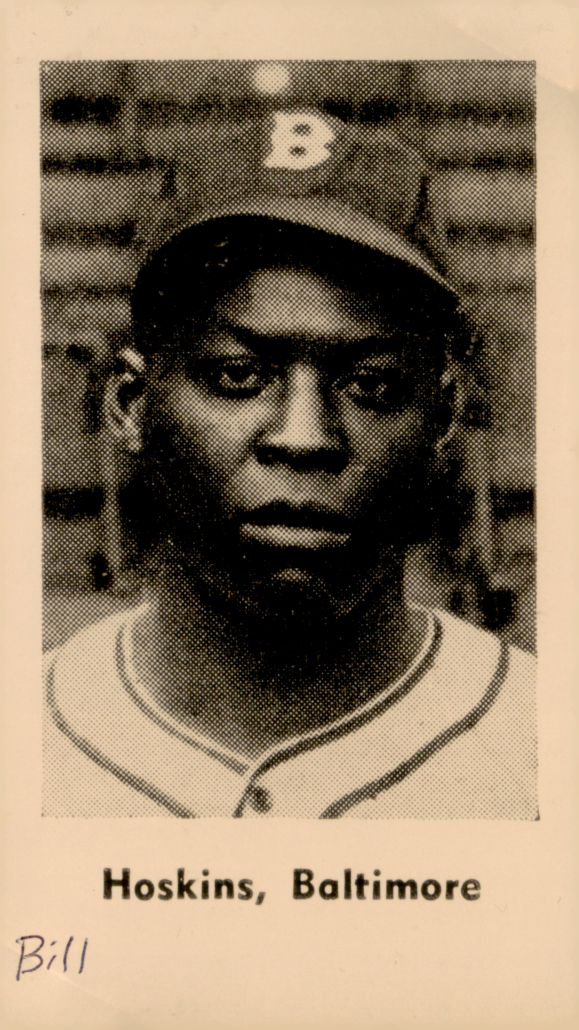

Bill Hoskins

As is the case with so many Negro League ballplayers who were born before the twentieth century or just after it began, details of William Hoskins’ birth and early years are wanting. His draft registration card, issued in 1940, offers as much clarity as is available about his origins, including his reported birth on March 14, 1914, in Tallahatchie County in north central Mississippi.1

As is the case with so many Negro League ballplayers who were born before the twentieth century or just after it began, details of William Hoskins’ birth and early years are wanting. His draft registration card, issued in 1940, offers as much clarity as is available about his origins, including his reported birth on March 14, 1914, in Tallahatchie County in north central Mississippi.1

In 1940 when he registered for the draft, Hoskins was well into his tour with the Baltimore Elite Giants, but the address on the registration card is listed as 749 Bey Street in Memphis, Tennessee. The residence could be explained by Hoskins’ time with the Memphis Red Sox before he joined Baltimore. His wife is listed on the registration card, but only as Mrs. William Charles Hoskins; no first or maiden name is identified. It is possible that he married while in Tennessee and the address is his wife’s family home. Penciled in on the registration card are two additional addresses, one at 31 Rutland Avenue, Baltimore, probably Hoskins’ residence while playing for the Elite Giants. Scribbled above the Bey Street address is 144 E. Main Street in Charleston, Mississippi, the county seat of Tallahatchie County.

The Tallahatchie connection helps refine a search for records that offer further insight on Hoskins’ origins. A 1920 Census record identifies a 6-year-old William Hoskins living with his family in Quitman County, Mississippi, not far from Charleston in neighboring Tallahatchie County.2 This connection is further substantiated by newspaper reports in the mid-1930s identifying fledgling ballplayer Hoskins as a Charleston resident making his way into the baseball world.3

In 1936, at the age of 23, Bill Hoskins’ initiation into Black professional baseball surfaced in newspaper stories placing him that season with the Claybrook Tigers4 and the Cincinnati Tigers.5 A common denominator for those teams was Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe, whom John Claybrook, owner of the Claybrook Tigers (based across the Mississippi River from Memphis in Arkansas), hired as player-manager. Radcliffe noted in his autobiography that Claybrook enticed him to play for the Tigers after seeing him in action for Bismarck the year before.6 After a time with Claybrook, Radcliffe jumped to the Cincinnati Tigers before moving on to the Memphis Red Sox, each time in search of a bigger paycheck.7 No records have yet been unearthed of Hoskins on the Cincinnati squad, but the Radcliffe connection may have played a part in his movement among these three clubs.

Hoskins surfaced again in early 1937 when he joined the first of his Negro League teams of which we are certain: the St. Louis Stars (later the Detroit Stars). Hoskins’ arrival in St. Louis was captured by the Birmingham News, noting that at the instigation of Stars manager Dizzy Dismukes, “Hoskins was purchased from Charleston” the prior winter. The Charleston connection speaks to Hoskins’ hometown.8

By the mid-1930s, Dizzy Dismukes’ Negro League playing career was long over, but he remained as a manager. He had managed the Columbus Bluebirds in 1933, a team on which Ted Radcliffe played. The Dismukes/Radcliffe tie may have contributed to Dismukes’ recruiting of Hoskins for the Stars.

The Pittsburgh Courier affirmed Hoskins’ presence on the team in early May,9 but by the end of June, after only a half-dozen recorded games with St. Louis, he was in Detroit. “The Stars will have their latest acquisition Billy Hopkins [sic] in right field,” the Detroit Tribune reported. “Hoskins, a young Mississippian has seen service with the Cincinnati Tigers and St. Louis Stars. He displayed rare hitting ability on the recent road trip of the Stars and as result has been placed fifth in the batting order.”10 It is not known why Hoskins moved teams, but the player he replaced in left field in Detroit, Eli Underwood, hit only .167 that year and Hoskins’ bat was clearly an upgrade.

Hoskins starred against his former team in a five-game series in Detroit in July, swept by the hosts. “Bill Hoskins, the young pumpkin who had been placed in leftfield by the Stars, paced the onslaught on the Mound City pitchers with eight hits in 16 official times at the plate. Yes sir, Mississippi Bill was pounding the ball with a gusto that provoked smiles on the face of owner Jim Titus.”11 If ever a newspaper story captured the essence of Hoskins’ gift to the game – his pure hitting ability – the Detroit Tribune did. This second coming of the Detroit Stars formed in 1937 by Jim Titus, was disbanded later that year, and Hoskins had to find another home in 1938 for his emerging talents.

That home was the Memphis Red Sox, managed by none other than Double Duty Radcliffe. Multiple news stories lauded the formation of a strong squad shaped by the Martin brothers, owners of the team, and helped by Radcliffe’s prior connections, including those with the Cincinnati Tigers. “In the outer garden are the hard-hitting William Hoskins, last year with Detroit,” and Lloyd Davenport, who played for Radcliffe in Cincinnati the year before,12 and Nat Rogers.13 “The Memphis Red Sox will have the strongest outfield in the Negro American League this year,” the Atlanta Daily World declared. Alongside Davenport and Rogers would be “William Hoskins, one of the hardest hitters in baseball from Charleston, Miss.”14 The hype about the 6-foot-2, solidly-built left-handed batter was no doubt informed as much as anything by Hoskins’ 1937 exploits.

But Hoskins’ time with Memphis15 was short; he was pirated along with two other Red Sox by the Buffalo Aces, a short-lived affiliate member of the NNL despite the expressed intent of the Negro American and National Leagues to respect each other’s team contracts. Cumberland Posey in the Pittsburgh Courier wrote, “[Leonard] Henderson, the manager of the Buffalo Club, came to the conclusion that his club needed considerable strengthening if they wished to compete with other clubs of the N.N.L., so he made a trip to Memphis and signed up three players of the Memphis Red Sox of the Negro American League. This violated a verbal agreement between the two Leagues.”16 However, the players were not returned to Memphis because although “the Negro National League have agreed not to touch players of the Negro American League” it has “not received the reciprocal agreement from the N.A.L.”17

Upon Hoskins’ arrival in Buffalo, the Buffalo Evening News wrote, “Buffalo Aces, the first team in history to represent Buffalo in the Negro National League, will open its home season Sunday afternoon at 3 o’clock against the Newark Eagles in Offerman stadium. … Outstanding players in their lineup include … Bill Hoskins, left field, who hit .360 and connected for 32 home runs with the Detroit Stars in 1937 [Seamheads statistics tell a different story for Hoskins that year: 1 home run, 8 RBIs, and a .324 batting average].”18 Clearly though, Henderson did not do enough to shore up Buffalo’s deficiencies; the club collapsed in the first half of the season and another NNL team swooped in. “The Washington Black Senators have been bolstered for their weekend games at Griffith Stadium with the Newark Eagles and Philadelphia Stars by the addition of five new players. Returning from Buffalo, where the Stars19 [sic, Aces] disbanded, Secretary Roy Sparrow had the signed contracts of Jimmy Ford, second baseman; Bang Long, third baseman; “One Shot” Hoskins, outfielder; and pitchers “Doc” Hayeslett and Slim Johnson.”20

The Black Senators did not do much better than Buffalo and compiled a record of 2-20 in 1938, not even finishing the second half of the season. In the two recorded games for the Black Senators, Hoskins did what he did well: hit. He went 5-for-9 with two doubles and a triple. With the Black Senators’ demise, Hoskins opportunistically moved to his fourth team in 1938, less than 50 miles up the road to Baltimore where he began to make a name for himself for nearly a decade as a linchpin in the outfield.

In his first year with Baltimore during the second half of the 1938 season, in 12 games for which box scores are available, Hoskins’ average sagged to .244. He more than made amends in future seasons and the Elite Giants, now firmly entrenched in Baltimore after its nomadic existence beginning in Nashville nearly 20 years before. The Elite Giants had in Hoskins a key piece that helped elevate them to the Negro National League championship a year later. Managed by George Scales, Baltimore finished in third place in 1938, behind the perennial champion Homestead Grays and equally talented Philadelphia.

Hoskins contributed significantly to the success of Baltimore’s championship team in 1939, and continued to in all or parts of nine seasons for the Elite Giants, where he ended his Negro League career, save for a cup of coffee with the Black Yankees in 1946. He was a career left fielder, a constant outfield presence for Baltimore in at least 349 documented games with the team over nearly a decade playing for Tom Wilson.

The road to the 1939 championship was paved by solid play from a range of Baltimore players. Bill Byrd, Wild Bill Wright, Sammy Hughes, Henry Kimbro, Jonas Gaines, Willie Hubert, 17-year-old Roy Campanella, and their teammates played well enough to squeeze into the four-team playoff that marked how the 1939 NNL champion was crowned. And then there was Bill Hoskins. He led the team in batting at .382, drew a walk whenever he could, had an OPS of .961, and was considered a good fielder with plenty of speed.

In the deciding game of the championship against the Grays, Hoskins drove in the first run of the game in the seventh and later scored, accounting for both runs in the 2-0 Elites victory. His performance as described by the Baltimore Afro-American is worth recounting. “In the lucky seventh … [against Grays hurler Roy Partlow], the Elites crashed the scoring column with the winning tallies. Bill Wright, hero of many Elite games throughout the season, doubled to start the Grays’s downfall. Wright romped home with the initial run of the game a few seconds later as Bill Hoskins walloped a single to left. … [After one out] Hoss Walker … beat out a dribble to third, as Spearman threw wide to the bag, pulling Leonard off. Hoskins pulled up at second on the play, then scored as Leroy [sic] Campanella, young Elite catcher, smashed a single through the box.”21

On the heels of their first championship, the Elite Giants began the 1940 season without three of their players: Bill Byrd went to Venezuela and Wild Bill Wright and Tom Glover took their talents to Mexico. The money was better. The Elites traded for George Scales to return as a player (he had gone to the Black Yankees as player-manager in 1939).22 Two new pitchers were signed. The season began well: Baltimore was in first place until the end of June. But a losing streak had them finish second to the Grays at the end of the first half. The second half of the season ended in the same way, with Baltimore trailing the Grays.

At the age of 26, Hoskins hit a stellar .343 and had an OPS of .996. With Wright in Mexico, George Scales filled in at right and the outfield tandem of Hoskins, Kimbro, and Scales managed batting averages of .343, .260, and .352 respectively. Baltimore’s season might have been summed up by its late July series with the Philadelphia Stars. The Elites swept a doubleheader on a Saturday on the Stars’ home ground but lost to them in Oriole Park the next day, 6-5 in 10 innings, the kind of game Baltimore needed to win to keep pace with the Grays. Hoskins did his best, though, going 3-for-5 and “in the fifth, hit a homer into the rightfield bleachers to score Hughes and Tom Butts ahead of him.”23

In 1941 Baltimore overhauled its team significantly via two trades with the Black Yankees. Baltimore sent Bill Perkins, Harry Kimbro, Bud Barbee, Red Moore, Tom Parker, and Everett Marshall to New York, receiving Charlie Biot, Robert Clarke, Roy Williams, Henry Spearman, and Johnny Washington. The rebuild did not hurt the Elites; in fact, they were only 2½ games behind Homestead over a full season’s play. Wrote Bob Luke, “The Elites kept up the pace [in the first half, behind the Grays] by winning six out of seven behind the heavy hitting of Hoskins, Homer “Goose” Curry, and Charlie Biot. Unfortunately … the Grays played even better, taking first place in the first-half race.24 Meanwhile, the Cubans got hot and won the second half, falling to Homestead in the championship round.”25

The 1941 season was very good for Hoskins: He garnered the fourth-highest number of votes among outfielders and was selected to play in his only East-West All-Star Classic. Hoskins contributed to the East’s 8-3 shellacking of their West opponents, driving in a run in the East’s six-run fourth inning. Hoskins, batting third, went 1-for-5 and was one of three Elite Giants who played that day,26 alongside Roy Campanella behind the plate and Bill Byrd, who pitched a scoreless ninth to nail down the victory.27

The situation for the Elite Giants leading into 1942 could not have been better framed than what Bob Luke wrote in his history of the team: “The Elites had acquitted themselves well during the two years of disruption to their roster brought about by trades and defections of star players to Latin America. They looked for better things in 1942.”28

Thanks to Kimbro’s return from the Black Yankees, the league’s best outfield was reassembled – Hoskins, Wright, and Kimbro. Wright had returned from Mexico as had Sammy Hughes, Andy Porter, and Tom Glover. The team played well in the first half of the season, outperforming the opposition. Somehow, there was no playoff between the first- and second-half champions and Baltimore lost the opportunity to play for a place in the World Series against the NAL’s Monarchs.29 Hoskins again was superb; he could always be relied on to bat over .300 and hit for extra bases and power and did not disappoint with a .314 batting average and 15 extra base hits in 159 at-bats.

In mid-June, when Baltimore was leading the league, the Baltimore Afro-American ran a story with photos of the Elite outfielders, writing that “this trio of fly chasers guard the outer pastures for the Baltimore Elites and rate as one of the best, if not the top-ranking outfield in the National League.”30 In the second half, the Grays built up steam and led Baltimore throughout. The Elites tried to catch up as the season neared an end, and swept the Black Yankees at Bugle Field in a three-game series, punctuated by Hoskins hitting in every game, driving in and scoring runs.31 But the Grays prevented Baltimore’s sweep of a Labor Day doubleheader with Homestead that had been necessary for the Elite Giants to claim the crown.

Entering the 1943 season, Baltimore had had a good run in the NNL – above .500 in its first year in the league in 1938, a championship in 1939 and successive second-place finishes to rival Homestead the following three years. But 1943 was different, and in league play the team finished a distant fifth despite the acquisition of solid left-handers Bill Burns and James Carter. It did not help that Baltimore lost Campanella, Wright, and Butts to Mexico. Scales replaced Felton Snow as manager and despite Tom Wilson shoring up the club with players from his Nashville Cubs, the team struggled out of the gate and never recovered.32

Hoskins registered for the draft in 1940 and, although he did not serve in the military, he and fellow Elite Giants worked locally on defense jobs during the war. The Afro-American noted in January: “Jim Kimbro, Bill Harvey, Bill Hoskins, and Tom Glover, all members of the Elite Giants, are working in a Baltimore steel plant.”33 In March the newspaper wrote, “In Baltimore, four key players of the Baltimore Elite Giants have threatened to stay on their defense jobs, giving up baseball for the duration. The men, all of whom are employed in the city, are Bill Hoskins and Henry Kimbro, regular outfielders, and two of last season’s pitching mainstays, lefthanders Tom Glover and Bill Harvey.”34 This may have been a ploy by the players to leverage better pay from owner Wilson. Eventually, the players quit their jobs in time for the regular season.35 The May 29 Afro-American reported that “Jim Kimbro, Bill Hoskins, and rookie, Biggie Williams … are the outfielders.”36 Hoskins played in fewer games that season than most of his Baltimore teammates; his 36 appearances represented half of the Elite Giants’ regular-season total of 69. Early in the season the Afro-American noted his absence due to illness: “Bill Hoskins, Elites outfielder, was in Baltimore ill, necessitating the use of Byrd and Bill Harvey, pitchers, as an outfielder at alternate turns.”37 Whether one or more ailments that year contributed significantly to Hoskins’ reduced play and his career-low batting average of .275 is uncertain.

In 1944 Hoskins had one of his best years, albeit for a fourth-place team – .388 batting, a .441 on-base percentage, .621 slugging percentage, and a mammoth 1.062 OPS. The core of the team remained from previous years and Hoskins played alongside Kimbro, Snow, Campanella, Butts, and Scales in a fearsome lineup that was otherwise let down by the rotation of Byrd, Gaines, Glover, and Harvey, who could not match their previous accomplishments. Box scores routinely noted Hoskins’ ongoing contributions. A game in June in Detroit against the Cubans delighted the locals. “Bill Hoskins, playing before his former hometown fans, shoved the Elites to the front in the first inning when he pelted one of Dave Barnhill’s fast balls high into the right field tier [of Briggs Stadium].”38 Against the Cubans later in the season, the Afro-American wrote, “Bill Hoskins, Elites leftfielder, poled a homer in the eighth with two on.”39

In 1945 the Elites finished no better than the middle of the pack. Hoskins did not match his 1944 numbers, but they were not to be sneezed at: He batted .315 over .300 continuing to show power and speed with 19 extra-base hits. One bright spot for the team was its veteran presence – Hoskins, Kimbro, and Wright continued to patrol the outfield; Campanella, although only 23, was himself a veteran, having played for the team since its Washington Elite Giants edition in 1937; Doc Dennis, Harry Williams, Butts, and Snow in the infield all contributed serviceably. However, the aging pitching staff let the team down with a composite ERA of 4.72; the team simply could not compete against the Grays and Eagles and came in third. Hoskins did his best, as captured by a June storyline in the Baltimore Afro-American: “The big bat of Bill Hoskins and the trusty right arm of Archie Hinton, rookie pitcher, combined to set the New York Cubans back on their heels here last Tuesday night, 9-2. Hoskins connected for a home run and a triple to account for five runs.”40

The 1946 season marked the beginning of a youth movement for Baltimore. Three rookies drew the attention of the team, but for the time being Hoskins was still in the plans. The Afro-American noted, “The whole squad, with the exception of Bill Hoskins who is expected to report from Panama this weekend, and Jonas Gaines … are gradually rounding into shape.”41 The reference to Panama implied Winter League play for Hoskins in Central America, but no details so far have been found. The season then began for Hoskins as most others did; in May, in a rain-shortened game against the Grays in Washington. Hoskins produced, hitting a 410-foot run-scoring triple in cavernous Griffith Stadium to ensure a Baltimore victory.42

Hoskins’ long run with Baltimore came to an end in June 1946. “The Baltimore Elite Giants on Monday announced a deal which sent Bill Hoskins, veteran outfielder, to the New York Black Yankees in exchange for Johnny Hayes, a catcher who formerly played with the Newark Eagles. Hoskins, however, had not reported to the Yankees late Monday night, there being a strong hint that he could not reach salary terms with the Harlemites.”43 The Black Yankees and Hoskins did reach a deal and Hoskins’ career continued in New York for the remainder of the 1946 season. Records show Hoskins playing in nine games with the Black Yankees, having already played in 44 that season with Baltimore. His batting average for the combined season was .287, the lowest of his career except for his .275 average in 1943. It was his lowest OPS (.762), well under his career average of .906, due primarily to recording no home runs.

In early 1947, Afro-American columnist Sam Lacy reported that the “[r]ebuilding Balto. Elites are hanging out the names of Bill Hoskins … Andy Porter [and others] as trade bait.”44 This came after the Elites’ trade of Hoskins to the Black Yankees a year before; perhaps Hoskins had returned to Baltimore to offer his talents in his adopted hometown, only for the Elites to prefer the continuing youth movement. There were no takers. Two months later Lacy wrote, “Bill Hoskins, veteran Elite outfielder, reports that he’s been offered $500 per month by the Mexican League.”45 His obituary in 1968 also suggested he played for the Mexico City Reds for several years, but this has not yet been substantiated.46

Hoskins continued to play baseball, and in 1948 and 1949 was with the Richmond Giants, a Negro American Association team. The NAA was formed to complement the still-existing NAL and maintain Black baseball in some form in the face of slow integration of the American and National Leagues. Hoskins was only 32, but his prospects for playing in either the White majors or their minor-league systems was dim. Richmond had to suffice. Multiple reports in 1948 in the Richmond Times-Dispatch affirmed that he could still hit.47 However, 1949 was the beginning of the end. In April the paper wrote that the “biggest disappointment to date has been the hitting of Big Bill Hoskins, the team’s top batter with .339 and 27 homeruns last season.” The Giants folded at the end of the 1949 season and Hoskins’ further play in organized baseball of any form has not yet been substantiated.48

Along with his Negro League play, Hoskins also participated in the California Winter League. He first appeared for the Philadelphia Royal Giants, in the winter of 1939-1940 after Baltimore’s championship season. The Royal Giants won the league going away and Hoskins, with a .303 batting average in nine games, teamed with fellow Elite Giants Bill Wright, Jim West, Bill Harvey, and Tom Glover, as well as Mule Suttles, Pepper Bassett, and Jake Dunn, to win the title. Although a squad under the name of the Baltimore Elite Giants, managed by Felton Snow, participated in the League, Hoskins did not join it.49

In 1945 and 1946, Hoskins returned to the California Winter League, this time with the Kansas City Royals, managed by Chet Brewer. Hoskins reprised his time out west with Elite Giants teammates Bill Wright and Andy Porter, but Brewer, Satchel Paige, and a young shortstop by the name of Jackie Robinson were the more prominent names on the Royals. Hoskins still had it, though, and led the league in batting (.444) and home runs (2).50

In 1947 there was no Winter League per se, but two teams led by Bob Feller and Satchel Paige more than made up for it by a series of exhibitions that autumn. Hoskins played on the Royals again alongside Piper Davis, Jesse Williams, and Paige. Feller’s All-Stars. Who included Feller, Peanuts Lowrey, Bob Lemon, Roy Partee, and Cliff Mapes, bested the Royals in their head-to-head play, but KC redeemed itself by defeating another team, led by Ewell Blackwell.51

Having played in Baltimore for nearly a decade, Hoskins’ roots in the city were well established. The 1950 Census had him in Baltimore working for a department store as a warehouseman. Sam Lacey, in a 1958 column in the Baltimore Afro-American, confirmed this, writing, “Bill Hoskins, ex-Elite outfielder, is a department store employee in Baltimore.”52 The Census does not refer to his wife or any offspring, nor does his obituary in the Afro-American 10 years later.

Hoskins died on February 9, 1968, in Baltimore. According to the Afro-American, Hoskins “had a history of heart difficulty.”53

With more research about Negro League taking place, players like Bill Hoskins begin to get their due. Hoskins was not a Hall of Famer, but he was a solid outfielder who could hit for both average and power. He might have won a roster spot on an American or National League team of the day, and who knows, more fans would have known about him and celebrated his game.

Acknowledgments

All statistics are from Seamheads and Baseball Reference, unless otherwise noted.

Special thanks to Rich Bogovich for his insights into Big Bill.

Notes

1 William C. Hoskins 1940 draft registration card.

2 1920 Federal Census.

3 One additional layer meriting future research relates to Hoskins’ relationship to Ben and Dave Hoskins – Cousins of his – who also played baseball, including, in the case of Dave, time in both the Negro Leagues and then the Cleveland Indians in the 1950s.

4 “St. Louis Stars’ Notes,” St. Louis Argus, April 30, 1937: 6.

5 “Chicago-Star Series Sharpened by Rivalry,” Detroit Tribune, June 26, 1937: 3.

6 Kyle P. McNary, Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe, 36 Years of Pitching and Catching in Baseball’s Negro Leagues (Minneapolis: McNary Publishing, 1994), 129-131.

7 McNary, 138-140.

8 Untitled, Birmingham News, May 14, 1937: 8.

9 “St. Louis Stars Ready for Season,” Pittsburgh Courier, May 8, 1937: 17.

10 “Chicago-Stars Series Sharpened by Rivalry.”

11 “Visitors Are Shoddy with Play Afield: Pitching and Batting of St. Louis Club Also Weak,” Detroit Tribune, July 10, 1937: 6.

12 “Memphis to Strengthen Out Garden: Fastest Fly Chaser in League Is What the Margins Want,” Chicago Defender, March 5, 1938: 10.

13 “Memphis Gets in Shape for N.N. Leaguers,” Chicago Defender, March 26, 1938: 9.

14 Memphis Red Sox Line Up for Practice,” Atlanta Daily World, March 4, 1938: 5.

15 When Hoskins left Memphis, Cowan Hyde replaced him to team up with Davenport and Rogers in the outfield for a team that would win the 1938 Negro American League over strong competition from Kansas City, Chicago, and Atlanta.

16 Cum Posey, “Posey’s Points,” Pittsburgh Courier, May 7, 1938: 16.

17 “Posey’s Points.”

18 “Negro Nine to Open,” Buffalo Evening News, May 26, 1938: 12.

19 Did the Stars reference mean there was a connection between the Detroit team’s demise the year before and the formation of a new Negro League team in Buffalo in 1938?

20 “D.C. Colored ‘9’ Adds 5 Players,” Washington Times, June 30, 1938: 32.

21 “Elite Giants Win National League Championship: Baltimore Nine Tops Grays in Series, 10-5 and 2-0 to Gain Rupert Trophy; Gaines Hurls Shutout Over Homestead Team,” Baltimore Afro-American, September 30, 1939: 21.

22 George Scales – Society for American Baseball Research (sabr.org).

23 “Elites Jolted by Philly Stars in 10 Innings, 6-5,” Baltimore Afro-American, July 27, 1940: 21.

24 Bob Luke, The Baltimore Elite Giants: Sport and Society in the Age of Negro League Baseball (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009), 65.

25 New York Cubans – 1941 Season Recap – RetroSeasons.com.

26 “Three Elites Named to Play on East Team,” Baltimore Afro-American, July 26, 1941: 21.

27 Larry Lester, Black Baseball’s National Showcase: The East-West All-Star Game, 1933-1953 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2001), 152-155.

28 Luke, 67.

29 Luke, 72-73.

30 “3 Reasons Why Elites Hold Loop Lead,” Baltimore Afro-American, June 13, 1942: 22.

31 “Gain on Grays in Hot Race,” Baltimore Afro-American, September 5, 1942: 23.

32 Luke, 81-83.

33 Art Carter, “From the Bench: Philly Stars, Newark Eagles Are Hit Hardest by the Draft,” Baltimore Afro-American, January 30, 1943: 18.

34 “Baseball Bits,” Baltimore Afro-American, March 27, 1943: 23.

35 No information is available about the terms of the players’ employment in the defense industry and their eligibility to be called up. Hoskins was 28 in 1943.

36 “Mayor to Throw Out Ball as Elites Play Grays on Sunday,” Baltimore Afro-American, May 29, 1943: 23.

37 Art Carter, “Gibson Hits 2 Homers; Grays Sweep Philly Series: Eagles, St. Louis Divide Cubans Take Twin Win from Elites to Stay Unbeaten,” Baltimore Afro-American, May 29, 1943: 23.

38 Russ Cowans, “26,000 See Elites, N.Y. Cubans Split,” Baltimore Afro-American, June 17, 1944: 18.

39 “Elites Top Cubans Twice in Series, Drop Exhibition,” Baltimore Afro-American, August 26, 1944: 18.

40 “Hoskins Bat Beats Cubans,” Baltimore Afro-American, June 2, 1945: 23.

41 “2 Puerto Ricans Impress Elites,” Baltimore Afro-American, April 13, 1946: 18.

42 “Hoskins’s Triple Spoils Grays’ Bow,” Baltimore Afro-American, May 18, 1946: 15.

43 “Elites Trade Hoskins, Farm Out Infielder,” Baltimore Afro-American, June 29, 1946: 19.

44 Sam Lacy, “A to Z Sports,” Baltimore Afro-American, February 1, 1947: 17.

45 Sam Lacy, “From A to Z,” Baltimore Afro-American, March 29, 1947: 13.

46 Neither Baseballreference.com nor Pedro Tetro Cisneros’s excellent compilation of statistics from the Mexican League in The Mexican League / La Liga Mexicana: Comprehensive Player Statistics, 1937-2001 bilingual edition records Hoskins’ presence in the league.

47 The newspaper diligently covered the Giants, and Hoskins’ power was often featured. See Richmond Times-Dispatch, May 10, June 13, July 19, and August 30, 1948.

48 “Giants Ready Before Long, Says Manager,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, April 15, 1949: 33.

49 William F. McNeil, The California Winter League: America’s First Integrated Professional Baseball League (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2002), 201-205. Over the next several years, teams named the Baltimore Colored or Elite Giants played in the league, but these were all-star squads of Negro League players and not the Baltimore team itself.

50 McNeil, 223-232.

51 McNeil, 232-235.

52 Sam Lacy, “A to Z Sports,” Baltimore Afro-American, August 23, 1958: 13.

53 “Ex-Elite Bill Hoskins Is Buried,” Baltimore Afro-American, February 20, 1968: 14.

Full Name

William Charles Hoskins

Born

March 14, 1914 at Tallahatchie County, MS (USA)

Died

February 9, 1968 at Baltimore, MD (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.