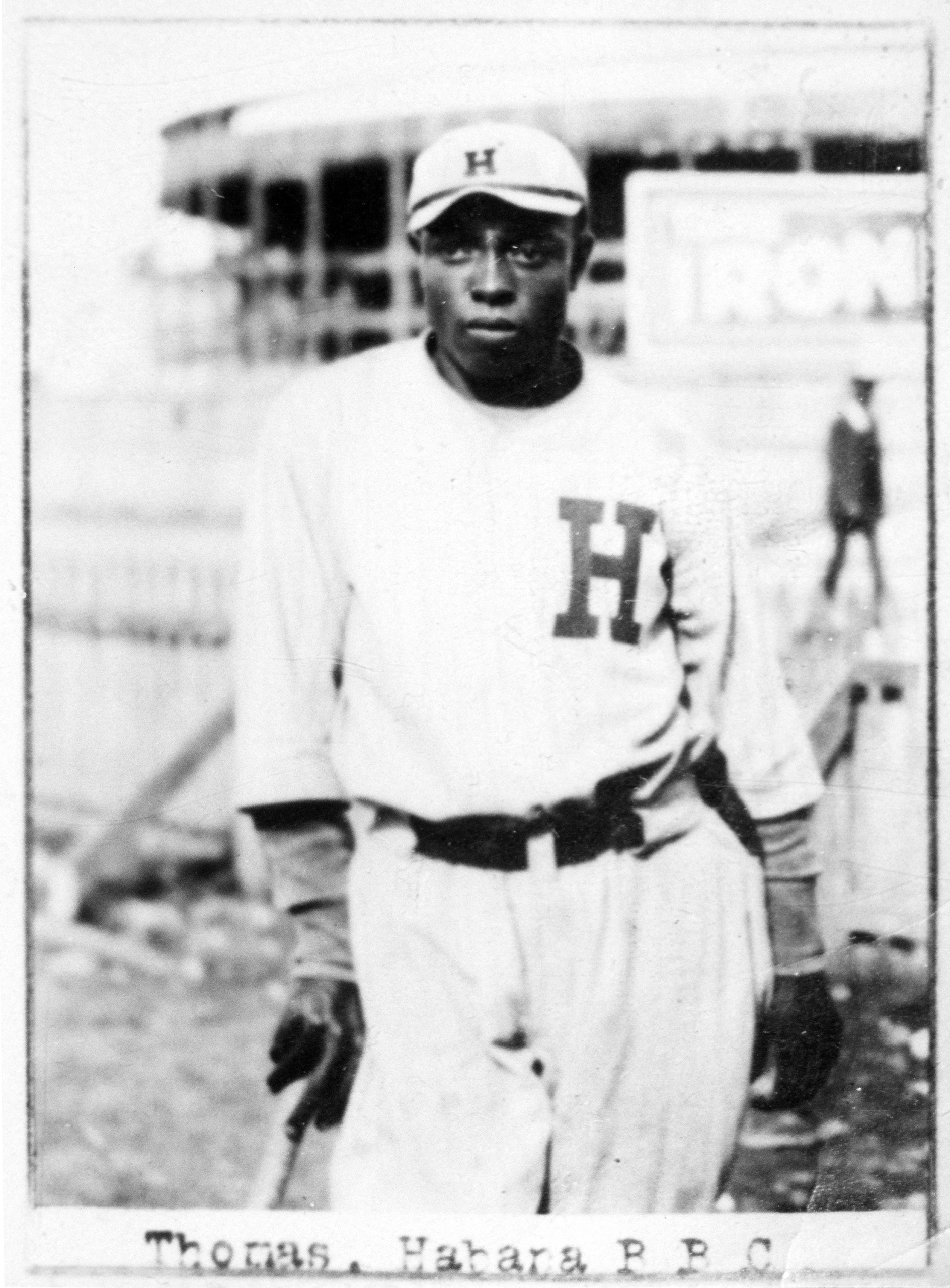

Clint Thomas

If you page through the annals of Black baseball, you will come across watershed moments – the “First Colored World Series,” Yankee Stadium’s first game between Black ball clubs, Satchel Paige’s first professional no-hitter – and you will find a single face peering across the ages. Historic moments seemed to cling to Clint “The Hawk” Thomas over his 19-year career in professional baseball, and in the waning years of his life, he played a significant role in preserving those memories.

If you page through the annals of Black baseball, you will come across watershed moments – the “First Colored World Series,” Yankee Stadium’s first game between Black ball clubs, Satchel Paige’s first professional no-hitter – and you will find a single face peering across the ages. Historic moments seemed to cling to Clint “The Hawk” Thomas over his 19-year career in professional baseball, and in the waning years of his life, he played a significant role in preserving those memories.

Clinton Cyrus Thomas was born on November 25, 1896, to James and Lutie (Beaver) Thomas in Greenup, Kentucky. The family quickly grew, and by 1910, the Thomases had six children, four boys and two girls. Clint, the oldest, felt pressure to care for the family when his father struggled to find work, so at the age of fourteen, he moved to Columbus, Ohio, where his mother’s family lived, and entered the workforce.1

In 1918 two events reshaped Thomas’s professional and family life. First, he married Virginia Johnson in June.2 Then, he enlisted in the United States Army on September 24 and reported for duty at Camp Sherman in November. That fall, the Influenza Pandemic beset the camp and nearby Chillicothe, Ohio.3 Thomas, upon arriving at the camp and seeing the conditions, “ran off back to Columbus.”4 Thomas soon reconsidered and returned to Camp Sherman, where he served in the 158th Depot Brigade. Thomas subsequently earned a promotion to corporal and then sergeant before being honorably discharged on December 22, not long after the First World War ended. According to Thomas, his unit narrowly avoided being sent to Europe. “We had our duffel bags, and the train was out there; then they said the Armistice was signed, and that was it.”5

Thomas returned to Columbus where he began his professional baseball career in earnest. He joined a semi-professional club called Bower’s Easterners, which were reigning Ohio state champions.6 Although press coverage of the Easterners was scant, Thomas turned enough heads to climb the professional baseball ladder. Prior to the 1920 season he travelled to New York and tried out for John Henry “Pop” Lloyd and the Brooklyn Royal Giants. He won a spot on the roster as an infielder.

Thomas struggled to adapt to the rigors of full-time professional baseball. He later admitted that he was “scared to death,” but that the older players helped him settle in.7 Lloyd, in particular, was renowned as a mentor to young stars, and Thomas followed the player-manager to the Columbus Buckeyes for the 1921 season. In total, Lloyd and Thomas played together for five different Negro League clubs across parts of six seasons.

The move back to the familiar environment of Columbus seemed to invigorate Thomas. Even among the renowned company in Rube Foster’s Negro National League, Thomas stood out. In his first full season (the league’s second), he ranked in the top 15 in OPS, homers, and stolen bases and the top 10 in RBIs, hits, sacrifices, and slugging percentage; he led the league with 18 triples.

The 1921 season set the bar for Thomas offensively. “He attacked the ball the way a dog attacks raw meat,” remembered Ted Page. Monte Irvin lauded Thomas’s hustle and speed, calling him a “Pete Rose-type player.” Defensively, though, Thomas had yet to find a good fit. Among 178 qualifying players in the NNL that season, he finished dead last in fielding WAR. “I was a second baseman, but I wasn’t a good second baseman,” Thomas later recalled.8

The Columbus Buckeyes dissolved at the end of 1921, and their players scattered throughout the Negro National League and other independent clubs. Thomas signed with the Detroit Stars where he would play under Bruce Petway, a standout catcher and mentor.

Thomas’s stint in Detroit established his persona as a player. First, Petway moved him from second base to the outfield.9 Then, seeing Thomas’s fielding prowess, the manager dubbed him “The Hawk,” a nickname that stuck with Thomas well into retirement. “We were playing a doubleheader [the day Thomas moved to right field] and in the first game I was all over the outfield. I was running in front of the center fielder to make catches. After the first game, the manager [Petway] called me over and told me he was moving me to center field. I made a couple of good plays in that game… That’s when I got the nickname.”10

The establishment of the Eastern Colored League in 1923 upended Detroit’s roster. Sensing a budding rivalry, Foster attempted to woo the new league into an affiliation with the NNL, but ECL president, Ed Bolden, balked at the travel costs to the Midwest11 and instead lured players east with promises of pay increases. The ECL offered Detroit players $350 to jump leagues, so Thomas, who made just $200 per month with the Stars and supplemented his income with an offseason job with Ford Motor Company, joined Bolden’s Hilldale club.12 Hilldale played in Darby, Pennsylvania, just outside of Philadelphia, and filled its club with young stars and veterans alike; Thomas, Frank Warfield, Judy Johnson, and Biz Mackey supplied the youth while Lloyd (who served as player-manager), George Johnson, and Louis Santop provided veteran leadership.

Hilldale, a historically strong club, quickly turned into a dynasty, but the players were not always content. Toward the end of the 1923 season, Thomas petitioned Bolden and Lloyd for a raise. The owner agreed, but Lloyd turned Thomas down. Bolden, for other reasons, relieved Lloyd of managerial duties and banned him from the team in early October.13 Nevertheless, Hilldale won the inaugural ECL pennant, beginning its four-year reign as circuit champions.

Despite the tensions between Thomas and Lloyd, the two traveled together to Cuba to participate in the Cuban winter league with the Habana club. The offseason play was professionally and financially good to Thomas. Thomas hit .310 across five seasons in Cuba, three played alongside Lloyd.14 Thomas claimed that, in his first season, players’ pay would be determined by ticket sales and that he “played to much bigger crowds in Cuba than in the United States.” He took home $7,000 after the 1923-24 season; the Cuban League moved to a salary structure in subsequent years.15

Like most players of his era, Thomas played year-round. In addition to his seasons in Cuba, he played at least one season (1927-28) with the Philadelphia Royal Giants, an offshoot of Hilldale, in the integrated California Winter League and spent time in Florida playing in the Hotel League (also known as the Coconut League.)16

In 1924, Thomas’s slugging played a significant role in Hilldale’s second pennant and trip to the “First Colored World Series” against the Kansas City Monarchs. Hilldale lost the series five games to four (with one tie). Although the statistics may indicate that Thomas underperformed in the championship (.212 with one extra-base hit), he passed the “eye test” for many reporters and fans. Dizzy Dismukes, who covered the series, remarked that Thomas was “the most improved ball player I ever saw” and named the left fielder to his All-Star team.17

Thomas and Hilldale were even better in 1925. The “Darby Daisies,” as Hilldale was known, found themselves in a battle with Oscar Charleston’s Harrisburg Giants, their intrastate rival. The teams jockeyed atop the Eastern League leaderboard for much of the summer with Charleston stirring rumors of schedule manipulation and the influencing of umpires. In a late July doubleheader, the teams came to blows. According to Bolden, the Giants’ Dick Jackson insulted Frank Warfield, who was widely known for his fiery temper. Thomas tried to play peacemaker only to be physically pushed aside by Charleston.18 The fight fueled Hilldale, who never relinquished their first-place position from that point on.19

Hilldale turned the tables on Kansas City in the best-of-nine World Series rematch and stormed to victory with five wins in six games. Pitching proved to be the determining factor in the series. With future Hall of Famer “Bullet” Joe Rogan sidelined for Kansas City, Hilldale’s staff took full control.20 Rube Curry, Nip Winters, Phil Cockrell, and Script Lee combined for a 1.64 ERA. Offensively, Mackey, who clubbed five extra-base hits in 25 at-bats, and Otto Briggs, who rapped out 12 hits, drew much of the attention, but Thomas provided timely hitting and aggressive base running that swayed the series. In Game One, with Hilldale trailing 1-0 in the seventh, Thomas worked a leadoff walk, went first-to-third on Johnson’s single, and scored on a sacrifice fly to tie the game. A similar sequence played out in Game Two with Thomas’s resulting run coming on a squeeze play. Thomas, though, saved his power display for the home crowds. In the Baker Bowl in Philadelphia, he launched a pivotal RBI double to put Hilldale ahead, 2-0, in the fourth inning of Game Five, and in the fourth inning of Game Six, he again doubled and later came around to score the first run of the series-clinching win.21

Over the next three seasons, Thomas remained a fixture with Hilldale, recording career highs in hits (104), RBIs (79), stolen bases (25), and home runs (9) in 1926.22 After losing the pennant, Bolden offered Thomas and star pitcher Winters to Harrisburg as trade bait for Charleston in 1927, but both Hilldale players refused to report.23 Bolden subsequently released Thomas after successfully acquiring Charleston in 1928. Thomas joined the Atlantic City Bacharachs for the remainder of the season and into 1929.

The Great Depression severely affected the Negro Leagues. The Eastern League and its descendent, the American Negro League, collapsed in the late 1920s, and the Negro National League (the Midwest contingent) faltered in 1931.24 Thomas, like many Black ballplayers of the time, ventured into the world of independent baseball. The latter half of Thomas’s career would be marked by uncertainty, publicity stunts, and endless barnstorming.

Thomas’s one-year stint with the New York Lincoln Giants in 1930 served as a transition from affiliated to independent ball. He and Atlantic City teammate Fats Jenkins joined Charlie Smith as one of the most highly touted outfields in the sport. So strong were they that Turkey Stearnes, a future Hall of Famer in the prime of his career, sat the bench. The team won 13 straight games at home to open the season and, in one two-day stretch, scored 72 runs over four games. This success led to the team’s inclusion in an exhibition doubleheader on July 3, 1930, at Yankee Stadium against the Baltimore Black Sox, the first games between Black ball clubs at the venue.

Despite being unaffiliated with the Negro National League in 1930, the Giants faced off against Charleston’s Homestead Grays, another barnstorming team, to decide an East Coast champion. The ten-game series travelled between Forbes Field in Pittsburgh, Yankee Stadium, and Bigler Field in Philadelphia.25 Thomas fared well in the series, hitting .303 with three doubles, a homer, and six runs scored. Still, the Giants fell six games to four.26

Prior to the 1931 season, entertainer and celebrity Bill “Bojangles” Robinson recruited many of the Lincoln Giants, including Lloyd, Thomas, and Jenkins, to join his new barnstorming club. The team, which went by a number of names before settling on the Black Yankees, played the majority of their games at Dyckman Oval in Manhattan and Dexter Park in Brooklyn. On occasional major league off-days, the team played at big league stadiums including the Polo Grounds and Yankee Stadium.27 The games at the major league parks were poorly attended and were discontinued midway through the 1931 season.28 Thomas remained with the team through the 1935 season.29

Thomas’s time with the Black Yankees contained two moments that are emblematic of his skill. The first, displaying his clutch hitting and superior fielding, came during the grand opening of Greenlee Field in Pittsburgh on April 29, 1932. Satchel Paige and Jesse Hubbard battled through eight scoreless innings. With two outs in the top of the ninth and a man on third, Thomas blooped a single into right field to give the Black Yankees the lead. In the bottom of the ninth, Josh Gibson came up with two outs. “The mighty Gibson sent a terrific clout to deep center field that looked for an instant like an extra-base hit, but the fleet-footed Thomas was away with the crack of the bat and gathered in the speeding pellet and the first pitchers’ battle was over.”30

The second, highlighting his speed and aggressive base running, took place during an exhibition game against Dizzy Dean on October 17, 1934. Thomas cracked a triple off Dean in the fourth inning. Buck Leonard once quipped, “When [Thomas] got on base, we knew what was in his mind.”31 It helped that Thomas reportedly told third baseman William “Buck” Lai that he could steal home off Dean.32 Dean purported that he “invited” Thomas to take the shot, and the speedy outfielder, all of 37 years old, dashed home ahead of the tag.33

In May 1935, Thomas broke his leg and missed the bulk of the season.34 Thomas lasted three more seasons, playing in the second iteration of the Negro National League with the Newark Eagles and New York Cubans in 1936 and the Black Yankees in 1937 and 1938. Ultimately, the lingering effects of injury and age forced Thomas into retirement.

Thomas stayed in New York and worked as a security guard at the Brooklyn Navy Yard for the duration of World War II. Many of his siblings had settled in West Virginia, and they lured him to the Mountain State, where he gained work as a messenger for the West Virginia Department of Mines and later as a page and staff supervisor at the State Capitol.35 In 1963, he married Ellen O’Dell Smith.36

Forty years after his playing days ended, Thomas looked back and mused: “I’d love to know where my old teammates are, and how they’ve [been] getting along.”37 Tom Stultz, publisher of a weekly newspaper in Thomas’s hometown The Greenup County Sentinel, decided to help Thomas settle those unanswered questions. Stultz, whose family was close friends with Clint’s brother Horace “Choppy” Thomas and his wife Bea, decided to throw a birthday party of sorts in Greenup.38 Stultz collaborated with former Negro Leaguer Monte Irvin, who worked in the major league baseball commissioner’s office, to spread the word. “They called him ‘The Black Joe DiMaggio,’” Stultz remembered. “I thought, ‘This guy should be selling Mr. Coffee machines.’ Instead, he was making coffee.”39

From across the nation, more than a dozen former players flocked to the tiny town on July Fourth Weekend in 1979 to celebrate “The Hawk.” The ballplayers laughed, reminisced, and even played backyard baseball with local kids. The festivities culminated in a banquet where the mood shifted. “The jokes turned to great appreciation,” Stultz recalled. “Everyone was emotional.”40

Bob Feller, who had barnstormed with Black ballplayers in the 1940s, spoke at a banquet, remarking, “All you gathered, who are not in the Hall of Fame, you belong there.”41 Chico Renfroe echoed Feller’s sentiments during the 1980 reunion, which had moved to the larger town of Ashland, Kentucky: “If you would just take a trip to Cooperstown, New York, and see the one table they have set aside for Negro Baseball, then you would know that there is a place for a Negro Baseball Hall of History right here.”42

In 1982, the dream became a reality when a few dozen players helped dedicate the Negro Baseball Hall of History in Ashland. The museum featured memorabilia, newspaper clippings, and exhibits on life in the Negro Leagues. In 1985, the National Baseball Hall of Fame purchased the material and relocated it to Cooperstown.43 Today, the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown and the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City carry on the mission started at Clint Thomas’s birthday bash in 1979.

Thomas, likely the last living member of the great Hilldale teams and one of the last vestiges of the heyday of Black baseball, passed away on December 2, 1990, in Charleston, West Virginia, at the age of 94. Thomas is buried at Cunningham Memorial Park in St. Albans, West Virginia.44

Acknowledgements

This story was reviewed by Thomas Kern and Kim Juhase and fact-checked by Larry DeFillipo.

Photo credit: Clint Thomas, SABR-Rucker Archive.

Sources

The author is indebted to the late Paul J. Nyden’s oral history interview, “Clint Thomas and the Negro Baseball League,” in the October-December 1979 issue of Goldenseal, a magazine dedicated to the preservation of West Virginia history and culture.

All statistics are credited to Seamheads’ Negro League database, unless otherwise noted, and the author consulted contemporary newspaper articles, as well as historical and genealogical databases, to verify anecdotal and second-hand accounts. Thomas’s player file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame also served as an invaluable resource.

Notes

1 Some of Thomas’s recollections are at odds with the historical record. For example, Thomas states that he was one of eight children when he moved out at age 14, and the Thomas family did grow to include eight children. According to census records and birth certificates, though, his two youngest brothers were born in 1912 and 1914, respectively. The author has tried to use both Thomas’s word of mouth and historical records to create the most complete, accurate account of his life. Paul J. Nyden, “Clint Thomas and the Negro Baseball League,” Goldenseal, October – December 1979: 18.

2 Virginia, a divorcee, seems to have had a child from her previous marriage to Charles Johnson. She and a six-year-old son, Charles, are listed as living with Thomas on the 1920 census. US Census Bureau, 1920 Census, Accessed August 28, 2024, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GR6B-79T?view=index&action=view.

3 So many soldiers died at Camp Sherman that Chillicothe designated the Majestic Theater as a temporary morgue. “The Influenza Pandemic of 1918 at Camp Sherman,” National Park Service, April 8, 2020. Accessed May 6, 2024, https://www.nps.gov/articles/influenza-at-camp-sherman.htm.

4 Nyden, “Clint Thomas”: 18.

5 Ibid.

6 “Easterners Win, 9 to 3,” The Chicago Defender, May 10, 1919: 11.

7 Nyden, “Clint Thomas”: 18.

8 Pat Hemlepp, “Clint Thomas Was That Good,” Ashland (Ky.) Daily Independent, July 5, 1979: 15.

9 Although Thomas’s later recollections indicate that an injury to center fielder Jess Barber prompted the move, contemporary newspaper reports suggest that Barber went AWOL during a series in Pittsburgh. The Stars released Barber after the infraction; the former Stars center fielder later made appearances with the Homestead Grays and Harrisburg Giants in 1922. “Monarchs Lead the League!,” The Call (Kansas City, Mo.), July 8, 1922: A7.

10 Hemlepp, “Clint Thomas”: 15.

11 James Overmyer, “1923-29 Winter Meetings: The Negro Leagues Come East,” Baseball’s Business: The Winter Meetings: 1901-1957, Society for American Baseball Research. Accessed May 27, 2024, https://sabr.org/journal/article/1923-1929-eastern-colored-league-winter-meetings.

12 Nyden, “Clint Thomas”: 19.

13 W. Rollo Wilson, “Suspension of Lloyd Made Permanent by Darby Mogul,” The Pittsburgh Courier, October 6, 1923: 7.

14 Habana (1923-24), Almendares (1924-25, 1928-29), Alacranes (1926-27), and Almendarista (1930, short season). Statistics drawn from Jorge S. Figueredo’s definitive Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 1878-1961. Jorge S. Figueredo, Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 1878-1961(Jefferey, NC: McFarland & Company, 2011).

15 Nyden, “Clint Thomas”: 21.

16 “Pros Pick Two All-Star Teams for the Afro,” Afro-American, February 28, 1931: 14. This article explicitly references Thomas playing with the Poinciana Royals in the Hotel League. Several box scores from earlier seasons list an outfielder with the surname of Thomas on both the Breakers and Poinciana, but this player might be Jules Thomas or another unknown player.

17 “Dismukes’ Diamond Dope,” The Pittsburgh Courier, December 27, 1924: 13; Dismukes Picks All-Star Team from Two Contending World Series Clubs,” The Pittsburgh Courier, November 1, 1924: 6.

18“Right Back at You, Mr. Bolden,” The Pittsburgh Courier, August 1, 1925: 12.

19 According to Seamheads, Hilldale and Harrisburg played 72 and 73 league games, respectively, so the alleged disparities in the schedule worked themselves out by the end of the season.

20 Rogan had a freak accident when playing with his son. He somehow got a needle lodged in his knee and required surgery, keeping him out of the series. “Hilldale Club Near the World Championship,” The St. Louis Argus, October 9, 1925: 6; “Hilldale Takes Offensive in East-West Series,” The Pittsburgh Courier, October 10, 1925: 12.

21 Credit to Retrosheet’s play-by-play breakdowns of the 1925 World Series.

22 Granted, these statistics span 94 games according to the Seamheads Negro League Database, significantly more than every other season except 1921.

23 Rumor had it that Winters’s wife persuaded him to decline the trade. William G. Nunn, “Women in Baseball,” New Pittsburgh Courier, July 30, 1927: 18.

24 For more on the effect of the Great Depression on the Negro Leagues, see David Hopkins, “The Black Press and the Collapse of the Negro League in 1930,” Society for American Baseball Research, 2004. Accessed May 9, 2024, https://sabr.org/journal/article/the-black-press-and-the-collapse-of-the-negro-league-in-1930.

25 While some sources indicate that the Philadelphia games took place at Penmar Park, contemporary articles state the contests were held at a ballpark at 13th and Bigler Street. The location is now part of Marconi Plaza, which contains at least two baseball diamonds but no full stadium. The Lincoln Giants made use of the location, which was also known as the “Corley grounds,” throughout the season. “Three Classy Nines Play Home Games Here,” Philadelphia Tribune, April 17, 1930: 10; Dick Sun, “Games Here Today and Friday Chance for Gotham Nine to Catch up,” Philadelphia Tribune, September 25, 1930: 11.

26 These statistics do not include the sixth game of the series, which New York won, 6-4, in Philadelphia. No complete box score seems to exist.

27 “Harlem Stars at Polo Grounds Sunday,” The New York Age, June 6, 1931: 6.

28 William E. Clark, “Playing of Negro Baseball Teams in Big League Parks Has Not Met with Success and Will Be Ended,” The New York Age, July 18, 1931: 6.

29 Because the Black Yankees were an independent team that barnstormed and played clubs of various qualities and levels of professionalism, many of their games are not counted in the official record. Seamheads credits Thomas with 125 total games over seven seasons. It is more likely that he played 400-500 games in that span.

30 “Hubbard Pitches Three-Hit Game to Beat Page (sic), 1 to 0,” New Pittsburgh Courier, May 7, 1932: 15.

31 Hemlepp, “Clint Thomas”: 15.

32 Gary Joseph Cieradkowski, “Clint Thomas: The Hawk,” Infinite Baseball Card Set (blog), November 23, 2019. Accessed May 9, 2024, https://studiogaryc.com/2019/11/23/clint-thomas.

33 Harold Parrott, “Brooklyn Fans Yell Louder, but Don’t Know Baseball, Says Dizzy,” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, October 18, 1934: 22.

34 Irwin N. Rosee, “Eagle Twin Bill Features Return of Great Dihigo,” (Brooklyn) Times Union, May 29, 1935: 3A.

35 Nyden, “Clint Thomas”: 26.

36 At some point, Virginia and Clint divorced. He may have had a second wife, Stella, who is mentioned on Thomas’s WWII draft registration card and featured in an article titled “From New York” in the Chicago Defender, July 18, 1942: 13.

37 “Negro League star Clint Thomas reminiscence’s [sic],” Chicago Defender, February 11, 1978: 19.

38 Although Thomas’s birthday was in November, the organizers used an established Tristate Festival to bring in more guests and generate more enthusiasm for this event. “Black Players Honor Clint Thomas,” Michigan Chronicle [Detroit, MI, July 7, 1979: A3.

39 Tom Stultz, telephone interview with the author, May 10, 2024. One of Thomas’s duties at the Capitol was providing representatives with coffee.

40 Ibid.

41 Ken Tingley, “Black Stars’ Memories Fond,” Ashland (Ky.) Daily Independent, July 5, 1979: 15.

42 Craig Davidson, “‘Life on the Road’ for Black baseball teams not easy,” Louisville Defender, February 16, 1984: C10.

43 “Cooperstown honors Blacks,” Michigan Chronicle, September 21, 1985: 3.

44 “Clinton Cyrus ‘Clint Hawk’ Thomas,” Find a Grave, Accessed August 28, 2024, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/97792763/clinton-cyrus-thomas.

Full Name

Clinton Cyrus Thomas

Born

November 25, 1896 at Greenup, KY (USA)

Died

December 3, 1990 at Charleston, WV (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.