Whitey Herzog

In the annals of baseball dating back to when it first became a game played by professionals, the great teams have always taken on the persona of their managers. This includes the old Chicago White Stockings of the National League led by their first baseman-manager Adrian “Cap” Anson, and continues with managers such as Ned Hanlon of the Baltimore Orioles in the 1890s, and a couple of Hanlon’s protégés, John McGraw with the New York Giants and Hughie Jennings of the Detroit Tigers.1

In the annals of baseball dating back to when it first became a game played by professionals, the great teams have always taken on the persona of their managers. This includes the old Chicago White Stockings of the National League led by their first baseman-manager Adrian “Cap” Anson, and continues with managers such as Ned Hanlon of the Baltimore Orioles in the 1890s, and a couple of Hanlon’s protégés, John McGraw with the New York Giants and Hughie Jennings of the Detroit Tigers.1

Toward the middle of the twentieth century, there were Mel Ott with the New York Giants, Leo Durocher’s Dodgers and Giants, and Al Lopez’s “Go-Go” White Sox of the late ’50s.

Since free agency began, two managers have stamped their game on their teams and largely contributed to their success. They were Alfred Manuel “Billy” Martin, famous for Billyball, and Whitey Herzog, whose Whiteyball focused on speed, pitching, and defense.

Dorrel Norman Elvert Herzog was born on November 9, 1931, the second of three boys, to Edgar and Lietta Herzog in New Athens, Illinois, 40 miles east of St. Louis.2 Edgar worked at the Mound City Brewery and Lietta worked in a shoe factory.

To help make ends meet and make some extra money, young Dorrel, or “Relly” as he was called, dug graves, worked at the Mound City Brewery, delivered baked goods, and delivered newspapers.3

Young Herzog would sometimes skip school, hitchhike on Route 13 to Belleville, and then take a bus to Sportsman’s Park, home to the Browns and Cardinals. Herzog would not only watch his idols Stan Musial, Vern Stephens, and Enos Slaughter but would snatch up batting practice balls by sneaking into the ballpark early. He would bring the balls back to the New Athens sandlots, sell some and keep some to play with.4

At New Athens High School, Herzog, a left-handed thrower and batter, was a first baseman, pitcher, and outfielder. He also played guard on the basketball team.5 During his senior year, Herzog led the Yellow Jackets to the regional playoffs and had interest from colleges including the University of Illinois and St. Louis University. As a junior he batted .584, was named a second-team all-stater, and led the team to a spot in the championship game against Granite City. (New Athens lost, 4-1.) He was named second team all-state in baseball.

After graduating in 1949 Herzog bypassed college and signed a contract with the New York Yankees. Another Yankees recruit that year was Mickey Mantle.6 Herzog was recommended by scout Lou Maguolo and cross-checked by Tom Greenwade.7

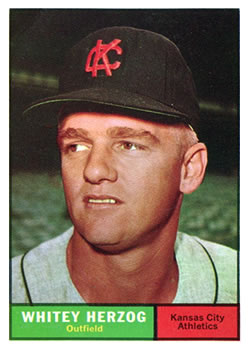

In his first year in the minors, playing for the Yankees’ Class-D Sooner State League team in McAlester, Oklahoma, Herzog hit .279; the following year he hit .351. While at McAlester he acquired the nickname Whitey, bestowed on him by a sportscaster in the McAlester because his light blond hair resembled that of a pitcher on the Yankees, Bob “White Rat” Kuzava.8

In 1951 Herzog hit a combined .276 for Class-C Joplin and Class-B Piedmont. The next season, 1952, after playing for Quincy in the Three-I League and Beaumont in the Double-A Texas League, he reached Triple A with Kansas City in the American Association. After the season, with the Korean War still raging, he was drafted into the US Army and spent two years in the Corps of Engineers.

The same year Herzog joined the Army, he married his high-school sweetheart, Mary Lou Sinn. As of 2018, they had been married 66 years and had three children, Debbie, Jim, and David.9

While stationed at Fort Leonard Wood in Waynesville, Missouri, Herzog got his first experience running a ballclub, when he managed the company baseball team.10

Discharged from the Army, Herzog played in 1955 for the Yankees’ Triple-A team in Denver. In 149 games he hit .289 with 21 home runs and 98 runs batted in.

After his success in 1955, Herzog hoped to spend the 1956 season with the Yankees. He made the majors, but with the Washington Senators. On April 2 Herzog was traded to the Senators in a seven-player deal that saw pitcher Mickey McDermott and shortstop Bobby Kline head to the Yankees.11

For the Senators in 1956, Herzog played in 117 games, all in the outfield except for five at first base. The 5-foot-11, 182-pound Herzog batted .245 with 4 home runs and 35 RBIs. In May of 1958 he was sold to the Kansas City Athletics. Before the 1961 season the Athletics traded him to the Baltimore Orioles, and after the 1962 season the Orioles traded him to the Detroit Tigers. Over the next six years, Herzog bounced back and forth between the majors and the minors and played with three other American League clubs, the Kanas City Athletics, the Detroit Tigers, and the Baltimore Orioles. He appeared in 634 career games, batting .257 with an on-base percentage of .354, and with 25 homers and 172 RBIs.

For the Senators in 1956, Herzog played in 117 games, all in the outfield except for five at first base. The 5-foot-11, 182-pound Herzog batted .245 with 4 home runs and 35 RBIs. In May of 1958 he was sold to the Kansas City Athletics. Before the 1961 season the Athletics traded him to the Baltimore Orioles, and after the 1962 season the Orioles traded him to the Detroit Tigers. Over the next six years, Herzog bounced back and forth between the majors and the minors and played with three other American League clubs, the Kanas City Athletics, the Detroit Tigers, and the Baltimore Orioles. He appeared in 634 career games, batting .257 with an on-base percentage of .354, and with 25 homers and 172 RBIs.

After batting only .151 in 52 games for the Tigers in 1963, Herzog retired as a player. Of his playing career, Herzog was known to say that baseball had been good to him once he stopped trying to play it.12

Herzog scouted for Kansas City in 1964 and was a coach in 1965 under Mel McGaha and Haywood Sullivan.13 In 1966 he Following the 1965 season, Herzog left the Athletics organization and was hired by the New York Mets organization. His first position in 1966 was third-base coach under Wes Westrum, on a team that went 66-95 and finished in ninth place ahead of only the Chicago Cubs. They finished 28 1/2 games behind the pennant-winning Los Angeles Dodgers.

The following year Herzog was named the Mets’ director of player development but also got his first taste of managing in professional baseball, when at 35 he guided the Florida Instructional League Mets for 50 games. Over the next six years, Herzog oversaw a number of players who played important roles in the pennant-winning Mets teams of 1969 and 1973, including Jerry Koosman, Gary Gentry, Jon Matlack; John Milner, and Wayne Garrett as well as players who had successful careers on other teams including Amos Otis, Nolan Ryan, and Ken Singleton. After seven years in the Mets organization Herzog, who disliked Mets Chairman M. Donald Grant, left the organization upset when the Mets passed him over for manager in 1972 after Gil Hodges died. (First-base coach Yogi Berra got the job.14)

Herzog quickly rebounded. On November 2, 1972, at the age of 40, he was named the manager of the Texas Rangers, replacing Ted Williams. Team owner Bob Short said general manager Joe Burke believed Herzog would help develop the team’s young talent.15

On April 7, 1973, Herzog made his managerial debut with the Rangers with a 3-1 loss to the White Sox. He did not get his first win until April 12, 4-0 over the Kansas City Royals.

The 1973 Rangers were a somewhat dysfunctional team. In the June amateur draft, the team drafted pitcher David Clyde number one overall ahead of future Hall of Famers Robin Yount and Dave Winfield. As part of the contract Clyde signed, he was to make two major-league starts before going to the minors. He pitched fairly well in the first couple of starts, but then batters began to get to him. Herzog was unable to get Bob Short to agree to send Clyde to the minors to get his footing. Herzog later said it was “a travesty.” Teammate Tom Grieve called it “the dumbest thing you could ever do to a high-school pitcher,” and said Short had effectively ruined Clyde’s career.16

At 138 games into the season with the Rangers sitting at 47-91, Herzog was fired and replaced by Billy Martin, who had recently been fired by the Detroit Tigers. Short knew Martin from his time as a Twins executive while Martin was manager. Short had allegedly once quipped to Herzog that he “would fire his grandmother for the chance to hire Billy.” A few days after his ouster, Herzog said, “I’m fired. I’m the grandmother.”17 Herzog was not the only member of the Texas Rangers staff to be fired late in the 1973 season; General Manager Joe Burke was also let go.

The following year, 1974, Herzog stayed in the American League West, becoming the California Angels’ third-base coach under manager Bobby Winkles. Herzog became the interim manager for four games after Winkles (30-44) was fired. After Dick Williams became the manager, Herzog stayed on as coach the rest of the year.

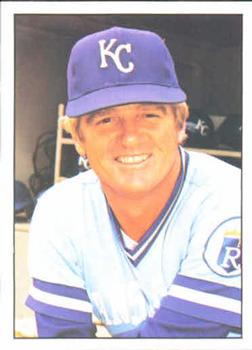

During the 1975 baseball season, Kansas City Royals GM Joe Burke was sensing that something was wrong despite the team being 50-46. He sensed a divide between team manager Jack McKeon and the team. On July 24, he fired McKeon and hired Herzog as manager on a deal worth $50,000 through the end of the 1976 season.18

Herzog inherited a solid Royals team with players like George Brett, John Mayberry, Paul Splittorff, Hal McRae, Frank White, Freddie Patek, Cookie Rojas, Doug Bird, Amos Otis, Dennis Leonard, and 39-year-old Harmon Killebrew. He managed the Royals to a second-place finish, seven games behind the Oakland Athletics.

Starting with his tenure with the Royals and continuing with the Cardinals, Herzog implemented a system of baseball well suited to the turf of both Royals Stadium and Busch Stadium and the antithesis of winning baseball via home runs. “Whiteyball” was predicated on great fielding, line-drive hitting, speed on the basepaths, and solid pitching.19

The 1976 season was a turning point in Herzog’s managerial career. “Whiteyball” worked especially well on Royals Stadium’s artificial turf.20 The team hit only 65 home runs, 11th in the American League, but George Brett and Hal McRae finished 1-2 in the AL batting race with batting averages of .333 and .332 respectively, and the team had eight players with 10 or more stolen bases, led by Freddie Patek (51 SB’s). On the pitching side, the Royals had four pitchers with 10 or more wins and Mark Littell and Steve Mingori each had 10 or more saves.

The 1976 season was a turning point in Herzog’s managerial career. “Whiteyball” worked especially well on Royals Stadium’s artificial turf.20 The team hit only 65 home runs, 11th in the American League, but George Brett and Hal McRae finished 1-2 in the AL batting race with batting averages of .333 and .332 respectively, and the team had eight players with 10 or more stolen bases, led by Freddie Patek (51 SB’s). On the pitching side, the Royals had four pitchers with 10 or more wins and Mark Littell and Steve Mingori each had 10 or more saves.

This team led the Royals to their first AL West title with a record of 90-72, edging out Oakland by 2½ games. The 1976 American League Championship Series pitted the Royals against the Yankees, with the teams splitting the first four games. In the pivotal Game Five at Yankee Stadium, with the Royals down by three in the eighth inning, George Brett hit a game-tying three-run home run off Grant Jackson. But in the bottom of the ninth inning, Yankees first baseman Chris Chambliss hit a home run off Littell to win the pennant.

The next year, 1977, the Royals were paced by a career year by Al Cowens, who batted .312 with 23 home runs and 112 runs batted in. Combined with strong pitching that included 20-game winner Dennis Leonard, the team won 102 games and finished eight games ahead of the Texas Rangers. The ALCS was a rematch against the Yankees. The Royals took a two-games-to-one lead and seemed poised to advance to the World Series when an issue arose with first baseman John Mayberry, who after dropping a foul ball, was pulled by Herzog and never played for the Royals again. After the Royals lost Game Four, 6-4, Herzog refused to play Mayberry in Game Five, despite the pleas from his teammates, and the Royals lost, blowing a 3-2 ninth-inning lead.

In 1978 the Royals won 90-plus games for the fourth year in a row and finished 92-70, five games ahead of the Rangers and Angels. In their third consecutive matchup with the Yankees, the Royals lost again, in four games.

The 1979 Royals finished with 85 wins, good enough for second place, three games behind the California Angels. This step back cost Herzog his job. The firing had less to do with on-field performance than the fact that there had been friction between Herzog and Royals owner Ewing Kauffman. Herzog got a $50,000 bonus each year if the Royals drew 2 million fans, which they did in 1978-1979, but Herzog felt that Kauffman and the front office did not really want to improve the team through free agency. (The next season, under Jim Frey, the Royals won the AL West with a record of 97-65, swept the Yankees in the ALCS, and lost to the Philadelphia Phillies in six games in the World Series.)

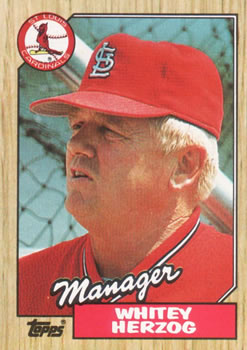

In June of 1980 Herzog moved east on I-70 to take over the beleaguered St. Louis Cardinals from Ken Boyer, with the team’s record at 18-33 and having gone 5-22 over the previous 27 games.21 Under Herzog the Cardinals were 38-35. On August 17, he was promoted to take over for John Claiborne as the Cardinals GM; his successor as manager was Red Schoendienst.

After the season Herzog acquired Bruce Sutter and Darrell Porter, who had played for him for three years in Kansas City. He also demoted Red Schoendienst to coach and took over the dual role of general manager and manager, the first person to serve in both roles since Connie Mack was GM and manager (and owner) of the Philadelphia Athletics in 1950.22

The 1981 season was interrupted by a 50-day players strike. When the games resumed in August, the season was split into two halves, with each half’s winner advancing to the playoffs. This ended up hurting the Cardinals, who had the best overall record in the NL East, 59-43, but finished second in both halves, to Philadelphia and to Montreal.

The 1981 offseason saw the acquisitions of Lonnie Smith, Steve Mura, Willie McGee, and Ozzie Smith, as well as the re-signing of Joaquin Andujar. These acquisitions along with the players already in place led the 1982 Cardinals to a 92-70 season, edging out the Phillies by three games. They swept the Atlanta Braves in the National League Championship Series. Three games into the season, Herzog gave up his position as GM to focus on managing. He was replaced by Cardinals assistant GM Joe McDonald, three games into the 1982 season.23 On April 10, 1982, the stress of being general manager and manager was beginning to take away from Herzog’s abilities on the field so he turned over the general manager duties to McDonald, who had been hired by the Cardinals in 1981 as an executive assistant and assistant GM. McDonald had not only worked with Herzog when they were both with the New York Mets, but McDonald had previous GM experience with the Mets as he had been their GM from 1975-1980.

The 1982 World Series presented a stark contrast between the Cardinals and the Milwaukee Brewers, known as Harvey’s Wallbangers after manager Harvey Kuenn. Milwaukee led the AL with 216 home runs. The Cardinals hit only 67 homers, last in the NL, but their team batting average was .264, tied for second, and the led the league with 200 stolen bases. The Series went the full seven games, with the Cardinals coming back after going down three games to two, to win Game Six, 13-1 and Game Seven, 6-3, giving the Cardinals their first World Series championship in 18 years, and Herzog his first.

The Cardinals were unable to repeat and finished the 1983 season 79-83, fourth in the NL East. The major event of the season came at the June 15 trade deadline, when the Cardinals shocked the baseball world by trading former MVP and reigning Gold Glove winner Keith Hernandez to the New York Mets for Rick Ownbey and Neil Allen. Herzog said he made the move because the Cardinals needed more pitching, and that the plan was to bring Andy Van Slyke up from Triple A and move George Hendrick to first base.24 It was later discovered that the trade was due to the longtime personality conflict between Hernandez and Herzog.25 There were rumors of Hernandez’s cocaine use, which turned out to be true. This also affected Joaquin Andujar and Lonnie Smith, leading to the trade.26

After finishing in third place (84-78) in 1984, the Cardinals went to the World Series in both 1985 and 1987.

In the 1984-85 offseason George Hendrick was part of a four-player trade for John Tudor and first baseman Jack Clark was acquired from San Francisco. This trade was done to stabilize the first-base position for the Cardinals. Also, 1985 saw the emergence of left fielder Vince Coleman, who stole a rookie-record 110 bases en route to Rookie of the Year honors and also led to the trade of Lonnie Smith to Kansas City.

The 1985 season in the National League East came down to a battle the last couple of weeks of the season between the Cardinals and the New York Mets. The Cardinals ended up with a record of 101-61, edging out the Mets by three games. They were led by Jack Clark’s 22 home runs, and also stole 314 bases; besides Coleman’s 110 steals, Willie McGee contributed 56 and Tommy Herr and Ozzie Smith each had 31. Pitchers John Tudor and Joaquin Andujar each won 21 games and Jeff Lahti, Ken Dayley, and Todd Worrell combined to save 35 games, to make up for the loss of Bruce Sutter who had signed in the offseason with the Braves.

In the NLCS, against the Dodgers, with the series tied at two games apiece, and the score 1-1 in the bottom of the ninth, Ozzie Smith hit a solo home run off LA’s Tom Niedenfuer to win the game, 2-1. The call from Jack Buck — “Go crazy, folks, go crazy, it’s a home run” — was ranked by mlb.nbcsports.com as number 21 of the 32 best calls in sports history.27 Two days later, in Dodger Stadium, Jack Clark hit a three-run home run in the ninth inning off Niedenfuer to capture the pennant for the Cardinals. The win came at a cost: Before Game Four, Vince Coleman’s leg was fractured in a freak accident with the tarp at Busch Stadium.28

With both teams from Missouri, the 1985 World Series was known as the I-70 Showdown Series and the Show-Me World Series, The Cardinals faced Herzog’s former team, the Royals. Many of the Royals’ leaders that year were holdovers from the Herzog era. The Royals had won 10 fewer games than the Cardinals, and St. Louis was the heavy favorite.

The Cardinals won the first two games, 3-1 and 4-2, and Kansas City took Game Three, 6-1. After John Tudor shut out Kansas City, 3-0, the Royals staved off elimination by winning Game Five, 6-1. Game Six was one of the most memorable games in World Series history. The game was scoreless through seven innings. In the bottom of the ninth, with St. Louis leading 1-0, Herzog called on rookie closer Tim Worrell to give the Cardinals their second championship in four years. The leadoff batter, pinch-hitter Jorge Orta, hit a bouncer to Jack Clark, who threw to Worrell covering first base. Orta was called safe on the play by umpire Don Denkinger.29 Replays showed that Orta was out by half a step, but in the days before instant replay, Denkinger chose not to overrule himself and the call stood. The Cardinals proceeded to self-destruct. Steve Balboni hit a popup in foul territory that neither Darrell Porter nor Jack Clark could come up with; he subsequently singled. After Jim Sundberg’s bunt forced Orta at third, a passed ball moved the runners up to second and third. Hal McRae was then intentionally walked. Pinch-hitter Dane Iorg singled to right and the tying and winning runs scored, to force a seventh game. After the drama of Game Six, Game Seven was anticlimactic as the Royals’ Bret Saberhagen shut out the Cardinals, 11-0, to win the World Series. The only drama in Game Seven was that Herzog became the first manager since Billy Martin (in 1976) to be ejected from a World Series game.

The next season the Cardinals slumped to a record of 79-82, 28½ games behind the first-place New York Mets, the only positives being that both Ozzie Smith and Willie McGee captured Gold Gloves and pitcher Todd Worrell earned Rookie of the Year Honors.

During the 1986-1987 offseason, the Cardinals, in an effort to improve their catching, traded catcher Mike LaValliere and outfielder Andy Van Slyke to the Pirates for four-time All-Star Tony Peña. This trade along with the 35 home runs from Jack Clark, the 109 stolen bases of Vince Coleman, and a pitching staff that had four winners of 10 or more games, helped the Cardinals improve by 16 wins and narrowly overtake the Mets and Expos. In the NLCS the Cardinals came from a three-wins-to-two deficit to defeat the San Francisco Giants in seven games and advance to their third World Series in six years.

During the 1986-1987 offseason, the Cardinals, in an effort to improve their catching, traded catcher Mike LaValliere and outfielder Andy Van Slyke to the Pirates for four-time All-Star Tony Peña. This trade along with the 35 home runs from Jack Clark, the 109 stolen bases of Vince Coleman, and a pitching staff that had four winners of 10 or more games, helped the Cardinals improve by 16 wins and narrowly overtake the Mets and Expos. In the NLCS the Cardinals came from a three-wins-to-two deficit to defeat the San Francisco Giants in seven games and advance to their third World Series in six years.

Herzog’s Cardinals faced the Minnesota Twins in a World Series played entirely on artificial turf (as had occurred in 1985). The Twins came back from a three-games-to-two deficit and won Game Six, 11-5, and Game Seven, 4-2.

Over the next couple of years the Cardinals slumped. In 1988 they finished with a record of 76-86 in fifth, ahead of only the Philadelphia Phillies, and 25 games behind the East-leading New York Mets. In 1989 they improved by 10 games to finish 86-76, but finished seven games behind the Chicago Cubs.

The 1990 season proved very difficult for Herzog and the Cardinals, and culminated in his resignation when the Cardinals, with a 33-47 record, were in last place in the National League East.30

The end of Herzog’s Cardinals tenure also ended his managerial career, with a record of 1,281-1,125, a .532 winning percentage. He had a postseason record of 26-25, with the one World Series championship in 1982, three AL West titles, three NL East titles, and three National League pennants.31

Herzog’s departure from the Cardinals did not end his career in baseball. In 1992, after holding various positions with the California Angels, he was named general manager. Over the next two years, the Angels fell short of expectations, finishing 72-90 in 1992 and 71-91 in 1993. In January 1994 he resigned, citing the opportunity to do other things.32 He had spent 45 years as a player, coach, manager, and general manager.

As recently as 2018, Keith Hernandez, despite having been traded by Herzog, had nothing but the highest praise for Herzog’s managerial and overall baseball acumen. “He was a great manager, best I ever played for,” Hernandez said. 33

Herzog was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 2010. On a more local note, the baseball field at New Athens High School was renamed Whitey Herzog Field in honor of Herzog, who donated money to have the field renovated.

Herzog took the talent of his teams and where they played, to their full capacities. He took two teams from smaller markets to great heights.

Herzog died at the age of 92 on April 15, 2024.

Notes

1 On Anson, see David Fleitz; Cap Anson: sabr.org/bioproj/person/9b42f875; on Hanlon, see “The ‘Inside’ Scoop on Inside Baseball: Plus ‘Inside Joke,’ ‘Inside Job,’ and other ‘inside, words. merriam-webster.com/words-at-play/the-inside-scoop-on-inside-baseball. Retrieved July 1, 2018.

2 Dan O’Neil, “Whitey Herzog: The Pride of New Athens,” USA Today, July 18, 2010. stltoday.com/sports/baseball/professional/whitey-herzog-the-pride-of-new-athens/article_88fad913-7b40-5683-88f9-417f30044412.html; Retrieved July 15, 2018.

3 O’Neil, “Whitey Herzog: The Pride of New Athens.”

4 O’Neil, “Whitey Herzog: The Pride of New Athens.”

5 O’Neil, “Whitey Herzog: The Pride of New Athens.”

6 O’Neil, “Whitey Herzog: The Pride of New Athens.”

7 Scouting information thanks to Rod Nelson, chair of SABR’s Scouts Committee.

8 Nelson, SABR Scouts Committee.

9 Transcript of Whitey Herzog’s Hall of Fame Speech. stltoday.com/sports/baseball/professional/transcript-of-whitey-herzog-s-hall-of-fame-speech/article_fec87545-dd96-52e2-9038-f2aa37d9ff5d.html; July 26, 2010; retrieved July 15, 2018.

10 ’O’Neil, “Whitey Herzog: The Pride of New Athens.”

11 baseball-almanac.com/players/trades.php?p=herzowh01; retrieved July 15, 2018.

12 Glenn Liebman, “Here Are Some New Names for Humor Hall of Fame,” Baseball Digest, March 1992: 23.

13 John E. Peterson, The Kansas City Athletics: A Baseball History, 1954 — 1967 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2003), 308.

14 Richard Sandomir, “Leaving Mets Put Herzog on a Path to the Hall,” New York Times, July 23, 2010. nytimes.com/2010/07/24/sports/baseball/24herzog.html?ref=sports. Retrieved August 8, 2018.

15 “Texas Rangers Name Herzog Manager,” New York Times, November 3, 1972. nytimes.com/1972/11/03/archives/texas-rangers-name-herzog-manager.html. Retrieved August 8, 2018. See also Paul Rogers, The Impossible Takes a Little Longer (Dallas: Taylor Publishing Company, 1990).

16 Brad Townsend, “40 Years After Memorable Debut, Ex-Ranger David Clyde Reflects on Career Cut Short,” Dallas Sports Day News; June 22, 2013; sportsday.dallasnews.com/texas-rangers/rangersheadlines/2013/06/22/townsend-40-years-after-memorable-debut-ex-ranger-david-clyde-reflects-on-a-career-cut-short; retrieved August 8, 2018. The contract also included a $125,000 signing bonus.

17 Jimmy Keenan and Frank Russo, “Billy Martin,” SABR BioProject, sabr.org/bioproj/person/59c5010b.

18 United Press International, “Royals, Fire McKeon, Hire Angels’ Herzog,” Milwaukee Sentinel. July 25, 1975.

19 Whitey Herzog and Kevin Horrigan, White Rat — A Life in Baseball. (New York: Harper and Row, 1987), 145.

20 Herzog and Horrigan.

21 William Nack, “They’ve Committed Cardinal Sins. Bad Fortune and Worse Playing Have Put Hard-Hitting St. Louis in Last Place — And Beleaguered Ken Boyer Out of a Job,” Sports Illustrated, June 16, 1980.

22 Cardinals Clinch Eastern Title,” New York Times, September 28, 1982. https://nytimes.com/1982/09/28/sports/cardinals-clinch-eastern-title.html.

23 baseball-reference.com/teams/STL/1982-schedule-scores.shtml; retrieved December 9, 2018.

24 Kevin Paul Dupont, “Keith Hernandez Sent to Mets for Allen, Ownbey,” New York Times, June 15, 1983: 46.

25 Jeff Pearlman, The Bad Guys Won (New York: ITBooks, 2011), 32.

26 Harold Friend, “Keith Hernandez Used Cocaine and Was Forced to Name Others,” Bleacher Report, February 17, 2012. bleacherreport.com/articles/1070283-keith-hernandez-used-cocaine-and-was-forced-to-name-others; Retrieved August 10, 2018.

27 Joe Posnanski, “The 32 Best Calls in Sports History (and a Scully vs. Buck Debate,” mlb.nbcsports.com/2013/10/16/the-32-best-calls-in-sports-history-and-a-scully-vs-buck-debate/; retrieved August 10, 2018.

28 Benjamin Hochman, “The Day the Tarp Ate Vince Coleman,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 12, 2015.

29 mlb.com/video/denkingers-missed-call/c-13062921; Retrieved August 11, 2018.

30 Associated Press, “An ‘Embarrassed’ Herzog Quits as Cardinals’ Manager,” New York Times, July 7, 1990. nytimes.com/1990/07/07/sports/an-embarrassed-herzog-quits-as-cardinals-manager.html. Retrieved August 26, 2018.

31 baseball-reference.com/managers/herzowh01.shtml. Retrieved August 26, 2018.

32 Bob Nightengale, “Angels GM Herzog Out in Surprise Resignation,” Los Angeles Times, January 12, 1994.

33 David Jordan, “Keith Hernandez on his Cardinals Career, the Modern Game and a Mets Trade That Never was,” The Sporting News, May 23, 2018.

Full Name

Dorrel Norman Elvert Herzog

Born

November 9, 1931 at New Athens, IL (USA)

Died

April 15, 2024 at St. Louis, MO (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.