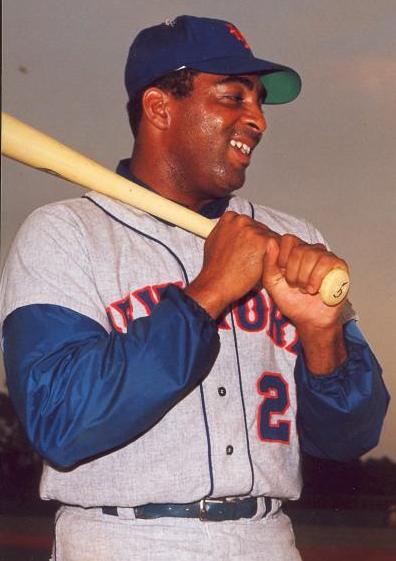

Tommie Agee

Tommie Agee was one of the key components to the 1969 Miracle Mets, solidifying the defense and serving as the club’s chief power source, albeit from the leadoff spot. His on-field heroics during the ’69 season—including socking the only home run to ever reach Shea Stadium’s upper deck—helped propel the Mets to their first postseason berth and an unlikely journey to the World Series. Once there, Agee’s heroics turned to legend. In Game Three of the Fall Classic he hit a leadoff home run and made two Amazin’ catches to ensure a New York victory. He signed a large bonus with Cleveland, was a Rookie of the Year with the White Sox, and spent his last season in Houston and St. Louis, but he will always be remembered as a Met patrolling center field next to his childhood buddy.

Tommie Agee was one of the key components to the 1969 Miracle Mets, solidifying the defense and serving as the club’s chief power source, albeit from the leadoff spot. His on-field heroics during the ’69 season—including socking the only home run to ever reach Shea Stadium’s upper deck—helped propel the Mets to their first postseason berth and an unlikely journey to the World Series. Once there, Agee’s heroics turned to legend. In Game Three of the Fall Classic he hit a leadoff home run and made two Amazin’ catches to ensure a New York victory. He signed a large bonus with Cleveland, was a Rookie of the Year with the White Sox, and spent his last season in Houston and St. Louis, but he will always be remembered as a Met patrolling center field next to his childhood buddy.

Tommie Lee Agee was born August 9, 1942, at Magnolia, Alabama to Carrie and Joseph Agee. He had 10 siblings, nine of them girls. A year after Tommie’s birth, the Agees moved to Mobile, Alabama. His father worked for the Aluminum Company of America and Agee grew up in a low-income area that had segregated schools and parks. Being on the Gulf of Mexico, Mobile’s climate lent itself to year-round outdoor sporting activities. The locality also had a rich lode for baseball talent, Hank Aaron and Willie McCovey hail from the area as did legendary Satchel Paige and Agee’s Mets teammate Amos Otis. But it was another future teammate in New York that Agee would form a bond with in Mobile.

In junior high, Agee met another youngster, Cleon Jones, who became an immediate school yard teammate and close friend. They were born just five days apart (Cleon was older). Although Carrie Agee wanted her son to become a minister, early on Tommie demonstrated gifted athletic abilities and a desire that placed him on course for a sports career.

Though not yet five years old when Jackie Robinson brought an end to the infamous gentlemen’s agreement and opened up major league rosters to men of color, Agee still recalled the excitement it generated. “They had one television set in our part of town and everybody gathered around it one day when Jackie Robinson was playing a game. ..I knew then that I could be a ballplayer.”1

Agee attended the local high school, Mobile County Training School. Started in 1880, the facility was the oldest training school in Alabama and for many years was comprised of grades seven through 12. It was reorganized to a middle school in 1970. Agee was a four-sport star at Mobile County, playing football, basketball, and baseball as well as running track. During summer break the teenager played sandlot baseball. In fact, he once shagged flies for another Mobile resident, future Hall of Famer Billy Williams.

“There were quite a few playing fields around,” said Agee’s high school coach, Curtis J. Horton. “The boys had areas in which they could develop.. ..Fields didn’t have to be perfect and smooth. Baseball was played in just about every neighborhood, on every block. If the kids didn’t have regulation bats and balls, they played stickball with rubber balls and broomsticks.”2

On the high school diamond, Tommie batted .390 and also pitched. The team recorded only one loss. Unfortunately, Alabama did not have a state baseball championship while Agee was at Mobile County Training School.

On the gridiron, Agee was an end and his friend Cleon Jones, a halfback. MCTS football had a stellar record—only one loss during Tommie’s three years with the squad. He would remember fondly, “We had a play that we called number forty-eight, and it was a halfback option play. The quarterback would hand off to Cleon and he had an option of running or passing to me. During the 1960 season, we made five touchdowns on that play alone.”3

Agee went on to Grambling State University on a baseball scholarship, a school better known for other sports: NBA star Willis Reed and NFL cornerback Willie Brown, both of whom eventually reached the Hall of Fame in their sports as professionals, attended Grambling the same time as Agee. Dr. Ralph Waldo Emerson Jones who coached the Louisiana school’s baseball team remembered Tommie’s first game. “We worked on cutting down his swing. You know how it is, all these boys think about is home runs… .Well, the first time up, he hits a home run over the left-field fence. The next time he hits one over the center-field fence. The third time he hits one over the right-field fence. Then he hits so far into center that he gets an inside-the-park home run.”4

Early scouting reports claimed he “lacked coordination” as well as poor fundamentals. In fact, Coach Jones initially placed him at first base. The coach moved him to the middle infield and even had him pitch before finally slotting Agee as an outfielder. Hitting was not an obstacle. During his single season at Grambling, Agee batted .533, then the highest average in the Southwestern Athletic Conference’s history.

After that colossal college season seemingly every pro birddog scout flocked to Agee’s home in Mobile. Similarly impressed was his pal Cleon Jones, who took to respectfully referring to Agee as “Number One.”5

Agee inked a contract with the Cleveland Indians with a $65,000 bonus in 1961. He spent parts of two season in Iowa, first at Class-D Dubuque, where he hit .261 with 15 home runs in 64 games, and then at Class-B Burlington, batting .258 with 25 steals in 500 at-bats. He moved up to Class-AAA Jacksonville for two games before being called up to Cleveland. His major league debut occurred in road grays, September 14, 1962 before 25,372 at Metropolitan Stadium. In the top of the ninth, the 5-foot-11, 195-pound Agee flew out against Minnesota southpaw Dick Stigman in an 11-1 Minnesota rout. Agee batted .214 during that initial cup of coffee in 1962. He bounced back and forth from the farm to the parent club through the 1964 season. His cumulative batting average for Cleveland was just .170 with one home run in 53 at-bats.

On January 20, 1965, the 23-year-old Agee was involved in a three-team swap. Pitcher Tommy John, catcher John Romano, and Agee were sent to the Chicago White Sox; the Kansas City Athletics sent Rocky Colavito to Cleveland; Chicago sent Jim Landis and Mike Hershberger to Kansas City; and Chicago sent Cam Carreon to Cleveland. At a later date Chicago sent Fred Talbot to Kansas City. The White Sox wound up the winners in the complicated transaction, though Agee did not pay immediate dividends.

Agee spent almost all of 1965 at Class-AAA Indianapolis, batting .226 with 15 steals. He hit even worse in brief duty with the Pale Hose, batting a paltry .158. Agee finally got his chance in 1966.

Agee was tabbed as Chicago’s starting center fielder on Opening Day and launched a two-run home run in the seventh inning to tie the game. The White Sox went on to win in 14 innings and Agee, who began the season in the seventh spot in the order, quickly moved up in the lineup—first to leadoff, then moving to the two-hole, before settling into the third spot in the order. He wound up the season batting cleanup.

Agee batted .273 with 22 home runs, 88 RBIs, and scored 98 runs while playing in 160 games. After attempting just one steal in his past trials in the majors, Agee stole 44 bases for the White Sox (he was caught 18 times). He was named the American League Rookie of the Year and finished eighth in the MVP voting to Triple Crown winner Frank Robinson in Baltimore. Agee earned a Gold Glove and was named to the All-Star team.

Agee was an All-Star again in 1967, but he suffered through a sophomore jinx in the latter stages of the season. He managed through the first half with a split of .247/.317/.401—not bad numbers for that pitching-dominated era on a team where no regular wound up hitting higher than .250—but Agee slumped to .218/.282/.329 in the second half. And while he thrived against lefties, batting .306 and putting together an .844 OPS, he made management wonder if he might be a platoon player by hitting just .199 against righties, though he hit 10 of his 14 home runs against them. His slumping was certainly noticeable as the Chisox battled until the final week for the pennant with Boston, Detroit, and Minnesota; the club with scarlet socks nabbed the AL flag on the final day.

Also noticing the outfielder was opposing manager Gil Hodges of the Washington Senators. When the New York Mets traded for Hodges after the season, one of the new manager’s first requests was to try to pry Agee from the White Sox. On December 15, 1967, the Mets acquired Agee along with infielder Al Weis. The Mets gave up their best hitter, Tommy Davis, and Jack Fisher, the only Met besides rookie Tom Seaver to make more than 30 starts in 1967. (The Mets also sent Billy Wynne and Buddy Booker to the White Sox in the deal.)

Hodges penciled in Agee as his center fielder, a position where many had tried and failed for the sad-sack Mets to that point. Longtime Mets beat reporter Maury Allen wrote, “Hodges had always liked Agee as a ballplayer and thought sure that he could be the kind of exciting leader the Mets needed on the field.”6 The deal also reunited Agee with long-time friend and Mets left fielder Cleon Jones.

The ’68 Grapefruit League opener was a bleak foreshadowing for Agee’s first year as a Met. He was beaned by St. Louis Cardinals ace Bob Gibson on the first pitch of spring training and wound up hospitalized. Agee began the regular season batting third with a 5-for-16 start, good for a .313 average and five runs scored. In the fifth game, however, he endured an 0-for-10 nightmare in a 24-inning loss at the Astrodome, embarking on a 0-for-34 slump that tied Don Zimmer’s club record set in 1962. After going hitless for two weeks and seeing his average drop to .102, he finally grounded a single off Philadelphia’s Larry Jackson. He did not have his first home run or RBI until May 10. Agee ended the year with a .217 batting average and a mere five home runs and 17 RBIs in 391 at-bats. He walked just 15 times—his lowest total over a full season—while fanning 100 times for the third straight year.

Oddsmakers and baseball pundits tagged the 1969 Mets as a 100-1 longshot to win the Fall Classic. Why? Since their inception the hapless club never finished higher than ninth place. The smart money knew only a miracle could turn them around and that wasn’t going to happen. Or was it?

Agee, fittingly, was the first Mets batter of 1969. Primed for redemption and rewarding his manager’s faith by installing him in the leadoff spot, he knocked in New York’s first runs of the season with a three-run double in the second inning on Opening Day. Two days later, on April 10, the 26-year-old launched two home runs. His first of the day was a legendary homer in the second inning that landed in Shea’s left-field upper deck.

“That one today would have gone over the third fence and hit the bus in the parking lot if it hadn’t hit the seats,” marveled Ron Swoboda.7

After that blast plus another off Expos left-hander Larry Jaster, Agee said the chance Hodges gave him to go deep meant as much to him as the jaw-dropping distance. “Not many managers,” he said, “would have had enough faith to go with me after the year I had [in 1968].”8

Agee was the first—and last—to ever land a ball in the ratified air of fair territory in left or right field at Shea Stadium. The approximate spot was later memorialized by painting a large circle where he hit his home run with his name, number, and date. Years later, it was estimated at 480 feet.

But long balls were a generally rare event with the Mets. A pitching-first club without a lot of hitting, the 1969 Mets won by scoring just enough runs to win. They went a remarkable 41-23 in one-run games in 1969, often relying on their “lunch pail” everyday center fielder to inspire teammates. “I think it was just a matter of [Agee’s] getting adjusted, knowing the pitchers better and regaining his confidence,” Hodges said. “Tommie can make a ballclub go with running and power.”9

Agee led the 1969 Mets in games (149), at-bats (565), runs (97), and, surprisingly for a leadoff man, he led the club in both home runs (26) and RBIs (76). Though he had a superb season with his glove in center field, Cincinnati Reds right fielder Pete Rose wound up claiming a Gold Glove along with automatics Roberto Clemente and Curt Flood. Rose finished fourth in the MVP voting to Willie McCovey; Agee was sixth.

Agee’s offense garnered plenty of notice. Allen, who covered the club for the New York Post that summer, referred to 1969 as “the Mets Age of Agee,”10 bumping the Age of Aquarius from Broadway’s production of Hair to second billing.

Indeed, the Cubs must have been perusing the Big Apple tabloids. The first pitch of the September 8 showdown by Cub Bill Hands knocked down Agee. To veteran observers, it had all the earmarks of a “stick it in his ear” order from Cub skipper Leo Durocher.11 After that game, which New York won with Agee sliding past catcher Randy Hundley in a memorably close call, the outfielder commented, “I don’t mind being knocked down. If you’re hitting they’re going to knock you down. The only thing I don’t like is if we don’t retaliate.” Jerry Koosman took care of that end and the Mets—with a visit from a black cat—took care of the Cubs the next night and took over first place the night after that.

The Mets mowed down the opposition, finishing with a 100-62 record. The Amazin’s topped the second place Cubs by eight games and captured the first National League East title in history. The inaugural Championship Series saw New York square off against the West’s Atlanta Braves. Agee, who played every day despite Hodges’s multiple platoon system, batted leadoff in all three games. After becoming the first Mets to ever appear in a postseason game and going hitless in the series opening win, Agee homered in each of the next two games and knocked in four for a .357 average as the Mets swept.

Agee was the first Met to step to the plate in a World Series game and—as he’d done in the NLCS opener—he grounded out. Orioles outfielder Don Buford—a former teammate of Agee’s in Chicago—belted a leadoff home run against Tom Seaver as Baltimore took the first game, 4-1. The Mets held on for a 2-1 win the next day to even the Series.

Agee took over Game Three and the Mets shifted into another gear. Sports Illustrated labeled Agee’s October 14 performance, “The most spectacular World Series game that any center fielder has ever enjoyed.”12 Agee led off the first World Series game played at Shea with a home run against Orioles ace and future Cooperstown entrant Jim Palmer. Agee had been 0 for 8 in the two games in Maryland.

New York was up 3-0 in the fourth inning, but the Orioles threatened with runners on first and third and two outs. Baltimore catcher Elrod Hendricks hit a Gary Gentry pitch to left-center. It looked like a double or even a triple for the Baltimore backstop. As Agee sprinted toward left field, Cleon Jones knew his old friend would make the play. “Lots of room, lots of room!” Jones shouted, to make sure Agee knew the fence wouldn’t get in his way.13 Agee reached out and grabbed the ball backhanded as he came to a halt before slamming into the 396-foot sign—with plenty of white showing as the ball lodged in the glove’s stretched webbing.

Baltimore loaded the bases in the seventh with two outs. Orioles center fielder Paul Blair represented the tying run as Nolan Ryan came in to replace Gentry. Blair slammed a drive to deep right-center field as Agee again sped in pursuit. At the warning track he dove for the ball as if he were an Olympic swimmer. The ball landed in his glove as he sprawled prone to the ground. Agee later said the catch off Blair, as difficult as it looked, was easier than the one he made off Hendricks because the Blair catch was “on my glove side.”14

The 56,335 at Shea gave him a standing ovation when he led off in the bottom of the frame. Agee also received what may have been the ultimate compliment from the wags in the press box who winkingly told one another between catches, “Let’s see him do it again.”15 Little did they know they would.

Agee’s catches, especially his robbery of Blair, were immediately considered within the regal realm of other key Series plays: great grabs like Al Gionfriddo off Joe DiMaggio (1947), Willie Mays off Vic Wertz (1954), or Sandy Amoros off Yogi Berra (1955). After the contest, Agee was particularly satisfied that his all-around performance would make headlines back home in Mobile. “Oh, people hear about us,” he said. “They get clippings from out of town.”16

Agee’s leadoff homer accounted for one run and the catches saved at least five runs in the 5-0 win that put the Mets ahead of the overwhelming favorite Orioles in the World Series. Agee had just two more hits in the Series and finished with a .167 average in the five-game victory, but he was still as much a hero as anyone on a team suddenly overflowing with supermen.

Following the World Series, Agee along with a few other Mets appeared in a Las Vegas revue, singing “The Impossible Dream” among other standards. Back in Mobile, Agee and Jones were honored with a parade. Though Agee would later admit disappointment that as a pair of African-American big-leaguers he and Jones weren’t previously the object of much official municipal affection in their Deep South hometown, on the day of the celebration, he happily told the estimated crowd of more than 5,000, “There’s no place like home.”17

The Sporting News named Agee NL Comeback Player of the Year. He continued to be the club’s leadoff hitter and starting center fielder for three more seasons. He won his overdue second Gold Glove in 1970 and surpassed his ’69 season in several categories. He batted a career-high .286 and had his lone career 30-double season. That year also saw him set team records with 636 at-bats, (broken by Felix Millan in 1973 with 638), 31 stolen bases (topped by Lenny Randle in 1977 with 33), 107 runs (surpassed by one by Darryl Strawberry in 1987), and 298 total bases (erased by Strawberry in ’87 with 310). Agee had both a 20-game and a 19-game hitting streak in ’70 while his 24 home runs made him the first Met in history to twice lead the club in that category or reach 20 homers in more than one year.

The 1971 and 1972 seasons saw Agee hampered by knee problems. Before the 1972 season, Hodges died suddenly, and Yogi Berra was named manager. More change was in store on May 11 when the Mets acquired the greatest center fielder to ever come from Alabama: Willie Mays. Agee still got the majority of starts in center field over the 41-year-old Mays, but he no longer played every day as he had under Hodges. His average stood at .281 the day Mays had his first at-bat as a Met and Agee finished the year at just .227, his lowest average since his first year at Shea.

On November 27, 1972, the Mets dealt Agee to the Houston Astros for outfielder Rich Chiles and right-hander Buddy Harris. Agee appeared in 83 games for Houston and batted .235 with eight home runs. The Astros sent him to the St. Louis Cardinals on August 18, 1973, receiving outfielder Dave Campbell and cash. His last game was September 30, 1973 at Busch Stadium, where he pinch-hit for pitcher Diego Segui in the fifth inning against the Philadelphia Phillies. Agee grounded out to short.

Agee had planned to continue playing and the Los Angeles Dodgers fully expected him to as well. On December 5, 1973, the Cards traded him to Los Angeles for Pete Richert, but the Dodgers released Agee near the end of spring training on March 26, 1974. Agee ended his career, at age 31, with a .255 batting average with 130 home runs, 433 RBIs, and 167 stolen bases. He finished one hit shy of 1,000 for his career.

In retirement, Agee was very active in youth programs in the New York area. He owned a bar near Shea Stadium called The Outfielder’s Lounge. He later went into the business sector and was affiliated with Stewart Title Insurance Company. On January 22, 2001, upon leaving a midtown Manhattan office building, Agee was stricken with a fatal heart attack. He was 58 years old. Agee was survived by his wife Maxine and daughter Janelle.

Mets team chairman Nelson Doubleday called Agee “one of the all-time great Mets.” On Opening Day 2001 the Mets wore a patch honoring Agee and Brian Cole, a prospect killed in an auto accident shortly before the opener. Agee was inducted into the Mets Hall of Fame in 2002, the last Met so honored at Shea Stadium. Members of his family were invited to take part in the final day at Shea in 2008.

After Agee’s death, Cleon Jones still marveled at how his old friend made playing center field at Shea Stadium look easy, despite its poor visibility and swirling winds. “I hated it; every guy before me hated it,” recalled Jones, who was the club’s center fielder the two years prior to Agee’s arrival in New York. “But Tommie never complained. I watched Willie Mays, Curt Flood, Vada Pinson—a lot of guys came into this Shea Stadium outfield. Nobody played it better than Tommie Agee.”18

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Special thanks to Mets fan Greg Prince, who researched and provided all the endnotes for this biography.

SOURCES

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted 108mag.typepad.com, Baseball Digest, guardonline.com, salisburypost.com, the 2008 Mets Media Guide, and two articles in particular.

Rubin, Adam, “Shea Stadium’s Been Raining Long Balls for Years,” http://www.nydailynews.com/sports/baseball/mets/2008/09/06/2008-09-06_sh…

Spector, Jesse, “Tommie Agee’s Upper-Decker Remains Singular Shea Swat” http://www.nydailynews.com/sports/baseball/mets/2008/09/20/2008-09-20_tommie_agees_upperdecker_remains_singula.html#ixzzOEZQaM9Hs&A

NOTES

1. A.S. “Doc” Young, The Mets From Mobile: Cleon Jones and Tommie Agee (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1970), 24.

2. Young, 20.

3. Young, 22.

4. Young, 26.

5. George Vecsey, Joy in Mudville: Being a Complete Account of the Unparalleled History of the New York Mets from Their Most Perturbed Beginnings to Their Amazing Rise to Glory and Renown (New York: The McCall Publishing Company, 1970), 161.

6. Maury Allen, The Incredible Mets (New York: Paperback Library, 1969), 83-84.

7. Larry Fox, “Agee Reborn,” New York Daily News, April 11, 1968.

8. Fox, “Agee Reborn.”

9. Young, 60-61.

10. Allen, 125.

11. Vecsey, 209.

12. William Leggett, “Never Pumpkins Again,” Sports Illustrated, October 27, 1969.

13. Wayne Coffey, They Said It Couldn’t Be Done: The ’69 Mets, New York City, and the Most Astounding Season in Baseball History (New York: Crown Archetype), 183.

14. Young, 107.

15. Phil Pepe, “Agee Whiz! Mets Go 1 Up in Series,” New York Daily News, October 15, 1969.

16. Vecsey, 240.

17. Young, 134.

18. Bryan Hoch, “Agee Earns Rightful Sport in Mets Hall,” The Wave (Rockaway, New York), August 17, 2002.

Full Name

Tommie Lee Agee

Born

August 9, 1942 at Magnolia, AL (USA)

Died

January 22, 2001 at New York, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.