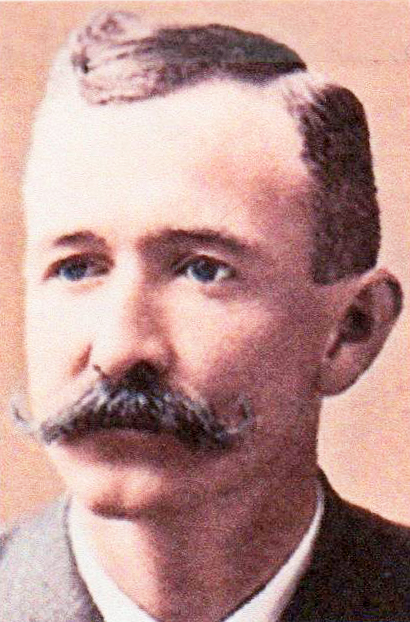

Bill Watkins

Prominent in the baseball circles of his time but now forgotten, Bill Watkins spent more than thirty years as a player, manager, front office executive, and team owner of various major and high minor league franchises. His playing career short-circuited by a near fatal beaning in 1884, Watkins thereafter assumed the manager’s post for the Detroit Wolverines and within three years, transformed that National League doormat into the baseball world champions of 1887. During his heyday, however, Watkins was most often associated with Indianapolis, serving no fewer than eight baseball organizations established in the Indiana capital. Finally leaving the diamond scene in the early 1920s, Watkins — a Canadian by birth — spent his remaining years as the leading citizen of Marysville, Michigan, a suburban Great Lakes community that Watkins himself helped to found.

Prominent in the baseball circles of his time but now forgotten, Bill Watkins spent more than thirty years as a player, manager, front office executive, and team owner of various major and high minor league franchises. His playing career short-circuited by a near fatal beaning in 1884, Watkins thereafter assumed the manager’s post for the Detroit Wolverines and within three years, transformed that National League doormat into the baseball world champions of 1887. During his heyday, however, Watkins was most often associated with Indianapolis, serving no fewer than eight baseball organizations established in the Indiana capital. Finally leaving the diamond scene in the early 1920s, Watkins — a Canadian by birth — spent his remaining years as the leading citizen of Marysville, Michigan, a suburban Great Lakes community that Watkins himself helped to found.

The long and productive life of William Harton Thomas Watkins began in Brantford, Ontario on May 5, 1858.1 Bill was the second of five children born to John Luke Harton Watkins (1824-1915), a farmer- turned-prosperous-dry goods merchant, and his wife, the former Eliza Jane Tyler (1834-1868).2 Both parents were Canadian, descended of Irish Protestant stock. Bill’s youth was unsettled by the untimely death of his mother in 1868. He was then sent to the rural enclave of Erin to be raised by his maternal grandparents.3 Bright and with mechanical aptitude, Watkins was educated at local prep schools and then spent a year at Upper Canada College, a prestigious post-graduate school located in Toronto. During his school years, Watkins was introduced to baseball, his interest in the game developing as he began his working life as an apprentice in a novelty machine manufacturing plant. Thereafter, he was employed by a Canadian branch of the Ingles-Corliss Engine Works.4 Watkins emigrated in 1879, taking up residence in Port Huron, Michigan, the Great Lakes city that he would call home for the next forty years.5

Demonstrating leadership qualities from an early age, Watkins began his baseball career in 1880 as the youthful playing manager of the Maple Leafs of Guelph, Ontario, a nearby semipro nine.6 The following year, he moved up a competitive notch, steering the St. Thomas Atlantics, one of Canada’s top semipro clubs. Thereafter, Watkins took command of his new hometown’s side, piloting the Port Huron club to the Michigan State League championship in 1882 and 1883. The following year, Watkins entered the professional ranks, taking the post of second baseman/manager of Bay City in the minor Northwestern League. Watkins had his latest team in pennant contention (37-14, .726) when financial difficulties precipitated the dissolution of the Bay City franchise in early July 1884. Despite posting only a .234 batting average, Watkins had caught the eye of those in charge of even faster competition, preserving his career in baseball.

With three professional operations — National League, American Association, and Union Association — all claiming major league status, the 1884 season supplied ample employment opportunities for unattached ballplayers, even those with only marginal playing ability. Bill Watkins, now 26, was among their number. In late July, he signed a contract to play for the woeful Indianapolis Hoosiers of the 12-club American Association. Then a lean 5’10”/156 lb., the right-handed Watkins7 was immediately inserted into the Hoosier lineup at third base and went 1-for-4 in his August 1 major league debut, a 7-6 loss to Columbus. Ten days later, the rookie infielder was given charge of Indianapolis fortunes, replacing Jim Gifford at the helm of the 25-60, eleventh-place team. Once in charge, Watkins switched himself to second base and “played his position nicely.”8 He also began to show some pop at the plate, going 9-23 (.391) over a six-game stretch. On August 26, however, an errant first inning fastball by Cincinnati fireballer Gus Shallix effectively ended the playing career, and almost took the life, of Bill Watkins. Struck squarely in the head by the pitch, Watkins spent the next several days in and out of a coma before recovering.9 On September 11, Watkins was able to place himself back in the Hoosiers lineup, going 2-for-4 at the plate while handling six chances cleanly at second base. But it soon became obvious that he was not the player he had been before the beaning. In his last 12 games, Watkins went 3-for-37 (.081) with the bat and played erratically in the field. And by season’s end, Watkins had benched himself. The Hoosiers joined their skipper in the performance tailspin, losing their last 13 games in a row and finalizing the Watkins managerial log at a dismal 4-18 (.182) for the next-to-last-place Indianapolis club. That fall, the American Association dropped the Indianapolis franchise.

Like the defunct Hoosiers, Bill Watkins never played another major league game. In his 133 lifetime plate appearances, Watkins had batted an anemic .205, with only four extra-base hits. In the field, he had been no better, posting a substandard .878 fielding percentage between second, third, and two games at shortstop. But if Watkins’ ball playing career was behind him at an early age, two lifelong endeavors beckoned. On November 6, 1884, Watkins married Edna Buzzard, the daughter of a Port Huron sea captain. The Watkins marriage would endure for the next 52 years, but apparently without children. Three months after marrying, Watkins commenced his tenure as a fulltime baseball executive, joining Ted Sullivan, Tom Loftus, and George Tebeau in organizing the Western League, a new minor league circuit composed of teams located in six mid-sized Midwestern cities. Watkins himself took command of the league’s Indianapolis entry, a team which retained the Hoosiers nickname but otherwise bore little resemblance to its hapless AA predecessors. This new Indianapolis nine quickly took a commanding lead in the inaugural WL pennant chase. Then on July 6, 1885, the first-place (27-4) Hoosiers franchise failed financially, precipitating the immediate demise of the new league. Shortly thereafter, the assets of the Indianapolis franchise, including the contracts of manager Watkins and star outfielder Sam Thompson, were purchased by the Detroit Wolverines of the National League.

With Detroit (7-31) hopelessly out of pennant contention, Watkins replaced Charlie Morton as Wolverines manager. In keeping with nineteenth century norms, on-field decisions — batting order, defensive alignment, in-game stratagems, and the like — remained the province of Wolverines team captain and centerfielder Ned Hanlon. Watkins served as a one-man front office, attending to administrative chores like player acquisition, travelling/hotel accommodations, collection of gate receipts, and the scheduling of exhibition games, an important revenue source for the financially shaky Detroit franchise. Watkins, something of a martinet as a younger man, also attended to team discipline, doling out $10 fines for shoddy play in the field and leveling more substantial penalties for late-night carousing, a common player pastime that Watkins could not abide. Under the Watkins regime, the Wolverines made progress, finishing the 1885 campaign at 41-67 and positioned for advancement in league standings.

The 1886 season would prove an eventful one for Bill Watkins. The previous winter, pharmaceutical manufacturer/sportsman Frederick K. Stearns had assumed the presidency of the Detroit club and was determined to transform the Wolverines into a championship nine. To that end, Stearns purchased the defunct Buffalo franchise, and with it, the contracts of the club’s famed Big Four: Dan Brouthers, Deacon White, Hardy Richardson, and Jack Rowe. Once in uniform, the group elevated Detroit into an immediate pennant contender. Then at mid-season, Watkins came to terms with crack second baseman Fred Dunlap, late of the St. Louis Maroons — the first in a series of events that would earn Watkins the enmity of Mound City partisans.10 Paced by the offense supplied by Brouthers (.370), Richardson (.351), and Sam Thompson (.310), and with Lady Baldwin and Pretzels Getzien combing for 72 wins from the pitcher’s box, the Wolverines’ record skyrocketed to 87-36 (.707). But that sterling performance was good only for second place, three games to the rear of the NL pennant-winning Chicago White Stockings of Cap Anson/King Kelly/John Clarkson fame.

During the offseason, controversy arose from Watkins attendance at the American Association winter meeting, a gathering focused on the crisis created by the jump of the Pittsburgh club to the National League. When quizzed about Detroit’s intentions, Watkins played it coy, neither confirming nor denying Detroit’s interest in transferring to the AA. Thereafter, following long-distance consultation with Stearns, Watkins announced that the NL had granted the concessions sought by Detroit and withdrew himself from the AA conclave. This proved too much for The Sporting News, still angry over the Dunlap signing and other suspected Watkins designs against the hometown Maroons. In a pair of December 1886 editorials, TSN blistered Windy Hawfulgall Watkins as a “peddler of franchises” and “an ill-mannered boor” intent upon undermining the good standing of the St. Louis club in NL councils.11 But while A.H. Spink and company were denouncing Watkins, the Maroons franchise was being targeted for acquisition by a different menace, a consortium of Indianapolis businessmen headed by department store magnate John T. Brush. Early in 1887, control of the NL St. Louis club was acquired by the Brush group and transferred to Indianapolis for the coming season.

The Wolverines got off quickly in 1887, winning 18 of their first 20 games and assuming the lead in NL standings. Notwithstanding that, there was dissention in the Detroit clubhouse, with the disciplinary measures of manager Watkins being a sore point. Particularly resented was Watkins’ tendency to fine lesser lights like catcher Fatty Briody and pitcher Stump Weidman for infractions that went unpunished when committed by team stars.12 He even got into arguments with opposition players. Near season end, it was reported that Indianapolis field captain Jack Glasscock had to be restrained by teammates from “wiping the thoroughfare” with Watkins.13

The 1887 season would prove the highlight of the Detroit Wolverines existence, and of Bill Watkins’ tenure as a major league executive. After a six-week spring training sojourn in Macon, Georgia,14 the Wolverines got off fast in the pennant chase and were never headed, the team dynamic improved by the voluntary withdrawal of the caustic-tongued Watkins from the Wolverines bench during games. But tensions remained between Watkins and his charges. But it mattered little in the end. With Sam Thompson (.372, with a NL-leading 166 RBIs) ably supported by Brouthers, Richardson, White, and Rowe, all of whom hit over .300, and a five-man pitching staff led by 29-game winner Getzien, the Wolverines captured the pennant with a handsome 79-45 (.637) log. Detroit then attained the title of baseball world champions, defeating the AA standard-bearing St. Louis Browns in a 15-game match, played to conclusion in ten different cities before ever-smaller galleries.15 But even a world championship title could not cure the financial ills of the Detroit franchise. With its population then under 150,000, Detroit proved unable to draw large crowds at home. NL owners, led by Eastern team magnates still smarting from Stearns’ absorption of the Buffalo franchise, then reneged on away-game gate receipt concessions accorded Detroit a year earlier. Unable to balance a payroll loaded with stars, the Wolverines slipped into red ink.

Nor was Bill Watkins a happy man. Club president Stearns’ failure to mention the Watkins name in a lengthy banquet tribute to the world champions had bruised the manager’s feelings.16 Then Watkins got into a nasty public dust-up with the revered Deacon White. The specifics of the dispute are murky but its nature can probably be inferred from the mea culpa that Detroit club directors extracted from Watkins: “Some of the statements made in the public press, alleged by [White] to have been made by me, I have never authorized. Other things I have said thoughtlessly, but with no malicious intent toward White. They were made on the spur of the moment and without consideration of their consequences or of the effects the remarks would have upon his feelings. … Realizing now that I have undoubtedly wounded his personal feeling by public expression, I now take occasion to repair the damage as far as possible.”17 This opaque non-apology did little to mollify White. Nor did it repair the strained relations that now existed between Watkins and his employers. With restive charges underperforming on the field and feeling besieged on all sides, Watkins resigned as Detroit manager in late August 1888, leaving the Wolverines (49-44, .527) in the middle of the NL pack. Replaced at the helm by club secretary Bob Leadley, Watkins had posted an excellent 249-161 (.607) log, with a recent world baseball championship to his credit, during his term as Wolverines overseer. The Detroit Wolverines would soon exit the scene, as well. His ambitions satisfied by the 1887 championship, the wealthy Stearns had thereafter relinquished control of the club to fellow directors. They, in turn, proved unable to bear the burden of financing a non-profitable major league baseball operation. Accordingly, those now in charge sold off the club’s star players and disbanded the Detroit franchise at the close of the 1888 season.

Following his departure from Detroit, Bill Watkins did not remain unemployed indefinitely. On September 7, 1888, he assumed the post of manager of the Kansas City Cowboys, the American Association cellar dwellers As in Detroit, manager Watkins’ duties were mainly in the front office, not on the bench. But lacking the fiscal resources once supplied by Stearns, Watkins was unable to turn club fortunes around. The following season, the Cowboys finished a non-competitive (55-82, .401) seventh place in AA standings and the franchise was dissolved shortly thereafter. Watkins began the ensuing season on the sidelines, but in late-June assumed command of the last-place and financially-troubled St. Paul Apostles of the Western Association.18 But the Apostles were a lost cause, with a playing roster so threadbare that Watkins even had to place himself occasionally in the lineup.19 At season end, (37-84, .308) St. Paul was securely ensconced in the circuit cellar, 43 games behind the pennant-winning Kansas City Blues.

Watkins returned to St. Paul in 1891, but with the club anchored in last place at 17-34, the franchise was shifted to Duluth, Minnesota, in early June. Two months later, the club disbanded. By then, Watkins had been supplanted as manager by Jay Anderson. Thereafter, Watkins spent at least part of the 1892 season as manager of the Rochester Flour Cities of the Eastern League. The following year, he resurfaced in the majors, becoming the latest in the parade of baseball men installed as manager of the once-proud St. Louis Browns by volatile owner Chris Von Der Ahe. Watkins, however, had no more success at the Browns helm than his most immediate predecessors and was dismissed after a tenth-place (57-75, .432) St. Louis finish in a National League now swollen to 12 teams.

In 1894, the Watkins odyssey continued as he became manager of the Sioux City Cornhuskers, an entry in the latest version of the Western League. With a lineup jammed with .300+ hitters and a pitching staff headed by 35-game winner Bert Cunningham, the (74-52, .587) Cornhuskers captured the WL pennant for manager Watkins. The following season, the Cornhuskers were removed to St. Paul by incoming club owner Charles Comiskey. But Watkins did not accompany the team. Rather, he signed on as manager of a Western League rival, the Indianapolis Hoosiers, a move that, in time, would place Watkins in the middle of a skirmish between the two executive giants of turn-of-the-century baseball: Ban Johnson and John T. Brush.

Originally a Cincinnati sportswriter, Johnson had assumed the presidency of the Western League upon its re-formation in October 1893. Able and energetic, Johnson soon transformed the new circuit into a premier minor league. Throughout its early existence, however, the Western League was nagged by the problem of competitive imbalance, a situation largely attributable to the maneuvers of Brush, the owner of the WL’s Indianapolis Hoosiers. By now, Brush was also president and majority owner of the National League Cincinnati Reds,20 whose roster Brush manipulated ruthlessly to Indianapolis advantage, fortifying the Hoosiers lineup for crucial games against WL rivals with Reds players, at times optioned to Indianapolis for no more than a weekend and then recalled to Cincinnati. With big league ringers at his disposal, Watkins managed Indianapolis to Western League pennants in 1895 and 1897, while his 1896 nine finished a solid second. By 1898, the complaints of fellow club owners had precipitated enactment of a prohibition against simultaneous ownership of a major and minor league baseball team, forcing Brush to relinquish (at least on paper) control of the Indianapolis club. By then, however, Bill Watkins had moved on, returning to the majors as pilot of the NL Pittsburgh Pirates.

In Pittsburgh, as elsewhere — with the notable exception of Detroit — Watkins was well liked, age and experience having greatly moderated his once-biting tongue, as reflected in the more frequent appearance of the semi-affectionate nickname Watty in newsprint.21 But sadly for Watkins, he got to Pittsburgh too soon, his installation as manager pre-dating the arrival of Honus Wagner, Tommy Leach, Deacon Phillippe, Sam Leever, and the other Pirate stalwarts who would shortly make Pittsburgh the class of the National League. Saddled with mediocrities, Watkins guided the Pirates to an eighth place (72-76) finish in 1898. The following season, the Pirates started 7-15, and Watkins resigned. Although his baseball career would continue for another two decades, Bill Watkins’ days as a major league manager were now over. In five different locales, Indianapolis (1884: 4-18); Detroit (1885-1888: 249-161); Kansas City (1888-1889: 63-99); St. Louis (1893: 57-75), and Pittsburgh (1898-1899: 79-91), Watkins-led clubs had posted a 452-444 (.504) regular season log, while taking 10 of the 15 post-season games that gave Detroit the 1887 world championship.

In 1900, Watkins returned to Indianapolis where he resumed command of the Hoosiers, now a member of the American League, the new moniker bestowed on the Western League by Ban Johnson in anticipation of declaring his circuit a major league in 1901. A prudent conservator of his own resources, Watkins now had the financial wherewithal to assume majority ownership of the Indianapolis club as well.22 That season, owner-manager Watkins led the Hoosiers to a third place (71-64, .526) finish in the AL of 1900. In the ensuing off-season, Watkins became embroiled in a new and far more momentous clash between Ban Johnson and John T. Brush — the battle over the establishment of a new major league in baseball.

Johnson had made no secret of his ambitions for the American League, and NL magnates had played right into his hands. Following the 1899 season, the senior circuit had contracted from 12 clubs to eight, freeing up major league-quality venues like Washington, Baltimore, and Cleveland for settlement by the American. At the conclusion of the following year, Johnson moved right in, jettisoning Indianapolis (as well as Buffalo, Kansas City, and Minneapolis) from his circuit in the process. Meanwhile, NL club owners, preoccupied with squabbling among themselves, were slow to respond. Belatedly in January 1901, NL leaders, led by Brush and encouraged editorially by Sporting Life founder Francis C. Richter, engineered the revival of the old American Association, now defunct for a decade. To be stocked with surplus NL players, AA franchises would be established in Chicago, Philadelphia, Boston, Baltimore, Washington, Milwaukee, and Detroit, while incorporating the Indianapolis team just abandoned by Johnson’s circuit.

In short order, Indianapolis owner/president/manager William H. Watkins emerged as AA spokesman and interim chairman/league president. “The AA is not a dream,” proclaimed Watkins. “It is an absolute fact. We have the cities and we have the financial backing of reputable and responsible businessmen in every one of them.”23 Despite cheerful weekly progress reports published by Sporting Life, the new AA never got off the drawing board, quickly undermined by NL owners like John I. Rogers of Philadelphia and Boston’s Arthur Soden who wanted neither an American League nor an American Association rival in his city. With Brush and Watkins the target of most public finger-pointing, the AA revival was stillborn, its passing noted sadly by Richter in mid-March.24

These developments left Bill Watkins the owner of a professional baseball team with no league to play in. Scrambling, Watkins secured a berth for Indianapolis in the Western Association, a second-tier minor league. The caliber of WA play proved unacceptable to Indianapolis fans, only 400 of whom would attend a typical Hoosiers game. In mid-July, Watkins sold the club to new owners who removed the franchise to obscure Matthews, Indiana, to complete the season. But a brighter baseball future for Watkins and Indianapolis was on the horizon. In November 1901, an Indianapolis club newly assembled by Watkins joined one-time major league cities like Louisville, Milwaukee, Kansas City, Columbus, and Toledo, plus St. Paul and Minneapolis, to form the independent minor league American Association, destined to become one of baseball’s most stable professional circuits.25

Laced with major league-quality material like outfielder George Hogreiver (a league-leading 124 runs scored) and pitchers Win Kellum (25-10), Jack Sutthoff (24-13), and Frank Killen (16-6), Watkins, fully exercising the duties now commonly associated with being a baseball team manager (in addition to being club owner and president), guided the Indianapolis Indians to the maiden AA pennant, its 96-45 (.681) final season mark good for a two-game margin over Louisville.26 The following season, however, Indianapolis dropped to fourth place (78-61, .561) and placed dead last in home attendance (88,000) among AA clubs. In early 1905, Watkins resigned as Indianapolis club president/manager to take over the reins of AA rival Minneapolis. But after a disappointing campaign leading the Millers, Watkins sold the Minneapolis franchise to former St. Paul manager Mike Kelley for a reported $25,000 in December.

But Bill Watkins was far from through with baseball. In 1906, he reacquired the Indianapolis franchise, reinstalling himself as the Indians president/manager. This time, however, on-field success eluded him as a field skipper. With Indianapolis headed for last place, Watkins resigned as manager, tapping first baseman Charlie Carr to preside over the club’s 53-96 (.356) finish. For the next five years, Watkins confined himself to front office duties for the Indians, reveling in the 1908 pennant brought in by manager Carr behind the exploits of future major league standouts Rube Marquard and Donie Bush. Thereafter, disputes with front office subordinates gradually soured Watkins on Indians baseball. On May 23, 1912, Watkins, now approaching his 54th birthday, resigned as Indianapolis club president and sold the team, returning home to Port Huron to tend to his farm and business interests.27 But not for long.

But Bill Watkins was far from through with baseball. In 1906, he reacquired the Indianapolis franchise, reinstalling himself as the Indians president/manager. This time, however, on-field success eluded him as a field skipper. With Indianapolis headed for last place, Watkins resigned as manager, tapping first baseman Charlie Carr to preside over the club’s 53-96 (.356) finish. For the next five years, Watkins confined himself to front office duties for the Indians, reveling in the 1908 pennant brought in by manager Carr behind the exploits of future major league standouts Rube Marquard and Donie Bush. Thereafter, disputes with front office subordinates gradually soured Watkins on Indians baseball. On May 23, 1912, Watkins, now approaching his 54th birthday, resigned as Indianapolis club president and sold the team, returning home to Port Huron to tend to his farm and business interests.27 But not for long.

In February 1914, Watkins returned to Indianapolis to assume the post of business manager for the renegade Federal League Hoosiers, the eighth and final time that Watkins would serve a professional baseball organization seated in the Indiana capital. “I am glad to get back into harness and particularly glad to return to Indianapolis,” Bill declared upon signing on.28 The Federal League crown captured by the 1914 Indianapolis club was the sixth pennant winner that Bill Watkins would be associated with. It was also his last. Watkins resigned his position with the organization when the Indianapolis franchise was acquired by oil tycoon Harry Sinclair and transferred to Newark for the 1915 season. Once again, Watkins returned to Port Huron to attend to his interests there, his thirty-year involvement in professional baseball seemingly at its end.

Back home, Watkins immersed himself in local business affairs, serving in executive positions at various Port Huron banks, land development companies, and manufacturing concerns, and as president of the Port Huron Chamber of Commerce. A naturalized American citizen since 1897, Watkins was also active in civic matters, particularly after taking up residence in Marysville, a fledgling nearby community that he helped to establish.29 In 1919, Watkins served as the first president of the village of Marysville, and thereafter chaired the committee that upgraded Maryville’s municipal status to that of a city. Simultaneously, Watkins maintained his interest in baseball. He declined an offer to return as Indianapolis Indians manager in 1918,30 but took keen interest in the local game. He was a financial backer of the Port Huron Saints of the Class B Michigan-Ontario League, and served as club president in 1921-1922. In appreciation for his support, Saints home games and those of the local high school were played at a downtown Port Huron field named in Watkins’ honor.

Watkins remained a leading citizen of his new home town, even at an advancing age. He served on the Marysville Board of Education for ten years and was elected Justice of the Peace in November 1933. In early 1937, Watkins’ health began to fail. Hospitalized for a month in Port Huron, he died there of diabetes complications on June 9, 1937, age 79. Following services at Grace Episcopal Church, Watkins was interred at Lakeside Cemetery in Port Huron. Without children, he was survived by wife Edna and sisters Lily Shilton and Ella Crisp.

In the ensuing years, Bill Watkins slowly faded from collective consciousness. Watkins Field was razed in the early 1940s and area residents who knew him personally steadily passed away. Decades later, however, the research of baseball historian Marc Okkonen brought the Watkins legacy back to local attention. And in October 2008, long deceased William H. Watkins was inducted into the Port Huron Sports Hall of Fame,31 a modest but apt testimonial to a bygone but well-spent life.

Sources

The biographical details provided above are drawn primarily from material furnished the writer by Reference Librarian Barbara Kirk of the St. Clair (Michigan) County Library system and Local History Librarian Denise Kirk of the Brantford (Ontario) Public Library. Other sources included the Bill Watkins file at the Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York: US Census data and other Watkins family info accessed via Ancestry.com; and certain of the newspaper articles cited in the endnotes. Stats have been taken from Baseball-Reference.

This biography was updated and revised in January 2021.

Notes

1 Beginning with the 1951 first edition of the baseball encyclopedia of Turkin & Thompson to presently, modern reference works have erroneously listed our subject’s birth name as William Henry Watkins. Efforts to correct Bill Watkins’ biographical data were ongoing at the time this bio was revised. William Harton Thomas Watkins took his middle name from his grandmother Barbara Mary Jane Harton Watkins (1774-1847), an immigrant to Canada and the daughter of Anglo-Irishman Daniel Harton of County Offaly.

2 Bill’s siblings were sisters Lily (Sarah Barbara Eliza, born 1855), Ella (Mary Ellen Louise, 1860), and Anne (1862). Youngest sister Lizzie (1865) did not survive infancy.

3 John L.H. Watkins promptly remarried, taking Ann Hoyle as his second wife in 1869. Why son Bill remained thereafter in the care of his grandparents is unknown.

4 Per the Watkins obituary published in the (Port Huron, Michigan) Times Herald, June 10, 1937: 1.

5 Port Huron and nearby Michigan communities are separated from Ontario, Canada, by the St. Clair River.

6 Per “Death Strikes Out Veteran of Baseball,” Times Herald, June 10, 1937: 1-2.

7 Current authority such as Baseball-Reference and Retrosheet designate Watkins a righty batter, with his throwing arm listed as unknown. By the mid-1880s, however, left-handed second basemen had become a rarity.

8 The appraisal offered in Sporting Life, August 20, 1884: 4.

9 In obituaries and post-mortem remembrance it was claimed that the Shallix beaning caused Watkins’ hair to turn white virtually overnight. See e.g., “Necrology,” The Sporting News, June 17, 1937: 2; Edgar G. Brands, “Beanball Turned Watkins’ Hair White,” The Sporting News, July 8, 1937: 4. This piece of Watkins folklore, however, is belied by post-beaning photographs, all of which show the auburn-headed Watkins with darkish hair and mustache until he was well into middle age.

10 Sporting News founder Al Spink was convinced that Watkins had tried to break up the hometown Maroons, an offense that Watkins later compounded via an unintentional snub of Spink at a meeting of St. Louis club supporters. Spink retaliated with an uncomplimentary editorial. See The Sporting News, December 18, 1886: 2.

11 See TSN editorial blasts published December 11 and 18, 1886.

12 In reaction to the Briody and Weidman sanctions it was reported that “dissention is rife throughout the [Detroit] club, but Watkins does not have the guts to fine the more prominent malcontents,” as per an unidentified July 21, 1887 news item contained in the Bill Watkins file at the Giamatti Research Center.

13 See “Glasscock and Watkins,” The Sporting News, September 3, 1887: 1.

14 The Macon trip admits Watkins into that legion of claimants upon the title of initiator of baseball spring training in the South.

15 Game 14 in Chicago drew only 378 paying spectators.

16 As subsequently revealed in “The Detroit Row,” Chicago Tribune, March 19, 1888: 3.

17 “Manager Watkins Amende Honorable,” Washington Post, March 19, 1888: 1.

18 As revealed in “Now in New Hands,” St. Paul Globe, June 28, 1890: 5.

19 On August 12, 1890, Watkins played an errorless right field but went 0-for-3 at the plate in an 8-1 loss to Lincoln. It was the first regular season game played by the now 32-year-old since the 1884 season.

20 Over Brush’s vigorous objection, the National League had liquidated this weak Indianapolis franchise in early 1890 as a preemptive measure in the coming battle with the newly-arrived Players League. Brush, however, retained his seat on the NL owners’ council and was promised the next available franchise which, in 1891, turned out to be Cincinnati.

21 See e.g., “Watkins Goes to Pittsburg,” Indianapolis Journal, November 14, 1897: 9; “Sporting Gossip,” Sioux City (Iowa) Journal, November 27, 1898: 2: “‘Watty” Don’t Buy,” Duluth (Minnesota) News-Tribune, October 27, 1899: 2.

22 Watkins’ minority partner in Indianapolis club ownership was local businessman Charles F. Ruschaupt, although sentiment lingered that the two men were no more than a front for the club’s true owner, their friend John T. Brush. In time, however, the bona fides of the Watkins-Ruschaupt partnership became evident.

23 “New Baseball Factor,” Washington Post, January 15, 1901: 8.

24 See Sporting Life, March 9 and 16, 1901. For more detail on Watkins’ role in the aborted attempt to revive the American Association, see Bill Lamb, “Thrice Stillborn: Turn-of-the-Century Attempts to Revive the Once-Major League American Association,” Base Ball 11: New Research on the Early Game (McFarland, 2019), 156-161.

25 The American Association played the 1902 season as an independent organization outside the provisions of the National Agreement. The AA was admitted to Organized Baseball the following year, and remained in continuous operation as a top-echelon minor league through the 1962 season. Watkins’ partner in the new Indianapolis venture was again Charles F. Ruschaupt, the firm of Watkins & Ruschaupt being listed as “proprietors of the Indianapolis Base Ball Club” in Indianapolis city directories, 1901-1905.

26 More than a century later, baseball historians Bill Weiss and Marshall Wright rated the 1902 Indianapolis Indians 27th in their ranking of the top 100 teams in minor league baseball history, at http://www.mib.com/history/top100.jsp?idx=27.

27 Baseball-Reference’s inclusion of our Bill Watkins among the five managers of the 1911 Huntsville (Alabama) Westerns of the Class D Southeastern League is erroneous. Among other places, Watkins’ retention of his post in Indianapolis during the 1911 season is attested by correspondence contained in the Garry Herrmann file at the Giamatti Research Center. Various 1911 letters to Herrmann bear the Watkins signature on stationary with the letterhead: “W.H. Watkins, President, Indianapolis Athletic Association,” the corporate name of the Indianapolis Indians franchise.

28 Per “‘Watty’ Comes to Terms,” Indianapolis Star, February 1914: 1.

29 According to the Watkins obituary in the Times Herald, June 10, 1937: 1-2.

30 See “Refuses to Come Back,” Washington Post, February 21, 1918: 8.

31 Per “Former Area Resident ‘Very Worthy of Honor,’” Times Herald, October 24, 2008: 11.

Full Name

William Harton Thomas Watkins

Born

May 5, 1858 at Brantford, ON (CAN)

Died

June 9, 1937 at Port Huron, MI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.