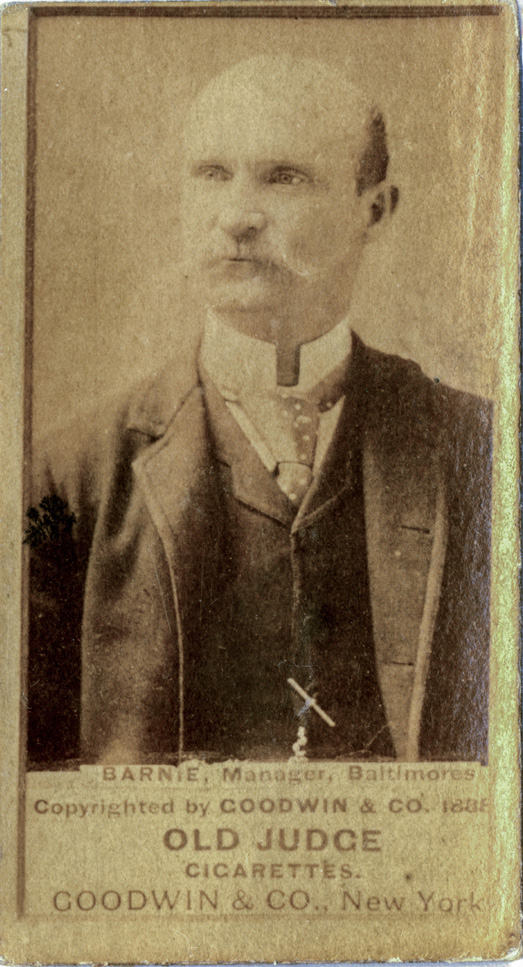

Billy Barnie

Billy Barnie touched all aspects of baseball before his untimely death in 1900 at age 49. This includes player trades, player contracts, home and away uniforms, three strikes and out, modern schedule making, five-pointed home plates, all-star teams, coaching boxes, overhand pitching, ballpark construction, championship rings, and daily game promotion. Barnie held every conceivable baseball position, settling on “manager” during a time when the front office had not yet evolved. He had a role in the creation of the Brooklyn Dodgers, Philadelphia Phillies, Baltimore Orioles, and Washington Senators franchises, and Barnie is the reason the Pittsburgh Pirates are called the Pirates. He also helped develop NL franchises in Louisville and Buffalo, as well as strong International Association franchises in Albany and Columbus in the late 1870s. Upon his death the newspapers called him “the best known baseball man outside of Nick Young.”1

Billy Barnie touched all aspects of baseball before his untimely death in 1900 at age 49. This includes player trades, player contracts, home and away uniforms, three strikes and out, modern schedule making, five-pointed home plates, all-star teams, coaching boxes, overhand pitching, ballpark construction, championship rings, and daily game promotion. Barnie held every conceivable baseball position, settling on “manager” during a time when the front office had not yet evolved. He had a role in the creation of the Brooklyn Dodgers, Philadelphia Phillies, Baltimore Orioles, and Washington Senators franchises, and Barnie is the reason the Pittsburgh Pirates are called the Pirates. He also helped develop NL franchises in Louisville and Buffalo, as well as strong International Association franchises in Albany and Columbus in the late 1870s. Upon his death the newspapers called him “the best known baseball man outside of Nick Young.”1

Barnie dreamed of creating a league to rival the National League. Five times he tried, including the American Association in 1882; he finally jumped on board a 1900 effort that helped make the American League possible. Barnie was arguably the first baseball figure to earn $50,000 in a season, and the first to generate $20,000 in ticket sales for a single game. Barnie promoted by making baseball a better sport, sitting on rules and schedule committees throughout his career. He was scandal-free and earned more while winning less.

Conversely, his faults as a tactical baseball manager, in the modern sense, were numerous. He overworked starting pitchers – even by the standards of his day – coveted speed over slugging, and rewarded loyalty to a fault. He was, in the parlance of the day, a “theatrical manager,”2 someone who ran baseball teams as if they were operating a theater company. He humiliated players with insults after errors as if they had forgotten their lines.

* * *

William Harrison Barney was born on January 26, 1851, the fourth of five children of Alexander Barney and the former Jean Gunn.3 In 1837, Barnie’s parents married and made the journey from Wick, Scotland, to America. They first settled on Barrow Street, New York City, but moved to Powers Street – now Third Avenue – in Brooklyn, around 18484. The 1880 census was the first to show the family name as “Barnie.” Alexander was a carpenter by trade, and built dozens of houses in Brooklyn, most notably the Washington Building, opposite City Hall.5

The eldest Barnie child, Alexander Jr., enlisted in the 14th Regiment – aka the “Red Legged Devils” – at the start of the Civil War. He survived the Second Battle of Bull Run, but his commander, Josiah Grumman did not. Alexander married Grumman’s widow, Helen Louise van Duyne, and took up residence in her tony Gold Street brownstone for a post-war military career capped by 25 years as a major in the New York National Guard Adjutant General Office.6 Alexander’s dress uniform is in the permanent collection of the New York Military Museum.7

William, 12 years younger than Alexander, suffered by comparison. A student at P.S. 15 in what is now Boerum Hill, Barnie caught baseball fever attending the Atlantic-Enterprise game on August 17, 1860. From atop the outfield wall, Barnie watched the young Enterprise players – who included Joe Start and Jack Chapman – nearly pull off an upset.8 Baseball history unfolded before Barnie: He was 11 years old for Jim Creighton’s death, 12 years old for the Eckfords’ undefeated season, and 13 for the rules change ending fair-bound catches. Barnie started one of the first school teams in America, played shortstop for the Junior Nassaus in late 1860s, and appeared for the amateur Brooklyn Nassaus in 1870.9 However, he seems to have been shunned by his family after 1873, when he quit a broker’s apprentice position on Wall Street10 to train and travel with Bob Ferguson’s Brooklyn Atlantics.11

Barnie’s proximity to Brooklyn’s Parade Grounds enabled him, and about 100 boys in the neighborhood, to develop professional-level baseball skills for the day. At the age of 19, Barnie may have been one of the top 25 catchers in America. While a handful of his Prospect Park buddies attained stardom with bigger teams, most fanned out across America in the late 1870s, to seed the growth of the sport from Maine to California, and share “inside baseball” with fans, players, and wide-eyed investors. Until 1882, a Brooklyn boy appeared on all but two major-league teams, and Billy Barnie became the most famous.

After traveling with the Atlantics, Barnie failed a tryout early in 1874 to be the backup catcher of the Philadelphia Athletics.12 He instead signed with Hartford and alternated catching duties with Scott Hastings. Barnie debuted on May 7 with a 3-for-3 performance off Baltimore’s Asa Brainard.13 His last hit was in civilian clothes as Hartford unexpectedly batted around.14 The rest of his season was poor. He was last in qualifying batters for average (.184) and led the league in strikeouts (13). No batting orientation has been found for Barnie, but his fair-foul hits went to left field, indicating a right-handed stance.15 It was reported that Hartford finished poorly because players “played seven-up late into the night.”16

Barnie signed with the Keokuk “Western” for 1875, also a National Association team. He took his Hartford sweetheart with him, 20-year-old Annie Eva Steich, after marrying her there during the first week of March.17 Ignorant of schedule-making, and marooned in mid-America without quality local rivalries, Keokuk disbanded with a 1-12 record after hosting the New York Mutuals on June 14, “while they could honorably pay their debts.”18 New York manager Nat Hicks signed Barnie and shortstop Jimmy Hallinan on the spot.

Barnie caught six games for New York that Summer, including Bobby Mathews’ 100th career loss, but his fortunes pivoted on two exhibition games. At Columbus, Ohio, on June 25, Barnie was loaned to the “Buckeye” club to make things interesting, and he was magnificent. Fans there feted him at the Neil House that evening with the presentation of a gift: a cane.19 In the second exhibition on July 2, Barnie took note of Paterson pitcher Ed Nolan, who copied Mathews’ stunt of throwing every first pitch 10 feet over the batter’s head.20 Barnie finished 1875 as one of six Brooklyn boys on the Louisville “Eagle”, the team that would become an NL franchise the following year. Prematurely balding at the age of 24, Barnie would become known as “The Bald Eagle.”21

In 1876, Columbus fans remembered their one-game hero, and Barnie was signed as captain of the nine. He brought along Nolan, who comprised a one-man pitching staff, later earning him the nickname “The Only” Nolan. For a Western team, Columbus played a record 81-game schedule in 1876, and in two seasons hosted seven of the eight NL teams. Columbus ran up a 7-12-2 record against them, and Barnie started almost every game with no mask, no gloves, and likely, just a mouthpiece.22 Once again, he used several Brooklyn neighbors to fill out the roster, including Frank Fleet, Herm Doscher, and Charlie Pabor. Barnie replaced James A. Williams as manager of the team on October 5.23 The 1876 Buckeyes gave Barnie a national reputation, although Indianapolis did steal Nolan for the last game of the year, when Barnie decided to play a game after contracts expired. It was reported as an “embarrassment” for Barnie – and proved to be a lesson.24

Williams became director of the Columbus club in 1877 and, along with H.D. McKnight, created the seven-team International Association for them to star in.25 But this season was a failure. Barnie started by handing the captainship to George Strief,26 making himself more of a business manager. Finding big Jim McCormick to be the principal pitcher, the team finished the IA schedule 8-11; it played .500 ball in 72 exhibitions. Fewer NL teams visited.

Barnie had an oft-mentioned personal streak of consecutive games catching. It ended at 84, presumably on August 3, with a badly dislocated finger.27 Although the finger was popped back in place and he did finish the game, Barnie proceeded to replace himself with the unknown Michael Kelly, and the future “King” jumped at the chance to earn $60 a month.28 Jaded Columbus fans referred to the team as “The Dummies”29 after Barnie’s refusal to accept a challenge from a teenaged deaf-mute team.30

Still injured, Barnie talked himself onto a brand-new Buffalo franchise on August 27, became manager eight days later, and led the team to a profitable 6-18 finish, after an unprofitable 3-11 start without him. Barnie was lambasted by the press for calling down players after errors while captain Art Cummings stood on the field. “A manifest impropriety,” one paper noted.31 One benefit of finishing so strongly was signing players from other teams that closed for the season early. Barnie signed Doc Bushong, Jack Glasscock, Montgomery Ward, Pud Galvin, and others, most in the last week of September. These signings, especially remembered in the decade of the 1880s, gave Barnie a remarkable, but probably undeserved, reputation as a scout.

Barnie was also one of the biggest promoters of ice baseball. 1878 was his fifth of 10 winters boosting that sport at Prospect Park with Henry Chadwick as an umpire and proponent.32 But while he was skating, Buffalo replaced him with Chick Fulmer, who went on to win the International Association pennant with “Barnie team.”33 Barnie organized “Barnie’s Nine,” which became a popular spring 1878 attraction at Brooklyn’s Parade Grounds. It featured Brooklyn Eagle reporter Will Rankin as pitcher and Chadwick as “prize-giver.”34

On or around April 20, Benjamin Douglas Jr., the Connecticut baseball mogul, appeared with blank contracts for his New Haven team. Seven Brooklyn boys, including Barnie and Candy Cummings, signed to complete Douglas’ nine35, and Barnie helped it wiggle into the International Association. Winless in six games, they rebranded themselves “Hartford” on June 1 but won only one of 10 before being kicked out of the Association on July 17,36 for shorting Buffalo guaranty money.37

Barnie and two other Hartford players then helped Billy Arnold set up an Albany team. This work included pulling up stumps for a new field on Rensselaer Island.38 Barnie appeared in the first five games before being replaced by Jim Keenan. Like Buffalo, Albany joined the Association in 1879 and won the pennant. It appears Barnie harbored a grudge against Arnold for many years.39

Offered $1,000 to head West,40 Barnie joined the San Francisco Knickerbockers after they signed blacklisted ace Ed Nolan, his old batterymate, when no one else could catch him.41 Barnie debuted on June 1, 1879, and quickly ascended to stardom. He stole “Grasshopper” Jim Whitney42 from the Omahas when they visited in August and appeared against the Rochester “Hop Bitters” and the White Stockings during their famous trips to “The Slope.” On August 22, Barnie was part of an early meeting of West Coast team owners who assembled to address poor ballpark conditions.43 On September 26, Barnie hit his only known career home run off future major-league pitcher Charlie Sweeney of the Californias, in a one-game playoff for West Coast honors.44

Barnie’s 1880 season was interrupted by a broken nose on May 29, and then curtailed when he jumped to a mining team in Virginia, Nevada, September 2.45 He was a ringer there for a month before returning to Brooklyn in October, celebrating his return by organizing a Nassau old-timers’ game on November 13.

Ferguson and Barnie created another reboot of the Brooklyn Atlantics in 1881, and Barnie soon made the team his. He created the 10-team Eastern Championship Association on April 11, at Earle’s Hotel near Chinatown, a league built to capitalize on the popularity of Jim Mutrie’s new Metropolitan team. Barnie made himself league secretary and his home address, 12 Bond Street, Brooklyn, became the league address.46 But the circuit failed as the Metropolitans’ staggering popularity allowed them to ignore the schedule. Barnie nevertheless ran Brooklyn to a 26-32 record over a 60-game schedule, taking them on a successful September road trip that included Philadelphia, Louisville, St Louis, and Cincinnati.47

Barnie’s ulterior motive for that road trip was to form another new league. On November 2, 1881,48 at the Gibson House in Cincinnati,49 clubs from the cities he visited signed up along with Barnie’s Atlantics – pending capitalization – and the American Association was born. Barnie credited Horace Phillips’ help in making the Association possible.50 Unfortunately, his Atlantics never received this funding, and on March 13, 1882, the AA was completed with Baltimore replacing Brooklyn.51 Barnie received “first right of refusal” if any AA team disbanded.52 He then ran his “Brooklyn Atlantics” again as an independent team for 36 games, but ditched his men on July 22 to manage Al Reach’s independent Philadelphia’s. Philadelphia immediately went on a 20-8 tear through the first celebration of Labor Day, with Barnie himself alternating catching duties with Joe Straub. Seeing Philadelphia’s attendance spike, NL owners rushed there to hold a secret meeting opening the door for New York and Philly to replace Worcester and Troy.5354

Poised to be the first manager of the Phillies NL franchise, Barnie instead parted amicably with Reach and claimed the Baltimore AA territory from a near-bankrupt Henry Myers. Barnie was announced as Baltimore’s owner on October 23. Loyal and thankful, it was likely Barnie who helped NL owner Reach get the baseball concession for the AA. Barnie took on a partner, Alphonso T. Houck, from the family that owned the lease on Newington Park. Houck was an eccentric sort, quick to hand out cigars and calamus root after a win.55 Houck’s talent was plastering Baltimore proper with event advertising. He was also a member of the Baltimore civic group, the “Order of the Oriole,”56 and may have named the team. Barnie sat on the AA’s rules and schedule committees and met with NL directors to negotiate peace. On January 27, 1883, Barnie was one of four signers of the original multi-league reserve rule,57 a baseball contract staple until challenged by Curt Flood 86 years later.

Barnie struck gold. Spring exhibition games against NL teams brought all the great players to Baltimore fans, and a blue-collar, rowdy element found a safe place for summer. Barnie caught part-time, with strips of lead inside his small gloves,58 and captained for the last time. After a 12-31 start, he stepped down, appointing Dave Rowe captain.59 Although Baltimore finished last, Barnie cleared well over $50,000. He managed from the bench60 or a chair behind home plate.61 He was so trusted that he even umpired some Baltimore games during his nine-year tenure as manager. Barnie also began producing theatrical events, managed the Jeannie Winston Company in the winter,62 and also used his players in his off-season skating rinks.6364

The Union Association and the Eastern League invaded the Baltimore market in 1884, and Barnie took on debt despite a first-division finish. After the other Baltimore competitors tanked, thankful Oriole players took up a collection and presented Barnie with a $300 ring for his “vexatious” efforts – the first ring awarded in baseball to signify triumph.65 Barnie also was in, and likely initiated, the first player trade on February 29. He bypassed his own reserve rule by having Cleveland release Tom York “to Baltimore” while Barnie released Cal Broughton in what the papers called “an exchange of players.”66

By February 1885, Barnie rose to AA delegate along with Brooklyn’s President, Charlie Byrne. The two – who were the same height and sometimes reported to be related67 – became friends. They may have put up the first “No Gambling” sign in the player’s clubhouse together.68 They also conspired for years to protect the AA against erratic St Louis Browns owner Chris Von der Ahe.69

In 1886, the same year that Barnie invented the coaching box,70 the Baltimores batted .204 and slugged .258, both all-time worsts for big-league teams that completed their schedule. “If ill luck ever followed a man, it has followed me,” Barnie said. “But I don’t mean in a financial sense.”71

Possibly under the thumb of Byrne, Newark manager Charlie Hackett sold Barnie the pick of his 1886 minor-league champions for 1887. Baltimore pushed St Louis through early July, and the pressure was on. But Barnie left the team and filled in as an AA umpire for a game in Brooklyn as Baltimore was about to get swept.72 Barnie returned to the team the same week he missed his parent’s grand 50th wedding anniversary on August 29.73

On rules committees, that year Barnie pushed for “three strikes and out” and the end of counting walks as hits. Barnie won both battles, the first to help his own pitcher, “Phenomenal” Smith, who could not get that fourth strike over the plate,74 and the second against no less a figure than Harry Wright.75

Although Barnie bought out Houck in December 1884,76 he began borrowing from 38-year-old Baltimore brewery owner Harry Von der Horst later in 1885.77 These loans turned into equity, and on October 27, 1890, a corporate charter headed by John Waltz was created for the Baltimore club.78 This is what eventually pushed Barnie out. The lack of confidence arose in part because Barnie pulled Baltimore out of the AA on November 29, 1889,79 a move coordinated with his scheme to combine with Washington and play in two home cities.80 This came 17 days after the famous AA meeting in New York City where Cincinnati and Brooklyn quit to (eventually) join the NL, a walkout ending12 hours of deadlocked voting for association president. Presumably unaware that Cincinnati and Brooklyn had secured NL berths, Barnie followed them out that day; a few days later he burned his bridges with Von der Ahe in a St. Louis Post Dispatch interview.81

League-less, Barnie’s player contracts were argued to be void,82 and the Philadelphia Players League team scooped the best players up. Philadelphia Athletics director Jacob E. Wagner commented that “Barnie is insane, and was sent to the Maryland Insane Asylum.”83 This led reporters to converge on Barnie’s Baltimore home at 12 East Second Street, North, at 2 A.M on December 5, asking Barnie if he was crazy.84 He quickly denied it, yet the reporters said: “But the Philadelphia Ledger has positive information you are insane.”85

“This is no time for fun.” Barnie said. From a window in his PJ’s, Barnie promised to “show the base-ball world before long that he had not yet lost his senses.”86

When he announced that Baltimore would replace Lowell in the Atlantic Association, Atlantic Association officials scoffed.87 But exactly that happened.88 Possibly with money lent by Byrne, Barnie also bought the Worcester franchise,89 and got his old player, Tommy Tucker, to jump back to the NL, telling him his PL contract was signed “on a Sunday”90 – a return favor for Byrne because it hurt John Montgomery Ward’s PL Brooklyns. Barnie then sued the editor of the Philadelphia Public Ledger, George Childs, and Jacob Wagner, for $20,000,91 later netting an amicable settlement.

Baltimore and New Haven staged a bang-up two team race that hurt fan interest in the other six Association cities. When Jersey City disbanded, Barnie also disbanded his Worcesters, and hustled in the Pennsylvania towns of Harrisburg and Lebanon to balance the schedule.92 Barnie named cities that were off-limits to Harrisburg’s African-American player, Frank Grant, but kept him on the roster.93 However, on August 14, 1890, Barnie received a telegram from Charlie Morton, asking if he’d bring Baltimore back to the AA to replace the financially failing Brooklyn Gladiators. Barnie accepted.94 On Wednesday, August 27, Baltimore returned to the AA and hosted St Louis. Barnie and Von der Ahe shook hands behind home plate like old friends.95

One week later, Barnie did another favor for Byrne,96 using his brand-new AA vote to shoot down a proposed PL-AA “World’s Series.” The other 15 club owners voted “yes.”97 More significantly, on September 5, the Philadelphia Athletics notified AA president Zach Phelps that bankruptcy was imminent. A swarm of managers and scouts converged on Philly to sign up their star players. Barnie volunteered to “take charge of the franchise,” holding stockholder meetings and assuring the players that all would be well.98 A wolf in sheep’s clothing, Barnie allowed the team to default while sequestering Sadie McMahon and Wilbert Robinson at the Continental Hotel. He signed them both minutes after midnight on September 17, 1890, as their contracts expired.99 Barnie also found Curt Welch in the crowd at the Boston-Philadelphia PL game, before the Wagners and their security did, and got a verbal agreement from him, promulgated later.100 Barnie did err by not reserving Harry Stovey and Lou Bierbauer, two Philadelphia AA players who had been stolen by the PL. This oversight would prove fatal to the American Association.

In October Barnie was part of the six-man, NL-AA committee to “make peace” with the PL, at New York’s Fifth Avenue Hotel.101 Montgomery Ward, the leader of the players’ movement, was famously ordered to leave the meeting, before the NL dangled buyouts to greedy PL owners. Before his ejection, Ward turned to Barnie, saying: “You were a player once, Mr. Barnie. Now I beseech you not to thrust us from this room.” Barnie was silent. Ward and the players left, and the PL owners capitulated.102

During this tumult, Barnie ascended to the office of AA vice-president on November 24.103 One of his first orders of business was expelling the old Philadelphia AA franchise and awarding a new, debt-free one to the Wagner brothers.104 Two months later, on January 23, 1891, Pittsburgh’s NL club signed Bierbauer from the remnants of the Brooklyn PL franchise.105 Bierbauer, as mentioned, should have been reserved by the Philadelphia AA franchise that September, but wasn’t. Nine days later, Boston signed Stovey with the same reasoning.106 Hearing that Cleveland was about to steal Maryland youngster Clarence Childs from him, Barnie promised to speed off to intercept the second baseman at the Syracuse train station, claiming that Childs’ contract was valid.107 Barnie was enraged when Cleveland signed “the Cupid,” shortly after Valentine’s Day.108

AA and NL reps were meeting at the Auditorium Hotel in Chicago to hash out all these differences. The NL had one vote, the AA had one vote, and AA president Allen Thurman, son of a U.S. congressman, was entrusted with the tie-breaking vote. Thurman shocked the room by voting with the NL.109 For “stealing” Bierbauer from Barnie, the Pittsburgh team has been called the “Pirates” ever since. Emotions ran high. After midnight, on Wednesday, February 18, 1891, at New York’s Murray Hill Hotel, Barnie staged an AA coup, deposing Thurman and acting as AA president for about 18 hours.110 During this short tenure, Barnie wrote a letter to the NL pulling the AA from the National Agreement.111 Players, and telegrams from players, filled the hotel lobby that day, with Dan Brouthers and King Kelly signing AA contracts. Barnie stormed the NL meeting two weeks later and signed George Van Haltren and Sam Wise, shouting his act to those in the lobby. “Are you still alive?” NL owners shouted back.112

On March 9, Al Johnson, who had virtually been gifted the Cincinnati AA franchise for his Cleveland PL stake, sold out to NL interests.113 Barnie spent two weeks in Cincy, rebuilt Pendleton Park, and set up a Cincinnati team, assigning King Kelly to captain it.114 Barnie’s Baltimores did well, starting the year 22-10, opening Oriole Park on May 11, and then debuting John McGraw in August. Barnie signed McGraw sight unseen after Von der Ahe called him “too short.”115 But Barnie’s Baltimore era came to an end on September 28 during a quarrel with Von der Horst, who wanted pitcher Egyptian Healy released.116 Barnie was announced as manager of the Philadelphia Athletics almost immediately, the very same Wagner brothers-owned franchise which Barnie had helped award them one year earlier.117 Barnie did calm down and sat on the Baltimore bench for the team’s final six games.118 The Baltimore Elks, of which Barnie had been a member for many years, gave him a heartfelt testimonial before star players from across the Northeast staged a benefit game on his behalf on October 15.119

Barnie went to work for the Wagners, signing Danny Richardson, Roger Connor, and William “Dummy” Hoy. NL Phillies owner John Rogers chortled: “Regularly every year he wins the championship… in Winter.”120 In response, Barnie told a reporter, “The Phillies have won the championship a lot of times, I don’t think.”

Barnie also steered all the stock of NL players to the Wagners.121 When the AA finally “merged” with the NL in Indianapolis on December 17, 1891, the Wagners had enough NL stock – and cash – to claim the Washington franchise.122 Barnie was made manager but was quickly fired in April 1892 when J. Earle Wagner insisted that rookie Patsy Donovan be put on the team. Barnie publicly skewered Wagner after a Donovan misplay lost the second game of the season.123 Idle, Barnie and his wife moved from Baltimore to Brooklyn,124 and Barnie umpired a benefit game for Hub Collins in late May.125

Less than a week later, he jumped back into management and made a bid to save Frank Robison’s Fort Wayne club in the Western League.126 Unfortunately, Barnie’s old friend James A. Williams, the league president, was working the so-called “millennium plan,” whereby teams could receive players only from the league office.127 The Western folded 13 days into the split season’s second half. Barnie disbanded the Fort Wayne franchise on July 7 and was handed the Minneapolis club,128 which he ran for four days without playing a game. An NL umpire sinecure, given to Barnie on August 10, was fight-filled and lasted two weeks.129

On New Year’s Eve, Barnie signed to manage the 1893 Louisvilles. Chadwick wrote, incorrectly, that “Billy Barnie(’s)… ability as a manager has never been properly tested, from the simple fact that he has never had entire control of any team.”130 Louisville was horrible. Barnie publicly blamed the players and shouted them down at postgame meetings.131 In October, Barnie was chosen to manage a team of Eastern stars through California, and this was a nationally recognized success.132

After this trip, Louisville ownership could not fire Barnie; he got a second season, redeemed only by the June 30debut of future Hall of Famer Fred Clarke. “Mr. Barnie is a nice man,” the Louisville Journal-Courier finally wrote, “but he is certainly a dead failure as the manager of a base-ball team.”133 One Barnie trick was laying out the players’ uniforms, end to end, on the basepaths at night under a full moon for good luck.134 It didn’t work. The year ended with donation boxes at the gates, for what few fans straggled in.135

For the last few months of 1894, Barnie was selling investors and players on the idea of a “New AA,” an endeavor for which the NL blacklisted him, Fred Pfeffer, and Al Buckenberger, October 18.136 There were tense moments as Barnie was given the opportunity to sign a pre-written confession and get back in the establishment’s good graces. Barnie pointed to his old friend Byrne: “If I go down, I will pull others with me!” 137 The conservative New York Clipper had written that six Baltimore losses at the end of 1889 – because Barnie used players in their wrong positions – helped Brooklyn win the pennant.138 Nothing came of these misadventures, and the three men were exonerated.

Barnie managed Scranton in 1895 and Hartford in 1896, purchasing the latter team with his lawsuit settlement money and final Baltimore equity payment.139 Scranton finished terribly, with Barnie missing time after being injured in the collapse of the Elks’ Atlantic City convention building on July 10.140 Barnie’s Hartfords nearly gave him what would have been his only career first-place finish. Hartford was leading by half a game on the final weekend when Newark’s manager – and Barnie’s old captain – Tom “Oyster” Burns sneakily added a Saturday doubleheader against the next-to last place Athletics. Newark swept the twin bill when Ned Garvin threw a season ending no-hitter. Barnie protested, but league president Sam Crane had been in the stands for the Garvin game and stood up to pronounce Newark the champions.141 “I was euchred out of the pennant.” Barnie said.142

True friend Byrne, impressed by Hartford’s finish, offered Barnie the Dodger managership for 1897,143 making him the only Brooklyn-born manager in club history.After Barnie’s death, a poor finish was explained by the Brooklyn Eagle, which reported that the team had been truly run by a clique which included one of Barnie’s favorite players, Billy Shindle.144

That fall, once again Barnie took an all-star team to California, opening West Coast play with a “parade of ballplayers” up Market Street in San Francisco on November 6. Barnie and Boston manager Frank Selee rode in an open coach followed by a banner: “The Genius of Baseball.”145 The opening game netted over 180 pounds of mined silver and gold that made the entire 50-game trip a success.146 It was likely the first baseball game to bring in $20,000 on ticket sales alone.

Unfortunately, Charlie Byrne’s death in early 1898 made Charlie Ebbets – never a Barnie proponent – the new Brooklyn president. Ebbets terminated Barnie with a 15-20 record on June 6.147 Non-playing managers were “excess baggage,” Ebbets said.148

On June 20, Barnie signed with the near-bankrupt, last-place team in Springfield, Massachusetts, of the Eastern League.149 At the time, the players were on strike.150 Barnie and league president Pat Powers ended the stoppage with authoritarian methods. Barnie subsequently drove the team to the first division by mid-July before hitting an August slump.

That fall, Barnie pushed for the formation of another new major league: the Union League.151 However, Nick Young quickly awarded any geographic claims that Barnie had to the Eastern League.152 Irrepressible, Barnie formed a roller polo team in Stamford.153 He also helped schedule a fledgling Eastern District “National Basketball League.”154 Barnie announced, prophetically, that the NL would contract to eight clubs.155 He retreated to Hartford and pushed for yet another new major league in 1899 – the “New AA,” which had already been created at Cap Anson’s Chicago billiard parlor.156 To combat this move, NL owners befriended Western League president Ban Johnson, allowing expansion into Chicago and Cleveland, while Johnson agreed to use the Spalding ball.157

This “New AA” failed on February 15, 1900, when John McGraw met with Philadelphia investors and came away unimpressed.158 Brooklyn skipper Ned Hanlon was happy to take him and Wilbert Robinson back in (though the Superbas would soon sell both players’ rights to the St. Louis Cardinals). The NL ratified contraction on March 10, 1900 – too late for any competitor league to take advantage.159 Barnie applied for the Baltimore franchise but, in the end, rejected Young’s $4,300 franchise fee just before Opening Day.160

Barnie doted on his Hartford team, but was unable to shake his “spring cough” that June.161 He took leave of Hartford on July 2 to rest at home,162 but made an ill-advised trip to Atlantic City, again for the Elks convention.163 Under a doctor’s care in Atlantic City, Barnie returned on July 13 and was pushed home in a wheelchair by Hartford mayor Al Harbison to the house of his sister-in-law’s family, the Naedeles, on 51 Mahl Avenue. 164 Barnie passed away two days later. Bronchitis had led to pneumonia, doctors said.165

Barnie is buried in the Paterson gravesite in Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery. John Paterson was born in Inverness, lived with the Barnie family, and became a successful plumber and coal merchant 166 on Nostrand Avenue.167 Paterson married Jeanie, Billy Barnie’s eldest sister, around 1862, and their three daughters, Annie, Margaret, and Jennie, are listed below them on the right side of the headstone. The top left of the headstone is graced by Barnie’s parents, himself, and his two younger sisters, Isabell and Charlotte. Charlotte married James Newcomb in 1882 and ventured to Minnesota; her only daughter, May, is chiseled below on the headstone as the 11th of the family. Barnie’s brother, Major Alexander Jr., is in a military section of Green-Wood about two city blocks east.

Barnie’s siblings produced five daughters who never married. The last four to survive, all shown on the Paterson headstone, shared an apartment at 1307 Pacific Street, Brooklyn.168 One by one, they passed away there until Jennie, daughter of Barnie’s older sister Jeanie, died at 98 in June of 1962. In 1904, Barnie’s widow Annie remarried in Hartford, to Newfoundland-born John M. Drake,169 a memorial mason and stone carver.170 Early in 1907 she suffered a stroke and passed away after 15 months of paralysis.171 Drake dutifully sculpted a gorgeous headstone for her with the famous Barnie name.172

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Lamb and Rory Costello and checked for accuracy by SABR’s fact-checking team.

Photo credit: Trading Card Database.

Notes

1 “William Barnie Dead,” New York Times, July 16, 1900: 7.

2 “The Time for Action,” Baltimore Sun, July 21, 1890: 3.

3 “Maj. Barnie Dies in His 82d Year,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 23, 1919: 18.

4 “Maj. Barnie Dies in His 82d Year.”

5 “Obituary,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April 8, 1897: 3.

6 “Maj. Barnie Dies in His 82d Year.”

7 Photo in post on Civilwartalk.com, September 24, 2017 (https://civilwartalk.com/threads/14th-brooklyn-84th-new-york-volunteer-infantry-red-legged-devils-not-just-a-cool-uniform.138885/).

8 “A Long Base Ball Career,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, January 30, 1898: 9.

9 “The World of Sports Reviewed by an Expert,” Standard Union (Brooklyn), August 25, 1900: 12.

10 “The Late Billy Barnie,” Leon (Iowa) Reporter, August 30, 1900: 4.

11 “Wm Barnie,” New York Clipper, June 11, 1892: 219.

12 “Baseball” (see: Barnie the catcher…) New York Clipper, February 14, 1874: 362.

13 “Base Ball,” Hartford Courant, May 8, 1874: 2.

14 “In Base-Ball’s Early Days.” Baltimore Sun, April 23, 1890: 6.

15 “The Diamond Field” Chicago Inter-Ocean, May 28, 1874: 8.

16 “Sporting Items” (see: Baseball), Brooklyn Daily Times, June 2, 1874: 4.

17 “Sports And Pastimes,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 12, 1875: 4.

18 “Gossip” (see: We Disband…), St Louis Globe Democrat, June 22, 1875: 3.

19 “Mutuals vs. Buckeyes – Game No. 2,” Daily Evening Dispatch (Columbus, Ohio), June 26, 1875: 3.

20 “Ball And Bat (see: In the Game at Paterson…), St Louis Globe Democrat, July 9, 1875: 8.

21 “News And Comment,” Sporting Life, February 22, 1896: 4.

22 “Dust From the Diamond,” San Francisco Call, October 30, 1897: 10.

23 “The Great Game Today,” St Louis Globe Democrat, October 14, 1876: 8.

24 “The City. Bat And Ball,” Indianapolis Sentinel, October 18, 1876: 7.

25 “James A. Williams,” New York Clipper, March 19, 1892: 25.

26 “Base Ball,” Daily Evening Dispatch, April 18, 1877: 4.

27 “Base Ball,” Daily Evening Dispatch, August 4, 1877: 4.

28 “General Sporting Notes” (see: Baseball), Passaic Daily News, October 16, 1896: 5.

29 “Local Mentions” (see: The Buckeye Club), Daily Evening Dispatch, August 27, 1877: 4.

30 “The Buckeye Club,” Daily Evening Dispatch, July 6, 1877: 4.

31 “Too Many Errors,” Buffalo Morning Express, September 29, 1877: 4.

32 “Baseball on Ice…,” New York Evening Telegram, December 31, 1878: 4.

33 “Bisons Did Not Play,” Buffalo Morning Express, August 4, 1898: 10.

34 “Base Ball,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 10, 1878: 3.

35 “Base-Ball Notes,” Buffalo Morning Express, April 25, 1878: 4.

36 DeWitt’s Base Ball Guide for 1879, St. Paul Book and Stationery Co.: 55.

37 “Base-Ball Notes,” Buffalo Morning Express, July 26, 1878: 4.

38 Albany Evening Journal, August 3, 1878: 3.

39 “Syracuse Gets the Place,” New York Daily Tribune, February 21, 1894: 4.

40 “Base Ball” (see: The Next Season…), Oakland Tribune, September 26, 1879: 3.

41 “Base Ball Notes” Sacramento Bee, June 2, 1879: 3.

42 “Base-Ball Matters,” San Francisco Examiner, March 8, 1880: 3.

43 “Base-Ball,” San Francisco Examiner, August 22, 1879: 3.

44 “Base Ball Notes,” Sacramento Weekly Bee, September 27, 1879: 3.

45 “Base-Ball Matters,” San Francisco Examiner, September 3, 1880: 3.

46 “Base-Ball Men in Council,” New York Times, April 12, 1881: 8.

47 “Wm Barnie,” New York Clipper, June 11, 1892: 219.

48 “Born,” Cincinnati Enquirer, November 3, 1881: 5.

49 “Daily Enquirer,” Cincinnati Enquirer, November 2, 1881: 2.

50 “A Long Base Ball Career,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, January 30, 1898: 9.

51 “Sporting Matters,” Cincinnati Enquirer, March 14, 1882: 2.

52 “A Long Base Ball Career,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, January 30, 1898: 9.

53 “Base-Ball Matters,” Chicago Tribune, October 2, 1882: 3.

54 “New League Clubs,” Philadelphia Times, September 23, 1882: 2.

55 “From Baltimore,” Sporting Life, June 18, 1884: 6.

56 “The Oriole In North Carolina,” Baltimore Sun, September 9, 1882: 6.

57 “Base Ball Convention,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, February 19, 1883: 4.

58 “Almost A Defeat,” Pittsburgh Post Gazette, May 12, 1883: 5.

59 “Baltimore Notes,” Sporting Life (Philadelphia, PA), July 22, 1883: 6.

60 “Echoes Of the Game,” Boston Globe, June 25, 1891: 3.

61 Hugh S. Fullerton, “On the Screen of Sport,” Duluth Herald, August 27, 1921: 10.

62 “Personal Paragraphs,” Evening Journal (Wilmington, Delaware), November 15, 1888: 3.

63 “From Baltimore,” Sporting Life), October 22, 1884: 6.

64 “From Baltimore,” (See; Next week will end…) Sporting Life, October 15, 1884: 6.

65 “From Baltimore,” (See: At the close of…) Sporting Life, October 15, 1884: 6.

66 “Base Ball Gossip,” Harrisburg Telegraph, March 1, 1884: 1.

67 “Barnie Succeeds Dave Foutz,” Topeka State Journal, October 15, 1896: 3.

68 “Our Champions,” Brooklyn Standard Union, October 25, 1889: 3.

69 “A Secret Combine,” Pittsburgh Dispatch, April 3, 1892: 6.

70 “The World of Sport,” Cleveland Leader, June 10, 1886: 3.

71 “Chats With Baseball Men,” New York Tribune, December 27, 1886: 8.

72 “A Kicking Nine,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 27, 1887: 4.

73 “A Golden Wedding,” Brooklyn Daily Times, September 3, 1887: 6.

74 “The Sporting World,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 1, 1887: 8.

75 “Baseball” (see: Notes of The Game), Norfolk Virginian, April 26, 1887: 1.

76 “Baseball,” New York Clipper, December 6, 1884: 603.

77 “Wm. Barnie Resigns,” Baltimore Sun, September 29, 1891: 6.

78 “Baltimore Incorporates,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, October 28, 1890: 3.

79 “The American Association is in A Very Bad Condition,” Philadelphia Inquirer, November 15, 1889: 6.

80 “Barnie’s Latest Dicker,” Louisville Courier, November 28, 1889: 1.

81 “Barnie On President Von der Ahe,” St. Louis Post Dispatch, November 18, 1889: 8.

82 “Speas And His Big Jump,” (see: “When they drew out…”) Kansas City Star, November 18, 1889: 3.

83 “Manager Barnie’s Libel Suits,” Baltimore Sun, August 5, 1890: 4.

84 “Manager Barnie Says He Is All Right,” Baltimore Sun, December 5, 1889: 6.

85 “Barnie Not Insane, But Angry,” Chicago Inter Ocean, December 7, 1889: 6.

86 “A Fake,” Cincinnati Enquirer, December 6, 1889: 2.

87 “Lowell Ball Gossip,” Boston Globe, December 21, 1889: 5.

88 “Denies He Has Put Up a Job,” Cincinnati Enquirer, December 29, 1889: 6.

89 “Bought The Worcester Franchise,” Brooklyn Eagle, February 2, 1890: 18.

90 “Comes Easy Now,” Boston Globe, January 10, 1890: 2.

91 “Games To Be Played” (see: William Barnie Manager), New York Clipper, August 9, 1890: 347.

92 “Lebanon Admitted,” The York Dispatch, July 31, 1890: 1.

93 “Harrisburg Still Doubtful,” Baltimore Sun, July 21, 1890: 3.

94 “Back To the Old Love,” Baltimore Sun, August 19, 1890: 3.

95 “Base-Ball Notes,” Baltimore Sun, August 28, 1890: 3.

96 “Notes of the Ball Field,” (column 3: “A dispatch from…”) Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 4, 1890: 2.

97 “Secret Base-Ball Conference,” Baltimore Sun, September 4, 1890: 6.

98 “The Athletic Club,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 16, 1890: 3.

99 “Off For the West,” Baltimore Sun, September 19, 1890: 4.

100 “Off For the West.”

101 “Base-Ball Compromise,” Baltimore Sun, October 23, 1890: 7.

102 “Base Ball Comment,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 27, 1890: 3.

103 “Athletics Expelled,” Philadelphia Inquirer, November 25, 1890: 3.

104 “Base Ball Comment,” Philadelphia Inquirer, November 30, 1890: 3.

105 “Barnie Is Really Mad,” Pittsburgh Post, January 28, 1891: 6.

106 “Stovey With the League,” Pittsburgh Post, February 7, 1891: 6.

107 “Baseman Childs’ Case,” (Boston) Sunday Herald, February 15, 1891: 6.

108 “Childs Is Signed,” Cleveland Leader, February 17, 1891: 6.

109 “Must Go to Pittsburg,” Chicago Tribune, February 15, 1891: 6.

110 “And War It Is,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, February 19, 1891: 5.

111 “And War It Is.”

112 “‘Nothing New’ Say The Magnates,” New York Herald, March 5, 1891: 9.

113 “Sold Out,” Cincinnati Enquirer, March 10, 1891: 1.

114 “Secured New Grounds,” Pittsburgh Dispatch, March 14, 1891: 6.

115 “Von der Ahe Figured M’Graw Might Make a Good Jockey,” The Sporting News, Dec. 31, 1925: 3.

116 “Wm. Barnie Resigns,” Baltimore Sun, September 29, 1891: 6.

117 “Manager Barnie Signed,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 29, 1891: 3.

118 “A Game Forfeited,” Baltimore Sun, October 6, 1891: 6. (Note Barnie protest here.)

119 “Expert Ball-Players,” Baltimore Sun, October 16, 1891: 6.

120 “Director Abell Has Withdrawn,” Philadelphia Inquirer, November 11, 1891: 3.

121 “A New York Club Not Yet Assured,” Philadelphia Inquirer, November 10, 1891: 3.

122 “The League United for Its Scheme,” Philadelphia Inquirer, December 16, 1891: 3.

123 “Manager Barnie Deposed,” St Louis Globe-Democrat, April 19, 1892: 9.

124 “Base Ball” (see: Ex-Manager James Maculler), Washington Evening Star, May 24, 1892: 7.

125 “Sporting News,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, May 30, 1892: 4.

126 “Barnie Goes to Fort Wayne,” Lincoln Journal Star, June 3, 1892: 8.

127 “Baltimore Bulletin,” The Sporting Life, July 2, 1892: 4.

128 “The Western Still Lives,” Pittsburgh Post Gazette, July 9, 1892: 6.

129 “Another Day of Ease,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 26, 1892: 2.

130 “Bicycle And Base Ball,” Louisville Courier Journal, January 15, 1893: 5.

131 “Shake-Up Promised,” Louisville Courier Journal, June 14, 1893: 5.

132 “Throws Swift Ball,” Evansville Courier and Press, July 17, 1894: 6.

133 “Louisville’s Shame,” Louisville Courier Journal, September 30, 1894: 8.

134 “Barnie’s Potent Charm,” Louisville Courier Journal, July 10, 1893: 6.

135 “Flowers And Telegrams,” Louisville Courier Journal, September 27, 1894: 5.

136 “The Big League,” Buffalo News, November 19, 1894: 4.

137 “Barnie Still in The Fold,” Omaha World Herald, December 21, 1894: 2.

138 “Baseball” (see: Manager Buckenberger…), New York Clipper, December 10, 1892: 645.

139 “News And Comment,” The Sporting Life, February 1, 1896: 4.

140 “Crash!” Buffalo Evening News, July 11, 1895: 1.

141 “Newark Wins Two Games,” Hartford Courant, September 14, 1896: 1.

142 “An Atlantic Row,” The Sporting Life, September 19, 1896: 7.

143 “Barnie Of Brooklyn,” The Sporting Life, October 24, 1896: 4.

144 “Cliques In Base Ball Despite Players’ Denials,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, January 25, 1901: 14.

145 “Parade Of Baseball Stars Who Will Play Here Tomorrow,” San Francisco Chronicle, November 6, 1897: 8.

146 “Return From the West,” Washington Evening Star, December 20, 1897: 9.

147 “Griffin Is Manager Now,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 7, 1898: 5.

148 “Barnie Boiling-Mad,” The Sporting Life, September 10, 1898: 1.

149 “Springfield O.K.,” Buffalo Morning Express, June 21, 1898: 9.

150 “Barnie To Manage Springfield Club,” Chicago Tribune, June 21, 1898: 4.

151 “It Rained Again,” Buffalo Courier, August 4, 1898: 3.

152 “Billy Barnie Makes a Statement,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, January 26, 1899: 12.

153 “Polo Players Hold Out,” Philadelphia Inquirer, December 22, 1898: 4.

154 “Basket-Ball,” New York Tribune, November 3, 1898: 4.

155 “Wise Barnie,” The Sporting Life, September 3, 1898: 4.

156 “Confer With Anson,” Chicago Inter-Ocean, October 9, 1899: 8.

157 “Strong Compact Made,” Buffalo Courier, October 13, 1899: 2.

158 “New Association Never Saw Life,” Philadelphia Inquirer, February 16, 1900: 10.

159 “Eight Club Circuit,” Indianapolis News, March 10, 1900: 3.

160 “May Give Up Baltimore,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 31, 1900: 6.

161 “Manager Barnie Dead,” Hartford Courant, July 16, 1900: 8.

162 “Notes Of the Game,” Hartford Courant, July 3, 1900: 2.

163 “Manager Barnie Sick,” Hartford Courant, July 10, 1900: 5.

164 “Mr. Barnie Brought Back,” Hartford Courant, July 14, 1900: 7.

165 “Death Of William Barnie,” Meriden Journal, July 16, 1900: 10.

166 “John Paterson,” Brooklyn Citizen, January 29, 1908: 5.

167 US Census Records, 1840 through 1950.

168 “Mary H. Kennedy Leaves $459,196,” Brooklyn Daily Times, November 19, 1930: 40.

169 “Obituary, Mrs. Annie E. B. Drake,” Hartford Courant, April 6, 1908: 14.

170 “Business Cards,” Hartford Courant, October 24, 1907: 7.

171 “Obituary, Mrs. Annie E. B. Drake,” Hartford Courant, April 6, 1908: 14.

172 Annie Drake page on Findagrave.com, accessed September 16, 2022 (https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/42738117/annie-eva-drake).

Full Name

William Harrison Barnie

Born

January 26, 1851 at New York, NY (USA)

Died

July 15, 1900 at Hartford, CT (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.