Ray Murray

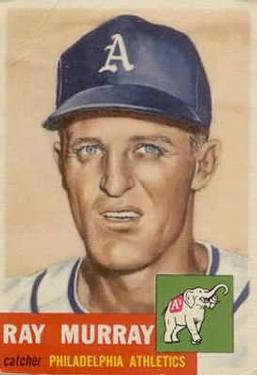

At least 23 major-leaguers have been nicknamed “Deacon” as of 2022, all but two of whom debuted before 1952.1 So, it was not Ray “Deacon” Murray’s sobriquet that made him stand out during a big-league career spanning all or parts of six seasons (1948, 1950-1954) with the Cleveland Indians, Philadelphia Athletics and Baltimore Orioles.

At least 23 major-leaguers have been nicknamed “Deacon” as of 2022, all but two of whom debuted before 1952.1 So, it was not Ray “Deacon” Murray’s sobriquet that made him stand out during a big-league career spanning all or parts of six seasons (1948, 1950-1954) with the Cleveland Indians, Philadelphia Athletics and Baltimore Orioles.

Instead, his antics and unique personality made him a memorable teammate and fan favorite, particularly in Texas, the state where he played or managed for 11 years in the minors. The year after Murray took his final professional at-bat, a newspaper described him as “One of the finest catchers and most popular figures in Texas League history.”2

Raymond Lee Murray was born on October 12, 1917, in Spring Hope, North Carolina. His parents, J. Atlas and Edna (Strickland) Murray had 10 children.3 Ray was third overall, as well as the third of five brothers. Atlas was a farmer, and the family was of Irish and Scottish ancestry.

Spring Hope, about 40 miles northeast of Raleigh, comprises just 1.5 square miles in Nash County. The town’s population – 1,221 in the 1920 census – remained nearly the same a century later. Little is known about Murray’s life before baseball. Army enlistment records note that he attended high school for four years, though the name of the institution is unclear. When he registered for the military draft a few days after his 23rd birthday, Murray described himself as a self-employed farmer.

In 1938, Murray played semipro baseball in the Southside Virginia League for a team based in Emporia.4 (Emporia, Virginia is less than 70 miles north of Spring Hope.) Back in North Carolina the following year, the Raleigh News and Observer reported that he caught for the New Hope club in the Wilson County League in June.5 Later that summer, the Rocky Mount Telegram mentioned a 4-for-4 performance on August 28 by Raymond Murray, the “new first baseman” for the Oak Level squad in the Nash County League.6

In 1940, Murray made his professional debut in the Class D Eastern Shore League (ESL). Later, he named his manager with the Pocomoke City (Maryland) Chicks, John “Pop” Whalen, as the person most responsible for his baseball career.7 The Chicks finished last with a 50-75 record.8 In 90 games – 56 as a catcher – Murray batted .263 with two homers and led the league with 20 sacrifice hits.9

Murray gained the nickname “Deacon” that summer. “When I was a kid I used to go to revival meetings. Just to pass the time, I memorized what the preacher said. After a while, I had a pretty good spiel of my own,” he said. “I don’t mean to poke fun at what they say. It’s just how they say it.” On team bus rides, he would deliver his “sermon” in a loud voice while waving his arms. “The guys got a kick out of it. One time they rigged up a microphone on top of the truck and drove it around Pocomoke City with me preachin’!”10

Pocomoke City’s franchise folded before the 1941 season and the president of the minor leagues, Judge William G. Branham, declared 10 Chicks players to be free agents. Murray wound up with the Tarboro (North Carolina) Orioles of the Class D Coastal Plain League shortly after the team hired Whalen to manage.11 Meanwhile, Murray’s older brother Hilliard landed with the ESL’s Salisbury Cardinals and went 10-12 to tie for that team’s lead in victories.12 (Hilliard never advanced above Class C.)

With Tarboro, Murray mostly played the outfield – Steve DeCubellis was the primary catcher. Murray, a 6-foot-3, 204-pound, right-handed batter and thrower, hit .322 in 75 games to pace the club’s regulars. At the conclusion of the season, the Baltimore Orioles of the Class AA International League (IL) purchased his contract, along with those of DeCubellis and first baseman Ed Sudol, the future major-league umpire.13

Murray was invited to the Orioles’ spring training in Hollywood, Florida. “Ray will hop nimbly aboard the Bird train at Raleigh. A special stop will be made for him.” noted the Baltimore Sun in March 1942.14 A few days later, the paper reported that he had made a good first impression on Baltimore manager Tommy Thomas. Its description: “Murray is a tall lad and strong. His feature is a rifle arm of deadly precision. He is fast afoot and can play a good outfield also.”15 However, the March 31 edition of the Sun said that Murray, suspecting he might be drafted into the Army, had requested permission to go home and clarify his status.16 Military records show that he was inducted into the service at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, on April 9.

Murray spent most of 1942-1945 at bases in Texas. He played ball for the Sheppard Field Mechanics in Wichita Falls, for example, a team that featured former big-leaguers Bob Neighbors, Dave Short, and Ray Poole.17 The archives of the Fort Worth Star-Telegram include a 1945 photo of Murray – described as a “slugging catcher” – wearing the uniform of the Fort Worth Army Air Fliers.18 While Murray was stationed in Fort Worth, he married Jacque D. Estill, the daughter of a custodian for a public school and a pork trimmer for a packing company. Their union produced two children, Ray Jr. and Jill, and lasted until her death in 2002.

Shortly after Murray was discharged from the Army Air Force, he detailed his service time as “3 yrs 9 mo 2 days 6 hrs 15 min.”19 World War II had caused him to miss out on his age 24 through 27 seasons in professional baseball.

When Murray finally joined the Orioles in 1946, the club was a Cleveland Indians affiliate, and the IL had been reclassified as Triple-A. He appeared in just 33 games for Baltimore as a backup to the more experienced Lou Kahn, though. When Cleveland sent rookie backstop Sherm Lollar down for more seasoning, Murray was optioned to the Oklahoma City (OKC) Indians of the Class AA Texas League.20

In OKC, Murray made a lasting impression with the way he reacted after losing track of a popup and letting it drop at his feet. “It was real embarrassing like,” recalled Ralph Houk, catcher for the opposing Beaumont Explorers years later. “Murray stood and looked at the ball for a minute. Then he kind of crouched down and walked around it like he was stalking it. All of a sudden, he pounced on it like a big cat, stuck the ball under his leg, dug a hole with his hands, shoved the ball in the hole and covered it with dirt. Then he kind of patted the dirt down, asked the umpire for a new ball and went back to catching.”21

Murray batted .254 with two homers in 42 appearances for a team that finished 44 games under .500. In December, the Orioles sold his contract to OKC.22 The next day’s Sun explained, “Ray was discovered to have a glaring batting weakness. And, unfortunately, he didn’t appear to be able to do anything about it.”23

In 1947, Murray returned to OKC and endured a frustrating slump. After he struck out to reach 0-for-12, he sprinted to left field, buried his bat in the pile of sand behind the fence at Texas League Park, and walked back to the dugout.24 When he grounded back to the pitcher to extend his stretch of futility to 0-for-26, he turned around halfway to first base, ran back home, and slid into the plate. “The umpire was an old guy,” Murray recalled. “He said, ‘What the hell are you doing? Are you trying to make a farce out of the game?’ I quipped, ‘If you had any guts, you’d call me safe.’”25 Overall, Murray hit a respectable .263 with nine homers and 57 RBIs in 122 games. He was selected for the All-Star team that faced league-leading Houston at midseason and, in the words of The Sporting News’s John Conley, was “generally regarded as the No. 2 catcher in the loop, a close second to Fort Worth’s former big leaguer, Ferrell Anderson.”26

Murray began the 1948 season in the majors as Cleveland’s third catcher, behind Jim Hegan and rookie Joe Tipton. He made his big-league debut at Briggs Stadium on April 25. pinch-hitting for pitcher Al Gettel after the Indians fell behind by three runs. Leading off the top of the third inning, Murray flied out to right against future Hall of Famer Hal Newhouser. The plate appearance was his lone action before he was optioned to the minors on May 15.27 Murray learned his fate a few hours after his wife joined him in Cleveland.28 The Indians’ Triple-A farm club in San Diego already had veteran catchers Len Rice, Hank Camelli, and John Ritchey, so Murray returned to OKC, where he “was met at the entrance gates by scores of teen age fans” who hadn’t forgotten how he had coached them in a YMCA program the previous summer.29

On May 30 in Chicago, Cleveland player-manager Lou Boudreau was reminded of the risks of carrying only two catchers on his roster. After Hegan departed for a pinch-hitter during an eighth-inning rally, Tipton batted for another player and was hit on the wrist by a pitch.30 Boudreau, who would earn AL MVP honors as a shortstop that season, had to catch the last two innings himself. The next day, Hegan caught all 18 innings of a doubleheader and OKC announced that Murray was returning to Cleveland.31 Murray remained on standby, however, until a two-for-one trade was executed on June 4 to open a roster spot.32 He played sparingly and was sent back to OKC on July 7 when the Indians promoted 42-year-old pitcher Satchel Paige to the majors.33

For OKC, Murray hit .297 with five homers in 64 games in 1948. When manager Pat Ankenman left the club briefly for family reasons, he named Murray the temporary skipper, and the team won two straight.34 Cleveland recalled Murray in September and he pinch-hit once on the final weekend of the regular season. He finished his first taste of the majors having gone 0-for-4 with three strikeouts in four appearances for the American League pennant winners, who went on to win the World Series.

The Indians acquired 35-year-old former All-Star Mike Tresh to back up Hegan in 1949. With Ritchey back behind the plate for his hometown team, Triple-A San Diego, Murray returned to OKC, where fans recognized his shouts and wails behind the plate that were heard throughout the circuit’s ballparks.35 Sometimes, he sang things like, “Swing that gal with the red dress on, some folks call her Dinah. Prettiest gal I ever saw and she comes from Carolina.”36

“I did most of that hill-billy singin’ when I was in the Texas League… Yes, I made a lot o’ noise in those days. I was a crazy sort,” Murray acknowledged.37 “Seems like I think best when I talk or sing… When I’ve got my mouth shut, I can’t think so well.”38

Since Murray called everyone “Brother,” he was “Brother” or “the Deacon” to his teammates.39 In 1949, he was also a major contributor to the league’s highest-scoring offense. OKC made the playoffs, and Murray batted .319 with 16 homers in 123 games, with career highs of 94 RBIs and 44 doubles.

In spring training 1950, Murray hit .319 with five homers.40 He made Cleveland’s roster as the number-two catcher. On April 20, he doubled against Detroit’s Ted Gray for his first major-league hit. Beginning with the second game of a May 14 doubleheader, Murray started a season-high nine straight games while Hegan was sidelined by an ailing back. During that stretch, Murray batted .367 (11-for-30), with a solo homer off the Yankees’ Eddie Lopat. But when Murray split his right thumb the following evening, Hegan returned to regular duty.41 Overall, Murray appeared in 55 games and batted .273 with one homer. In his 31 starts behind the plate, he caught victories for future Hall of Famers Bob Feller, Early Wynn, and Bob Lemon.

But Cleveland finished fourth despite a 92-62-1 record, and the Indians replaced Boudreau with Al Lopez in November. In December, 38-year-old Birdie Tebbetts was purchased from the Boston Red Sox to become Hegan’s chief backup. Murray opened the 1951 season as the Indians’ third-string catcher and got only one at-bat in April. It was no surprise when Murray was traded to the Philadelphia Athletics on April 30 as part of a seven-player deal involving three teams. Chicago White Sox outfielders Dave Philley and Gus Zernial, plus Cleveland lefty Sam Zoldak were also Philadelphia bound. The White Sox landed future Hall of Famer Minnie Miñoso from the Indians and outfielder Paul Lehner from the Athletics. Cleveland acquired Athletics southpaw Lou Brissie. Indians GM Hank Greenberg said Cleveland’s pennant chances were improved with Brissie, while the Evening Independent of Massillon, Ohio described Murray as a “husky 31-year-old long ball hitter” who had become dispensable.42

Murray did not display much power with the Athletics. Playing behind Tipton (until Tipton was waived in June 1952) and Joe Astroth, Murray went deep just once in 258 at-bats for Philadelphia over the next two seasons. His batting average declined from .220 in 41 overall games with two teams in 1951, to .206 in 44 contests in 1952.

Later, Murray traced his offensive struggles to closing his batting stance in an attempt to hit more homers. “What I want to do is play more… An’ hit more. I’m tryin’ hard,” he said at the beginning of the 1953 season. “I started working last winter an’ changing back to my old way of batting. It shows results. I used to be a good hitter before I started swinging for the fence.”43 After Astroth fractured his thumb on July 3, Murray received his best major-league opportunity.44 In 1953, he established personal big-league highs with 84 games (75 starts), a .284 batting average, 14 doubles, six homers, and 41 RBIs.

During Murray’s three seasons with Philadelphia, only about 40 percent of the runners that attempted stolen bases against him were successful.45 Among AL catchers who started at least 35 games, Murray produced the league’s second-best caught-stealing percentage in 1951, 1952, and 1953.46

Athletics lefty Alex Kellner finished with a 11-12 record in 1953, but he retroactively led the league in FIP (Fielding Independent Pitching).47 Murray caught 17 of his 25 starts that year, and Kellner remarked, “I’ve been working with him closer than with any other catcher.”48

At Griffith Stadium on May 23, Murray was ejected from a major-league game for the first time. “There was a rule in ’53 that said if you turn around and argue with the umpire you were automatically out of the game,” he explained. “So I had a card that I made up for the umpires. It read, ‘[Athletics manager] Mr. Jimmy] Dykes and I would like to know where that last damn pitch was.”49 Dykes was tossed by home-plate umpire Bill Grieve as well.

That offseason, Dykes moved on to the Baltimore Orioles, the new identity of the relocated St. Louis Browns franchise. On April 1, 1954 – less than two weeks before Opening Day – the Orioles purchased Murray for $20,000. Three days later, in Mobile, Alabama, the Orioles surrendered nine unearned runs in a 10-2 exhibition loss to the Chicago Cubs. In 1961, the Baltimore Sun’s Jim Ellis recalled that on the postgame bus ride, Murray told his new teammates, “Brothers. Don’t despair just because we let them sinful Cubs creep up like Satan and beat us today. Have faith, brothers, have faith in Brother [GM Arthur] Ehlers and Brother Dykes and we’ll all wind up happily in the kingdom of Baltimore. Glory, Hallelujah.” Murray then led the Orioles in the singing of “Throw a Nickel on the Drum.”50

After the regular season began, Murray helped the Orioles even their record at .500 (4-4) for what proved to be the last time in 1954 with a tie-breaking, RBI double off Billy Pierce with two outs in the top of the 10th at Comiskey Park on April 23. Two days later in the same ballpark, Murray cemented his reputation for flakiness by becoming “the only catcher ever thrown out of a game for praying!”51

Baltimore starting pitcher Joe Coleman had been ejected in the sixth inning for arguing balls and strikes, but the Orioles led, 3-2, entering the bottom of the ninth. With Murray behind the plate, Chicago’s Sherm Lollar drew a leadoff walk from Baltimore reliever Howie Fox. Next, Cass Michaels took a 3-2 pitch that looked like a strike, and Murray threw to second base in plenty of time to cut down pinch-runner Fred Marsh attempting to steal. The double play would have left the Orioles just one out from victory, but plate umpire Ed Hurley ruled that the pitch to Michaels was ball four, giving the White Sox two baserunners with nobody out instead.52 “First [Murray] fell forward on his knees on the plate, saying nothing,” described the Sun. “Then he sat on his haunches, crestfallen. Then he went through a series of gestures behind the plate to indicate to the ump where the strike zone is. At times the guy they call the ‘Deacon’ looked as if he were looking to the great beyond for support of his claim. Finaly [sic] he broke into wrathful full voice, walking up and down with the ump, shouting and stomping his feet.”53

“I just prayed loud enough for Hurley to hear, ‘Oh Lord, where does the pitch have to come to be a strike? This s.o.b. – same ol’ boy – is still blind,’” Murray recalled in 1983. “I was still down on my knees when Hurley gave me the thumb. Dykes came out and Hurley told him to get me out of there, quick. Jimmie said, ‘Sure, Ed, but not while the man is praying.’ That got Dykes a quick hook from Hurley, too.”54

Four batters later, the White Sox won the game, 4-3. Murray was suspended for three days and fined $100.55 An Orioles fan mailed a check to cover the penalty.56 Baltimore finished in seventh place with a 54-100 record. Murray appeared in only 22 games, batting .246. On December 1, he was sold to the New York Giants.

The Giants sent Murray to the Texas League in 1955 to play for their Dallas Eagles affiliate. Murray, 37, batted .329 with 25 homers and 80 RBIs in 110 games before a broken right thumb ended his season with just over five weeks still to play. He was named the league’s player of the year.57

In 1956, Murray spent most of the year on the disabled list, appearing in only 29 games for Dallas. He hit well for the Eagles in part-time duty in 1957 (.306, eight homers in 41 games) before July 24, when he was hired as the playing manager of the Giants’ Class A Eastern League farm club in Springfield, Massachusetts.58

Murray returned to the Texas League in 1958 and managed the Corpus Christi Giants to the league championship. He played in 93 games himself and batted .357 with 19 homers and 63 RBIs. In the All-Star Game, he dusted his armpits with the rosin bag. Murray made good contact (he struck out once every 10.9 at-bats in the majors), but when he did take a called third strike, “It was customary for him to pop to attention at the plate and hup-two-three his way to the bat rack in military fashion. At his destination, he’d present arms with his bat, place it in the rack, salute briskly and walk away.”59

In 1959, Corpus Christi finished 66-79, but Murray hit .328 with 38 RBIs in 198 at-bats and made four pitching appearances, too. The team moved to Rio Grande Valley in 1960. Murray went 0-for-2 in his final professional at-bats and earned unanimous manager of the year recognition after leading the Giants to a league-best 85-59 regular season record.60

In June 1961, there was speculation that the club would move again – 200 miles north to Victoria, Texas. “Ray Murray… is tremendously popular here,” noted the Victoria Advocate. “A number of folks here claim that with Murray as manager of Victoria – if Victoria is able to get the Valley team to move here – there would be an added 200-300 customers in the stands.”61 The club did relocate, and Victoria held a Ray Murray night at Riverside Stadium in August.62

The team belonged to Jimmie Humphries, who had previously owned the Oklahoma City franchise when Murray played there. “I’m a Jimmie Humphries man,” Murray said. “He’s a wonderful old gentleman, very kind and knows his baseball thoroughly.”63 But Humphries sold his club to El Paso-based investors that fall.64 The new management opted to retain George Genovese, a popular, fluent Spanish speaker who had managed the Giants’ Class D team there the previous year.65

Murray was hired that winter by the promotions department of the Dallas-Fort Worth Rangers, a Triple-A American Association team. By summertime, he was back in uniform as the third-base coach.66 Then, two days after manager Dick Littlefield was fired on July 16, Murray became the Rangers’ skipper.67 But Murray’s professional baseball career ended when the American Association dissolved at the end of the season.

After baseball, Murray spent 16 years as a deputy sheriff in Tarrant County, Texas.68 He was 85 when he died in Fort Worth on April 9, 2003 – less than six months after his wife, Jacque, predeceased him. The couple’s grave marker at Shannon Rose Hill Memorial Park in Fort Worth reads “Together Forever.”69

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and David Bilmes and fact-checked by Paul Proia.

Sources

In addition to sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted www.ancestry.com, www.baseball-reference.com, www.retorsheet.org and https://sabr.org/bioproject.

Notes

1 According to Baseball-Reference, Deacon Jones and Warren Newson are the only major-leaguers with the nickname “Deacon” who debuted after 1951. In addition to Ray Murray, the roster of Deacons that preceded them includes Deacon White, Deacon McGuire, Parson Nicholson, Will Smalley, George Darby, Sam Leever, Deacon Phillippe, Lucky Wright, Frank Morrissey, Deacon Van Buren, Bill McKechnie, Everett Scott, Carroll Jones, Deacon Meyers, Fred Johnson, Danny MacFayden, Wilcy Moore, Deacon Donahue, Vern Law and Alton Brown.

2 John Lyons, “Ray Murray to be Honored Friday Game with Ardmore,” Victoria (Texas) Advocate, August 1, 1961: 7.

3 Nine children are listed in the 1930 Census. The author was unable to access the 1940 Census, but the 1950 one includes Rebecca, who was born around 1935.

4 Ray Murray, American Baseball Bureau publicity questionnaire, January 4, 1946.

5 “Maplewood Wins, 3-2,” Raleigh (North Carolina) News and Observer, June 26, 1939: 9.

6 “Oak Level Gets Victory Over Littleton Outfit,” Rocky Mount (North Carolina) Telegram, August 29, 1939: 6.

7 Murray, American Baseball Bureau publicity questionnaire.

8 William W. Mowbray, The Eastern Shore Baseball League, (Centreville, Maryland: Tidewater Publishers, 1989): 60.

9 Mowbray, The Eastern Shore Baseball League: 185.

10 Harry Jones, “Ray Murray, Singing Catcher, ‘Can’t Think So Well’ When Silent,” The Sporting News, April 20, 1949: 19.

11 “10 Pocomoke Players Declared Free Agents,” Journal-Every Evening (Wilmington, Delaware), April 15, 1941: 24.

12 Murray, American Baseball Bureau publicity questionnaire.

13 “Baltimore Expected to Work with Athletics Next Season,” The Sporting News, September 18, 1941: 3.

14 C.M. Gibbs, “Tommy Thomas and First Contingent of Orioles Entrain,” Baltimore Sun, March 8, 1942: S3.

15 “Early Birds Impress Boss,” Baltimore Sun, March 12, 1942: 17.

16 C. M. Gibbs, “Orioles See Little Action,” Baltimore Sun, April 31, 1942: 15.

17 Gary Bedingfield, “Bob Neighbors,” https://www.baseballsgreatestsacrifice.com/biographies/neighbors_bob.html (last accessed September 11, 2022).

18 “Item: Fort Worth Army Air Fliers,” https://library.uta.edu/digitalgallery/img/20035862 (last accessed September 11, 2022).

19 Murray, American Baseball Bureau publicity questionnaire.

20 “Sports at a Glance,” Baltimore Sun, July 21, 1946: NM4.

21 John Lyons, “Houk Recalls the Day That Murray Buried Baseball,” Victoria Advocate, June 19, 1961: 9.

22 Jesse A. Linthicum, “Sunlight on Sports,” Baltimore Sun, December 6, 1946: 19.

23 C. Gibbs, “Gibberish,” Baltimore Sun, December 7, 1946: 11.

24 Joe Heiling, “Looking ’em Over,” Austin (Texas) American Statesman, August 17, 1960: A19.

25 Rich Marazzi and Len Fiorito, Baseball Players of the 1950s, (Jefferson, North Carolina: MacFarland & Company, 2014): 273.

26 John Cronley, “All Oklahoma City Happy Over Return of Ray Murray,” The Sporting News, May 26, 1948: 27.

27 United Press, “Indians Option Murray,” New York Herald Tribune, May 16, 1948: B3.

28 Jones, “Ray Murray, Singing Catcher, ‘Can’t Think So Well’ When Silent.”

29 John Cronley, “All Oklahoma City Happy Over Return of Ray Murray,” The Sporting News, May 26, 1948: 27.

30 Associated Press, “Chisox Chase Feller, 4-2; Bow to Tribe, 13-8,” Daily News (New York, New York), May 31, 1948: 41.

31 Associated Press, “Cleveland Recalls Murray,” New York Times, June 1, 1948: 33.

32 Associated Press, “Ray Murray Reinstated by Cleveland Indians,” Baltimore Sun, June 5, 1948: 11.

33 Associated Press, “Indians Release Catcher to Make Room for Paige,” Atlanta Constitution, July 8, 1948: 18.

34 “Ray Murray Bats 1.000 as Pilot,” The Sporting News, September 8, 1948: 28.

35 Jones, “Ray Murray, Singing Catcher, ‘Can’t Think So Well’ When Silent.”

36 Joe Heiling, “Looking ‘em Over,” Austin American Statesman, August 17, 1960: A19.

37 John Murray, “‘Deacon’ Murray, Who Favors Hillbilly Tunes, Intends to Say it with His Basehits, Too,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 17, 1953: 38.

38 Jones, “Ray Murray, Singing Catcher, ‘Can’t Think So Well’ When Silent.”

39 Jones, “Ray Murray, Singing Catcher, ‘Can’t Think So Well’ When Silent.”

40 Associated Press, “Ray Murray to Start for Tribe,” Salem (Ohio) News, April 20, 1950: 8.

41 “High-Riding Nats in Cleveland Tonite,” Daily Times (New Philadelphia, Ohio), May 24, 1950: 14.

42 Associated Press, “Tribe Thinks Brissie Will Make it Pennant Contenders,” Evening Independent (Massillon, Ohio), May 1, 1951: 10.

43 Murray, “‘Deacon’ Murray, Who Favors Hillbilly Tunes, Intends to Say it with His Basehits, Too.”

44 “A’s Lose Astroth, Yanks Renna in Saturday Game,” Bradford (Pennsylvania) Era, July 6, 1953: 4.

45 According to Baseball-Reference, while Murray was with Philadelphia, opposing baserunners were successful on just 39.8 percent (37 of 93) of stolen base attempts against him, and he was also credited with six pickoffs. During the same period, Retrosheet credits Murray with five pickoffs and records that would be base stealers succeeded against him 41.3 percent (38 of 92) percent of the time.

46 Among AL catchers with at least 35 starts, Murray’s 67% caught stealing percentage ranked second to Tipton (71%) in 1951 according to Baseball-Reference. In 1952, the top two were Clyde Kluttz (68%) and Murray (57%). In 1953, Astroth (72%) and Murray (60%).

47 As defined by Baseball-Reference, “FIP measures a pitcher’s effectiveness at preventing HR, BB, HBP and causing SO.”

48 Art Morrow, “Just Like Dream to Dykes – Kellner as Yankee-Killer,” The Sporting News, April 29, 1953: 14.

49 Rich Marazzi and Len Fiorito, Baseball Players of the 1950s, (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company, 2004): 273.

50 Lyons, “Houk Recalls the Day That Murray Buried Baseball.”

51 Lou Hatter, “Few Victories, But a Lot of Laughs,” Baltimore Sun, March 20, 1983: B10.

52 Ned Burks, “Fines,” Baltimore Sun, April 28, 1954: 23.

53 Ned Burks, “Orioles Lose. 3-2 and 4-3, to White Sox,” Baltimore Sun, April 26, 1954: 15.

54 Hatter, “Few Victories, But a Lot of Laughs.”

55 Burks, “Fines.”

56 H.T. “Yankees,” Daily News (New York, New York), May 5, 1954: 89.

57 Bill Rives, “Dallas, Eighth in ’54, Wins with Big Lift from Giants,” The Sporting News, September 14, 1955: 41.

58 Associated Press, “Ray Murray is Named Springfield Manager,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 25, 1957: D2.

59 Heiling, “Looking ‘em Over.”

60 United Press International, “Ray Murray TL Manager of the Year,” Brownsville (Texas) Herald, September 15, 1960: 15.

61 “Ray Murray Very Popular Here,” Victoria Advocate, June 4, 1961: 13.

62 John Lyons, “Ray Murray to be Honored Friday Game with Ardmore,” Victoria (Texas) Advocate, August 1, 1961: 7.

63 “Ray Murray Very Popular Here.”

64 Associated Press, “El Paso Votes to Buy Out Jim Humphries, Enter TL,” Daily Oklahoman, September 29, 1961: 39.

65 John Lyons, “Ray Murray Dismissed by Giants,” Victoria Advocate, October 19, 1961: 8.

66 John Lyons, “Ray Murray Named Coach of Rangers,” Victoria Advocate, July 3, 1962: 6.

67 Associated Press, “Murray New Ranger Coach,” Marshall (Texas) News Messenger, July 19, 1962: 43.

68 “Raymond Lee Murray,” https://www.legacy.com/us/obituaries/dfw/name/raymond-murray-obituary?id=16521326 (last accessed September 20, 2022).

69 “Raymond Lee ‘Ray’ Murray,” https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/7344311/raymond-lee-murray (last accessed October 24, 2022).

Full Name

Raymond Lee Murray

Born

October 12, 1917 at Spring Hope, NC (USA)

Died

April 9, 2003 at Fort Worth, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.