Bob Hendley

Among the classic baseball records, Ty Cobb’s 4,191 hits and Babe Ruth’s 714 home runs have fallen, but Cy Young’s 511 victories remain ingrained in the pantheon. And yet, many modern-day fans have shed their fascination with pitchers’ wins, understanding that the sport is a team-wide effort, rather than an individual competition. However, when a David takes on a Goliath, victories are still the traditional passage to accolades and remembrances. Such is the story of Bob Hendley, forever intertwined with Sandy Koufax. Two 1965 games and elbow injuries connect the two southpaws. Koufax retired early, choosing a life without pain over additional years in the majors. Hendley faced the choice even earlier — his elbow caused problems before he had even reached 20 years of age.

Among the classic baseball records, Ty Cobb’s 4,191 hits and Babe Ruth’s 714 home runs have fallen, but Cy Young’s 511 victories remain ingrained in the pantheon. And yet, many modern-day fans have shed their fascination with pitchers’ wins, understanding that the sport is a team-wide effort, rather than an individual competition. However, when a David takes on a Goliath, victories are still the traditional passage to accolades and remembrances. Such is the story of Bob Hendley, forever intertwined with Sandy Koufax. Two 1965 games and elbow injuries connect the two southpaws. Koufax retired early, choosing a life without pain over additional years in the majors. Hendley faced the choice even earlier — his elbow caused problems before he had even reached 20 years of age.

Charles Robert Hendley was born on April 30, 1939 in Macon, Georgia, a midsized city 89 miles from Atlanta. His father, W.T. Hendley, worked at the Robins Air Force Base as a civil servant until his retirement. The elder Hendley played semiprofessional baseball while working in a local textile mill. Unlike his son, W.T. Hendley was right-handed; like his son, he took to the pitching mound but saw injuries derail his career. Bob Hendley would credit his father for teaching him the knuckle curve ball and proper pitching mechanics. His mother, Nellie, was known for her cooking and sewing while caring for Bob and his elder brothers Billy and Ronnie. The three siblings spent much of their time outside, playing sports, hunting, and fishing.

Bob attended Lanier High School, starring in track, basketball, and baseball. The third was his best sport, as he led his team to the state championship. While scouts were aware of his prowess, he made sure they underlined their notes by striking out every man he faced — nine in three pristine innings — at Georgia’s North-South high school all-star game.1 The performance was the exclamation point on a superb schoolboy career that included 16 wins, 204 strikeouts, and three no-hitters at a time when his peers were mostly concerned about the prom.

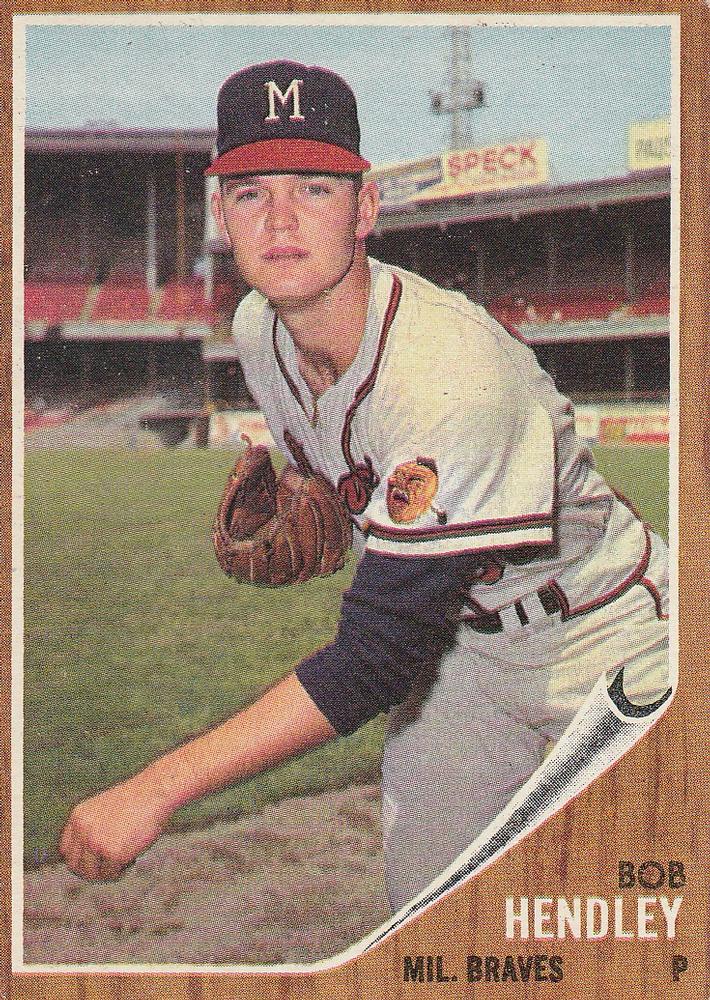

Hendley was offered a baseball and basketball scholarship by the state’s flagship institution, the University of Georgia. However, he opted to sign a professional contract with the Milwaukee Braves on August 17, 1957. He spent most of his time in 1958 with Cedar Rapids of the Illinois/Indiana/Iowa League (Class B), a strong club that led its circuit in pitching en route to the title. The young man won 14 games against only five defeats, posting a 2.81 ERA and 8.1 strikeouts per nine innings. He also appeared in eight games for Jacksonville of the South Atlantic League, but complete records of the season were not kept for all players.

A promotion to Double-A was in store for 1959, with Hendley splitting time between Austin (Texas League) and Atlanta (Southern Association). Oddly, he performed better in Texas (11-9, 2.95 ERA in 146 1/3 innings, helping the team to the championship in the post-season playoffs) than at home in Georgia (4-6, 5.02 ERA, 61 innings).

The organization felt he was ready to take the next step in 1960 with the Triple-A Louisville affiliate. There Hendley reached his professional zenith in victories (16) and strikeouts (147), helping his team to the Junior World Series crown. His poise was impressive; he was more than six years younger than the league average but he completed 12 games while allowing only four longballs. The parent club needed fresh blood. Johnny Sain had retired in 1955 and Warren Spahn was nearing 40 years of age. Warranted optimism was in the air.

Milwaukee did not bring Hendley north when the 1961 spring training season ended but he was expected to join the team soon thereafter. An additional sprinkle of seasoning (six more games) with the Colonels was all it took for Hendley to graduate to the big leagues, but trouble lay ahead. In his first minor-league start of the season, he suffered the first of several elbow injuries that would zap his speed.

Nonetheless, he was quickly called into action against the Chicago Cubs on June 23, tossing 7 1/3 frames and allowing 10 hits and four runs in his first big league start, a 5-3 loss at Milwaukee County Stadium. Future Hall of Famer and teammate Ron Santo connected for a single in the first inning after Hendley retired the first two men. A strikeout of George Altman closed the inning and likely calmed whatever nerves the young southpaw may have been experiencing. He registered his first victory five days later in St. Louis, limiting the Cardinals to three runs in another 7 1/3 innings, as the Braves won 8-3. For the season, he won five games against seven losses, alternating between the starting rotation and the bullpen. He was the starter in 13 of his 19 appearances. He had two complete game wins (July 20 against Philadelphia and August 31 against the Dodgers) limiting his opponents to one run apiece. He lost another full-length effort against the Giants on September 18. Hendley took a 2-1 lead into the ninth inning, but Felipe Alou led off with a single and Orlando Cepeda hit a 2-run walk-off home run to give the Giants a 3-2 victory.

Hendley’s solid rookie season earned him the third spot in the 1962 rotation behind the ageless Spahn and the reliable Bob Shaw. He gave the team exactly 200 innings across 29 starts and six relief appearances, earning his first save (April 18 vs. San Francisco) and shutout (July 1 vs. Chicago). His 1963 season had a rough start. He entered in relief on Opening Day and, after retiring five straight batters, yielded three straight singles and absorbed the loss against Pittsburgh. But he manhandled the hapless New York Mets on April 14, tossing a 10-inning, four-hit 1-0 shutout. When the year ended, his personal ledger was 9-9 with 169 1/3 innings pitched for yet another middling Braves club. In his first three seasons, the Braves finished fourth (83-71), fifth (86-76), and sixth (84-78).

Perhaps swayed by the traditional pitching barometer of wins and losses, Milwaukee sought to shake up its pitching staff, striking a deal with San Francisco. The Giants shipped their future manager, Felipe Alou, and three other players for Hendley, Shaw, and Del Crandall during the 1963 winter meetings. Then-skipper Alvin Dark was enthusiastic, noting, “We gave up a good ball player (Alou) to get two pitchers. Hendley and Shaw are the heart of the deal.”2 While the team won in 17 of his 30 appearances, Hendley finished the season at 10-11. All but two of his 11 losses were by fewer than two runs, a tough reminder of the capricious nature of Lady Luck. The Giants started hot (15-5 in their first 20 games). A May 9 contest against the Dodgers was memorable. Hendley went the distance, striking out a dozen opponents and allowing only two runs. Sandy Koufax took the loss, yielding three runs in six innings and dropping his record to 2-3. Over the balance of the season, Koufax went 17-2.

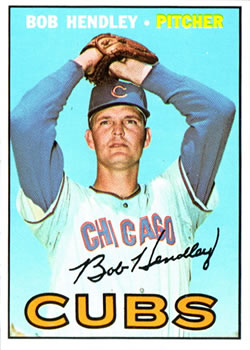

Hendley’s time with San Francisco was short-lived. Early in 1965, the club swapped his contract, plus those of Ed Bailey and Harvey Kuenn, for Dick Bertell and Len Gabrielson of the Cubs.3 Hendley pitched sporadically, mostly in relief, not seeing action from May 8 to May 25. Still, his perspective was positive. “Maybe I’ll get a chance to pitch. That’s what I’m in this game for.”4 He was inconsistent, allowing three or more runs in five of his 12 appearances before being demoted to Triple-A Salt Lake City. His stint with the Bees afforded him the chance to pitch regularly, starting seven games with 47 strikeouts in 52 innings, posting a 2.96 ERA, and earning his ticket back to The Show. He pitched strongly on September 2, yielding three runs (two earned) in 7 1/3 innings to pick up the victory against the Cardinals.

Hendley’s next game, September 9, 1965 would be memorable — his best performance in the majors. Unfortunately, his opponent was better.5 By definition, perfect games are exceptionally rare occurrences. Everything must go flawlessly. No momentary lapses in concentration. No weather-related snafus. No blown calls. Such narrow room for error would rattle any pitcher, but Sandy Koufax was not just any pitcher. The Dodger ace had already tossed three no-hitters in his career and was familiar with the tightrope walk.

Hendley’s next game, September 9, 1965 would be memorable — his best performance in the majors. Unfortunately, his opponent was better.5 By definition, perfect games are exceptionally rare occurrences. Everything must go flawlessly. No momentary lapses in concentration. No weather-related snafus. No blown calls. Such narrow room for error would rattle any pitcher, but Sandy Koufax was not just any pitcher. The Dodger ace had already tossed three no-hitters in his career and was familiar with the tightrope walk.

The zeros were entrenched in the scoreboard by the fourth inning of the September 9 contest. In the fifth, a hard-fought walk by Lou Johnson yielded the game’s first baserunner. What came next is a textbook example of why statistics yield answers but not always foolproof strategy. Today’s much-derided sacrifice bunt, very much en vogue during the pitching-dominant 1960s, advanced Johnson to second base. Was Ron Fairly playing for one run, given how his teammate was performing on the mound? It’s hard to tell, but he confessed that, “Hendley did not throw the ball as hard as Sandy. It was probably one of the best games of his career. It was great pitching all night long.”6 According to Vin Scully, Hendley may have had a play at second on the bunt and initiated a double play that may have changed history. Johnson’s subsequent steal of third base — in a year where he would record 15 thefts — was as pivotal as it was dicey. For his career, he would be successful roughly two-thirds of the time (50-for-74). Cubs catcher Chris Krug, part of a triumvirate with Vic Roznovsky and Ed Bailey, threw wildly to third and an unearned run scored. Fifty years later, Hendley was adamant that the blame rested on his shoulders. “People talk about Chris Krug throwing the ball into left field, but it was nobody’s fault. I’m the guy who let Lou Johnson get too big a lead.”7

We know the winner of a perfect game must be stellar, but the number of perfect games that have ended with a 1-0 score is striking. In spite of opposing perfection, the loser fails only by the slimmest of margins. Analysis of all 213,370 regular season games between 1871 and 2016 reveal only 4,800 (2.25%) ended in a 1-0 score.8 And yet, of the 23 official perfect games as of 2020, seven (30%) ended that way.9 Koufax’s, the eighth, was then the third of this variety.10

Ed Walsh (1908 versus Addie Joss), Jim McCormick (1880 versus Lee Richmond), and Tim Belcher (1988 versus Tom Browning) were all on the losing side of perfect games in which they did not allow an earned run. Hendley’s luck was worse, however — he yielded only one hit (a seventh-inning double by Johnson) which played no role in the scoring.11 The game continues to hold the record for fewest hits by both teams.

Reflecting afterward, a gracious Hendley said, “I not only got beat by one of the all-time great pitchers, but I got beat by class. I never met a finer gentleman than Sandy Koufax.”12 For his part, Koufax returned the compliment. “Bob and I shared a very special night that night. There’s a possibility I may have enjoyed it just a little bit more than he did.”13 On another occasion, the Hall of Famer reflected, “I think it was a great game because Bob Hendley pitched a one-hitter. It looked like we were going to be there all night. Big thing it was a 1-0 game and we were fighting for the pennant.”14 SABR members in 1995 voted the contest as the “greatest game ever pitched.”15

Sequels are seldom as good as the originals. Perhaps the 6,220 patrons at Wrigley Field on September 14, 1965, thought they might not be privy to the kind of virtuoso performance seen just five days earlier across the country. The same cast of characters was assembled but against a different backdrop. As it developed, those in attendance were treated to another master class in pitching and resilience. Even so, the first chapter has been immortalized in baseball lore. The second one remains mired in comparative obscurity.

Bravado often prompts pitchers to say “just give me one run.” In this case, Hendley got two, but one run was the margin of victory. Billy Williams, one of the Cubs’ three Hall of Famers in the lineup September 14, 1965, homered off Koufax with Glenn Beckert aboard in the sixth. The next inning, pitcher Don Drysdale — a prolific pinch-hitter — was asked to bat for Koufax. With two men on base via Hendley walks, Drysdale’s RBI single cut the lead in half. Hendley got out of the inning and allowed just one runner the rest of the way. Maury Wills led off the eighth with a bunt single, but Hendley promptly picked off the base-stealing threat, preserving the 2-1 Cubs victory. The game lasted one hour and 57 minutes.

Post-game, Koufax reminded sportswriters about a pitcher’s mentality. “It’s not the pitcher I have to beat. It’s the team.”16 Many years later, Hendley was as gracious as an Oscar nominee losing to a more popular actor. “We pitched against each other twice in six days. We both gave up two runs, we both allowed five hits. We both retired early [Hendley at 28, Koufax at 30], we both had elbow problems. He was great, I was average.”17

Altogether, Koufax and Hendley started against each other four other times in their careers. Hendley also relieved his team’s starter in two other games begun by Koufax, August 8, 1961 and June 29, 1963. Neither Hendley nor Koufax were involved in either decision.18 Hendley won three of the other four matchups while Koufax only won once. Very few players enjoyed that kind of success against arguably the finest southpaw in history.19

The 1966 Cubs hit rock bottom, finishing tenth in the National League. Hendley was assigned a new task as a reliever. Of his 43 appearances, all but six came in relief. He was involved in nine decisions (four wins, five losses) and registered a club-leading seven saves (on a staff that included, at one time or another, 23 pitchers). The rest of his participation was inconsequential as he appeared with Chicago trailing its opponent. He nonetheless took the mound for whatever task was needed, with May 28 as a prime example. Hendley entered the game in the top of the eighth inning as the Braves led the Cubs 3-2. He allowed a home run to Denis Menke and an unearned run later in the inning that included plate appearances by future Hall of Famers Eddie Mathews and Hank Aaron. All signs pointed to yet another loss for the North Siders, but they scored three runs in the bottom half to tie the score. Manager Leo Durocher stuck with Hendley. It paid off. Hendley kept Atlanta scoreless for the next four innings before Santo swatted a two-out three-run homer for the win.

The New York Mets acquired Hendley on June 12, 1967 for Rob Gardner and a player to be named later (John Stephenson). Hendley had thrown 12 1/3 innings for the Cubs in the young season, “winning ugly.” His 6.57 ERA, thanks in part to four home runs allowed, was good for two wins and zero losses. He pitched better for the Mets, starting 13 games and going 3-3. His season-best performance was again against the Dodgers, this time beating Drysdale in a complete game effort on July 23.20 Although Hendley’s duels with Koufax are better remembered, he battled the Dodger right-hander almost as often. In their eight shared starts, Hendley compiled a 3-3 record while Drysdale, ever the workhorse, featured in every decision with four wins and four defeats.21 Drysdale also started a game in which Hendley appeared in relief.22

Hendley’s big-league career coda turned out to be against Chicago in a relief appearance on September 3, striking out fellow pitcher Bill Hands, who was on his way to a complete-game shutout. At age 28, Hendley was the average age of his fellow players for the first time in his career, but the Mets opted to demote him to Triple-A for the upcoming season. Over 1968 and 1969, he played in 54 games for Jacksonville and Tidewater of the International League, again shifting between the bullpen and the starting rotation. Jacksonville won the International League playoff in 1968, and Tidewater won the regular season championship in 1969, but Hendley’s desired return to the majors did not materialize.

After the 1968 season, Hendley optimistically endured his third elbow surgery. Indeed, Mets GM Johnny Murphy noted, “I have never talked to a pitcher who was as enthusiastic about an operation as Hendley. Bob says he has never been able to move his arm the past five years the way he can now.”23 As 1969 progressed, the pitcher delivered robust minor league performances, including consecutive complete games on April 30 and May 5. “This is the first time I’ve struck out 11 men in a long, long time, and it’s the first time I’ve pitched complete games back to back in quite a while,” he told The Sporting News.24 As the season progressed, however, the Amazin’ Mets captured the NL pennant and then the World Series without Hendley.

Hendley forged a big-league career record of 48-52 across seven seasons and four teams, with an additional 62-47 mark in the minors. He faced Maury Wills the most in the majors. The speedy shortstop terrorized him, hitting .356 with a .390 on-base percentage in 73 at-bats. Ernie Banks slugged 1.250 (four home runs, four doubles, and six singles) against Hendley. Collectively, Hall of Famers Stan Musial, Willie Mays, Duke Snider, and Roberto Clemente managed only 11 hits in 63 at-bats, a fact most players would boast about, but not the modest Hendley.

Following the 1969 season, Hendley retired from active competition and returned to his native Georgia. He had diligently prepared for a post-baseball career, attending Mercer University during the off-seasons to earn a bachelor’s degree. He also joined the Army Reserves, musing, “If baseball hadn’t been going good, I probably would’ve been a second lieutenant.”25

Hendley moved on to coaching a new generation of pitchers, with Tattnall Square Academy (1970-1974), River North Academy High School (1975-1982), and Stratford Academy (1993-1999). The latter’s baseball field was renamed in his honor, a fitting tribute to the Georgia Sports Hall of Fame inductee (Class of 2015).

The previous year, Hendley received another honor, alongside Koufax and Scully. The New York chapter of the BBWAA gave them the 2014 Willie, Mickey, and the Duke Award, which recognizes groups of people forever intrinsically tied in baseball history.26

Media-shy, Hendley politely declined to be interviewed for this biography. He still lives in Macon with his wife Runette (née Harris), close to their children, Bart and Brett, and their grandchildren. Prompted to reflect on his accolades in 2016, Hendley was modest. “I had a 12-year career in baseball that was rewarding and is still rewarding because of the pension plan. But my 30 years as a teacher and a coach, I feel, was more rewarding.”27

Last revised: January 21, 2021

Acknowledgements

- Bart Hendley for providing valuable details about his father, Bob Hendley.

- John C. Hill for connecting the author to Bart Hendley.

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Bruce Harris and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author relied extensively on Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, and the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball.

Notes

1 Gene Asher, “Sports Legends: When A One Hitter Wasn’t Enough,” Georgia Trend, June 30, 2012, https://www.georgiatrend.com/2012/06/30/sports-legends-when-a-one-hitter-wasnt-enough/.

2 Associated Press, “A ‘Perfect Trade,’” Ocala Star Banner, December 4, 1963: 12.

3 Associated Press, “Ed Bailey, Hendley, Kuenn Traded for Bertell, Gabe,” The Spokesman-Review (Spokane Washington), May 30, 1965: S2.

4 “Ed Bailey, Hendley, Kuenn Traded for Bertell, Gabe,” The Spokesman-Review.

5 https://sabr.org/gamesproj/game/september-9-1965-a-million-butterflies-and-one-perfect-game-for-sandy-koufax/.

6 Phillip Ramati, “Perfect Match: One Magical Night, Macon Native Bobby Hendley Countered One of Baseball’s Greats Pitch for Pitch,” The Telegraph (Macon, Georgia), February 19, 2015, macon.com/sports/article30174942.html.

7 Ramati.

8 public.tableau.com/views/MostCommonBaseballScores/Dashboard1?:embed=y&:display_count=yes&:showVizHome=no.

9 baseball-almanac.com/pitching/piperf.shtml.

10 baseball-almanac.com/pitching/piperf.shtml.

11 baseball-almanac.com/pitching/piperf.shtml.

12 Asher.

13 Steve Hummer, “Macon’s Bob Hendley Made History with Koufax,” The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, August 28, 2016, ajc.com/sports/baseball/macon-bob-hendley-made-history-with-koufax/x2LDaatWdg635SzS1yCPhP/.

14 George Castle, “Great Outing, Even Greater People in Sandy Koufax Perfecto Against Chicago Cubs,” Chicago Baseball Museum, September 3, 2015, chicagobaseballmuseum.org/wp-content/uploads/CBM-Sandy-Koufax-perfect-game-part-2-20150903.pdf.

15 SABR Bulletin, April 1995 (question) and July 1995 (results), sabr.box.com/shared/static/bvigzo50ux171xfv3o2b.pdf.

16 Associated Press, “Rub Sandy in Wound,” The Toledo Blade, September 15, 1965: 56.

17 Marty Noble, “The Day Hendley Allowed Just One Hit, Koufax Was Perfect,” MLB.com, September 9, 2015, mlb.com/news/bob-hendley-one-hitter-loses-to-sandy-koufax/c-148255150.

18 retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1961/B08080LAN1961.htm, retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1963/B06290LAN1963.htm.

19 Box scores for the six Koufax/Hendley shared starts: retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1962/B04150LAN1962.htm, .retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1963/B08150MLN1963.htm, retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1964/B05090SFN1964.htm, retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1965/B04300LAN1965.htm, retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1965/B09090LAN1965.htm, retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1965/B09140CHN1965.htm.

20 retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1967/B07230NYN1967.htm.

21 Box scores for the eight Drysdale/Hendley shared starts: retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1961/B08310MLN1961.htm, retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1962/B09190MLN1962.htm, retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1963/B07190MLN1963.htm, retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1963/B04220LAN1963.htm, retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1964/B09090SFN1964.htm, retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1964/B08260LAN1964.htm, retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1966/B06160LAN1966.htm, retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1967/B07230NYN1967.htm.

22 retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1965/B05080SFN1965.htm.

23 Jack Lang, “Grin and Bear It — Gil Sees Mets’ Movies,” The Sporting News, January 6, 1968:42-44.

24 Abe Goldblatt, “Vet Hendley’s Bags Packed; He’s Ready for Met Phone Call,” The Sporting News, May 31, 1969: 35.

25 Ramati.

26 baseball-almanac.com/awards/willie_mickey_and_the_duke_award.shtml.

27 Hummer.

Full Name

Charles Robert Hendley

Born

April 30, 1939 at Macon, GA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.