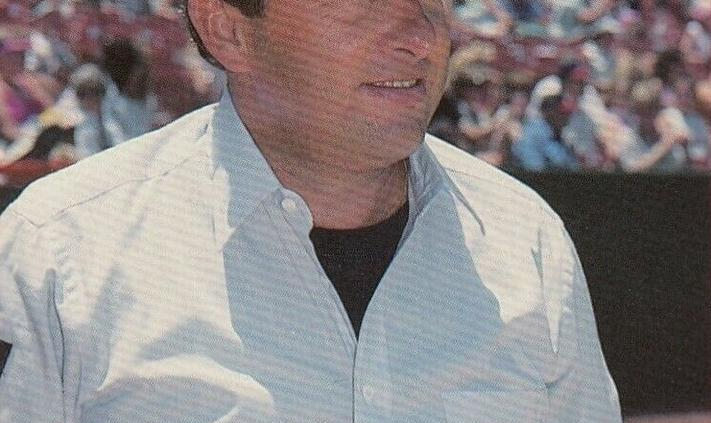

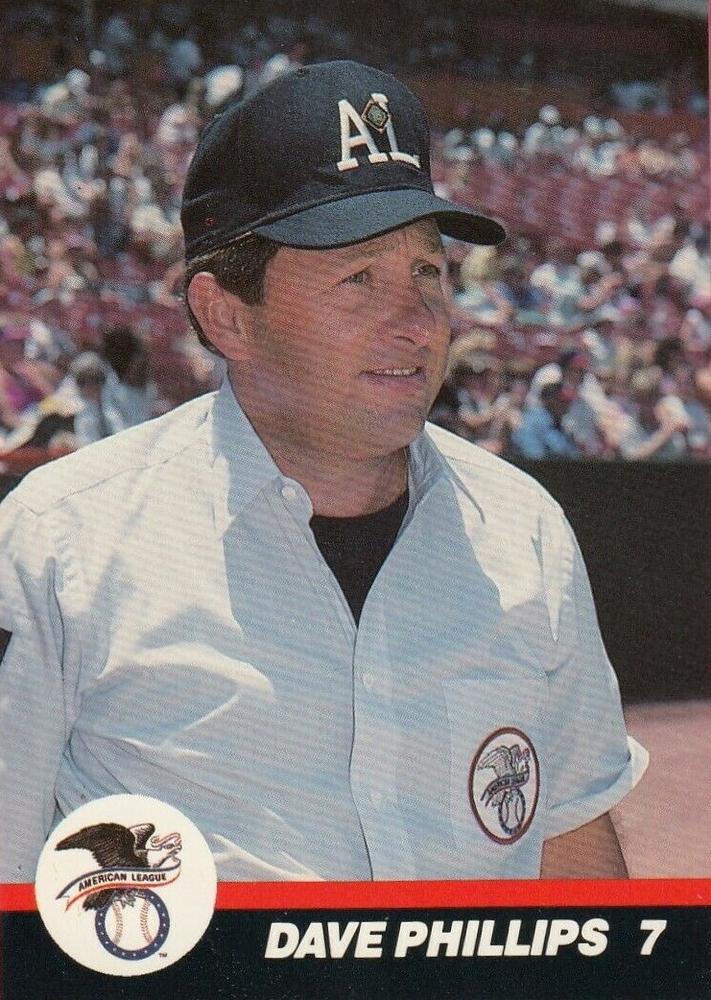

Dave Phillips

Developing a passion for umpiring began at a young age for Dave Phillips, and baseball was simply in his family’s DNA. His parents met on a St. Louis baseball field in the 1930s while his mother, Helen Creamer, was playing softball and his father, Bob Phillips, was umpiring her games. Their son grew up to become a respected major-league umpire for more than three decades, with World Series assignments, All-Star Games, and other well-known events on his resume.

Developing a passion for umpiring began at a young age for Dave Phillips, and baseball was simply in his family’s DNA. His parents met on a St. Louis baseball field in the 1930s while his mother, Helen Creamer, was playing softball and his father, Bob Phillips, was umpiring her games. Their son grew up to become a respected major-league umpire for more than three decades, with World Series assignments, All-Star Games, and other well-known events on his resume.

David Robert Phillips was born in St. Louis on October 8, 1943. By the time Dave was 3 years old, his father was umpiring games in the minor leagues. As a boy, he watched his father in action for 10 years. Bob Phillips’s umpiring career took him to the Carolina League, Piedmont League, Western League, and the American Association. Phillips’s father umpired games featuring many players who later served as managers during Dave’s big-league tenure, including Earl Weaver, Dick Williams, Bill Rigney, Chuck Tanner, Ralph Houk, Whitey Herzog, Don Zimmer, Bill Virdon, and Eddie Stanky.

Dave always enjoyed going to the dressing room after his father’s games, but he learned a valuable lesson when he questioned his dad one night, “Why did you throw out Earl Weaver?” With his father’s stern look and explanation, Dave learned very quickly not to ask an umpire those kinds of questions after a game.

Like most kids at 14, the young Phillips dreamed of becoming a big-league baseball player like his hometown hero, Stan Musial. He imagined hitting home runs, making diving catches and playing in the World Series. Phillips never thought of becoming an umpire until he started having trouble hitting the curveball. At about the same time, his baseball team was asked if they wanted to umpire YMCA Little League games. No one raised their hand until they were told that it would pay $5 per game. Then, the entire team raised their hands – that was more money than you could make mowing grass or delivering papers. Looking back, Phillips believes those early years of umpiring helped him gain confidence and taught him how to manage the game, which gave him an advantage when he attended umpiring school.

After attending college at Southeast Missouri State University, Phillips decided to attend the Al Somers Umpiring School in Daytona, Florida. His father was somewhat opposed to his son pursuing a career in umpiring, because he didn’t want Dave to experience the same heartache that he had when he didn’t reach the major leagues.

Phillips remembers driving his 1964 Pontiac, four-speed on the floor, from St. Louis to Daytona on a very cold January day in 1964. He was 20 years old and apprehensive as he walked into the school. There were 99 students, and only four of the 1964 class made the major leagues – Ron Luciano, Larry Barnett, Jake O’Donnell, and Phillips. O’Donnell quit after four seasons in the major leagues and became a legendary referee in the NBA. Luciano resigned after 11 seasons and became a best-selling author and an announcer for NBC. Barnett and Phillips umpired for 31 seasons apiece.1

After six weeks, Phillips (who stood 5-feet-11 and weighed 180 pounds) graduated at the top of his class and was selected to umpire in the Class A Midwest League. After two years, he was promoted to the Double A Texas League, and then after only one year, he was promoted to the Triple A International League. He spent only seven seasons in the minor leagues.

While in the Midwest League, he became good friends with Barnett. They were in each other’s weddings, and coincidentally married women named Sharon. On the last day of their second season, Barnett drove Phillips halfway from Burlington, Iowa to meet his father on the highway. Phillips had to hurry home to St. Louis for the birth of his first daughter in late August.

In the Texas League, Phillips worked with a legend, Frank “Frannie” Walsh. Phillips credited his father as his biggest mentor, but felt lucky to have worked with Walsh, who had umpired in the National League. “Frank had a fiery, aggressive umpiring style and was well respected, a great partner, teacher, mentor, and fantastic confidence builder,” Phillips recalled. Walsh was always promoting Phillips by telling everyone he met that Phillips “couldn’t miss at becoming a major-league umpire.”

Driving between the Texas League games with Walsh, there was never a dull moment. “Frank would scream at other drivers and get so angry at stoplights that he would get out of the car and yell at them to change,” remembered Phillips. The league had six teams spread between Arkansas and New Mexico, so the umpires spent a lot of time in the car. Phillips said he laughed so hard at Walsh’s humorous stories that he would have tears running down his face on a regular basis.

In 1967, at the age of 23, Phillips was promoted to the International League, where he spent four seasons. At that time, the league featured many veteran players aiming to get back to the major leagues when they expanded in 1969.2 The IL also featured future superstars, such as Johnny Bench, Nolan Ryan, Jim Palmer, Don Baylor, and Thurman Munson. In addition, several IL skippers went on to manage in the majors, including Weaver, Virdon, and Zimmer. The combination of older players and future stars made the IL feel like the major leagues, and Phillips said it was great experience for a young umpire.

When Phillips arrived in the IL, the combative Weaver was managing the Baltimore Orioles’ farm team in Rochester, New York. Years later, AL supervisor of umpires Dick Butler asked Phillips if there was anyone who had helped him during his career. Phillips quickly answered, “Yes, Earl Weaver.” Butler seemed shocked at his reply, and said, “How did Weaver help you?” Phillips explained, “I had so many arguments and ejections with Weaver that he helped me learn how to handle difficult personalities and negative situations that I would have to deal with during my career. Weaver was brutal in the minors. He had such a fiery temper that he would take a base from the field and lock himself in the locker room, and we would have to delay the game.”

In 1970, the American League purchased Phillips’s contract. He was asked to go to the Arizona Instructional League for two months to learn how to use the balloon-style outside chest protector, which he had never used, but would be required to use in the AL.

At age 26, he became one of the youngest umpires in the majors. He made his debut on April 6, 1971, umpiring at third base for a game between the Kansas City Royals and California Angels. As he walked into Anaheim Stadium to work his first game, Phillips thought to himself, “I always asked God to help me become an MLB umpire…at that moment I said to God, ‘Well, we made it. Thanks.’” This was the first of 3,933 regular-season major-league games for Phillips. Two days later, he worked his first game behind the plate. Phillips worked 173 games in his first season of umpiring in the major leagues.

After only seven seasons as an American League umpire, Phillips was selected as a crew chief, one of the youngest to reach that level. Other highlights of his career include working four World Series, including two as crew chief; nine playoff series; and two All- Star Games.3 He was also selected by the Commissioner’s office to umpire an exhibition series with the Royals in 1981 in Japan.

Throughout his career, Phillips’s umpiring earned praise from sportswriters, umpire polls, executives and other observers. In August 1973, veteran umpire Bill Haller called him “one of the best in the league now,” adding, “he has an unusual command of a game for his age. … and he knows how to take charge out there.”4

In 1980, baseball writer Peter Gammons of the Boston Globe ranked Phillips as the best umpire in the American League.5 Seven years later, writing for Sports Illustrated, Gammons polled major-league catchers on the best and worst arbiters. Phillips was voted as one of the five best in the American League.6

In 1982, Phillips was featured on PM Magazine, which aired on NBC. The show interviewed Billy Martin, another manager known for his fiery temper, who had high praise for Phillips’s umpiring ability and career. “He’s one of the best in baseball, without a doubt,” Martin said. “He’s fair and aggressive, and I admire him very much. It’s a tough job being an umpire.”

One of the most unusual games Phillips was assigned to umpire was the infamous “Disco Demolition Night.” Phillips led the umpiring crew in a scheduled doubleheader between the Detroit Tigers and Chicago White Sox on July 12, 1979, in Chicago’s Comiskey Park. A promotion encouraged fans to bring disco records that would be blown up on the field between games. Phillips came out to the field expecting to start the second game, only to find that thousands of fans had converged on the field, and center field was on fire. The playing field was so damaged and overrun that the White Sox had to forfeit the second game. To restore order, police dogs were brought onto the field, and Harry Caray, the White Sox announcer, urged calm over the public-address system.

Phillips was also the home-plate umpire on July 15, 1994, when White Sox manager Gene Lamont accused the Cleveland Indians’ Albert Belle of using a corked bat. Phillips examined the bat, and then had it taken to his locked dressing room for future inspection. During the game, Indians relief pitcher Jason Grimsley broke into the umpires’ dressing room. He climbed through the ceiling and dropped down into the room. Grimsley swapped Belle’s corked bat with a bat belonging to teammate Paul Sorrento.7

“After the game when we got to our dressing room, there were several baseball executives standing outside,” Phillips recalled. “They told me that the umpires’ room had been broken into and immediately asked if I thought I could identify the bat I had confiscated during the game. They had an extremely large picture of me examining the bat on the field. The bat in the umpires’ room was obviously a different bat from the bat that I confiscated.” After an intensive investigation by the head of major-league security, Kevin Hallinan, the Indians brought the original bat that Phillips had confiscated; it was x-rayed and found to be corked. Belle was suspended for seven days.8

Phillips was also responsible for two publicized ejections involving doctored baseballs. Hall of Famer Gaylord Perry was well-known for tampering with the baseball, going so far as to title his 1974 book Me and the Spitter. During Perry’s 22-season major-league career, Phillips was the only umpire to ever eject him for doctoring the ball, in a game between the Seattle Mariners and Boston Red Sox on August 23, 1982.9 Later, Perry appeared on Lie Detector, a TV show hosted by celebrity attorney F. Lee Bailey, and took a lie detector test.10

Five seasons later, on August 3, 1987, Phillips ejected the Minnesota Twins’ Joe Niekro from a game against the California Angels. After being checked, Niekro dropped a broken piece of emery board out of his back pocket. Phillips picked it up and said, “What is this?” Niekro said, “I use that sandpaper to file my nails between innings.” Phillips ejected him. Niekro appeared on Late Night with David Letterman about two weeks later and walked out with a carpenter’s belt on, carrying an electric sander, a manicure kit, and a tube of Vaseline. Asked by Letterman if he doctored the ball that night, Niekro replied to audience laughter, “Do I look like a doctor?”11

In total, Phillips ejected 88 players, coaches, and managers, including two ejections each for the famously argumentative Martin, Weaver, Williams, and Lou Piniella. His first ejection was Hall of Famer Reggie Jackson, who threw his helmet while arguing a call at second base in May 1971.

Phillips’s ejections of Weaver were something of a family tradition, as Bob Phillips had ejected Weaver in the minor leagues. “When I began umpiring in the International League, I found out why my dad one year had ejected Weaver many times,” Phillips said.

“The entire time I was in the major leagues, I never thought Earl Weaver knew that my dad had umpired in the minor leagues,” added Phillips. “Later, after I had retired, and was a part of a charity golf tournament with Weaver, I overheard him saying, ‘Dave’s dad threw me out of a lot of games.’ That’s the first time I was aware that he knew my dad. Weaver then explained that he knew who I was the first day I showed up in the International League.”

Although Phillips never umpired behind the plate for a no-hitter, he worked on the base paths for six of them, including no-nos thrown by Hall of Famers Ryan and Randy Johnson.12 He was behind home plate for the deciding Game Seven of the 1987 World Series, won by the Minnesota Twins, 4-2, over the St. Louis Cardinals.

One of the funniest incidents from Phillips’s career took place May 27, 1981, in a game between the Mariners and Kansas City. Amos Otis of the Royals hit a slow roller down the third base line, where Mariners third baseman Lenny Randle watched and waited. When the ball looked like it was going to stay fair, Randle got down on his hands and knees and started blowing on the baseball to push it foul. Home plate umpire Larry McCoy signaled “foul ball.” Royals manager Jim Frey came out to argue, and crew chief Phillips came in from third base to join the discussion. “Since there was not a rule in the book covering blowing the ball foul, I just used common sense and called Otis safe at first base because of Randle physically blowing the ball,” explained Phillips. “Obviously, the Kansas City Royals immediately agreed with me, and left. However, the Seattle manager, René Lachemann, came running out of the dugout screaming that Randle did not do anything wrong.” To try to prove his point, Lachemann asked Randle if he blew the ball foul. Randle brought laughter to the argument by saying, “No, Skip, I just yelled ‘GO FOUL, GO FOUL’ and it went foul.” Phillips’s call of a fair ball stood.

Phillips spent his final two seasons working for both the American and National Leagues after the two leagues merged their umpiring staffs. He umpired his last game on April 1, 2002, between the Cincinnati Reds and Chicago Cubs at Cincinnati’s Cinergy Field. In a measure of how much time Phillips had spent as an MLB umpire, four of the nine pitchers who appeared in his last game hadn’t been born in 1971 when Phillips umpired his first major-league game,13 and the Cubs’ manager that day, Baylor, had been a star International League outfielder with the Rochester Red Wings in 1970, Phillips’s last season working in that circuit.

Toward the end of Phillips’s career in June of 1999, several health issues kept him from umpiring. He herniated a disc in his lower back and, with regrets, had to step aside from working the plate in the All-Star Game in Fenway Park in which Ted Williams was honored.

Phillips missed the remaining part of the 1999 season and all of 2000 because of back surgery and intensive rehab. He returned in 2001 but worked only 74 games owing to injuries. He nursed a strained knee meniscus during spring training of 2002, then tore it in the eighth inning of the Opening Day game in Cincinnati. He was able to finish the game, limping badly. Phillips had surgery and rehabbed the rest of the year. After two years of intensive surgery rehab, on top of the wear and tear he had endured during his long career, he sadly decided to retire.

The toughest part of the job, Phillips said, was being away from home for half of the year. In 1964, Phillips married his high school sweetheart, Sharon Rouse, and they had three children – Kimberly, Jill, and Randy. Home was in Lake St. Louis, Missouri, a suburb about 40 miles west of St. Louis with two lakes. When Phillips had time off, he could be found in his backyard enjoying the lake with his family. During his extensive time away from home, Phillips relied heavily on Sharon to take care of raising the children and managing the house. “Sharon’s ability to juggle everything was a pivotal role in the success of my career,” he said. “Without her support, I would have never been able to work in my two careers.”

During the offseason, Phillips officiated major college basketball and was promoted to supervisor of officials for several major college basketball conferences. He spent a lot of time going to airports and living out of suitcases. One of his daughters remembers always thinking of him when she heard the song lyrics, “Leaving on a jet plane and I don’t know when I’ll be back again…”14 Before he left for the airport, Phillips would often leave encouraging notes on his children’s pillows. He traveled so much that his son told his friends that “my Daddy works at the airport.” Although Phillips didn’t always like spending so much time away from home, the job provided him with offseason income; when he became a supervisor of officials, he didn’t have to travel as much.

Over the years, the Phillips family grew to include eight grandchildren. As his children and grandchildren were growing up, Phillips always encouraged them to find something they loved, have a good work ethic, and give it 110% effort, the same work ethic he brought to his career as an umpire. During summers off from school, the kids took turns visiting their father on the road. When he was on the field during a game, Phillips had a sign to say hello to his family: He would tap his hat on the top. Baseball also gave the Phillips family many funny stories, including the time that one of his young daughters mistook a church organ for a ballpark organ, stood up on a pew, and yelled “Charge!”

After retiring, Phillips co-wrote the book Center Field on Fire – An Umpire’s Life with Pine Tar Bats, Spitballs, and Corked Personalities. The book highlights many of the historical, colorful, and controversial events that Phillips witnessed during his decades in baseball. In the book’s foreword, broadcaster Bob Costas described Phillips as “a first-rate baseball citizen, one of the best in his profession, and an umpire who always believed that the players should be the stars.” “He took that job very seriously, and honestly felt privileged to do it,” Costas wrote. “His love for the game showed every day, not only among his peers, but also with the players and managers with whom he shared the field. He was always enthusiastic, upbeat, accessible, and helpful to writers, and always genuinely concerned with the best interests of the game of baseball.”

In his book, Phillips said many baseball fans believe that being a major league umpire is a pretty good job. Fans see umpires work about three hours a day umpiring a game and hear that they travel first class all over the country, watch great athletes close up, and receive five months of vacation in the winter. In reality, Phillips explained, “you are making calls that one team and thousands of fans are going to disagree with each time. Being an umpire is not a popularity contest – you must know how to handle people and control situations. Credibility is the name of the game for the umpire.” He said the major-league umpires’ six-week strike in 1979 went a long way toward giving umpires the credibility and respect that they deserved. “The veteran umpires earned that credibility, and the men hired to replace the umpires did not have it. They found out quickly that not just anyone can do this job – and the strike was settled.”

As this bio began, it will end – being an umpire was simply in Dave Phillips’ DNA. In many ways, he felt more at home on a baseball diamond than anywhere else all his life. According to Phillips, one of the highlights of his career was having his mom and dad attend two of the World Series he worked – in 1976 between the New York Yankees and the Cincinnati Reds, and in 1982 between his hometown St. Louis Cardinals and the Milwaukee Brewers. A few months after the 1982 World Series, his father passed away suddenly. His mother, Helen, died in 2005. For a couple who met on a baseball field, their son absolutely lived out their “field of dreams.”

In 2004, Phillips was inducted into the Missouri Sports Hall of Fame, the first umpire to receive this honor.15 When asked about his long and distinguished career, Phillips said, “A lot of people go through life and never find a job they really like, but I not only found a job I liked, but a profession that I truly loved.”

Author’s note

The author of this biography is Dave Phillips’s daughter.

Unless otherwise cited, the article is based on firsthand discussions with Phillips about his career, as well as his book, Center Field on Fire – An Umpire’s Life with Pine Tar Bats, Spitballs, and Corked Personalities (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2004).

Acknowledgments

This story was reviewed by Kurt Blumenau and Rory Costello and checked for accuracy by SABR’s fact-checking team.

Notes

1 As will be mentioned later in this biography, Phillips missed the entire 2000 season with an injury. He would have umpired for 32 seasons had he been healthy in 2000.

2 Some of the veterans who Phillips recalls from his seasons in the IL include Ernie Broglio, Bill Tuttle, Sam Jones, Gene Stephens, Chuck Estrada, and Tommie Aaron.

3 Phillips was chosen to umpire the World Series in 1976, 1982, 1987 and 1993; the AL Championship Series in 1974, 1978, 1983, 1985, 1989, and 1995; the AL Division Series in 1981, 1997 and 1998; and the All-Star Game in 1977 and 1990.

4 Sandy Padwe, “4 Umpires Turn the Tables, Call a Few On Themselves,” Newsday (Long Island, New York), August 19, 1973: Sports: 1.

5 Peter Gammons, “Rating Them … 1, 2, 3,” Boston Globe, September 19, 1980: 42. “In most cases, these items have been debated with managers, players, and coaches,” Gammons noted.

6 Peter Gammons, “Whatever Happened to the Strike Zone?” Sports Illustrated, April 6, 1987. https://vault.si.com/vault/1987/04/06/what-ever-happened-to-the-strike-zone.

7 Joseph Wancho, “July 15, 1994: Albert Belle’s Corked Bat Leads to Suspension,” SABR Games Project, accessed December 2023. https://sabr.org/gamesproj/game/july-15-1994-albert-belles-corked-bat-leads-to-suspension/.

8 Wancho.

9 Perry was ejected from two other games for other reasons. On April 23, 1970, ump Chris Pelekoudas ejected Perry from a San Francisco Giants-Houston Astros game for arguing a balk call from the bench. And on July 24, 1983, in the Kansas City Royals-New York Yankees “Pine Tar Game,” umpire Tim McClelland ejected Perry for trying to smuggle George Brett’s pine tar-smeared bat into the Royals clubhouse.

10 The episode aired in January 1983. According to news reports, Perry passed the lie detector test. “Lie Detector” (advertisement), Los Angeles Times, January 24, 1983: VI:8; United Press International, “Gaylord Perry ‘Passes’ a Lie Detector Test,” Brattleboro (Vermont) Reformer, October 30, 1982: 20; Paul Hagen, “Perry Just Keeps on Pitching,” Fort Worth (Texas) Star-Telegram, March 18, 1983: 2B.

11 As of September 2024, a recording of Niekro’s appearance was available on YouTube at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cGEMk-YKWLA; Dan Barreiro, “Niekro Flaunts Scuff Ball Issue,” The Town Talk (Alexandria-Pineville, Louisiana), August 16, 1987: B7.

12 In order, Phillips worked Ryan’s no-hitter for California against Detroit on July 15, 1973; Jim Bibby’s no-hitter for the Texas Rangers against the Oakland A’s two weeks later on July 30, 1973; the no-hitter thrown by four Oakland pitchers against California on the final day of the regular season, September 28, 1975; Johnson’s no-hitter for the Seattle Mariners against Detroit on June 2, 1990; Bret Saberhagen’s no-no for the Kansas City Royals against the Chicago White Sox on August 26, 1991; and Scott Erickson’s no-hitter for the Minnesota Twins against the Milwaukee Brewers on April 27, 1994. Phillips worked at first base for all games except Johnson’s and Saberhagen’s, where he was stationed at second base.

13 The pitchers, and their birthdates, were the Cubs’ Kyle Farnsworth (April 14, 1976) and the Reds’ Scott Williamson (February 17, 1976), Gabe White (November 20, 1971), and Danny Graves (August 7, 1973). Another Cincinnati pitcher that day, Scott Sullivan, was born on March 13, 1971, and was less than a month old at the time of Phillips’s big-league debut.

14 From the song “Leaving on a Jet Plane,” written by John Denver, a U.S. number one hit in 1969 for Peter, Paul, and Mary.

15 Phillips has also been inducted into the St. Louis Sports Hall of Fame. St. Louis Sports Hall of Fame website, accessed December 2023. https://www.stlshof.com/dave-phillips-2/.

Full Name

David Robert Phillips

Born

October 8, 1943 at St. Louis, MO (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.