June 24, 1979: Rickey Henderson makes his major-league debut for Oakland A’s

By late June 1979, the once-proud Oakland Athletics had fallen into baseball’s basement.

By late June 1979, the once-proud Oakland Athletics had fallen into baseball’s basement.

After 13 wayward seasons in Kansas City without a winning record, the franchise arrived in Oakland in 1968 with future stars Reggie Jackson, Sal Bando, Bert Campaneris, and Catfish Hunter on the roster. The early 1970s saw five straight division titles and three consecutive World Series championships.

Then Hunter ushered in free agency after the 1974 season when an arbitrator agreed with his breach-of-contract claim.1 He left for the New York Yankees.2 Jackson and Ken Holtzman were traded to the Baltimore Orioles in April 1976.3 Bando, Campaneris, Joe Rudi, Gene Tenace, and Rollie Fingers left as free agents in the 1976-77 offseason, and a string of nine straight winning seasons was snapped in 1977. Vida Blue was the last to go, shipped across the Bay to the San Francisco Giants in March 1978 for seven role players and cash.4

Owner Charles Finley cycled through managers at a Steinbrenneresque clip. Jim Marshall was hired in 1979, Oakland’s ninth manager in 11 years. “Around here, you learn to expect the unexpected,” said third baseman Wayne Gross upon learning that Bobby Winkles, who had managed parts of 1977 and 1978, had walked out on Finley a few hours before a game.5

Meanwhile, the Athletics’ woes became existential when Finley announced the sale of the team to Denver oilman Marvin Davis, who planned to move the franchise immediately. “A’s Fans React: Anger, Apathy” headlined the Oakland Tribune on December 15, 1977.6 Written by Ralph Wiley, who coined the term “Billy Ball” in 1980, the news was a gut-punch to a baseball community betrayed by Finley’s fire sale.7

As play began on Sunday, June 24, 1979, Oakland had the worst record in baseball at 22-50. Total attendance in the first six games of the A’s homestand was 16,361. Earlier in the season, on a chilly Tuesday night against the Seattle Mariners, Oakland attendance bottomed out at 653 fans.8 An Oakland Raiders softball exhibition on June 24 against the Alameda Police Department drew 4,300 to Washington Park, more than the A’s average attendance for the season and just a few hundred fans less than Oakland’s doubleheader with the Texas Rangers drew that day.9

Oakland had lost in 10 innings on June 23. Starting left fielder Derek Bryant, a 27-year-old rookie, went 0-for-4, lowering his average to .165 in what would be his only major-league season. He was already the A’s eighth left fielder of the season.

Three of them – Bryant, Larry Murray, and Opening Day starter Glenn Burke – were soon out of the league. Miguel Diloné, frustrated in Oakland, chased manager Marshall with a bat before the June 24 doubleheader; he was demoted and then sold to the Chicago Cubs.10 June 15 trade deadline acquisition Mike Heath was a catcher playing out of position, and 1977 rookie sensation Mitchell Page was only 27 but his best days were past.

Tony Armas and Dwayne Murphy were both promising outfielders with a bright future next to the newest Oakland Athletic promoted for the doubleheader – Rickey Nelson Henley Henderson.

Born on Christmas Day in 1958 in Chicago, Henderson was raised in Arkansas. His mother moved the family to Oakland a year after the A’s arrived. The last pick in the fourth round of the June 1976 amateur draft from Oakland Technical High School, Henderson had laid waste to the minor leagues for parts of four seasons.11

Starting for the A’s in the first game of the doubleheader was 23-year-old right-hander Matt Keough. Oakland’s only All-Star Game representative in 1978, Keough was winless through 16 starts so far in ’79, posting an 0-8 record and a 5.62 ERA.

Making only his second start for Texas was former Athletic John Henry Johnson. Drafted by the Giants in 1974, he came to Oakland in the Blue trade. A decent season in the Bay (11-10, 3.39 ERA in 30 starts) was followed by a rough start to 1979 (2-8, 4.36 in Oakland) before the 22-year-old Johnson went to the Rangers in the deal that brought Heath to Oakland.

Keough pitched a scoreless first. Bump Wills led off with a single to right, but Buddy Bell hit into a 6-4-3 double play and Pat Putnam struck out.

Henderson led off the bottom of the first, sporting the white pullover jersey top with yellow numbers on the back and green and gold trim. His name was not on his jersey and he wore number 39.12 Getting into his signature crouch, though not as exaggerated as it would be later in his career, Henderson laced a double down the right-field line, sliding headfirst ahead of the throw from Oscar Gamble.

A single by Dave Chalk – another part of Oakland’s return for Johnson – moved Henderson to third but Gross flied out to second. The inning ended when Jeff Newman flied out to right field and Henderson was nailed at the plate by a fine throw from Gamble.

Keough pitched out of a bases-loaded jam in the second inning with a strikeout and a fly out, and Johnson pitched around two walks to keep Oakland off the board in the bottom of the inning.

In the bottom of the third, Henderson batted with one out and singled to left for his second hit in two at-bats. Chalk flied out as Henderson measured the battery of Johnson and Gold Glove catcher Jim Sundberg. It was an imposing duo to run against. Johnson had allowed just five stolen bases in 1978 against 10 caught stealing, and baserunners had a less than 50/50 chance against him in his career. Sundberg was in his fourth of six consecutive Gold Glove seasons and had led the AL in throwing out basestealers the prior three seasons.

With a feet-first slide, however, Henderson hit the right side of the base just ahead of shortstop Larvell Blanks’ tag. The official attendance of 4,752 diehards had just witnessed the 20-year-old’s first 90-foot dash toward baseball immortality.

The Rangers finally found the plate in the fifth inning. Consecutive one-out singles by Blanks, Wills, and Bell loaded the bases for Putnam, whose single up the middle scored two runs. John Ellis followed with a three-run home run, his seventh, blowing the game open. Gamble singled and Johnny Grubb, the ninth batter of the inning, singled but was caught in a rundown between first and second and the inning was over. “The guy had good stuff all game,” Ellis told the Dallas Morning News. “We just kinda bunched up on him that one inning.”13

The A’s went quietly in the bottom of the fifth, Henderson flying out to end the inning.

Oakland got on the board in the sixth with two walks and a two-out single by Page, scoring Gross and cutting the deficit to 5-1.

Too late, Keough found his groove, facing the minimum 12 batters over the final four innings. The Athletics went in order in the seventh, Henderson flying out again to end the inning. A leadoff single by Chalk in the eighth chased Johnson. Jim Kern gave up a single to Gross but struck out Newman and induced two fly outs to end the threat. Oakland went quietly in the ninth.

Johnson was credited with his second win in a row with Texas. He wouldn’t win again that season, finishing 4-14. Keough’s record fell to 0-9. He finished 2-17, but the complete game was a sign of things to come. He bounced back in 1980, throwing 20 complete games with a sub-3.00 ERA in 250 innings.

Marshall committed to Henderson for the rest of the season, resting him only once and starting him 59 times in left field, 28 in center, and once in right. Henderson led off every game, batting .274 overall but .309 in the first inning, including the first of his record-setting 81 leadoff home runs at the Coliseum on September 18 in front of 750 spectators.

The A’s lost the second game of the June 24 doubleheader, 7-2; Henderson was 0-for-4. Oakland wouldn’t win for another week, ending an eight-game skid in Texas the following Sunday, after which Henderson switched his number to 35.14 Henderson’s debut coincided with a 4-25 slide, a 108-loss finish,15 and an unceremonious end to Marshall’s managing career.

The 1980 season was a different story: Billy Martin coming home, “Billy Ball,” a surprise contender, a league-best staff ERA and 94 complete games, and Murphy, Armas, and Henderson forming the best outfield in the game, peaking with an AL Championship Series appearance against the Yankees in 1981. In August of 1980, Finley sold the A’s locally to Levi-Strauss CEO Walter Haas Jr., who kept the team in Oakland.

Asked later in the 1979 season what he’d like the team to focus on, Henderson replied, “I would like the team to run more.”16 The next season, the future Hall of Famer stole 100 bases for Martin’s A’s, the first of 12 times he led the AL.

Acknowledgments

This story was reviewed by Gary Belleville, Kurt Blumenau, and John Fredland; fact-checked by Bruce Slutsky; and copy-edited by Len Levin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author relied upon Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org for player, team, and season information and the following:

https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/OAK/OAK197906241.shtml

https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1979/B06241OAK1979.htm

https://www.youtube.cFom/watch?v=NIjfV_b9m8o

Tafoya, Dale. Billy Ball: Billy Martin and the Resurrection of the Oakland A’s (Essex, Connecticut: Rowman & Littlefield, 2020).

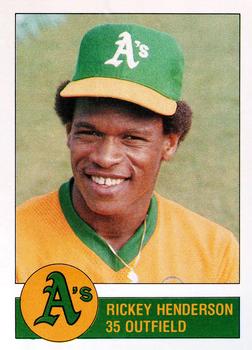

Photo credit: Rickey Henderson, Trading Card Database.

Notes

1 Arbitrator Peter Seitz ruled that the A’s had breached Hunter’s contract by not making scheduled payments of deferred compensation during the 1974 season. Stew Thornley, “The Demise of the Reserve Clause: The Players’ Path to Freedom,” SABR Baseball Research Journal, Vol 35 (2006), 118, https://sabr.org/journal/article/the-demise-of-the-reserve-clause-the-players-path-to-freedom/.

2 Murray Chass, “Yankees Sign Up Catfish Hunter in Estimated $3.75-Million Deal,” New York Times, January 1, 1975: 1.

3 Ron Bergman, “Athletics Infuriated Over Trade,” Oakland Tribune, April 4, 1976: 5C.

4 Tom Weir, “Kuhn Expected to OK Giants’ Deal for Blue,” Oakland Tribune, March 16, 1978: 1.

5 Ralph Wiley, “A’s Players Take News in Stride,” Oakland Tribune, May 24, 1978: 37.

6 Ralph Wiley, “A’s Fans React: Anger, Apathy,” Oakland Tribune, December 15, 1977: 1.

7 Jon Thurber, “Ralph Wiley, 52; Sportswriter and Author of Books on Race,” Los Angeles Times, June 16, 2004: B8.

8 Tom Weir, “A’s Chill Mariners Before 653 Fans,” Oakland Tribune, April 18, 1979: B49.

9 “4,300 See Raider Win in Lob Ball,” Oakland Tribune, June 25, 1979: 37. Total attendance at the Coliseum in 1979 was 306,763, according to Baseball-Reference, an average of 3,787 per game, and less than half that of the next lowest team, Atlanta, which drew 769,465 to Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium.

10 Tom Weir, “Dilone Goes After A’s Pilot With Bat,” Oakland Tribune, June 25, 1979: D-13; “A’s Sell Dilone to Cubs,” Oakland Tribune, July 4, 1979: D-2.

11 Henderson hit .336 in the Northwest League in 1976, stealing 29 bases in 46 games. He swiped 95 bags and drew 104 walks in 134 games in the California League in 1977, batting .345. He stole 88 more bases in Double-A Jersey City the next season and had already stolen 44 bases in 71 games in Triple-A Ogden by late June of 1979.

12 Brief clips of Henderson’s debut can be found online. The Rickey Henderson Collectibles site (“June 24, 1979: Rickey’s MLB Debut,” Rickey Henderson Collectibles, http://www.rickeyhendersoncollectibles.com/2008/06/june-24-1979-rickeys-mlb-debut.html, accessed October 16, 2024) has a few photos that appear to be taken from a short ESPN video (“On This Date: Rickey Henderson made his MLB debut,” Facebook Video (ESPN.com), 0:29, https://www.facebook.com/ESPN/videos/on-this-date-rickey-henderson-made-his-mlb-debut/2146915288688549/, accessed October 16, 2024). At the 0:08 mark, first-base coach Lee Walls is clearly visible with his name on his jersey while Henderson flashes by without a name. The ESPN clip includes Henderson’s first hit and his first stolen base, going feet first into second base. Another highlight video found on YouTube (“1979 NYY@OAK, Heath makes running catch, hits wall,” YouTube video (Classic MLB1), 1:31, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NIjfV_b9m8o, accessed October 16, 2024), probably from a Sunday afternoon game on July 8, shows a crowd of Athletics gathering around Mike Heath after he ran into a wall in left field. At the 0:56 mark, Henderson, glove on his right hand and still wearing number 39 without his name, is clearly visible. The video doesn’t include a date but seems to depict New York’s Jim Spencer (number 12) flying out to Heath in left against Brian Kingman (number 50). The only game that matches that scenario is July 8, 1979, according to the Baseball-Reference game log.

13 Randy Galloway, “Texas Wins Pair; Ties KC for Second,” Dallas Morning News, June 25, 1979: 1B.

14 Howard Bryant, Rickey: The Life and Legend of an American Original (New York: HarperCollins, 2022), 71. The timing of Henderson’s switch to number 35 may have been later than this game on July 1 if the YouTube video “1979 NYY@OAK, Heath Makes Running Catch, Hits Wall” indeed reflects action on July 8, 1979, against New York.

15 It was the A’s most losses in a season in Oakland until they lost 112 games in 2023.

16 Tom Weir, “Kid Henderson Man of Month in Oakland,” The Sporting News, August 4, 1979: 19.

Additional Stats

Texas Rangers 5

Oakland Athletics 1

Game 1, DH

Oakland-Alameda County Coliseum

Oakland, CA

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.