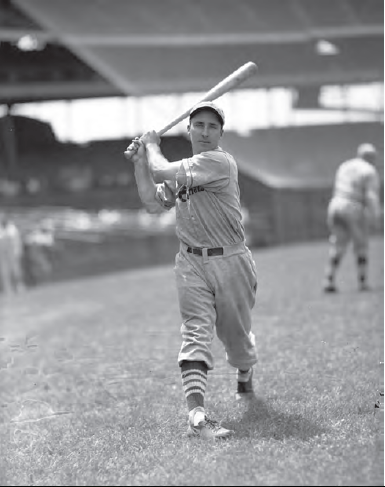

Ripper Collins

Ruggedly handsome with dark wavy hair, an engaging smile and a boyish grin, the 1934 St. Louis Cardinals’ first baseman was equally capable of leading the league in both home runs and pranks. General manager Branch Rickey suspiciously called him the instigator, to which James Anthony Collins remarked: “Rickey always accused me of being the ringleader; I never could understand why he picked on me — unless it could have been because there was considerable truth in his allegations.”1.

Ruggedly handsome with dark wavy hair, an engaging smile and a boyish grin, the 1934 St. Louis Cardinals’ first baseman was equally capable of leading the league in both home runs and pranks. General manager Branch Rickey suspiciously called him the instigator, to which James Anthony Collins remarked: “Rickey always accused me of being the ringleader; I never could understand why he picked on me — unless it could have been because there was considerable truth in his allegations.”1.

Collins was born in Altoona, Pennsylvania, on March 30, 1904. His father, William Collins, was of Irish and Scottish descent, while his mother, Elizabeth, traced her heritage back to Germany. At the recording of the 1920 census, James was 15; sister, Arietta, was 12, and his brother, William, was 2. Both young James and his dad listed coal miner as their profession; Jimmy started working in the mines at 13.

The Collins family moved to Johnstown, Pennsylvania, where young Jimmy attended nearby Nanty Glo Elementary. His father played semipro baseball and the first time Jimmy saw him crush a fastball, it became his goal to follow in his dad’s footsteps. During the cold, snowy Pennsylvania winters, Jimmy honed his skill, spending countless hours fielding grounders off a basement wall. When summer arrived he was on the ball field from sun-up to sundown.

Full-time school ended for Jimmy at the age of 14, when he took a job in the shipping department of the mine. Simultaneously, he attended night school — a common practice for boys his age in a coal-mining town. His dad, now a machinist, played ball on the company team. Jimmy joined the team and the father/son duo roamed left and center fields respectively. Jimmy originally threw left-handed and batted right-handed. The senior Collins, noting a short right-field fence at the company field, taught Jimmy to bat left and throw both left- and right-handed. Jimmy adapted to switch-hitting and continued to hit from both sides throughout his career.

The nickname Ripper developed during an on-field incident that occurred when Jimmy was a young player. A ball rocketed off his bat and struck a nail protruding from the outfield fence; it caused the cover to partially tear. When asked who hit the ball, the retrieving outfielder saw the ball hanging and said, “It was the ripper.”2

In 1922 Jimmy married Helen Fasemeyer, also from Nanty Glo. At the time he was only 17 and couldn’t legally get a marriage license in Pennsylvania. The couple decided to elope and drove to Cumberland, Maryland, to have the ceremony performed. As a young married man, Jimmy not only worked hard in the mines — he played ball even harder, hoping a scout would notice. Marriage immediately affected Collins’s sense of responsibility: “From that day on, I knew I had to make the grade in baseball. Handicapped by my lack of education, I realized that if I failed as an athlete, my life would be a dull, pitiful existence as a coal miner.”3 The couple had a son (also Jimmy) in 1923; a daughter, Betty, arrived in 1925 and another son, Warren, in 1930.

The lack of a paycheck during a mine strike in 1922 resulted in Ripper’s signing his first professional contract, debuting in class C ball with York, Pennsylvania, of the New York-Penn League; he later shifted to Wilson, North Carolina, in the Virginia League, seeing only limited playing time at each stop before returning home to the mines.

In 1925 a lengthy strike put thousands of miners out work. Again with no paycheck and time on his hands, Collins approached the hometown Johnstown club of the Mid-Atlantic League for a tryout and impressed enough to be offered a $200 signing bonus — just about enough money to get the young family out of debt. Jimmy hit .327 in 99 games and suddenly scouts from higher classifications began to hover. George Stallings, then manager of the Rochester Red Wings and formerly a pretty fair minor-league ballplayer in his own right, saw Collins play and remarked: “I wouldn’t give $5.00 for him.”4 A dejected Rip went back to the mines and his father recommended that he forget baseball.

In 1926 Johnstown was in a tough pennant fight. This time Ripper’s .313 average in 102 games got him promoted to Double-A Rochester late in the season; the club was experiencing financial difficulties and players were not getting paid. Rip’s performance suffered and he again returned to the mines.

Farmed out to Savannah in 1927, Collins was recalled by Rochester at the end of the season. Subsequently, the troubled franchise was sold to the St. Louis Cardinals and housecleaning started, with almost the entire squad placed on waivers. Collins survived, but was demoted back to Class B, making stops in Savannah and Jacksonville before returning to Rochester at the end of the season, where a lackluster .246 average got him demoted to Danville, Illinois, of the Three-I League. At this point, Collins’s father wrote a long letter urging him to realize he wouldn’t make it and recommended that he resume working in the mines. Despite his father’s plea, Collins stayed in the Three-I league and ultimately led the loop with a .388 average in 1928, earning him a return trip to Rochester, where he posted an impressive .375 batting mark in 14 games. The Cardinals ordered Collins to report for spring training in 1929 with the parent club.

This time Collins’s mother urged him to report, saying she had a feeling it was going to be his big break. Sure enough, Cardinals manager Billy Southworth was impressed and recommended that Collins learn to play first base. Despite not being a prototypical build (5-feet-9, 165 pounds) for the position, he had cat-like reflexes, plus an uncanny ability to pull down errant throws and scoop low tosses out of the dirt.

Thanks to a cash infusion from the parent Cardinals, Rochester opened a brand-new stadium in 1929 and Ripper christened the ballpark on May 2, hitting the first home run in the Red Wings’ new home. All told, he hit .315 with 38 homers and 132 runs batted in. In 1930 he led the International League with a .376 average and an eyebrow-raising 40 home runs, while batting in a league record 180 runs. Collins was clearly instrumental in helping the Red Wings win pennants in 1928, 1929, and 1930 and blossomed into a definite major-league prospect.

Collins earned a promotion to the Cardinals and made his major-league debut in 1931, playing 89 games as a backup to Jim Bottomley. He posted a respectable .301 average, with 4 home runs and 59 RBIs, as a pinch-hitter and part-time first baseman/outfielder. Collins described to Arthur Daley of the New York Times how manager Frank Frisch once considered using him at third base when he was short an infielder; Collins was eager to play the position right-handed and said he regretted not having the opportunity.5

Collins’s playing time increased to 149 games in 1932 and his home run total rose to a healthy 21; in 81 games at first base, he had a .999 fielding average. So promising was Collins that the Cardinals traded Bottomley to Cincinnati after the season.

In late July 1933, Gabby Street was replaced as the Cardinals’ manager. Popular second baseman Frisch succeeded him. A fellow switch-hitter, Frisch worked with Collins and helped him become a more patient and disciplined hitter. He taught the stocky first baseman to choke the bat for better control and worked with him to improve his bunting skills from both sides of the plate. In general, Collins drove the ball for longer distances left-handed and stroked wicked line drives batting right-handed. According to author Rob Rains, Collins was “one (Cardinal) who knew how to play and when to be serious, Frisch’s type of guy, was the versatile Collins.”6. Collins contributed a .310 batting average with 10 home runs and 68 RBIs.

Collins enjoyed a breakout season in 1934, when his .333 average helped spark the Cardinals to the National League pennant and a World Series title. He became the first switch-hitter in the major leagues to hit 30 home runs in a season, winding up with 35 and tying for the league lead with the Giants’ Mel Ott. (This became the single-season standard for switch-hitters until Mickey Mantle surpassed Collins with 37 homers in 1955.) All but four of Collins’ home runs were hit left-handed; he had 200 hits, 40 doubles, 12 triples, 128 RBIs, and a league leading .615 slugging percentage. He led National League first basemen with 110 assists.

Along with Gas House Gang teammates Pepper Martin, Dizzy Dean, and Dazzy Vance, Collins sang on KMOX radio in St. Louis. They formed a washboard-style band called the Mississippi Mudcats and regularly performed in the team’s clubhouse and hotel. At the Bellevue-Stratford in Philadelphia in 1936, fun-loving Pepper Martin “noticed ladders, paint buckets, white overalls, and other painter’s paraphernalia in a corner of a service area. He rounded up Collins, Dizzy Dean, Heinie Schuble, and Bill DeLancey. They donned the overalls, took the equipment into a busy dining room and began painting the walls and ceiling, splattering paint on the customers, shouting instructions to one another à la the Marx brothers and promoting general chaos.”

During the hard-fought 1934 pennant race, Collins was approached to author a series of daily newspaper articles in St. Louis and also for his hometown Rochester Times Union. He reported the baseball news and added commentary from roommate Pepper Martin. Two dictionaries accompanied Ripper on road trips, but neither did him any good: “I’ve pondered through both of them, but I’ve never run across any of Frankie Frisch’s language. I now plan to write a ballplayers’ dictionary. I’ll gather all the pet words and answers from the players around the league. That book ought to be a best-seller.” One day after striking out, Collins was taken to task when frustrated manager Frisch remarked: “Next time, swing your typewriter.”8

The seventh and deciding game of the hard-fought 1934 World Series took place on October 9 at Navin Field in Detroit. The Cardinals supported winning pitcher Dizzy Dean with 11 runs to gain the victory. Batting fifth in the order, Collins led the offensive barrage with four hits. In the eighth inning he lost a potential fifth hit when his drive sent center fielder Jo-Jo White back to the 420-foot marker at the wall in right-center. White leaped, deflected the ball off his glove, and snagged it while lying on his back. Collins hit .367 for the Series.

On May 11, 1935, Collins took Philadelphia Phillies right-hander Euel Moore deep, hitting career home run 74, the major-league record at the time for switch-hitters. For the season Collins hit .313 with 23 round-trippers. On August 21 an unusual feat occurred when he played an entire game at first base without a putout. Collins placed in the top ten in several batting categories for the ’35 season.

The efficient Cardinals farm system produced hard-hitting Johnny Mize, who appeared in 126 games (99 at first base) in 1936 and made Collins expendable. After the season he was traded to the Chicago Cubs with pitcher Roy Parmelee for pitcher Lon Warneke.

Wearing a Cubs uniform in 1937, Collins on June 29 again played an entire game at first base without recording a putout; this time also without an assist. He jokingly offered to pay the price of one admission ticket because “I was strictly a spectator.”9

On August 9, 1937 the Cubs were leading the National League pennant race by six games when the team visited Cook County jail in Chicago. Collins thought it great fun to jokingly take a seat in the electric chair. Superstitious teammates chided him for doing what they considered to be an omen of bad luck. In the first inning the next day, Collins fractured his right ankle sliding into home plate. The Cubs lost the game to the Pittsburgh Pirates and nosedived to ultimately lose the National League flag to the New York Giants.10 Collins was never quite the same player, either at bat or in the field. All told in 1937, he appeared in 115 games, with 16 homers, 71 RBIs and a .274 batting average.

In 1938 Collins’s playing time increased to 143 games. He hit.268 with 13 home runs and a league-leading fielding average of .996. Sparked by catcher-manager Gabby Hartnett’s memorable Homer in the Gloamin’, the Cubs edged the Pirates to win the National League flag. Prior to the start of the World Series, Collins and teammate Billy Jurges visited 14-year-old Johnny English at Mercy Hospital in Chicago. An ardent Cubs fan, young Johnny was ill with cancer and wasn’t expected to live to the end of the season, let alone the World Series. Collins and Jurges brightened the boy’s spirits with the visit, accompanied by autographed baseballs signed by every member of the team.11 The Cubs were swept by a tough New York Yankees club. Commenting after being pummeled by the Bombers, the affable Collins remarked: “We came, we saw and we went home.”12

Collins was sold to the Pacific Coast League Los Angeles Angels on March 30, 1939; the media speculated that Hartnett was seeking to protect his job from a potential rival. Settling in as the Angels first baseman, Collins responded nicely by hitting .334 with 26 home runs in 172 games. Back for an encore season with the Angels in 1940, he hit .327 with 18 homers in 174 games.

Collins was back in the major leagues when he was purchased by the Pirates on March 25, 1941; the move reunited him with his former St. Louis manager Frankie Frisch. His acquisition was intended to ease the workload of first baseman Elbie Fletcher. Collins played in 49 games, hitting .210, in what became his last hurrah as a major-league player. He was released after the season. The move gave him his first opportunity to manage in professional baseball when he was installed as player-manager of the Class A Albany Senators of the Eastern League, a Pirates farm team. Attendance in Albany had been lagging for years and Collins was viewed as a potential draw, since he was a fan favorite in New York.13

The Collins family had resided in Rochester since Rip’s playing days; he managed a bowling alley in the city during the offseason. The Collins home was easily recognizable; Rip’s collection of broken bats surrounded it as a makeshift fence. His house stored his league-leading (estimated at over 10,000 items) collection of signed baseballs and bats. Collins, with boyish grin and tongue in cheek, defended the size of his collection by mentioning how neighborhood kids and deliverymen “kept his collection from getting too big.” A favorite bat in his collection was an ornate miniature given to Dizzy Dean by a Mexican fan to commemorate Dean’s fine 1934 season. Collins admired the bat to the point of “borrowing” it for his collection. Suspecting that Dean might become suspicious, Ripper had the bat carved to read: “To James Rip Collins — from Dizzy.” Collins estimated that he owned owning more than 3,000 autographed celebrity photos from many sports.14

A favorite glove in his collection was a “good luck” charm from the 1934 pennant race. Wild Bill Hallahan lost his glove during the stretch run and Rip loaned the lefty pitcher one of his well-worn four-fingered models. Hallahan proceeded to win every game he pitched wearing the borrowed glove. He asked Ripper if he could purchase the glove but Collins said no and the glove went back into his personal collection. Once asked how one man could collect so many baseball artifacts, Collins replied: “One man couldn’t. Darn every guy in the game knows it’s my hobby. When they see anything that looks good they pass it along.”15

In addition to serving as Albany’s skipper, Collins filled in at first base in 1942. He hit .276 in 118 games, but his home-run production fell to only 3 as the club finished first in the league but lost in the initial round of the playoffs. Remaining in Albany as player-manager in 1943, Collins batted .312 in 82 games with one home run as the club fell to 5th place. The wartime player shortage had Ripper back playing regularly at first base in 1944, seeing action in 100 games. At 40 years old he was named the outstanding minor-league player of 1944 by The Sporting News, hitting .396 for his second-place Albany Senators.

After five seasons, Collins resigned as Albany’s manager on November 27, 1946, to become manager of the Pacific Coast League San Diego Padres, where he replaced Pepper Martin. Albany owner Tom McCaffrey commented: “Ripper has been a splendid manager and I’m sorry to lose him. I have long known he deserves a promotion and I’m glad for his sake that he is going higher. He has been Albany’s most popular manager.”16

In 1947 San Diego finished dead last in the PCL. On August 3, 1948, after losing 13 of 17 games, Collins was ousted as manager. The move was unpopular with fans and the local media; Collins took the move in stride, citing player injuries as the source of his troubles. His next managerial slot was back in the Eastern League, with the Hartford (Connecticut) Chiefs for 1949 and 1950. Although he signed to run the club for a third year, he resigned to capitalize on an opportunity to go to Baltimore and become a color commentator in the new medium of television.

Still one to enjoy a laugh, Collins was up to his old tricks again when he couldn’t resist entertaining the crowd at a 1950 old-timer’s game in the Polo Grounds in New York with the old hidden-ball trick. The amused umpires investigated and found several baseballs in the pockets of many of the Cardinal players.17

Collins was elected to the International League Hall of Fame in 1951. He went to work for Wilson’s Sporting Goods, for whom he authored a “how-to” manual for youngsters devoted to teaching proper baseball technique. He left Wilson to return to baseball as a roving minor-league instructor with the Chicago Cubs. During spring training 1961 Collins became a coach with the parent club and was part of the College of Coaches experiment initiated by owner Phil Wrigley. His last stint managing in the minor leagues was later in 1961 with San Antonio in the Texas League. Collins also worked in the Cubs’ public-relations office and hosted the Meet the Cubs radio show.

A model athlete on and off the field, Collins was accessible and liked mixing with fans during personal appearances. He thoroughly enjoyed pleasing people and believed players should always be considerate and thoughtful. He never failed to answer a fan letter and especially enjoyed personally writing to youngsters. He was polite, affable, and a non-swearing type — who simply enjoyed a little good-natured fun. He said, “Left-handers are not screwballs. … We have color.”19

Collins hit over .300 in four of his nine big-league seasons. His 135 home runs were tops among major-league switch-hitters until Mickey Mantle surpassed him. A clutch hitter, Collins referred to himself as “the All-American Louse,” a moniker he chose after breaking up four no-hitters during his major-league career. He was elected to the Rochester Red Wings Hall of Fame in 1989.

In the spring of 1969 Collins, scouting for the Cardinals, was hospitalized in Oswego, New York, after suffering a serious heart attack. On April 15, 1970, at the age of 66, Ripper had to a fatal attack in New Haven, New York. He is buried in Mexico Village Cemetery, Mexico New York.

Notes

2 Robert E. Hood, The Gashouse Gang (New York: William Morrow & Co. 1976).

3 Harry T. Brundidge, The Sporting News, March 9, 1933.

4 Ibid.

5 Arthur Daley, “Sports of the Times,” New York Times, January 20, 1957.

6 Rob Rains, The St. Louis Cardinals: 100th Anniversary History (New York: St. Martin’s Press. 1992).

7 The Sporting News, May 2, 1970.

8 “Rip the Writer Consults Dictionaries,” Raleigh Register (Beckley, West Virginia), June 25, 1936.

9 San Mateo (California) Times, March 9, 1959.

10 Life Magazine, September 9, 1937, 22.

11 “Boy Lives to See Cubs Win,” Arizona Republic (Phoenix, Arizona), October 6, 1938.

12 Helena (Montana) Daily Independent, October 10, 1938.

13 The Sporting News, November 27, 1941.

14 “Rip Collins is No.1 Collector of Broken Bats,” Oshkosh (Wisconsin) Northwestern, February 22, 1937.

15 (Ibid).

16 Dick Connors, “Collins Succeeds Old Roomie at San Diego,” The Sporting News,” November 27, 1946.

17 “Old Cards Pull Hidden Ball Trick on Giants,” Washington Post, July 31, 1950.

19 Gene Henschel, “Rotarians Hear Collins Describe Career,” Sheboygan (Wisconsin) Press, September 1, 1964.

Full Name

James Anthony Collins

Born

March 30, 1904 at Altoona, PA (USA)

Died

April 15, 1970 at New Haven, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.