s single-season attendance record was set in 1947, when a Boston Red Sox farm team drew 54,442 fans.)40

While information is sparse on Tullar Field’s dimensions during its first pro stint, a news story from just before the 1942 season gives a hint of the park’s size at that time. The story mentions batting-practice home runs being hit 330 feet to right field, 353 to center field, and 338 to left—implying, though not stating, that those were the marked distances.41 Four aerial photos of the park taken between 1952 and 1963 show a field layout not tremendously longer to straightaway center than down the lines, but with a deeper bulge in right-center field.42 A story in 1961 cited the center-field distance as 354 feet.43 The exterior of the park was ringed by tall elm trees.44

The snug confines of what one newspaper called “tight little Tullar Field” made a no-hitter a challenge, but several pitchers managed it during the PONY and New York-Penn era.45 They were:

- Ken Fremming of Jamestown on August 27, 1947;

- Lou Blackmore of Wellsville against Lockport on August 31, 1948, in an 11-inning, 7–3 loss that included 17 walks and a delay for a skunk on the field;

- Dick Sherrow of Wellsville against Geneva on September 2, 1960; and

- Ernie Abels of Wellsville against Jamestown on June 6, 1965.46

Also worth mentioning here is Sonny Gilman of Wellsville High School, who struck out 14 of the 16 batters he faced in a cold-shortened, five-inning no-no against Alfred-Almond High in April 1956.47

Tullar Field’s seating capacity, between grandstand and bleachers, was variously listed as 2,000 to 2,500.48 A crowd of 2,622 on Merchants Night on June 27, 1956, was hailed at the time as a new record for the ballpark—perhaps by people who hadn’t been in the crush to see John McGraw and the Giants in 1917.49

To return to the Yankee era, the parent club drew 2,135 to Tullar Field on June 29, 1943, for the last known big-league exhibition in Wellsville. Yankees starter Tommy Byrne threw a complete-game five-hitter, while the big-leaguers abused their farmhands for 24 hits in a 19–2 laugher.50 Perhaps the next most memorable moment from the Yankee affiliation took place on August 9, 1944, when Wellsville Mayor Thomas Martin and members of the Yankees had to protect umpire Leo Fournier from a raging mob after a disputed third-strike call in a close loss.51

The Yankees held their Wellsville affiliation until 1946. They were succeeded by:

- The Boston Red Sox (1947-48);

- Unaffiliated teams (1949, 1951);

- The Washington Senators (1950);

- The St. Louis Browns (1952);

- The Milwaukee Braves (1953-1961); and

- The Red Sox again (1963-65).

Wellsville did not field a professional team in 1962.

Fan favorites in the first decade of PONY League ball at Tullar Field included Cuban outfielder Angel Scull—once described as “the most popular player ever to wear Wellsville flannels”52—and Jim Greengrass, a Central New Yorker who joined the team at age 16 in 1944, hit .349 the following season, and eventually played five seasons of big-league ball.53 Pitcher Dick Littlefield went 13–4 with a 1.97 ERA in 1947 en route to the majors, where he pitched against Greengrass.54

Baseball at Tullar Field peaked under the Braves, when managers included former Philadelphia Phillies infielder and future big-league coach Alex Monchak and players included future major-leaguers Phil Niekro,55 Bill Robinson, Elrod Hendricks, Don Nottebart, Vern Handrahan, and Merritt Ranew. The Braves won four straight regular-season championships from 1956 to 1959, also winning the postseason playoffs in 1956 and ‘59.

Some of their finest performances came from players who made the majors briefly or not at all, including:

- Third baseman Ted Sepkowski (.339/37/145 in 1953; .377/45/144 in ‘54)56;

- Third baseman Dick Selinger (league-leading 100 RBIs in 1957);

- Pitcher Luis DeLeon57 (17–5, 2.36, with 19 complete games in 20 starts in 1957);

- First baseman Corky Withrow (league-leading 32 HRs and 142 RBIs in 1958);

- Pitcher Ed Banach (13–1, 1.92 in 1958);

- Outfielder Marcial Allen (.356 and tied for the league lead with 92 RBIs, 1959); and

- Pitcher Bennie Griggs (a league-leading 21 wins and 21 complete games in 1959).

The Braves era also generated a heartwarming story in 1956, when fans took up a collection to support outfielder Joe Edgley and his wife, Lil, who had just given birth to a boy. The total donation of $135 paid the family’s hospital bill.58

The success of the Braves and their individual stars didn’t make the turnstiles spin at Tullar Field, though. Attendance reached 45,799 in 1955 and then kept dropping—to 30,470 in 1956, 24,970 in 1958, 21,806 in 1960, and 17,385 in 1961, for a decline of 62 percent over just seven seasons.59

Wellsville’s challenges mirrored those in towns across America as television, air conditioning, and other things offered new leisure-time options. In 1949, 448 minor-league teams operated across 59 leagues; by 1963 the minors had shrunk to 129 teams across 18 leagues.60 Wellsville faced additional pressure as one of the smallest communities in the minors, with fewer than 6,000 village residents in 1960.61 It was a sign of the times when Wellsville Braves officials asked the local Board of Education for financial help in May 1960, reasoning that—since the school district used Tullar Field for football and baseball games—it should chip in for maintenance.62

“KEEP AN INDUSTRY IN WELLSVILLE / Support the Wellsville Braves,” newspaper ads challenged in 1961.63 The call to action didn’t work, as the Braves left at year’s end. The Wellsville Daily Reporter described the Braves’ last home game, an 11–8 loss to Olean on August 31, as “probably the last [New York-Penn] game in Wellsville history.”64 In another example of the season’s frustrations, the traveling Kansas City Monarchs, with legendary Satchel Paige, were booked to play the Detroit Stars at Tullar on August 16. But Paige was a no-show, reportedly because of an ailing child, and the game was described as “a hoax” and “a farce” that ended after seven innings when both teams walked off the field.65

Tullar Field, without pro baseball in 1962, suffered from vandalism and decay.66 The biggest event of the year was a re-election rally in late October for New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller, who had the misfortune to speak at night in snowy 29-degree weather. Some 900 people came to Tullar Field anyway.67 Religious films produced by the Rev. Billy Graham also became an annual fixture at Tullar Field for several years, with 800 people attending showings in July and August 1962.68

The Red Sox gave Tullar Field a three-season reprieve in December 1962, relocating their New York-Penn affiliate from Olean.69 The ballpark received upgrades before the 1963 season that included an expanded home clubhouse, repairs to a vandalized entrance, new paint, and new screening in front of the first-base bleachers.70 One thing missing was beer, because no alcohol could be sold at Tullar Field.71

Wellsville’s new team fared well in 1963, finishing in second place with a 73–57 record, before slipping to third place (70–60) in 1964 and fourth (62–64) in 1965.72 Three future big-leaguers set off offensive fireworks in 1963. Conigliaro hit .363 with 24 homers and 74 RBIs, earning Rookie of the Year honors;73 George Scott went .293/15/74; and Joe Foy hit .350 in limited duty. The next season, Carmen Fanzone hit .386 in 82 games, while Bill Schlesinger—who had a single at-bat in the majors the following year—lit up New York-Penn pitching to the tune of .341, 37 homers, and 117 RBIs.

Reveling in their home bandbox, the Red Sox set a league record of 153 homers in 1963, then blasted past it with 192 in 1964.74 Visiting teams enjoyed it too, as Tullar Field played host to a rash of offensive outbursts in its final seasons:

- During the Braves’ last year, the Braves and Geneva Redlegs combined for eight homers on June 4, 1961. Geneva won, 16–7.75

- On May 14, 1963, the Wellsville Red Sox and Erie Sailors hit 10 total homers in a 13–11 Wellsville win.76

- The Red Sox and Binghamton Triplets went deep a combined nine times on May 27, 1964, in a 16–11 Triplets victory. “A strong breeze blowing out to center” was credited for the outburst.77

- The Red Sox and Geneva Senators combined for seven homers, including two grand slams and four homers by Wellsville in the same inning (the bottom of the second) in a 24–15 Wellsville win on May 20, 1965.78

- The Red Sox and Triplets clouted eight homers on July 26, 1965—three by Wellsville’s Jerry Dorsch—as Binghamton came out on top, 17–16.79

Pitchers occasionally evened the ledger in dramatic fashion, perhaps because batters were busy swinging from the heels. In Tullar Field’s final two seasons, a pair of pitchers each struck out 20 batters in a game there. Jamestown’s Jack Nutter accomplished the feat in a 7–3 win on May 15, 1964, and Wellsville’s Cecil Robinson struck out 20 Auburn Mets on June 4, 1965, but lost a 3–2 heartbreaker on a late home run.80 Wellsville and Batavia batters also set a new New York-Penn record with 35 strikeouts in a 13-inning game on August 9, 1964.81

This anything-can-happen style of baseball didn’t draw fans, though. The Red Sox’ season attendance never came close to past levels, topping 20,000 only once in three seasons. It peaked at 20,183 in 1964, when the team reportedly finished with a small profit, then sputtered to a league-low 16,377 in 1965.82

Problems with the ballpark’s structure also emerged. In July 1963, a state inspector told Tullar Field’s commissioners that the grandstand needed repair and modification, including wider aisles. These changes would not only require significant investment, but would reduce the park’s seating capacity by up to one-third.83 The following month, Tullar Field’s failing septic facilities were blamed for a powerful stench, leading to a suggestion that the restrooms be closed.84 Some of Tullar Field’s aisles and stairs were widened in the lead-up to the 1965 season; news coverage is silent on the resolution of the park’s septic problems.85

The end for pro baseball at Tullar Field came in a one-two punch at the end of August 1965. On August 29, Red Sox officials announced plans to transfer their New York-Penn team to Oneonta, New York, the following season. Ed Kenney, Boston’s assistant farm director, said Wellsville was “just too small a town, and the potential drawing power of a team is limited. We here feel that it would just be a continual struggle each year to keep an operation going there.”86

The final pro game at Tullar Field took place the following night. An eighth-inning sacrifice fly by Wellsville second baseman Tom Moorman brought home left fielder Jim Beamer with the deciding run in a 4–3 Red Sox victory over the visiting Batavia Pirates. Future Pittsburgh Pirates All-Star Manny Sanguillén, a 21-year-old rookie, appeared as an unsuccessful pinch-hitter for Batavia. News reports did not specify how many fans turned out.87 Scheduled games on August 31 and September 1, the latter a doubleheader, were washed out by rain and not rescheduled.88

The year 1966 passed with more decay and vandalism, the theft of public-address gear from the press box, and a condemnation order for the grandstand. In late December officials announced that the commission in charge of Tullar Field would turn over its title to the village. Officials planned to combine Tullar Field with adjacent property and build new fire, police, and recreational facilities.89

In what must have been a bittersweet moment, Bayard C. Tullar—son of Bayard the ballplaying attorney, grandson of Angie, and last president of the Tullar Field Association—was pictured on the front page of the Wellsville newspaper on January 6, 1967, standing on the park’s infield as he handed the deed to Tullar Field to Mayor Robert Gardner.90 The village didn’t dawdle: By the end of that month, the decrepit grandstand and dugouts had been razed.91

The police and fire stations were built in 1970-71 and a long-planned four-lane highway—New York State Route 417—sliced off one of the property’s edges in 1977.92 But the core field area was not built on, and despite poor conditions, Tullar Field remained in use for amateur sports events, with lights and portable grandstands in place.93

As part of celebrations of America’s bicentennial, the park hosted an ecumenical religious service on July 4, 1976.94 In the mid-’70s the village also offered Tullar Field as a site for Halloween shaving-cream fights, with doughnuts and hot chocolate provided by police and a local supermarket. The youth of Wellsville had taken to using shaving cream for Halloween pranks, and officials hoped to contain the horseplay to one location.95

Tullar Field got a new lease on life in 1979, when a local bank, First Trust National Bank, funded a thorough $10,000 renovation for softball use. The younger Bayard Tullar, again following in his father’s footsteps, was a member of the bank’s Board of Directors. The project included the installation of permanent seating and dugouts. “It belongs to all of us,” Deputy Mayor Donald Ludden said. “Let’s use it together.”96

As of 2024, the field still had a softball-style all-dirt infield, though a roundup of local sports facilities described it as a “full-size baseball field” with concessions, bleachers, trash bins, parking and restrooms.97 Pro baseball is gone, but legends are still being created there. In June 2024, the Lady Lions softball team of Wellsville High School celebrated the placement of a plaque at Tullar Field commemorating their recently won state championship.98

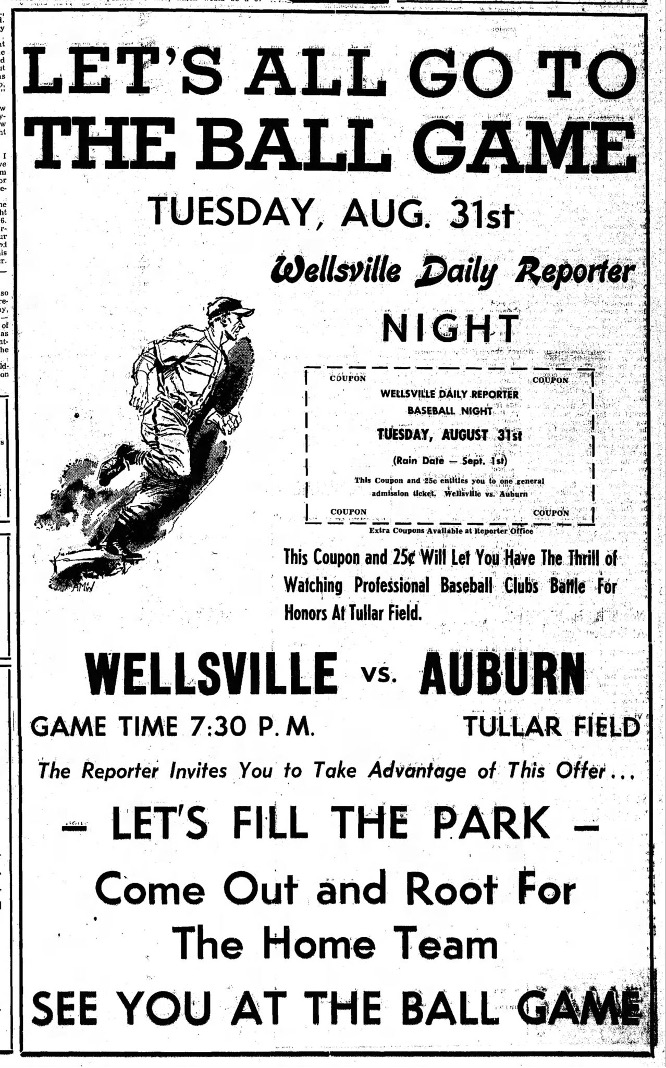

Advertisement for what would have been one of the last professional games at Tullar Field, scheduled for August 31, 1965. The game was rained out, rescheduled for September 1, rained out again, and never played; the park hosted its final game on August 30. From the Wellsville Daily Reporter, August 27, 1965: 3.

Acknowledgments

This story was reviewed by Rory Costello and Abigail Miskowiec and fact-checked by members of the SABR BioProject factchecking team.

Sources and photo credit

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author used the Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org websites for general player, team and season data, as well as numerous news stories on Newspapers.com, FultonHistory.com, and NYSHistoricNewspapers.org.

Undated aerial photo of Tullar Field used by permission of the Allegany County (New York) Historical Society (http://alleganyhistory.org).

Notes

1 Wellsville did not host a New York-Penn League team in 1962. Also, Wellsville’s teams operated at Class D from 1942 to 1961, then moved to Class A from 1963 to 1965 following a structural reorganization of the minor leagues.

2 In December 2020, Major League Baseball announced that seven Black baseball leagues that operated between 1920 and 1948 would be considered major leagues. The Negro American League between 1937 and 1948 and the Negro National League of 1933 through 1948 were among the seven leagues. “MLB Officially Designates the Negro Leagues as ‘Major League,’” MLB.com, posted December 16, 2020, https://www.mlb.com/press-release/press-release-mlb-officially-designates-the-negro-leagues-as-major-league.

3 “History,” Village of Wellsville website, accessed December 2024, https://www.wellsvilleny.com/history.html; John Loyd, “Wellsville Part 1: The Heart of Allegheny County,” Olean Times Herald, June 9, 2009, https://www.oleantimesherald.com/news/wellsville-part-1-the-heart-of-allegany-county/article_1dfbdce5-e7b5-5411-b28a-a6a55a23de86.html.

4 1880 US Census, Volume 1, 264, https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1880/vol-01-population/1880_v1-11.pdf; 1910 US Census, Volume 1, 93, https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1910/volume-1/volume-1-p3.pdf. As a side note, two independently governed communities in Allegany County, New York, share the name Wellsville: the village where Tullar Field is located and the larger town that surrounds it. The population figures given in this paragraph are for the village.

5 Clyde P. Allan, “Horse and Buggy Wellsville Was Proud and Prejudiced,” Wellsville (New York) Daily Reporter, June 29, 1957: 5B; “Angie Tullar Is In Her 90th Year,” Whitesville (New York) News, March 27, 1930: 1. Angie Tullar’s husband was identified as E.B. Tullar in advertisements for his store, but online sources confirm that his first name was Eugene, including 1880 U.S. Census records accessed through Familysearch.org in December 2024, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MZZM-HPR.

6 Ruth Brown, “Roaring 20s Saw Hospital Converted from Residence,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, January 7, 1966: 4; “Angie Tullar Is In Her 90th Year.”

7 “Vicinity News,” Buffalo Enquirer, July 19, 1898: 2; “Personals,” Allegany County (Wellsville, New York) Reporter, December 27, 1895: 8, https://nyshistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=talr18951227-01.1.8&srpos=1&e=——-en-20–1–txt-txIN———-.

8 “‘This Is Great Age,’ Says Woman, 91,” Buffalo Evening News, March 24, 1931: 1; “Base Ball for Wellsville,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, July 30, 1907: 8, https://nyshistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=wdr19070730-01.1.8&srpos=1&e=——-en-20–1–txt-txIN———-; “Wellsville Won,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, August 27, 1903: 8, https://nyshistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=wdr19030827-01.1.8&srpos=2&e=——-en-20–1–txt-txIN———-.

9 Allan, “Horse and Buggy Wellsville Was Proud and Prejudiced”; “‘This Is Great Age,’ Says Woman, 91.” Both articles were written well after Angie Tullar made her gift. The latter may be more trustworthy, as it directly quotes Bayard Tullar as saying, “Mother believed we needed a field – and she arranged to get one. That’s all there is to it.”

10 “Turbine Boys Win,” Allegany County Reporter, June 2, 1911: 3, https://nyshistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=talr19110602-01.1.3&srpos=1&e=——-en-20–1–txt-txIN———-.

11 “Wellsville Opens Its Drive for Tullar Field Lighting,” Buffalo News, April 9, 1936: 23; “Surrenders Deed” (photo and caption), Wellsville Daily Reporter, January 6, 1967: 1.

12 This list might not be exhaustive. “Wellsville Interested in Amateur Baseball,” Buffalo News, June 17, 1919: 20; “Brief Summary of Events,” Potter (Coudersport, Pennsylvania) Enterprise, February 23, 1939: 2; Associated Press, “Rainfall Floods Hornell Sections,” Ithaca (New York) Journal, May 18, 1945: 1; “Bradford-Olean Flood Damage Mounts,” Buffalo News, May 28, 1946: 1; “Streams Recede After Flooding Part of Bradford, Low WNY Areas,” Buffalo News, June 3, 1947: 1; “Rains Flood WNY Roads, Ruin Bridges,” Buffalo News, October 15, 1955: 1; “Action Is Demanded for Vital Changes in Flood Controls,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, March 10, 1964: 1; “Wet Grounds” (photo and caption), Wellsville Daily Reporter, June 22, 1972: 1.

13 “Baseball Prospects Good at Wellsville,” Buffalo News, April 29, 1912: 13; “Field Day Program,” Wellsville Reporter, May 28, 1912: 5, https://nyshistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=wdr19120528-01.1.5&srpos=1&e=; “A New Grand Stand for Tullar Field,” Wellsville Reporter, February 22, 1916: 3, https://nyshistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=wdr19160222-01.1.3&srpos=7&e=——-en-20–1–txt-txIN———-.

14 In addition to Wellsville, Interstate League communities that later fielded teams in the PONY or New York-Penn Leagues were Bradford and Erie, Pennsylvania, and Hornell, Jamestown, and Olean, New York.

15 “Wellsville Fans Are Working for League Base Ball,” Olean (New York) Evening Herald, April 28, 1914: 6; “Base Ball This Summer,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, April 28, 1914: 6, https://nyshistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=wdr19140428-01.1.6&srpos=2&e=——-en-20–1–txt-txIN———-.

16 “Wellsville Wins,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, May 23, 1914: 8.

17 “Blames President and Directors for State of Affairs,” Olean Evening Herald, September 13, 1915: 6; “Lohrrmen Hold A Little Pennant Raising Bee Today,” Olean Evening Herald, September 14, 1915: 6; “Sport Film Flickers,” Elmira Star-Gazette, September 7, 1916: 8.

18 “Interstate League Player is Drafted,” Elmira Star-Gazette, September 12, 1916: 13. Kennedy appeared in one major-league game, grounding out as a pinch-hitter against the Detroit Tigers on September 8, 1916.

19 “Interstate Forms Four-Club Circuit,” Binghamton Press, May 2, 1917: 14; “Conroy Is Here Greets Friends,” Elmira Star-Gazette, May 21, 1917: 8.

20 “Cobb Pitches in Exhibition Won by Tiges [sic],” Detroit Free Press, July 6, 1916: 15. In his 24-season major-league career, Cobb made three pitching appearances – two in 1918 and one in 1925.

21 J.B. Sheridan, “Browns Take Game from Wellsville, 4-1, on Way East,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, August 15, 1916: 6; W.J. O’Connor, “Sisler, Barely Able to Walk on Injured Foot, May Not Be Used Against Athletics,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 15, 1916: 12.

22 “Proclaim Holiday for Manager John McGraw,” Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Telegraph, June 18, 1917: 10.

23 Some sources give different scores for the game; this account sides with the one printed in “New York Giants vs. Wellsville,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, June 19, 1917: 6, https://nyshistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=wdr19170619-01.1.6&srpos=2&e=. By this account, the crowd packed all available bleacher and grandstand seats, occupied 600 temporary chairs along the foul lines, sat in 100 parked cars with a view of the field, or simply stood where they could.

24 “St. Bona’s vs. Alfred, Thursday, November 19,” Olean Evening Herald, November 13, 1914: 4. The school was known as St. Bonaventure’s College until 1950.

25 “Bunched Hits in Two Frames Give Sinclairs Win over Nationals,” Olean Times-Herald, July 30, 1937: 15.

26 “Friendship Wins Triangle Meet,” Buffalo News, June 17, 1924: 28; “V.F.W. Post Plans Outdoor Boxing Card,” Rochester (New York) Democrat and Chronicle, August 14, 1932: 5A; “Allegany District Scouts to Gather,” Buffalo Evening News, May 24, 1929: 29; “Village to Seek Coasting Place,” Buffalo Evening News, December 11, 1936: 29.

27 “Wellsville to Dedicate Floodlights,” Olean Times-Herald, August 5, 1936: 27.

28 “Barton Says U.S. Opposes 3d Term,” Buffalo Evening News, September 4, 1940: 21; “Americans Want No Third Term, Claims Bruce Barton,” Olean Times-Herald, September 4, 1940: 7. Willkie was resoundingly defeated by Franklin D. Roosevelt in that November’s election.

29 “Wellsville Is In Lime Light,” Potter Enterprise, August 5, 1937: 1; advertisement for game, Friendship (New York) Register, August 5, 1937: 4. The teams were described in pregame publicity items as “the Indianapolis A.B.C. and Detroit Stars of the Negro American League.”

30 “Rains Flood Wellsville, Gardens Hit,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, August 11, 1937: 8; “Floods Menace Towns in W.N.Y. After Rainstorm,” Buffalo Evening News, August 11, 1937: 1.

31 Research using the Newspapers.com, ProQuest, FultonHistory and NYSHistoricNewspapers databases in December 2024 did not find specific reference to the game being either played or canceled. Retrosheet maintains a list of Negro League games by location, and as of December 2024, they had no record of any games being played at Tullar Field or anywhere else in Wellsville. https://www.retrosheet.org/NegroLeagues/ballparks.html.

32 “Negro Stars to Play at Wellsville,” Olean Times-Herald, August 11, 1941: 9.

33 “Smrekar Hurls Jamestown to Win Over Pitlermen on Appreciation Night Game,” Olean Times-Herald, August 14, 1941: 10.

34 Research was conducted in December 2024 using the Newspapers.com, ProQuest, FultonHistory, and NYSHistoricNewspapers databases. Retrosheet records as of June 2025 indicated that the two teams played each other in Altoona, Pennsylvania, on August 12, but had no record of either team playing anywhere on August 13.

35 “Triplets Lease Park, Seek Pony League Farm,” Binghamton Press, February 18, 1942: 19.

36 “Eight-Team Pony League to Open Season April 29,” Olean Times Herald, February 27, 1942: 8.

37 Jack V. Moore, “Wellsville Welcomes Return of Pro Ball,” Olean Evening Herald, April 30, 1942: 8.

38 “Hornell Takes 8-4 Decision from Wellsville,” Bradford (Pennsylvania) Evening Star and Daily Record, May 1, 1942: 10.

39 “Pony League,” Elmira Star-Gazette, September 8, 1942: 10; “Yanks Plan on ‘43 Pony Ball, U.S. Agreeable,” Olean Times-Herald, October 6, 1942: 6.

40 “Flag Not Attendance Magnet,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, December 13, 1962: 7.

41 Jack V. Moore, “Wellsville Welcomes Return of Pro Ball,” Olean Evening Herald, April 30, 1942: 8.

42 Photos from 1952, 1955, 1958, and 1963 were accessed via HistoricAerials.com in December 2024. Also as of December 2024, the Stats Crew website—without providing a source or date—gave the field’s dimensions as 335 feet to left, 357 to center, and 300 to right. “Tullar Field,” Statscrew.com, https://www.statscrew.com/venues/v-2886.

43 Frank Cady, “Braves Lose Opener to Olean,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, May 1, 1961: 7.

44 “Booster Club Officials Call Meeting Monday,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, October 28, 1955: 7.

45 “Triplet Hosts Willing, Abels,” Binghamton Press, June 10, 1965: 25.

46 Associated Press, “Ken Fremming, Jamestown, Has No-Hit Game,” Bradford (Pennsylvania) Era, August 28, 1947: 14; “Skunk Temporarily Halts Wellsville-Lockport Game,” Buffalo News, September 1, 1948: 49; “Blackmore Hurls 11-Inning No-Hitter in P.L., Loses, 7-3,” Buffalo Evening News, September 1, 1948: 50; Associated Press, “Sherrow Hurls No-Hit Shutout in NYP League,” Syracuse (New York) Post-Standard, September 3, 1960: 12; Chuck Ward, “Abels Spins Sox No-Hitter Against Jimtown in 3-0 Tilt,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, June 7, 1965: 8. This list is based on an all-time no-hitter log included in the 2019 New York-Penn League media guide.

47 “Sonny Gilman Hurls Near-Perfect First Game,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, April 25, 1956: 7. As of December 2024, Baseball-Reference had no information to suggest that Sonny Gilman pitched professionally.

48 “County, Town & Village,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, June 30, 1960: 6; “Tullar Field,” StatsCrew.website.

49 “Record Crowd Sees Braves Beat Hornell, 9-5,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, June 28, 1956: 4. Merchants Night is a promotion in which local businesses buy blocks of tickets and distribute them for free to customers.

50 “Yankees Crush Wellsville, 19-2,” Elmira Star-Gazette, June 30, 1943: 11; “Batavia Moves Into 2nd Place as Lockport Lengthens Lead,” Buffalo Evening News, June 30, 1943: 37.

51 Associated Press, “Fans Threaten Umpire in Row at Wellsville,” Elmira Star-Gazette, August 10, 1944: 27.

52 “More Or Less About Sports,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, May 22, 1956: 7. Scull was considered such a lock to make the Washington Senators in 1954 that he was given a Topps baseball card that year, but an injury kept him from the majors.

53 Greengrass was born in Addison, New York, less than an hour’s drive from Wellsville.

54 Greengrass was 6-for-18 (.333) against Littlefield with one home run and five RBIs. The pair were both in the National League from 1954 to 1956.

55 Future Hall of Famer Niekro is a footnote in the history of Wellsville baseball, having made just 10 appearances with the Braves as a 20-year-old rookie in 1959. He went 2–1 with a 7.46 ERA.

56 It might be noted that Sepkowski was 29 years old in 1953 and 30 in 1954, which made him significantly older than the average PONY League player; he’d been out of the majors since 1947. The average PONY League batter in 1953 was 21½ years old, while the average pitcher was even younger – 20½.

57 DeLeon didn’t make the majors, but his son, also named Luis DeLeon, did.

58 Bob Ellis, “A Baby Brave is Born (1956),” Wellsville Daily Reporter, August 20, 1976: 10, https://nyshistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=wdr19760820-01.1.10&srpos=38&e=——-en-20–1–txt-txIN———-.

59 “Flag Not Attendance Magnet.”

60 George Pawlush, “The Minor Leagues of My Youth,” When Minor League Baseball Almost Went Bust 1946-1963 (Phoenix, Arizona: Society for American Baseball Research, 2025: 5.

61 Dave Rosenbloom, “Geneva Wins, 2-1, in NYP Playoff Tilt,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, September 5, 1958: 23; “1960 Census of Population: New York,” US Census Bureau, accessed online December 2024: 4, https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1960/population-pc-a1/15611126ch4.pdf.

62 “Buses, Tullar Field are Topics of Board,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, May 10, 1960: 4.

63 Advertisement, Wellsville Daily Reporter, April 25, 1961: 4.

64 “Red Sox Bring Down Curtain with 11-8 Win at Tullar Field,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, September 1, 1961: 5.

65 “Why?,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, August 17, 1961: 4. A week later, Paige skipped out on the Monarchs just before a scheduled appearance in Elmira, New York, because he’d signed a contract with a professional team. Al Mallette, “The Master Showman,” Elmira Star-Gazette, August 24, 1961: 27.

66 “Village to Help Team Within its Legal Limits,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, November 13, 1962: 7; “Vandals Damage Ballpark Stand,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, November 3, 1962: 3..

67 “Paraders Welcome Governor,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, October 25, 1962: 4; Bert Freed, “Campaign Style Changed by Governor Due to Crisis,” Buffalo Evening News, October 25, 1962: III:27.

68 “Estimated 800 See Billy Graham Movie in Tullar Field Show,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, August 6, 1962: 6.

69 “Red Sox to Return Professional Baseball to Wellsville,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, December 13, 1962: 7.

70 “Tullar Field Sporting Bigger, Repaired Clubhouse Facilities,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, April 25, 1963: 7.

71 “Notice to Bidders,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, February 20, 1963: 6.

72 The 1963 team also made the four-team postseason playoffs, but was eliminated by Jamestown in the first round. “Scores and Standings,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, September 6, 1963: 1D. Only the league’s top two teams took part in the postseason in 1964, leaving Wellsville out in the cold. “Prexy’s Vote Ousts Locals from Playoffs,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, September 3, 1964: 7.

73 “Conigliaro Named,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, August 13, 1963: 5.

74 “Red Sox Tie Home Run Mark on Wallops by Wade, Nash,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, August 11, 1964: 7; final total for 1964 taken from Baseball-Reference. The New York-Penn League, which played roughly a 130-game season in 1964, switched to a short-season format of about 78 games for the 1967 season.

75 Frank Cady, “Homers Highlight 16-7 Win,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, June 5, 1961: 5.

76 Frank Cady, “Homers – 10 – Brighten Game,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, May 15, 1963: 7.

77 “Trips Rip Sox, 16-11; Nine Four-Baggers Equal Loop Record,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, May 28, 1964: 7.

78 Chuck Ward, “Two Grand-Slam HRs in 12-Run 2nd Inning Pace 24-15 Sox Win,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, May 21, 1965: 8.

79 Chuck Ward, “Dorsch Rips 3 HRs, but Sox Bow, 17-16, In Battle with Trips,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, July 27, 1965: 8.

80 “Jimtown Righthander Equals Loop K-Mark,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, May 16, 1964: 5; Chuck Ward, “Haverly Hits Harmful HR,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, June 5, 1965: 6.

81 “Strikeout Record Falls as Sox Go 13 Innings Before Tipping Batavia,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, August 10, 1964: 5.

82 “Mets Tip Sox in Final Game at Tullar Field,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, September 5, 1964: 5; “Congratulations on a Good Season,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, September 1, 1964: 2; Chuck Ward, “Athletic Amblings,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, September 10, 1965: 8. The 3rd edition of the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball (Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff, editors; New York: Baseball America, 2007) provides different attendance numbers for 1964 (20,083) and 1965 (18,145).

83 “Ball Park Remodeling Laid Before Trustees,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, July 23, 1963: 5.

84 “Immediate Action Ordered to Halt Tullar Field Stench,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, August 13, 1963: 5.

85 Chuck Ward, “Athletic Amblings,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, April 5, 1965: 8.

86 Chuck Ward, “Boston Announces Wellsville Franchise Transfer to Oneonta,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, August 30, 1965: 8.

87 Chuck Ward, “Locals Record 4-3 Decision Over Pirates,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, August 31, 1965: 8. The box score, printed on the same page, also did not include an attendance figure.

88 Associated Press, “NY-P Washed Out,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, September 1, 1965: 8; Chuck Ward, “Athletic Amblings,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, September 2, 1965: 8.

89 “Equipment Taken from Tullar Field,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, March 19, 1966: 3; Mickey Martelle, “Recreation, Fire, Police Quarters Are Scheduled for Tullar Field,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, December 29, 1966: 1. The latter story mentions the poor condition and condemnation of the grandstand.

90 “Surrenders Deed” (photo and caption), Wellsville Daily Reporter, January 6, 1967: 1. Angie Tullar died in January 1932, and her son Bayard in March 1945. Associated Press, “Philanthropist Dies,” Poughkeepsie (New York) Eagle-News, January 11, 1932: 1; “Death of Wellsville Man,” Potter Enterprise, March 22, 1945: 4.

91 “The End Is Near” (photos and caption), Wellsville Daily Reporter, January 9, 1967: 8; “Steps to Nowhere,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, January 19, 1967: 8; “Village Board Sells Former Dump to Town,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, January 24, 1967: 5.

92 Gary Hicks, “New Fire-Police Complex Is Nearing Completion,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, September 4, 1971: 3; Matt Leone, “2,000 Cheer Opening of Arterial,” “Surrenders Deed” (photo and caption), Wellsville Daily Reporter, October 27, 1977: 1.

93 In an editor’s note in May 1970, an unnamed editor representing the Wellsville Daily Reporter wrote: “Tullar Field stinks! … No other field played upon by the Wellsville football team approached Tullar Field for roughness and inadequacy.” “Worth Talking About,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, May 9, 1970: 6, https://nyshistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=wdr19700509-01.1.6&srpos=7&e=——-en-20–1–txt-txIN———-; Phil Ameele, “Wellsville Chamber Asks Baseball Info,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, April 26, 1973: 3, https://nyshistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=wdr19730426-01.1.3&srpos=51&e=——-en-20–1–txt-txIN———-.

94 “Wellsville Parade Winners Are Listed,” Olean Times-Herald, July 6, 1976: 4.

95 Geri Welch, “Tullar Field Lights Shine Friday Night,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, October 28, 1975: 3; “Tullar Field’s the Scene for Halloween,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, October 19, 1976: 3, https://nyshistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=wdr19761019-01.1.3&srpos=27&e=——-en-20–1–txt-txIN———-.

96 Sue Goetschius, “Tullar Field Dedicated,” Olean Times-Herald, June 4, 1979: 5.

97 “Wellsville Recreational, Sporting and Outdoor Resources Summary,” Allegany County website, accessed December 2024, https://www.alleganyco.gov/wp-content/uploads/AppendixF.pdf.

98 Kathryn Ross, “Wellsville Celebrates NYS Champion Softball Team,” Olean Times-Herald, posted June 25, 2024, https://www.oleantimesherald.com/news/wellsville-celebrates-nys-champion-softball-team/article_5c5cf3e6-3307-11ef-a26c-effad1fbf293.html.