October 6, 1919: Hod Eller scatters three hits, fans nine to lead Reds in Game 5

Boasting a three-games-to-one lead after four tilts, the Reds had all but started counting their share of the 1919 World Series take. “With three victories to our credit, nothing will stop the Reds now of winning the world’s championship,” Cincinnati skipper Pat Moran declared before they were to face the White Sox at Comiskey Park in Game Five.1

Boasting a three-games-to-one lead after four tilts, the Reds had all but started counting their share of the 1919 World Series take. “With three victories to our credit, nothing will stop the Reds now of winning the world’s championship,” Cincinnati skipper Pat Moran declared before they were to face the White Sox at Comiskey Park in Game Five.1

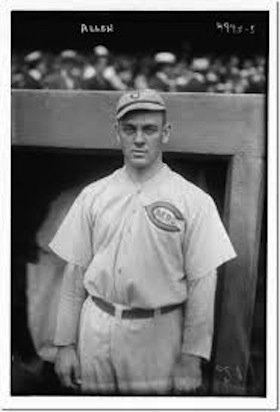

Moran also insisted his pitching staff was “vastly superior” to Chicago’s and, as if to prove it, he sent 19-game winner and shine-ball artist Hod Eller to the mound to face Lefty Williams instead of ace and Game One winner Dutch Ruether.2

Eller had gone to spring training with the White Sox in 1916 and legend was that he learned the shine ball from Eddie Cicotte and Dave Danforth. But according to biographer Stephen V. Rice, Eller learned the pitch accidentally while trying to get a better grip on the ball during a game against the New York Giants in 1917.3 Eller mastered the pitch and went 45-26 with a 2.37 ERA for the Reds from 1917 to 1919.

The White Sox had spent part of the previous day, a soggy Sunday that pushed Game Five back a day, criticizing themselves and each other for plays they should have made in their three losses. But when a reporter remarked that the loser’s share would be close to $4,000, he was told to go to hell.4

Monday was sunny and the game was played under a cloudless sky, but it was cold and the field was still damp and slippery even after the best efforts of laborers, who did all they could to get it in playing shape. Despite the chill in the air, attendance was 34,379 and would prove to be the highest of the Series. Once again the masses were treated to a brilliant pitching performance and once again Chicagoans would be sent home without a win. In a pattern that was becoming all too familiar in Chicago’s losses, the White Sox suffered through a tumultuous inning that would lead to their downfall. This time it was the sixth.

- Learn more: Click here to view SABR’s Eight Myths Out project on common misconceptions about the Black Sox Scandal

Williams took the hill and fired his first pitch to Morrie Rath, a ball that was a foot outside. Five pitches later, Rath was on first with a walk, the seventh free pass issued by Williams in only 32 batters. Jake Daubert followed with a perfectly executed sacrifice bunt that sent Rath to second, but Williams got Heine Groh to fly to Happy Felsch, and Edd Roush to ground to Chick Gandil to end the inning.5 According to the Buffalo Evening News, Williams’s curve was breaking “very sharply” and he “worked the corners repeatedly.”6

Eller struggled in his half of the inning and only a call that went against the White Sox kept them from loading the bases with one out. Nemo Leibold led off for Chicago and drew a seven-pitch walk that had the crowd responding with great enthusiasm.7 Eddie Collins took two balls before Daubert went to the mound to settle Eller down. Collins took a strike, then grounded to shortstop Larry Kopf, who barely nipped the speedy runner at first. Collins thought he was safe and “protested vigorously,” to no avail.8 Leibold advanced to second on the play and might have scored had Eller not knocked down Buck Weaver’s hit up the middle, but he stopped at third and the White Sox had runners at the corners with the heart of the order coming up. Moran took no chances and ordered ace reliever Dolf Luque to warm up.

It proved to be unnecessary. Joe Jackson hit a towering popup to Groh at third, Felsch followed with a fly ball to Pat Duncan in left, and the threat was over. So were the White Sox’ hopes; they would put only two men on base the rest of the way. Of course the fans didn’t know that and they continued to cheer their boys on, especially when Williams fanned Duncan and Greasy Neale in the top of the second, which brought the fans to their feet “with a great roar.” 9 The southpaw was mixing his curve with a “slow one” with great success.10

Eller did Williams one better in the bottom of the frame and struck out Gandil, Swede Risberg, and Ray Schalk with a “wicked” shine ball that had Risberg so fooled he dodged out of the way of a pitch that swerved over the heart of the plate.11 Williams continued mixing his pitches effectively, but changed things up in the third and relied heavily on a combination of fastballs and “underhand floaters” to retire the Reds easily.12

Not to be outdone, Eller made history when he struck out Williams, Leibold, and Collins in succession, giving him six straight punchouts, a World Series record, and thousands of new fans, who “rose with a mighty cheer” after his third strike sizzled past Collins’s bat.13 The Reds put a man at second in the top of the fourth when Roush reached first on shortstop Risberg’s miscue with two outs, then advanced on a steal attempt made easier when Schalk dropped the pitch. But Duncan flied out to Jackson and the game went to the bottom of the inning still scoreless.

Weaver broke Eller’s strikeout streak with a weak tap to the pitcher, but the 25-year-old righty continued to mesmerize White Sox batters and shut down Jackson on a grounder to the box before fanning Felsch on three pitches. Cincinnati had no answers for Williams in the fifth, but catcher Bill Rariden and an ingenious fan entertained the throng when Rariden skied a foul to right that was caught in the mouth of a megaphone, much to the crowd’s delight.14

The White Sox put a man on first thanks to a two-out single to left by Schalk, but Eller struck out Williams to send the game to the fateful sixth. Eller led off the inning and he was no slouch at the plate, having batted .280 with a .409 slugging percentage during the regular season. “Eller was … known as a dead pull hitter to left,” wrote William A. Cook. But when Eller came up in the third inning White Sox manager Kid Gleason “pulled Happy Felsch over toward right leaving a gap between center and left.”15

Gleason waved Felsch toward right again in the sixth and Eller made the White Sox pay with a double to left center made worse when Felsch heaved wildly to the infield and Risberg deflected the ball far enough away for Eller to go to third. Rath sent Eller home with a sharp single to right on a two-strike pitch and the Reds went up 1-0. Daubert sacrificed again and Rath was on second with one out. Williams was careful with Groh and walked him on four pitches, the second of which Williams and Schalk argued was a strike.16

Accounts of what happened next differ somewhat depending on who’s telling the story, but the result was the same regardless. Roush sent a fly to center that Felsch misplayed before racing back, catching up to it, and snagging the ball out of the air only to drop it. What followed was a comedy of errors that had Felsch slipping, falling, and dropping the ball again before he fired it to the infield where Collins corralled it and heaved to Schalk in an effort to nab Groh at home.17 The latter slid past Schalk and umpire Cy Rigler called him safe, sending Schalk into a rage and out of the game after he bumped Rigler during his tirade.

By the time the dust settled, the Reds had plated three runs. Duncan’s sacrifice fly four pitches later gave the boys from the Queen City a 4-0 cushion before Williams could escape the inning. Eller continued to be largely unhittable and retired 12 of the last 13 White Sox, the lone blemish being Weaver’s triple with two outs in the ninth. Cincinnati manufactured a run in the top of the ninth against Erskine Mayer on an error, walk, sacrifice bunt, and groundout to put the finishing touches on the 5-0 victory.

This article will be published in an upcoming SABR Digital Library book on the greatest games at Comiskey Park.

Sources

In addition to the sources mentioned in the notes, the author consulted baseball-reference.com and retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 “Can’t Stop Reds … Moran,” Baltimore Sun, October 5, 1919.

2 Ibid.

3 Hod Eller biography, Society for American Baseball Research, sabr.org/bioproj/person/32e0ca8c.

4 Eliot Asinof, Eight Men Out (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1963), 117.

5 “Reds Win Again,” Buffalo Evening News, October 6, 1919.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 Bill James and Rob Neyer, The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers: An Historical Compendium of Pitching, Pitchers, and Pitches (New York: Fireside, 2004), 21. According to Rob Neyer, a slow ball was most commonly linked to the palm ball based on how contemporary pitchers demonstrated their grip.

11 “Reds Win Again.”

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid.

15 William A. Cook, The 1919 World Series: What Really Happened? (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2001), 60-61.

16 “Marvelous Box Work of Eller Cops for Reds,” Moline (Illinois) Daily Dispatch, October 6, 1919.

17 Cook wrote that Felsch was inexplicably playing shallow with slugger Edd Roush at the plate and that his first step was forward before he raced back and caught up to the ball, only to drop it as he slipped and fell. Eliot Asinof wrote in Eight Men Out that Roush’s fly was a “towering shot to deep center field,” that Felsch turned “at the crack of the bat and tore after it” while the crowd anticipated a typical Felsch grab, except that the outfielder turned too soon, slowed down, started again, turned again, lost sight of the ball, located it again, sped up and tracked it down, only to drop it. Then he slipped, fell, got up and grabbed the ball, dropped it, and grabbed it again.

Additional Stats

Cincinnati Reds 5

Chicago White Sox 0

Game 5, WS

Comiskey Park

Chicago, IL

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.