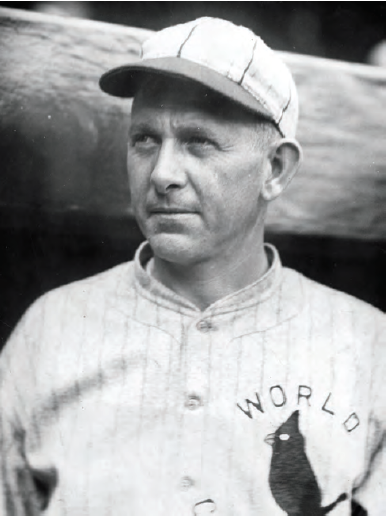

Jesse Haines

The only St. Louis Cardinal to play on the first five National League pennant winners in franchise history (1926, 1928, 1930, 1931, 1934), Jesse “Pop” Haines was a 26-year-old “rookie” when he debuted for the Redbirds in 1920. He was a three-time 20-game winner and pitched for the Cardinals for 18 consecutive seasons before retiring at the end of the 1937 season at the age of 44 as the big leagues’ oldest player. With 210 wins, he was elected by the Veterans Committee to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1970.

Jesse Joseph Haines was born on July 22, 1893, in Clayton, Ohio, near Dayton, the youngest of the five children of Elias and Althea Haines. Five years later his father, an auctioneer and carpenter, moved the family to a farm in Phillipsburg, five miles from Clayton. For the remainder of his life, Jesse called the small Midwestern town home. “I played baseball from the time I can remember,” Haines said. “[We] played with a hard rubber ball, a dime bat, and a quarter glove.”1 Haines pitched on his grammar school team, quit school after the eighth grade in 1907 to become a well driller with his oldest brother, and started to pitch for the town team in Phillipsburg, the All-Stars. “I had ambitions to become a professional,” said Haines.”2 All big leaguers were heroes. We collected those little cards with pictures of ballplayers on them,” he recalled. “Those cards were about the only way we ever got to see what a player looked like.”3 Raised by “honest, wholesome, God-fearing” parents who objected to playing baseball on the Sabbath, Jesse hid his uniform in a neighbor’s corncrib to pursue his passion.4 In Dayton, about 20 miles southeast of Phillipsburg, the fair-skinned, blond-haired Haines played semiprofessionally for Standard and later National Cash Register in 1912, and then for Lily Brew in 1913 when he was invited to pitch one game (a ten-inning, complete-game loss) for the Dayton Veterans of the Class B Central League.

In his first full season of professional baseball in 1914, the 21-year-old Jess, as he was known during his playing career, embarked on a grueling and frustrating six-year odyssey which included injuries and league closings with stops at at least eight minor-league teams, tryouts with major-league clubs, and a return to semipro ball before securing a permanent spot on the St. Louis Cardinals in 1920.

Signed by player-manager Harry Martin of the Fort Wayne Railroaders in the Class B Central League for a salary of $135 per month in 1914, Haines pitched just twice before breaking his finger in batting practice.5 Shunted off to the Saginaw Ducks in the Class C Southern Michigan League, Jess won 17 games, logged 258 innings and led the Ducks to the league title by pitching a ten-inning complete game in the final of the championship series.6 “In the minor leagues you were lucky to get paid at all,” said Haines, whose salary dropped to $115 per month with the Ducks.7 “But I wanted to play so badly that the salary meant but little to me.”8 Back with Saginaw in 1915, Haines got off to a good start and tossed a no-hitter against the Flint Vehicles in June.9 When the league disbanded on June 29, Haines was signed by the Detroit Tigers. On the Tigers roster for two months but not seeing action in an official game, Haines was strictly a batting-practice pitcher and may have suffered from diphtheria, causing weakness.10 Frustrated by his lack of playing time, Haines often credited Ty Cobb with giving him inspiration to forge ahead with his career. “Say, kid, you’ve got something on that fastball. It’s hard to follow and some day they’re going to reading about you,” the Georgia Peach reportedly told him.11

Expecting an invitation to the Tigers’ spring training in 1916, Haines was disappointed to be assigned to the Springfield (Illinois) Reapers in the Central League. He won 23 games for Springfield, prompting rumors that he’d be called up to the Tigers. In the offseason he was sent to the Denver Bears of the Class A Western League, but was unexpectedly returned to Springfield to start the 1917 season.12 Described as a “star pitcher” by Sporting Life, Haines notched 19 wins in 1917, but found himself in limbo again when the league folded at the end of the season.

Haines may have experienced his most taxing season in professional baseball in 1918. Signing with the Topeka Kaw-nees of the Class A Western League (the team relocated during the season 170 miles to the southwest in Hutchinson, Kansas, and was known as the Salt Packers), Haines pitched for Johnny Nee, his former manager during his one-game career with Dayton in 1913. With a 12-4 record in midseason, Haines was purchased by the Cincinnati Reds. He reported to manager Christy Mathewson’s team and made his major-league debut against the Boston Braves on July 20 at Redland Field. In relief of Pete Schneider with bases loaded and no outs in the fifth inning, Haines put out the fire and surrendered five hits and one run over five innings in an 8-3 defeat.

Released by the Reds shortly after his promising debut, Haines returned to Phillipsburg and contemplated quitting baseball. George Textor, player-manager of Agathon Central Steel, a semipro team in Massillon, Ohio, persuaded Haines to join his team.13 An “unconquerable twirler” for Agathon, Haines parlayed his success into a contract with the Tulsa Oilers in the Class A Western League. With an unsightly 5-9 record and 4.19 ERA, he was sold by Tulsa in midseason to the Kansas City Blues of the Double-A American Association. Haines won 21 of 26 decisions in a remarkable turnaround to his season, indeed his career. The “best pitcher” in the league,14 Haines drew the interest of a number of big-league teams despite breaking his ankle against Indianapolis on September 4.15

“St. Louis Put Over the Real Big Deals,” reported The Sporting News about the Cardinals acquisition of Haines.16 The perpetually cash-strapped Redbirds, who had enjoyed just three winning seasons since 1900, were a team in transition at that time. Branch Rickey took over as manager of the club in 1919 and borrowed $10,000 from local banks to take a chance on Haines. Stepping down as team president in 1920 when Sam Breadon purchased majority ownership in the team, Rickey remained at the helm but realized that the Cardinals could never compete financially with the richer teams. Consequently, he developed baseball’s first farm system, and Jess Haines was the last player he ever bought.

Though Haines is remembered as a knuckleball pitcher, he began his career as a fastball-curveball pitcher. In his first start with the Cardinals, on April 17, 1920, the 26-year-old rookie held the Pittsburgh Pirates scoreless for 12 innings at Robison Field in St. Louis before giving up three runs in the 13th inning and losing the game, 3-0. He won the first of his 210 games for the Cardinals on May 6 when he shut out the Reds in St. Louis. (The Cardinals moved to Sportsman’s Park on July 1, 1920.) Durable, the big, 6-foot, 190-pound Haines, started 37 games, completed 19, and led the NL with 47 appearances. “Hard-luck Haines” concluded the season with his career-high 20th loss in an epic duel with Pete Alexander at Cubs Park in Chicago on October 1. After surrendering two runs in the first five innings, Haines tossed 9⅔ consecutive no-hit innings (from the seventh to the 16th) before giving up a one-out run in the 17th to lose, 3-2. Alexander pitched a career-best 17-inning complete-game to earn the victory. Haines finished the season with a career-high 301⅔ innings for the 75-79 Cardinals.

“I soon found out I would have to have something [besides a fastball and curve], if I wanted to stick around long,” said Haines, who followed up his promising rookie year by going 18-12 in 1921 and 11-9 in 1922 with an ERA slightly above league average each season.17 With his fastball losing effectiveness and his hits per nine innings steadily rising, Haines began working on a knuckle ball. He credited Philadelphia A’s pitcher, Eddie Rommel, the first big leaguer to use the knuckleball extensively, for teaching him the pitch. Unlike Rommel, who gripped the pitch with tips of his index and middle fingers, Haines gripped the ball with the first knuckles on his index and middle fingers with the ball resting against the inside of his ring finger.18 The result was a hard knuckler that came straight down and did not flutter like Rommel’s. “[My knuckler] acted like a spitball,” said Haines. “I had very good control of it and threw it from different positions.”19 Even though Haines developed calluses on his knuckles because of the friction the ball caused, his knuckles had a tendency to bleed.

Adding the knuckleball to his pitching arsenal in 1923, Haines had his best season to that point. After finishing in third place in 1921 and tied for third in1922, the Cardinals slipped to fifth at 79-74 in ’23, but it was no fault of Haines. He led the team in wins (20), innings (266), complete games (23), and ERA (3.11). He celebrated his 30th birthday by shutting out the Reds on four hits en route to completing 11 of his next 16 starts and winning ten of them.

The Cardinals and Haines took sudden and unexpected steps backward in 1924. Despite a potent offense with Jim Bottomley and Rogers Hornsby (who batted .424), the Redbirds limped to a sixth-place, 65-89 record primarily due to poor pitching. In 31 starts Haines won just 8 games, lost 19, and notched a 4.41 ERA, well over the league average. Teams batted .309 against him. The following season, on a better Cardinals team, Haines won 13 of 27 decisions but his ERA rose to 4.57, and he started just 25 times.

Ironically, Haines pitched his only big-league no-hitter during his worst season. On July 17, 1924, he held the Boston Braves hitless at Sportsman’s Park in a 5-0 win. It was the first no-hitter in St. Louis baseball history since George Washington Bradley pitched the first one for the St. Louis Brown Stockings in 1876, the inaugural season of the National League. “I had almost perfect control,” said Haines of his game. “There was nothing special about my speed. I started as I always do — trying the corners with my curve on the outside to right-handed hitters and keeping the fast one close to the handle of the bat.”20

A quiet, conscientious, humble, and serious person, Haines neither smoked nor drank, and eschewed the night life. He preferred life in the small town to the hustle and bustle of the big city. During the offseason, he lived with his wife, Carrie (Weidner) Haines, a Phillipsburg resident whom he married in 1915. They had one child, a daughter, Juetta Lou, born in 1925. For many years, Haines operated an auto garage with one of his brothers.

Easygoing off the field, Haines was described as a “clean sportsman, who has never taken advantage of a rival batter with an intimidating cranial shot.”21 But he was also a fiery and fierce competitor who took losing hard. Throughout his career, he was known for chewing out teammates for mental lapses, careless throwing errors, or a perceived lackadaisical approach to the game. Haines’s hard-nosed attitude, his dedication to the game, and his desire to win impressed the equally competitive Hornsby, who took over the helm of the Cardinals in 1925 when Rickey was replaced as the field manager after 38 games.

By 1926 sportswriters and fans began to wonder whether the 32-year-old Haines had lost it. His fastball lacked zip, his knuckleball vanished, and he was no longer considered the staff ace.22 But Hornsby was committed to Haines and named him to start the second game of the season, at home against the Pirates on April 14. When Pirates catcher Earl Smith hit a liner back to the mound leading off the third inning, it hit Haines on the instep near his right ankle. Haines fell to the ground, was removed from the game, and the team feared his ankle was broken. X-rays proved negative, but Haines pitched sporadically over the next nine weeks with only one start and 11 relief appearances. Led by Flint Rhem and Bill Sherdel, the Cardinals remained in the pennant race and were tied with the Pirates a half-game behind the Reds when Haines rejoined the starting rotation on June 19. In a dramatic return, Haines shut out the Braves on seven hits. Over the next three months he anchored the Cardinals’ staff and was arguably the hottest pitcher in the NL, posting 10 wins and completing 13 of 18 starts with three shutouts in one of the best stretches of his career. After a nerve-racking race with the Pirates and Reds, the Cardinals, who played their final 24 games on the road, captured their first pennant despite losing five of their last seven games.

Haines attributed his new-found success and rebirth in 1926 to two pitches. “Thought I had [the knuckler] in 1923, but it eluded me the next years. Not until midsummer 1926 did the mystery of it come back to me,” he said. “And then I started to throw a slow ball. That helped me as much as the knuckler.”23

Haines’s pitching in the 1926 World Series against the overwhelming favorite New York Yankees has been overshadowed by Babe Ruth’s baserunning blunder (he was caught stealing in the ninth inning of Game Seven of a 3-2 game to end the Series) and by Pete Alexander’s dominating performance (two complete-game victories, and his famous save in Game Seven). After pitching an inning of scoreless relief in Game One, Haines limited the Bronx Bombers, blanked only three times during the regular season, to just five singles in a dominating shutout in Game Three, wining 4-0. In the fourth inning, Haines belted a two-out, two-run homer, his first since 1920, and one of four in his career. Given the start in Game Seven, Haines held the Yankees to two runs over 6⅔ innings. With his knuckles bleeding so profusely that he had a difficult time gripping the ball, Haines surrendered eight hits and issued five walks before giving way (with the bases full) to Alexander, who preserved Haines’s victory for the Cardinals’ first World Series championship.

With a cerebral approach to pitching, Haines altered his pitching motion and delivery as he aged. When he pitched semipro ball in Massillon, his delivery was described a “deceptive” and his pitches were faster than they seemed.24 “I was wild for years,” said Haines, “wilder than Bill Hallahan ever was” (referring to his Cardinals teammate nicknamed Wild Bill25). Haines was a strict overhand pitcher when he arrived in St. Louis, but Rickey suggested he alter his motion to overcome bouts of wildness.26 Consequently, he began to pitch side-arm to three-quarters. His short, rhythmic delivery put little stress on his shoulder and arm, and undoubtedly helped him play until after his 44th birthday.

The world champions experienced a tumultuous offseason. Hornsby, involved in a contract dispute, was traded in late December to the New York Giants for second baseman Frankie Frisch and pitcher Jimmy Ring. Haines held out, demanding a “substantial increase in salary,” reportedly a $5,000 increase to $12,500.27 After signing in time to participate in spring training in Avon Park, Florida, the 33-year-old began the season by tossing a two-hit shutout against the Cubs in Chicago, and won his first five starts, all complete games. Haines led the league with 25 complete games and six shutouts (both career bests), and was used only twice in relief all season. On three occasions he tossed extra-inning complete-game victories (13 innings against the Cubs on June 21 and the Reds on September 26, and 11 innings against the Pirates on August 12) en route to 300⅔ innings. He also set personal bests with 24 wins and a 2.72 ERA. With the 40-year-old Alexander (21-10), Haines formed the most formidable pitching duo in the NL, but it was not enough to overcome the Pirates, who won the pennant by 1½ games over the Redbirds.

Under new manager, Bill McKechnie (the team’s fourth different Opening Day skipper in as many years), the Cardinals got off to a slow start (10-11) in 1928 before the offense, led by MVP Bottomley (31 HRs, 136 RBIs, .325 BA) and Chick Hafey (27, 111, .337), woke up. Continuing his success from 1927, Haines hurled ten complete games in his first 12 starts. By the end of July it appeared as though the Redbirds would run away with the pennant, but after a poor August (14-13) they were in a tight race with the New York Giants, who went 25-8 during September. At his best when the Cardinals needed him the most, Haines pitched complete games to win his last eight starts and help lead the Cardinals to their second pennant. Completing 20 of 28 starts, Haines won 20 games and notched a 3.18 ERA. In a rematch of the 1926 World Series, the Yankees swept the Cardinals, defeating 21-game-winner Bill Sherdel in Games One and Four, Alexander in Game Two, and Haines in Game Three. Given a two-run lead after one frame, Haines surrendered a towering solo home run to Lou Gehrig in the second inning and then a two-run inside-the-park home run to him in the fourth. Haines was undone by two errors by his catcher that led to three unearned runs in the sixth inning, and departed after six innings having surrendered six hits and three walks during a 7-3 defeat.

Haines’s 1929 season was a study in contrasts. A complete-game win against the Reds on May 20 gave him his 14th consecutive win over two seasons. Notching his ninth victory of the season on June 22, Haines appeared headed to a third consecutive 20-win season, but then encountered the worst slump of his career. He won just four more times, posted an unfathomable 8.00 ERA over his final 84⅓ innings, lost control of his knuckleball and his spot in the rotation. The Cardinals pitching staff, the oldest in the major leagues, fell apart. Sherdel (10-15, 5.93), Haines (13-10, 5.71), and Alexander (9-8, 3.89) seemed to be on their last legs. In disarray all season, with three different skippers, the reigning pennant winner finished in fourth place.

By the start of the 1930 season, newspapers began making more references to Haines’s age. “[Haines] has gone rapidly downhill” said an Associated Press report;28 “[Haines] slip[s] out of star class,” announced another headline.29 Gabby Street, the Cardinals’ fifth different Opening Day skipper in the last six years, still had confidence in his 36-year-old starter. Given five or more days of rest in 15 of his 24 starts, Haines rebounded to post 13 wins (tied with 36-year-old spitballer Burleigh Grimes, a newcomer to the Cardinals and his roommate, for second on the team) and led the team with 14 complete games. Sluggish almost the entire season, the Cardinals caught fire, going 44-13 the last two months of the season. In fourth place on Labor Day, 6½ games out of first, they overtook the Cubs, Brooklyn Robins, and Giants in the final two weeks of the season in an exciting four-team race. Reminiscent of 1928, Haines pitched his best at the most crucial time of the season, winning his last six decisions (in seven starts). Haines enjoyed his final dramatic moment on the national stage against Connie Mack’s heavily favored Philadelphia Athletics in Game Four of the World Series in St. Louis. Facing Lefty Grove, the era’s best pitcher, with the Cardinals down two games to one, the big right-hander tossed a complete-game four-hitter (all singles). In the third inning Haines tied the game with an RBI single in the remarkable 3-1 victory. However, three days later, the A’s won Game Six to claim their second consecutive championship.

Throughout his career, Haines was a fast worker on the mound. His victories over Grove and the A’s and his shutout of the Yankees in 1926 lasted just 1:41. “You get the heebie-jeebees if you are out on the mound too long,” said Haines, who rarely had discussions with his catcher during a game. “When you take too long pitching, you think about pitching one way and then change your mind. And then you end up not doing it either way you planned.”30

Three weeks in the thermal waters at Hot Springs, Arkansas, prior to camp must have worked wonders on Haines’s creaking body. He began the 1931 season by winning five of his first six starts with four complete games. But when he was hit in the right wrist on June 9 by a line drive from the Robins’ Babe Herman, he missed a month. Returning to the starting rotation on July 10, he won six of eight starts, including two shutouts and four complete games, and notched an impressive 1.65 ERA in 60 innings, enabling the Cardinals to run away with the pennant. He won 12 of 15 decisions, but his season, indeed his career, took a drastic turn when he injured his right shoulder on September 5 against the Pirates. Out for the remainder of the season and missing the Cardinals’ stunning upset of the heavily favored A’s in the World Series, Haines was never the same after the injury. It was his last season as predominantly a starter.

Haines’s shoulder injury appeared to signal the end of his career. He logged just 85⅓ innings in 1932 in 20 appearances (10 starts) and struggled. But he returned in 1933 and transformed himself into a valuable reliever and occasional starter for the remainder of his career. From 1933 to 1936, he averaged 31 appearances (9 starts) and 105 innings per year, but his importance to the Cardinals extended far beyond his pitching. He was like a stern father-figure to a cast of new young players, among them hurlers Dizzy and Paul Dean, and Tex Carleton, and sluggers Joe Medwick and Johnny Mize. Teammates began calling him “Pop” because of his age, and papers often referred to him as “Papa Jess.” Above all, Haines had the respect of his teammates. He harkened back to a time before Rickey and Breadon had transformed the Cardinals into the National League’s most consistent team.

The Cardinals won their fifth pennant in nine years in 1934. The Gas House Gang, one of baseball’s most enduring teams, was led by player-manager Frankie Frisch and a host of scrappy, rough, hard-nosed players like Medwick, Ripper Collins, Leo Durocher, Pepper Martin, and the Dean brothers. The team’s brash personality was in stark contrast to Pop’s more austere and staid approach to baseball. Haines led the team with 31 relief appearances (he started six times) and provided veteran leadership. In the Cardinals’ exciting World Series championship over the Detroit Tigers, Haines pitched just once, two-thirds of an inning of mop-up duty in Game Four loss. In his World Series career, Haines won three of four decisions and posted a minuscule 1.67 ERA.

The Cardinals under Rickey and Breadon had a reputation of getting rid of their star players at the first sign of age or slippage, but they kept Haines well past his peak years. “I could have earned $4,000 or $5,000 more with the Giants or Cubs in my best years,” said the intensely loyal Haines, “but then I don’t think I would have lasted as long as I have.”31 Haines returned for his 18th consecutive season with the Cardinals in 1937, at the time an NL record for longest continuous service with one club. In a gesture of respect and recognition of Haines’s career, Bill Terry, manager of the NL All-Star squad, named him an honorary coach of the team. Haines was pressed into the starting rotation after the All-Star Game and tossed a complete-game six-hitter to defeat Brooklyn on July 23, one day after his 44th birthday. In his next start he hurled another complete-game victory against the Dodgers. They were the final two wins in his career. “It’s not my arm that’s given up on me. It’s my legs,” he said. “After four or five innings they start wobbling.”32 By mutual agreement, the Cardinals released Haines at the end of the season.

“Old Jess” retired with 210 wins, 158 losses, 208 completes games, and 3208⅔ innings pitched in his 19-year big-league career. He won 107 games in his seven-year minor-league career.

In 1938 Haines was the pitching coach for the Brooklyn Dodgers, skippered by Burleigh Grimes. He returned to Phillipsburg the following year and served as the Montgomery County auditor for 28 years before retiring.33 A country gentleman and farmer at heart, Haines did not miss the bright lights of the city or excitement of the stadium. “They’d never get my name on a baseball contract (today),” Haines said in retirement. “As much as I loved the game — loved to walk out there and challenge the hitters — I just couldn’t take all that big-city noise.”34

Haines received baseball’s highest honor in 1970 when he was elected by the Veterans Committee to the Baseball Hall of Fame. However, his election is now seen as controversial. Frankie Frisch was the chair and major voice of the Veterans Committee during a notorious period in the early 1970s. Supported by Bill Terry and two sportswriters, Fred Lieb and J. Roy Stockton, Frisch successfully led efforts to have former teammates (Dave Bancroft, George Kelly, Haines, Chick Hafey, and Ross Youngs) enshrined. Historians have since then questioned the credentials and Hall-worthiness of these players.

After a long bout with cancer, Jesse Joseph Haines died at the age of 85 on August 5, 1978, in Dayton. He was buried at Bethel Cemetery in his hometown of Phillipsburg. Once asked to explain his longevity, Haines had a simple answer: “Get eight hours of sleep every night, watch what you eat, lay off the alcohol, and throw the ball where you’re looking.”35

Jesse Haines player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York

Ancestry.com

BaseballLibrary.com

Baseball-Reference.com

New York Times

Retrosheet.com

The Sporting News

Notes

1] Harry Brundidge, “Jesse Haines, Cardinal Pitcher, Used to Hide His Ball Suit in Corncrib,” St. Louis Star, June 12, 1926, 3.

2 Ibid.

3 Ed Rumill, “They never get Jesse Haines to sign today,” Christian Science Monitor, September 13, 1972 [no page number]. Jesse Haines player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

4 Ibid.

5 “The Central League,” Sporting Life, December 20, 1913, 15; Ernest Lanigan “Baseball Beginnings. Jesse Joseph Haines” (Associated Press), unnamed, undated publication, Jesse Haines player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

5] Ibid.

6 Sporting Life, October 31, 1914, 15.

7 Rumill.

8 Eugene F. Karst, director of information, “Jess Haines Had Another Great Year,” St. Louis Cardinals press release, January 15, 1928. Jesse Haines player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

9 Sporting Life, July 17, 1915, 63.

10 Unnamed article with no date and page, Jesse Haines player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

11 Ibid.

12 John H. Farrell, “Official Notice of Players Signed, Released, and Suspended in All Leagues of the National Association,” Sporting Life, November 11, 1916, 9.

13 Massillon (Ohio) Evening Independent, August 10, 1918, 10.

14 The Sporting News, February 19, 1920, 2.

15 Hutchinson (Kansas) News, September 4, 1919, 3.

16 The Sporting News, February 19, 1920, 2

17 Eugene F. Karst, director of information, St. Louis Cardinals Press Release. 1929. Jesse Haines player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

18 Neil Russo, “Batters Knuckled Under to Haines and Schultz,” September 6, 1964, Jesse Haines player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

19 Ibid.

20 Billy Evans, “Hitless Hero Says Good Control Gave Him Record Game,” Olean (New York) Times, September 17, 1924, 7.

21 The Sporting News, January 18, 1934, 6.

22 The Old Scout, “Pitcher Haines Runs Up Record in Long Service,” November 6, 1936. Jesse Haines player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

23 Eugene F. Karst, director of information, St. Louis Cardinals Press release, 1928. Jesse Haines player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

24 Massillon Evening Independent, August 19, 1918, 7.

25Brundidge.

26 Ibid.

27 World Series Pitching Star Hold Out for Redbirds,” (Associated Press), unnamed, undated publication. Jesse Haines player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

28 “Chances of St. Louis Cards for Pennant Are Not so Hot,” Burlington (North Carolina) Daily News, March 13, 1930, 10.

29 Philip Martin, “In the World of Sports,” McIntosh County Democrat (Checotah, Oklahoma), January 13, 1930, 10.

30 The Sporting News, February, 1968, 31.

31 Paul Thomas Dix, “ ‘Pop’ Haines Satisfied with 25-Years’ Work” (United Press), November 6, 1936. Jesse Haines player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

32 Bill Corum, “Jesse Joseph Haines Come Up to Forty-four and Looks Back 18 Years,” New York Journal-American, July 19, 1937, Jesse Haines player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

33 The Sporting News, February, 19, 1977, 38.

34 Rumill.

35 Mike Eisenbath, The Cardinals Encyclopedia (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1999), 201.

Full Name

Jesse Joseph Haines

Born

July 22, 1893 at Clayton, OH (USA)

Died

August 5, 1978 at Dayton, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.