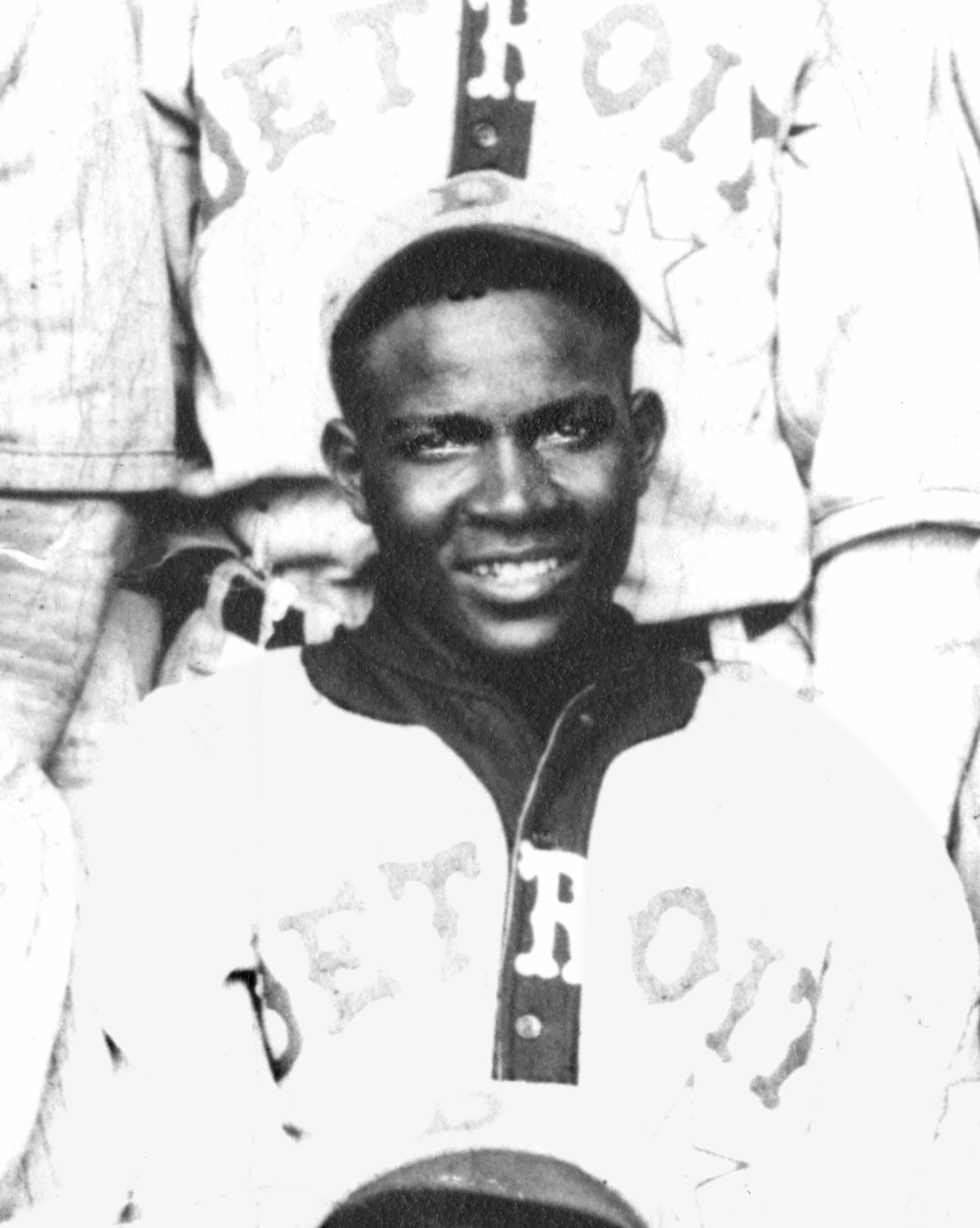

Andy Cooper

“In my estimation, the greatest black pitcher ever to pitch for Detroit — that’s for the Stars or the Tigers.” — Negro Leagues historian Dick Clark1

Left-hander Andy Cooper, one of the Negro League greats with a Hall of Fame plaque to his credit, ticked nearly all the boxes in his illustrious baseball career. Sad to say, in 1941, Cooper died in his mid-40s, curtailing his time as an accomplished manager and obscuring his exploits from future generations.

Per Mark Eberle’s research, Cooper was born on April 24, 1897, in Washington County, Texas, between Austin and Houston. He is one of nine Texas-born Negro Leaguers in the Hall.2

Cooper’s parents were Robert and Emma (née Gilbert).3 The 1910 US Census identifies him living with his mother and brothers east of Waco in Limestone County, but few details about Cooper’s childhood and youth are otherwise available.4 Earlier biographies report that he attended Paul Quinn College in Waco, but no records have been found to confirm this.5 That said, the military records of his uncle, Andrew Jackson Lewis, show employment at the college and a plausible link to Andy’s enrollment.6

Intermixed with his play in Texas, Cooper’s earliest playing days figure prominently in Kansas where he appeared with the Wichita Sluggers in 1917. Kansas teams often traveled to Texas and Cooper likely encountered such teams when living in the Lone Star State, making a leap to a Wichita squad conceivable. Eberle notes: “Newspapers usually referred to the team’s star pitcher as Lefty Cooper, but on July 19, the Wichita Beacon used the name ‘Cannon Ball Lefty’ Cooper. The same notice announced an upcoming game and provided a roster for the Sluggers, which included ‘Andrew Cooper’ as one of the pitchers. On July 22, a note in the Wichita Eagle mentioned that ‘Cooper was formerly with the Fort Worth Giants.’”7

Records show that Cooper migrated to another Wichita team later that year, the Southern Wonders. He returned home to Waco, where (with World War I in progress) he was drafted in June 1918 on his 21st birthday.8

Russ Cowans wrote in his June 21, 1941 obituary of Cooper that he “started his baseball career with the Waco Navigators in 1916, remaining there until 1918.”9 The Navigators connection is uncertain, but Bill Staples Jr., uncovered an April 12, 1919, Dallas Express article identifying pitcher Andrew Cooper on the Dallas Black Giants.10

Regarding his military service, Cooper reminisced in later years, “I was in France during the World War.”11 Earlier writings on Cooper’s baseball beginnings suggested that he was in the 25th Infantry Regiment. Contemporary research of digitized military records reveals that the “Lefty” Cooper who served in the 25th Infantry was actually Alfred Mayart “Army” Cooper, who pitched for the 25th in Nogales, Arizona, between 1922 and 1928.12

According to Staples, it’s plausible that Cooper served in one of the many labor units deployed to France out of Camp Travis, Texas, such as the 9th Company Depot Unit. According to The Stars and Stripes, the 9th Company boasted some of the strongest Black ballclubs in France.13

After his service, Cooper pitched with the Wichita Colored Giants in 1919. A newspaper account provides some sense of his emerging skill. “This young southpaw is about the class [of] Wichita’s hurlers. He has a world of stuff, speed, and a good baseball bean. His all-around work has made the Giants a team to be feared by the other clubs in the [City] league.”14

Word of Cooper’s emerging prowess on the mound got around among Black executives in the process of forming the first Negro National League. Tenny Blount of the Detroit Stars signed him for the 1920 season. Research by Staples indicates that Rube Foster recruited Dave Brown and James Brown of the Dallas Black Giants in April 1919, the same time that Cooper was with the team. Perhaps this created the opportunity for Foster to scout Cooper and recommend him to Blount.15 Cooper’s connection to Blount meant something to him; he reminisced later about “Tenny Blount, the man whom I broke into baseball with.”16

Managed by Pete Hill, the Stars finished a distant second to Chicago in the league’s 1920 inaugural year. Cooper helped fill out a rotation with right-handers Bill Gatewood and Bill Holland. Both would move on from the Stars within a couple of years; it was Cooper who would become the ace of the staff.

The Stars fell to fifth in 1921 with another Bill, Bill Force, joining the starting rotation. Cooper’s innings pitched increased significantly. Hill again served as player-manager; with Bruce Petway, Frank Warfield, and Edgar Wesley, he had a good nucleus. However, the team was outmatched by Chicago, the St. Louis Giants, Kansas City Monarchs, and Indianapolis ABCs.

In 1922, Cooper came into his own. The Detroit team, now managed by Petway and augmented by the solid hitting of Clint Thomas and Clarence Smith, finished in fourth place (42-31-1) in League play, 2½ games back of Chicago, KC, and Indianapolis in a very competitive league. The Chicago Defender’s Cowans later wrote, “While Cooper had plenty of native ability, much of his success could be attributed to the coaching of Bruce Petway, who succeeded Pete Hill as manager of the Stars in 1922.”17 Petway spent most of his playing career behind the plate and, as Cooper’s catcher and manager, had firsthand influence on Andy’s pitching. Buck O’Neil’s scouting reports on Negro League greats include one on Cooper, “Live arm, running fastball, ¾ arm action with a tight curveball, total command of all pitches.”18

According to Cowans, “Cooper had a keen knowledge of batters. He knew the weakness of every batter in the League and would pitch to that weakness when he was on the mound.”19 Petway managed the Stars for four years, retiring after the 1925 season. Cooper’s apprenticeship under Petway not only improved his pitching but also likely influenced his own managerial career.

From 1923 through 1927, Cooper was the anchor of the Detroit Stars’ pitching rotation. He was joined in the rotation over those five years variously by Force, Jack Combs, Steel Arm Davis, Buck Alexander, Fred Bell, Harry Kenyon, Lewis Hampton, Yellow Horse Morris, Ed Rile, and Bill Drake. The team finished third, third, fourth, fourth, and fifth, never really threatening the league leaders. In 1923, per NNL data verified (as of early 2022) by Seamheads’ Negro League Database, Cooper went 16-7, tossing nearly 200 innings with an ERA of 3.64. His 1925 season was even better: 12-2 with an ERA of 2.88. His performance got plenty of notice around the rest of the Negro League – in 1927, he became part of a famous trade when J.L. Wilkinson dealt multiple players to get Cooper’s left-handed talents.

At that time, the Kansas City Call reported, “In a trade announced on March 30, 1928, Hurley McNair, Grady Orange, and George Mitchell of the Monarchs were sent to Detroit for veteran pitcher Andy ‘Lefty’ Cooper.” According to the Call, “Owner Wilkinson decided that he could use a player of the type to a good advantage, as he would be in the lineup from the beginning of the season.”20

The Monarchs were the class of the Negro National League, having won multiple league championships and the first Negro League World Series in 1924 against Hilldale. The 1928 squad was very good, with a formidable .633 winning percentage, but came in second to a St. Louis Stars team managed by Candy Jim Taylor with three future Hall of Famers—Willie Wells, Cool Papa Bell, and Mule Suttles. Cooper went 12-7 with an ERA of 3.38. He was part of a stellar starting staff of Bullet Joe Rogan, Chet Brewer, William Bell, and Army Cooper.

In 1929, the Monarchs let it loose, winning at a .788 clip with a league record of 63-17. Second-place St. Louis was 12 games distant. Cooper, Brewer, and Bell all tossed in the vicinity of 150 innings in league play. Brewer and Cooper shared the team lead for wins at 15 – yet as good as Cooper was that year, it was a career year for Brewer, who had a 1.93 ERA compared to Cooper’s 3.52 and 14 complete games to Cooper’s eight. Managed by Rogan, the Monarchs won both the first- and second-half league championships.

The Monarchs’ starting rotation was already strong and was then bolstered by two newcomers, Henry McHenry and Johnny Markham, aged 20 and 21, respectively. Perhaps that was why Kansas City did not sign Cooper for the 1930 season. He instead reconnected with his former team, Detroit. The Stars were playing in a new ballpark, Hamtramck Stadium, following the ruin of Mack Park in a fire the year before. Initially, longtime Stars great Turkey Stearnes opted to go East that year for a bigger contract with the Lincoln Giants. His departure might have been also precipitated, some thought, because Hamtramck was not friendly to left-handed batters. Stearnes eventually returned to Detroit that summer; he and Cooper led their team to the second-half championship of the Negro National League and a postseason best-of-seven series with first-half winners St. Louis. Unfortunately, Detroit lost the series in seven games, hampered in part because Cooper got hurt before the series and could pitch just sparingly, appearing in relief in games two and seven.21

The Stars, sold by owner John Roesink to Everitt Watson after the 1930 season, collapsed in mid-1931 along with rest of the Negro National League. Cooper spent most of the 1931 regular season out of the country, touring with the Philadelphia Royal Giants in Hawaii. Earlier research suggests that he was back with the Monarchs for a few games later that year; however, this more likely was Army Cooper. At the end of the season, Kansas City played the Homestead Grays in a nine-game championship series as the best teams from the East and Midwest. Again, earlier records suggest that Andy Cooper finished 1-1 in the series, but the Pittsburgh Courier in several editions refers to the aforementioned Army Cooper as the KC pitcher who appeared.22

Regarding his personal life, Cooper apparently was married three times. His 1918 draft card identified a first marriage. His second wife, Norine, died in 1931, two years after the birth of their only child, Andy Jr. After shee passed away, Cooper married again.23

By then in his mid-30s, Cooper’s premier pitching days were behind him. He remained an occasional starter for KC but was used more as a reliever. According to Monte Irvin, “Cooper was a rarity for his time, in the Negro Leagues and the major leagues, a relief specialist. Like so many pitchers in his day, Cooper was used as both a starter and a reliever. But his specialty was relief. He holds the all-time Negro Leagues records for saves and was the closest thing in his day to what is known as a closer.”24

Cooper’s second stint with the Monarchs lasted from 1932 until 1939 as a pitcher; he served as manager from 1936 to 1940. Wilkinson offered Andy the managerial reins in 1935 after Joe Rogan’s long tenure at the helm.25 Cooper demurred, though, and Sam Crawford stepped in that year instead. It was also in 1935 that the Brooklyn Eagles under manager Ben Taylor offered hefty contracts to Cooper and fellow Monarchs Newt Allen, Chet Brewer, George Giles, and T. Baby Young. Only Giles made the jump, beginning the season at first base for the Eagles and becoming player-manager in late May.26

Cooper accepted Wilkinson’s managerial offer in 1936. In his inaugural year as skipper, he led the Monarchs to the best record among independent teams. In 1937, Kansas City joined the Negro American League and from 1937 to 1940, Cooper led them to four successive first-place finishes.27

Buck O’Neil described Cooper’s managerial style as follows:

He was the best manager I ever played for, and I played for some good ones. He was also a father figure and a teacher, and he helped me a great deal, as he did other players who were still developing. He could be stern if he had to be, but he was easy to be around…With Andy, you felt like you were violating a trust if you broke the rules, so he got better results than the manager who tried to be tough.28

Fellow Monarch and Hall of Famer Hilton Smith, who pitched alongside Cooper and played for him as a manager, remarked, “Andy Cooper was a smart manager, and he was a great teacher—great teacher. A student of baseball. He would take me aside and just sit there and talk to me, and I’d watch how he’d pitch.”29

Willie Simms, another of Cooper’s teammates in Kansas City, reflected, “Andy Cooper was my manager; he was one of the smartest guys about the game of baseball that you ever looked at, and in his day, he was a left-handed pitcher, and a good one, too. He knew how to get the pitch on hitters inside and out. Away. And he knew how to get it in on their hands and make ’em break up their bats and he’d laugh at ’em.”30

Cooper’s four successive first-place league finishes with Kansas City took place when there was no Negro League World Series. Joining the Negro American League in 1937, the Monarchs dominated the circuit, whose teams included the Chicago American Giants, Memphis Red Sox, and Birmingham Black Barons.

Cooper’s most famous pitching performance came late in his career, against rival Chicago. Chicago disputed the Monarchs’ 1937 Negro American League crown and the two teams agreed to a five-game playoff with games in five different midwestern cities to settle the score. Kansas City won the series three games to one, but it was Game Two – a 17-inning 2-2 tie – that was historic. Willie Foster started for the American Giants and Cooper for the Monarchs. With Chicago as the home team on a chilly day, Cooper gave up two runs in the bottom of the first on successive RBI doubles by Alec Radcliff and Turkey Stearnes. These were the only runs Cooper surrendered. He walked four batters and struck out seven.

The Monarchs tied the game in the top of the seventh, scoring on an RBI single and a wild pitch. Foster was hurt on a line drive in the inning and replaced by Sug Cornelius. The game continued for ten more scoreless frames before being called.31 The Pittsburgh Courier wrote in its report of the contest, “The veteran Andy Cooper, going the entire route for the Monarchs, pitched probably one of the greatest games of his career. He rose to the heights when the Giants filled the bases in the thirteenth with none out by whiffing Stearnes and causing the dangerous [Subby] Byas to rap into a double play, Cooper to Else [the catcher] to Strong.”32

As remarkable as Cooper’s pitching and managing career was with the Stars and Monarchs, his exploits on several other playing fields underscore the nature of Black baseball in the Negro League era, one often lost in the storytelling. Cooper played in the Caribbean and California in their respective winter leagues. He barnstormed with the Stars and Monarchs33, and on all-star teams between league games and in the offseason. Andy Cooper was one of a handful of Black ballplayers who made traveled to the Far East to showcase the Black game.

Cooper’s Caribbean play encompassed three seasons in Cuba: 1923-1924, 1924-1925, and 1928-1929. He pitched for Habana in his first visit and then for Almendares. Cooper played on first-place Almendares in the winter of 1924, appearing in nine games, pitching four complete games with a record of 3-2.34 The team was loaded with the likes of Biz Mackey, Newt Allen, Dick Lundy, John Henry Lloyd, Clint Thomas, Oscar Charleston, Bullet Joe Rogan, and Adolfo Luque. According to Jorge Figueredo, “Almendares reclaimed the title by such an ample margin that the league, as was customary in those days, stopped the activities to prevent financial harm to the different clubs.”35 In 1925, Cooper played on the All-Yankees (i.e., American ball players) versus the All Cubans in an eight-game series. He got the victory in one of the five games won by the All-Yankees.36

Cooper appeared in the California Winter League for five seasons: with the St. Louis Stars in 1923-1924; the Philadelphia Royal Giants in 1926-1927, 1927-1928, and 1930-1931; and the Cleveland Stars in 1929-1930. William McNeil’s compilation of Cooper’s appearances shows him as having pitched in 43 games, winning 22 with a .786 winning percentage and four shutouts.37

Cooper was also a part of the East-West Colored All-Star Game, despite having played most of his career prior to the game’s debut in 1933. Cooper played in one game, pitching a scoreless sixth inning for the West in a 10-2 contest won by the East in 1936. He coached in both 1939 games and went 1-1 as a manager for the West in the 1938 and 1940 games.38

Barnstorming was an essential element for Black ballplayers and Cooper was a part of three famous competitions: the 1934 Denver Post Tournament, games for and against the iconic Bismarck Churchills of the mid-1930s, and contests against major-leaguers, including the likes of Dizzy Dean’s all stars.

In 1934, the Monarchs were invited to play in the prestigious Denver Post Tournament, the first Black team ever to appear. KC finished 5-2, losing both of its games to the House of David, led by Grover Cleveland Alexander. Although Cooper pitched in the tournament, Willie Foster and Chet Brewer did the bulk of the pitching for Kansas City, with the latter starting and losing both games the Monarchs played against the House of David. In those two games, Brewer lost first to Satchel Paige (acquired from the Crawfords to pitch in the tournament), 2-1. He then dropped a 2-0 decision to Spike Hunter in the finale, when the House of David was crowned champions.

Cooper was not part of Neil Churchill’s 1935 squad that won the first National Semi-Pro Baseball Tournament in Wichita. However, he did play on the Monarchs in their barnstorming games against Bismarck in 1934 and 1935, He was also borrowed by Churchill to pitch an occasional game for Bismarck itself.

Most exotically, Andy Cooper, playing for the Philadelphia Royal Giants, was part of three goodwill tours to the Far East—1927, 1932-1933, and 1933-1934—in which the team had a combined record of 97-3-2.39 He also played for Philadelphia on its barnstorming trip to Hawaii from late May to early August 1931.

The Philadelphia team was promoted and managed by Lon Goodwin, a West Coast entrepreneur with strong ties to the California Winter League. Its first appearance in Japan, Korea, and Hawaii followed a season in the California Winter League. Cooper competed alongside Frank Duncan, Rap Dixon, and Biz Mackey.

During the tour, a local Japanese magazine wrote “with regards to pitching, Cooper threw on the first day, which seemed to indicate that he was the ace of the team. His performance confirmed that he did indeed have the skill of an ace.”40 In Japan, Cooper started and won all eight games in which he appeared, with an ERA of 1.63.41 The Chicago Defender’s headline on June 25, 1927, said it all, “Royal Giants Won 26, Tied One on Their Japanese Tour.”42

The tour’s timing created a problem for the Negro National and Eastern Colored Leagues; both issued $200 fines and 30-day suspensions to the four players from the Royal Giants who were on the payrolls of league teams and missed their early-season games (Cooper for Detroit, Duncan for the Monarchs, Dixon for Harrisburg, and Mackey for Hilldale).43 Except for Duncan, the fines and suspensions were not enforced.44 Cooper made his debut with the Detroit Stars on July 24.45

The Royal Giants and Cooper made their second visit to Japan in the winter of 1932-1933. Cooper and Mackey again led Philadelphia, stopping over in Hawaii and winning all nine games they played (Cooper won three, giving up only two runs).46 Their combined tour to Hawaii, Japan, Korea, and the Philippines amounted to 49 wins, two losses, and one tie.47

The Royal Giants’ tours, compared to the excursions by American and National League All-Star squads, were more welcomed by their Japanese hosts. “This traveling team made up of black players…was kinder and more gentleman-like than the white major leaguers.”48

Philadelphia with Cooper made one more tour, this time from November 1933 to April 1934, playing 35 games in Japan, China, the Philippines, and Hawaii. Cooper was joined by a 44-year-old Bullet Joe Rogan, Newt Allen, and Chet Brewer.

Historian Kazuo Sayama “credits the 1927 tour…as the inspiration for the start of professional baseball in Japan in 1936.”49 Cooper recollected, “After some negotiation with us he [Lon Goodwin] mailed out contracts. My contract was for 6 months at $140 a month and all expenses from the time I bailed from the U.S.A., until I returned. All the contracts were relatively the same. At the time I was under contract of the Detroit Stars, but this offer looked good to me, so I jumped and signed to go to Japan. Arrangements for passports were made and sailing date announced; on April 10, this vanguard of ball players left for Los Angeles, in cars, for San Pedro, our sailing port.”

Cooper added, “We embarked on April 10th and landed at Yokohama May 2nd. Some of the boys were frightened, it was their first voyage; I had been to sea before, having gone to France during the war and later to Cuba to play ball…The Japanese show no personal prejudice or irrelevancies toward the Negro. We stopped at some of the best hostelries in Japan. We were welcome to go into any public place in Japan without any molestation of any kind.”50

Of Cooper, Bill Staples Jr. remarked, “Between 1927 and 1934, he was among the most active Trans-Pacific barnstormers in Negro League history, spending 517 days traveling across the ocean and playing abroad.”51 Only Lon Goodwin himself logged as much time.

Cooper’s early connection to Wichita stood him in good stead later in his career when he made the city his home. In 1934-35, Cooper was invited by The Negro Star to author a column called “Stove League.” One of his first columns included Cooper’s perspective on “What does it take to make a great pitcher?”

Besides ambition and hard work, it takes headwork, strategy, and psychology. A pitcher should be able to tell as nearly as possible what the batter is thinking about doing. He [studies] the idiosyncrasies of individual batsmen. With these attainments may go a keen mentality, a quick thinking, scheming baseball brain and, yet nature must richly endow a boy with talents that make a great pitcher… The main issue [is that] a pitcher must practice control.52

Cooper’s managerial career was cut short by a heart ailment that precluded his joining the Monarchs for their 1941 spring training. The June 14, 1941, Chicago Defender noted “With his health in decline, Cooper’s mother Emma brought him to her home in Waco, where he passed away on June 3 at the age of 45. Cooper was buried in Greenwood Cemetery in Waco.”53 In the following week’s edition, Cowans noted, “[Cooper] never possessed the fine assortment of curves held in the supple arms of other pitchers. However, he did have what so many pitchers lack—sterling control.”54

Sixty-five years later Andy Cooper’s special talents were recognized by a special committee established by the Hall of Fame to assess and recommend the candidacy of Negro League greats for induction. The Committee eventually chose 17 for entry, Cooper among them. His Hall of Fame plaque read, in part, “Ranks among Negro League leaders in virtually every career pitching category and won more than two-thirds of his decisions.”55

Cooper’s son, Andy Jr., then 77, attended the induction. “You’ve got to remember anything that pertained to Black people back then [has only been] uncovered in recent years,” he reflected.56 He has been proven right; further research has substantiated Cooper’s place in the Hall of Fame.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Bill Staples Jr., and Mark Eberle for their insights on Cooper’s time in Texas and Kansas. Thanks to Larry Lester for his review and additions to this biography.

This biography was reviewed by Phil Williams and Rory Costello and fact-checked by David Kritzler.

Sources

All statistics cited are from Seamheads.com, unless otherwise noted in the text or in the notes below.

Notes

1 Andy Cooper, Baseball Hall of Fame, https://baseballhall.org/hall-of-famers/cooper-andy.

2 Alongside Andy in the Hall are fellow Texan Negro Leaguers Ernie Banks, Rube Foster, Bill Foster, Biz Mackey, Louis Santop, Hilton Smith, Willie Wells, and Smokey Joe Williams.

3 Mark E. Eberle, Baseball Career of Andy Cooper in Kansas (Hays, Kansas: Fort Hays State University, 2021), 2. According to Eberle, Cooper “was born to Robert and Emma (Gilbert) Cooper in Texas. It is often reported that he was born in Waco, but his 1918 draft registration card listed his birthplace as Washington County (east of Austin). His birthdate is also uncertain, reported to be April 24 in 1896 (tombstone), 1897 (draft card), or 1898 (death certificate). The fact that he registered for the draft on 5 June 1918 suggests that he turned 21 that year, which would make his birthdate 24 April 1897. This is corroborated by the notice of his intent to marry [Norine Adams] filed in California and published in January 1928. It listed his age as 30 about 16 weeks before his birthday in April.”

4 Eberle, 2.

5 Robert F. Darden, “In Search of Andy Cooper: The hunt for Waco’s forgotten baseball Hall of Famer,” Waco Magazine, www.wacoan.com/in-search-of-Andy-Cooper/.

6 Bill Staples Jr., Andy Cooper’s Life in Texas, Prior to 1920 (Unpublished research) accessed on January 2, 2022.

7 Eberle, 2.

8 Eberle, 2.

9 Russ J. Cowans, “Death of Andy Cooper Recalls Detroit Playing,” Chicago Defender, June 21, 1941, 22.

10 J. Alba Austin, “Base Ball,” Dallas Express, April 12, 1919, 11.

11 Andy Cooper, “Stove League,” The Wichita] Negro Star, November 30, 1934.

12 Staples Jr. unpublished research; Alfred Cooper in the U.S., Veterans Administration Master Index, 1917-1940, Ancestry.com.

13 The Stars and Stripes (Paris, France), April 25, 1919, 7, tinyurl.com/2p9a245d. In his unpublished research, “Jodie William Adams in the U.S., Headstone Applications for Military Veterans, 1925-1970,” Staples Jr. writes that Jodie Adams, the father of Cooper’s second wife, Norine, served in the 9th Company, 3rd Battalion, 165th Depot Brigade during the War, a possible connection to Cooper’s military career that merits further investigation.

14 Wichita Eagle, August 3, 1919, 2.

15 Bill Staples Jr., “Black Giant: Biz Mackey’s Texas Negro League Career” in Black Ball: A Journal of the Negro Leagues (McFarland, Spring 2008), 99-100.

16 Stove League by Andy Cooper in Amusements and Sports by Bennie Williams, The Wichita Negro Star, December 21, 1934, 3.

17 Russ J. Cowans, “Death of Andy Cooper Recalls Detroit Playing,” Chicago Defender, June 21, 1941, 22.

18 Buck O’Neil Scouting Reports, Andy Cooper Player File Baseball Hall of Fame.

19 Chicago Defender, June 21, 1941, 22.

20 William A. Young, J.L. Wilkinson and the Kansas City Monarchs: Trailblazers in Black Baseball (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2016), 63.

21 John Holway, The Complete Book of Baseball’s Negro Leagues: The Other Half of Baseball History (Fern Park, Florida: Hastings House, 2001), 261.

22 Holway, 281. Holway names both Coopers as appearing in the Series. However, the September 5, 1931, Pittsburgh Courier refers to Army Cooper as the KC hurler. William G. Nunn, “Divide Close Pair in Cleveland Arena; Kays Win 2, Lose 3,” Pittsburgh Courier, September 5, 1931, 14. And in Fay Young’s preview of the series and players on both teams, Army Cooper is highlighted among the Monarchs pitchers, but no Andy. Frank A. “Fay” Young, “A Digest of the Sports World,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 29, 1931, 15.

23 Eberle, 8.

24 Monte Irvin, Few and Chosen: Defining Negro Leagues Greatness (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2007), 145.

25 “KC Monarchs Offer Andy Cooper Managerial Berth,” The [Wichita] Negro Star, February 8, 1935, 5.

26 “Brooklyn is angling for Monarchs Stars,” The [Wichita] Negro Star, January 4, 1935, 3; “Hot off the Wire,” The [Wichita] Negro Star, February 1, 1935, 3.

27 Leslie A. Heaphy, editor, Satchel and Company, Essays on the Kansas City Monarchs, Their Greatest Star, and the Negro Leagues (1869-1960) (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2007), 105.

28 Buck O’Neil, with David Wulf and David Conrads, I Was Right on Time (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1996), 90-91.

29 John Holway, Voices from the Great Black Baseball Leagues, Revised Edition (New York: Da Capo, 1992), 287.

30 Brent Kelley, The Negro Leagues Revised: Conversations with 66 More Baseball Heroes (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2000), 48.

31 John Holway, The Complete Book of Baseball’s Negro Leagues: The Other Half of Baseball History (Fern Park, Florida: Hastings House, 2001), 341-342.

32 “Chicago, Kay Cee Monarchs Battle 17 Innings, Tie 2-2,” Pittsburgh Courier, September 18, 1937, 16.

33 Both Baseball Reference and Seamheads also identify Cooper as pitching one game for the Chicago American Giants in 1937.

34 Jorge S. Figueredo, Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 1878-1961 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2003), 153-179.

35 Figueredo, 157.

36 Figueredo, 162.

37 William F. McNeil, The California Winter League: America’s First Integrated Professional Baseball League (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2002), 89-245.

38 Larry Lester, Black Baseball’s National Showcase: The East-West All-Star Game, 1933-1962, Expanded Version (Kansas City, Missouri: Noirtech Research, Inc., 2020), 82-140.

39 Kazuo Sayama & Bill Staples Jr., Gentle Black Giants: A History of Negro Leaguers in Japan (Fresno, California: Nisei Baseball Research Project Press, 2019), 178.

40 Sayama and Staples Jr., 39-40.

41 Sayama and Staples Jr., 249.

42 Chicago Defender June 25, 1927.

43 “30 Suspension for Four Players,” [Baltimore Afro-American, July 9, 1927, 15.

44 Fay Says—Mackey Jumped,” Chicago Defender, September 24, 1927, 8.

45 “One Big Inning Wins for Stars,” Detroit Free Press, July 24, 1927, 18.

46 Sayama and Staples Jr., 316.

47 “Royal Giants Nine Return to U.S. with Only Two Defeats in 52 Games,” [Baltimore Afro American, February 4, 1933.

48 Sayama and Staples Jr., 123.

49 Sayama and Staples Jr., 266.

50 “Stove League by Andy Cooper,” The Wichita Negro Star, 30 March 1934, 3.

51 Sayama and Staples Jr., 352.

52 “Stove League by Andy Cooper,” The [Wichita] Negro Star, November 16, 1934, 5.

53 “Andy Cooper Dies,” Chicago Defender, June 14, 1941, 23.

54 Cowans, 22.

55 Andy Cooper Baseball Hall of Fame Plaque.

56 Shawn Windsor, “The long journey to the Hall of Fame for Lefty Cooper began with newspaper box scores and a man from Ypsilanti,” Detroit Free Press, July 23, 2006.

Full Name

Andrew Lewis Cooper

Born

April 24, 1897 at Washington County, TX (US)

Died

June 3, 1941 at Waco, TX (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.