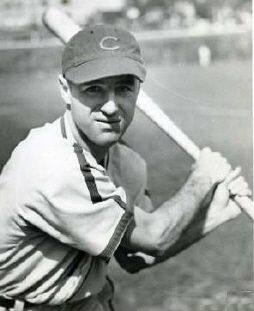

Billy Jurges

Billy Jurges, a star shortstop for the Chicago Cubs (1931-1938, 1946-1947) and the New York Giants (1939-1945), played a part in Babe Ruth’s called home run during the 1932 World Series, and perhaps provided some of the inspiration behind Bernard Malamud’s novel The Natural and the movie by the same name. He helped prompt the use of batting helmets and the institution of nets on foul poles, and as manager of the Red Sox, presided over the racial integration of the last segregated team in major-league baseball. Batting and throwing right-handed, he cast a slender shadow, standing 5-feet-11 and weighing 175 pounds.

Billy Jurges, a star shortstop for the Chicago Cubs (1931-1938, 1946-1947) and the New York Giants (1939-1945), played a part in Babe Ruth’s called home run during the 1932 World Series, and perhaps provided some of the inspiration behind Bernard Malamud’s novel The Natural and the movie by the same name. He helped prompt the use of batting helmets and the institution of nets on foul poles, and as manager of the Red Sox, presided over the racial integration of the last segregated team in major-league baseball. Batting and throwing right-handed, he cast a slender shadow, standing 5-feet-11 and weighing 175 pounds.

William Frederick Jurges was born May 8, 1908, in the Bronx, New York, the son of Frederick Jurges, a shipping clerk, and Anna Horstman Jurges. The couple had four other children. When Billy was 2, his family moved to a middle-class neighborhood in Brooklyn, where he later attended Richmond Hill High School in Queens. He delivered groceries with a horse and cart, as he learned baseball on the sandlots. His father became a floor manager at a bank, and Billy got a job there as a messenger. He continued to improve his baseball skills and moved on to semipro ball, developing a reputation as a smooth fielder with a rifle arm.1

In 1927 the Newark Bears signed Billy to play the outfield and sent him to Manchester, New Hampshire, of the New England League. The Blue Sox had three regular outfielders, so Jurges started working out at shortstop. He spent the offseason chopping wood to gain strength, and returned the next season to lead the league in hits and raise his average from .255 to .332. Impressed, Chicago Cubs scout Jack Doyle signed Jurges in 1929, and the Cubs sent him to their Double-A affiliate in Reading, Pennsylvania. Billy quickly made a reputation with his slick fielding, but the Cubs wondered how he would hit major-league pitching. Cubs manager Rogers Hornsby believed fielders could learn their craft with time, but that good hitters were simply born. In 1931 Hornsby gave Billy a chance, playing him in 88 games. The next year, Jurges became the Cubs’ regular shortstop, nudging Woody English to third. Billy also showed that he could hit, raising his rookie average of .201 to .253 his second year.

On July 6, 1932, in Jurges’ first full season as a big leaguer, a scorned showgirl named Violet Popovich Valli interrupted his breakthrough when she tried to kill both herself and the young ballplayer. Early that morning, the pretty brunette singer and showgirl, who had dated Jurges, entered the Hotel Carlos (now the Sheffield House) just a few blocks north of Wrigley Field in Chicago and called Jurges’ room from the front desk.

Her .25-caliber pistol fired three shots, hitting Billy in the little finger of his left hand and in a rib, then ricocheted out his right shoulder. The third hit Valli in her arm and broke her wrist. Dr. John Davis, the Cubs physician, heard the shots from the lobby and found neither seriously hurt. Jurges never pressed charges.

Reportedly receiving advice from her pastor,2 Valli continued to pursue her show-business career, now billed as Violet “What I Did for Love” Valli, the Most Talked-about Girl in Chicago, with a 22-week contract in clubs throughout Chicago.

The shooting incident, along with a similar incident involving Eddie Waitkus in 1947, probably provided Bernard Malamud inspiration for his 1952 novel The Natural, the basis for the classic 1984 baseball movie. It also triggered a chain of events that set the stage for one of the most famous stories in baseball history: Babe Ruth’s supposed called shot in the third game of the 1932 World Series.

When Jurges returned to the field at the end of July, he found many changes on the Cubs. Charlie Grimm had replaced Hornsby as manager, and Mark Koenig had joined the team to play shortstop. Koenig, a member of the 1927 Murderers’ Row Yankees, restarted his career when the Cubs acquired him as insurance from the San Francisco Missions of the Pacific Coast League. He batted .353 in 33 games, and helped lead the Cubs to the World Series against the Yankees.

A full share of the World Series money required a unanimous vote of the players. Jurges and teammate Billy Herman placed two dissenting votes, resulting in Koenig’s receiving only half a share. The team also voted to exclude Hornsby completely, though he had managed the team the first two-thirds of the season. “The Cubs’ stinginess fired the Yankees to new heights,” penned Shirley Povich of the Washington Post.3 Koenig had friends on the Yankees, chief among them Babe Ruth. Throughout the first two Series games in New York, Ruth led the Yanks in taunts of the Cubs, calling them cheapskates. The Cubs gave it right back, calling Ruth big-belly and balloon-head.4

The Yankees won the first two games, and the Series moved to Chicago’s Wrigley Field. The taunting resumed and intensified, with the ballpark full of fans joining the commotion. Ruth hit a three-run homer in the first inning, then came up for his third at-bat in the fifth inning, with the bases empty and the score tied, 4-4. The fans tossed lemons that rolled at his feet as Ruth faced the Cubs dugout from the left-handed side of the plate. The jeers continued, and the Babe pointed at the dugout after each pitch, as well as at starting pitcher Charlie Root. He called the Cubs “cheapskates,” remembering their votes on the Series cash, and said he needed only one good pitch. Finally, with the count 2-2, he pointed to center field or to the pitcher – no one knows for sure – then hit the next pitch for one of the longest and prettiest home runs in Wrigley Field history.5 Lou Gehrig hit the next pitch deep into the right-field stands. The Yankees held on to win 7-5, and swept the Series the next day with a 13-6 victory.

Less than a year after being shot in the hotel, Billy married Mary Huyette on June 28, 1933, in Birdsboro, Pennsylvania. Later that day they drove to Philadelphia, and Jurges belted six hits in a doubleheader against the Phillies

Now restored to health, Jurges joined the Cubs’ lineup to stay. Hornsby’s glowing assessment early in the 1932 season became prophetic for the rest of Billy’s career: “He covers more ground, makes more stops, makes faster, more accurate throws from any position than any shortstop you can name.”6

The street kid from Brooklyn teamed with an Indiana farm boy, future Hall of Famer Billy Herman, at second to form the double-play combo that led Cubs teams to three World Series appearances in the 1930s. This middle infield made work easier for managers and pitchers alike, receiving a big part of the credit when the starting pitchers completed 10 games in a row in 1935. In the World Series that year, Jurges set a record for putouts by a shortstop in a six-game series, with 16. Jurges was selected for the National League All-Star team in 1937, 1939, and 1940. His 1941 Play Ball baseball card called him “the most valuable shortstop in the National League.”7

Jurges came close to managing the Cubs in 1938 when owner P.K. Wrigley offered him the job. But Billy replied, “Mr. Wrigley, Gabby Hartnett has played for you for nearly 20 years. I think he should be your manager.” Hartnett got the job, then in his first trade, sent Jurges to the Giants.8

One day in Brooklyn, Jurges picked Frenchy Bordagaray off second base when he was supposedly standing on the bag. After hitting a double, Frenchy was talking to Billy at second while Brooklyn manager Casey Stengel argued a call with the home-plate umpire. Before Stengel got back to the dugout the inning was over; Bordagaray had been tagged out. Frenchy explained later, “I was tapping my foot as I talked with Jurges, and he must have got me between taps.”9

Considered a gentleman off the field, Jurges developed a fiery reputation as one of the most volatile competitors in the game. Leo Durocher named Jurges his shortstop when asked to pick players for an all-star team based on “the way they might handle their fists in case of a fight.” In an era when tough play was the norm and ejections rare, Billy got the thumb at least once each season in 12 out of 15 years, from 1932 through 1944. He led the National League with three ejections in 1936.10

Second base became a war zone for runners hoping to gain access past the feisty Jurges. “A lot of guys would hate you. Really hate you,” Billy said. “It was part of baseball.”11 After a couple of rough plays from both sides in a game against the Dodgers in 1932, Jurges wound up in a fight with Neal Finn. In the spirit of the times, they shook hands after they were both ejected.

In 1933, Billy threw a ball into the Phillies dugout, scattering their players, as they protested his aggressive play. He grabbed another ball and fired a second time, bringing both teams on the field in a near riot, until interrupted by umpire George Magerkurth, a 6-foot-3, 240-pound former boxer. Surprisingly, Jurges was neither ejected nor fined.

Billy stepped on Cookie Lavagetto’s hand in 1935 and drew a three-day suspension and a fine. Ironically, Lavagetto later named Jurges as one of his coaches, and the two roomed together when Lavagetto managed the Senators in the 1950s.

In 1935 Jurges got into a fight on his own bench with rookie backup catcher Walter “Tarzan” Stephenson, from North Carolina. Jurges claimed his grandfather had rounded up a group of Confederate soldiers, including Stephenson’s grandfather, using only a cornstalk. Manager Charlie Grimm broke up the dispute, fearing Jurges might hurt his hands. The Cubs sent Stephenson to the minors to eliminate the friction, but had to recall him immediately when starting catcher Hartnett broke an ankle.

The rough play carried over to the 1935 World Series, with the ejection of Cubs manager Charlie Grimm over a play at second base – only the second time a manager had been ejected in a World Series game. Grimm drew a $200 fine, as did Jurges and infielders Billy Herman and Woody English, as well as umpire George Moriarty.

Jurges’ biggest ruckus took place on July 15, 1939, with Jurges playing in his first year with the Giants. With the Giants leading the Reds 4-3 in the eighth inning and a runner on first, Harry Craft hit a line drive into the stands down the left-field line. Home-plate umpire Lee Ballafant called the shot fair – a home run, but the whole Giants team protested. First-base umpire George Magerkurth came to Ballafant’s support and found himself face-to-face with an angry Billy Jurges. These two contestants, neither involved directly in the play or the call, disputed the hardest and received the most severe recriminations. They faced off, each loosely sloshing tobacco juice. Billy let some wetness fly in the ump’s direction, then took a blow from Magerkurth and returned one of his own. The terrific row that ensued left three Giants, including Jurges, expelled. “I’ve knocked out a few pitchers in my day,” said Craft, “but that was the first time I ever knocked out a ballclub.”12 Reds starting pitcher Johnny Vander Meer later said, “Jurges was right. The ball was foul by 15 feet.”13

National League President Ford Frick assessed matching 10-game suspensions and $150 fines to both Jurges and Magerkurth. This swift, strong action suprised many, since umpires very rarely faced such discipline. Jurges received relatively mild punishment for such a major violation. In a subsequent action with far-reaching impact on the history of baseball, Frick ordered two-foot-wide screens installed inside all foul poles to help prevent such future arguments.14

The New York chapter of the Baseball Writers’ Association of America remembered the incident early in 1942. Amid serious speeches about baseball played during wartime, the scribes included some light moments satirizing recent on-field events. “One of the funniest skits in the history of the show,” according to J.G. Taylor Spink, editor of The Sporting News, involved “Jurges Lotion,” portraying Jurges as the developer of “a fine soothing lotion” which umpire Magerkurth agreed “surpassed all expectorations.”15

Billy matched his feisty play on the field with hilarious antics off the field. Chicago’s combo of Jurges, English, and Augie Galan became labeled the Katzenjammer Kids, after the impish comic-strip youngsters. One time, the Cubs had to get off their train because of a power failure. In the dark, the three managed to get a freight car wheel into pitcher Lon Warneke’s berth. Warneke never slept that night. Another time they set fire to a wastebasket in trainer Andy Lotshaw’s hotel room. The fire damaged a chair and an end table, but the “Kids” obligingly paid the $56 damage.

At the Polo Grounds on June 23, 1940, Jurges was struck in the head, just behind his left ear, by a pitch thrown by Bucky Walters of the Reds. Although carried to the clubhouse on a stretcher, Billy did not appear to be seriously hurt. Examination at a New York hospital later revealed that he had suffered a concussion.16

Jurges experienced frequent dizzy spells the rest of the 1940 season. While he played in Cuba in spring training the next March, his fingertips and ears went numb. He returned to New York for further treatment, fearing he might not play that season. He took the advice in an inspiring letter from Lou Gehrig and proceeded to the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota for treatment from Dr. Bayard Horton. Feeling much better, Billy returned to the Giants and managed to play 134 games at shortstop that season, batting .293 in more than 500 plate appearances. Yet the dizziness continued, as did the trips to the Mayo Clinic.

Billy’s beaning raised serious consideration of the requirement of some form of protective headgear for batters. Many players resisted the idea, saying they would feel silly and would be hindered by the extraneous equipment. That summer National League President Ford Frick began meetings with medical experts and team owners, setting into motion the process that eventually led to the compulsory use of batting helmets.17

In 1941 Jurges strung together nine consecutive hits, one short of the existing record. He ended this streak with a strikeout, then collected another four hits in a row. He led the National League in hitting in early August with a .368 average, but injured his left shoulder sliding into home. He finished that season at .290 but became an opposite-field hitter, no longer able to get his bat around quickly. His hitting never rivaled his stellar fielding, yet he finished with a respectable .258 career batting average.18

Billy completed his playing days back with the Cubs in 1946 and 1947 and coached for them in 1947 and 1948. He rejected an offer to coach the Cincinati Reds in 1949 under manager Bucky Walters, ironically the former pitcher who had beaned him in 1940. He accepted instead a position in promotional work with A.G. Spalding and Brothers. “I’d like to build a house and settle down,” he said. “Mrs. Jurges had been after me for five years to quit the road and ‘start living like a human being.’”19

Jurges soon returned to baseball, coaching in the minor leagues and managing the Class B Cedar Rapids (Iowa) Indians in the Illinois-Indiana-Iowa League in 1950, and the Hagerstown (Maryland) Braves in the Piedmont League in 1953. In 1955, Billy had re-entered the business world and was working at a better paying job for a manufacturing company in the Washington area, when manager Charlie Dressen of the Senators hired him as a coach, following the recommendation of another of his coaches, Cookie Lavagetto, one of Billy’s early antagonists.

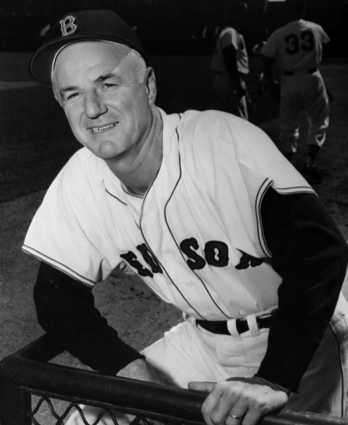

In 1959, Jurges’ big opportunity to fulfill his longtime dream of managing in the major leagues came as a surprise to him and to everyone else, when he was summoned to take over the Boston Red Sox from Mike “Pinky” Higgins on July 3. He had never worked in the Boston organization, nor met owner Tom Yawkey. He hesitated in passing on the good news to his father, who at the age of 86 was confined to a wheelchair. “Break it to him easy. I don’t want him to get too much excitement.” He postponed his trip to join the team and bypassed the All-Star Game to visit first with his dad.20

In 1959, Jurges’ big opportunity to fulfill his longtime dream of managing in the major leagues came as a surprise to him and to everyone else, when he was summoned to take over the Boston Red Sox from Mike “Pinky” Higgins on July 3. He had never worked in the Boston organization, nor met owner Tom Yawkey. He hesitated in passing on the good news to his father, who at the age of 86 was confined to a wheelchair. “Break it to him easy. I don’t want him to get too much excitement.” He postponed his trip to join the team and bypassed the All-Star Game to visit first with his dad.20

Jurges began the job in Boston expecting the players to reflect his competitiveness and hustle. Though most managers ruled from the bench, he planned to coach at third base, saying, “I don’t think I’d be able to sit still enough. I’d wear out my britches on the bench.”21

Less than three weeks into his term, Billy was part of baseball history again. On July 21, Pumpsie Green became the first African-American to play for the Red Sox, thereby completing the integration of the major leagues, more than 12 years after Jackie Robinson’s debut.

Jurges coasted through the integration controversy as the team performed well the rest of the season. He inherited a paltry 31-42 won-loss record (.425 percentage), and the Jurges-led Red Sox went 44-36 (.550 percentage) the rest of the season. The team also won the season series with the archrival Yankees, for the first time in 11 years.

Despite Billy’s early success, rumors of unrest began to arise among the players, who resisted his attempts to instill discipline and hustle. An unnamed Red Sox player remembers Jurges “would put on these rah-rah speeches in the clubhouse, and you had to figure he was kidding.”22

Very sensitive to criticism, Jurges became particularly perturbed when baseball writers printed a player interview hinting that some players were simply going through the motions to finish the season. The rookie manager addressed the team in front of the writers, embarrassing both sides, writers, and players, causing both to question the skipper’s managerial savvy. The Red Sox finished the 1959 season in fifth place, out of the money for only the second time since 1945.

Jurges survived the awkward situation for the time being, but preparing for the1960 season presented major challenges. The team clearly showed its age. Former MVP and RBI leader Jackie Jensen and veteran catcher Sammy White made late announcements of their retirements.23 Sources did not expect Ted Williams to play more than 100 games, as the aging superstar was coming off the worst season in his career.

Looking back on his time in Boston, Jurges said, “All my players on the Red Sox were finishing up their careers, and there was not much I could do there.”24 He wanted at least five more top-level players to become a strong contender. Expressing his frustration, he later stated, “I’d have to be with a front-runner. I am not too good with losers. It’s not in me.”25

Jurges continued to demand hustle and commitment. He conducted special instructional sessions – dubbed Jurges Tech – for the younger, inexperienced players.26 He gave Ted Williams a new role as special batting instructor, leading some to think the former superstar might soon move into managing himself. Billy invited his old infield partner Billy Herman to coach third base, while Jurges took charge in the dugout.

Seeking more right-handed power, Jurges and general manager Bucky Harris traded pitcher Frank Baumann to the White Sox for first-sacker Ron Jackson, according to Boston writer Hy Hurwitz one of the worst trades made by the Red Sox.27 Baumann won the American League ERA crown in 1960, while Jackson proved a major disappointment.

The juggling and maneuvering did not bring good results. Jurges received a “vote of confidence” from owner Tom Yawkey and Harris at the end of May, yet the team slumped well under .500. Criticism of Billy’s leadership flowed from every side. By this point he could hardly manage a smile, much less a struggling ballclub.

On June 8 the team announced that coach Del Baker had replaced Jurges on an “interim basis for an undetermined period.” The Red Sox acted after the team physician, Dr. Ralph McCarthy, and a Boston internist, Dr. Richard Wright, examined Jurges and concluded that he was “completely exhausted from a fruitless task.”28 Jurges clearly appeared tense and nervous, saying reportedly, “No job is worth it if it’s going to ruin your health.”29 The team statement said the doctors had concluded that his health was in danger “due to the continued poor showing of the club in the won and lost column.”30

Billy regarded his hiatus as an extended vacation, no more than three weeks or so. He sent a special-delivery letter to Yawkey listing the conditions under which he would return as manager. On June 12 Yawkey announced that Higgins would return as Red Sox manager, officially ending Jurges’ term less than a year after it started.

The Higgins appointment stunned Jurges. He never considered his health condition that severe. He blamed his “illness” on hotel food. “I had dinner in a hotel restaurant – Hungarian goulash it was – with my wife, Mary. Before I had finished I said, ‘This goulash makes me feel sick.’ And when I got to the ball park I was sick. … That’s the way it happened.”31

Bob Burnes, sports editor of the St. Louis Globe Democrat, labeled the bizarre chain of events “the most muddled managerial firing” of the season. The Red Sox “gave Bill Jurges two votes of confidence, then gave him a leave of absence. They fired him and complicated the whole thing by rehiring the man Jurges had replaced, Mike Higgins.”32

Just weeks after leaving the Red Sox, Billy joined the Orioles as a scout “at large,” to prepare for the offseason trading period. He found other big league work early the next season with the brand-new New York Mets, as an advance scout prior to their player draft.

Jurges soon moved to the other new team of 1962, and became a scouting supervisor with the Houston Colt .45’s. Just before the 1969 season, after living in the Washington, D.C., area for 16 years, he rejoined his “local” club, the new Washington Senators. He returned finally to the Cubs to finish his active career as a scout from 1979 to 1982.

While scouting, Jurges continued to work as an instructor, particularly during spring training, well past age 70. Jurges worked for a dozen big league franchises and influenced the careers of many ballplayers, including Ray Boone, Ken Boyer, Rocky Bridges, Sonny Jackson, Harmon Killebrew, Johnny Logan, Eddie Mathews, Joe Morgan, and Jim Sundberg. He finally stopped when his wife’s health deteriorated, and he chose to spend more time caring for her.

Billy also had a memorable personal relationship with President Ronald Reagan. Their paths first crossed when Reagan was broadcasting Cubs games on the radio in Iowa. Reagan often recounted a story that happened in 1935, when the Cubs won 21 games in a row to edge the defending Cardinals for the pennant. His telegraph feed went dead just as a pitch came in to Jurges. Not wanting to lose the audience with a long gap of silence, he filled the air with a play that would not enter any record books. “And then he fouled one that missed a home run by a foot. And then he fouled one back to third base, and I described the kids that had a fight over the baseball. And he kept on fouling them until I was beginning to set a world record for a batter hitting successive fouls.” When the telegraph signals came back, Jurges had popped up on the first pitch. 33

Jurges remembered waiting with several Cubs teammates to meet their friend “Dutch,” as they knew Reagan, during spring training in California. “He had been to Hollywood to take a screen test. He wore glasses then, and we all kidded him. ‘You, take a screen test? As ugly as you are?’”34 Years later, in 1984 at the death of his wife, Jurges received a thoughtful phone call from the former broadcaster, then president of the United States.

During his career Jurges pursued several business interests, running parallel to his playing and coaching duties. In the early 1940s, he partnered with teammate Harry Danning to open a bowling alley, with a restaurant and cocktail lounge, on Long Island. Opening night featured broadcaster Mel Allen and baseball clown Al Schacht.

Jurges lived in his home area of New York City and spent winters at his cottage in Alexandria, Virginia. He did not like the climate in Sarasota, Florida, and sold his place there after only one year.35 He moved his family to Virginia in the 1950s and took a job with a manufacturing firm. He worked several years with the Little League there, serving as its commissioner, and joined the Grandstand Managers Club of Alexandria, promoting baseball throughout the area. He also opened a miniature-golf course and driving range and even dabbled in real estate and banking.

When he finally retired, Billy enjoyed life in Largo, Florida. “There’s a park adjacent to our house, and we play poker, pinochle, horseshoes, and dance,” said the 80-year-old Jurges in an interview with the Chicago Sun-Times.36 He also found time to travel with his second wife, Phyllis.

Billy devoted much of his off-field energy to his family. He delayed reporting to spring training with the Giants in 1942 because his daughter was sick and promptly became elected captain as soon as he showed up. When he got the job managing the Red Sox, he decided not to move to Boston because his daughter and granddaughter, Pinky, lived in Virginia. “If I moved to Boston permanently, I wouldn’t see Pinky,” He said.37

After receiving a grim diagnosis of cancer in 1991, Billy Jurges survived another six years, until he died on March 3, 1997, in Largo, Florida, at the age of 88.38 He had one daughter, Suzanne Price, two grandchildren, and two great-grandchildren.

His best memory came from his wedding day in 1933, when he got six hits against the Phillies. He said his main regret in his long career was that he did not accept Wrigley’s offer to manage the Cubs in 1938.39 He also regretted the clash with umpire Magerkurth. “That fight seems very funny now. It wasn’t funny when it happened.”40

“In my day, most of us were just crazy about baseball,” said Billy. “We just loved to play. All I ever wanted to do was play baseball. And once the game started, all I wanted to do was win.”41

Notes

1 Eddie Gold and Art Ahrens, “Billy Jurges,” The Golden Era Cubs 1876-1940 (Chicago: Bonus Books, 1985).

2 “Five Wild Weeks Give the Cubs a Succession of Varied Thrills,” The Sporting News, August 18, 1932.

3“Scribbled by Scribes,” The Sporting News, October 13, 1938.

4 Babe Ruth, as told to John P. Carmichael, ”My Greatest Diamond Thrill,” The Sporting News, March 23, 1944.

5 Leigh Montville, Big Bam: the Life and Times of Babe Ruth (New York: Doubleday, 2008).

6 “William Frederick Jurges,” The Sporting News, May 26, 1932.

7 Rich Westcott, Diamond Greats (Westport, Connecticut: Meckler Books, 1988).

8 Francis Stann. “Jurges Suggested Gabby as Pilot, Was Traded,” The Sporting News, October 29, 1958. Also documented in John Carmichael, “When Gabby Hartnett Hit His Homer in the Gloamin’,” Baseball Digest, October 1978.

9 “Fun with Frenchy, Casey and Babe,” The Sporting News, December 2, 1972.

10 Oscar Ruhl, “From the Ruhl Book,” The Sporting News, April 2, 1958.

11 Mike Hudson, “Brawl Games,” Roanoke (Virginia) Times, December 12, 2004.

12 The Sporting News, September 21, 1939.

13 Dick Young, “Young Ideas,” The Sporting News, March 9, 1960.

14 Bill Madden, “Harry Craft: Mick Mentor Had Seen All in Baseball,” New York Daily News, August 6, 1995.

15 J.G. Taylor Spink, “Stirring Wartime Pledges Mark Fun-Filled N.Y. Writers’ Frolic,” The Sporting News, February 5, 1942.

16 “Fanning with Farrington,” The Sporting News, January 16, 1941.

17 The Sporting News, July 11, 1940.

18 J.G. Taylor Spink. “Looping the Loops – Billy Jurges Joins New Team,” The Sporting News, December 15, 1948. The article quotes Jurges remembering the year incorrectly as 1934.

19 Ibid.

20 Bob Addie, “Bill Owed ‘It All to Cookie,’ His Spar Mate in Old-Time Rhubarb,” The Sporting News, July 15, 1959.

21 Hy Hurwitz, “Jurges Coaches at Third – ‘Can’t Sit Still on Bench,’” The Sporting News, July 15, 1959.

22 Jack Mann, “The Great Wall of Boston,” Sports Illustrated, June 28, 1965.

23 Jensen announced his retirement in late January, noting a desire to spend more time with his family. White refused to report to the Indians after being traded on March 16 and announced his retirement. Commissioner Ford Frick nullified the trade nine days later. White did not play in 1960, but in June 1961, the Red Sox sold his contract to the Milwaukee Braves. He finished his career in 1962 with the Phillies.

24 Stan Grosshandler, “Billy Jurges Recalls How It Was in Majors in 1930s,” Baseball Digest, October 1992.

25 Bob Chick, “Jurges: Howard the Aim in Seven-for-One Swap,” St. Petersburg Evening Independent, March 21, 1970.

26 Hy Hurwitz, “Hub Kids Pick Up Pointers in Classes at Jurges Tech,” The Sporting News, September 16, 1959.

27 “This turned out to be one of the sourest deals in Boston history and did more to depose Jurges and General Manager Bucky Harris than anything else.” Hy Hurwitz, “Hub Howitzer Wertz Ready for Fast Start,” The Sporting News, February 8, 1961.

28 Hy Hurwitz, “Baker Takes Hub Skipper Seat as Exhaustion Benches Jurges,” The Sporting News, June 15, 1960.

29 “Jurges Ailing; Baker Bosox’ Interim Pilot,” Milwaukee Sentinel, June 9, 1960.

30 Hy Hurwitz, “Return as Pilot May Boost Higgins to Hub G.M. Post,” The Sporting News, June 22, 1960.

31 “Jurges’ Skipper Job Cooked by Dish of Goulash, He Says,” The Sporting News, June 29, 1960.

32 Robert L. Burnes, “The Bench Warmer – High Spots and Some Low Ones,” The Sporting News, October 12, 1960.

33 “Remarks at the Mathews-Dickey Boys Club in St. Louis, Missouri,” July 22, 1982. http://www.reagan.utexas.edu/archives/speeches/1982/72282d.htm.

34 Westcott.

35 J.G. Taylor Spink, “Three and One: Looking Them Over with J. G. Taylor Spink,” The Sporting News, October 6, 1938.

36 Eddie Gold, “Ex-Cub Shortstop Billy Jurges,” Chicago Sun-Times, August 3, 1988.

37 Addie.

38 Tony Salin, “Chicago’s Blazing Shortstop: Billy Jurges,” Baseball’s Forgotten Heroes: One Fan’s Search for the Game’s Most Interesting Overlooked Players. Chicago: Masters Press, 1989.

39 Rich Phalen, Our Chicago Cubs (South Bend, Indiana: Diamond Communications, 1992).

40 Spink.

41 Westcott.

Full Name

William Frederick Jurges

Born

May 9, 1908 at Bronx, NY (USA)

Died

March 3, 1997 at Clearwater, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.