Rudy May

Near the end of his long major-league career, Rudy May said, “I learned that it’s better to throw an 85 mile an hour fastball on the outside corner than it is to throw a 95 mile an hour fastball down the middle.” Asked when he discovered that, he replied, “When I couldn’t throw a 95 mile an hour fastball anymore.”1

Near the end of his long major-league career, Rudy May said, “I learned that it’s better to throw an 85 mile an hour fastball on the outside corner than it is to throw a 95 mile an hour fastball down the middle.” Asked when he discovered that, he replied, “When I couldn’t throw a 95 mile an hour fastball anymore.”1

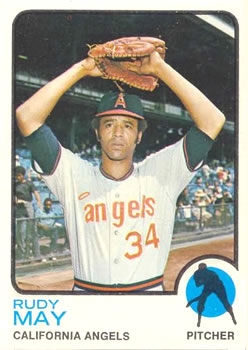

May, a 6-foot-2, 205-pound lefty, started 360 of his 535 appearances across 16 seasons (1965, 1969-1983). He compiled a 152-156 record and 3.46 ERA with the Angels, Yankees, Orioles, and Expos. He finished among the American League’s top 10 in strikeouts per nine innings seven times and led the league with a 2.46 ERA in 1980.

On July 18, 1944, Rudolph “Rudy” May Jr. was born to Rudolph and Oletha (Rowe) May in Coffeyville, Kansas. The elder Rudolph was a Chief Boatswain’s Mate in the Navy. When World War II ended, the family moved to Oakland, California, where Rudy’s brothers Donald and Leon were born. According to the 1950 census, their father was a high lift operator at the Naval Field Annex.

As a kid, Rudy watched his father catch for a Navy ballclub. “He had all the equipment in the car, and when he wasn’t watching, I used to go and play with it,” May said.2 The major-league Giants moved to San Francisco when May was 13. Before that, he attended Triple-A Pacific Coast League (PCL) games at Seals Stadium. Spectators could watch batting practice for free, but May would wait outside until the police cleared the stands of non-ticket holders. Then, he recalled, “I’d hop the fence and hide in the men’s room until the game started.”3

One of May’s neighborhood friends was future Hall of Famer Joe Morgan. “Joe and I played all through high school together; junior high school, elementary school, we played basketball, we did it all,” May said.4

That included football, which had an unusual effect on his pitching. At Castlemont High School, May was an all-Oakland Athletic League offensive end as a junior and senior.5 “I broke both wrists on one play,” he recalled, explaining that he couldn’t fully bend his pitching wrist afterwards. “So I throw a curve with both my wrist and elbow.”6

As a junior, May’s 6-2 record earned him All-City honors.7 But his father prohibited him from pitching as a senior since he had a chance for a college scholarship if he could improve his grades. “Both my parents worked so they didn’t know I kept playing baseball,” May said.8 In spring 1962, he threw a no-hitter, a one-hitter, and compiled a string of 29 1/3 consecutive scoreless innings with 65 strikeouts and only five hits allowed. Scouts from at least eight major-league teams noticed, and Castlemont coach Hal Seifer said, “I think Rudy has all the equipment”9

But May’s father, who had reached adulthood before the major leagues desegregated, was skeptical. “My dad used to say, ‘Blacks don’t be ballplayers,’” May recalled. “He didn’t want me to be hurt if I didn’t make it to the top”10 Once, the elder Rudolph caught a few of his son’s pitches and pronounced, “He’s got nothing.” When Rudy told his mother that he’d held back to avoid hurting his dad, she challenged him to let loose if he wanted permission to pitch. One of his next deliveries knocked his father over.11 By season’s end, local writers voted May the East Bay’s best baseball player.12

Between high school and American Legion competition in 1962, May went 12-1 with a 0.59 ERA.13 In one outing, he whiffed 22 batters.14 May was attending the University of San Francisco on a sports scholarship when Minnesota Twins scout Bob Thurman15 signed him to a professional contract for $8,000 on November 5, 1962.16

Prior to spring training in Fernandina Beach, Florida, most of May’s experience with racial discrimination came from listening to his parents. However, only Minnesota’s white players could stay at the team hotel, while African Americans had to lodge with local families. In the Twins’ clubhouse, players of color had to drink from a bucket instead of the fountain. Unfamiliar with such customs, May recalled, “I got into a little bit of trouble because I was the only black player from the West Coast.”17

Instead of one of Minnesota’s more advanced, Southern-based affiliates, May was assigned to the Bismarck-Mandan (North Dakota) Pards of the Class A Northern League in 1963. His 120 walks and 25 wild pitches in 168 innings led the circuit, but he went 11-11 (4.29 ERA) to earn All-Star recognition.18

That fall, the Chicago White Sox acquired May in the first-year player draft for $8,000.19 Chicago GM Ed Short said that three separate scouts had recommended him.20 The White Sox would lead the AL in ERA for the second straight year in 1964. When spring training ended, Chicago had so many pitchers that, as May recalled, “They sold my contract outright to their Triple-A team which meant they could no longer protect me.”21

May began 1964 in the Class A Carolina League. Through May 16, his record for the Tidewater (Virginia) Tides was 7-0 (1.35), with two 16-strikeout games.2223 On June 2, he fanned 18 batters, including a circuit-record nine in a row.24 May earned a promotion to the Triple-A PCL, where he went 4-2 (2.77) in 10 starts for the Indianapolis Indians before he was informed that his season was over. The White Sox wanted to hide him from scouts since they couldn’t protect him in the upcoming Rule 5 draft.25

Aware that they would likely lose May anyway, the White Sox traded him to the Philadelphia Phillies for catcher Bill Heath and a player to be named later (pitcher Joel Gibson) on October 15. The Phillies then sent May and slugging prospect Costen Shockley to the Los Angeles Angels for southpaw Bo Belinsky at the winter meetings. Scout Tufie Hashem had watched May for two weeks at Indianapolis and explained, “I told [Angels GM] Fred [Haney to take the Phillies offer.”26

In spring training 1965, May said, “I’d rather stay here [with the Angels] than go to the minors. I can learn simply by talking to guys like Fred Newman, Dean Chance and Joe Adcock.” During exhibition play, May impressed L.A. manager Bill Rigney, who observed, “His best asset is motion. It’s murder finding the ball.”27 May made the Opening Day roster, slated for spot duty.

Chance developed a blister, so May debuted by starting the fifth game of the season, against the Detroit Tigers at Dodger Stadium on April 18, 1965. Through seven innings, he had a 1-0 lead and a no-hitter going. But Jake Wood broke it up with a pinch-hit, one-out double in the eighth that Angels center fielder José Cardenal dove for but couldn’t corral.28 The Tigers tied the game on an unearned run before the Angels prevailed in the 13th. May received a no-decision for nine innings of one-hit, 10-strikeout work.

Although May lost his next outing, it was a 1-0 decision at Yankee Stadium on a fourth inning Mickey Mantle homer. May beat the Kansas City Athletics in his next two starts, but a four-game losing streak followed. After he shut out the Baltimore Orioles on June 6 to earn his first win in a month, May said, “I never pitched a game before without walking anyone. Give the credit to [pitching coach] Marv Grissom. He shortened my stride and pointed my shoulder right at that hitter and made me follow through. It not only cured my control but put better stuff on my fastball.”29 May won only once more, however, finishing his rookie season with a 4-9 (3.92) record in 30 appearances (19 starts).

On January 13, 1966, May married Eleanora Greene, the soprano voice of the soul group The Superbs. (Angels outfielder Leon Wagner had introduced them.30) Before the couple divorced in 1972, they had two daughters: Monique Antoinette and Edith Louise.31

May spent most of the 1965-66 offseason serving a six-month army commitment.32 The Angels were moving to the Los Angeles suburb of Anaheim, so during spring training, May and Cardenal visited a 131-unit apartment complex in Orange County advertised on a locker room bulletin board. But the manager of the complex discouraged them, suggesting that they share a back unit, where they would be less visible. When news of the players’ mistreatment reached the papers, the Anaheim Chamber of Commerce apologized, and hundreds of other housing offers poured in.33

But May was optioned to the PCL’s Seattle Angels shortly before Opening Day. After seven appearances, his ERA was 5.10. He had fallen off the mound throwing a sidearm pitch, wrenched his left side, and torn ligaments in his throwing shoulder.34 “I was sling-shotting the ball,” he explained. “Marv Grissom told me it would happen. And it did.”35

The Angels sent May to the Double-A Texas League, but he made only two appearances for the El Paso Sun Kings. Overall, he logged just 35 innings all season. “Just when it looked like I’d never pitch again, the doctors found my blood was too thick,” he said. “That’s what was causing the inflammation. They started giving me shots, put me on a diet, and I had to drink two and a half gallons of water every day.”36

In 1967, May’s arm still ached, and as a result he spent the season with the San Jose Bees in the Class A California League, where he went 7-2 (3.11) in 14 games (12 starts). With his baseball future in doubt, he enrolled in a commercial diving school. “My arm wasn’t sound anymore,” he explained. “The diving wasn’t a sport anymore. It was a livelihood.”37

May spent his third straight season in the minors in 1968 and got off to a 2-7 start for El Paso. Then he won his last six regular season decisions. “He became the best pitcher in the Texas League,” remarked Sun Kings manager Chuck Tanner. “He was awesome. He was overpowering.”38 May won Game One of the playoffs to help El Paso claim the championship.39

“It all came back in the middle of ’68… My arm, my shoulder, my confidence,” May said.40 “I got tired of babying it… I had to rear back and fire. If the arm fell off, it fell off. I had to find out.”41

That fall in the Arizona Instructional League, May went 6-2 (1.15). “I think now that the sore arm was a blessing,” he said. “I had to fall back on finesse. I was forced to learn control. It completed my education.”42 May credited Tom Morgan, the Angels’ minor-league pitching coach, saying, “He’s given me two kinds of fastballs – including one that rises… My biggest adjustment has been to break my hands above my knee. I had been bringing them back to my hip.”43

May opened the 1969 season with the Angels and, in April, won his first big-league game in nearly four years. He lost his next six decisions, though, and moved to the bullpen when Lefty Phillips replaced Rigney as manager. May returned to the rotation in the second half and wound up 10-13 (3.44) for a 71-91 club with the AL’s lowest-scoring offense.

The Angels improved to 86-76 in 1970. When May shut out the A’s in Oakland on August 3, he was 6-7 with a 3.26 ERA. But he went 0-6 (5.95) over his next dozen starts and wound up 7-13, dropping his career winning percentage to .375. “People were beginning to say, ‘That Rudy May, he’s a great pitcher. Why doesn’t he win?’” May acknowledged.44 “I used to hang curves when the other team got players on base. I didn’t know why.”45

May and his wife made a decision. “Confidence is 50 percent of pitching so we decided I would go to a psychiatrist to find out why I had trouble,” he said46 The psychiatrist suggested chewing gum while he pitched as a good way to ease tension.47 May tried it. Years later, after a photographer captured him blowing a large bubble, he convinced Topps Chewing Gum, Inc. to send him free supplies.48

May won three of his first four decisions in 1971, but his record had slid to 3-4 when he tripped at home and suffered a hairline fracture of his wrist.49 Following nearly four weeks on the disabled list, he wound up 11-12 (3.02) for a sub-.500 Angels club. Twice he struck out 13 batters in one contest, and he hurled 12 shutout innings in a no-decision at Oakland. By allowing only 12 homers and 160 hits in 208 1/3 innings, May posted the third-stingiest rate per nine innings in each category among AL ERA-title qualifiers.

In 1972, May’s record was 2-7 by mid-July. The Angels had scored a total of six runs in his defeats. A season ticket holder gifted him a horseshoe that had belonged to Seabiscuit, the 1938 American Horse of the Year, to change his luck.50 May hung it by his locker and came back to post his first winning record in the big leagues (12-11), lower his ERA to 2.94, and strike out 169 batters – his best single-season total in the majors. On August 10, he fanned a career-high 16 in a victory over the Twins.

May was nicknamed “the Dude” because of his sharp-dressing ways.51 Superstitious, he positioned the resin bag in the same spot and wouldn’t step on the foul lines on his way to the mound. He ate up to 10 bags of salted sunflower seeds per game on the bench.52

Following a fifth-place finish, California hired Bobby Winkles to manage in 1973. When May started on June 26, the Angels were in first place and his record was 6-6, including shutouts for each of his first four victories. But back pain forced him to exit early, and he wound up in traction for a pinched sciatic nerve. May came back two weeks later but lost 11 of his last 12 decisions to finish with a 7-17 mark.

With rookie southpaw Frank Tanana joining California’s rotation, May was told that he might not make the team during 1974 spring training.53 As it happened, he began the season in the bullpen amidst constant trade rumors. His personal losing streak extended to nine when he lost his only start before June. “[Winkles] just didn’t have confidence in me and so I lost it in myself,” May said later.54

May was California’s longest-tenured player, but he yearned for a change of scenery, according to beat writer Dick Miller, who described him as “a many-time finalist in the Good Guy category.”55 On June 15, 1974, a few hours before the trading deadline, May was sold to the New York Yankees for a reported $100,000.56

He pitched complete games in his first three appearances for the Yankees. In his fourth outing, however, May leaped for a high hopper in Kansas City, lost his balance, and wound up on the disabled list with a bruised shoulder and a sprained hip.57 He returned three weeks later and finished 8-4 (2.28) for New York. In 114 1/3 innings with his new team, he notched 90 strikeouts and allowed only 75 hits.

In 1975, May completed 13 starts – a personal best – and went 14-12 (3.06). No AL starter was tougher to take deep that season, as he surrendered only nine homers in 212 innings. The Sporting News observed that May had altered his motion to better jam right-handers with his fastball and started gripping his changeup with two fingers instead of three.58 The following year, the same publication noted that he had evolved from a “flame-thrower” into a “crafty” southpaw with a “sharp-breaking curve.”59 “People feared it. It was that devastating,” said May about his bender after retiring. While it was largely self-taught, he credited Yankees pitching coach Whitey Ford for showing him “the motion and what I needed to do at the end of the pitch to get the most out of it.”60

Billy Martin replaced Bill Virdon as the Yankees manager in August 1975, and May’s relationship with the new skipper was difficult. In May’s third start of 1976, he carried a no-hitter and a 1-0 lead into the bottom of the ninth inning at Royals Stadium. But after Amos Otis led off with double, May was taken out, and New York wound up losing in the 11th. After May failed to complete any of his first eight starts, Martin told him that he would never pitch for him again and threw a ball at him for emphasis.61 As it happened, another pitcher’s illness caused May to get the ball on two days’ rest on May 30, and he shut out the Tigers in Detroit.62 May kept starting, but tensions with Martin worsened. Years later, May described an encounter with the drunken skipper at a bar as “a big hassle” that left him “psychologically beat.” 63

On June 15, May learned that he had been traded to the Orioles as part of a 10-player blockbuster deal. The news came from teammate Catfish Hunter, whom Martin sent as messenger.64 All five players that New York received became former Yankees within two years, while three of Baltimore’s five acquisitions – Rick Dempsey, Scott McGregor and Tippy Martinez – wound up in the Orioles’ team Hall of Fame.

In 21 starts for Baltimore, May went 11-7 to finish 1976 with an overall record of 15-10 (3.72). Three of his victories came against the Yankees, and he defeated rookie sensation Mark Fidrych, 1-0, in Detroit.

May’s National Association of Underwater Instructors license allowed him to moonlight as a diver during off-seasons. Following his first year with New York, for example, he helped lay an oil pipeline off the coast of Long Island. Once, he teamed up with one-time Angels teammate Bill Singer to raise a sunken boat.65 “I wasn’t making any money in baseball but I was making $400 per hour diving,” May explained. “It really supplemented my baseball income.”66

But May’s diving concerned the Orioles, so the three-year, $500,000 contract67 that he signed prior to Opening Day 1977 included a clause prohibiting hazardous professional duty.68 That season, in a career-high 37 starts and 251 2/3 innings, May went 18-14 (3.61) to achieve his personal best in victories.

After the 1977 season, two 23-year-olds – McGregor and Dennis Martínez – were ready to move into Baltimore’s rotation. That made the 33-year-old May expendable. On December 7 the Orioles traded May and minor-league righties Bryn Smith and Randy Miller to the Montreal Expos for rookie outfielder Gary Roenicke and veteran relievers Don Stanhouse and Joe Kerrigan on December 7. “I love it,” said Montreal manager Dick Williams, a former Red Sox and A’s skipper.69 “When he was with California, Rudy gave us nothing but trouble.”70

May went 6-5 with a 3.36 ERA in his first 13 starts for the Expos in 1978. Over the next month and a half, however, he lost four straight decisions, went to the bullpen briefly, and pitched more than five innings in just one of six starts. Then he spent six weeks on the disabled list with a sprained ankle.71

That winter, Montreal traded for veteran starter Bill Lee, a southpaw who had worn out his welcome in Boston. The Expos rotation candidates already included All-Star Steve Rogers, 20-game winner Ross Grimsley, and impressive 1978 rookies Scott Sanderson and Dan Schatzeder. May began 1979 in the bullpen and remained there for all but seven of his 33 appearances. “It’s too late in my career for me to worry about personal statistics,” he said. “What I want to do is be with a winner.”72 The Expos won 95 games (a single-season high for the franchise in Montreal) and led the NL East as late as the season’s final week.73 May was a major contributor, posting a 10-3 (2.31) record over 93 2/3 innings.

After the season, May became a free agent. “One day I ran into Rudy at the Tampa airport,” reported Yankees owner George Steinbrenner. “I told him, ‘I’m going to get you back.’”74 On November 8, 1979, May signed a three-year deal to return to New York for $250,000 annually, plus a $250,000 signing bonus.75 “I needed security for my family. I wanted to play at home [California]. I wanted to be on a contending team. I satisfied two of my priorities,” he said.76

During spring training 1980, May’s chronic back problems flared up. He began the season on the disabled list, joined the active roster in the final week of April, and made his first 19 appearances in relief. From June 27 through the end of the season, though, he started 17 of his 22 outings. Overall, May went 15-5 and led the American League in ERA (2.46) and WHIP (1.044). With 133 strikeouts against just 39 walks, his 3.41 strikeout-to-walk ratio also paced the league.

The Yankees won the AL East with a 103-59 record. After New York lost the first game of the ALCS in Kansas City, May matched up against three-time 20-game winner Dennis Leonard in Game Two at Royals Stadium. He went the distance and allowed only six hits, but four of them came in succession in the third inning, when the Royals scored three runs. The Yankees lost, 3-2, and May was charged with his first defeat since July 22. New York was eliminated the following evening.

During the strike-shortened 1981 season, May led the Yankees in starts and innings pitched, but his record was just 6-11. New York won the AL East in the first half of the split season, and May worked once out of the bullpen in the Yankees’ Division Series victory over the Milwaukee Brewers. New York beat Oakland in the ALCS, with May starting once and receiving a no-decision. In the World Series against the Los Angeles Dodgers, May relieved three times and compiled a 2.84 ERA over 6 1/3 innings, but the Yankees lost in six games.

Early in the 1982 season, May saw little action until moving into the rotation in early May. On May 26, he partially tore his left pectoralis major in a start against the Blue Jays.77 He missed a month and worked sparingly out of the bullpen after returning. During the final road trip of the first half, the Yankees wanted him to accept an assignment to Triple-A Columbus, which May planned to refuse. “I figured my Yankee career had reached an end,” he said. “The people upstairs looked at my age and decided I was too old to pitch.”78 On July 6, though – 12 days before his 38th birthday – May tossed three hitless frames to earn a 12-inning victory over Seattle. The Yankees demoted rookie infielder Andre Robertson instead.79 New York finished with a losing record but May posted a 2.89 ERA in 41 appearances (six starts). In 106 innings, he issued only nine unintentional walks.

During the 1982-83 offseason, the White Sox selected May as compensation for the Yankees’ signing of free agent Steve Kemp. May’s contract had expired, but his agent, Dick Moss, successfully argued that his no-trade clause was still in effect.80 (May had previously exercised it to nix a swap to the Royals for Hal McRae prior to the 1982 season.81) Shortly thereafter, May agreed to a two-year deal worth $1.375 million with New York.82 “I don’t know if I was an ex-Yankee or not, but it feels good to be back,” he remarked.83

When The Sporting News polled his peers in 1983 spring training, May was one of 25 AL pitchers accused of doctoring the ball.84 If that was the case, it didn’t help him that year, as he relieved only 15 times, going 1-5 (6.87) around nearly three months on the disabled list with back problems.85 In spring training 1984, he announced that he would retire after one more season.86 May was a longshot to make New York’s roster, however. Two weeks before Opening Day, his back woes landed him on the DL again, and he remained there all season.87 He finished his major-league career with 1,760 strikeouts in 2,622 innings pitched.

After baseball, a friend in Fresno, California, introduced May to the convenience store business. Before long, May was managing three stores and moved up the corporate ladder to a marketing consultancy position. In 1993, he joined British Petroleum as a Franchise Business Consultant and remained there until his 2014 retirement. Later that year, he told an interviewer, “At this point, I take more pride in my fishing accomplishments than anything I did in baseball.”88

As of 2022, May resided in Hertford, North Carolina, with his wife Marion (Jones).

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and David Bilmes and fact-checked by Tim Herlich.

Sources

In addition to sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted www.ancestry.com, www.baseball-reference.com and www.retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 Phil Pepe, “Mom Has Some Winning Advice for Rudy May,” Daily News (New York, New York), April 16, 1981: 100.

2 Jeff Pearlman, “The Quaz: Rudy May,” January 9, 2014, https://jeffpearlman.com/2014/01/09/the-quaz-qa-rudy-may/ (last accessed May 31, 2021).

3 Phil Pepe, “Yanks Hear Mellow Music from Ex-Angel Rudy,” The Sporting News, July 13, 1974: 7.

4 Paul Francis Sullivan, “The Rudy May Interviews Part 3,” Sully Baseball, February 11, 2014, https://sullybaseball.wordpress.com/2014/02/11/the-rudy-may-interviews/ (last accessed May 31, 2021).

5 Rudy May, Publicity Questionnaire for William J. Weiss, April 8, 1963.

6 Frank Gianelli, “Tips by Morgan Bring Out Best in Hurler May,” The Sporting News, November 23, 1968: 54.

7 John Simmonds, “Rudy May on Brink of Fame?” Oakland Tribune, May 15, 1962: 42.

8 Pearlman, “The Quaz: Rudy May.”

9 Simmonds, “Rudy May on Brink of Fame?”

10 Ian MacDonald, “Rudy May: Scuba Diver at Heart,” Montreal Gazette, May 9, 1978: 26.

11 Pearlman, “The Quaz: Rudy May.”

12 “Sunset High Star Wins Best Prep Award,” Oakland Tribune, June 5, 1962: 41.

13 “Twins Sign Rudy May,” Oakland Tribune, November 13, 1962: 32.

14 “Win Moves Erwins into Tie for Lead,” Oakland Tribune, July 9, 1962: 36.

15 Rudy May, Publicity Questionnaire for William J. Weiss, February 12, 1965.

16 MacDonald, “Rudy May: Scuba Diver at Heart.”

17 Pearlman, “The Quaz: Rudy May.”

18 “Five Dukes on Star Team,” The Sporting News, July 20, 1963: 45.

19 “Major Draft Picks,” The Sporting News, December 14, 1963: 9.

20 Jerome Holtzman, “Moss’ Report Spurs Chisox to Nab Estevis,” The Sporting News, December 14, 1963: 19.

21 Sullivan, “The Rudy May Interviews Part 2.”

22 “Rudy May Wins Seventh,” The Sporting News, May 30, 1964: 41.

23 Larry Bonko, “Draft of Rudy May Proving $8,000 Bargain for Chisox,” The Sporting News, May 23, 1964: 43.

24 Larry Bonko, “20-Win Candidate May Fights Down Ulcers, Mows Down Hitters,” The Sporting News, July 25, 1964: 41. May’s 1970 Topps baseball card specifies that his record-setting 18-strikeout effort occurred on June 2.

25 Sullivan, “The Rudy May Interviews Part 2.”

26 Ross Newhan, “May Day Came Early for Rudy, Angel Hill Find,” The Sporting News, May 1, 1965: 21.

27 Ross Newhan, “Sleeper May Gives Angels a Real Eyeful,” The Sporting News, April 24, 1965: 27.

28 Murray Chass “Last Minute Pitching Selection Results in Top Effort by Rudy May,” Herald (Jasper, Indiana), April 19, 1965: 9.

29 Ross Newhan, “‘We’ve Bluffed Our Way So Far,’ Rigney Admits,” Independent (Long Beach, California), June 7, 1965: 25.

30 John Wiebusch, “No Maybes for the Rudy Mays,” Los Angeles Times, March 1, 1970: C5.

31 Rudy May, Angels Publicity Questionnaire (accessed through ancestry.com).

32 MacDonald, “Rudy May: Scuba Diver at Heart.”

33 Ross Newhan, “May, Cardenal Get 100 Housing Offers in Wake of Rebuffs,” The Sporting News, March 26, 1966: 6.

34 Frank Gianelli, “Tips by Morgan Bring Out Best in Hurler May,” The Sporting News, November 23, 1968: 54.

35 John Wiebusch, “All the Way Back – May’s Tough Climb,” The Sporting News, August 30, 1969: 18.

36 John Hall, “May Coming Up Fast in February,” Los Angeles Times, February 20, 1967: C6.

37 MacDonald, “Rudy May: Scuba Diver at Heart.”

38 Ross Newhan, “Angels’ May Searches for Road to Anaheim,” Los Angeles Times, March 7, 1969: D1.

39 “Texas League,” The Sporting News, September 21, 1968: 37.

40 Wiebusch, “No Maybes for the Rudy Mays.”

41 Newhan, “Angels’ May Searches for Road to Anaheim.”

42 Newhan, “Angels’ May Searches for Road to Anaheim.”

43 Gianelli, “Tips by Morgan Bring Out Best in Hurler May.”

44 “Rudy May Gets His Confidence Back on the Mound,” Redlands (California) Daily Facts, May 4, 1971: 9.

45 Dick Miller, “Psychiatrist Gets Assist for May’s Revival on Mound,” The Sporting News, August 7, 1971: 24.

46 Miller, “Psychiatrist Gets Assist for May’s Revival on Mound.”

47 “Major Flashes,” The Sporting News, August 28, 1971: 33.

48 Pete Boal, “Rudy May Hopes to Add Winning to List of Habits,” San Bernardino County (California) Sun, March 11, 1973: 59.

49 “Angel Notebook,” The Sporting News, June 12, 1971: 8.

50 Dick Miller, “Angel Notebook,” The Sporting News, June 24, 1972: 18.

51 Dick Miller, “Dr. Strange Moves’ Label Pinned on Angel Manager,” The Sporting News, August 25, 1973: 18.

52 Boal, “Rudy May Hopes to Add Winning to List of Habits.”

53 Phil Pepe, “Yanks Hear Mellow Music from Ex-Angel Rudy,” The Sporting News, July 13, 1974: 7.

54 “Rudy May Discovers New Life,” Progress Bulletin (Pomona, California), June 24, 1974: 10.

55 Dick Miller, “Here They Are…Angel Prize Winners,” The Sporting News, November 9, 1974: 46.

56 Dick Miller, “Angels’ Notebook,” The Sporting News, July 6, 1974: 9.

57 “Sports News in Brief,” Progress Bulletin, July 13, 1974: 10.

58 “May Finds Formula,” The Sporting News, July 26, 1975: 28.

59 Phil Pepe, “The Dude Dresses Up Yankee Hurling,” The Sporting News, June 19, 1976: 12.

60 Pearlman, “The Quaz: Rudy May.”

61 Pearlman, “The Quaz: Rudy May.”

62 Red Foley, “Rudy 4-Hits Tame Tigers, 4-0, as White (3-Run), Munson HR,” Daily News, May 31, 1976: 32.

63 Pearlman, “The Quaz: Rudy May.”

64 Pearlman, “The Quaz: Rudy May.”

65 John Bruns, “Who Would Have Thought May Would be Yank Ace?” Home News (New Brunswick, New Jersey), June 15, 1975: 23.

66 Pearlman, “The Quaz: Rudy May.”

67 Dick Young, “Clubhouse Confidential,” Daily News, April 3, 1977: 86.

68 MacDonald, “Rudy May: Scuba Diver at Heart.”

69 Ian MacDonald, “May – and Grimsley – Warm Expos in December,” The Sporting News, December 24, 1977: 57.

70 Ian MacDonald, “Williams Goes ‘Whoops’ as Expo Park Guide,” The Sporting News, February 25, 1978: 53.

71 Ken Nigro, “Oriole Notes,” Baltimore Sun, July 22, 1978: B5.

72 Ian MacDonald, “Forgotten Man May Rescues Expos,” The Sporting News, August 11, 1979: 16.

73 After the Expos relocated, the Washington Nationals won 98 games in 2012 to set a new franchise record.

74 Phil Pepe, “May Passes Bullpen Test,” The Sporting News, May 31, 1980: 12.

75 “Free Agent Swag,” The Sporting News, March 8, 1980: 33.

76 Phil Pepe, “Watson, May Give Yanks ‘Early Flag,’” The Sporting News, November 24, 1979: 52.

77 Jane Gross, “Reds Beat Mets; Yanks Lose, 4-3,” New York Times, June 5, 1982: 17.

78 Moss Klein, “A Reprieve for May Bolsters Yankees,” The Sporting News, August 8, 1982: 23.

79 “Transactions,” New York Times, July 9, 1982: A18.

80 Tracy Ringolsby, “No-Trade Clauses Create Contract Woes,” The Sporting News, January 31, 1983: 43.

81 Mike McKenzie, “Royals’ Best-Laid Plans Fall Apart,” The Sporting News, January 2, 1982: 46.

82 Murray Chass, “Fernando’s $1 Million Tops Pay Awards,” The Sporting News, March 7, 1983: 60.

83 Moss Klein, “Yanks Get Lucky; May’s Happy, Too,” The Sporting News, February 7, 1983: 36.

84 “The Doctors,” The Sporting News, April 4, 1983: 20.

85 Moss Klein, “Murcer Switches to Video Booth,” The Sporting News, July 4, 1983: 16.

86 Barry Levine, “Yanks’ May Hoping to Make it in 21st – and Final – Year,” Home News (New Brunswick, New Jersey), March 11, 1984: E1.

87 Bill Madden, “May’s Career Over?” Daily News, March 20, 1984: 60.

88 Pearlman, “The Quaz: Rudy May.”

Full Name

Rudolph May

Born

July 18, 1944 at Coffeyville, KS (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.