Ted Strong

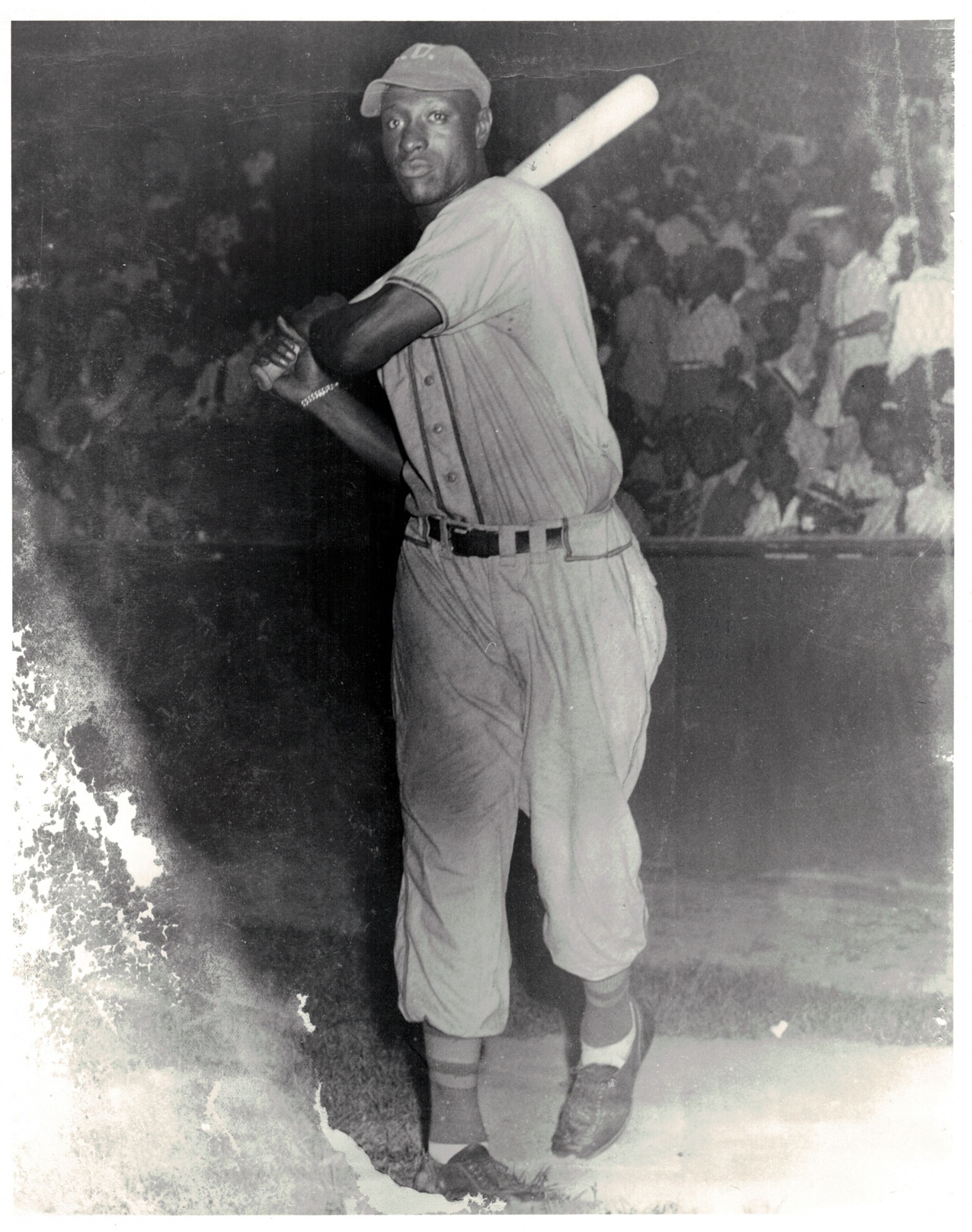

Ted Strong Jr. thrilled baseball fans with a hard-hitting swing that he displayed over his 10 seasons in the Negro Leagues and in Mexico. The tall, muscular Strong played in seven All-Star games as a member of the Kansas City Monarchs and other teams. This two-sport superstar also toured the country as a member of the Harlem Globetrotters basketball squad.

Ted Strong Jr. thrilled baseball fans with a hard-hitting swing that he displayed over his 10 seasons in the Negro Leagues and in Mexico. The tall, muscular Strong played in seven All-Star games as a member of the Kansas City Monarchs and other teams. This two-sport superstar also toured the country as a member of the Harlem Globetrotters basketball squad.

Strong batted .321 with 40 home runs in 1,285 at-bats over his career. He posted a .406 on-base percentage and a .518 slugging percentage.1 No less an authority than Cum Posey marveled at Strong’s talents. Posey, who had played ball and managed and was the principal owner of the Homestead Grays, called Strong “the best young player of Negro baseball” in 1937.2

Strong never got the chance to compete against White major-league baseball teams and to take his swings against Bob Feller, Dizzy Dean, or the other top big-league pitchers from that time. In a Chicago Tribune article, Strong’s biographer, Sherman L. Jenkins, called that a source of “frustration and disappointment” for the player.3 Jenkins remembered Buck O’Neil praising Strong as “the best athlete he had ever seen.”4

Theodore Relighn Strong Jr. was born on January 2, 1917, in South Bend, Indiana, an industrial/college city located on the Saint Joseph River. He was the eldest child of Theodore Strong Sr. and Vera Leona Smith. In June the young family, which eventually consisted of 13 children, moved to Chicago.

Strong Sr., a former lightweight boxer, liked to describe his first-born son as “big for his age.”5 The youngster excelled at baseball and basketball at Wendell Phillips High School in Chicago. Even as a freshman, “his muscular six-foot-two-inch frame made him standout among his peers,” Jenkins wrote.6 Soon enough, he attracted the attention of a 5-foot-3-inch basketball fanatic.

Abe Saperstein had moved with his family from London, England, to Chicago in 1907 when he was 5 years old. The so-called Windy City was “a swirl of constant motion.”7 Saperstein, who loved sports, thrived in the fast pace and founded the Trotters in 1928. (Saperstein later added “Harlem” to the Trotters brand as a salute to the largely African American section of New York City.) Almost from the start, the Globetrotters melded great basketball with a touch of comedy. One writer commented after a game, “The crowd was in an uproar during the last three quarters at the antics and clowning the Trotters mixed with their stellar playing.”8

Strong began his Globetrotter career in 1936. He had grown a few inches over the past few years. Various sources list Strong’s ultimate height at anywhere from nearly 6-foot-4 to about 6-foot-6, or even taller. He also played his rookie season in the Negro Leagues that year. Strong batted a meager .167 as a shortstop for the American Giants.

The next year, though, he earned a spot in the fifth annual East-West All-Star Game, played at Comiskey Park in Chicago. The East won, 7-2, thanks in part to fielding miscues committed by Strong and other West players. Strong singled home a run and drove another pitch that bounced off the center-field wall and eluded outfield defenders long enough for him to secure an inside-the-park home run. “Strong rounded third like a big locomotive being waved on home by (third-base coach) ‘Candy Jim’ Taylor,’” said the Chicago Defender.9 Strong played for the American Giants, the Indianapolis Athletics, and the Kansas City Monarchs in 1937. He batted .359 with 3 home runs and 31 RBIs.

Strong returned to Indianapolis in 1938, as a member of the ABCs, and once again earned an All-Star berth. More than 30,000 fans watched the action at Comiskey Park after Chicago Mayor Edward J. Kelly threw out the first pitch. Strong went hitless in three at-bats but walked and scored a run as the West won, 5-4. The African American press corps argued that the top Negro League players were just as good as major leaguers. It was asserted that players like Buck Leonard, Willie Wells, Ray Dandridge, and Josh Gibson “would make it tough sledding for their big-league opponents.”10

Many in the White press still offered only grudging respect for the Negro Leagues. In an article titled “How Good Is Negro Baseball?” Lloyd Lewis of the Chicago News wrote on August 22, 1938, that although “Negro professional baseball … is faster on the bases than major league ball now played in the American and National circuits” and “is almost as swift and spectacular on the field, it lacks the batting forms of the white man’s big leagues.”11 Lewis took a few shots at Strong, “the tall, magnificently proportioned first baseman[,]” as he criticized him for “showboating with his glove.”12 For the second straight year, Strong also saw action with the Monarchs and he hit for a combined .373 average with Indianapolis and Kansas City.

Strong played the entire 1939 season with the Monarchs. For the young ballplayer, Jenkins wrote, “it was probably a dream come true” as the Monarchs were “beginning to blossom as a standout team in the Negro Leagues.”13 J.L. Wilkinson, an Iowa native and a solid semipro pitcher during his playing days, had founded the club in 1920. Years earlier, he had put together a squad called the All-Nations team for which he hired Whites, Blacks, Asians, Native Americans, and Polynesians to play ball. Wilkinson and Kansas City businessman Thomas “T.Y.” Baird, both White men, attended an organizational meeting of the Negro National League, held at the Paseo YMCA in Kansas City on February 13, 1920, and applied for membership. Rube Foster, owner of the Chicago American Giants, hesitated to accept a White owner into the league, “but he relented because of Wilkinson’s reputation for integrity and fairness.”14 Wilkinson “built the Monarchs into the most successful NNL club of the 1920s.”15 (The Monarchs competed in the Negro National League through 1931 and as an independent club from 1932 to 1936. Kansas City joined the Negro American League in 1937.)

In 1939 the outstanding Monarchs roster included hitters such as first baseman O’Neil, second baseman Newt Allen, left fielder Willard Brown, and center fielder Turkey Stearnes while the pitching staff was led by future Hall of Famer Hilton Smith. Strong and O’Neil became good friends. O’Neil described Strong, with some exaggeration, as “near seven-feet tall” and claimed that “[t]hey put him at short because he had great hands and rifle arm.”16 Strong hit .304 with 3 homers and 30 RBIs in 53 games as the Monarchs finished 42-25 and won the franchise’s sixth league title.

Strong also married during this time. Records indicate that he and Ruth Jackson took out a marriage application in Jackson County, Missouri, on September 2, 1939. Strong jumped to the Mexican League and the La Junta de Nuevo Laredo squad in 1940. He batted .332 with a team-high 11 home runs. According to at least one observer, Strong “proved to be the best third baseman in the circuit.”17

At the conclusion of every baseball season, Strong rejoined the Globetrotters, who were easily one of the best basketball teams in the country. In their first 14 seasons, the squad won 2,022 of 2,164 games.18 Strong was certainly an important part of that success. The Ogden (Utah) Standard-Examiner noted, “This chap Ted Strong has the largest hands in the game. He is the only man who can catch and snatch the ball in mid-air with the fingers of one hand. It’s one of the miracles of the sport to see Strong catch a pass or stop a dribble in this manner.”19

Strong also took part in some of the team’s trademark comedic antics. During one game, he “drew gales of laughter with his moans of ‘foul, foul.’”20 Strong played center and was eventually named captain of the Globetrotters. In 1940 Saperstein’s squad beat George Halas’s Chicago Bruins to capture the World’s Basketball Championship. A childhood friend of Strong’s recalled, “We were so proud of them. We used to sneak up to Ted’s room and get his Globetrotters jacket and wear it around the neighborhood.”21

After his foray into Mexico in 1940, Strong returned to the Monarchs for the 1941 season. He batted .284 and helped Kansas City capture yet another league title. In 1942 Strong batted .364 and the Monarchs won the Negro League World Series. Kansas City swept the Homestead Grays in a best-of-seven series played at four different sites. (Griffith Stadium hosted Game One. The teams played Game Two at Forbes Field, Game Three at Yankee Stadium, and Game Four at Shibe Park.) Strong batted .316 in the Series and had an on-base percentage of .381. He scored a run in each of the games and hit a three-run homer in Game Three.

Strong still dreamed of playing in the major leagues. That dream took a step closer to reality when the Pittsburgh Pirates announced plans to hold tryouts for a select group of players after the 1942 season. Strong’s name was listed on a group of eight alternates. Those dreams were dashed when the Pirates announced just a few months later that the tryouts were canceled. The Chicago Defender told its readers, “The day will come when Negroes may get a tryout in the major leagues.”22

With World War II raging, Strong enlisted in the Navy on April 22, 1943. He entered as an apprentice seaman and trained for Seabee duty at the Great Lakes (Illinois) Naval Training Station.23 Strong later earned the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Ribbon, the Seabee insignia, and the Philippine Liberation ribbon. He also took part in capturing Majuro Atoll in the Marshall Islands and was granted his honorable discharge on January 20, 1946.24

While in Hawaii, Strong wrote a letter that offered advice to hopeful young Negro League ballplayers. “I started this letter for a purpose,” Strong began. “It’s about the young kids who are trying to fill the shoes of those who have gone to war. Naturally, at first, no one would expect those kids to perform like established stars, (but) all they needed was encouragement and time for them to find themselves.” Strong and some of his fellow Seabees rarely got a chance to play baseball while overseas. “Then when we did, brother, we thought we were some of the luckiest guys in the world by being able to play. And every chance we had, we did.”25

Strong added, “This war has taught me a lot and it had made me realize somewhere there’s someone who is worse off than yourself. And the sooner [American readers] understand that, the better off things will be in the future. … In the meantime, I say, lay off the [young ballplayers] and they won’t let you down. Someday, we’ll be back, maybe to play more ball, but you must admit new blood will be needed and this is the chance we probably needed to give COLORED baseball a new meaning to a new generation.”26

Once Strong returned stateside, he continued his career with both the Globetrotters and the Monarchs in 1946. He also indulged in life off the field and away from the court. He liked to hang out with his teammates and enjoy a few drinks, sometimes a few too many. “If truth be told,” Jenkins wrote, “Ted Jr. had started nipping at the rim of a shot glass early in his sports career.”27

Strong was now 29 years old. He batted .321 in his first season back with the Monarchs but failed to make the annual All-Star team. The Monarchs lost a thrilling seven-game World Series to the Newark Eagles that season. Six players from the two squads – Willard Brown, Leon Day, Larry Doby, Monte Irvin, Satchel Paige, and Hilton Smith, plus Eagles manager Biz Mackey – were later inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York.

The following season, as Strong suited up for the Monarchs, Jackie Robinson played his first game for the Brooklyn Dodgers. White baseball’s shameful color barrier finally had been broken. The Monarchs had signed Robinson in early 1945. With stars like Strong, O’Neil, and Hank Thompson off to war, Wilkinson needed ballplayers. Robinson, in turn, had already completed his military service and now needed a job. A friend had told him “there’s good money in black baseball,”28 so the former UCLA Bruin signed to play with Kansas City for $400 a month.

Robinson, a Georgia native, grew up in Southern California and was, like Strong, a standout multisport athlete. He had earned letters in football, basketball, and baseball at UCLA while also running track and playing tennis.

Some had thought Strong might be the White major leagues’ first Black player of the twentieth century. Baseball historian John Kovatch recalled talking to Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe about Strong. Radcliffe, born in Mobile, Alabama, in 1902, played for 15 teams in the Negro Leagues from 1928 through 1946. “(Radcliffe) said that Ted was one of the most talented athletes” in the Negro Leagues, Kovatch said. “He sounded like a good candidate to break the major league color barrier.” Kovatch lamented, “Radcliffe and a number of the older Negro League players felt that [Strong’s] drinking and carousing kept him from being the choice.”29

Strong turned 30 years old on January 2, 1947. By baseball standards, he was a grizzled veteran and “[t]hat kind of put him on the back burner.”30 Bob Kendrick, president of the Negro League Baseball Museum in Kansas City, agreed: “Ted was getting a little long in the tooth as well by the time they get to this point where they’re really considering breaking the color barrier.”31

In his biography of Strong, Jenkins added, “Ted Jr. wouldn’t have taken what Jackie Robinson took when he joined the Dodgers farm system and big-league teams. Yes, Ted Jr. played with the Globetrotters in all-white, small-town America for a number of years, but ‘an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth’ had been taught to him by Ted Sr.”32

Strong’s career with the Monarchs ended after the 1947 season. He batted just .210 (21-for-100) in 37 league games during his final campaign. Younger, faster, and – surprisingly – even bigger and stronger athletes looked to take his place. In 1948 Strong joined the Indianapolis Clowns, a squad that mixed serious action with comedy hijinks. Globetrotter Reece “Goose” Tatum also played for the Clowns. Born on May 3, 1921, in Arkansas, Tatum was the Trotters’ original Clown Prince. He stood 6-feet-4 and boasted an 84-inch wingspan.

Goose had started playing professional baseball in 1937 and had seen action with the Birmingham Black Barons prior to joining the Clowns during their time in Cincinnati. “Tatum was a decent hitter, spraying the ball to all fields,” according to Ben Green in his history of the Globetrotters. The ballplayer struggled in the field, however. “He played outfield, but his long arms seemed to interfere with his fielding and coordination.”33

Like Strong, Tatum enjoyed the nightlife. Neither player lasted long in Indianapolis. Although he batted .389 and drove in 10 runs, Strong played in only 12 games. Jenkins surmised, “Chances are they overstayed their welcome when they coupled their playing time with sampling the nightlife and having a good time.”34 Strong stayed with the Trotters through the 1949 season and then retired. Divorced from Ruth, he also remarried, this time to 22-year-old Florence Faulkner of Chicago.

Strong took a brief Hollywood turn in the early 1950s when he appeared in a movie about Saperstein’s basketball team. The Harlem Globetrotters opened in theaters on October 24, 1951. Produced by Columbia Pictures, the film stars Dorothy Dandridge and features Thomas Gomez as Saperstein. Jasper Strong recalled, “Oh, man, seeing my big brother on that big screen just made me so proud. No one else I knew in my neighborhood could say they had their brother in the movies.”35

In January of 1952, Strong began working as a clerk at a post office in Chicago, where he earned $1.66 an hour. In March, he was let go “due to absence from duty without leave.” Jenkins speculates that “marriage difficulties probably contributed to Ted Jr. only sporadically showing up for work.” Instead of going to work, Strong “would handle small assignments for Abe Saperstein.”36

Strong “slowly faded into the memory of the sports world as the years progressed.”37 He sometimes attended Globetrotter games played in the Chicago area and reminisced with old friends. His marriage to Florence ultimately ended in divorce.

Strong had developed emphysema, and his condition flared up on the afternoon of March 1, 1978, and it worsened throughout the day. He began to cough and struggled to catch his breath. Sensing trouble, a visitor to his house called for an ambulance. Strong died at 1:35 A.M. on March 2 at Provident Hospital on Chicago’s south side. He was 61 years old. Strong was “virtually penniless at the time of his death.”38 He was buried in an unmarked grave at Lincoln Cemetery in Blue Island, Illinois, a Chicago suburb.

Dave Condon briefly mentioned Strong’s passing in his column for the Chicago Tribune. The note had a few inaccuracies, including Strong’s age when he died and the length of his playing career with the Trotters. “Theodore ‘Ted’ Strong Jr., 62, who made sports history in 20 years with the Harlem Globe Trotters [sic] and as an infielder-outfielder for the Kansas City Monarchs and the Indianapolis A’s, died Friday.”39

The inspiration for Jenkins’ biography of Strong goes back to 1977. At that time, Jenkins wrote an article about Strong Sr.’s career in the Negro Leagues for a journalism class at Northern Illinois University. Decades later, he began to work on a book about Strong Jr. “After doing a little research, [Jenkins] realized the younger Strong had quite an extraordinary duo-sport career, and he would make an ever more fascinating subject than his father,”40said an article in the Aurora Beacon-News. In the preface to his biography of Strong, Jenkins wrote, “His full story needed to be told. … He is like the hundreds of African American men and women who played in the Negro Baseball Leagues and are unsung heroes.”41As to the absence of a plaque for Strong at the Hall of Fame, Jenkins said, “There was a little taint on his legacy,” referring to the ballplayer’s heavy drinking. “And it makes it hard to say, ‘OK, he should be in the Hall of Fame.’ But, heck, Ty Cobb and Babe Ruth drank. That’s what (players) did at the time.”42

No one can doubt Strong’s extraordinary athletic talent. Kendrick has compared him to longtime outfielder and Hall of Famer Dave Winfield. The 6-foot-6-inch Winfield played 22 seasons in the major leagues and hit 465 home runs. He batted .283, stole 223 bases, and drove home 1,833 runs, mostly for the San Diego Padres and New York Yankees. He made 12 All-Star teams and earned a plaque in the Hall of Fame in 2001, his first year on the ballot.

Winfield, a seven-time Gold Glove winner, has the distinction being drafted by four teams in three different sports. The Padres selected him with the fourth overall pick of the June 1973 amateur draft. The NBA’s Atlanta Hawks and ABA’s Utah Stars also drafted him, as did the NFL’s Miami Dolphins, although Winfield never played that sport at the University of Minnesota. “I tell people all the time that Ted Strong was Dave Winfield before we knew who Dave Winfield was,” Kendrick said.

“To me, Ted Strong epitomized that great athlete,” Kendrick wrote. “You’ll hear me refer to the players as some of the greatest athletes to play baseball – Ted Strong falls into that category. Six foot, six inches, freakish athlete. Powerful, great hitter, played every position except for pitcher and catcher.”43

Negro League stars like Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson earned far more attention than Strong on the baseball field. Globetrotters Goose Tatum and Marques Haynes did the same on the basketball court. Even so, Jenkins wrote, Strong “lived a life unlike any other.”44

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted seamheads.com and baseball-reference.com.

Notes

1 Seamheads.com https://www.seamheads.com/NegroLgs/player.php?playerID=stron01ted

2 Ryan Whirty, “Shining a Light on an Ex-Star,” South Bend (Indiana) Tribune, June 3, 2014: B1.

3 Denise Crosby, “Aurora Resident Authors Book about ‘Untold’ Baseball All-Star, Globetrotter,” Aurora (Illinois) Beacon-News, October 28, 2016, https://www.chicagotribune.com/suburbs/aurora-beacon-news/opinion/ct-abn-crosby-negro-league-baseball-st-1030-20161028-column.html

4 “Biography of Ted Strong Jr. Brings Light to Two-Sport Star,” Homeplatedontmove.wordpress.com https://homeplatedontmove.wordpress.com/2019/12/09/biography-of-ted-strong-jr-brings-light-to-two-sport-star/

5 Sherman L. Jenkins, Ted Strong Jr.: The Untold Story of the Original Globetrotter and Negro League All-Star (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2016), 12.

6 Jenkins, 15.

7 Bob Green, Spinning the Globe: The Rise, Fall, and Return to Greatness of the Harlem Globetrotters (New York: Harper, 2005), 17.

8 Green, 55.

9 Jenkins, 18.

10 Jenkins, 23.

11 Jenkins, 23.

12 Lloyd Lewis, quoted in Jenkins, 23.

13 Jenkins, 26.

14 Bill Young and Charles F. Faber, “J.L. Wilkinson,” SABR.org https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/j-l-wilkinson/

15 Young and Faber, “J.L. Wilkinson.”

16 Jenkins, 27.

17 “Globe Trotters Work Out with Sheboygan.” Chicago Defender, November 23, 1940: 22.

18 Jenkins, 49.

19 Jenkins, 32.

20 Green, 101.

21 Jenkins, 35.

22 Jenkins, 61.

23 Jenkins, 66.

24 Jenkins, 68.

25 Whirty, “Shining a Light on an Ex-Star.”

26 “Shining a Light on an Ex-Star.”

27 Jenkins, 70.

28 Jackie Robinson, I Never Had It Made (New York: HarperCollins, 1995), 24.

29 “Shining a Light on an Ex-Star.”

30 “Shining a Light on an Ex-Star.”

31 Austin Hough, “South Bend’s Connection to Negro Leagues Runs Deep,” Goshen (Indiana) News, June 4, 2020. Goshennews.com

32 Jenkins, 124

33 Green, 159.

34 Jenkins, 95.

35 Jenkins, 100.

36 Jenkins, 104.

37 Jenkins, 117.

38 “Shining a Light on an Ex-Star.”

39 David Condon, “In the Wake of the News,” Chicago Tribune, March 4, 1978: 70.

40 Denise Crosby, “Aurora Resident Authors Book about ‘Untold’ Baseball All-Star, Globetrotter.”

41 Jenkins, IX.

42 “Shining a Light on an Ex-Star.”

43 Hough, “South Bend’s Connection to Negro Leagues Runs Deep.”

44 Jenkins, 124.

Full Name

Theodore Relighn Strong

Born

January 2, 1917 at South Bend, IN (USA)

Died

March 3, 1978 at Chicago, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.