August 8, 1886: Louisville Slugger Pete Browning has his ‘batting clothes on’ and hits for a natural cycle

One of the rarest occurrences in baseball is the natural cycle. Of 334 known cycles in major-league history through the 2021 season, only 17 have been identified as natural cycles, meaning the single, double, triple, and home run happened in that order.1 In August 1886, three seasons after the first known natural cycle in big-league history,2 a prominent nineteenth-century slugger completed the second one, in an American Association game between the Louisville Colonels and the New York Metropolitans.

One of the rarest occurrences in baseball is the natural cycle. Of 334 known cycles in major-league history through the 2021 season, only 17 have been identified as natural cycles, meaning the single, double, triple, and home run happened in that order.1 In August 1886, three seasons after the first known natural cycle in big-league history,2 a prominent nineteenth-century slugger completed the second one, in an American Association game between the Louisville Colonels and the New York Metropolitans.

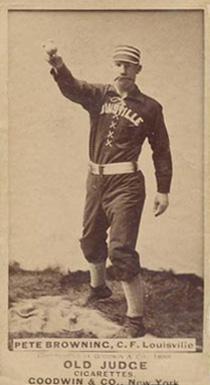

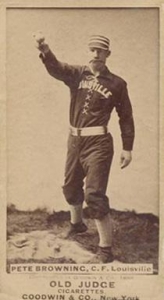

Pete Browning is believed to be the namesake for the Hillerich & Bradsby’s Louisville Slugger bat.3 The Louisville native began playing for the Colonels in 1882 and, as a 21-year-old rookie, led the league in batting average (.378), on-base percentage (.430), and slugging percentage (.510).4 By the beginning of the 1886 season, Browning still owned a .352 career batting average. He was indeed one of the game’s best hitters during the 1880s.5

On Sunday, August 8, 1886, at Louisville’s Eclipse Park, approximately 4,000 spectators6 came out to watch Browning, whose “terrific batting was the great feature of the game.”7 Browning “had his batting clothes on, getting a single in the first, a double in the third, a three-bagger in the sixth, and a home run in the ninth,”8 thus hitting for a natural cycle.

The Colonels, in second place in the American Association with a 49-39 record, hosted the cellar-dwelling Metropolitans (29-51) in the second game of a three-game series. The day before, the home team had won the opener, 5-1, behind solid pitching from left-hander Toad Ramsey9 and two hits by Browning.

Right-hander Jack Lynch started for the Mets. He had lost his previous seven starts, and there was talk that he was “suffering with a lame arm.”10 The Louisville Courier-Journal reported that his “delivery was utterly devoid of speed”11 and speculated that the veteran pitcher’s arm was worn out. Just two seasons earlier, in 1884, Lynch had won 37 games for New York, leading the team.

Guy Hecker, also a righty, did the pitching for the Colonels. In 1884 he had led the American Association with 52 wins and a 1.80 ERA. He was the Colonels’ team captain and had made their 1886 Opening Day start. Soon after, though, he was diagnosed with an inflamed nerve in his pitching arm, and the 30-year-old was replaced as captain.12 Although his pitching was reduced to about once a week, he was still leading his team as a hitter.13 After receiving “electronic-stimulation”14 therapy, he was back as the every-other-game starter and since July 1 he had won 12 of 14 starts coming into this game.

The game’s play-by-play descriptions are somewhat vague. The Courier-Journal reported, “The Louisvilles scored throughout the game by their hard hitting. The runs are too numerous to account for, but it is sufficient to say that they bunched their hits when men were on bases.”15 For example, Browning singled in the top of the first, and Louisville scored a run in that inning, but no further details are found in the papers.

New York tied the score in the bottom of the first without getting a hit. Candy Nelson was hit by a pitch, advanced to third on sacrifices by James “Chief” Roseman and Dave Orr, then scored on a wild pitch by Hecker.

Louisville took the lead back in the top of the second, plating three runs. Despite Browning’s double in the third, the Colonels did not score. Nor did a runner cross home plate in the fourth.

In the fifth inning, however, Louisville’s John Kerins “made a beautiful three-base drive,”16 and the Colonels added two runs to their lead. In the sixth, Louisville had four consecutive hits (including the triple by Browning), but could put only one run across home plate, due to poor baserunning. The home team added two more runs in the seventh, giving the Colonels a 9-1 advantage after seven innings.

In the eighth inning, Louisville manufactured another run when Chicken Wolf reached, “stole second and third in succession”17 and scored on a sacrifice. New York responded with two runs in its half of the eighth. Frank Hankinson reached on an error by Louisville first baseman Kerins. Steve Brady then lifted a fly ball to left field, and Browning dropped it for another error. Both runners moved up a base when Tom McLaughlin grounded out to first, and both scored when Charlie Reipschlager singled up the middle, cutting the lead to 9-3.

In the final frame, Louisville’s Amos Cross drove a ball to left “that appeared safe for three bases,”18 but Roseman made a spectacular one-handed catch for the out. Louisville still managed to score one run.

In the bottom of the ninth inning, Hecker hit the first two batters, Nelson and Roseman. Orr singled, driving in Nelson. Hankinson grounded a ball to shortstop Bill White, and Roseman scored on the out. Orr moved to third on the play. Jim Donahue popped the ball up in the infield, and Louisville catcher Cross “took off his mask and retired far back from the home plate,”19 making the catch. Orr tagged on the play, with no one covering home plate. That was all the Metropolitans could muster, and the game ended with Louisville winning, 11-6. New York had rallied to score five runs in the final two innings, but they were not enough.

Every Louisville player had at least one hit, and Lynch walked three. The Colonels scored runs in seven of the nine innings. This was their 50th victory of the season, which kept them 10½ games behind the first-place St. Louis Browns. Hecker struck out five New York batters. Only Nelson and Reipschlager had more than one hit off the Louisville right-hander, who scattered 10 hits through the nine innings, but he did hit three batters. Even Lynch had a hit for the Metropolitans, a clean single to short left field in the seventh. He batted just .160 for the season. Seven Metropolitans runners were left on base.

Hecker helped his own cause by getting four hits (all singles) in his five at-bats. He finished the season batting .341 and is the only pitcher ever to lead a major league in hitting.

At this point in the season, the Metropolitans were the worst team in the American Association and had defeated the Colonels in only four of 13 games.20 The Courier-Journal poked some fun at the New York team, telling its readers, “The Metropolitan players are all acrobats, and are open to circus engagements in the winter. They are excellent tumblers in the race for the championship.”21

Browning’s line score shows 4-for-5 with two runs scored. With his four hits, he had hit for the cycle. He joined the Philadelphia Athletics’ Lon Knight (July 30, 1883, against the Pittsburgh Alleghenys) as the only major leaguers to have completed a natural cycle to that date; of the 17 natural cycles as of the 2021 season, Knight and Browning were the only ones during the American Association’s tenure as a major league, which lasted from 1882 through 1891.

Browning’s achievement also marked the second time a major leaguer had hit for the cycle in 1886. In the National League, Fred Dunlap of the St. Louis Maroons did it on May 24 against the New York Gothams, and two weeks after Browning, the Detroit Wolverines’ Jack Rowe did so on August 21 against the Chicago White Stockings (also in the NL). Philadelphia Athletics’ Chippy McGarr added the fourth cycle of the season, when he accomplished the rare feat on September 23 against the St. Louis Browns, the second cycle of the season in the American Association.

Acknowledgments

This article was fact-checked by Jim Sweetman and copy-edited by Len Levin.

Sources

In addition to the sources mentioned in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com, MLB.com, Retrosheet.org, and SABR.org. Box scores and play-by-play are not available from either Retrosheet or Baseball-Reference.

Notes

1 After Knight and Browning (both of the American Association), they are Fred Carroll, Pittsburgh (NL), on May 2, 1887; Bill Collins, Boston (NL), on October 6, 1910; Bob Fothergill, Detroit (AL), on September 26, 1926; Tony Lazzeri, New York (AL), on June 3, 1932; Charlie Gehringer, Detroit (AL), on May 27, 1939; Leon Culberson, Boston (AL), on July 3, 1943; Jim Hickman, New York (NL), on August 7, 1963; Ken Boyer, St. Louis (NL), on June 16, 1964; Billy Williams, Chicago (NL), on July 17, 1966; Tim Foli, Montreal (NL), on April 21, 1976; Bob Watson, Boston (AL), on September 15, 1979; John Mabry, St. Louis (NL), on May 18, 1996; Jose Valentin, Chicago (AL), on May 27, 2000; Brad Wilkerson, Montreal (NL), on June 24, 2003; and Gary Matthews Jr., Texas (AL), on September 13, 2006.

2 Natural cycles are somewhat rare, occurring in only 5.50 percent of all cycles, where the order is known (17 of 309). For comparison (through the 2021 season), there have been 314 no-hitters, but only 21 perfect games (6.69 percent). Also, there have been 727 triple plays turned, but only 16 have been unassisted (2.2 percent).

3 Philip Von Borries, “Pete Browning,” SABR BioProject, found online at https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/pete-browning/. Accessed January 2022.

4 Browning also led the American Association in batting in 1885 (.362) and the Players’ League in 1890 (.373) while with the Cleveland Infants. In 1887 Browning batted .402 with the Colonels, but that was 33 points behind St. Louis Browns star Tip O’Neill.

5 In 2009, SABR’s Nineteenth Century Research Committee began selecting its Overlooked 19th Century Base Ball Legend—a nineteenth-century player, manager, executive, or other baseball personality not yet inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York. The first player selected was Browning.

6 “Half a Hundred: The Louisvilles Defeat the Mets and Score Their Fiftieth Victory,” Louisville Courier-Journal, August 9, 1886: 3. The Kansas City Times reported that “the game was witnessed by 5,000 people.” “Louisville 11—Metropolitans 6,” Kansas City (Missouri) Times, August 9, 1886: 2.

7 “Half a Hundred: The Louisvilles Defeat the Mets and Score Their Fiftieth Victory.”

8 “Lynch’s Lame Arm Makes Bad Work with the Mets’ Score,” New York Times, August 9, 1886: 2.

9 Ramsey led the Colonels in wins in 1886, with 38. His 66 complete games led the American Association, but so did his 207 walks allowed.

10 “Lynch’s Lame Arm Makes Bad Work with the Mets’ Score.”

11 “Half a Hundred: The Louisvilles Defeat the Mets and Score Their Fiftieth Victory.”

12 Bob Bailey, “Guy Hecker,” SABR BioProject. Found online at https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/guy-hecker/. Accessed January 2022.

13 Bailey. Hecker batted .417 in June, .379 in July, and .500 in August. He finished the 1886 campaign batting .341 in 84 games as a pitcher, first baseman, and outfielder, which was tops both for the Colonels and in the American Association. His teammate Browning finished the season second-best in the league at .340.

14 Bailey.

15 “Half a Hundred: The Louisvilles Defeat the Mets and Score Their Fiftieth Victory.”

16 “Half a Hundred: The Louisvilles Defeat the Mets and Score Their Fiftieth Victory.”

17 “Half a Hundred: The Louisvilles Defeat the Mets and Score Their Fiftieth Victory.”

18 “Lynch’s Lame Arm Makes Bad Work with the Mets’ Score.”

19 “Half a Hundred: The Louisvilles Defeat the Mets and Score Their Fiftieth Victory.”

20 At close of play on August 8, 1886, New York (29-52) was in last place in the American Association, a game behind the Baltimore Orioles (30-51-2). The Metropolitans finished the season in the seventh spot, three games above the Orioles.

21 “Notes and Comments,” Louisville Courier-Journal, August 9, 1886: 3.

Additional Stats

Louisville Colonels 11

New York Metropolitans 6

Eclipse Park

Louisville, KY

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.