July 29, 1945: West offense lights up Comiskey Park to break deadlock in Negro League all-star series

The 1945 East-West Game at Comiskey Park in Chicago was the 15th installment of the popular matchup between the best players of the Negro American League and Negro National League. For the first half of the season, however, the possibility of the game was in doubt. World War II was still raging, and even though US Marines had raised the American flag on Mount Suribachi at Iwo Jima in February and Germany had surrendered in May, the United States was faced with the daunting challenge of a possible need to invade the Japanese mainland, and resources and manpower still needed to be rationed.1 In addition, some team executives, including Homestead Grays owner Cum Posey, were upset with arrangements surrounding previous East-West Games, raising the possibility that the game, which at this point had become an institution in Black society, would not be played.2 By June 12, however, all grievances and scheduling difficulties were cast aside when the US Office of Defense Transportation gave the Negro Leagues the green light to stage the game.3

The 1945 East-West Game at Comiskey Park in Chicago was the 15th installment of the popular matchup between the best players of the Negro American League and Negro National League. For the first half of the season, however, the possibility of the game was in doubt. World War II was still raging, and even though US Marines had raised the American flag on Mount Suribachi at Iwo Jima in February and Germany had surrendered in May, the United States was faced with the daunting challenge of a possible need to invade the Japanese mainland, and resources and manpower still needed to be rationed.1 In addition, some team executives, including Homestead Grays owner Cum Posey, were upset with arrangements surrounding previous East-West Games, raising the possibility that the game, which at this point had become an institution in Black society, would not be played.2 By June 12, however, all grievances and scheduling difficulties were cast aside when the US Office of Defense Transportation gave the Negro Leagues the green light to stage the game.3

The next day, team owners gathered at the Grand Hotel in Chicago and set the date of the 1945 East-West classic for Sunday, July 29.4 Black newspapers began hyping the game with editorials, and also published the ballots that fans used to elect their favorite players to the game. Many of the editorials rattled off the names of the most popular players of the time, enchanting fans with visions of coming baseball grandeur, and the two names most often mentioned were Homestead Grays catcher Josh Gibson and Kansas City Monarchs pitcher Satchel Paige. However, neither of the two superstars would play in the 1945 East-West Game.

It is debatable as to why Paige did not attend. He did not play in the 1944 game either.5 Two days before the game, the Kansas City Call reported that Paige would not pitch in the exhibition because of a sore arm.6 However, Pittsburgh Courier writer Wendell Smith reported on August 4 that Paige had skipped the game “because he could not reach an agreement with the East-West promoters financially.”7 Based on Paige’s notorious history of dealings with team owners and promoters, it is likely that he skipped the game because of an inability to negotiate a higher appearance fee.

Josh Gibson did not play in the game after being suspended by Posey for “a steady infraction of training rules,” which meant an extended drinking binge.8 It is possible that the binge was directly related to the illness that would eventually take his life a little more than two years later.9 Nevertheless, due to the suspension, Gibson was ineligible to play in the game.10

In a last-second move, the NAL removed Piper Davis of the Birmingham Black Barons from the team for hitting an umpire, an act that cost him $50.11 Davis was replaced by Jesse Williams of the Kansas City Monarchs.12 Additional controversy crept into the game when the FBI and Chicago police arrested several ticket scalpers and ticket counterfeiters who were charging markups in excess of 200 percent over face value. As a result of the markups, scores of tickets were unsold by game time.13

Despite the chaos, Chicago was buzzing in anticipation of the game. The Grand Hotel was “running over with baseball people.”14 Celebrities and baseball personalities were spotted inside Comiskey Park, adding to the allure of the event.15 Congressman William L. Dawson, who represented Illinois’ 1st District, threw out the ceremonial first pitch to Cook County Commissioner Mike Sneed, and the game was underway.16

Verdell Mathis, a left-hander for the Memphis Red Sox, started the game for the West. He retired Homestead Grays center fielder Jerry Benjamin to start the game, then walked Philadelphia Stars second baseman Frank Austin, who was promptly caught in a rundown on a pickoff play and chased down by Kansas City Monarchs shortstop Jackie Robinson for the first out. Mathis then struck out Newark Eagles left fielder Johnny Davis to end the top of the first. Baltimore Elite Giants left-handed pitcher Tom Glover took the mound for the East in the bottom of the first and retired the West in order. When Mathis retired the East’s batters in the top of the second, the game started to look like a pitchers’ duel.17

The offensive floodgates opened for the West when Memphis’s Neil Robinson led off the bottom of the second by beating out an infield hit. Cincinnati-Indianapolis Clowns third baseman Alex Radcliffe then smashed a drive to right field. On this bright July day in Chicago, Baltimore outfielder Wild Bill Wright18 was not wearing sunglasses, lost the ball in the sun, and it rolled into deep right field. Robinson ended up on third and Radcliffe at second.

The next batter, Cleveland Buckeyes first baseman Archie Ware, lifted a lazy single over Philadelphia Stars second baseman Frank Austin’s head to drive in Robinson and Radcliffe for the first two runs of the game. Baltimore catcher Roy Campanella threw out Ware attempting to steal second base, but Cleveland catcher-manager Quincy Trouppe drew a one-out walk, and then was singled to third by Mathis, helping his own cause.

At that point, East manager Vic Harris pulled Gordon from the mound and sent in Philadelphia Stars right-hander Bill Ricks. Jesse Williams, the last-minute replacement for Piper Davis, lifted an 0-and-1 pitch to right field. Incredibly, Wright, still refusing to don sunglasses, lost another ball in the sun. Trouppe and Mathis were able to coast home, and Williams ended up on third with a triple. Ricks then got out of the inning by retiring Jackie Robinson, appearing in his first and only East-West Game.19 At the end of the second, the West led 4-0.

Mathis cruised through the top of the third without allowing a hit.20 Cleveland right fielder Lloyd Davenport led off the bottom of the third inning with a groundout, but back-to-back singles by Neil Robinson and Alex Radcliff put runners at the corners. Birmingham Black Barons left fielder Lester Lockett stepped up to the plate and hit a grounder toward shortstop Willie Wells, whose only play was at first. Robinson scored, with Radcliff taking second. Radcliff scored a moment later on Ware’s second hit to right, this one a sizzling liner. Trouppe then drew his second walk of the game and Mathis picked up his second hit on a slow roller to Wells that he beat out for an infield hit. Jesse Williams then gave the West a commanding 8-0 lead with a single to left to score Ware and Trouppe. East manager Harris relieved Ricks with New York Cuban Stars multipositional wizard Martin Dihigo, who came in from right field to pitch.21 The game was effectively decided at this point.

Chicago American Giants right-hander Gentry Jessup took over for Mathis in the fourth and blanked the East for three more innings. The West added a run in the bottom of the fourth inning when Davenport led off with a double, took third on a bunt by Neil Robinson, and scored on Alex Radcliff’s groundout.22 At the end of the fourth inning, the West was leading 9-0.23

The East finally got on the scoreboard in the top of the seventh when Kansas City Monarchs right-hander Booker McDaniel relieved Jessup and walked Cuban Stars right fielder Rogelio Linares, who took second on Newark Eagles third baseman Murray Watkins’ single. Lennie Pearson pinch-hit for Martin Dihigo and forced Watkins out, putting Linares at third and Pearson at first. Jerry Benjamin then hit into another fielder’s choice, forcing Pearson at second and scoring Linares for the first East run of the game. McDaniel gave up a single to Cuban Stars shortstop Horacio Martínez, which drove in Benjamin, before getting Philadelphia Stars left fielder Gene Benson to ground out to retire the side.24 At the end of the seventh inning, the West led 9-1.

The East team made things interesting in the top of the ninth. Murray Watkins led off with a single and was forced at second when Bill Byrd of the Baltimore Elite Giants, pinch-hitting for Homestead Grays pitcher Roy Welmaker, reached on a grounder. Jerry Benjamin and Horacio Martinez struck back-to-back singles, with Byrd and Benjamin scoring on the second hit to make the score 9-3. Gene Benson hit into a fielder’s choice, then took second on a walk to Homestead Grays first baseman Buck Leonard. Roy Campanella then singled in Benson to make it 9-4, prompting East manager Winfield Welch to relieve Booker McDaniel with Buckeyes pitcher Gene Bremer. Bremer immediately gave up a bases-clearing double to Willie Wells, but then got Rogelio Linares to ground out – Jackie Robinson to Archie Ware – to end the game.25 Roy Glover took the loss, with Mathis earning the win and Gene Bremer picking up the save.26 The West won, 9-6.

A crowd of 37,714 attended the game.27 The controversy surrounding ticket scalpers and counterfeiters seemed to have hurt attendance.28 The absence of Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson most likely affected attendance as well.29 Two years later, Jackie Robinson would make his debut for the Brooklyn Dodgers, marking the beginning of the end of the Negro Leagues and their beloved summer all-star game.30

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Seamheads.com and Baseball-Reference.com.

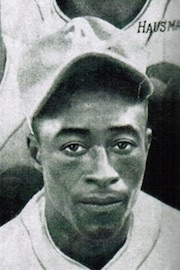

Photo credit: Jesse Williams, Seamheads.com.

Notes

1 “ODT Ruling Hits East-West Game, Negro Baseball and Pro Sport,” Chicago Defender, March 3, 1945. The Office of Defense Transportation asked baseball owners to reduce travel by 25 percent, and as a result the White American and National Leagues announced that they would not stage an All-Star Game for the 1945 season

2 “Scalpers take good beating,” Chicago Defender, August 4, 1945. Homestead Grays owner Cum Posey objected to Chicago American Giants owner Dr. J.B. Martin’s influence over the game, especially the flow of the gate receipts. Posey suggested that Martin skimmed money off the top of the gate in order to make up what he lost due to the East-West Game. Despite the game’s immense popularity, especially among Chicago residents, Posey claimed that the game actually caused Wilson to lose money. Posey’s theory was that Martin took much higher percentages of the gate receipts on non-all-star weekends, since the gate of the East-West Game was split between every NAL and NNL player and team. (East-West players received $100, coaches received $300, and $300 went to every league team to be divided among players not selected to the game.) He also theorized that the ability for Martin’s American Giants to draw fans during the weekends prior to and after the East-West Game were stunted due to the game’s popularity, further decreasing his team’s earning potential, and giving Martin motivation to skim the gate. NAL President Martin and NNL President and Baltimore Elite Giants owner Tom Wilson had formed a committee consisting of owners Ernie Wright of Cleveland, Tom Baird of Kansas City, Alex Pompez of New York, and Abe Manley of the Newark Eagles, after the previous year’s East-West Game, to find ways to improve the exhibition. Posey encouraged the committee to consider their grievances.

3 “No commissioner yet,” Baltimore Afro-American, June 23, 1945. Originally, the four-man committee decided that due to Office of Defense Transportation travel restrictions, the game would not be staged. Negotiations between the committee and the ODT went back and forth. On May 9 the ODT lifted restrictions on dog and horse racing, eliminated a midnight curfew, and announced an increase in the amount of gasoline that would be available to civilians, giving hope to the committee and baseball fans that the East-West Game would be played. However, when the committee approached the ODT with their plans to organize the game, the ODT “was found to frown on the affair.” J.B. Martin had persuaded the ODT to allow the leagues to play the game by claiming that the fans attending the game would be almost exclusively from Chicago. Neil Lanctot, Negro League Baseball: The Rise and Ruin of a Black Institution (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004), 253.

4 “East-West Game Will Be Played on July 29,” Chicago Defender, June 23, 1945.

5 Satchel Paige, Maybe I’ll Pitch Forever (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1993), 159-167. In Paige’s autobiography, he claims that he persuaded Josh Gibson to hold out of the 1943 East-West Game with him for more money. After negotiations with J.B. Martin and Tom Wilson, both players received secret $200 bonuses for playing. When the 1944 game rolled around, Paige came up with the idea to donate the gate receipts from the game to charities for soldiers returning from the war, but was met with the cold shoulder from NAL and NNL owners. Incensed, Paige refused to participate in the game. Russ J. Cowan, “Paige Threatens to Bolt East-West Game,” Michigan Chronicle (Detroit), August 5, 1944.

6 “Satchel Won’t Hurl in Dream Classic in Chicago on Sunday,” Kansas City Call, July 27, 1945.

7 Wendell Smith, “The Sports Beat,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 4, 1945.

8 “Through the Eyes of W. Rollo Wilson,” Philadelphia Tribune, August 11, 1945.

9 William Brashler, Josh Gibson: A Life in the Negro Leagues (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2000), 125-136. Despite his monstrous appearance and incredible athletic ability, by 1945 Josh Gibson was suffering immensely both physically and mentally. Gibson lost consciousness and slipped into a coma on New Year’s Day 1943. It was soon discovered that he was suffering from a brain tumor. Despite the seriousness of the diagnosis, Josh kept the tumor a secret, refused treatment, and began turning to alcohol and marijuana to ease the pain and the depression that was quickly sinking into his life. He became prone to dizziness and headaches. His increasing substance abuse, along with the growing tumor, began to cause him to have psychotic episodes. He died on January 20, 1947, at the age of 35.

10 “Through the Eyes of W. Rollo Wilson,” Philadelphia Tribune, August 11, 1945. Cum Posey was a dominant force in Negro Leagues baseball throughout the 1930s, up to his death in 1946. On the morning of the East-West Game, he held court in the Grand Hotel lobby, talking baseball and shopping his suffering catcher, Josh Gibson. He offered to trade Gibson to the Baltimore Elite Giants for Roy Campanella, and club owner Wilson laughed him right out of the lobby, emphasizing how low Gibson’s stock as a player had sunk since he had begun showing signs of a serious mental illness.

11 “NAL player fined for striking umpire,” Baltimore Afro-American, July 28, 1945. Davis was voted in by fans as the NAL starting second baseman, but had been suspended indefinitely by J.B. Martin and fined $50 for striking umpire Jimmy Thompson with a baseball bat during a heated argument in a game between Birmingham and the Cleveland Buckeyes on July 16.

12 Wendell Smith, “The Sports Beat.”

13 “Scalpers Take a Good Beating,” Chicago Defender, August 4, 1945. “FBI Nabs Ticket Counterfeiters at East-West Game,” New Journal and Guide (Norfolk, Virginia), August 11, 1945. Rumors had spread before the game that the park had been sold out, when in fact there were thousands of tickets left for sale. The markups by scalpers further depressed attendance. Grandstand tickets with a face value of $2 were being sold by scalpers for $4, and $7.50 box-seat tickets were selling for as high as $10.

14 Wendell Smith, “The Sports Beat.”

15 Al Monroe, “Swinging the News,” Chicago Defender, August 11, 1945. Inside Comiskey Park, celebrities like Lena Horne, Roberta Proctor, and Earl Robinson were spotted in the stands. John R. Williams, a Detroit baseball promoter, walked throughout the stands, engaging team executives and trying to book games at Briggs Stadium. Missing from the assemblage of baseball personalities were Newark Eagles owner, and baseball’s only female member of the Hall of Fame, Effa Manley; Kansas City Monarchs owner J.L. Wilkinson; and Gus Greenlee, former Pittsburgh Crawfords owner who had recently partnered with Brooklyn Dodgers President Branch Rickey to start a third Negro League, the United States League. In his column “The Sports Beat,” Wendell Smith wrote that Wilkinson felt ill and was resting at his home in Kansas City, and that Greenlee was occupied caring for his sick mother.

16 “Scalpers Take a Good Beating.”

17 Wendell Smith, “West Wallops East in Dull ‘Dream Game,’ 9 to 6,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 4, 1945; “West Captures Lead in 9-6 Series Win,” Philadelphia Tribune, August 4, 1945.

18 Radcliffe was the brother of Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe. Contemporary newspapers dubbed Wright “Big Bill Wright.”

19 “West Wallops East in Dull ‘Dream Game,’ 9 to 6”; Associated Negro Press, “West Defeats East 9-6 Before 32,000 Fans,” New Journal and Guide, August 4, 1945.

20 “West Wallops East in Dull ‘Dream Game,’ 9 to 6.” Verdell Mathis was lifted after three innings because owners had agreed to a three-inning limit for all pitchers. He struck out four and walked one in three innings.

21 “West Wallops East in Dull ‘Dream Game,’ 9 to 6.” Martin Dihigo is the only baseball player to be elected to Halls of Fame in five countries – the United States, Cuba, Mexico, Venezuela, and the Dominican Republic. He was a multipositional player who earned the nicknames El Inmortal and El Maestro for his mastery of every position, and also for his managing abilities. He was the starting right fielder for the East team in the 1945 East-West Game.

22 “West Captures Annual Diamond Classic, 9-6,” St. Louis Argus, August 3, 1945.

23 “West Wallops East in Dull ‘Dream Game,’ 9 to 6.”

24 “West Wallops East in Dull ‘Dream Game,’ 9 to 6.”

25 “West Captures Annual Diamond Classic, 9-6.”

26 “West Wallops East in Dull ‘Dream Game,’ 9 to 6.”

27 Dan Burley, “Dan Burley’s ‘Confidentially Yours,’” New York Amsterdam News, August 18, 1945. While the reported attendance figure of 37,714 would have been considered a very large crowd for a regular-season NAL or NNL game, for the celebrated East-West Game, the total was a far cry from previous games. Attendance the two years prior had reached over 50,000 fans. Pittsburgh Courier sportswriter Wendell Smith, in his column “The Sports Beat,” attributed the drop-off in attendance to several reasons. Traditionally, the East-West game was played in the first week of August, but for the 1945 season owners had voted to move the game up to July. ODT travel restrictions hampered the ability of patrons to travel to Chicago for the game

28 “Scalpers Take Good Beating.”

29 Willie Bea Harmon, “Sportorial,” Kansas City Call, July 27, 1945. Newspapers were promoting the appearances of Paige and Gibson the week of the game. Even the Kansas City Call, which was the only paper that reported that Paige would miss the game, ran another article in the same edition promoting Paige in the West lineup.

30 Lawrence D. Hogan, Shades of Glory (Washington: National Geographic, 2006), 357-372. The 1945 game was not only Jackie Robinson’s only East-West appearance; it was his only season in Negro League baseball. On October 23, 1945, the Brooklyn Dodgers announced that they had signed Robinson to a contract and assigned him to their minor-league affiliate in Montreal for the 1946 season. On April 15, 1947, Robinson made his debut at first base for the Dodgers and broke a color barrier that had existed in major-league baseball since the mid-1880s. The New York Giants, Cleveland Indians and other teams started quickly signing as many Black baseball players as they could. The talent pool in the Negro Leagues depreciated rapidly. By the 1949 season, the level of play had sunk so low that Major League Baseball does not recognize Negro League seasons after 1948 as being major-league caliber. In 1948 the East-West Game drew 31,079 fans, of whom only 26,697 bought a ticket. By 1951, game attendance had fallen to 21,312, of whom 14,161 paid to see the game. Attendance for the 1954 game was estimated at around 10,000. The game moved from Comiskey Park, its home since its inception in 1933, to Yankee Stadium in 1961, the next to last East-West Game. The ageless Satchel Paige, at the time 55 years old (yet still four years away from his final major-league appearance in 1965 at the age of 59 for the Kansas City Athletics) pitched for the West team, giving up only one hit in a 7-1 West win. The attendance at the game was 7,245, a far cry from the era when celebrities and politicians would join the masses to pack into Comiskey Park and root on the cream of the crop of Black baseball talent during the heyday of the Negro Leagues.

Additional Stats

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.