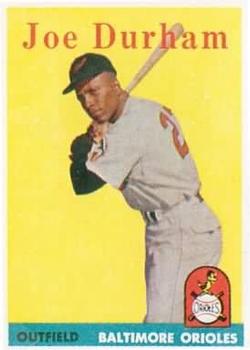

Joe Durham

Outfielder Joe “Pop” Durham played parts of three major league seasons for the Baltimore Orioles (87 games in 1954 and 1957) and St. Louis Cardinals (six games in 1959). He also played 10 years in the minors with a total of five teams. In 1954, Durham hit the first home run by an African American in modern Orioles’ history. After his playing career ended, he worked for the club for more than a half-century.

Outfielder Joe “Pop” Durham played parts of three major league seasons for the Baltimore Orioles (87 games in 1954 and 1957) and St. Louis Cardinals (six games in 1959). He also played 10 years in the minors with a total of five teams. In 1954, Durham hit the first home run by an African American in modern Orioles’ history. After his playing career ended, he worked for the club for more than a half-century.

Joseph Vann Durham was born on July 31, 1931, in Newport News, Virginia.1 He never knew his father, J. Vann Durham, a 22-year-old mechanic from Woodstock, Georgia, who died from lobar pneumonia two weeks before his son’s birth. Joe’s mother, Wilhelmina (Montgomery), was a maid for a private family. According to the 1940 Census, they lived with her three siblings and a niece in a home owned by her parents. Howard Montgomery, Joe’s grandfather, worked at a shipyard. When Joe was 10, his mother married Leslie Brandon, a sheet metal worker at the Norfolk Navy Yard. His half-siblings, Kenneth and Carolyn, were born in the 1940s.

Newport News, on the southeast end of the Virginia Peninsula and the north shore of the James River, was home to more than 180,000 residents by the first decade of the 21st century, but the population was less than 40,000 during Joe’s childhood. “Everything was segregated,” he recalled. “Schools, churches, everything,”2 including Builders’ Park, where Durham saw future stars like Gil Hodges play for the Brooklyn Dodgers’ Class B Piedmont League affiliate. “If you wanted to be a fan, the right field bleachers were the only place you could sit,” he recalled.3 “I never dreamed of playing ball professionally because we just weren’t allowed to play.” 4

He described his earliest baseball experience as “toying around” with sandlot teams in Newport News.5 He got serious about the game during his freshman year at Collis P. Huntington High School. When the team found itself without a catcher one day, Durham filled in. Though he soon switched to center field, he kept playing and batted at least .420 each year of his high school career.6 Asked to describe an interesting pre-professional experience, he mentioned a day in Portsmouth in April 1948 when he walloped four homers and two singles. By the time he graduated, he’d started earning seven or eight dollars a day traveling through Virginia and North Carolina with semipro teams like the Bombers, Tri-County Dodgers and Newport News Royals.7

Durham earned 13 sporting letters at Huntington. His speed — he ran the 100-yard dash in 9.8 seconds — made him a football and track standout.8 But basketball was where the 6-foot-1, 186-pounder really starred. When the Huntington Vikings won the Eastern District championship in 1948-49, Durham earned all-district honors and was named the tournament’s most outstanding performer.9 Before 1949 was over, he’d married Naomi McQueen, a laundress at the Chamberlin Hotel. Their son, Vann Arthur Durham, was born the following year.

After high school, Durham matriculated at Shaw University in Raleigh, North Carolina, to play basketball. When he was home, he worked as a receiving clerk at Fort Eustis and continued to play baseball for semipro teams. In 1952, New York Giants’ outfielder Willie Mays was stationed Fort Eustis. On weekends with the Newport News Royals, Durham shifted to left field to make room for the budding Hall of Famer in center.10

Durham was playing right field, however, when he earned his own shot at the pros. Assigned number 156 at a St. Louis Browns’ tryout camp, he fired a perfect one-hop throw to third base and became one of five players signed that day.11 However, the Browns’ only farm teams with room for an outfielder played in the segregated South where Durham was not welcome. Instead, he joined the Chicago American Giants, the Negro American League club run by St. Louis owner Bill Veeck’s friend Abe Saperstein. “I was in the Negro American League because I couldn’t play in anything else,” Durham explained.12 “People talk about [racism] in Mississippi and Alabama. Mississippi was bad, and Alabama was bad, but Chicago was just as bad as any of them.”13

The American Giants were managed by Winfield Welch, later a Phillies scout, who worked winters for Saperstein’s Harlem Globetrotters basketball barnstormers.14 Welch also skippered the West squad on August 17 in the 20th annual East-West Game, in front of 18,279 fans at Comiskey Park.15 Durham made the team as a reserve, joining shortstop Larry Raines as the only future big leaguers in what had been a talent-laden showcase (drawing crowds in excess of 40,000) before Jackie Robinson broke the majors’ color line. “Most of the guys on those teams [in 1952] were older,” Durham recalled. “There were several veterans that got my attention. I saw them play when I was a kid. Henry Kimbo (Kimbro) and Doc Dennis…these guys had been playing for ages.”16

In 1953, Durham and teammate Willie Tasby were two of a handful of African Americans who integrated the Class B Piedmont League. Consequently, some of the circuit’s cities were less than welcoming to the Browns’ York (PA) White Roses affiliate. “Tasby had a little problem,” Durham recalled. “He wanted to go up in the stands. I said, ‘There’s 1,800 people up there, and we are going up there to meet 1,800 people? You gotta be out of your mind.’ I said, ‘Let ‘em talk’.”17

Death threats were the most extreme obstacle Durham had to deal with, but logistical complications were chronic.18 “In Hagerstown, Richmond, Norfolk, you wouldn’t stay with the team,” he recalled. “Somebody asked me, ‘Was it hard to play?’ It made it harder. Baseball is a team game, a family game, and when the family is split, like I don’t see my teammates until it’s time to go to the ballpark, that’s tough.”19 “Black ballplayers of that era had to have a little something extra to go along with their playing talent because of things you had to endure. You had to tell yourself not to let anything get in your way or distract you. There was nothing you could do.”20 He batted .308 with 14 home runs. His 28 stolen bases led the league and his batting average ranked fourth.21 The All-Star Game was played in Newport News, where the local paper reported that an integrated crowd sat “shoulder-to-shoulder.”22 On another visit to his hometown, Durham’s homer gave York a 1-0 victory on August 21.23

That winter in the Colombian League, Durham had a .318 batting average through games of February 2 for the team owned by Willard International Batteries.24 Scout Fred Hofmann managed the club. Durham’s nine home runs established a short-lived circuit record that Horace Garner surpassed the following year.25

The Browns moved to Baltimore and became the Orioles in 1954, but Durham spent most of the year with the San Antonio Missions in the Double-A Texas League. He was closer to the majors, but still had to endure racist indignities. “We’d go into Shreveport, worst place in the world. The bleacher seats had a line with ‘white only’ on one side, and way down in the corner was the colored section. The [whites] would stand there and call me all kinds of names. I was there for one reason, to have a decent year and get promoted.”26

Durham enjoyed a fantastic season. He played in each of his team’s 161 games and batted .318 with 14 homers and 108 RBIs. He scored 102 runs, legged out a league-leading 17 triples and started the All-Star Game for the South squad. On August 12, however, he was told to report to the draft board in Newport News for induction into the United States Army. Durham appealed, noting that he was the sole support for his son and grandmother since his divorce had been finalized in spring training.27 The Army granted him a 60-day extension, allowing him to finish the baseball season.28 The reprieve allowed Durham to be called up to the majors in September. “One player took me under his wing, Don Larsen,” he recalled.29 “He had a brand new ’54 Oldsmobile and he used to pick me up…Otherwise, I would have had to spend money on cabs. I couldn’t afford a car.”30

On September 10, 1954, Durham made history as the first African American to start a game for the Orioles, batting third and playing left field.31 Although he dropped a line drive for an error, the local paper reported that he impressed by driving a 400-foot out in his second at-bat, and making a strong fourth-inning throw that drew cheers. Durham was 0-for-3 with a walk before he batted with two outs in the bottom of the ninth against Senators’ southpaw Mickey McDermott. Baltimore trailed by one with the tying runner aboard. After Durham beat out an infield hit on a slow roller to third, Bob Kennedy doubled to even the score, and Frank Kellert followed with a single to plate the rookie with the winning run. “Running around the bases here last night [Durham] lost his cap — Willie Mays style — twice,” reported the Baltimore Sun.32

Durham hit safely in his first five games, including an historic clout in the second game of a September 12 doubleheader. When he pulled a hanging slider from Athletics’ lefty Al Sima over the left field fence leading off the bottom of the sixth, it was the first home run ever hit by a black man for the Baltimore Orioles. “Once I hit it, I knew it was gone,” Durham said. “I got good wood on it.”33 He recalled that nobody noted the significance of the blow until a few days later. When an elderly woman approached him after the game to hand him the home run ball, Durham offered her money, which she refused to accept. Sixty years later, he joked that it was a good thing that she declined because he didn’t have any.34

In the final week of the season against the Tigers, Durham enjoyed his only three-hit game in the majors. He told Baltimore’s Afro-American newspaper that he had no hobbies, before adding, “I do like to travel if you can class that as a hobby.”35 After batting .225 in 10 games for the Orioles, Durham spent the next two years in the service: at Camp Gordon in Georgia, then with the Seventh Army in Germany.36

During spring training 1957, Durham led the Orioles with a .296 batting average, prompting manager Paul Richards to tell reporters, “That boy could develop into a major league star.”37 With the outfield full in both Baltimore and Triple-A Vancouver, however, Durham began the year back in San Antonio. He was batting a league-leading .391on June 10 when he was told to fly to Detroit. The Orioles needed him to replace Francona, who’d broken a bone in his left hand.38 In his first game back, Baltimore beat the Tigers behind Connie Johnson’s complete-game effort, and another veteran of the Negro leagues, Bob Boyd, had three hits for the Orioles. Durham contributed one of his own and made two outstanding catches in center field. “I knew [Durham] could go get ‘em,” remarked Richards. “He really showed them some foot out there, didn’t he?”39

At bat, however, Richards believed the way Durham lunged at pitches and uppercut prohibited him from being an effective hitter, no matter how consistently hot the outfielder had been since spring training. After a Sunday afternoon game in Baltimore, the manager tried an unusual corrective measure. “[Richards] was standing on the other side of the cage and got a harness around my waist,” Durham recalled. “They threw pitches and, when I went to swing, they grabbed the rope and pulled so I couldn’t move too much…That was an experience. It happened one time. They never tried it again. And they called the guy a genius?”40

When manager Cal Ermer tried something similar with Don Lock at Triple-A Richmond in 1961, the article describing it in The Sporting News suggested that the rope trick may have once helped Joe DiMaggio.41 Durham, however, remained bothered by the stunt. “Today, a manager wouldn’t dare try anything like that,” he remarked nearly a half-century later.42 “That rope experiment didn’t do any good. George Kell, who was with us that year. was the biggest lunger in the world, and he had won a batting title.”43

Durham started 17 straight games upon joining the Orioles, but never more than two in a row after that despite remaining with the team for the remainder of the year. His opposite-field single off Chicago’s Jim Wilson on September 18 proved to be the last hit of his big league career. He went hitless in his last 13 at bats of 1957 and finished with a .185 average and four homers in 77 games. “I thought I did a pretty good job for the Orioles whenever Richards let me play,” Durham said. “But every time I thought I was settled for regular duty, they sat me on the bench.”44

That winter, Durham was nearly sent home early from the Venezuelan League after he started slowly with the Leones del Caracas, but he rebounded to bat .290 in 36 contests.45 “Too much changing around can get a fellow confused,” he explained. “I did pretty well in South America with a little shorter stride.”46

Durham’s changes in 1958 included his second wedding. He married Sallie Stevenson in Chester, South Carolina, before spring training. They would welcome a son, Steven, and daughter, Melanie, by the mid-1960s. After the Orioles reacquired veteran outfielders Gene Woodling and Dick Williams two weeks before Opening Day, Durham was sent to the Triple-A Vancouver Mounties. Early in the Pacific Coast League season, his jaw was broken by an up-and-in pitch from Portland’s John Buzhardt.47 Durham came back to play 135 games and bat .285, however, including a club-best 18 homers and 85 RBIs. It wasn’t enough to convince Richards to bring him back to Baltimore.

Changes kept coming. While Durham was playing winter ball in the Caribbean, the St. Louis Cardinals nabbed him in the Rule 5 draft. “I have no idea how things are going to work out for me in the Cardinal organization,” he said. “But I have a feeling I’m going to be much happier.”48 He was happy to get away from Richards. “The man was a hypocritical, racial son of a bitch,” Durham insisted later.49 In spring training 1959, Durham told the Afro-American’s Sam Lacy, “His treatment of me isn’t the basis for my suspicions of Richards. Instead, it is the way he manhandles Bob Boyd and Connie Johnson.” Though Boyd and Johnson had produced Baltimore’s top batting average and win total in 1957, they spent half of 1958 on the bench and in the bullpen, respectively. Durham insisted that was enough to “make you wonder about [Richards]…and his deep-down thinking.”50

Durham made the Cardinals’ Opening Day roster, but appeared in only six games, going hitless in five at bats. On May 1 in Pittsburgh, he pinch-ran for Stan Musial and scored his last run in the majors. Five nights later in Philadelphia, he grounded out to second baseman Sparky Anderson in his final big league at bat. In 93 games in the majors, he batted .188 with five home runs.The Cardinals returned Durham to the Orioles organization a few days later and recovered half of the $25,000 that they’d paid to draft him. He returned to Vancouver for a May 10 doubleheader and collected four hits including a homer.51

By June 15, though, Durham was batting only .230.52 A red-hot 14-for-21 stretch from July 9-13 earned him a “Durham Swings Hot Bat” headline in The Sporting News.53 Ten days later, he’d moved into a tie for the Mounties’ club lead in RBIs, but he fractured his wrist in an outfield collision with Barry Shetrone and missed the rest of the season.54 Durham played five more seasons in Triple-A, at Vancouver and Rochester. In 1962 he was named to the National Association All-Star Fielding Team as one of the most sure-handed glove men in the minors and received a silver glove from Rawlings.55 In December, however, he was traded to the International League’s Richmond Virginians for second baseman Don Brummer. According to the Baltimore Sun, the deal was initiated by Richmond’s parent club, the Yankees.56 “I was a little sad because I had two pretty good years at Rochester,” Durham admitted. “But I started thinking and I realized Rochester had to get rid of an outfielder. Sam Bowens is a prospect. They have a lot of money in Earl Robinson. They think a lot of Fred Valentine. That left me.”57

Richmond’s Times Dispatch reported that Durham struck out in his first at bat on Opening Day and never got into a groove. “It’ll be my first bad season,” he said. “I’ll just have to concentrate on bouncing back next year.” With Durham struggling to catch up with good fastballs, Yankees batting coach Wally Moses visited in June and reconstructed the almost 32-year-old’s stance. “Players don’t lose their reflexes when they’re that young,” Moses insisted.58 He finished the season batting .244 with 13 homers. In 1964 he returned to Rochester for his final season as a pro. The Red Wings won the Governor’s Cup, but Durham batted just .239 with six homers.

Durham was out of baseball by spring training 1965. He remained with his family in the Baltimore suburb of Randallstown, where he began a long career as a salesman for Churchill Limited liquor distributors. By the late 1960s, he had a part-time job hurling batting practice for the Orioles. For more than two decades, he’d show up at Memorial Stadium three hours early for every home game and hurl 150-180 pitches. “I let ‘em hit it. You’re not trying to fool anyone,” he explained. “Batting practice is a confidence builder and, if a hitter can hit four straight in the stands off me, he believes he can do it in a game.”59

In 1970, Durham helped the Orioles win the championship. “I went to Cincinnati to pitch BP in the opening game of the World Series,” he recalled. “Boog [Powell came out and hit the first three into the seats –whoom, whoom, whoom. It made me feel great.”60 (Powell’s two-run homer helped win the game that afternoon, 4-3). Baltimore manager Earl Weaver brought Durham to the 1972 All-Star Game in Atlanta to warm up the American Leaguers.61 During winters, he played for the Orioles’ charity basketball team, and officiated high school and college sports around Baltimore. When Rochester invited him to play in an old-timer’s game in 1986, he doubled and scored his first time up, In his second at bat, the 55-year-old ripped a two-run homer off Steve Grilli.62

After the 1987 season, the Orioles hired Durham to join their front office as a community coordinator, visiting schools and giving clinics. From 1990 to 1995, he coached for three of the organization’s Maryland-based minor league affiliates — Hagerstown, Bowie and Frederick. He scouted for one year. “No player has spent more years in the Orioles’ organization than Joe Durham,” reported the Baltimore Sun.63 “I’ve been on their payroll in some capacity since 1954,” Durham told an interviewer as his tenure with the team stretched into a sixth decade.64 As an octogenarian, he continued to make autograph appearances at Camden Yards.

Late in his life, Durham discovered how much his struggles as a racial pioneer had inspired others. “I didn’t realize it until after I had finished playing,” he said. “You go back, get invitations to different places, and that’s what they talked about, the integration or infiltration of black players in baseball, especially in the South.”65 In 2008, Durham was inducted into the Hampton Roads African American Sports Hall of Fame.66 Paradoxically, the increased appreciation for Durham’s accomplishments coincided with declining numbers of African American major leaguers. “I hope I’m wrong, but it looks like it’s a thing of the past,” he said. “Baseball’s too slow and dull for them, and it’s the hardest of all the games to play.”67

On Thursday April 28, 2016, Joseph Vann Durham died of natural causes in Randallstown. He was 84. The Orioles honored him with a moment of silence before taking on the White Sox that evening at Camden Yards. “Joe lived, ate and dreamed baseball,” said Sallie, his wife of 58 years. “When we left the hospice center Wednesday night, my daughter put the Orioles game on TV for him. Joe couldn’t open his eyes, but the nurses said he could still hear.”68 He is buried at Garrison Forest Veterans Cemetery in Owings Mills, Maryland.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed Eric Vickrey and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

Dominican League statistics from https://stats.winterballdata.com/players?key=4457 (subscription service).

Venezuelan League statistics from http://www.pelotabinaria.com.ve/beisbol/index.php

In addition to the sourced cited in the Notes, the author also consulted www.ancestry.com, www.baseball-reference.com, www.retrosheet.org and the 1940 U.S. Census.

Notes

1 Often, during Durham’s playing career, his birth year was erroneously reported as 1932. His bio on page 11 of the 1957 Baltimore Orioles media guide is just one example of this.

2 John Eisenberg, From 33rd Street to Camden Yards, (New York: Contemporary Books, 2001): 63.

3 Jonathan Mayo, “From the Field to the Stands,” February 25, 2008, https://www.milb.com/news/gcs-350776 (last accessed December 29, 2020).

4 Nathan Hyde, “Joe Durham: Orioles Pioneer,” February 12, 2014, https://patch.com/maryland/owingsmills/joe-durham-orioles-pioneer_6cc4cc78 (last accessed December 29, 2020).

5 Herb Mangrum, “Orioles,” Afro-American (Baltimore, Maryland), September 25, 1954: 17.

6 Hyde, “Joe Durham: Orioles Pioneer.”

7 Joe Durham, Publicity Questionnaire for William J. Weiss, May 13, 1953.

8 Joe Durham, 1958 Topps Baseball Card.

9 Bill Rogers, “Legends Get Their Due in Hampton Roads African American Sports Hall of Fame,” August 6, 2008, http://thestlbrowns.blogspot.com/2008/08/legends-to-get-their-due-in-hampton.html (last accessed December 29, 2020).

10 Hyde, “Joe Durham: Orioles Pioneer.”

11 Hyde, “Joe Durham: Orioles Pioneer.”

12 Mayo, “From the Field to the Stands.”

13 Hyde, “Joe Durham: Orioles Pioneer.”

14 “Phils Sign Welch as Talent Scout,” Philadelphia Tribune, October 21, 1958: 10.

15 Larry Lester, Black Baseball’s National Showcase: The East-West All-Star Game, 1933-1953, (Lincoln, Nebraska, University of Nebraska Press, 2001), 362-374.

16 Nick Diunte, “Joe Durham, 84, First African-American to Hit a Home Run for the Baltimore Orioles,” April 30, 2016, https://www.baseballhappenings.net/2016/04/joe-durham-84-first-african-american-to.html (last accessed December 30, 2020).

17 Bob Luke, Integrating the Orioles, (McFarland & Company, Inc: Jefferson, North Carolina, 2016): 27.

18 Tom Robinson, “Black Baseball: Saving the Past as the Future Turns its Back,” Virginian-Pilot (Norfolk, Virginia), June 17, 2007, https://www.pilotonline.com/sports/columns/article_3c2126d6-b85c-5e5b-a7b8-546e275d7083.html (last accessed December 29, 2020).

19 Eisenberg, From 33rd Street to Camden Yards: 63.

20 Diunte, “Joe Durham, 84, First African-American to Hit a Home Run for the Baltimore Orioles.”

21 “Joe Durham, Orioles’ Young Flyhawk, Inducted by Army,” The Sporting News, December 1, 1954: 30.

22 Mayo, “From the Field to the Stands.”

23 “Minor League Highlights Class B,” The Sporting News, September 2, 1953: 36.

24 “Colombia Clouters,” The Sporting News, February 10, 1954: 32.

25 Alvaro Cepeda Samudio, “Colombian Loop Homer Record Set by Garner,” The Sporting News, December 1, 1954: 32.

26 Eisenberg, From 33rd Street to Camden Yards: 63.

27 “Army Beckons Missions Slugger,” The Sporting News, August 4, 1954: 29.

28 “Joe Durham Gets Extension,” The Sporting News, August 11, 1954: 33.

29 Hyde, “Joe Durham: Orioles Pioneer.”

30 Louis Berney, Tales from the Orioles Dugout, (Sports Publishing: Champaign, Illinois, 2007): 8.

31 Baltimore’s first African American major-leaguer, Jay Heard, made two relief appearances earlier in the 1954 season.

32 Ned Burks, “2 New Rookies Help Birds Nip Senators in 9th, 4-3,” Baltimore Sun, September 11, 1954: 11.

33 Hyde, “Joe Durham: Orioles Pioneer.”

34 Hyde, “Joe Durham: Orioles Pioneer.”

35 Mangrum, “Orioles.”

36 Diunte, “Joe Durham, 84, First African-American to Hit a Home Run for the Baltimore Orioles.”

37 Jim Ellis, “Birds Take Wing Despite Injuries to Kell, Francona,” The Sporting News, June 19, 1957: 20.

38 Ellis, “Birds Take Wing Despite Injuries to Kell, Francona.”

39 Mike Klingaman, “Joe Durham, First African-American Player to Homer for Orioles, Dies at 84,” Baltimore Sun, April 29, 2016: D5.

40 Eisenberg, From 33rd Street to Camden Yards: 62.

41 “Ermer Tries Rope ‘Cure’ for Overstriding Slugger,” The Sporting News, June 21, 1961: 21.

42 Eisenberg, From 33rd Street to Camden Yards: 62.

43 Doug Brown, “An Oriole Since ’54 Season, Durham Remains in the Nest,” Baltimore Sun, September 21, 1995: 7D.

44 Sam Lacy, “Sports by the Afro,” Afro-American, March 28, 1959: 13.

45 M. J. Gorman, Jr. “Orioles Duo Gives Lions New Hope,” The Sporting News, November 13, 1957: 24.

46 “Joe Durham Hopes to Regain Batting Form with Orioles,” Atlanta Daily World, March 9, 1958: 8

47 “Mounties Lose Held, Durham,” The Sporting News, April 23, 1958: 29.

48 Sam Lacy, “Sports by the Afro,” Afro-American, March 28, 1959: 13.

49 Eisenberg, From 33rd Street to Camden Yards: 62.

50 Lacy, “Sports by the Afro.”

51 “Vancouver,” The Sporting News, May 20, 1959: 40.

52 “Vancouver,” The Sporting News, June 24, 1959: 28.

53 “Durham Swings Torrid Bat,” The Sporting News, July 22, 1959: 35.

54 “Vancouver,” The Sporting News, August 5, 1959: 38.

55 Klingaman, “Joe Durham, First African-American Player to Homer for Orioles, Dies at 84.”

56 “Durham Goes to Richmond,” Baltimore Sun, December 22, 1962: S18.

57 Shelley Rolfe, “Parker Field Not No. 1 in the IL for Durham” Times Dispatch (Richmond, Virginia), March 28, 1963: 16.

58 “End to Durham’s Slump Could Start Vees’ Rise,” Times Dispatch, June 30, 1963: 38.

59 Ken Nigro, “This Oriole Pitcher Loves to Get Shelled,” Baltimore Sun, September 22, 1974: S4.

60 Nigro, “This Oriole Pitcher Loves to Get Shelled.”

61 “Campaneris to Start for Aparicio on American League All Star Team,” Hartford Courant, July 22, 1972: 26B.

62 “Old-Timer Hasn’t Lost Timing,” Baltimore Sun, August 24, 1986: 28.

63 Doug Brown, “An Oriole Since ’54 Season, Durham Remains in the Nest,” Baltimore Sun, September 21, 1995: 7D.

64 Diunte, “Joe Durham, 84, First African-American to Hit a Home Run for the Baltimore Orioles.”

65 Mayo, “From the Field to the Stands.”

66 Rogers, “Legends Get Their Due in Hampton Roads African American Sports Hall of Fame.”

67 Robinson, “Black Baseball: Saving the Past as the Future Turns its Back.”

68 Klingaman, “Joe Durham, First African-American Player to Homer for Orioles, Dies at 84.”

Full Name

Joseph Vann Durham

Born

July 31, 1931 at Newport News, VA (USA)

Died

April 28, 2016 at Randallstown, MD (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.