Mel McGaha

Mel McGaha’s life was part Frank Merriwell, part Greek tragedy.

Mel McGaha’s life was part Frank Merriwell, part Greek tragedy.

Like Merriwell, the fictional athlete popularized in dime novels, McGaha (pronounced mŭ-GAY-hay) was a clean-cut, handsome figure who excelled in multiple sports as a collegian. A University of Arkansas graduate, he was a basketballer drafted by the New York Knickerbockers, a two-way football player signed by the Los Angeles Rams, and a catcher engaged by the St. Louis Cardinals.

A deadly bus accident in McGaha’s first year in the minors left him with the first of two serious injuries that kept him from playing in the major leagues. Guiding three minor-league teams to pennants earned McGaha a job as the skipper of the 1962 Cleveland Indians at age 35, but pitching staff mismanagement and authoritarian rule proved his downfall. Piloting the Kansas City Athletics three years later, McGaha couldn’t win enough for owner Charlie Finley, hamstrung by a roster filled with talented but green bonus babies.

Fred Melvin McGaha was born on September 26, 1926, in Bastrop, Louisiana, the only child born to Cajuns Fred Holmes McGaha and his wife, Ethie.1 In 1930, the McGahas lived in North Little Rock, Arkansas, with Mel’s father employed as a workshop laborer. The 1940 U.S. Census shows the family living in Pulaski County, with the senior McGaha working in a railroad shop.

Young McGaha played basketball at Mabelvale (Arkansas) High School, with their home games held outdoors in Mel’s senior year after their gymnasium burned down.2 McGaha also played baseball for a local YMCA and several industrial teams.3

In the fall of 1943, 16-year-old McGaha entered the University of Arkansas on a basketball scholarship.4 On the cusp of the team’s first-round appearance in the 1944 NCAA post-season tournament, two of McGaha’s teammates were permanently crippled, and a school instructor was killed, when they were struck by a car while changing a flat tire at midnight during a rainstorm. Arkansas withdrew from the tournament, and its replacement, the University of Utah, won the national championship.5

Arkansas reached the NCAA Western Regional finals the next year, but without McGaha. Like many other Razorback athletes, he’d been drafted.6 McGaha served in the Army Air Corps for nine months, discharged early thanks to the end of World War II.7 In December 1945, McGaha married Christina Elizabeth Lansford, a former University of Arkansas homecoming queen.8

Back on the hardwood in early 1946, McGaha earned honors for his play at New York’s Madison Square Garden, highlighted in a Look magazine article showcasing the wonders of stop-action color photography.9 A year later, he skipped a return engagement at the Garden to play football in the 1947 Cotton Bowl.10 Through snow, sleet and freezing rain, Arkansas fought the LSU Tigers, and quarterback Y.A. Tittle, to a scoreless tie.

Though he didn’t play football in high school, McGaha had joined the Razorbacks football team as a freshman, attracted by higher-paying scholarships for footballers.11 A 165-pound defensive end at first, by his sophomore season, McGaha had put on 30 pounds and was drawing attention as an offensive receiver and punt-blocker.12

Three weeks after the Cotton Bowl, McGaha suffered a dislocated right elbow playing basketball.13 Back on the court after a two-month recovery, he couldn’t shoot from beyond 15 feet.14 Told by a doctor he’d never be able to throw right-handed again, McGaha, who was playing semi-pro baseball and dreamed of a big-league career,15 began teaching himself to throw left-handed. His right arm healed well enough to abandon the conversion but was never the same.16

In McGaha’s final year at Arkansas he celebrated the birth of a daughter, Patricia. 17 (The McGahas’ second child, a boy, Fred Royce, was born in 1950.) On the gridiron, McGaha returned an intercepted pass 70 yards for a game-tying touchdown in the inaugural Dixie Bowl on New Year’s Day 1948 in Birmingham, Alabama. His weaving, stumbling run was the longest bowl game interception by an Arkansas player, a record that still stood 75 years later.18

After graduating, McGaha signed a contract with the St. Louis Cardinals.19 He had played first base for Arkansas a year earlier, on the university’s first varsity team in 20 years, then blossomed into an offensive star after moving behind the plate in the spring of 1948.20 McGaha’s baseball-playing earned him letters in three sports, a feat unmatched at Arkansas until future NFL Hall of Famer Lance Alworth did it in 1960.21

Assigned to the Houston Buffaloes of the Double-A Texas League, McGaha played just two games before being shipped to the Class-C Northern League Duluth Dukes. 22 On July 25, 1948, the Dukes were traveling from a game in Wisconsin when their bus flipped over and caught fire after it was hit head-on by a truck carrying dry ice. Four of McGaha’s teammates died, along with manager George Treadwell, who was driving the bus. McGaha had been sitting behind Treadwell until he was bumped to the back of the bus by another player who was the alternate driver. That player was among those who perished.23

McGaha’s right shoulder was badly separated in the crash, with his collar bone turned completely around. Once able to play again, McGaha, who’d hit .353 in 134 plate appearances before the accident, asked to leave Duluth.24 He finished the season playing outfield for Winston-Salem of the Class-C Carolina League, hitting .390 there, with a slugging percentage near .500.

After the baseball season, the Los Angeles Rams of the National Football League signed McGaha to play alongside future Hall of Fame receiver Tom Fears. McGaha never reported though, seeing irreconcilable schedule conflicts with his preferred sport, baseball.25

Less conflicted about basketball, McGaha next joined the New York Knickerbockers of the Basketball Association of America, an NBA pre-cursor. The 31st pick in the BAA 1948 draft, McGaha soon became one of the league’s top rookies.26 His toughness impressed Knicks head coach Joe Lapchick, who had McGaha guard opponents’ top scoring guards. “As a hatchet man I usually would go in and rough a fellow up a bit as he shot,” recalled McGaha.27 With little playmaking ability and unable to shoot effectively from long range, McGaha’s contributions were largely on defense. Over 51 games, he averaged 3.5 points and one assist.28

McGaha spent the 1949 baseball season with the Triple-A Columbus Red Birds of the American Association, where he hit .290 in 114 games. The Columbus Evening Dispatch admired how McGaha “prevented experienced pitchers from making a greenhorn out of him by refusing to take a full cut at the ball,”29 but that approach produced few extra base hits. Still, McGaha was considered a star-to-be by Cardinals owner Fred Saigh.30

Feeling professional basketball left him too exhausted for baseball season, McGaha traded in his satin shorts for a clipboard during the 1949-1950 hoops season, coaching Fayetteville’s West Fork High School boys basketball team to a county title.31 Over the next few years, McGaha continued to coach and referee high school basketball.32

McGaha returned to Columbus for the 1950 season, but in June was sent back to Houston. He hit .269 with little power, but did club a three-run game-winning 10th inning home run off former Detroit Tiger ace Schoolboy Rowe in early September.33

April 1951 was a roller coaster for McGaha, back with the Buffaloes. He went 3-for-4 in a pre-season tilt against the world champion New York Yankees, then separated his left shoulder diving in a regular season game.34 Expected to be out for the season, McGaha came back six weeks after surgery. He hit only .224 in 143 at-bats but earned a $238.10 bonus after Houston won the pennant.

McGaha tried catching once again in 1952. Described by one sportswriter as, “Tall as the pines in his native Ozarks and just as green behind the plate,”35 he began the year as Houston’s starting backstop, but by Memorial Day was in the outfield. McGaha played a career-high 132 games, including two in which he scored game-winning runs on hits by part-time infielder Earl Weaver.36

In December 1952, Houston sent McGaha and $30,000 to the unaffiliated Shreveport (Louisiana) Sports of the Texas League, for outfielder Harry Elliott.37 At the time, McGaha called it the best break he ever had in baseball. When player/manager Mickey Livingston went down with appendicitis the following May, “whip-smart” McGaha was named interim manager.38 He led the team to several victories, earning accolades for how well he ran the team. A .300 hitter through mid-June, McGaha tailed off to finish the year hitting .261 but collected a career-high 97 hits and 66 RBIs, playing mostly first base.39

After the 1953 season, McGaha considered quitting baseball. He realized he’d never play in the majors and saw coaching basketball and/or football as his future.40 The previous off-season, McGaha had coached the freshman basketball team at Arkansas and in September became head coach for Arkansas A&M’s basketball squad.41 He’d also become chief scout and end coach for A&M’s football team.42 Thoughts of quitting ended when Sports owner Bonneau Peters released Livingston in December over a conflict-of-interest and persuaded McGaha to replace him.43

The youngest skipper in the high minors, McGaha steered the Sports to a 9-0 start on their way to the 1954 Texas League regular season crown, Shreveport’s first ever. 44 Playing right field, he went 3-for-4 with a two-run homer in the clincher. Even though the Sports lost to the Fort Worth Cats in the first round of the TL playoffs, one Shreveport Times sportswriter still gushed that “no manager ever wound up a season more thoroughly liked and respected by his whole squad.”45

The following year, Shreveport finished third in the regular season, but won the TL playoffs, closing out San Antonio in the first round on a no-hitter by Billy Muffett, then coming back from a 3-1 deficit to win the finals over Houston in seven games.46 In the annual battle between Texas League and Southern Association champions known as the Dixie Series, Shreveport was swept by the Mobile (Alabama) Bears.

During the 1955-1956 hoops season, McGaha coached the Arkansas A&M Boll Weevils to a second-place finish in their conference after guiding them to their first .500 season ever the year before. McGaha resigned after two seasons with A&M hoping to complete his master’s degree, but he never did.47

In early 1956, McGaha relocated his family to Shreveport from Arkansas and took over leadership of the Sports’ annual free baseball clinic, which offered participants the prospect of a contract with the club. For nearly two decades, McGaha led what later became a city-run clinic, bringing in major league coaches and players once he reached the big leagues.48

McGaha spent two more years as Shreveport’s player/manager but could not recreate the magic of his first two. The team’s feature attraction in 1956 was Ken Guettler, who clubbed a Texas League-record 62 home runs.49 McGaha hit .326, with 10 home runs, five of them while pinch-hitting.50 He also played every position except third base and catcher.51

The longest tenured manager in the Texas League in 1957,52 McGaha piloted a team that included Joe DiMaggio’s pitcher cousin Bart, but not a single 20-home run hitter. The Sports finished dead last.

After the season, owner Peters, whose all-white Sports were drawing few fans and being boycotted by African-Americans in Shreveport,53 announced plans to sell the club. Encouraged to look for a new job, McGaha immediately caught on with the Cleveland Indians’ Double-A affiliate in Mobile, which made him their player/manager.54 Before leaving for Alabama, McGaha spent a few weeks catching for the Havana Reds in the Cuban Winter League.55

The Bears finished the 1958 regular season in second place, with McGaha pitching a complete game in a victorious season finale.56 A pinch-hit appearance in the Bears’ Southern Association playoff loss to Birmingham proved to be his swan song.57 McGaha finished his playing career with a .277 batting average, 45 home runs and only 166 strikeouts in nearly 2,600 at-bats.

In 1959, bleacher renovations to Hartwell Field, the Bears’ home ballpark,,58 forced the team to take a 28-game season-opening road trip. They went 17-11, impressing fans and the press alike. After winning 14 straight in August, Mobile took the Association’s second half title, led by league MVP and Triple Crown winner Gordy Coleman,59 and bested first-half champion Birmingham in a rancorous playoff.60

McGaha’s success caught the eye of budding sports mogul Jack Kent Cooke, who hired McGaha to manage his Toronto Maple Leafs, a Cleveland Indians Triple-A affiliate. Cellar-dwellers the year before, Toronto dominated the International League in 1960, going 100-54 behind ace Al Cicotte, slugger Jim King and infielder Sparky Anderson.61 McGaha was selected IL Manager of the Year and The Sporting News Minor League Manager of the Year.62

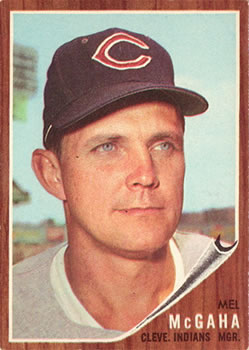

McGaha, now a hot commodity,63 was bumped up to the Indians coaching staff in 1961, where he handled first base chores for manager Jimmy Dykes. The day after the Indians finished the season with their worst record in 15 years (78-83), GM Gabe Paul fired Dykes, the major league’s oldest skipper, and replaced him with the youngest, 35-year-old McGaha.64

McGaha, now a hot commodity,63 was bumped up to the Indians coaching staff in 1961, where he handled first base chores for manager Jimmy Dykes. The day after the Indians finished the season with their worst record in 15 years (78-83), GM Gabe Paul fired Dykes, the major league’s oldest skipper, and replaced him with the youngest, 35-year-old McGaha.64

“I have one philosophy in baseball,” McGaha said after his selection. “That is to win. I play to win and I’ll do anything to achieve that purpose. I know that sounds brutal, but there it is.”65 The Cleveland Plain Dealer called McGaha a straight-shooter “who wears a velvet glove over an iron fist.”66 On his way out, Dykes, predicted McGaha would struggle “because there are too many lawyers on the club.”67 He didn’t name names but by the end of spring training, Cleveland traded away veterans Jim Piersall, Johnny Temple, and Vic Power, each of whom the press considered clubhouse troublemakers.68

With few accomplished regulars and his ace, Jim “Mudcat” Grant, limited to pitching on weekends due to Army obligations, McGaha began the season with platoons at every outfield position and a fluid rotation. On April 22, a doubleheader sweep of the Yankees put Cleveland in first place, and snapped a string of 19 consecutive losses at Yankee Stadium. By Memorial Day, pitcher Dick Donovan, acquired from the Washington Senators for Piersall, was 8-0, and the Indians had set a major league record with 28 home runs in a nine-game span.69 McGaha was flaunting convention, like putting the winning run on base to get a more favorable matchup, and coming away victorious.70 The Baltimore Sun called the college educated McGaha well-mannered and “a shining example of the new type of field leader baseball is turning to these days.”71

Cleveland jumped two games ahead of the Yankees with another doubleheader sweep, on June 17 at home, in front of over 70,000 fans, the AL’s largest crowd of the season.72 The wheels fell off starting in mid-July, though, as first-place Cleveland lost nine straight and 32 of 44 to fall into eighth place.73

The Indians’ decline was widely pinned on McGaha’s handling of his pitching staff. The press decried his habit of yo-yoing pitchers between starting and relief, like former 18-game winner Jim Perry and 19-year-old fireballer Sam McDowell. Quick to pull a struggling pitcher, McGaha leaned heavily on his bullpen, prompting Indians beat writer Bob Dolgan to observe that McGaha “plays each game as though it meant the pennant, using pitchers as though there were no tomorrow.”74 One Philadelphia sportswriter wise-cracked “McGaha was a candidate for manager of the century through last June and a candidate for obscurity by August.”75

Word also got out that McGaha had become unpopular in the clubhouse. He had banned beer and card games there and imposed a strict curfew on the road, enforced by bed checks.76 In the face of unrelentingly negative press reports, McGaha willed the Indians to a 17-13 record over the next five weeks, but it was too little, too late. Before a home doubleheader on the next-to-last day of the season, Paul informed McGaha his contract wouldn’t be renewed. Given permission to pursue another opportunity, he left after the day’s games without saying a word to his players.77

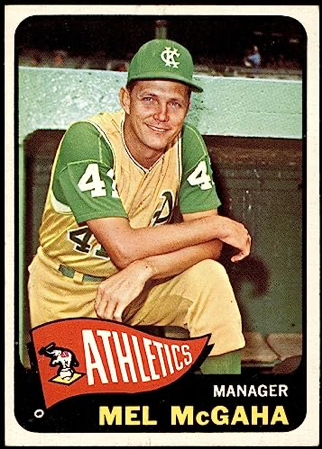

McGaha’s other opportunity was a job with Charlie Finley’s Kansas City Athletics as a front office executive and on-field coach.78 After a five-state, 10-city pre-season tour to drum up ticket sales, McGaha donned an A’s new green and gold uniform to coach first base, and occasionally third, for manager Eddie Lopat.79

McGaha began the 1964 season as one of six A’s coaches, an unusually large staff at that time,80 but in early-June was assigned to manage the A’s Wytheville, Virginia, rookie club in the Appalachian League. Before he’d finished packing, McGaha was tabbed to take over the last-place A’s; Finley’s fourth manager in four years. “I’ve found out that in this business you don’t outsmart too many people,” McGaha said upon his appointment, “but you can outwork them and that’s what I’m going to try to do.”81

A former pupil, the Indians’ McDowell, beat the A’s in McGaha’s Kansas City managerial debut, hurling his second career shutout. The A’s won eight of their next nine games to escape the basement, but then went 9-21. On July 23, rookie shortstop Bert “Campy” Campaneris made McGaha smile, as he debuted with a pair of home runs to key an A’s victory. In September, another talented rookie, 19-year-old John “Blue Moon” Odom, was denied a no-hitter when two A’s misplays were ruled base hits by a Baltimore hometown scorer. Both McGaha and Finley called the press box to complain, but to no avail. 82

During that same road trip, the A’s played before the smallest night crowd in Fenway Park history (2,056, on September 14), while the Beatles played before ten times as many screaming fans in Kansas City’s Municipal Stadium during their landmark U.S. tour.83 The A’s finished 1964 thirty games below .500 under McGaha, and in last place, yet he retained his job.

Entering the 1965 season, McGaha faced two daunting challenges: limited lineup pop after the A’s traded away their top home run hitter, Rocky Colavito, and a roster with eight first-year bonus babies, seven of whom McGaha was obliged to keep in the majors or risk losing to another team.84 That group included two very green future centerpieces of Oakland A’s teams of the 1970s: 19-year-old pitcher Jim “Catfish” Hunter and outfielder Joe Rudi. Former bonus baby Tony La Russa impressed McGaha in spring training, but was sent to the minors to get more playing time.85

Opening Day hoopla that included owner Finley riding around on the team’s new mascot, a mule named Charley O, and birds flying out of an automatic ball dispenser,86 couldn’t hide the fact that the A’s were terrible. They lost 11 of their first 13, with several players openly unhappy with McGaha’s decisions. First baseman Jim Gentile, in McGaha’s doghouse for a pre-season faux pas, was incensed when light-hitting Ken Harrelson was installed at first to start the season.87 Fireman John Wyatt, who’d set a major league appearance record the year before, complained McGaha was giving younger, less experienced pitchers playing time that should’ve been his.88 McGaha’s most questionable decision may have been moving Campaneris to the outfield, “convinced [he] is not suited to play short in the majors on a full-time basis.”89

On May 13, with the A’s losing badly in the last game of a 1-7 road trip, McGaha brought in Hunter for his professional debut.90 Four days later, McGaha became the first major league manager fired in 1965; “given a dose of hemlock-flavored kickapoo juice,” according to Arthur Daley of the New York Times.91 A’s beat writer Joe McGuff reported that McGaha was disliked by team’s veterans and Finley claimed the team could have won 20 of the 21 games they lost (versus only five victories), but others saw McGaha as a scapegoat for a lousy team.92

Years later, a tale emerged about an interchange between McGaha and Satchel Paige during the 1965 season. As the story went, McGaha asked Paige to run laps around a running track to stay in shape. Paige balked, telling McGaha “Running is for dogs and chickens. The chickens run away from the dogs and the dogs run after the chickens.”93 In fact, Paige signed with Kansas City in mid-September to pitch one final time, long after McGaha’s demise.

After killing time selling insurance and doing public relations work, McGaha joined the Triple-A Oklahoma City 89ers for the 1966 season, taking the reins for a Houston Astros affiliate that had dominated the Pacific Coast League the year before.94 With no returning regulars and their best players snapped up by the parent club (or traded), the 89ers finished 30 games below .500.95 In the fall, McGaha managed an Astros/Cincinnati Reds Florida Instructional League team that included Bernie Carbo, Nate Colbert, Doug Rader, Gary Nolan and 18-year-old Johnny Bench.

In 1967, McGaha led the 89ers to a .500 finish, then managed the Valencia Eagles in the Venezuela Winter League. Featuring a handful of Venezuelan and American major leaguers, the Eagles played before raucous home crowds policed by submachine gun-carrying guards.96 McGaha left Valencia with six games remaining to take on a new job; coaching for the Astros.97

For the next three seasons McGaha, handled first base coaching duties for manager Grady Hatton. McGaha was decidedly hands-on in 1968, helping Joe Morgan improve his double play efficiency, clubbing a snake on the basepaths at Dodger Stadium, and wrestling New York Met Tommie Agee to the ground during a bench-clearing brawl.98 McGaha capped off the year by winning the annual Grady Hatton golf tournament held in Beaumont, Texas.99

Like many ballplayers, McGaha excelled at golf. In 1951 he was called the best golfer on the Houston Buffaloes, then three years later, the Shreveport Sports’ finest.100 McGaha got a hole-in-one while managing for Mobile, won the Indians’ annual spring training tournament in 1961, and carried a seven handicap while with the A’s.101

As the 1960s drew to a close, McGaha began looking beyond baseball. He became a grandfather for the first time and unsuccessfully tossed his hat into the ring for a job as Missouri Valley Conference basketball commissioner.102 After the 1970 season, he left Houston to become the Director of Parks and Recreation for his adopted hometown of Shreveport.

Over the next eight years, McGaha led the expansion and modernization of city programs and facilities, and helped create the Independence Bowl, first held in Shreveport in 1976.103

During his first five years as Parks and Recreation Director, McGaha also served as president of Shreveport’s Double-A minor league club.104 McGaha handled GM responsibilities briefly and assisted in marketing for the Captains, a California Angels affiliate relocated from El Paso that passed to the Milwaukee Brewers and then the Pittsburgh Pirates.105

After leaving Shreveport Parks and Recreation, McGaha scouted regional prospects for the New York Yankees then spent three years heading up the Parks and Recreation department for neighboring Bossier City.106 McGaha later played a pivotal role in getting Shreveport’s new minor league ballpark, Fair Grounds Field, built in the mid-1980s; prompting one local reporter to suggest the stadium, or the street it was on, be named after him.107

In the early 1980s, McGaha divorced and re-married. Complications from a hip replacement robbed him of much of his mobility soon after,108 prompting his move to a retirement home in Grand Lake, Oklahoma. After a lengthy illness, McGaha died of a stroke on February 3, 2002, survived by his second wife, Linda Jo, two children by his first wife, and five grandchildren.109

McGaha’s legacy was an uneven one. In northern Ohio, he was considered a failure. Years after his departure, McGaha was the touchstone by which Cleveland sportswriters measured managerial incompetence.110 Cleveland reliever Frank Funk called McGaha “the worst manager I ever saw.”111 Catfish Hunter described McGaha as an overbearing, un-smiling drill sergeant.112 Yet some of McGaha’s former players genuinely admired him. Dick Donovan called McGaha “one of the finest managers I’ve ever pitched for.”113 Late-1980s Indians manager Doc Edwards identified McGaha, who he played for in both Cleveland and Kansas City, as a role model.114

To Shreveport and much of Arkansas, McGaha was a sporting icon. He’d reached the highest level in multiple sports, then returned to serve his community. After his death, the Shreveport Times called McGaha “an ambassador and spokesman for the game, an excellent teacher of the game’s fundamentals, a solid strategist, a man to be respected.”115 Arkansans thought so highly of McGaha they attached his name to the trophy given to the top American Legion outfielder in the Little Rock area in the 1960s, inducted him into the Arkansas Sports Hall of Fame in 1970 and enshrined him in the University of Arkansas Hall of Honor in 1990.116

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Darren Gibson and David Bilmes and checked for accuracy by SABR’s fact-checking team.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author utilized game accounts and background information reported in newspapers that covered sports at McGaha’s high school and the University of Arkansas (Arkansas Gazette, Northwest Arkansas Times, Arkansas Democrat and Hope Star) and local newspapers in Shreveport, Louisiana (Shreveport Journal and Shreveport Times). He also consulted MyHeritage.com, FamilySearch.com, Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, Statscrew.com, stathead.com and basketball-reference.com.

Notes

1 A few months after Mel was born, Bastrop, the birthplace also of soon-to-be major leaguer Bill Dickey, provided refuge to thousands left homeless by the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927. Betty Jo Harris, “The Flood of 1927 and the Great Depression: Two Delta Disasters,” Folklife in Louisiana website, https://www.louisianafolklife.org/lt/articles_essays/deltadepression.html, accessed April 14, 2023.

2 Orville Henry, “Notepad,” (Little Rock) Arkansas Democrat, November 18, 1990: 38. McGaha was the leading scorer in the 1943 Pulaski County boys’ basketball championship match and shared a best male athlete award for his senior class. “Jacksonville County Senior Cage Champs,” Arkansas Gazette, March 13, 1943: 11; “Graduation at Mabelvale,” Arkansas Gazette, June 1, 1943: 10.

3 “Fireflys Lose First Game, 5-4,” Arkansas Gazette, June 15, 1942: 6; “AOP, Tucker Win City League Games,” Arkansas Gazette, May 17, 1943: 6; “Tuckers Win on One-Hitter by Thornhill,” Arkansas Gazette, June 21, 1943: 7; “Reception Center Lose to All-Stars,” Arkansas Gazette, July 26, 1943: 6.

4 “Fate Plays Important Role in Mel McGaha’s Life,” Kansas City Star, June 14, 1964: 1B.

5 Charles Chandler, “1944 Razorbacks: The Forgotten Tragedy,” Charlotte Observer, April 2, 1994: 1.

6 Associated Press, “Porker Football; Basketball Ace Called by Army,” Corpus Christi Caller, February 28, 1945: 15; Associated Press, “Only 15 of 52 Remain on Arkansas Squad,” (Memphis, Tennessee) Commercial Appeal, February 25, 1945: 14.)

7 Associated Press, “Melvin McGaha Will Rejoin Porker Cagers,” Houston Chronicle, November 9, 1945: 34.

8 “Teepee Tenants,” Canton (Ohio) Repository, June 23, 1961: 15; Associated Press, “Mel McGaha Believes in Fundamentals,” Miami (Ohio) News, March 18, 1962: 23.

9 Associated Press, (Jersey City, New Jersey) Jersey Journal, “Donovan Picked on All-Invading Team,” March 9, 1946: 10; “Basketball Action in Color,” Look, April 2, 1946: 37.

10 McGaha’s standing as football team co-captain likely surely influenced his decision to pick the Cotton Bowl over the basketball at the Garden. Associated Press, “N.Y.U, Texas Stay Unbeaten,” Des Moines Register, December 18, 1946: 14.

11 George Leonard, “Mobile Manager McGaha Played All Nine Positions,” Nashville Banner, May 13, 1958: 19; “Fate Plays Important Role in Mel McGaha’s Life.”

12 United Press, “Arkansas Youth Promising End,” Blytheville (Arkansas) Courier News, September 2, 1944: 6; J. Roy Stockton, “Missouri Bows to Arkansas, 7-6; Porker Score on Blocked Punt,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 24, 1944: 16.

13 Immediately after his elbow became dislocated, McGaha instinctively pulled on his wrist to pop his elbow back into place. A doctor later told him that had he not done that, he might have lost the ability to throw a baseball for life. “Porker Sparkplug,” Northwest (Fayetteville) Arkansas Times, January 23, 1947: 8; “Mobile Manager McGaha Played All Nine Positions.”

14 Bob Dolgan, “M’Gaha Wins Job as Knicks’ Hatchet Man,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, December 15, 1961: 31.

15 McGaha played for the Fayetteville Merchants, whose opponents included a team of All-Stars headed by Negro League star hurler Satchel Paige. “New Fayetteville Baseball Team Begins Schedule,” Arkansas Gazette, May 18, 1944: 17; Associated Press, “Mel McGaha, Porker Athlete, Joins Buffs,” Tulsa World, June 2, 1948: 20; “Merchants Play Morrilton at 8:15 Tonight,” Northwest Arkansas Times, July 1, 1948: 7; Allan Gilbert Jr, “Satch Heads South Via Alaska,” Northwest Arkansas Times, September 1, 1965: 19.

16 “Mobile Manager McGaha Played All Nine Positions.”

17 “Mel McGaha Proud Pap of Baby Daughter,” Northwest Arkansas Times, October 30, 1947: 6.

18 Associated Press, “Arkansas Comes from Behind to Nip William-Mary, 21-19,” Spokane (Washington) Spokesman-Review, January 2, 1948: 10; Associated Press, “McGaha’s Run Tops Among Thrillers,” Hope (Arkansas) Star, April 15, 1948: 4; “Longest Interception Returns,” Arkansas Football website, https://arkansasrazorbacks.com/interception-returns/, accessed April 19, 2023.

19 Associated Press, “Hogs Host to Aggies Nine Today,” Arkansas Democrat, April 5, 1948: 7. McGaha was signed by Fred Hawn, who also signed fellow Ozark natives Lindy McDaniel and Wally Moon. Jim Bailey, “McGaha ‘Came to Beat You’,” Arkansas Gazette, January 14, 1970: 3B; Jack Fiser, “The Barber Chair,” Shreveport Times, July 19, 1958: 8-A.

20 “Baseball Long a Neglected Sport at the University, Hits the Comeback Trail,” Northwest Arkansas Times, June 6, 1947: 47; Associated Press, “University Beats Kansas Baseball Teams Two Games,” Hope Star, April 28, 1948: 4; Associated Press, “Razorbacks Stymie Hurricane Nine, 6-4,” (Oklahoma City) Daily Oklahoman, May 13, 1948: 36.

21 Alworth earned his three letters playing baseball, football and running track. Associated Press, “Alworth Joins Porkers’ Elite,” Tulsa World, May 22, 1960: 19.

22 McGaha debuted for the Buffaloes as a right fielder, playing alongside former major leaguer and World War II combat veteran Hal Epps. He went hitless in three at-bats in the two games he played. Associated Press, “Buffs Trim Rebs, 7-0, On Bryant’s 4-Hitter,” Tulsa World, June 14, 1948: 9; “McGaha Sold by Herd to Columbus Squad,” Houston Chronicle, June 19, 1948: 7.

23 McGaha’s roommate was also killed in the crash. The survivors included Elmer Schoendienst, brother of Cardinal second baseman Red. “Fate Plays Important Role in Mel McGaha’s Life.”; Halsey Hall, “It’s a Fact,” Minneapolis Morning Tribune, February 10, 1949: 21.

24 Jim Bailey, “McGaha ‘Came to Beat You’,” Arkansas Gazette, January 14, 1970: 3B; Joel Rippel, “The 1948 Duluth Dukes Bus Crash,” The National Pastime: Major Research on the Minor Leagues,” 2022, https://sabr.org/journal/article/the-1948-duluth-dukes-bus-crash/

25 “Mobile Manager McGaha Played All Nine Positions.”

26 “Pistons Play New York Here Tonight as New Era of Pro Basketball in Fort Wayne Gets Under Way,” Fort Wayne News-Sentinel, November 3, 1948: 25.

27 “M’Gaha Wins Job as Knicks’ Hatchet Man.” When McGaha stood up to an opponent who was pushing his roommate around on the court during a pre-season match, Lapchick was so impressed he told McGaha he’d made the team. “Kid,” said Lapchick, “we’ve had a lot of nice boys around here and we’ve never won anything. I figure we could use a rough-houser like you.” After McGaha got into a fight with an opposing player in another game, Lapchick cracked “it’s good to have a guy who gets in a fight occasionally.” Shelley Rolfe, “Diary of a Traveler to Baseball Meeting,” Richmond (Virginia) Times-Dispatch, December 6, 1959: 2-D.

28 McGaha did score 18 in one game against the last-place Providence Steamrollers, after which the New York Daily News claimed his “ball-hawking and general pestiferousness” made him a favorite of the 69th Street Armory crowd. Dick Young, “Knicks Kick Rollers 89-77 for Ailing Coach,” New York Daily News, January 27, 1949: 62.

29 Russ Needham, “Rookie Hopes Still Holding Up in Camp of Our Red Birds,” Columbus Evening Dispatch, March 28, 1950: 20.

30 “Cards’ Fabulous Farm System is Still Paying Dividends,” Montgomery (Alabama) Advertiser, June 12, 1949: 19.

31 “West Fork Cagers Win County Titles,” Arkansas Democrat, February 12, 1950: 13.

32 “Overtime Games Mark Play in Springdale Tourney,” Northwest Arkansas Times, February 2, 1952: 5; Jack Gallagher, “Dalls’ Sunset Provides Farm for West Point,” Houston Post, March 7, 1951: 16.

33 Associated Press, “Buffs Leave Cellar,” Galveston News, September 5, 1950: 14.

34 Joe Trimble, “Yanks Slug Buffs, 15-9; Mantle, DiMag Homer,” New York Daily News, April 9, 1951: 50; United Press, “Mel McGaha to Miss 1951 Season,” Waxahachie (Texas) Daily Light, April 27, 1951: 5.

35 Jack Gallagher, “McGaha, Survivor of a Bus Crash, Now Faces Crashes at Home Plate,” Houston Post, March 26, 1952: 21.

36 United Press, “Tulsa Downs Buffs in Game at Home,” Rogers County News (Claremore, Oklahoma), May 6, 1952: 6; United Press, “Necks Stretch Texas Margin,” Enid (Oklahoma) Eagle, May 17, 1952: 2.

37 The cash exchanged in the deal was claimed to be the largest ever paid for a ballplayer by a Texas League club. Lorin McMullen, “Buffs Get Sports’ Star for Estimated $30,000,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, December 4, 1952: 63.

38 McGaha had been serving as an assistant manager, helping Livingston with paperwork. “Livingston Undergoes Operation, McGaha in Saddle,” Shreveport Journal, May 20, 1953: 3B; Jack Fiser, “McGaha at the Wheel,” Shreveport Times, May 22, 1953: 4-C.

39 Jack Fiser, “The Inside Corner,” Shreveport Times, June 12, 1953: 12-A.

40 “Mel McGaha Believes in Fundamentals.”

41 “Mel McGaha Named Aide to Glen Rose,” Arkansas Democrat, September 19, 1952: 20; Associated Press, “McGaha Takes Collins Job at Arkansas A&M,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, September 3, 1953: 15.

42 Jack Fiser, “Piloting Loop’s Leader but One of Many Chores,” The Sporting News, April 28, 1954: 29.

43 Associated Press, “Mel McGaha New Shreveport Manager Succeeding Tavern Owner Livingston,” Muskogee (Oklahoma) Phoenix, December 3, 1953: 16.

44 Jack Fiser, “Sports’ Manager Has Fine Nucleus,” Daily Oklahoman, April 2, 1954: 59; Lorin McMullen, “Everything Click, It Seems Easy to Sports,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, April 18, 1954: 21; Jack Fiser, “Sports Win First Regular Season Title,” Shreveport Times, September 5, 1954: 1.

45 Jack Fiser, “A Great Year,” Shreveport Times, September 14, 1954: 13-A.

46 Career minor-leaguer Ray Knoblauch, father of Chuck, earned the win over Houston in game seven. “Knoblauch and Pringle Team to Defeat Houston,” Shreveport Journal, September 23, 1955: 13.

47 Jack Fiser, “The Inside Corner,” Shreveport Times, March 3, 1954: 4-B; “McGaha Resigns as A&M Cage Coach,” Hope Star, March 4, 1955: 17; “Arkansas A&M Looks for New Cage Coach,” Camden (Arkansas) News, March 5, 1955: 2; “Mel McGaha Believes in Fundamentals.”

48 Jack Fiser, “Lobby Hopping,” Shreveport Times, January 22, 1956: 1-D; “Annual Shreveport Free School,” The Sporting News, February 15, 1956: 36; John Wilson, “Only Injuries Could Cloud Astros Set Infield Picture,” The Sporting News, March 3, 1973: 22.

49 Guettler’s success was credited in part to his wearing glasses for the first time in his career. After hitting five homers off Houston Buffalo pitching over two games in mid-April, Guettler’s glasses disappeared from the locker room at Houston’s ballpark. McGaha claimed the spectacles had been stolen, and that it was an inside job. The crime, if there was one, was never solved. Bob Rives, Ken Guettler SABR biography, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/Ken-Guettler/; “McGaha Hints at Plot to Steal Slugging Outfielder’s Glasses,” Beaumont Journal, April 18, 1956: 20.

50 Based on author’s review of Shreveport newspaper accounts of games in which McGaha homered. “Hanlon’s 1-Hitter Stops Sports, 3-0,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, August 26, 1956: 37.

51 B.A. Bridgewater, “Telling the World,” Tulsa World, September 13, 1956: 50. Pitching in relief in one blowout, McGaha allowed a home run to 19-year-old Little Rock native Brooks Robinson. In that game, Robinson went 5-for-5 with a pair of home runs. “Sports Socked by Missions Twice 17-4, 5-4,” Shreveport Times, June 11, 1956: 8-A.

52 “Veteran Manager,” San Antonio Express and News, April 14, 1957: 39.

53 A steadfast opponent of segregation, Peters also found himself at odds with other Texas League owners, who had integrated their teams, albeit slowly. The owners of integrated teams felt at a disadvantage as they couldn’t bring their black ballplayers to play in Shreveport in 1956 and 1957 after the Louisiana legislature passed a law requiring all sporting events in the Pelican State to be segregated. Jeff Miller, “The 1950s Louisiana Law that Stalled Racial Progress in Texas Baseball,” April 15, 2022, Texas Monthly website, https://www.texasmonthly.com/arts-entertainment/texas-league-baseball-history-segregation/.

54 According to McGaha, “I was a free agent about 30 minutes from the time Bonneau Peters phoned me that Shreveport was out of the league until I was phone by Mobile and agreed to terms with them.” Jack Ready, “Every Now ‘n Then,” Arkansas Democrat, May 25, 1958: 21.

55 “Mel McGaha to Play in Cuban Winter Circuit,” Shreveport Journal, January 4, 1958: 7.

56 Associated Press, “Bears Rout Rocks, 9-1,” Birmingham Post-Herald, September 8, 1958: 11.

57 Bob Phillips, “Barons Rally, Defeat Mobile,” Birmingham Post-Herald, September 18, 1958: 26.

58 George Leonard, “Bears’ Pace Steady in Month of Travel,” The Sporting News, May 13, 1959: 33.

59 Charlie Roberts, “Mobile Lashes Crax on 16 Bingles, 14-3,” Atlanta Constitution, May 8, 1959: 41; Associated Press, “Late Slump Worries McGaha,” Nashville Banner, September 4, 1959: 26.

60 Alf Van Hoose, “Barons and Bears gird for hot war,” Birmingham News, September 8, 1959: 23; Charles F. Faber, Gordy Coleman SABR biography, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/Gordy-Coleman/

61 Cicotte was a great-nephew of Chicago Black Sox knuckleballer Eddie Cicotte.

62 Andy McCutcheon, “Toronto’s McGaha IL’s Manager of Year,” Richmond (Virginia) News Leader, October 1, 1960: 8; J.G. Taylor Spink, “Maz, Dan, Weiss Best in Big Time,” The Sporting News, January 4, 1961: 1.

63 During the 1960 season, McGaha had been rumored to be the next manager of the Indians and well as the next skipper of the San Francisco Giants. Shortly before the 1961 season began, he was identified in the press as a possible first manager of the 1962 expansion Houston Colt 45s. Ed McAuley, “Tribe Aid Planted in Wings – Just in Case Dykes Trips,” The Sporting News, March 8, 1961: 8; “As the Editor Views It,” Mobile Journal, July 1, 1960: 1; Murray Sinclair, “Cleveland Has High Plans for McGaha,” Shreveport Journal, April 6, 1961: 34.

64 Associated Press, “Mel McGaha Named to Succeed Dykes as Indian Manager,” Kansas City Star, October 2, 1961: 12.

65 Associated Press, “Cleveland Starts New Era of Baseball,” Shreveport Journal, October 3, 1961: 9. Helping McGaha in his efforts to turn the Indians around was a coaching staff that included fellow-Shreveport transplant Salty Parker, Ray Katt and pitching coach Mel Harder, a holdover from Dykes’ reign.

66 Bob Dolgan, “M’Gaha Gets Job of Curing Indians’ Ills,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, October 3, 1961: 27.

67 Associated Press, “’Too Many Lawyers on Club’ Former Indian Pilot Says,” Kansas City Star, October 2, 1961: 12.

68 In August of 1962, the Boston Globe claimed that McGaha agreed to take the job as manager on the condition that Paul “get rid of” Piersall, Temple and Power. Milton Gross, “Indians Weed Out Clubhouse Lawyers; Is Power the Next,” Boston Globe, March 30, 1962: 40; Clif Keane, “Tough Pilot or Clown, Indians About the Same,” Boston Globe, August 10, 1962: 18.

69 United Press International, “Romano’s 9th-Inning Homer Gives Indians Victory Over Baltimore,” Greenville (Ohio) Advocate, May 22, 1962: 9.

70 Hal Lebovitz, “Mel Often Flaunts Accepted Theories to Pull Out Wins,” The Sporting News, June 23, 1962: 5.

71 Bill Tanton, “McGaha Belongs to New School of Polished Pilots,” Baltimore Evening Sun, May 29, 1962: 31.

72 Attendance at Cleveland Municipal Stadium, 70,918, was also the largest for any Cleveland game since their 1954 AL championship season. Cleveland ultimately swept four doubleheaders from the Yankees in 1962, the most by a New York opponent since the Boston Red Sox swept four from the 1913 squad that was the first to be called Yankees. Hal Lebovitz, “Wigwam Jumpin’ with Joy Over Yank-Killers,” The Sporting News, June 30, 1962: 13.

73 During their swoon McGaha earned what the author has identified as his first ejection as a major league manager. McGaha was tossed on August 1 for objecting to a balk called on Indians pitcher Ruben Gomez while second baseman Jerry Kindall was trying to pull off a hidden ball trick. Associated Press, “It’s Dog Days for Sad Tribe,” Lima (Ohio) Citizen, August 2, 1962: 32.

74 Bob Dolgan, “Driving McGaha is Off to Brilliant Start,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 8, 1962: 31.

75 Larry Merchant, “Tribe Figures Puzzle – Even to New Chief Birdie,” Philadelphia Daily News, March 23, 1963: 30. Ironically, just before the All-Star break, Al Silverman, the editor of SPORT magazine had called McGaha the “safest” (least likely to get fired) manager in the majors. Al Silverman, “Inside Sport,” St. Cloud Times, July 5, 1962: 15.

76 Bob Maisel, “The Morning After,” Baltimore Sun, August 20, 1962: 15.

77 Hal Lebovitz, “M’Gaha Out, Paul Seeks New Pilot,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, October 1, 1962: 29.

78 “Mel McGaha Gets Job with Kansas City,” Appleton (Wisconsin) Post-Crescent, October 7, 1962: 15; “Good Deal,” Alliance (Ohio) Review, October 17, 1962: 17.

79 “Sales Add Up on A’s Tickets,” Kansas City Star, March 12, 1963: 10; Ernest Mehl, “A’s Ditch Drab Duds; They’ll Dazzle Fans in Bright Green, Gold,” The Sporting News, February 9, 1963: 29. The A’s were the first major league team to wear a color other than white, gray or light blue since the Chicago White Sox’ dark blue uniforms in 1931. “Kansas City Athletics Uniform History,” MLBCollectors website, https://mlbcollectors.com/KCAjerseys.php, accessed May 5, 2023.

80 During spring training, one sportswriter referred to the perennial second-division A’s as “short on playing talent, but … loaded with coaches.” Chauncey Durden, “Disa and Data,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, March 21, 1964: 16.

81 Joe McGuff, “McGaha Hints He’ll Be More Forceful Than Lopat,” Kansas City Times, June 12, 1964: 18.

82 According to Hatter, “Finley was decent and civil,” but “McGaha was mad, and used a few bad words.” Associated Press, “Scorer Defends Hit Calls,” Elmira (New York) Star-Gazette, September 13, 1964: 38.

83 Hy Hurwitz, “Only 2056 Watch A’s Win,” Boston Globe, September 15, 1964: 17; Robert K. Sanford, “Police Hold Tide of Beatlemania,” Kansas City Times, September 18, 1964: 1; Briana O’Higgins, “PHOTOS: Remembering the Beatles Concert in Kansas City 50 Years Ago,” Radio Station KCUR website, September 16, 2014, https://www.kcur.org/community/2014-09-16/photos-remembering-the-beatles-concert-in-kansas-city-50-years-ago

84 Joe McGuff, “Should A’s Toss Catfish Back? It’s Stickler on Friday’s Line,” The Sporting News, March 27, 1965: 25. McGaha faced those challenges with a coaching staff that included two wizened Hall of Famers, Luke Appling and Gabby Hartnett, and one future one, 33-year-old Whitey Herzog, in his first coaching position.

85 McGaha’s support for La Russa dated back to 1963, when as an A’s coach, he spent hours hitting ground balls to the youngster. Joe McGuff, “Green’s Touchy Thumb Proving Sore Spot to A’s,” The Sporting News, April 3, 1965: 12; “About Tony La Russa,” Baseball Hall of Fame website, https://baseballhall.org/hall-of-famers/la-russa-tony, accessed June 7, 2023.

86 Festivities at the A’s home opener also included Miss U.S.A, Kansas City native Bobbie Johnson, throwing out the ceremonial first pitch and briefly serving as a batgirl. Paul J. Haskins, “A’s and Their Fans Chilled in Opener,” Kansas City Times, April 13, 1965: 1.

87 Gentile had made an obscene gesture to a heckler while circling the bases during an exhibition game, drawing a $500 fine from McGaha and a promise it’d be doubled if he did it again. Furious, Gentile shot off a telegram to Finley asking to be traded. Dick Young, “Gentile to A’s: ‘Trade Me!’,” New York Daily News, April 4, 1965: 35C; Joe McGuff, “Gentile Busts Out of A’s Doghouse with His HR Bat,” The Sporting News, May 1, 1965: 15.

88 Joe Reichler, “A’s Relief Star Gets Little Chance to Work,” Passaic (New Jersey) Herald-News, April 29, 1965: 31.

89 Joe McGuff, “Swift Campy Slated for Job as A’s Picket,” The Sporting News, May 8, 1965: 21.

90 Two weeks earlier, McGaha had noted Hunter “had a lot of poise” then admitted “we might just as well lose with the kid and give him some experience.” Hunter pitched two scoreless innings. Dana Mozley, “A’s Catfish Worth 75G Despite Shotgun Pellets,” New York Daily News, April 29, 1965: 128.

91 Arthur Daley, “Reliable Panacea,” New York Times, May 18, 1965: 45.

92 Joe McGuff, “Alvin Dark Offers A’s Strong Leadership,” Kansas City Star, February 24, 1966: 24; “With Trips, Losing Takes Some Doing,” Binghamton (New York) Evening Press, May 21, 1965: 8.

93 Dink Carroll, “Playing the Field,” Montreal Gazette, August 3, 1968: 24.

94 McGaha was recommended by former 89ers manager Grady Hatton, who’d recently been promoted to become manager of the Houston Astros. “Satch Heads South Via Alaska.”; Bill McIntyre, “Basketball: Shoes & Feet,” Shreveport Times, November 28, 1965: 2-D.

95 “T-Cubs to Open ‘Far-Flung’ PCL,” Kitsap (Washington) Sun, April 15, 1966: 14; “McGaha Never Had a Chance,” Oklahoma City Oklahoman, September 7, 1966: 13.

96 Bill McIntyre, “’El Beisbol’,” Shreveport Times, February 14, 1968: C-1.

97 Eduardo Moncada, “Spanky Directs Imported Gang to 6-4 Victory,” The Sporting News, January 27, 1968: 37.

98 “Newcomers Getting Credit for Astros Double Plays,” Tyler (Texas) Morning Telegraph, April 5, 1968: 20; Jim Zofkie, “Astro Wynn Nearly “Snake Bit,” Dayton (Ohio) Journal Herald, May 21, 1968: 12; Associated Press, “If Only He Had Kept Quiet,” Mattoon (Illinois) Journal Gazette, August 8, 1968: 6.

99 John Wilson, “Astros’ Rusty Real Swinger Under Lights,” The Sporting News, November 30, 1968: 48.

100 Jack Gallagher, “Patrick Could Turn That Record Around,” Houston Post, March 15, 1951: 18; “Shreveport to Raise 1952 Pennant Saturday Night,” Shreveport Journal, June 6, 1953: 6.

101 “Hole in One,” Daytona Beach Morning Journal, April 9, 1958: 12; Murray Sinclair, “Cleveland Has High Plans for McGaha,” Shreveport Journal, April 6, 1961: 34; “Best ‘Big Name’ Field Developing for Friday’s Baseball-Golf Tourney,” Tampa Bay Times, March 11, 1965: 40.

102 Volney Meece, “Spring Training Blahs Start at 7 a.m.,” Daily Oklahoman, March 29, 1969: 43; Associated Press, “Ex-Texas Tech Coach New Commissioner,” Mexia (Texas) News, July 11, 1969: 8.

103 Kent Heitholt, “Bowl founders fought odds,” Shreveport Times, November 23, 1986: 1.

104 “McGaha Leaves Baseball Briefly but Heads New Shreveport Club,” Little Rock Arkansas Gazette, January 24, 1971: 18.

105 In 1974, McGaha’s son Fred, a fleet-footed outfielder from Louisiana Tech drafted by the Cardinals in the 1972 MLB draft, became a member of the Captains and later joined their public relations department. “Caps Won’t Appoint New GM,” Shreveport Journal, July 13, 1971: 8; “Fred McGaha Joins Caps’ Front Office,” Shreveport Journal, June 2, 1975: 21.

106 Bill McIntyre, “Mets’ Davis does Captains in, 5-4,” Shreveport Times, April 18, 1979: C-1; Dick Young, “Young Ideas,” The Sporting News, April 28, 1979: 2.

107 Nico Van Thyn, “The new stadium: A progress report,” Shreveport Journal, July 4, 1985: 1C; Nico Van Thyn, “And Hemard was there to see it,” Shreveport Journal, July 6, 1985: 5A.

108 “Mel McGaha still battling in LSU Hospital,” Bossier Press Tribune, October 3, 1984: 7.

109 “Former local parks and recreation director dead,” Shreveport Times, February 6, 2002: 2C; “Obituary Ads,” Monroe (Louisiana) News-Star, February 10, 2002: 18A.

110 See, for example Bruce Jenkins, “Where are the Indians?” Lancaster (Pennsylvania) Intelligencer Journal, October 24, 1995: 26, and Ritter Collett, “Gabe riding a ‘wild one’,” Dayton (Ohio) Journal Herald, August 5, 1975: 6. Disdain for McGaha in the Cleveland sports community even crossed into other sports. In decrying abuse heaped by disgruntled fans on head coach Bill Belichick in 1995, Browns owner Art Modell cracked that even McGaha was targeted for less abuse. Bart Hubbuch, “Modell makes point: Don’t mess with Bill,” Akron Beacon Journal, August 19, 1995: 47.

111 Bob Dolgan, “Funk Blasts McGaha: Chisox Rout Indians,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 17, 1962: 6.

112 “Fond memories linger of that first training camp,” Newark (New Jersey) Star Ledger, March 14, 1985: 81.

113 Dennis Lustig, “Whatever happened to … Dick Donovan,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 23, 1981: 47.

114 Sheldon Ocker, “Edwards well-prepared for biggest assignment,” Akron Beacon Journal, April 4, 1988: Baseball-2.

115 Nico Van Thyn, “McGaha’s death marks end of era,” Shreveport Times, May 2, 2002: 7C.

116 “Tournament Slated at Conway Field,” Little Rock Arkansas Democrat, July 25, 1967: 11; Associated Press, “Arkansas Quartet Admitted to Hall,” Northwest Arkansas Times, January 24, 1970: 7; “Razorback Hall of Honor to Include 6 Former Hogs,” Tulsa World, September 11, 1990: 13.

Full Name

Fred Melvin McGaha

Born

September 26, 1926 at Bastrop, LA (USA)

Died

February 3, 2002 at Tulsa, OK (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.