Benny Ayala

Benigno Ayala lives up to his given name, which means “kind” or “friendly.” Following a productive career as a role player, he has bestowed greater gifts on the baseball world, through his work with the Baseball Assistance Team (BAT). Quite a few of his fellow Puerto Rican pros have fallen on hard times since they left the game. “There are really sad stories,” said Ayala in 2009. “And most of them are unknown, because ballplayers are proud. They don’t like to ask.”1 Ayala played five full seasons in the majors and parts of five others from 1974 to 1985. He qualified for a good pension and does not have to worry about life’s necessities – now he is a voice for those in need.

In his playing days, the outfielder wasn’t known for his defense, but he was a pretty fair batting threat in platoon. In its glory years, the Baltimore organization understood the importance of “deep depth,” as manager Earl Weaver called it in 1979. Pitcher Steve Stone detailed the concept in Tales from the Orioles Dugout.

“They were a team that pretty much understood that the spare parts of a baseball team determine whether you win or lose. It’s going and getting . . . [a] Benny Ayala. And then it’s up to the manager after you get Benny Ayala to realize that . . . when they put soft-tossing lefthanders in the game, Benny was good for two hits. Earl put him in a situation where he could be successful. So Hank Peters went and got him, and Earl used him correctly.”2

Ayala came to the plate 951 times in his big-league career, and 86 percent of those appearances were against lefties. It’s no surprise that 35 of his 38 regular-season homers came off southpaws – as did his crowning blow as a pro, his two-run shot off John Candelaria in Game Three of the 1979 World Series.

Benigno Ayala Félix was born on February 7, 1951, in Yauco, a town in southwestern Puerto Rico. He was the first of two sons born to Benigno Ayala and Lillian Félix (there was also a half-brother). The island has sent over 300 men to the majors over the years, yet only three others have hailed from Yauco. The first was pitcher Tomás “Planchardón” Quiñones, a longtime local star who pitched briefly in the Negro Leagues in the 1940s. After Ayala came Mario Ramírez (1980-85) and Mike Pérez (1990-1997).

Ayala himself did not start playing baseball until the age of 11, but in retrospect, he saw some benefits from it. In 2010, he said, “If you start late, you don’t get bored. And when you grow, you have to go through a process of adjustment. I asked guys like Tom Seaver and Rusty Staub about it.”

On January 28, 1971, the New York Mets signed Ayala as a free agent (the amateur draft did not include Puerto Rico until 1990). The scout was Nino Escalera, who covered Latin America for the Mets. “I was in my first year at Rio Piedras Junior College. Whitey Herzog came to Puerto Rico. He was with the Mets at the time. Many years later, Nino told me and Angel Cantres that Whitey said, ‘Go as high as $125,000.’ He didn’t give us the money – he gave us $7,000!”

Escalera, who died in 2021 aged 91, was 80 when Ayala was originally interviewed. Ayala observed, “You know what else he told me? ‘Benny, out of all the guys I signed, you’re the only one who has helped me.’”

Ayala’s first pro team in the US was Pompano Beach in the Florida State League. He hit .279 with 8 homers and 34 RBIs in 63 games, which won him promotion to Visalia in the California League (high A). In the winter of 1971-72, he played in the Puerto Rican Winter League for the first time. “Nino Escalera was a coach for the San Juan Senadores, Roberto Clemente’s team. Angel Cantres went to San Juan after he signed with the Mets, but I didn’t. I said, I’ll see what I can do in the US, then I’ll see who’s interested. I’ll go to a club where I can develop. Arecibo was in the cellar. Cantres had more competition with San Juan.”

Returning to Visalia in 1972, Ayala hit 19 homers, second on the club behind Ike Hampton’s 21. He also had 66 runs batted in, one fewer than Greg Harts (who, like Hampton, appeared very briefly with the Mets). Visalia is an agricultural town with a large Hispanic population, but there were plenty of times when Ayala didn’t feel welcome. “We lived in a bad neighborhood called ‘Sin City’ but it was the only thing we could afford. People threw rocks at us. I remember waiting in a barbershop, and when my turn came, they said, ‘We don’t cut that kind of hair.’ The team owners were good people, though. I remember they owned a chain of hot-dog stands.”

Ayala continued to climb the ladder steadily. In 1973 he was with Memphis (Double A). Serving frequently as a designated hitter, he led the team in home runs (17) and was second in RBIs (68). That winter he led the Puerto Rican league in homers for the first time, as his 14 tied with Jerry Morales. He also tied Jay Johnstone for the league lead in RBIs with 46 and hit .340. To emphasize how strong that circuit was then, the four men who finished ahead of him in the batting race were George Hendrick, Chris Chambliss, Mickey Rivers, and José Cruz, Sr. Yet Ayala won the MVP award.

Ayala did well in spring training 1974, hitting homers off veterans like Woodie Fryman and Bob Gibson. He wasn’t quite ready, though, and Cleon Jones did not take well to an experiment in center field. Near the end of camp the Mets sent Ayala down to their top affiliate, Tidewater. Here too he was the club leader in homers (11) and RBIs (40). The big club called him up in August after Jones got hurt; to make room, pitcher Jack Aker went on the disabled list. Ayala still has the bat he borrowed from Joe Nolan, his teammate with the Tides and later the Orioles.

With that bat, on August 27, Ayala made a memorable big-league debut at Shea Stadium. Batting sixth in the lineup, he stepped in against Houston’s Tom Griffin (a righty!) with one out and nobody on in the second inning. He pulled a high fastball – as he kept repeating on Ralph Kiner’s postgame show, Kiner’s Korner – down the line in left field. The ball stayed inside the foul pole, and Ayala became the first National Leaguer to homer in his first big-league at-bat since Cuno Barragan in 1961. Of course, that made him the first Met to do so too (not to mention, the first Puerto Rican).

A contributor to the Ultimate Mets fan website provided some extra detail. “We were sitting in the left field mezzanine at Shea among this group of 10 or 12 of Benny Ayala’s cousins and extended family who were thrilled to see him in his first major-league game. When he homered in his first at-bat they went BERSERK, hugging and kissing everyone around, including me and my father of course. It was a great memory that I was able to recount with my dad that always drew a smile.”

The rookie did not live with family, however, and although fellow Puerto Rican Félix Millán was present, he remembers that his most helpful teammates were John Milner and Jones. Manager Yogi Berra also did not stack up well against Weaver in Ayala’s estimation. “He was always laughing, he didn’t pay too much attention to the game.”

Ayala did not see any big-league action in 1975. The Mets acquired Dave Kingman in February, which severely impaired his chances of making the big club. In fact, he played just 65 games for Tidewater, missing a big chunk of the early season after Rochester’s Bob Galasso broke his hand with a pitch.

In the winter of 1975-76, Ayala led the Puerto Rican league in homers once again with 14 in 60 games. He finished in a four-way tie for second in RBIs with 39. Coming off this very strong effort, he made the Mets roster in spring training 1976. The team’s new manager was Joe Frazier, his skipper at Visalia, Memphis, and Tidewater. Ayala was not in the lineup on Opening Day but started the next two games. He would get just two more starts over the remainder of April and May, however, and he got only three hits in 26 at-bats (including a pinch-hit homer off Jack Billingham, his last off a righty in the majors). New York then called up Jack Heidemann and sent Ayala back to Tidewater, where he hit just .225 with 12 homers and 48 RBIs.

On March 30, 1977, New York traded Ayala to the St. Louis Cardinals in exchange for second baseman Doug Clarey, whose big-league career comprised nine games scattered across the ’76 season. Ayala spent the bulk of 1977 with New Orleans in the American Association, where he had a good year (.298/18/73). The Cardinals called him up in September, but he got into just one game, singling in three at-bats.

The Cardinals had a new Triple-A affiliate in 1978, Springfield, but Ayala spent only part of the season there – he went to Columbus in the Pittsburgh organization on loan. As the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette wrote that August, “Columbus was so short of talent that it borrowed players from other minor-league clubs. Players like Hector Torres, an infielder, and Benny Ayala, an outfielder who has a problem. He can’t catch a fly ball.”3 Ayala hit .340 for the Clippers in 59 games, though, lifting his overall mark for the year to .299. He totaled 11 homers and 56 RBIs.

On January 16, 1979, Ayala got the best break of his career. The Cardinals traded him to Baltimore for Mike Dimmel, another player whose big-league career was quite limited (39 games from 1977 to 1979). Ayala had considered going to play in Japan with the Taiyo Whales, but Doc Edwards, his manager in Puerto Rico, was also the manager at Baltimore’s Triple-A team, Rochester.4 Edwards persuaded Ayala to stay, farm director Clyde Kluttz liked what he saw too, and the Orioles called him up at the end of April after Doug DeCinces got hurt.

Earl Weaver used Ayala sparingly in ’79, but he benefited from the AL’s designated-hitter rule. In 86 at-bats across 42 games, he hit 6 homers, drove in 13, and hit .256. He had his only two-homer game in the majors on June 10 at Memorial Stadium. Both were solo shots off his former Mets teammate, Texas Rangers lefty Jon Matlack.

Weaver did not use Ayala in the American League Championship Series, but he got six at-bats in four games during the World Series. He singled off John Candelaria in his first at-bat in Game Three before reaching the Nuyorican for his homer. That blow brought the Orioles within a run at 3-2, and they proceeded to knock out Candelaria in the fourth inning. During that rally, righty Enrique Romo came out of the bullpen, and so Al Bumbry hit for Ayala.

The Associated Press write-up said, “Ayala also didn’t know he was starting until he saw the lineup posted in the clubhouse. Ayala admitted that he never knows when Weaver is going to use him. ‘He doesn’t play me against certain lefthanders,’ Ayala said. ‘It’s mostly if I can hit a certain lefthander.’” Many observers thought the lineup was unconventional, but Earl said, “It was one that helped us get here in the first place. . . . Benny has done that for us a number of times.”5

Ayala enjoyed his best season in the majors in 1980 (.265/10/33 in a career-high 76 games). Always thinking positively, he said, “I don’t mind my role here. I always have a chance to swing the bat with the Orioles and the way Earl uses me is decent.” Frank Robinson, then a Baltimore coach, said, “Benny uses his time wisely, watching and studying the pitchers. He’s not afraid to ask somebody about a certain pitcher either.”6

Ayala’s most dramatic hit that year may have come on September 5 at Memorial Stadium. This could have been the game described in a 1996 article in the Los Angeles Times about Earl Weaver’s golden hunches. “One day, Weaver walked up to [pitching coach Ray] Miller and said, ‘Ray, Benny Ayala. Don’t forget that, Benny Ayala.’ That night, Ayala hit an eighth-inning pinch homer. ‘It just made sense to me in those days . . . to know if I had a hitter sitting on the bench in a situation that was hitting that pitcher good,’ Weaver said. ‘So I made up my lineups accordingly.’ ”7 The three-run blow off Oakland lefty Bob Lacey brought the Orioles within a run at 6-5, and they won it 8-7 with another three runs in the bottom of the ninth.

In the strike season of 1981, Ayala served mostly as a platoon DH with Terry Crowley. During 1982 he was part of a three-man contingent in left field with John Lowenstein and Gary Roenicke. In his book Weaver on Strategy, Earl said, “By matching your bench-players’ strengths to your starters’ weaknesses, you can create a ‘player’ of All-Star caliber.” He likened the trio’s total output to having a Reggie Jackson in the lineup.8

That July Ayala told Steve Wulf of Sports Illustrated, “I try to think ahead of time. Say, we are playing Chicago in two weeks. I think how the lefthander pitched me the last time. Sitting on the bench I have a lot of time to think. I try not to be surprised.” Another line in the same article showed his Zen-like calm. On May 19 he hit a three-run homer after a rain delay of an hour and 21 minutes. “When asked if he thought he was in a tough spot, having to face a two-strike count after sitting for so long, Ayala replied, ‘Not really. I just felt like I was pinch-hitting for myself.’” 9

Wulf’s piece was strewn with juicy quotes on Ayala. Earl Weaver said, “He’s so good he knocks himself out of games. I’ll start him against a lefthander, and he’ll hit a three-run homer off him. Then they’ll bring in a righty, and Benny’s back on the bench.” According to Lowenstein, Ayala was “the most profound player on the Orioles. ‘He will sit there, arms folded, for eight innings. If he’s going to hit, I’ll ask him what he’s looking for. He’ll say, ‘Something white. Coming through.’”10 Indeed, Ayala (like many Caribbean players) didn’t walk or strike out much – he got his hacks.

“I always try to take three swings,” Ayala said that summer. “I don’t think the hitter should give the pitcher a strike by taking.” With the arrival of Dan Ford, Ken Singleton had moved from right field to full-time DH, leaving Ayala with spot duty. Yet as always, he stayed positive. “Sure I would like to play more. But the important thing is to stay ready and then do your job when you’re called on.”11

In 2010 Ayala said, “I suffered a lot in the big leagues. It was hard for me to accept my role, but I accepted it quietly. If I don’t play every day, I have it in my mind that I have to work harder. Rod Carew asked me one time, ‘Benny, why are you over there by yourself? Don’t you want to talk?’ I told him I don’t have time. I worked. I studied, so when I get that opportunity against Ron Guidry, I can say, ‘I’m ahead of you.’” Ayala did far better than most against “Louisiana Lightning” – 9-for-28. Changeup artist Geoff Zahn was just his meat (11-for-30 with two homers), but the lefty whom Ayala owned was Mike Caldwell (11-for-21 with three HRs).

Ayala remained in his reserve role with the O’s in 1983, but his effectiveness diminished, as he hit just .221. “I was a little disappointed with Joe Altobelli [who succeeded Weaver], he didn’t give me a chance. Then when he knows he needs me for the postseason, he put me up against John Montefusco, a righty with that overhand curve.”

Ayala hit a sacrifice fly in his only at-bat in the ALCS against the White Sox, capping the three-run 10th-inning rally that won Game Four and the series for Baltimore. He also made his lone at-bat in the 1983 World Series count. In the seventh inning of Game Three, pinch-hitting for Jim Palmer, he lined a single to left off Steve Carlton, past a diving Mike Schmidt. Rick Dempsey scored the tying run. Ayala then scored the go-ahead run, which would stand up as the margin of victory.

When asked about having a World Series ring, Ayala said, “Juan González turned down $150 million from Detroit because he thought there wasn’t a chance for a ring. He should be in the Guinness Book of Records for that!

“You’re on top. You’re a champion. Even now, I’m signing autographs, and people request that I put ‘1983 World Series Champ’ after my name. I’m lucky that I played with legends – six Hall of Famers.”

In 1984 Ayala joked about his infrequent playing time. After getting just four at-bats in the month of June, he said, “I’m an eclipse player. You don’t see me very often.”12 He hit just .212 for the year, and the Orioles announced in late September that they would not offer him a contract for 1985. Bumbry and Singleton were also part of the housecleaning.

Spring training also came and went without any offers. Even Ayala thought it might be the end of the line. “So what’s left?” he said. “Mexico. And I don’t look at myself as a Mexican League player.13 Looking back, he thought he should have paid his own way to camp, as he remembers players like Rob Picciolo and Kurt Bevacqua did.

On April 19, 1985, though, the Cleveland Indians signed the veteran to a minor-league deal. Although he went just 7-for-46 with the Maine Guides (Portland), the Indians called him up in May. Just days after he made it back, he missed a fly ball against the Boston Red Sox – but then drove in the game-winning run. Manager Pat Corrales said, “Benny looked a little ugly in left field, but he was Robert Redford at the plate.”

Ayala spent the rest of the season with Cleveland, hitting .250 (19-for-76) in 46 games. “When I learned to hit to right field, I was 34 years old. I was a low-ball hitter. I liked to uppercut, even in street fights!” His last big-league homer came off Jimmy Key at Toronto’s Exhibition Stadium on September 4. The Indians made him a free agent in November 1985, and Ayala’s big-league career ended.

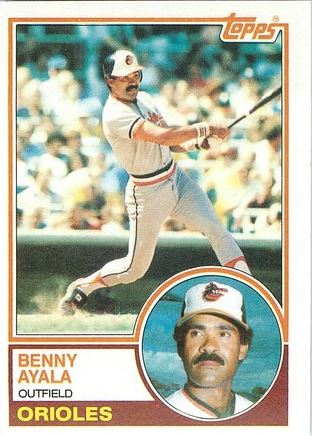

In December 2009, Ayala responded to blogger Bo Rosny’s request for stories about his baseball cards. One anecdote captured a key part of his approach to the game. “In one of them the picture was taken in Chicago that I like a lot; Brooks Robinson [then an Orioles announcer] told me that I was looking good. That was a perfect day to take the picture. He said, ‘Looking good, Benny, in case you have a bad game today.’

“After that I always shave before the game, good haircut, shine shoes, complete clean uniform, brand-new hat. In case I have a bad game, always looking good.”14

In the winter of 1985-86, Ayala returned to the Puerto Rican Winter League after several seasons away. He regretted the hiatus. “After I established myself with the Orioles, I didn’t go back. Relatives told me I was a little bored with the game. It was foolish. I should have played. I could have gone over 100 homers, I’d be one of the few there.” He finished with 68 homers in his PRWL career.

In 1989 Ayala came back to play with the West Palm Beach Tropics of the Senior Professional Baseball Association. One of his teammates was Tim Stoddard., whose career had overlapped with Ayala’s in Baltimore from 1979 through 1983. Ayala recalled, “I went there, I’m a low-mileage player. How can a player like me be injured? I hit very good, but one day I chased a fly ball and didn’t get it. [Manager] Dick Williams said, ‘We aren’t going to stick with you.’”

After his playing days finally ended, Ayala got an interview with Doug Melvin about a job in the Orioles chain but went back home to Puerto Rico. For a couple of years he was batting coach with Arecibo, “but there was not much money, $1,200 a month, and I was nearly killing myself driving.” After that, “I managed a couple of amateur teams, but they were not easy to handle.”

Ayala was married in 1971 to Esperanza “Eppie” Martínez. “I was always visiting her when I was in college. I was in love. I didn’t like school much!” The Ayalas had four children: sons Benigno III, Luis Mario, and Melvin, plus daughter Jesica.

In subsequent years, Ayala’s main endeavor became his professional network. His goal: to help retired Puerto Rican players in such areas as pensions, health insurance, celebrity baseball clinics, training clinics for children, and more. In November 2007 Ayala (in tandem with the Calero & Sullivan Baseball Management firm) held a groundbreaking meeting with 118 former pros from the island and the Major League Baseball Players’ Alumni Association. As a result, the Baseball Assistance Team was able to offer financial and medical support to various men who needed it. Ayala also got involved with setting up memorabilia signings to bring the players some additional money. His network came to include around 250 pros.

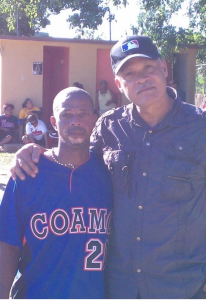

Ayala’s role as BAT’s liaison to the Puerto Rican community brings him and his fellow boricuas much joy. He helped his old teammate Angel Cantres after Angel lost a leg following a work-related accident in 2001. After former minor-league pitcher Jacinto Camacho received a new artificial leg to replace his homemade prosthesis, he walked off the plane home to greet his family and completely forgot about his wheelchair. “Times like these are when I know that the work I do with BAT really makes my life worthwhile,” Ayala said.15

In the summer of 2009 Ayala also reached out to former big-league outfielder Ricky Otero. Otero, who had fallen into alcohol and drug addiction, was living homeless in Cancún, Mexico. Though Otero subsequently denied the report, Ayala was able to get him into a rehab program in New York.16 As of 2024, Otero was doing well in Vega Baja, Puerto Rico.

In the summer of 2009 Ayala also reached out to former big-league outfielder Ricky Otero. Otero, who had fallen into alcohol and drug addiction, was living homeless in Cancún, Mexico. Though Otero subsequently denied the report, Ayala was able to get him into a rehab program in New York.16 As of 2024, Otero was doing well in Vega Baja, Puerto Rico.

Ayala, who turned 73 in 2024, remains actively involved in his professional network and on social media. He dresses with the same attention that he did to looking sharp in uniform. He is a cheerful and chatty man, but his baseball memories feature a serious undercurrent. He said, “Earl Weaver respected you as a major-leaguer. Some people had to be on the field first, but still I feel, ‘Here they treat everyone the same.’ I was very proud to wear that big-league uniform, with that Orioles name up front.”

This biography was originally published in 2010. It was subsequently updated for Puerto Rico and Baseball (SABR, 2017) and again in 2024.

Acknowledgments

Grateful acknowledgment to Benny Ayala for his memories (telephone interview, May 2, 2010). All quotations that are not otherwise attributed come from this interview.

Continued thanks to SABR member Jorge Colón Delgado (Puerto Rican statistics).

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted retrosheet.org, ultimatemets.com, and caleroandsullivan.com, as well as Crescioni Benítez, José A., El Béisbol Profesional Boricua (San Juan, Puerto Rico: Aurora Comunicación Integral, Inc., 1997).

Photo Credit

Benny Ayala with Ricky Otero, courtesy of Benny Ayala.

Notes

1 Carlos Rosa Rosa, “Benigno con el prójimo,” El Nuevo Día (Guaynabo, Puerto Rico), October 16, 2009.

2 Louis Berney, Tales from the Orioles Dugout (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing LLC, 2004), 147.

3 Charley Feeney, “Columbus Turmoil Might Spell Peterson’s Demise,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, August 8, 1978: 13.

4 Steve Wulf, “It’s the Right Idea for Left,” Sports Illustrated, July 12, 1982.

5 Associated Press, “Baltimore Offense Is Ignited,” October 12, 1979.

6 Ken Nigro, “Hitting Or Sitting, Ayala Happy,” The Sporting News, August 2, 1980: 37.

7 Jason LaCanfora, “Beyond tantrums, was hidden Weaver,” Los Angeles Times, August 4, 1996.

8 Earl Weaver and Terry Pluto. Weaver on Strategy (New York: Collier Books, 1984), 26.

9 Wulf, “It’s the Right Idea for Left.”

10 Wulf, “It’s the Right Idea for Left.”

11 Ken Nigro, “Benny Always Fit as Bird in Pinch,” The Sporting News, August 9, 1982: 27.

12 Robert W. Creamer, “They Said It,” Sports Illustrated, August 27, 1984.

13 Associated Press, “Indians won’t be sending Ayala to Mexico,” May 19, 1985.

14 http://borosny.blogspot.com/2009/12/one-more-card-story-from-benny-ayala.html

15 Baseball Assistance Team, Winter 2008 newsletter (mlb.mlb.com/mlb/downloads/y2009/bat/bat_winter_2008_newsletter.pdf)

16 “Ricky Otero: de Grandes Ligas a indigente en Cancún,” El Universal (Mexico City, Mexico), September 4, 2009. “Madeja de Contradicciones,” Primera Hora (Guaynabo, Puerto Rico), March 22, 2010.

Full Name

Benigno Ayala Felix

Born

February 7, 1951 at Yauco, (P.R.)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.