Jim Marshall

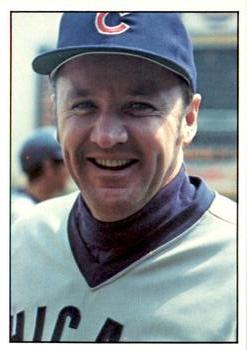

Despite having an impressive minor-league record, left-handed-hitting Jim Marshall never could crack the starting lineup on a regular basis for five major-league clubs. As a result, he served mostly as a backup first baseman/outfielder and pinch-hitter during a major-league career that started in 1958 and ended in 1962. After his playing days he became a manager, most notably piloting the Cubs in the mid-1970s.

Despite having an impressive minor-league record, left-handed-hitting Jim Marshall never could crack the starting lineup on a regular basis for five major-league clubs. As a result, he served mostly as a backup first baseman/outfielder and pinch-hitter during a major-league career that started in 1958 and ended in 1962. After his playing days he became a manager, most notably piloting the Cubs in the mid-1970s.

Rufus James Marshall was born on May 25, 1931, in Danville, Illinois, the son of Rufe and Frances Marshall. Jim and his parents moved to Compton, California, when he was a youngster. The elder Marshall graduated from the University of Illinois where he played baseball, football, and basketball. He umpired for several years in the Three-I League while heading the athletic program at Havana High School in Havana, Illinois, and later in the Pacific Coast League after the family moved to California. He was also a teacher and multi-sport coach at the junior high and high school levels in Southern California.1

In February 1948 the younger Marshall, known as Jim, was named to the Beverly Hills All-Tournament Basketball Team as a six-foot guard.2 In January 1949 he scored 11 points and sank the game-winning free throw in Compton High School’s 36-35 overtime win over Grossmont High School.3 He was one of 10 players on the all-conference basketball team two months later.4 In fact, UCLA basketball coach John Wooden tried to recruit Marshall when Marshall was 18 years old.5 “That was when he [Wooden] was just getting his program going out there,” Marshall recalled years later. “The reason he wanted me was probably because I was left-handed; he always seemed to want at least one guy who could go the other way.”6 An “A” student, he earned 13 letters at Compton High School—graduating in June 1949—and attended Compton Junior College for one year during the offseason.7

Nearly every major-league baseball team was interested in Marshall during the summer of 1949.8 Marshall went 6-for-9 with one home run, one double, four singles, and six intentional passes in four games featuring conference all-stars at Gilmore Field in Long Beach, California.9 He also drove in four runs and stole four bases. On August 6, 1949, Marshall and his father met Brooklyn Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey and former major leaguer George Sisler at a baseball coaches’ school in San Louis Obispo, California.10 A day later, father and son talked to Oakland Oaks owner-president Brick Laws and investigated the possibility of attending Stanford University on an athletic scholarship to pursue a pre-med or physical education major.11

Marshall was selected to participate in the fourth annual Hearst Sandlot Classic at the Polo Grounds in New York City on August 18, 1949. “Marshall was chosen for the trip East for his speed, batting power, throwing and all-around baseball savvy,” wrote sportswriter Bob Hall.12 The annual contest pitted all-stars chosen by Hearst papers in 12 cities against all-stars picked by the New York Journal-American. The U.S. all-stars managed by Oscar Vitt overcame a five-run deficit and beat the New York team guided by Rabbit Maranville, 7-6.

After the game in New York, Marshall and his parents were guests of Boston Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey for three days and were hosted by the St. Louis Browns for several days starting September 2. In previewing the swing through the East, the Long Beach Press-Telegram noted that Marshall “has already turned a cold shoulder to some rather sizeable bonus offers.”13

On June 6, 1950, Marshall signed a contract for an undisclosed amount with the Oakland Oaks in the Pacific Coast League. Three weeks later, sports editor Alan Ward explained how the signing unfolded.14 A year earlier, Oaks manager Chuck Dressen noticed Marshall at an informal workout in Hollywood, California, and told Laws about him. Then Laws, who knew Rufe Marshall, began to follow Jim. At one point, Laws even predicted that Marshall would probably become a bigger name in baseball than Oakland natives Jackie Jensen or Billy Martin.15

Marshall’s father did not want his son to sign a bonus contract, which could have limited his playing time. “Rufe figured that Jim would make the grade more rapidly, and with greater permanence, if he could play regularly,” Ward wrote.16 Laws agreed, saying, “Jim will go further and make more money in the long run if he keeps out of the bonus category.”17 After signing with Oakland, Marshall was farmed out to the Albuquerque Dukes in the Class C West Texas-New Mexico League.

The 19-year-old first baseman had an immediate impact. On June 23 Marshall hit two “tremendous blasts” over the right-center field fence and a “wicked three-bagger” in the Dukes’ 26-8 rout of the Amarillo Blue Sox.18 “The kid is playing first base with the aplomb of Hal Chase,” Albuquerque manager Herschel Martin said. “He looks like a player with five years’ experience.”19 On July 7 in Clovis, New Mexico, Marshall slugged a grand slam homer and drove in five runs in the Dukes’ come-from-behind 15-5 victory. Four days later, his parents saw him hit his ninth home run of the year and a triple in an 8-0 win over Borger. In late July sports editor J.D. Kaiser picked Marshall for the first base position in the league’s fourth annual North-South All-Star Game in Pampa, Texas. “Marshall has shown brilliant power hitting in the clutch and has few peers as a fielder,” Kaiser said.20

In his first season as a pro, Marshall hit .336 with 19 doubles, a league-leading 17 triples, 15 home runs, and a .631 slugging percentage. The Dukes finished second with an 89-58 record, then beat the Lamesa Lobos four games to one for the West Texas-New Mexico League championship.

In 1951 Marshall was promoted from Class C all the way to Triple-A when he opened the season with the Oakland Oaks. He started out fast, belting nine home runs in the first month, but triple-A pitchers adjusted to him and he soon slumped to .235. On June 1 he was optioned to the Wenatchee (Washington) Chiefs in the Class B Western International League.21 Marshall hit .261 with 11 homers and 62 RBIs for the Chiefs, and after their season ended, he was recalled to the Oaks, but finished his triple-A season at .225.

In the fall of 1951 Marshall married Beverly Ann Dodds, whom he had met in junior high school.22 The couple had three children: son Blake, born in 1955, who attended Arizona State University; son Craig, born in 1957, who attended Northern Arizona University; and daughter Alison, born in 1960, who attended Pepperdine University. The Marshalls were married for 64 years before Beverly’s death on February 29, 2016, in Arizona.23

Marshall went to spring training with the Oaks in 1952, but on March 25 he was optioned to Nashville in the double-A Southern Association. The move from Class B to Double-A was a big step in the right direction for young Marshall.24 He appeared in 154 games and proved he could handle double-A competition, batting .296 with 24 homers and 98 RBIs. In addition, he helped Nashville set a Southern Association record 222 double plays in one season.25

In 1953 Marshall finally stuck with Oakland. In fact, he spent the next three years with the unaffiliated Oaks. Years later, Marshall looked back fondly at his time in the Pacific Coast League. “That was a very prestigious league in those days, with teams like the San Diego Padres and Hollywood Stars and going all the way up the coast to Seattle,” he said. “At the time, if your home was the West Coast, it was wonderful to be in the PCL.”26

Marshall became the regular first baseman for the 1953 Oaks, appearing in 151 games and batting .273 with 24 homers and 99 RBIs. In 1954, he hit .285 and led the PCL with 31 homers and 123 RBIs in 166 games. After the season, the Oaks cashed in on their investment in Marshall, selling him and pitcher Don Ferrarese to the White Sox in October for a reported $50,000.27

Marshall’s White Sox era started shakily when manager Marty Marion spoke of moving the career first baseman to the outfield for 1955.28 At spring training in Tampa, Marshall got in very little work, as the Sox decided to use slugger Walt Dropo at first base. By April, Marshall was back in Oakland on option from the White Sox.29 He hit 30 homers in 169 games for the Oaks but his batting average was a disappointing .240.

In 1956 Marshall again went to spring training with the White Sox. As the team worked its way north in April to start the season, the Sox played the Cardinals in an exhibition game in Memphis, after which Marshall and two others were dropped off to spend the season with the Chicks in the double-A Southern Association.30 Marshall collected 28 homers and 106 RBIs in 147 games for Memphis. History repeated itself in 1957. After spending the spring with the White Sox in Tampa, Marshall was optioned again in early April, this time back to the PCL to play for the Vancouver Mounties.31 He played well, batting .284, popping 30 home runs, and knocking in 102. He also had a PCL-leading 188 hits in 168 games for Vancouver.

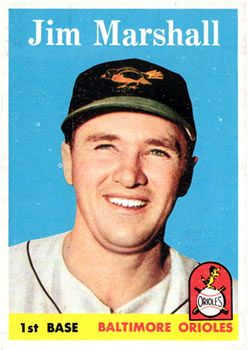

In December 1957 the Chicago White Sox traded Marshall, outfielder Larry Doby, and pitchers Russ Heman and Jack Harshman to the Baltimore Orioles for pitcher Ray Moore, infielder Billy Goodman, and outfielder Tito Francona. After Marshall went 4-for-4 in the Orioles’ 8-4 win over the Chicago Cubs at the end of spring training in 1958, Baltimore manager Paul Richards said, “I want to see a lot more of that boy. He can run, throw and field. Now, if he can continue to supply this kind of hitting, how are we going to keep him out of a job?”32 Marshall was in the Orioles starting lineup for Opening Day, playing first base and batting fourth. He had two singles and scored a run in his major-league debut. On May 1 he hit his first home run, a solo shot off Jim Wilson in a 4-3 loss at home to his former team, the White Sox.

Despite playing flawlessly in the field, Marshall tailed off at the plate and was hitting only .215 when the Orioles sold the first baseman-outfielder to the Chicago Cubs on August 23, 1958. The move was made to create room on the roster to acquire pitcher Hoyt Wilhelm, whom Baltimore obtained from Cleveland for the $20,000 waiver price. Although Wilhelm had a 2-7 record, he sported a 2.49 earned run average, fourth best in the American League at the time. “Marshall was unhappy in this [pinch-hitting] role, although he never complained,” wrote sportswriter Lou Hatter. “His defensive credentials certainly showed above average during his brief Oriole career.”33

Despite playing flawlessly in the field, Marshall tailed off at the plate and was hitting only .215 when the Orioles sold the first baseman-outfielder to the Chicago Cubs on August 23, 1958. The move was made to create room on the roster to acquire pitcher Hoyt Wilhelm, whom Baltimore obtained from Cleveland for the $20,000 waiver price. Although Wilhelm had a 2-7 record, he sported a 2.49 earned run average, fourth best in the American League at the time. “Marshall was unhappy in this [pinch-hitting] role, although he never complained,” wrote sportswriter Lou Hatter. “His defensive credentials certainly showed above average during his brief Oriole career.”33

When he walked into the Cubs’ locker room the next day, manager Bob Scheffing asked Marshall, “Are you ready to play?” “Yes, sir,” Marshall responded.34 The Cubs’ newest player proved he was ready by collecting three home runs and two singles in a doubleheader loss to the Philadelphia Phillies at Wrigley Field on August 24. “At Baltimore,” Marshall said, “I was just a sub. I went in to pinch hit once in a while, but seldom had the opportunity to play regularly. The sweetest words I’ve ever heard were by Scheffing today when he asked me if I was ready to play.”35

Marshall also pointed out that he played at Wrigley Field in Los Angeles during his time in the Pacific Coast League. “I always had good luck at Wrigley Field in Los Angeles. When I was told I had been traded to the Cubs, I hoped I’d have good luck at Wrigley Field in Chicago,” he said. “It worked, and I only hope I can keep it up.”36 His new manager had seen him play in the Pacific Coast League too while managing the Los Angeles Angels. “He has good power and a lot of speed,” Scheffing said. “And the great thing about getting him is the fact that we didn’t have to give up any players.”37

In 1959 Marshall posted major-league career highs in home runs (11) and RBIs (40) in just 294 at-bats, while hitting .252 and making only two errors at first base and in the outfield. Despite having the best year of his major-league career, the Cubs traded Marshall and pitcher Dave Hillman to the Boston Red Sox for first baseman Dick Gernert on November 21, 1959.

On March 16, 1960, the Red Sox traded Marshall and catcher Sammy White to the Cleveland Indians for catcher Russ Nixon. White refused to report to the Indians nine days later, and Commissioner Ford Frick voided the deal upon White’s retirement from baseball. Four days later, the Red Sox sent Marshall to the San Francisco Giants for pitcher Al Worthington.

On the night of March 29, Beverly Marshall gave birth to the couple’s daughter, Alison Ann, at a Compton hospital. When told about the trade to San Francisco the next morning, Marshall said, “I know I can help the club. I brought along both my bat and my glove.”38

When Willie McCovey was demoted to Triple-A Tacoma in July 1960, Marshall took over first base against right-handed pitching. “He [Marshall] has been fighting desperately to hold the job, putting on an exhibition that has been positively inspiring,” sports editor Curley Grieve wrote. “He tries to climb the concrete walls to get foul balls, he roars down to first even when he’s out 20 feet, he rips into bases on close plays, he stands commandingly at the plate daring pitchers to move him back.”39 McCovey, the National League’s Rookie of the Year in 1959, was recalled two weeks later, but was slated for pinch-hitting duty at first. “[Manager] Tom Sheehan isn’t going to take Jim Marshall out of the lineup the way he has been batting and fielding,” sportswriter Walter Judge said. “Jim’s play has given the club a needed lift.”40 However, in the end, Marshall finished the 1960 season with only 136 plate appearances in 75 games, and a .237 average.

After the season Marshall accompanied the Giants on a 16-game goodwill tour of Japan. He helped 20-year-old Sadaharu Oh improve his footwork around the first base bag during the tour that ended with a 3-2 loss to the Japanese All-Stars in Shizuoka.

Marshall got into the lineup for the first time the next season in the Giants’ 6-5 win in 12 innings over the Pirates on April 13. Marshall replaced McCovey at first late in the game and made a game-saving catch and throw in the ninth. “The classy Marshall … plunged headlong to his left, rolled over, and came up throwing easily to [pitcher Jack] Sanford for the game-saving out,” the San Francisco Examiner reported.41 Marshall had a philosophical approach to his role as a pinch-hitter. “We’ve got a job to do on the bench. We can’t just sit and think of ourselves,” he said. “We’ve got to think about everybody else. If you do that, you’re helping the club. And that’s what counts.”42

On May 17 Marshall’s walk with the bases loaded accounted for the Giants’ winning run in a come-from-behind 4-3 win over the Chicago Cubs at Candlestick Park. Batting for pitcher Stu Miller in the ninth, Marshall took four straight balls from Cub reliever Don Elston to force in the winning run. The victory was the Giants’ 16th in 21 games.43

Marshall ended up back on the East Coast when the Giants sold him to the fledgling New York Mets on October 13, 1961. “This fella wasn’t getting anywhere playing behind Orlando] Cepeda and that other fella—McCovey,” Mets manager Casey Stengel said. “He’ll have an opportunity with us. It should make a better ballplayer of him.”44

Marshall pinch-hit and walked in the ninth inning of the first game the Mets ever played. He replaced the injured Gil Hodges at first base in the Mets’ home opener against the Pirates at the Polo Grounds on Friday, April 13, 1962. He went 1-for-3 with a walk and a double. The next day Marshall homered off Pittsburgh reliever Roy Face in a 6-2 loss. The day after that, Marshall homered again, off Pittsburgh starter Bob Friend in the Mets’ 7-2 loss in the first game of a doubleheader. In his brief time with New York’s new National League club, Marshall hit .344 and slugged .656, with three homers and four RBIs.

On May 6 the Mets traded Marshall to the Pirates for pitcher Vinegar Bend Mizell in an effort to bolster their pitching. Although Pirate fans were “somewhat indifferent” about the swap, sports editor Al Abrams pointed out that the ballclub was “woefully weak” in left-handed hitting on the bench.45 “Marshall, much traveled, experienced and who upon occasion packs power in his bat, could fill the void,” Abrams wrote. “Besides, he can play both first base and in the outfield.”46

Marshall made his first start for the Pirates at first base in place of the slumping Dick Stuart on May 11 at Cincinnati. He went 2-for-3 at the plate, but the Pirates lost, 3-2, in 10 innings.

Marshall hit his first home run for the Pirates—a three-run blast off Bob Purkey—in the team’s 6-4 loss to the Reds two days later. Playing in place of Dick Stuart again, Marshall clubbed his fifth home run of the year in a 6-4 defeat at the hands of the Reds on July 24. It would be the 29th and final home run of his major-league career. He finished his last year in the major leagues with five homers, 16 RBIs, and a .250 batting average in 72 games.

On October 15, 1962, the Pirates announced they had given Marshall his outright release so he could play overseas. In 1963 he was among the first wave of big leaguers to play in Japan when he signed with the Chunichi Dragons in Nagoya, Japan, about 235 miles west of Tokyo. Although he did not speak Japanese, the team provided an interpreter who sometimes told him, “You don’t want to hear that.”47 Marshall’s wife and children lived in Tokyo so the kids could attend American schools. “Each year, my goal was to beat Sadaharu Oh in a home run derby, but I could never do it,” Marshall said in an interview in 2023.48 Marshall said the Japanese teams, which were “very serious” and “very dedicated,” practiced a lot and focused on fundamentals.49 Although Marshall had a fairly successful three-year stint in Japan (.268 with 78 home runs), he missed his family. “My family wasn’t there [in Nagoya], and I think I was the only person who spoke English in Nagoya, and it finally got to me,” he told the Chicago Tribune in 1975.50

When his children were preparing to start high school, he and his family moved back to the U.S. Marshall then looked for a way to get back into baseball after a year off. “I’d always kind of thought about managing,” he said. “I spent a lot of time on the bench, and I used it to study the various managers I played for.”51 Marshall agreed to start at the bottom after attending a Cubs-Dodgers game in Los Angeles with Beverly and Cubs general manager John Holland.

At Lodi, California, in 1968, Marshall was the players’ “counselor in all things, from money problems to insurance problems to marriage problems.”52 He was also receiving $7,000 a year to manage at the lowest level compared to his Japanese salary of $40,000 plus a year. To survive the bus rides and $3-a-day meal money, he used some of the money he had saved while playing overseas. He managed the Cubs’ Class AA affiliate in San Antonio, Texas, the next two seasons and led the Missions to a third-place finish in 1970. He moved up to Class AAA in 1971 and led the Tacoma Cubs to the northern division title in the Pacific Coast League. In 1972 he guided the Wichita Aeros to the northern division title in the American Association and was named manager of the year. A year later, the Aeros finished second under Marshall’s guidance.

Marshall started the 1974 season as the third base coach for the big club in Chicago. On July 24, 1974, he succeeded Whitey Lockman as manager, and Lockman returned to his position in the front office as vice president and director of player development. Ernie Banks, one of Marshall’s teammates on the 1958 and 1959 Cubs, was on the coaching staff at the time. “Ernie hadn’t changed on the surface from when I played with him,” Marshall said in 2019. “He still said the same things. He made you feel comfortable.”53 The Cubs finished sixth (last) in the Eastern Division of the National League with a record of 66-96 that year. Marshall alone had a 25-44 record.

Under Marshall the Cubs tied for fifth place in 1975 with a record of 75-87. “With what we had, Jim Marshall was all right. I always like Jim. He’s a good friend,” said pitcher Darold Knowles. “You wouldn’t say he was a great manager, but he wasn’t a bad manager, either. We didn’t have a great club, and he did as good as he could with it.”54 In 1976 the Cubs had the same won-loss record and finished fourth in the Eastern Division. Based on run differentials, the 1975-76 Cubs won 12 more games than the Pythagorean formula predicted.

The emergence of third baseman Bill Madlock and pitcher Bruce Sutter was the highlight of Marshall’s tenure as manager, author Peter Golenbock claimed.55 Madlock won NL batting titles in 1975 and 1976. Sutter threw a split-fingered fastball and “became one of the great relievers in the history of the game.”56 Neither lasted more than five years, however, with the Cubs.57

The emergence of third baseman Bill Madlock and pitcher Bruce Sutter was the highlight of Marshall’s tenure as manager, author Peter Golenbock claimed.55 Madlock won NL batting titles in 1975 and 1976. Sutter threw a split-fingered fastball and “became one of the great relievers in the history of the game.”56 Neither lasted more than five years, however, with the Cubs.57

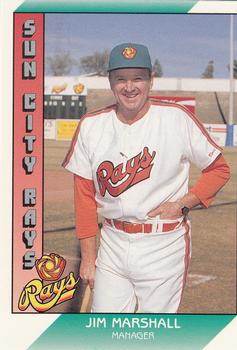

In mid-November 1976 Cubs president Philip K. Wrigley said he was satisfied with Marshall and would keep him as manager “if there are no objections.” Apparently there were objections, as Marshall was fired the next week.58 Marshall joined the Montreal Expos organization and managed the Denver Bears to the American Association championship in 1977. He guided the Vancouver Canadians, an Oakland affiliate, to a third-place finish in the Western Division of the PCL the next season. He returned to the major leagues as manager of the Oakland A’s in 1979. The A’s had a 54-108 mark under Marshall. “The team was a disaster as the [Charles] Finley ownership was on its last legs,” he recalled.59 He managed the Nashville Sounds—a New York Yankees affiliate—to a first-place finish in the Western Division of the Southern League in 1984. Two years later, he guided the Buffalo Bisons—a Chicago White Sox affiliate—to a second-place finish in the Eastern Division of the American Association. In 1990-1991, his Sun City Rays finished second in the Arizona Senior League.

Living full-time in Arizona, Marshall became one of the Arizona Diamondbacks’ original employees in 1996 and helped them prepared for the expansion draft. He served as a spring training instructor and then as Director of Pacific Rim Operations for 12 seasons from 1996-2007. before transitioning to a Senior Advisor role for his final 14 seasons with the club until he retired at the age of 90 in 2021. He continued to maintain relations with baseball organizations in Australia, Japan, Korea, and Taiwan.

In an interview in July 2023, Marshall said he was very happy and satisfied with his baseball career.60 Marshall’s personality was “easygoing, good-humored, and self-effacing,” interviewer Steve Treder said.61

Marshall died at the age of 94 on September 7, 2025.

Acknowledgments

This story was reviewed by Gregory H. Wolf and Rick Zucker and fact-checked by Dan Schoenholz.

Photo credits: Trading Card Database.

Sources

In addition to the sources listed below, the author used baseball-reference.com, paperofrecord.com, and the 1975 Chicago Cubs Official Roster Book.

Notes

1 “Young’s Yarns,” Bloomington (Illinois) Pantagraph, November 1, 1940: 14.

2 “Tarbabes Nudge Alhambra, 36-35; Cinch Tourney,” Long Beach Press-Telegram, February 29, 1948: 24.

3 “Tarbabes in Close Shave,” Long Beach Press-Telegram, January 15, 1949: 9.

4 “Name All-CIF Cage Team,” Long Beach Independent, March 22, 1949: 15.

5 Eddie Gold and Art Ahrens, The New Era Cubs 1941-1985 (Chicago: Bonus Books, 1985), 191.

6 Robert Markus, “The Making of a Manager,” Chicago Tribune, March 16, 1975: 233.

7 Bob Law, “Acorns Pick Off Prize Prospect; Wakefield Starts,” Berkeley (California) Gazette, June 6, 1950: 16.

8 Bob Hall, “Long Beach Clubs After Compton Diamond Star,” Long Beach Press-Telegram, August 9, 1949: A-13.

9 Hall, “Long Beach Clubs After Compton Diamond Star.”

10 Hall, “Long Beach Clubs After Compton Diamond Star.”

11 Hall, “Long Beach Clubs After Compton Diamond Star.”

12 Hall, “Long Beach Clubs After Compton Diamond Star.”

13 Hall, “Long Beach Clubs After Compton Diamond Star.”

14 Alan Ward, “On Second Thought,” Oakland Tribune, June 30, 1950: 30.

15 Alan Ward, “On Second Thought.”

16 Ward, “On Second Thought.”

17 Emmons Byrne, “The Bullpen,” Oakland Tribune, July 18, 1950: 35.

18 “Dukes Murder Blue Sox, 26-8,” Albuquerque Journal, June 24, 1950: 12.

19 Ward, “On Second Thought.”

20 J.D. Kaiser, “Scoreboard,” Albuquerque Journal, July 28, 1950: 22.

21 Bob Law, “Acorns Farm Marshall to Wenatchee,” Berkeley Gazette, June 1, 1951: 12.

22 “Miss Dobbs to Wed Jim Marshall in Fall,” Lynwood (California) Press, July 6, 1951: 14.

23 Jim Marshall, interviewed by Steve Treder via telephone, July 27, 2023 (“Treder interview”).

24 “Acorns Farm Jim Marshall to Nashville,” Oakland Tribune, March 25, 1952: 26.

25 Russ Melvin, “Vols Set DP Record With 222,” Nashville Tennessean, September 8, 1952: 12.

26 Markus, “The making of a manager.”

27 “White Sox buy Ferrarese, Marshall; Westlake to Phils,” San Francisco Examiner, October 17, 1954: 45.

28 “Marshall Will Get Crack at Outfield Spot,” Oakland Tribune, January 28, 1955: 39.

29 Jim Scott, “Scott’s Sport Shop,” Berkeley Daily Gazette, April 4, 1955: 14.

30 Will Carruthers, “First Baseman Jim Marshall Acquired by Chicks,” Memphis Press-Scimitar, April 9, 1956: 22.

31 David Condon, “Sox Head Home with Hopes of Big Surprise!,” Chicago Tribune, April 6, 1957: 38.

32 Jim Ellis, “‘Throw-In’ Rookie Marshall Bids for Bird Gateway Nod,” The Sporting News, April 16, 1958: 22.

33 Lou Hatter, “Orioles Buy Hoyt Wilhelm,” Baltimore Sun, August 24, 1958: 37.

34 Associated Press, “Marshall Makes Good with Bang,” Baltimore Evening Sun, August 25, 1958: 22.

35 Associated Press, “Marshall Makes Good with Bang.”

36 Associated Press, “Marshall Makes Good with Bang.”

37 Associated Press, “Marshall Makes Good with Bang.”

38 Walter Judge, “Giants Get Jim Marshall,” San Francisco Examiner, March 30, 1960: 57.

39 Curley Grieve, “Sports Parade,” San Francisco Examiner, July 31, 1960: 44.

40 Walter Judge, “Roadblock, Mac 2 Happy Fellows,” San Francisco Examiner, August 2, 1960: 46.

41 “Kuenn’s Single in 12th Gives Giants 6-5 Win Over Pirates,” San Francisco Examiner, April 14, 1961: 51.

42 Curley Grieve, “‘All Heroes’ to Dark,” San Francisco Examiner, April 14, 1961: 51.

43 https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1961/B05170SFN1961.htm, accessed October 8, 2023.

44 “Straight Talk from Casey,” San Francisco Examiner, October 17, 1961: 53.

45 Al Abrams, “Sidelights on Sports,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, May 8, 1962: 19.

46 Abrams, “Sidelights on Sports.”

47 Jim Marshall, Treder interview.

48 “Keeping Score,” Vineline.

49 Jim Marshall, Treder interview.

50 Markus, “The making of a manager,” 234.

51 Markus, “The making of a manager,” 234.

52 Markus, “The making of a manager,” 234.

53 Doug Wilson, Let’s Play Two: The Life and Times of Ernie Banks (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman and Littlefield, 2019), 167.

54 Peter Golenbock, Wrigleyville: A Magical History Tour of the Chicago Cubs (New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 1999), 433.

55 Golenbock, Wrigleyville: A Magical History Tour of the Chicago Cubs, 431.

56 Golenbock, Wrigleyville: A Magical History Tour of the Chicago Cubs.

57 Madlock played with the Cubs in 1974, 1975, and 1976. On February 11, 1977, he and Rob Sperring were traded to the Giants for Bobby Murcer, Steve Ontiveros, and Andrew Muhlstock. Sutter played for the Cubs from 1976 to 1980. On December 2, 1980, he was traded to the Cardinals for Leon Durham, Ken Reitz, and a player to be named later (Ty Waller).

58 Bob Verdi and Richard Dozer, “Bob Kennedy to run operation,” Chicago Tribune, November 24, 1976: 41.

59 Jim Marshall, Treder interview.

60 Jim Marshall, Treder interview.

61 Jim Marshall, Treder interview.

Full Name

Rufus James Marshall

Born

May 25, 1931 at Danville, IL (USA)

Died

September 7, 2025 at , ()

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.