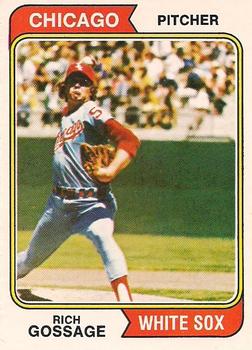

Rich Gossage

Rich “Goose” Gossage was “the type of relief pitcher that has become extinct,” as Murray Chass of the New York Times put it in 2008.[1] Today’s closer typically has the mission of pitching one inning. In 1978, when the fearsome, hard-throwing righty was the mainstay of the bullpen for the World Series champion New York Yankees, he pitched 134 1/3 innings in 63 appearances. By contrast, Mariano Rivera’s 15-year high as Yankees closer has been 80 2/3 innings, in 2001.

Rich “Goose” Gossage was “the type of relief pitcher that has become extinct,” as Murray Chass of the New York Times put it in 2008.[1] Today’s closer typically has the mission of pitching one inning. In 1978, when the fearsome, hard-throwing righty was the mainstay of the bullpen for the World Series champion New York Yankees, he pitched 134 1/3 innings in 63 appearances. By contrast, Mariano Rivera’s 15-year high as Yankees closer has been 80 2/3 innings, in 2001.

“I take exception to Mariano being called the best reliever ever,” Gossage told Chass. “But do what we did and we’ll be able to compare apples to apples. I don’t take anything away from Mariano; he’s great. But what these guys do today is easy compared to what we did. It takes three guys to do what I did.”[2] He did it mainly with pure heat: The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers rated Gossage’s fastball behind only Nolan Ryan’s for the 1975-79 period. His size and aggressive demeanor on the mound further intimidated batters.

The Baseball Hall of Fame inducted the Goose in 2008, making him one of just five relief specialists in Cooperstown as of 2011 (the others are Hoyt Wilhelm, Rollie Fingers, Dennis Eckersley and Bruce Sutter). His accomplishments across 22 major-league seasons include:

* 310 saves. That may seem low by today’s standards – it ranked 20th on the all-time list at the end of the 2013 season. But it was fourth all-time when he retired. What’s more, he recorded four or five outs in 68 of those saves, six to eight in 101 of them, and nine or more outs in 24 more.[3]

* A 124-107 record

* 1,502 strikeouts in 1,809 innings.

Gossage’s most productive span was from 1975 through 1986, as he registered 20 or more saves in all but one of those seasons. His 26 saves in 1975, 27 in 1978, and 33 in 1980 led the majors.

Richard Michael Gossage was born on July 5, 1951, in Colorado Springs, Colorado. He was the fifth of six children born to Jake Gossage and his wife Sue. Jake was “a gold prospector who never quite struck it rich. Because of this, the Gossage family of six children had to live in a one-bedroom house.”[4] Jake, who also worked on and off as a coal miner and landscaper, liked to hunt and fish and roam in the mountains.[5]

Jake Gossage died when Rick – as his family called him[6] – was a junior at Wasson High School in Colorado Springs.[7] Yet the father-son relationship laid an important foundation for the future star’s career. Each evening before dinner, Jake invited the boy to play catch in the backyard. Every five throws Jake took off his glove and massaged his hand. Rick complained with his glove in front of his chest. “Come on Dad, throw the ball.” After dinner they sat on the porch and talked a lot about great stars such as Mickey Mantle, Willie Mays, Bob Feller, and Joe DiMaggio.[8] In 2000, Gossage said, “I still thought players like Mickey Mantle had to be fictitious people.” Jake replied that the boy was going to play in the majors because of his strong right arm.[9]

In 2007, Gossage added that he never played as well as his teammates in the sandlot games. They had very good fielding and batting skills. Jake also emphasized the importance of discipline and practice.[10]

Mother Sue also played a key role in her son’s early development as a player. After one tough loss as a schoolboy, she sat with Rich on the bed and hugged him. She said, “It’s okay to compete. But you know something? It’s very important to respect the rival. Because that’s the essence of sports and life.” After a rival pitcher hit Gossage in the ribs with a pitch, and he was tempted to retaliate in kind, Sue whistled from the crowd – and instead the teenager threw a strikeout pitch. While returning to the dugout, he looked up to see his mother beaming in the stands.[11]

Gossage’s career at Wasson High impressed the Chicago White Sox, who took him in the ninth round of the 1970 amateur draft. Scout Bill Kimball called him Rich, which stuck with the press and fans.[12] The pitcher first went to the Sarasota White Sox in the Gulf Coast Rookie League, but after striking out 21 men and walking just four in 16 innings, he moved up to Appleton in the Midwest League (Class A). In 10 games with the Foxes he had modest results (0-3, 5.91).

A year later he opened eyes with his numbers as a starter for the same Appleton Foxes. He won 18, lost just 2, and posted a 1.83 ERA with 149 strikeouts in 187 innings. The reason for his success was an off-speed delivery, a slurve that Johnny Sain (White Sox pitching coach) and Chuck Tanner (the big club’s manager) taught him the year before in Sarasota. Gossage had 15 complete games, seven shutouts, and led the league in ERA and wins. He was Topps’ Midwest League Player of the Year. He was invited to major league camp in 1972.

During the first days of that 1972 spring training, Gossage was amazed how his roommate, Tom Bradley, took the mound with sunglasses and pitched very comfortably. One evening, Gossage asked Bradley about the sunglasses and Bradley responded by saying how he thought Gossage’s neck stuck out while looking for the sign from the catcher. It reminded him of the movement of a goose. That comment was published by the Chicago media and so “Goose” Gossage was christened.

One of those days in camp, Tanner called Gossage to his office and told him they were going to send him back to the minors. “I wasn’t,” said Tanner in 2008, “but wanted to shake him up a little. He said, “I’m better than any pitcher here.’ We went at it. I grabbed him and pinned him against the wall. I said, ‘OK, you’re pitching today. Show me something! All I hear is talk, talk.’ I said to myself, ‘This is going to be fun.’ During three innings he struck out every batter he faced and I believe threw just two balls. He was so sky-high. He’d come back to the dugout and just stare at me, but I’d look straight ahead. After that, I told him, ‘Well, you were OK. I guess I’ll take you north.’ He started smiling.”[13]

Gossage’s version: “I remember being called into his office at Payne Park in Sarasota. He said, ‘I want to show you a list.’ My name was crossed off. I said, ‘What does that mean?’ He said, ‘As of now, you’re not going north. You’re not going to make the team.’” We got into it pretty good and he said, ‘You haven’t improved. You’re pitching the same way you did when I first met you.’ It got heated and Johnny Sain separated us. I said, ‘I’m the best pitcher you got.’ He fired back, ‘Why don’t you go out and prove it?’ And I did.”[14]

Even though Gossage had a 7-1 record in 1972 as a rookie, he had control trouble – five walks per nine innings fueled a 4.28 ERA. That season, Dick Allen, Chicago’s star first baseman, often went to the mound and talked to Gossage. “Hey, let ’em know you’re out here. Don’t be afraid to throw one under their necks. Not only will the batter see it, but also everybody on the bench who’s going to hit against you.” Tanner said that Dick Allen was a kind of manager in the field. Gossage said that the most important people for him in becoming a real pitcher were Tanner, Sain and Allen. “When I came to the big leagues Chuck said, ‘Son, if you don’t make that hitter as uncomfortable as you can, you might as well go do something else.’”[15]

Unfortunately, Gossage was even wilder in 1973 and spent several weeks from late July through mid-September with the Triple-A Iowa Oaks. That winter, the White Sox sent him to play ball with the Ponce Leones in Puerto Rico. He was more successful in 1974, though he pulled a muscle in his side in May and had to go to Appleton to get back in playing shape.[16] When he returned, he was in the majors for good. That September, The Sporting News recognized, “[Tanner]’s still high on the sometimes brilliant Rich Gossage.”[17]

In 1975, Tanner decided to focus Gossage (who had made several spot starts in his first three seasons) and Terry Forster (who had also been a starter on occasion) on the bullpen. “Tanner might have been ahead of his time, but his decision was rooted in both long-term vision and short-term expediency. He knew it would be a shock to a hitter’s system to see Gossage grunting and snorting in 98 mph increments after seven innings of watching Wilbur Wood’s knuckleball and Tom Bradley’s curve.”[18]

Forster spent most of the year in the disabled list, and the Goose had his first great season. He led the American League with 26 saves. He got 130 strikeouts in 141 2/3 innings and allowed 99 hits (only three home runs). All this earned him his first appearance in the All-Star Game; he was named nine times and got into six games.

The next season, Tanner got fired by the White Sox and the Oakland A’s named him their manager. Owner Bill Veeck brought in Paul Richards as Chicago’s new manager. Gossage was sent back to the starting rotation and lost 17 games, struck out just 135 in 224 innings, and allowed 214 hits. “I don’t know if I have the patience to be a starter,” he said in 1981. “I almost went nuts waiting five days to pitch.”[19] The White Sox also lost 97 games in 1976.

In the off season Veeck traded Forster and Gossage to the Pittsburgh Pirates for outfielder Richie Zisk and pitcher Silvio Martínez. Zisk reached career highs of 30 home runs and 101 RBIs in his one season with the White Sox but was never as productive again. Tanner, who had moved on to become the Pirates’ skipper, was behind that transaction. He knew Gossage’s best seasons were in the near future. In 1977, the Goose had probably his single most dominant season. He posted a record of 11-9 with 26 saves and a 1.62 ERA, striking out 151 in 133 innings. He shared duties with Kent Tekulve and Grant Jackson, forming one of the most dominant relief corps in baseball. The contrast between the submariner Tekulve’s sinker and Gossage’s high heat was very hard on opponents.

When Gossage found out that the Pirates decided not to sign him after the 1977 season – their offer wasn`t even closer to what he wanted – he got very sad. He liked the place, the team and playing for Tanner. So he and his wife, Corna – née Cornelia Lukaszewicz, his hometown sweetheart, whom he married on October 28, 1972[20] – packed their belongings in their Pittsburgh apartment. Three Rivers Stadium was the last stop; there he emptied his locker. Chuck Tanner wished him the best in the future; he said the Goose was going the right way. “I put my bags in the car and just sat there and cried.”[21]

Gossage signed a six-year, $3.6 million contract with George Steinbrenner and the New York Yankees on November 22, 1977. The Yanks had the reigning AL Cy Young Award winner, Sparky Lyle. This move eventually led third baseman Graig Nettles to say about Lyle: “He went from Cy Young to sayonara.”

Gossage lost three of his four first games with the Yankees. In that stretch, he pitched three innings once and three and two-thirds innings twice. Yet the fans, the front office, and even catcher Thurman Munson were wondering what was going on. He lost the first game of the season after giving up a home run to none other than Richie Zisk, then with Texas. His next game was a blown save against the Milwaukee Brewers. Then he made errors on successive sacrifice bunts. He got a lot of boos when returning to Yankee Stadium and remembered how centerfielder Mickey Rivers jumped on the hood of the bullpen car to try to stop him from entering a game.[22]

Despite also blowing the 1978 All-Star Game, Gossage found his form, leading the American League with 27 saves. He helped the Yankees to come back after trailing Boston by 14 1/2 games in the American League East. He saved a one-run lead in the one-game playoff against the Red Sox. He went 2 2/3 rather rocky innings, finally getting Carl Yastrzemski to pop up to Graig Nettles to end the game.

“My legs were shaking,” Gossage later told author Dick Lally. “I’d never come close to playing in a game of that magnitude. Never had a feeling like that before. I told someone it was like being led in front of a firing squad. Yaz was the last guy I wanted to face in that spot. I had to calm down, so I started talking to myself. I thought, ‘All right, what’s the worst thing that can happen here?’ And my answer was, ‘I’ll be home in Colorado tomorrow looking at the mountains.’ Suddenly I was very calm.”

“That pitch he threw me that afternoon,” Yaz later recalled, “came in even faster than I thought.” “I can’t tell you how hard I threw that pitch,” Gossage remembered, “but it might have been one of the hardest pitches I’ve ever thrown.”[23]

In that first season with the Yankees, once he relieved at the start of the seventh and pitched the final seven innings of a 13-inning game. Later in the season he pitched seven innings again in a 17-inning game. Sixteen times he pitched three innings or longer; 35 times in his 63 games he went two or longer.

“There were a lot of times we pitched when we were behind a run,” Gossage told Murray Chass. “We were brought in to get out of a jam and then had to keep pitching, and keep the game in check so it didn’t turn into a blowout.”

“It was grueling, the way we were used,” he said. “We were abused. Nobody worried about our arms falling off. I didn’t. Today’s pitchers are babied. I don’t agree with pitch counts. I never have. I don’t need a pitch count to tell me if a guy is tired. They’re babied too much. They don’t build up any endurance.” Pitchers are like racehorses, Gossage said. “If you train a horse to race half a block, that’s all he’s going to be able to run.”[24]

In 1978, Gossage got a win apiece in the AL Championship Series against Kansas City and the World Series against Los Angeles. The Yankees did not win the AL East in 1979, though, and one factor may have been that their top fireman was lost to the club for nearly three months after tearing ligaments in his thumb during a shower-room scuffle with teammate Cliff Johnson. Except for that, he might well have set a personal single-season high in saves.

Gossage appeared in the postseason in two other years for the Yankees. In 1980, he lost one game as the Royals advanced to the World Series behind a booming George Brett homer off the Goose. In 1981, he recorded six saves against Milwaukee, Oakland, and the Dodgers. The 1981 season was also when Gossage first grew a mustache. It soon became the Fu Manchu version that he still sports today. “I didn’t grow it to be intimidating,” he said in 1997. “I grew it to tick off Steinbrenner.”[25] (Yankees team policy stills calls for mustaches to remain in line with the upper lip.)

The 1982 season also featured a memorable Gossage rant, “All you guys with pens and tape recorders, you can turn them on and take it upstairs to the fat man [Steinbrenner] because I’m sick of this negative stuff.” In January 1984, he signed as a free agent with the San Diego Padres because of more frequent clashes with The Boss. San Diego went to the World Series that year, but the Goose was not effective in his two outings against the Detroit Tigers. He remained the Padres closer through 1986. Among other things, Pete Rose – in his final at-bat in the majors – struck out against him that summer. In 1987, however, Lance McCullers got more save opportunities.

In February 1988, the Padres traded Gossage to the Chicago Cubs, who needed a new closer after dealing away Lee Smith. He still got 13 saves that year, but that was his last in double digits. After one year in Chicago, “experimenting with off-speed pitches to compensate for a diminished fastball,” he was released.[26] The 1989 season featured a stop with the San Francisco Giants and a brief return to the Yankees. He was out of baseball for part of 1990, but in July, he signed with the Fukuoka Daiei Hawks in Japan. He was 2-3 with eight saves and a 4.40 ERA.

Returning to the U.S., he was with the Texas Rangers for one season and the Oakland A’s for two, setting up Dennis Eckersley. His last season, at age 42, was 1994, when he pitched for the Seattle Mariners. His last save came on August 8, not long before the strike ended the season. It was a true Goose Gossage save: a perfect three innings against the Rangers.

Gossage then returned to Colorado Springs. He and Corna had three children: Jeff, Keith and Todd, all of whom are now adults. They lived in a tonier area than where he grew up, but Gossage was modest about it. “The school district decided it for us,” he said. “We’re not status people and never have been. I came from a poor family, but we had a lot of love for each other.” During Rich’s playing career, he stayed close to his family, bringing them on the road.[27]

In 2000, the Goose saw only one pitcher similar to him among the new generation: Randy Johnson, the hard-throwing, aggressive left-hander. “If I was a hitter and I knew what I know about Randy Johnson, I’d never get in the box,” Gossage said of his former Seattle Mariners teammate. “He’s scary. Heck, if I’m a batter, I wouldn’t hit against myself. We both pitch with a task and we’re going to accomplish it.”[28] That year, Gossage also published his memoirs, The Goose Is Loose (co-authored with Russ Pate).

Gossage’s Hall of Fame induction took longer than he would have liked. In 2006, he said, “It’s just very insulting to me that Dennis Eckersley would go in before Bruce Sutter and myself. I mean, it’s nothing against Eckersley. He belongs in the Hall of Fame. But Sutter and me, we changed the role of the relief pitcher.”[29]

The only other disappointment was that his mother had passed away a year before. Chuck Tanner and Dick Allen got special invitations from the Goose to attend the ceremony. “I’m picking Dick up and we’re driving to Cooperstown together [from New Castle, Pennsylvania,” said Tanner. Tanner added, “I had to baby Goose, use a lot of psychology and move him along, but I knew how great he could be. I had in the back of my mind all along he was best-suited for the bullpen.”[30] Later, in another interview, Tanner said, “I know how competitive he was and how he made me successful. He made me a good manager. I didn’t make him. I just kind of steered and guided him a little here and there.”[31]

As of 2011, Rich “Goose” Gossage remains active in youth sports in Colorado Springs. For several years, he has served as an instructor for the Yankees in spring training. At 60 years old, he reckons that he can still throw 80 miles per hour.

Many special thanks to fellow SABR member Rory Costello, whose contribution was very important to complete this work – so important that we wouldn’t be reading this piece without his efforts.

October 27, 2011

Sourceswww.goosegossage.com

Bodley, Hal.“Gossage credits former skipper.” MLB.com, July 24, 2008.

Chass, Murray. “A Reliever From the Old School Awaits His Hall of Fame Day.” New York Times, January 7, 2008.

Crasnick, Jerry. “Tanner backing Gossage.” ESPN.com. December 27, 2007.

Gossage, Rich. “Goose Gossage’s early struggles as a Yankee.” Baseball Digest, August 2005. Drawn from The Goose Is Loose, Ballantine Books, 2000.

Moss, Irv. “Where Are They Now? Former Reliever Goose Gossage.” Baseball Digest, October 2000: 58-62. Originally published in the Denver Post.

Sandomir, Richard. “Dick Allen’s Pitching Advice to Goose Gossage.” New York Times, July 26, 2008.

Sarver, Drew. “Baseball Digest Birthdays: Goose Gossage.” www.baseballdigest.com, July 5, 2011.

Yandek, Chris. Rich “Goose” Gossage. www.cyinterview.com, May 4, 2007.

[1] Chass, op. cit.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Verducci, Tom. “Recognition deserved.” SI.com, July 27, 2008.

[4] Aaseng, Nathan. Baseball’s Ace Relief Pitchers. Urbana, Illinois: Lerner Publishing, 1984: 45. Nack, William. “Goose!” Sports Illustrated, September 28, 1981.

[5] Nack, op. cit.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Moss, Irv. “Where are they now? Former reliever Rich Gossage.” Baseball Digest. October 2000.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Nack, op. cit.

[13] Bodley, op. cit.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Holtzman, Jerome. “Santo Sparkles as Chisox’ New Keystoner.” The Sporting News, May 18, 1974: 13.

[17] Dozer, Richard. “White Sox Promote Only Two Rookies.” The Sporting News, September 21, 1974: 18.

[18] Crasnick, Jerry. “Tanner backing Gossage.” ESPN.com. December 27th, 2007.

[19] Nack, op. cit.

[20] Ibid.; The Celebrity Who’s Who, 1986: 141.

[21] Bodley, Hal. “Gossage credits former skipper.” MLB.com, July 24, 2008.

[22] Sarver, op. cit.

[23] Belth, Alex. “Hard-throwing Gossage was scary — and scary good.” SI.com, January 7, 2008.

[24] Chass, op. cit.

[25] Miller, Jeff. “Little Presence, Great Future.” Fort Lauderdale Sun-Sentinel, March 30, 1997.

[26] “The feared fastball is gone, and so is ‘Goose’ Gossage.” Associated Press, March 29, 1989.

[27] Moss, op. cit.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Graziano, Dan. Newark-Star Ledger, January 9, 2006.

[30] Bodley, op. cit.

[31] Crasnick, op. cit.

Full Name

Richard Michael Gossage

Born

July 5, 1951 at Colorado Springs, CO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.