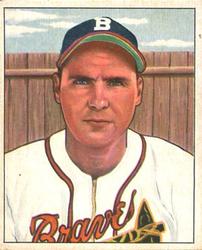

Tommy Holmes

A severe sinus condition kept Tommy Holmes out of the service during World War II, but the chances are that if he had been drafted and sent into harm’s way, several hundred fans from one particular portion of Braves Field would have been willing to follow him into action.

A severe sinus condition kept Tommy Holmes out of the service during World War II, but the chances are that if he had been drafted and sent into harm’s way, several hundred fans from one particular portion of Braves Field would have been willing to follow him into action.

Holmes was among the most popular performers in Boston baseball history, and during his career with the Braves, from 1942 to 1952, nobody enjoyed the type of unabashed love he received from the denizens of the 1,500-seat, stand-alone bleachers situated behind his right-field playing spot. Dubbed the Jury Box by a sportswriter who once counted just 12 fans seated there in leaner times, the section with its wooden benches was filled during the club’s contending years with a crew of regulars who developed a friendly give-and-take with their hero. “How many hits you gonna get today, Tommy?” a patron might yell, and Holmes would shout back a reply or hold up however many fingers he deemed appropriate. There is no record of his accuracy in forecasting, but the Pride of the Jury Box had plenty of clutch blows at the ballpark — none bigger than his eighth-inning single off Bob Feller that gave the Braves a 1-0 victory in the opening game of the 1948 World Series.

A .302 lifetime hitter who set a then-National League record with a 37-game hitting streak in 1945 and was one of the toughest men in history to strike out, Thomas Francis Holmes was born on March 29, 1917, in the Borough Park neighborhood of Brooklyn. One of eight children, known as “Kelly” to his pals, he had a round, ruggedly handsome face and a chunky, 5-foot-10 frame that didn’t seem to match his high-pitched Flatbush Irish accent. Dreaming in his early years of being a boxer, he was dubbed “the world’s champion juvenile bag-puncher” at the age of 5 and won many prizes in this area through grade school. The rejection of such pugilist hopes by his father (who had been a second for several prizefighters himself) prompted Tommy to focus on baseball as a teenager.

In discussing his early diamond development, the left-handed Holmes always credited Brooklyn Technical High coach Anthony Tarrantino as his first great teacher. “He was the John McGraw of the high schools,” he said of Tarrantino, under whose tutelage he hit .613 as a senior in 1935. “In the winter months he used to have me eat my lunch up in the gymnasium. He would draw home plate on the floor, and then we would talk about hitting. He’d show me parts of the plate, zoning and so forth. He was telling me how to reach the outside of the plate, how to reach the inside, and what to look for from a pitcher. He also taught me to have the courage to hit to opposite fields.”

When Tech played Tilden High for the city championship, Holmes remembered Tarrantino shouting out, “There’s the best ballplayer in Brooklyn!” when Tommy got a hit. Since Tilden’s lineup included a standout named Sid Gordon who also enjoyed a successful big-league career, such praise meant a lot to Holmes. The confidence his coach instilled in him served Tommy well in the competitive semipro ranks of New York City baseball. “We grew up playing ball, or watching it, all the time,” Holmes recalled. “Right in Brooklyn we had the Parade Grounds, which had about 21 fields. One big half-mile square filled with diamonds, and we played there every Sunday.

“I was a Dodgers fan growing up, but I never hated the Yankees. Many times three of us would get 55 cents together, we’d go over to Ebbets Field, and one kid would go through the turnstile and the other two would sneak under after him. I’d get to see a ballgame for under 20 cents. Then there was the Happy Felton program. He was a radio broadcaster who would get the Dodgers ballplayers to come out, and the kids would ask them questions. Then the players would put on kind of a clinic.”

Brooklyn had two semipro teams that drew the attention of major-league scouts, the Bay Parkways and the Bushwicks. After graduating from high school, Holmes went seeking a job with the Bay Parkways. “Harry Hess, the manager, told me I was just a kid, but then one day a guy didn’t show up and he said, ‘Can you play left field?’ I said sure, even though I had never played left field in my life. I was a first baseman. Well, I got a couple hits, and the next Tuesday night an owner of the Bushwicks — there were two brothers, Joe and Max Rosner, who owned both clubs — he called and asked me if I would play at Dexter Park for him against Josh Gibson, Satchel Paige, and all of those great Negro League players. I told him sure. I batted against Satchel Paige; I didn’t know who he was, but I got a couple of hits.” (Although Holmes never mentioned it to this writer, many sources claim he also played for the Bushwicks while still in high school, under the assumed name Thomas Kelly.)

Watching the games in which Holmes suited up against Gibson and Paige’s Pittsburgh Crawfords team was Yankees scout Paul Krichell. He called Tommy’s father, and as Holmes recalled, “There were no negotiations. We got together, Krichell said ‘We’d like to sign your son,’ and they gave me a few bucks — not much. I don’t even remember what my bonus was. My father just said, ‘Sure, sounds good.’ I stayed out of the financial end of it. The average, I think, was $500 for a kid like me coming out of high school, and maybe $1,000 or a little more for a college kid with three or four more years’ experience.”

It was the late 1930s, and the Yankee dynasty started by Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig was continuing with Gehrig, Joe DiMaggio, Bill Dickey, and Co. New York would win four consecutive World Series from 1936 to 1939, and the club oozed with confidence. “The Yankees always won, and they had no signs,” Holmes said. “When I went to spring training with them, I asked what the signs were, and guys would say ‘Signs? Just swing the goddamn bat!’ I’d say, ‘Well, what about….’ and they would yell, ‘Just swing the bat! If we can hold the opposition to four runs, we’ll score seven.’ That was the Yankees — bang-bang-bang. They had the power, and they could beat the hell out of you.

“I was told by George Weiss, then the Yankees’ farm director, that their philosophy was that hopefully you had three years of playing Triple A ball, or at least two years. I could have come up earlier, but with DiMaggio, [Charlie] Keller, and later [Tommy] Henrich in the outfield, it was tough. Weiss said to me, ‘Tommy, don’t you sit around. You go out and play.’ Holmes did as he was told, and put up great numbers. During his first professional season at Norfolk, in the summer of ’37, the center fielder batted .320 with 25 homers and 111 RBIs. He made the All-Star team that year, then followed it up with an MVP campaign in ’38 when he led the Eastern League with a .368 average, 200 hits, 41 doubles, and 110 runs for the Binghamton Triplets.

This prompted a promotion to the Yankees’ top farm club, the Newark Bears — a team then considered to be the equal of many major league squads. All Holmes did there was bat .339 with 10 triples in 1939. His power numbers were down (he had just four homers, and topped 13 just once more as a pro), but it was clear that he was a first-rate hitter. Things progressed further in 1940, as Tommy topped the International League with 211 hits and 126 runs scored while batting .317. He was even better in the playoffs, setting a circuit mark for postseason hits and helping lead Newark to the Little World Series title. On September 13 of that year, the Associated Press reported that Dodgers president Larry MacPhail had supposedly offered the Yankees $40,000 for the hometown hero, but this was never substantiated and Holmes stayed put.

By the end of spring training in 1941, having just turned 24 and married his sweetheart, Lillian Helen Pettersen, Holmes was already a veteran of four minor-league seasons, who had shown the talent that normally warranted a promotion to the majors. But Keller, DiMaggio, and Henrich were still manning the outfield for the Bronx Bombers — with reigning AL batting champ DiMaggio in Tommy’s position of center — and that left little room for a rookie lacking home run prowess. So after a look-see in spring training, Yanks manager Joe McCarthy sent the youngster back to Newark yet again with a promise: If New York couldn’t find a space for him on its roster during the regular season, club management would make every attempt to grant his wish and send him to another big-league organization.

McCarthy was true to his word. Holmes hit .302 with a league-best 190 hits in his third season for the Bears in ’41, but with the Yankees’ outfield contingent seemingly set for years to come, the organization decided to trade off its still-valuable prospect. Two days after the Pearl Harbor attack, on December 9, 1941, Holmes was sold to the Braves for undisclosed cash and players to be named. The Yanks received first baseman Buddy Hassett a week later as part of the deal, and on February 5, 1942, Boston outfielder Gene Moore was sent Bronx-bound to complete it. The trade still ranks as one of the finest in Braves history; while Hassett played just one more season in the majors and Moore three subpar campaigns, Holmes was among the NL’s top hitters for much of the next decade. “I always said it took the best ballplayer in the world — Joe DiMaggio — to run me out of New York,” Tommy said, and while he was kidding, there was much truth to the statement.

With a tight budget, a no-frills ballpark, and a club mired deep in the second division, the Braves were the polar opposites of the aristocratic Yankees. Boston was coming off a 62-92 season and a third straight year in seventh place under manager Casey Stengel, and Tommy instantly found himself with a starting center-field job for 1942. Later he recalled that when he asked Stengel, “Who in God’s name brought me here?” Casey said simply, “I did. Someday I want to build a whole ballclub around you.” Holmes called going from the Yankees organization to the Braves like “living at the Waldorf, then going to live in Povertyville down at the Bowery.”

Pearl Harbor and America’s entry into World War II made for a long winter, but Holmes was still all smiles come spring. When the Braves started their season at Philadelphia on April 14, Tommy donned jersey No. 1 (which he’d wear his entire career) and batted leadoff in his major-league debut — going 2-for-5 against future teammate Si Johnson in a 2-1 Boston victory. And although the Braves wound up seventh yet again under Stengel, there were two future Hall of Famers on the playing roster all year for the rookie to learn from. Slow-footed catcher Ernie Lombardi hit .330 to capture the league batting title, and former Pirates great Paul “Big Poison” Waner played alongside Holmes in right field. Just a .258 hitter at age 39, Waner still had the knowledge of a man with three batting titles and a lifetime average of .330-plus under his belt. When he collected his 3,000th hit that year during his one full season with Boston, he was just the seventh big leaguer to achieve the feat.

For Holmes, Waner was nothing short of a revelation. Big Poison preached pulling the ball to right field, and in this curious rookie he had an apt pupil. “One day in ’42, I took an 0-for-9 in a doubleheader,” Tommy recalled nearly 60 years later. “I was in the clubhouse moping around, and there was Paul Waner, who liked his sauce, having a beer. He says, ‘What’s the matter, kid?’ I say, ‘Paul, I was 0-for-9 today.’ He says, ‘Don’t worry about that. Just come out in the morning.’ This was the beginning of my hitting life. I was a line-drive hitter, same as Paul. He says, ‘See that foul line over there? I’m going to show you how to hit it. Never hit the ball where three guys can catch it, not with that wind blowing in at Braves Field. Shoot for the foul lines. If a few go out of play, don’t worry about it. You don’t pay for the balls.’” (Although Holmes credited Stengel with similar batting tips at the time, he always cited Waner as his chief tutor in later interviews.)

The rookie learned his lessons well. Batting leadoff most of the year, Holmes hit .278, second only to Lombardi among Boston’s regulars, and struck out just 10 times in 558 at-bats. He went 10-for-19 in one August stretch against the Dodgers and Giants, broke up two no-hit attempts, and compiled a .990 fielding average to tie for second best in the league. Having not gotten his first big-league shot until he was 25 years old, he was making up for lost time. Even when he dipped a bit to .270 in his sophomore season, he led the league with 629 at-bats and collected 33 doubles and 10 triples. He was above .300 much of the season, often batted third, and later claimed that focusing on learning to pull the ball cost him 50 points in his batting average. It proved a worthwhile sacrifice.

Of course Tommy’s mind was likely on more than baseball that summer. With the war in Europe and Japan heating up, married players like Holmes were starting to be drafted, and he got a call in March 1944 to leave spring training and report to Brooklyn for his Navy physical. Although it was widely reported that he had passed and would be reporting for duty that summer, the call never came. Later, Holmes described an induction scene where examining doctors determined him unfit for duty due to lifelong sinus problems that they feared could be life-threatening in the European climate.

One of a dwindling number of strong young ballplayers left on big-league rosters, and fresh off a winter spent working in the Brooklyn shipyards, Holmes posted his first super season in 1944. Third in the NL with 195 hits, 93 runs scored, and 42 doubles, he also finished 10th in hitting at .309 after staying near the top (and above .330) into late summer. His power totals took a big leap as well: after hitting four and five homers in his first two years in the majors, he slugged 13 — ninth in the league. The introduction of the wartime “Balata ball” had hampered slugging league-wide, but Holmes hit the heavier spheres better than most.

Making the feat more impressive was the ballpark Tommy called home. Braves Field was a cavernous park built during the inside baseball era of 1915, just before Babe Ruth ushered in the home run age. Its center-field fence was originally built 550 feet from home plate, and with the wind blowing in off the Charles River just beyond its walls, few on the club had ever managed even 20 homers. Now, seeing that Holmes had some pop in his bat, Braves management brought the 345-foot right-field fences in by 20 feet midway through the ’44 campaign to give him an easier target.

Even with this move, what transpired next took the most optimistic of fans by surprise. Holmes got off to a hot start in 1945 that never let up, and Paul Waner’s star pupil reached his peak. Although the Braves stumbled to yet another second-division finish, Tommy astonished the baseball world by leading the major leagues with 28 homers, 224 hits, 47 doubles, a .577 slugging percentage, 81 extra-base hits, and 367 total bases. He batted .352 — finishing second in the NL to Phil Cavarretta of the Cubs in a race that went down to the final day — and was also runner-up (to Brooklyn’s Dixie Walker) with 117 RBIs. His 125 runs scored placed him third in that department, and he even stole 15 bases (fourth most in the NL) for good measure. Moved to right field to make room for Carden Gillenwater in center, Holmes played in all 154 games and had 13 assists, to the delight of the Jury Box fans now seated just behind him. (Tommy’s throwing arm was never considered a strong suit, but he did manage 10 or more assists in seven seasons.)

Making this dominant showing all the more impressive was what Holmes did in the middle of it — establishing a new NL record with a 37-game hitting streak. He started the stretch in scorching fashion with 10 total hits in back-to-back doubleheaders on June 6-7, and kept up the torrid pace into July. He tied and broke Rogers Hornsby’s old mark of 33 straight games against the Pirates in another doubleheader that featured rainy, hurricane-like conditions at Braves Field and a homer, single, and four doubles by the man of the hour.

The hits kept coming right up until the All-Star break (which he entered with a major-league-best .401 average), but in his first game after the three-day layoff, Holmes was stopped by Hank Wyse of the Cubs on July 12 at Wrigley Field. All told, he batted .433 during the streak, which lasted as a record for 33 years before being broken by Pete Rose. Even today, while Tommy’s breakthrough season has been largely (and unfairly) forgotten by all but fervent baseball historians, his hitting streak still stands as the ninth longest in big-league annals.

Perhaps the most amazing stat of all is that Holmes stepped to the plate on more than 700 occasions in 1945 (636 official at-bats plus 70 walks) and left it a strikeout victim just nine times (once swinging). This gave him the distinction of being the first man ever to lead the majors in most homers and fewest strikeouts in the same season, an incredible display of contact hitting in keeping with his career averages. Holmes never struck out more than 20 times in a season, and had more homers than strikeouts on a record-tying four occasions (Ernie Lombardi, Lefty O’Doul, and Ted Williams also accomplished this feat). In fact, Holmes’ 122 lifetime strikeouts in 4,992 career at-bats are fewer than many current major leaguers notch in just one season of less than 600 at-bats.

Unfortunately for Holmes and his fans, Tommy’s breakthrough summer did not end with a National League MVP award. That honor went to Cavarretta of the pennant-winning Cubs, who despite edging Holmes for the batting crown finished far behind him in every other major offensive category. The native Chicagoan hit just six home runs, missed 22 games with assorted injuries, and as a first baseman did not hold down a crucial defensive position. Still, perhaps overly influenced by the finishes of the Cubs and the sixth-place Braves, writers gave Cavarretta 15 first-place votes to second-place Tommy’s three. Holmes was named Player of the Year by The Sporting News and Boston sportswriters, however, and the team’s management and fans chipped in to buy him a new Packard automobile in a Tommy Holmes Day ceremony at Braves Field on September 2. He celebrated, naturally, by slugging a home run.

With Holmes established as a top star by the end of ’45, new Braves president Lou Perini and his ownership group began following through on Stengel’s dream of surrounding Tommy with a strong team. Ace manager Billy Southworth (a three-time pennant winner) was brought in from the St. Louis Cardinals, and the war’s end along with blockbuster trades brought many new faces onto the 1946 roster, including Warren Spahn, Johnny Sain, and Johnny Hopp. The result was a leap to third place, and Holmes had another standout season with a .310 average, 35 doubles, and a 20-game hit streak. The Jury Box crowd so adored him that when Tommy swapped positions with left fielder Johnny Barrett for one day that year, fans showered Barrett with so many boos and insults that he claimed at game’s end, “I’ll never go out there again.” There was one problem, however. “The owners had doubled my salary to around $30,000 [after ’45],” Holmes recalled later, “but then they went and moved the fences back out!” Despite Tommy’s 28 home runs and teammate Chuck Workman’s 25 during 1945, team statisticians saw that more opponents than Braves sluggers had been taking advantage of the closer right-field target. When the fences went back out, the result was just six homers and 79 RBIs for Holmes in ’46. The Pride of the Jury Box would never crack as many as 10 homers again, but Perini and Co. were finding other big bats to do the bashing.

Bob Elliott came on the scene in 1947 and in addition to crushing 22 homers finished just ahead of Holmes in the National League batting race, their .317 and .309 marks placing them in second and seventh place respectively. Tommy’s 191 hits topped league MVP Elliott and the rest of the senior circuit, and one of his rare home runs was particularly meaningful — a ninth-inning shot to beat the Giants on August 10, the day his son, Tommy Jr., was born. “I couldn’t let the kid think his old man didn’t have it in the clutch, could I?” Holmes quipped to sportswriters. (Tommy Jr. later appeared with his dad in a full-color magazine ad for Wheaties.)

Everything came together for the Braves in 1948, and Holmes was a big factor as leadoff man for the NL champions. He placed third in the league with a .325 average (his fifth straight year in the top 10), was second with 190 hits, and made his second All-Star team. The Three Troubadours, a trio of musicians who serenaded players at Braves Field on trombone, trumpet, and clarinet, played the Irish tune “Has Anybody Here Seen Kelly?” when Holmes stepped to the plate. The answer was more folks than ever, as the Braves set an all-time attendance mark of 1,455,439 that summer even as the Red Sox were drawing 1,558,798 of their own while battling for an American League pennant down the road.

And although Holmes batted just .192 in the World Series against Cleveland, he had arguably the biggest hit of the fall classic. With Johnny Sain and Bob Feller locked up in a scoreless pitchers’ duel in the eighth inning of Game One at Braves Field, Tommy’s roommate, Phil Masi, appeared to be caught snoozing off second base when Feller and Cleveland shortstop Lou Boudreau pulled a pickoff play they had been practicing. It was clear in still photographs taken at a variety of angles that Boudreau had indeed tagged Masi on the shoulder before he could slide back into the bag, but umpire Bill Stewart (a Fitchburg, Mass., native) saw it differently and called Masi safe. Sain lined out, but then Holmes hit a ball past Ken Keltner at third to drive in Masi with the game’s only run and send the chilly home crowd of 40,135 into a frenzy. Feller wound up a 1-0 loser despite his two-hitter, and the Braves had a quick edge in the World Series. It was a heady time for the underdogs, but it was short-lived. Boston went on to drop four of the next five games and the series, with Holmes ending the 4-3, Game Six finale at Braves Field with a fly out. As if this wasn’t bad enough, Tommy had to head to the hospital the next day for an appendectomy. Then it was back to Brooklyn for his newest offseason job — selling televisions.

Braves management was confident that their team could contend for years to come, but in 1949 the Braves quickly fell back to fourth place. Talk of dissension rocked the club starting in spring training, as players reportedly grumbled about Southworth driving them too hard and seeking too much credit for the previous year’s accomplishments. Players later said the disharmony was largely a figment of the press, but there was no denying the dramatic decline in performance by many on the club. Holmes was among them; he batted less than .300 for the first time in six years (dropping all the way to .266), and began getting platooned on a semi-regular basis. He got his average back up to .298 in 1950, when the Braves again contended much of the season, but by then Tommy was practically splitting time with Willard Marshall. Even though Holmes showed a bit of his 1945 pop with nine homers in just 322 at-bats, his playing career was winding down. The organization had other things in mind for him.

As a player Holmes was popular with his teammates, the coaching staff, fans, and reporters, so it seemed only natural that he might make a success as a manager. He was asked to take over the Braves’ farm club at Hartford as player-manager for the 1951 season, and he enthusiastically accepted the challenge. By midway through the year Billy Southworth’s health and the big league team’s record were both floundering, and with Southworth’s stunning resignation on June 19, another request came Holmes’ way: How would he like to manage in Boston? He had likely thought it would be years before such an opportunity came, so it was no surprise that Tommy again said yes.

In many ways, his appointment — which also cost Hartford Holmes’ .319 bat — was an experiment doomed to fail. Suddenly the youngest skipper in the big leagues at just 34, Tommy took over an underachieving club mixed with veterans like Elliott, Spahn, and Earl Torgeson who had been his teammates the previous year, and raw youngsters like Johnny Logan and Chet Nichols who were getting their first taste of the majors. It was hard for him to establish authority under such circumstances, and his mild-mannered approach and lack of training didn’t help. While there were some high points, including a 9-0 victory by Spahn over the Cubs in Holmes’ managerial debut and a midsummer stretch in which the club won 14 of 18 games, by year’s end his record was a mediocre 48-47 for a team that finished 76-78 overall.

The worst was yet to come. In 1952 the Braves got off to a poor start, and Tommy (cover boy on the first edition of the team scorebook that season) became a convenient scapegoat. Newspaper columnists who had spent a decade praising his playing skills now attacked his tactical moves and coaching prowess at third base, and on May 31, with the club in seventh place at 13-22, he was fired in favor of Charlie Grimm — whose managerial résumé already included 13 big-league seasons and three pennants. General manager John Quinn said Holmes simply needed more experience to be a successful skipper, an odd comment considering that he now had a year more of it than when they had given him the job.

Asked his own feelings, the ever-classy Holmes said of the club that fired him by phone: “They are wonderful people. They probably hated twice as much telling me I was fired as I disliked hearing it. And it’s no disgrace to be replaced by Charlie Grimm.” In later years he would be more open, telling the Boston Herald in 1986: “It broke my heart when they let me go. I was ready to have a home built up there. That was going to be my home. It was a shock. It was like losing your family. I don’t think I ever got over that even yet.”

In the end, there was a bright spot to the season for Tommy. He signed on two weeks later as a spare outfielder with his hometown Brooklyn Dodgers, and on June 29 he beat the Braves with a pinch single before Boston’s second biggest home crowd of the season (13,405). Brooklyn wound up winning the pennant, and Holmes saw his last big-league playing time in a seven-game World Series loss to the Yankees. The Braves meanwhile, finished with a 64-89 record and back in seventh place. Attendance had fallen to 281,000, financial losses were mounting, and the following spring Perini announced he was moving the club to Milwaukee. The Jury Box fell silent.

Although it frustrated his fans that Tommy didn’t get a chance to stick as manager long enough to help the Braves flourish after their move — they leaped to 92 wins in 1953, and claimed a World Series title over the Yankees by 1957 — in retrospect his exit while the club was still situated in New England seems appropriate. Perhaps more than any other player, Holmes personified the underdog, determined Boston Braves. And despite how his career with the team ended, his numbers still shine through. He averaged 185 hits, 36 doubles, and 86 runs scored during his nine seasons as a regular, and ranked among baseball’s Top 10 during the 1940s in hits and doubles.

His playing career in the majors now finished once and for all, Holmes embarked on a minor-league managerial odyssey during the next several seasons. Lou Perini brought him back to the Braves organization to lead its top farm club in Toledo for 1953, after which he jumped once more to Brooklyn as skipper of its Class A team at Elmira for ’54. He summered with Fort Worth of the Texas League in 1955, and with the Portland Beavers of the Pacific Coast League the next year. In ’57 he returned home once more to scout New York area high school and college players for the Dodgers, but then later that summer was off to Montreal to manage the Royals of the International League.

Tommy’s travels finally stopped in 1959. He was named director of the New York Journal-American’s sandlot baseball program, which was later renamed the New York Sandlot Baseball Alliance. (His former mentor Paul Waner had once held the job.) In more than 30 years in this position, Holmes would help teach thousands of youngsters, many from underprivileged backgrounds, the joys of the game. He once claimed that 85 of “my kids” had made the major leagues, and said with pride that “none of my kids, no matter what their ability, sits on the bench.”

Starting in 1973, Holmes took on an additional role as director of amateur baseball relations for the New York Mets. He became a familiar figure around Shea Stadium during three decades on the job, but likely never would have risen from relative obscurity outside Flushing Meadows had not Pete Rose gotten on a hot streak during the summer of 1978. Once Rose had hit in 30 straight games and was nearing Holmes’s record 37-game skein, Tommy’s name started appearing in newspaper stories throughout the country for the first time in a quarter-century. “I wish [Rose] luck,” Holmes joked to a reporter. “Heck, until two weeks ago nobody knew I was alive.”

As fate would have it, the Reds were playing at Shea against the Mets when Rose reached game No. 38 of his streak on July 25. The game was stopped momentarily to honor the achievement, and a teary-eyed Holmes stepped on the field to shake the new record-holder’s hand. The gesture impressed Rose, who said of his predecessor, “I only hope I show as much class as Tommy Holmes did when somebody breaks my record. He thanked me for making him a big leaguer again.” (Rose eventually made it to 44 games before he was stopped, ironically, by the Atlanta Braves.)

Ten years later, when the ’48 Braves were invited back to Boston for a 40th reunion, one of the most popular guests was a still-trim Holmes — sporting his 1986 World Series championship ring earned with the Mets at the expense of the Red Sox. He and his beloved Lillian also made the drive up from their home in Woodbury, Long Island, each year throughout the 1990s to attend the annual events hosted by the Boston Braves Historical Association (BBHA), where he delighted in talking about Waner, Stengel, and other departed colleagues while meeting with fans who had cheered him from the Jury Box half a century before. Holmes was the inaugural inductee into the BBHA’s Boston Braves Hall of Fame at the 1993 event ; another dinner featured a reunion of Holmes and Bob Feller — who ribbed each other about Game One of the ’48 World Series a half-century after the fact. When an original member of the “Three Troubadours” surprised Tommy at one reunion with his clarinet rendition of “Has Anybody Here Seen Kelly?” it brought tears to the old right fielder’s eyes.

When ill health prompted Tommy’s retirement from the Mets and stopped his pilgrimages to the Hub around 2002, it was if the Braves diehards who remained were losing their hero all over again. Holmes no doubt felt the same way. He always said it was not the batting streak or his hit off Feller that provided him with his greatest Boston memories; those were reserved for his love affair with the 1,500 bleacherites in right field. “Williams, DiMaggio, Musial — they never had what I did,” he often recounted proudly. “The other 29,000 fans, if they wanted to give me a boo or two, go ahead. But not if you sat behind me in the Jury Box, I’ll tell you that. They were always hollering at me, ‘Keep your eye on the ball, Tommy!’ ‘Try and wait for a good one, Tommy!’ Tommy this, and Tommy that.

“I remember when I was on the 28th game of my streak. It was a beautiful day; the sun was all over the place. And this gentleman comes into the Jury Box under the influence of liquor, and starts in on me: ‘So you’re the great Holmes! You couldn’t carry Ted Williams’ jock!’ Then of course I get up and hit into a double play. Holy geez. So now I go back out to right, and he yells, ‘If I wanted to go to the circus, I would have gone to the GAAAH-DEN!’ Finally, Marty Marion hits a line drive to me with the bases loaded: ‘I have it, I have it, I have it.… I can’t find it.’ It hits the fence behind me, and the guy yells, ‘Now I KNOW I’m going to go to the GAAH-DEN, because I have never seen anything like this!’”

Just then, a little fellow in the front row behind me says, ‘Tommy, I’m going to take care of this.’ He goes and gets Big Dan, the Irish cop. Now you can’t arrest a fan for yelling or cursing, but remember, he was needling me about Williams and so on and so forth. I come out the next inning, and the loudmouth is gone. I say ‘What happened?’ And the little guy says, ‘We had Big Dan throw him out of the ballpark!’

“That’s the way it was out there. They would do practically anything for me, and I never forgot it.”

The Pride of the Jury Box still had his original Boston Braves uniform, socks, and cap when he died of natural causes on April 14, 2008, at the age of 91. His passing in Boca Raton, Florida, left Al Dark as the last regular from the 1948 National League championship club still alive, as fellow teammates Sain, Spahn, Eddie Stanky, and Bill Voiselle had all died in recent years. Tommy had also been the last living Boston Braves manager for quite some time, owing to the young age at which he held the position.

In tributes that appeared in newspapers upon his death, Holmes’ good-guy image shined through. His daughter, Patricia Stone, said her father had been enjoying baseball games on television right up until the end. She also recounted that “When he played baseball, there would be days he’d leave early and he’d pass children playing and he’d stop to play with them.” Son Tommy Jr. said that “he loved every minute of his time in Boston and he received fan mail long after he left.” Those family members mourning his loss also included his beloved wife of 67 years, Lillian, two grandchildren, and two great-grandchildren.

Mets Chief Operating Officer Jeff Wilpon called his former employee “one of our sport’s truest gentlemen,” adding that “his passion for the game and up-and-coming players, along with his 30-year association with our franchise, was unsurpassed.” So was his passion for hitting, as evidenced by a story told to the New York Daily News by Mets employee Lorraine Hamilton — one of several female front office employees who played on the organization’s softball team and received valuable advice from Holmes. “He told me, ‘Anyone can hit if they put their mind to it’ and he worked with me in the batting cages.” What Hamilton probably didn’t realize is that she was getting a variation on the same sage advice Paul Waner had once passed down to Tommy at Braves Field so many years before.

Those players still around who played with or for Tommy were just as praising. “He always made rookies like myself and Johnny Antonelli feel like one of the guys,” said catcher Del Crandall, a teammate in 1949 and ’50. “He was a real pro the way he went about his business, and when I played in Milwaukee, I inherited his uniform No. 1.”

Tommy Holmes — No. 1 in your (old) scorebook, and No. 1 in the hearts of Boston Braves fans.

Note

This biography originally appeared in the book Spahn, Sain, and Teddy Ballgame: Boston’s (almost) Perfect Baseball Summer of 1948, edited by Bill Nowlin and published by Rounder Books in 2008.

Sources

Author interviews with Tommy Holmes, 1991-2002

Tommy Holmes remarks at Boston Braves reunions, 1991-2002

Assorted Associated Press, New York Times, and Hartford Courant articles, 1939-1978

“Home of the Braves,” Boston Herald Sunday Magazine, May 4, 1986

Kaese, Harold, “Boston’s Strong Boy,” Sports World, July 1949

Pave, Marvin, Holmes obituary in Boston Globe, April 15, 2008

Rubin, Roger, Holmes obituary in New York Daily News, April 15, 2008

Caruso, Gary, The Braves Encyclopedia, Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1993.

Kaese, Harold, The Boston Braves, New York: G. P. Putman’s Sons, 1948

Honig, Donald, Baseball Between the Lines, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1976

Photo Credit

The Topps Company

Full Name

Thomas Francis Holmes

Born

March 29, 1917 at Brooklyn, NY (USA)

Died

April 14, 2008 at Boca Raton, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.