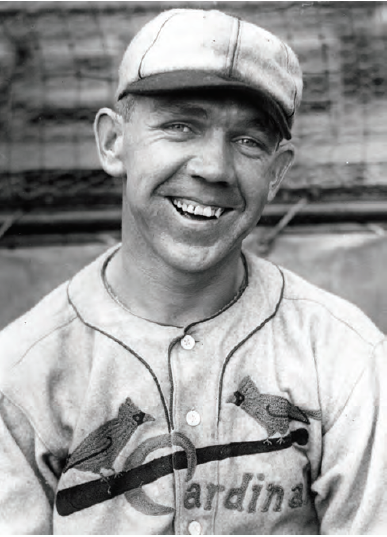

Bill Hallahan

Considered one of the hardest throwers of his era, two-time National League strikeout king Wild Bill Hallahan lived up to his name by leading the league in walks and wild pitches three times each in the early 1930s. The left-hander, who had a reputation as a big-game pitcher during his best years with the St. Louis Cardinals (1930-1935), tossed two shutouts in the World Series and won 102 games in his 12-year big-league career, most of it with the Cardinals. “When Hallahan is in control,” said Charlie Grimm of the Cubs, “he is a mighty hard man to beat. He puts more stuff on the ball than (Lefty) Grove.”1 Hallahan was also the NL’s starting (and losing) pitcher in the inaugural All-Star game in 1933.

Considered one of the hardest throwers of his era, two-time National League strikeout king Wild Bill Hallahan lived up to his name by leading the league in walks and wild pitches three times each in the early 1930s. The left-hander, who had a reputation as a big-game pitcher during his best years with the St. Louis Cardinals (1930-1935), tossed two shutouts in the World Series and won 102 games in his 12-year big-league career, most of it with the Cardinals. “When Hallahan is in control,” said Charlie Grimm of the Cubs, “he is a mighty hard man to beat. He puts more stuff on the ball than (Lefty) Grove.”1 Hallahan was also the NL’s starting (and losing) pitcher in the inaugural All-Star game in 1933.

William Anthony Hallahan was born on August 4, 1902, in Binghamton, New York, the fourth of seven children born to John and Alice (Kane) Hallahan. Binghamton, at the confluence of the Susquehanna and Chenango Rivers in New York near the Pennsylvania border, was a developing manufacturing center and transportation hub affording families like the Hallahans a middle-class lifestyle. John Hallahan, whose parents were from Ireland, was born in New York and worked as an inspector for the Delaware & Lackawanna Railroad. Alice came from Pennsylvania. By the time Bill was 18 months old, his parents were concerned that he was left-handed. His mother tried everything to break that habit, from tying his arm behind his back to putting his arm in a sling, but nothing helped. In his adulthood Hallahan said he had few pleasant memories of childhood other than playing baseball. At school he was chided for his big ears and small stature. “I muffed most of my studies,” he admitted, and failed several grades.2 Young Bill dreamed of baseball, started pitching for his grammar school by the age of 11, and looked forward to the day he could quit school, which he did after the eighth grade.

After years of playing sandlot ball, Hallahan approached Bill Fischer, manager of the prosperous and successful semipro team for the Endicott-Johnson shoe factory in the highly competitive industrial leagues in Binghamton, for a tryout. Though Fischer turned the 19-year-old Hallahan away because of his youth and small size (just 130 pounds), he suggested that he contact John Haddock, a former minor-league catcher and the manager of the Corona Typewriter semipro team in Groton, New York, about 50 miles northwest of Binghamton.3 Hallahan reported to Haddock, got a job in the factory, and secured a spot as a pitcher on the team, earning about $35 per week. A “sensation in semipro circles,”4 Hallahan was a strikeout artist and was known as the hardest thrower around. Other semipro teams actively recruited him, but he stayed loyal to Corona and continued to pitch for them until after the 1923 season. Legend has that he struck out 55 batters in his last three games while surrendering just six hits. Drawing the attention of professional scouts, Hallahan signed a contract with the Syracuse Stars of the International League after the 1923 season.

Branch Rickey, general manager and manager of the Cardinals, had acquired a half-interest in the Stars in 1921, and was in the process of building the first modern farm system. In 1924, the 21-year-old Hallahan reported to Bradenton, Florida, where the Cardinals and Stars conducted spring training together. “He’s so wild, he can hardly hit the backstop, but there’s a pitcher who someday will pitch and win a World Series game,” Rickey supposedly said of Hallahan during his first spring training. 5 The legend of “Wild Bill” was under way. Hallahan began the season with manager Shag Shaughnessy’s Stars but after he had made eight appearances, the Cardinals purchased his contract in mid-June and put him on the fast track to the majors. Hallahan was optioned to Fort Smith in the Class C Western Association, where he made five starts and pitched 43 innings, then was promoted to Kalamazoo in the Class B Michigan-Ontario League. In two months with Kalamazoo, Hallahan won eight games, surrendered a league-low 6.7 hits per nine innings, and tied for the third-best ERA (2.80); but true to Rickey’s assessment of his wildness, he issued 79 walks in 106 innings (6.7 per nine innings). In September, Hallahan was called up by the Cardinals. “[I] was permitted to sit in the dugout, in uniform, and watch the big-league ballgames,” he said.6

Hallahan’s speed was as tantalizing as his lack of control was frustrating. During spring training in Stockton, California, in 1925, he was praised for his “speed and curves.”7 Rickey predicted that “that boy will make good if he can keep control of his stuff.”8 Hallahan made the team and debuted on April 16 at Redland Field in Cincinnati when he took over for Bill Sherdel to start the fourth inning. He pitched scoreless two-hit ball the rest of the way, striking out two and walking three in a 7-3 loss. On May 7 Hallahan earned his first big-league win by pitching two hitless innings of relief against the Pirates at Forbes Field. “I thought I was going to make the grade,” he said, but after two ineffective outings (five earned runs in 5⅓ innings), he was optioned to Syracuse to work on his control.9 “I was disappointed,” said Hallahan, who struggled with the Stars, winning eight, losing 15, and walking 114 in 178 innings.

“Hallahan — Big Show,” read a headline about the hard thrower’s third spring training with the Cardinals.10 Playing for Rogers Hornsby, who had replaced Rickey as manager in 1925, Hallahan joined a strong staff with veteran starters Sherdel and Jesse Haines as well as Flint Rhem and Hallahan’s boyhood hero, Grover Cleveland Alexander, who have come on waivers from the Cubs in June. Described as a “quiet mannered” and “soft spoken” man,11 Hallahan roomed with 19-year-old pitcher Ed Clough (they were dubbed the “silent twins”12), and Hallahan bristled under the authoritarian rule of Hornsby, who liked his players to be as vocal and fiery as he was.

During the Cardinals’ exciting march to the first pennant in their history, Hallahan was used sparingly. In 16 relief appearances, he pitched well (3.03 ERA with 14 walks in 38⅔ innings), but struggled in three starts (5.00 ERA with 18 walks in 18 innings). With only two appearances after August 9, Hallahan was no doubt surprised and a bit rusty when he relieved Hi Bell in Game Four of the World Series against the New York Yankees in Sportsman’s Park. In his only appearance in the Cardinals’ dramatic and unexpected Series victory, Hallahan pitched two innings, surrendering one run and two hits, and walked three. It was his last major-league game for more than two years.

Optioned to Syracuse to start the 1927 season, Hallahan was subject to recall on one day’s notice but remained with the Stars the entire season. “Hallahan, when he is locating the plate,” said Syracuse manager Burt Shotton, “can win in any league.”13 He posted a team-high 19 wins but had a tendency to tire early in games because he threw so hard. He led the International League with 195 strikeouts (a team record) and 135 walks in 229 innings.

Wild Bill enjoyed a breakthrough year with the Houston Buffaloes of the Class A Texas League in 1928. Described as “one of the greatest sensations the league has ever seen,” he won 23 games, and led the league with 244 strikeouts, 149 walks, a sparkling 2.25 ERA, and 276 innings pitched.14 Associated Press reports in August claiming that Hallahan would soon join the Cardinals in their pennant race with New York Giants and Chicago Cubs proved to be wrong. Wild Bill remained with the Buffaloes and led them to their first league title in 16 years by winning three games in the championship series. He capped the season by winning one game in the Buffaloes’ Dixie Series championship over the Birmingham Barons. The Gunslinger of the West, Wild Bill had finally lived up to his name. “Hallahan is such a great natural pitcher that he doesn’t have to bother to pitch to the batter’s weakness,” said Cardinal scout Charley Barrett, who charted Hallahan’s progress all season. “All he has to do is get the ball over the plate.”15

Arriving at Avon Park, Florida, for his sixth consecutive spring straining with the Cardinals after offseason surgery on his big toe (the result of pushing off the pitching rubber), Hallahan competed for a spot on the NL’s oldest staff (averaging 32.2 years). “There will probably be a lot of shuffling around the batter’s box when Bill Hallahan takes the mound,” read one report about the excitement around Wild Bill.16 Named to the Opening Day roster, Hallahan was quick to credit catcher-manager Frank Snyder at Houston for his transformation, “I had been living up to the name of ‘Wild Bill’ for a long time until Snyder got hold of me,” he said. “He was the first one who ever had confidence on me.”17

That confidence did not transfer to manager Billy Southworth who used Hallahan just eight times before he was replaced as skipper in late July. While the reigning pennant winners struggled to play. 500 ball, Hallahan labored to throw strikes. Through August, Wild Bill issued 35 free passes in 30 innings (including a career-high ten in his first complete game, an 8-2 loss to Brooklyn on July 31). New manager Bill McKechnie, renowned for his handling of pitchers, gave Hallahan a chance to prove himself in September. Hallahan responded by winning four of seven starts, tossing four complete games, and posting a stellar 3.20 ERA over 59 innings. Even more promising was his improved command.

The Cardinals’ sixth different Opening Day manager in the last six seasons, Gabby “Old Sarge” Street, a former big-league catcher, took Hallahan under his wing in 1930. He thought Wild Bill’s problems resulted from a lack of concentration, so he decided to scrap Branch Rickey’s complicated (some said convoluted) signal-calling system which involved the pitcher adding and subtracting from the catcher’s signs, so that the pitcher could think exclusively about pitching.18 Hallahan had a tendency to stare at the ground and then look up in his delivery, thereby losing his sense of direction. “Keep your eyes on the plate and the batter,” Street told him. “Don’t turn you head away or look down when you deliver the ball.”19

Hallahan responded in his first start of the season by tossing a complete game, striking out 11 in an 11-1 shellacking of the Cubs. His season-high nine walks were tempered by just two hits (both singles). Street was patient with Hallahan whose record (8-7) and ERA (5.47) were as unimpressive as the Cardinals’ 48-49 record at the end of July. On August 10 Hallahan tossed his first big-league shutout, a two-hitter, striking out 12 while issuing just two walks to reduce the NL-leading Brooklyn Robins’ lead over fourth-place St. Louis to nine games. “St. Louis players insist that Hallahan is as fast as (Dazzy) Vance and faster than Robert Moses Grove,” said the Associated Press.20 With every game seemingly a must-win contest, the Cardinals reeled off 23 wins in 32 games in August and started September by winning 11 of 13 games to find themselves just a half-game behind Brooklyn on the eve of a possible pennant-deciding three-game series at Ebbets Field.

The most important game of the Cardinals’ 1930 season comes across like a soap opera. Flint Rhem, a 20-game winner in 1926 but whose career and behavior since then had been affected by alcoholism, was scheduled to take the mound against Vance, the seven-time NL strikeout king, in the opening game. When Street discovered that Rhem had been out drinking all night and was nowhere to be found, he turned to Rhem’s roommate, none other than Hallahan, and named him starter. Hallahan had injured his hand hours before when he smashed a cab door on his fingers returning from a Broadway performance. “There was never any doubt in my mind that I was going to pitch,” said Hallahan, who hid the injury from Street. “It was an important game and I wanted to be in it. Two fingers on my right hand were packed in some sort of black salve and I had to cut my glove so that they could protrude on the outside.”21 Hallahan pitched a no-hitter through seven innings and battled Vance for nine scoreless innings before center fielder Taylor Douthit scored the only run of the game on Andy High’s pinch-hit double in the tenth. Hallahan pitched another scoreless frame in the tenth to secure the win. More importantly it ended Brooklyn’s 11-game winning streak, moved the Cardinals into a dead heat with the Robins, and established Hallahan’s reputation as a big-game pitcher. The Cardinals swept the series, went 21-4 in September, and won their third pennant in five seasons. In the “Year of the Hitter,” Hallahan notched 15 wins (with 9 losses), started a career-high 32 times, posted an above-average 4.68 ERA, and led the league with 126 walks and 177 strikeouts. In an era when strikeouts were rare, NL pitchers struck out ten or more batters in a game nine times; Hallahan notched three of them.

The Cardinals faced the Philadelphia Athletics, the overwhelming favorites, in the World Series. Down two games to none, Hallahan tossed a seven-hitter, shutting out the slugging A’s while striking out six and walking five. In Game Six, with the Cardinals facing elimination, Hallahan lacked command of his pitches and surrendered two runs in the first inning on two hits and two walks. After pitching a scoreless second inning, but walking a batter and hitting another, he was lifted for a pinch-hitter in the third inning of the 7-1 loss.

Hallahan’s shutout in the World Series brought him increased attention, but he was not one to search for headlines. Preferring to spend his free time at a concert, play, or especially the movies, Hallahan was a modest, studious type. He was an avid reader, especially Wild West stories, and also enjoyed golfing. Throughout most of his career with the Cardinals, he lived with his parents in Binghamton and worked in the offseason at the Corona typewriter factory.

Lee Allen, former historian at the Baseball Hall of Fame, likened Hallahan to a left-handed version of Burleigh Grimes, and suggested that the lines at the side of his mouth gave him the impression of a bulldog.22 Always conscious of his appearance, the 5-foot-10 Hallahan was considered small for a power pitcher, and weighed just 170 pounds, but gave the impression of being smaller. Among teammates he was known as Moon, a nickname catcher Earl Smith gave him because of his round face accentuated by closely cropped blond hair, blue eyes, and pronounced ears. Other appellations were Pug and Lefty, but sportswriters preferred Wild Bill, or Sweet William when Hallahan pitched well.23

With a classic overhand delivery, Hallahan was primarily a fastball pitcher, but possessed a devastating hard curveball, and developed a deceptive slow curve as a change of pace which undoubtedly contributed to his success in 1930. “I simply threw the ball in there,” Hallahan said of his early career. “When I was in the hole, I had the impression that the soundest way to fool a batter was to cut loose with everything. I discovered that the slowballs are pretty effective when they aren’t expected.”24 Though Hallahan never overcame his wildness, he managed to control it enough to have a good run of success from 1930 through 1935, when he won a total of 85 games and averaged more than 200 innings pitched per year. “Bill Hallahan certainly has great speed,” said Ray Kremer, a standout pitcher for the Pirates in the late 1920s and early 1930s, but noted that his success resulted from the movement on his pitches. “[He] has a lot of stuff on the ball. The old ball certainly hops and shoots when Bill is having a good day.”25

In 1931 Hallahan reported early to camp in Bradenton in the best shape of his life and boldly predicted that the Cardinals would win the World Series.26 Before it was commonplace to train year-round, Hallahan was described as a “demon for condition” and was said to be “in the gym every day.”27 “Condition is 50 percent of a pitcher’s stock in trade,” he said. “All through spring training I chase fungoes to strengthen my legs, and after the season starts I’m always running.”28 Brimming with confidence and acknowledging manager Street’s patience in helping him develop into a staff ace, Hallahan overcame early-season control problems (22 walks in his first three starts) to have a dominating June. He tossed five complete games in six starts, won four of five decisions, and posted a 2.28 ERA in 51⅓ innings while issuing just 18 walks. He hurled consecutive shutouts when he held Brooklyn to six hits on June 7 and the Boston Braves to eight hits on June 13. On August 30 he struck out a career-high 13 in a convincing complete-game 4-1 victory against the Pirates. Concluding the season winning four of five starts, each victory a complete game, Hallahan finished with a career-high 19 wins to tie for the lead in the NL. Logging a career-high 248⅔ innings, Wild Bill led the NL in walks (112) and strikeouts (159) for a second straight year, and in wild pitches (11) for the first of three times.

St. Louis ran away with the pennant behind a scrappy, hard-nosed team led by MVP Frankie Frisch, 5-foot-8 rookie Pepper Martin, and veterans Chick Hafey and Jim Bottomley. Though they hit just 60 home runs, they scored the second most runs (815) in the league. The pitching staff was a model of consistency and ranked second in ERA. Hallahan led the team with 30 starts and innings; Burleigh Grimes, Paul Derringer, Rhem, and Syl Johnson each started at least 23 games, and Jesse “Pop” Haines started 17; all six won at least 11 games to help the Cardinals set a franchise record with 101 wins.

Overwhelming underdogs in a World Series rematch with the Athletics, the Cardinals pulled off one of the great upsets in baseball history by defeating the A’s in seven games behind Hallahan’s masterful pitching and Martin’s legendary hitting and base stealing. In Game Two, Wild Bill issued seven walks but limited the A’s to just three singles while striking out eight in a commanding 2-0 shutout in St. Louis. With the Series tied at two games apiece, Hallahan pitched another complete-game gem, limiting the A’s to one run on nine hits and one walk, and won 5-1 in Philadelphia. In the seventh game, evoking memories of Alexander’s relief of Haines in Game Seven of the 1926 World Series, Hallahan relieved the fading Burleigh Grimes in the ninth inning with St. Louis leading 4-2. Needing just one out and facing the go-ahead run at the plate, Hallahan induced a deep fly ball to center field from Max Bishop for the final out of the game and clinched the Cardinals’ second championship in five years. George Talbot of the Associated Press wrote, “[Hallahan has pitched] two of the greatest games in World Series history,” yet noted that Martin’s hitting and running (12-for-24 with five stolen bases) “have virtually overshadowed Hallahan’s Homeric hurling.”29

After a disastrous sixth-place finish in 1932, Street was replaced by player-manager Frankie Frisch after 91 games in 1933. The Redbirds were in transition with a crop of young players (pitchers Tex Carleton and Dizzy Dean, and fielders Ripper Collins, Leo Durocher, and Joe Medwick) gradually replacing veterans. Hallahan bounced back from an injury-plagued season in 1932 (though he posted a 12-7 record and a team-best 3.11 ERA) and hurled three consecutive complete-game victories to begin the 1933 campaign. Behind the pitching of Hallahan and Dean, the Cardinals battled the Giants for the lead through late June before slumping and playing inconsistently in the second half of the season. On July 4 Hallahan improved his record to 10-4 with a complete-game win over the Pirates in the Cardinals’ 72nd game, and appeared headed for a 20-win season. Often a victim of poor run support, Hallahan notched just six more victories and lost nine games (in which the Redbirds scored a total of 19 runs) to finish with a 16-13 record and a 3.50 ERA while matching career highs with 32 starts and 16 complete games for the fifth-place Cardinals.

Hallahan’s participation in one of the most historic games in baseball history, the inaugural All-Star Game played in Chicago’s Comiskey Park on July 6, 1933, is often overlooked. National League manager John McGraw, the newly retired boss of the New York Giants, named four pitchers to his staff: Carl Hubbell (11-5 at the All-Star break), Hal Schumacher (9-5), Lon Warneke (9-7), and Hallahan. In a surprise decision, he chose Hallahan to start the game to counter the left-handed sluggers on the AL squad. Hallahan was lifted in the third inning after walking Charlie Gehringer, surrendering a towering home run to Babe Ruth (whom he had struck out in the first inning) and walking Lou Gehrig. Charged with the loss, Wild Bill lived up to his name, issuing five bases on balls and surrendering three runs in two innings.

At 31, Hallahan was the veteran among the Cardinals’ five primary starting pitchers (Dizzy and Paul Dean, Carleton, and Bill Walker) for the legendary Gas House Gang in 1934. He struggled for most of the season, and his record dropped to an unsightly 4-12 with an ERA of 5.05 after a 9-2 loss to the Reds on August 7. In his next start, 11 days later, Hallahan pitched his best game of the year, a six-hit shutout of the Braves, to resurrect his season. Taking a back seat to the Dean brothers and Carleton, Hallahan pitched his best during the Redbirds’ exciting rush to the pennant, winning his last four decisions and posting a stellar 1.82 ERA. He finished the season with an 8-12 record and a slightly below league-average ERA (4.26). Called to rekindle his magic, Hallahan started Game Two of the World Series against the Detroit Tigers. He limited Mickey Cochrane’s sluggers to six hits, four walks, and two runs over 8⅓ innings before being replaced by Walker in a tie game that the Tigers eventually won 3-2 in 12 innings. Hallahan did not pitch again in the Gas House Gang’s exciting seven-game Series victory. Nonetheless, he proved to be one of the best World Series pitchers in Cardinals history. With a 3-1 record, including two shutouts, Hallahan posted a 1.36 ERA in 39⅔ innings for four pennant winners.

The 1935 season started off horribly for Hallahan. Shelled in his first two starts, he lost his spot in the rotation and was used sparingly through June, posting a dismal 6.52 ERA in 13 appearances for the inconsistent Cardinals. Beginning with a three-hit shutout over the Pirates on July 2, Hallahan commenced a streak of five consecutive complete-game victories helping propel the Cardinals from 9½ games back to just a half-game behind the Giants on July 22. Pitching more often than at any other time of his career, Hallahan made 27 appearances (19 starts) in the last three months of the season. (Only Dizzy Dean pitched more often.) During that stretch Hallahan won 12 of 16 decisions and posted a 2.57 ERA, but the Cardinals could not match the red-hot Cubs who won a major-league record 21 consecutive games in September to overtake the Cardinals and Giants and win the pennant. In his last year as an effective major leaguer, the 32-year-old Hallahan pitched in a career-high 40 games (23 starts) and posted an above-average 3.42 ERA for the second-place Cardinals.

Hallahan’s contract dispute and holdout prior to the 1936 season preceded another ineffective start to the season. Cardinals owner Sam Breadon, renowned for jettisoning his players before they lost value, did not make an exception for Wild Bill. With a 2-2 record and an unsightly 6.38 ERA, Hallahan was sold to the Cincinnati Reds on May 31. The remaining 2½ years of his career were occasionally highlighted by reminders of his once powerful fastball, but were more often filled with frustratingly ineffective outings. In a season and a half with the second-division Reds, Hallahan won just 8 times, lost 18, and posted a 4.91 ERA. Relegated to a rarely used reliever and occasional starter with a 6.14 ERA in 1937, Hallahan was released by the Reds on February 3, 1938.

Former Cardinals catcher Jimmie Wilson, in his fifth season as player-manager for the woeful Philadelphia Phillies, was instrumental in his team’s decisions to sign the 35-year-old Hallahan. After all the success with the Cardinals, Hallahan endured his second consecutive last-place finish as the Phillies won only 45 times the entire season. With ten starts among his 21 appearances, Hallahan seemingly turned back the hands of time on August 25. He pitched all 11 innings to defeat the Pittsburgh Pirates, 2-1, his only victory of the season and the last game of his big-league career. Before 3,093 fans at Forbes Field, Hallahan needed just 2 hours and 25 minutes to pitch his last complete game. At the end of the season, the 36-year-old veteran was released.

Hallahan signed with the Minneapolis Millers of the American Association but was released after an abbreviated tenure (five games), bringing his 16-year career in the majors and minors to an end. He won 102 games and posted an above-league-average 4.03 ERA in his 12-year big-league career. He won 62 games in the minor leagues. For all of his unsettling wildness, Wild Bill hit only eight batters in the majors. He was a fiercely competitive pitcher who wanted to pitch the big game. “[Hallahan] was a truculent guy who used to stalk onto the field with his glove jammed into his hip pocket and a big wad of tobacco in his cheek,” reminisced Hall of Fame historian Lee Allen.30

In retirement, Hallahan returned to Binghamton with his wife, Marion Teresa (Forbes) Hallahan, and their daughter, Mary. In 1942 he was inducted into the Army and was stationed at Fort Niagara, New York. For more than 20 years he worked as a supervisor for General Aniline and Film Company (GAF) in Binghamton. Always ready to talk about baseball to anyone interested, Hallahan regularly participated in Cardinals reunions and occasional old-timers games. For decades after Hallahan’s playing career was over, his name was invoked to describe hard throwers in the Cardinals organization, like Max Lanier, Johnny Grodzicki, and Bob Gibson, and also those who fought to control their stuff.

After a battle with cancer, Bill Hallahan died on July 8, 1981, at the age of 78. He was buried at Calvary Cemetery in Johnson City, New York, just a few miles from his hometown. “One nice thing about baseball,” Hallahan once said matter-of-factly, “you’re remembered for the successes you’ve had rather than the failures.”31 Wild Bill had his share of successes.

Bill Hallahan player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York

Ancestry.com

BaseballLibrary.com

Baseball-Reference.com

New York Times

Retrosheet.org

The Sporting News

Notes:

1] Clifford Bloodgood, “ ‘Wild Bill’ Becomes ‘Sweet William,’ ” Baseball Magazine, July 1932, 297.

2 The Sporting News, January 1, 1931, 7.

3 “Hallahan Proves a Great Pitcher,” undated article in Hallahan’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

4 The Sporting News, May 25, 1933, 2.

5 “Talent That Is Complicated,” Monitor-Index and Democrat (Moberly, Missouri), June 6, 1940, 6.

6 The Sporting News, January 1, 1931, 7.

7 “Young Southpaw Shows Rickey Stuff,” San Antonio Light, March 4, 1925, 12.

8 “Young Southpaw.”

9 The Sporting News, January 1, 1931, 7.

10 “Hallahan Big Show” (Associated Press), Kingsport (Tennessee) Times, March 12, 1926, 12.

11 The Sporting News, May 25, 1933, 2.

12 Paul W. White, “New York Carping Critics Claim Cardinals Exceedingly Nervous,” Portsmouth (Ohio) Daily Times, October 1, 1926, 28.

13 “Haid and Morrow, Star Battery in First Game,” Syracuse Herald, April 12, 127, 19.

14 The Sporting News, November 1, 1928, 7.

15 “Cardinal Scout Is Quite Enthusiastic,” Akron Register Tribune, December 20, 1928, 2.

16 “Bill Hallahan. Cardinals,” Waterloo (Iowa) Evening News, March 15, 1929, 18.

17 “Ready to Thank Pancho Snyder for His Success,” (NEA Service), Lima (Ohio) News, April 5, 1929, 27.

18 John Kieran, “Sports of the Times,” New York Times, October 1, 1930, 40.

19 The Sporting News, May 25, 1933, 2.

20 “Cards Fans Flock to Wild Bill Hallahan,” (AP), Meriden (Connecticut) Daily Journal, October 4, 1930, 4.

21 Richard Peterson, St Louis Baseball Reader (Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press, 2006), 161.

22 The Sporting News, October 12, 1968, 68.

23 The Sporting News, May 25, 1933, 2.

24 Clifford Bloodgood, “ ‘Wild Bill’ Becomes ‘Sweet William,’ ” Baseball Magazine, July 1932, 298.

25 Ray Kremer, “Pitching From a Veteran’s Viewpoint. Comprising an interview with Ray Kremer,” Baseball Magazine, July 1932, 347.

26 Sam Murphy, “Hallahan Sees Cards as Champs,” Appleton (Wisconsin) Post-Crescent, January 8, 1931, 12.

27 “Hallahan Sees.”

28 Clifford Bloodgood, “’Wild Bill’ Becomes ‘Sweet William’,” Baseball Magazine, July 1932, 298.

29 George Talbot, “Bill Hallahan’s Wonderful Pitching gets Sidetracked,” (AP), Lewiston Evening Journal (Lewiston, Maine), October 8, 1931, 10.

30 The Sporting News, October 12, 1968, 68.

31 Richard Peterson, St. Louis Baseball Reader, 159.

Full Name

William Anthony Hallahan

Born

August 4, 1902 at Binghamton, NY (USA)

Died

July 8, 1981 at Binghamton, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.