Dave Skaugstad

“He’s too young to throw a no-hitter!”1 With the words of Cincinnati Redlegs manager Birdie Tebbetts still ringing in his ears, 17-year-old southpaw Dave Skaugstad took the mound on September 29, 1957 at Milwaukee’s County Stadium. Appearing in his second major-league game, he relieved 20-year-old rookie Jay Hook, who’d held the National League pennant-winning Milwaukee Braves hitless through five innings. Skaugstad retired the first five batters he faced, including a trio of future Hall-of-Famers, before losing the no-hitter in the sixth.

“He’s too young to throw a no-hitter!”1 With the words of Cincinnati Redlegs manager Birdie Tebbetts still ringing in his ears, 17-year-old southpaw Dave Skaugstad took the mound on September 29, 1957 at Milwaukee’s County Stadium. Appearing in his second major-league game, he relieved 20-year-old rookie Jay Hook, who’d held the National League pennant-winning Milwaukee Braves hitless through five innings. Skaugstad retired the first five batters he faced, including a trio of future Hall-of-Famers, before losing the no-hitter in the sixth.

The first player born in the 1940s to appear in a major-league game,2 Skaugstad never played in another. Untamable wildness, unresolved injuries, and a commitment to serve his country kept him from making it back. Skaugstad’s professional career, limited to parts of six seasons, played out against a backdrop of some of the most pivotal events of the Civil Rights movement, and ended on the day of the first nationwide Vietnam anti-war protest. Once his playing days were over, Skaugstad devoted himself to solving serious crimes as a police detective in Southern California and sharing his unvarnished opinions on a few not-so-serious motion pictures.

David Wendell Skaugstad was born on January 10, 1940, in Algona, Iowa, a small town in north-central Iowa. He was the second of three children born to Earl and Lorna Skaugstad, residents of nearby Bode. Dave’s arrival in Kossuth County was a newsworthy event; both his birth and return home from Kossuth Hospital were reported in local newspapers.3 Earl, a basketball player, first baseman, and thespian in high school,4 was a trucker at the time of David’s birth.5

In the run-up to World War II, Earl took a job at John Deere’s Moline, Illinois plant, nearly 300 miles from home, leaving his family behind.6 The former plow factory had recently won new government contracts that grew to include the manufacture of ammunition, aircraft parts, mobile laundry units, as well as military tractors, armored trailers, and tank transmissions.7 Soon after Dave turned 4, Algona became the site of a German prisoner-of-war camp that held nearly 10,000 prisoners, many of whom worked on nearby farms.8 As the war wound down in the summer of 1945, Earl was inducted into the military and stationed at Camp Roberts, a massive training center in central California.9

Before the year’s end, Lorna moved with Dave and his older brother Jim to Compton, California, then a farming community south of downtown Los Angeles.10 Home to many Japanese-Americans interned during the war,11 Compton was in the midst of a population explosion when the Skaugstads arrived. The town’s population tripled in the 1940s, to nearly 48,000 residents by 1950. More people meant the need for more housing, which opened the door for Earl to go into the roofing business after he was discharged.12

Dave’s first recorded baseball exploits were as a pitcher for the Compton Optimists as a high school freshman, while Jim, a senior, did likewise for the Compton High School varsity.13 During Dave’s junior season in 1956, he starred on the mound for the Compton High Tarbabes and played halfback for the school’s football team.14 After the high school baseball season ended, Skaugstad played American Legion baseball, where he fanned 19 in a no-hitter.15

As a high school senior, Skaugstad began drawing significant attention from scouts and the press. At times erratic, fanning nine and walking 10 in one victory,16 he finished the season 5-1 and was selected as an All Coast League pitcher.17 After school, Skaugstad pitched batting practice for the Triple-A Los Angeles Angels at Wrigley Field, where he remembered getting to know Sandy Koufax, albeit briefly.18 Once again playing summer American Legion ball, he tossed another no-hitter and fanned 14 batters in an August tournament.19 Offers from major-league clubs started coming in for Dave, who featured a five-pitch arsenal.20

In 1957, the bonus rule dominated how major league teams acquired talent. Since the late 1940s major-league baseball had tried various rules tied to player bonuses to prevent wealthier clubs, like the New York Yankees, from hoarding ballplayers. Rule 3k, implemented in 1952 at the behest of Branch Rickey, required that any player signed for a bonus of $4,000 or more be immediately placed on the major-league roster of the club that signed him for a period of two years. Most clubs signed top prospects for bonuses above the threshold but having inexperienced “bonus babies” on a major-league roster often eroded team morale. Many older players resented such prospects for getting bonuses exceeding their own salaries and for taking roster spots from players better prepared to help teams win. Before long, clubs were skirting the bonus rule, offering youngsters illegal bonuses outside of their signed contracts.21

“I was courted by the Dodgers, Yankees, Red Sox, Phillies, and Reds,” Skaugstad told author Brent P. Kelley years later.22 The Yankees, he said, offered him a $50,000 bonus if he’d wait until the following year to sign, expecting the $4,000 bonus rule to be done away with for the 1958 season, which, in fact, it was. Skaugstad claimed the Red Sox offered him $35,000 over three years, with $6,000 a year “legitimate” and the rest “under the table.” “The Dodgers offered me $5,000 to pitch in one game with the . . . Los Angeles Angels.”23

On September 11, Skaugstad accepted an offer from the Cincinnati Redlegs,24 which included a major league contract for $2,750 a month.25 With less than a month left to the season, the contract amount ensured that Skaugstad’s compensation stayed below the bonus rule threshold.26 When asked by the Cincinnati Enquirer why he signed with Cincinnati, the 17-year-old stepped squarely in the bucket. “They offered me the best opportunity with the weakest pitching staff.”27 Imagine what the other Redlegs pitchers were thinking when Skaugstad first walked into the clubhouse. Skaugstad later admitted he planned to sign with the Dodgers, in anticipation of their move to Los Angeles. When Dodger management left the scout who’d been courting him out of initial contract negotiations, however, he felt betrayed and pivoted to the Redlegs.28 Skaugstad would be joining the big-league squad right away, but fully expected to be sent to the minors in 1958.29

The “teen-age mound whiz of the California high school circuit”30 was one of several fresh-faced youngsters to join the Redlegs in September 1957. Well out of the pennant race by then, Cincinnati management took the opportunity to get a look at several top prospects. Nineteen-year-old Curt Flood joined the team the same day that Skaugstad did, called up from Savannah (Georgia) of the Class-A Sally League, where he was learning to play third base.31 Also promoted that day was 18-year-old lefty Claude Osteen, who’d debuted with Cincinnati in July.32 Hook, signed in August for a bonus “in the neighborhood of $75,000,”33 saw his first major-league action in a mop-up role shortly before Skaugstad arrived in the Queen City.

Skaugstad made his major-league debut at Crosley Field on September 25, 1957, in a game featuring all four of the young Redlegs.34 Hook made his first major league start that night, against the last place Chicago Cubs. After allowing six hits and walking four in two-plus innings, he was removed for Osteen, in his first appearance since being recalled. After Osteen was pinch-hit for in the fifth, Skaugstad entered with the Redlegs trailing, 7-2.

The first batter that Skaugstad faced, Chuck Tanner, welcomed him with a single to right field. After inducing a flyout from Ernie Banks, Skaugstad walked Dale Long. A wild pitch to Walt Moryn moved the runners up to second and third. Skaugstad held fast, fanning Moryn and induced an inning-ending groundout from Bob Speake. He closed out the last three innings without allowing a run, scattering two walks and a pair of singles, while striking out a batter in each inning. In the bottom of the ninth, Jerry Lynch batted for Skaugstad and delivered the Redlegs’ 12th pinch-hit homer of the season, a new National League record.35 Flood followed with the first major-league home run of his career, cutting the Redlegs deficit in half. The Cubs went to their bullpen after that and held on for the win.

The day of Dave Skaugstad’s major-league debut was marked by a watershed event in the American Civil Rights movement. Escorted by Army paratroopers armed with fixed bayonets, nine Black students walked past an angry mob and entered Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas for their first full day of classes.36 The first Blacks to attend the previously all-White school, the Little Rock Nine triumphed in the first major test of the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark Brown vs. Board of Education ruling that declared unconstitutional any state laws establishing separate schools for Black and White students.37 Events in Little Rock likely grabbed the attention of many in the Redlegs locker room, especially Frank Robinson, the reigning Rookie of the Year and already a two-time All-Star, who’d endured intense bigotry on his path to the major leagues.38

Skaugstad’s second and final major-league appearance came in the last game of the Redlegs’ 1957 season. Manager Tebbetts tabbed Hook to make his second career start, against the Milwaukee Braves, in front of 45,000 fans at Milwaukee County Stadium. Looking to stay sharp for their upcoming World Series clash with the New York Yankees, Braves manager Fred Haney used his regular lineup. Hook dueled Bob Buhl to a scoreless tie through five innings, allowing the potent Milwaukee lineup two walks and no hits.

After the Redlegs failed to score in the top of the sixth, Tebbetts grumbled that Hook was too green to toss a no-hitter and sent out Skaugstad.39 The rookie retired the side in order, but ran into trouble in the seventh. After inducing groundouts from sluggers Eddie Mathews and Hank Aaron, he walked Wes Covington, then lost the no-hitter on a double by Joe Adcock. Rattled, Skaugstad walked pinch-hitter Nippy Jones to load the bases, then light-hitting catcher Del Rice to force in the first run of the game. Tebbetts pulled Skaugstad and brought in fireman Hersh Freeman.40

Skaugstad left to a cascade of boos from the over-capacity crowd.41 “It was a bit overwhelming to say the least,” he would recall many years later.42 43After the game he rode to Chicago with Manager Tebbetts, who informed him that, had he kept Milwaukee hitless, it would have been the first combined no-hitter by a pair of rookies. “Well, then I was really pissed at myself. It’d never entered my mind when I was out there on the mound.”44

Despite losing the no-hitter, the Cincinnati Enquirer said Skaugstad “displayed all the poise of a veteran.”45 A few weeks later, Redlegs beat reporter Earl Lawson passed along Tebbetts’ prediction of “fine careers” for Skaugstad and Osteen. “I was amazed at their poise,” marveled Tebbetts.46 Skaugstad finished the season with a 1.59 ERA in 5⅔ innings pitched, with a walk and a strikeout in two plate appearances.

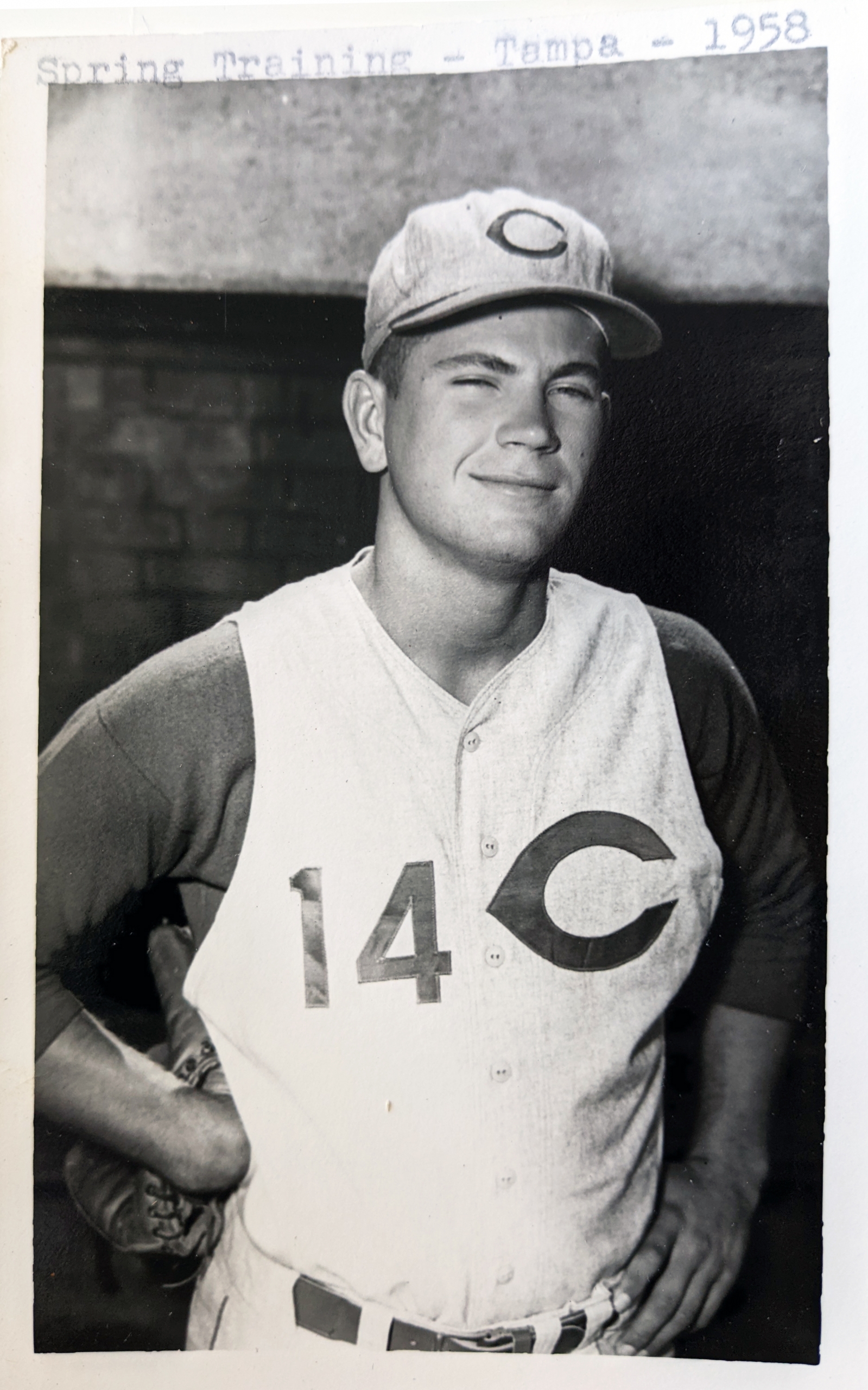

Following the 1957 season, Skaugstad pitched for Cincinnati’s team in the Southern California Winter League, shutting out the Los Angeles Dodgers squad in one game with 14 strikeouts.47 During rookie camp, Skaugstad wore that same number (14),48 and along with fellow portsiders Mike Cuellar and Jim O’Toole (a $50,000 bonus baby yet to make his professional debut) 49 was listed as a youngster capable of helping the Redlegs left-handed pitching situation “take a sharp turn for the better.”50 Hal Schumacher, a former New York Giants 20-game winner and partner in the Adirondack Bat Company, took a shine to Skaugstad’s bat as well as his live arm during the preseason. “This boy looks like a real good hitter… [On the mound,] he’s loose and can really throw that ball. You know, you can teach a kid a lot, but nobody can teach him to throw hard, that’s a natural gift . . . this kid looks like he has all the makings.”51 After playing briefly for the Redlegs “B” team during spring training,52 Skaugstad was optioned to the Wenatchee (Washington) Chiefs of the Class-B Northern League for the start of the 1958 season.53

Before Skaugstad headed west, the Cincinnati Enquirer’s Lou Smith wrote that “you wouldn’t believe how wild a kid pitcher like David Skaugstad can be when he tries to throw at half speed.”54 Smith proved prophetic. Skaugstad walked 10 or more in each of his first four starts for Wenatchee,55 and watched a pair of Wenatchee catchers allow nine passed balls in his second start.56 After going 1-4, with a 10.93 ERA, a league-leading 67 walks (in only 41 innings), and a 0.5 strikeout/walk ratio,57 Skaugstad was demoted to Visalia of the Class-C California League. Playing closer to home (Visalia being about 250 miles from Compton) seemed like it might be the right salve for the raw 18-year-old.

Skaugstad didn’t fare much better with Visalia. Used as a starter and reliever in equal measure, he finished the season 2-7, with a 7.52 ERA, 83 walks in 79 innings, and a 0.6 strikeout/walk ratio. “I wasn’t an overwhelming success [with Visalia, but] as it turned out, I did have an injury.”58 During the offseason, Skaugstad had surgeries on his left elbow and on his back, the latter to remove an infected growth at the bottom of his left shoulder blade.59

Assigned to the Double-A Nashville Vols after the season,60 Skaugstad instead spent spring training with the Seattle Rainiers of the Triple-A Pacific Coast League,61 before finding himself back in Visalia when the 1959 season opened. Now 6’1” and 185 pounds,62 he had much better results than the previous year. Visalia player/manager Dave Bristol, only 25 years old at the season’s start, alternated Skaugstad between starting and closing roles for the first month, had him play first base and in the outfield for the next few weeks, then returned him to the rotation. A switch-hitter, Skaugstad held his own at the plate and in the field, clubbing four home runs and driving in 21, while fielding .980 at first base. He finished the year with an 8-9 record, a respectable 4.23 ERA, and fewer walks (128) than strikeouts (130), including 16 on the second anniversary of his last American Legion no-hitter.63

While attending 1960 spring training in Tampa, Florida, Skaugstad understood that the manager of the Reds’ new Columbia farm team in the Class-A Sally (South Atlantic) League wanted him.64 He was disheartened when he was optioned to the Topeka Reds of the lower Class-B Three-I League,65 but saw an opportunity to learn from manager Johnny Vander Meer, a Reds pitching legend. Representing the city whose Board of Education had lost to Brown, Skaugstad won his first start, thanks to a save from reliever, and future pinch-hitter extraordinaire, Vic Davalillo.66 After losing his next five decisions, Skaugstad was reassigned to the unaffiliated Salem Senators of the Class-B Northwest League. His luck was no better there. Once again, wildness was to blame as he racked up 25 walks in 21 innings, combined with a 7.29 ERA. After less than three weeks in the Cherry City, he was reassigned back to Topeka. Soon he landed on the disabled list for back problems.67 While waiting to get back on the field, Skaugstad earned some pocket money by doing play-by-play for a local radio station.68 A month later, Skaugstad was shipped to the Geneva Redlegs of the Class-D New York-Penn League; the third last-place team he’d been with that year.69

After a dismal first outing in which he allowed seven runs in the second inning, Skaugstad “proved he still has some of his former polish” in winning his next start.70 He followed that with the most impressive performance of his minor-league career; fanning 18 in a four-hit shutout over Elmira.71 Skaugstad lost his next four decisions, the last one despite 18-year-old teammate Art Shamsky driving in seven baserunners in the second game of a season-ending doubleheader, including teenagers Tony Perez and Pete Rose, each finishing their first year of professional baseball.72 It was the last professional ballgame Skaugstad played for several years.

Towards the end of the 1960 season, Skaugstad’s back problems had returned, and he decided to take off some time to figure out what the problem was. “In those days, the ‘big club’ wouldn’t spend a dime [to diagnose lingering health issues] on somebody who was playing in the minors.”73 After choosing to sit out the entire season, he enlisted in the Army. Stationed in Europe, Skaugstad played baseball with the V Corps Guardians, which he considered equivalent to a Double-A level team. His back troubles diminished with the help of the team’s trainer, an ex-boxer who’d sparred with Joe Louis. He went 20-8 over two seasons with the Guardians and was twice selected for the All-European Theater team.74 While in Europe, Skaugstad also developed a forkball, which he had “half-assed worked on before (ala Sandy Koufax).”75 In September 1962, while stationed in Frankfurt, Skaugstad married Constance Sue Davis of Austin, Texas in a ceremony held in Basel, Switzerland, followed by a honeymoon in Italy and the Austrian Alps.76

After serving his country for three years, David Skaugstad returned to the states, and to professional baseball, in the spring of 1964. Out of respect for either his military service, his new-found forkball, or both, the Reds assigned the then-24-year-old veteran to one of their higher-level farm teams, the Double-A Macon Peaches of the Southern League. In Skaugstad’s first game back, he relieved for an Osteen, but not the one he’d relieved in his Cincinnati debut seven years earlier.77 (Macon starter Darrell Osteen was unrelated to Claude.) In Skaugstad’s first start, on a scorching Sunday in May, he authored a one-hit shutout against the oxymoronically-named Columbus (Georgia) Confederate Yankees.78 He had a far shorter, and less rewarding outing on June 30, when he entered a tie game against the Birmingham (Alabama) Barons with two outs and two on in the bottom of ninth and saw his first pitch hit for a game-winning single.79 The day after the Peaches left the city whose police brutality had precipitated passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Act into law, ending legal segregation.80

During the 1964 season, Skaugstad significantly cut his walks per nine innings from previous seasons (5.4 versus 7.7 to 11.2), and made the most appearances of his career (45). Getting both starting and closing assignments, Skaugstad finished the season 4-6, with a 4.16 ERA. He also had the most strikeouts per nine innings of any qualifying Southern League pitcher (9.1).81

The last season of David Skaugstad’s career opened with promise and ended in misery. After another spring training in Tampa, Skaugstad began the season back in Double-A, with the Knoxville Smokies. A strong start to his season prompted manager John Davis to laud Skaugstad, along with fellow pitcher Tom Frondorf. “We’re striking them out now instead of walking ‘em. I figure both of these pitchers will have good years.”82 The Knoxville News-Sentinel claimed Skaugstad had “probably the best ‘fork-ball’ pitch in the Southern League.”83 Consistency throughout the first half (leading the league in strikeouts, top five in ERA, and a pair of double-digit strikeout performances84) earned him a July call-up for a Cincinnati exhibition game against the Chicago White Sox.85 He warmed up in the bullpen once, but never got into the game.86 Rotator cuff tightness that began in June87 bothered him after he returned to Knoxville and he had a “miserable” last half of the season.88 Skaugstad finished the season with a 5-10 record, but with the lowest season ERA of his minor-league career (3.74).89

Skaugstad had given himself two years to make it back to the major leagues. The time had come to “hang up the ‘ol jock strap.”90 He hired on as a deputy in the Orange County, Florida sheriff’s office, and declined the Reds offer of a minor-league contract for the 1966 season.91 That day was also the first of two in which large demonstrations were held in nearly 100 American cities to oppose U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War, events which attracted far more protestors and media attention than any previous protests against the war.92

After working in Florida for a year, Skaugstad moved back to Southern California, where he joined the Orange County, California sheriff’s department. In 1970, the Orange County chapter of the American Legion awarded a Medal of Valor to Skaugstad and a fellow deputy for “outstanding action in apprehending two robbery suspects after coming under fire during a lengthy pursuit . . . and yet avoiding any injury to bystanders by his exercise of considerable constraint by not returning fire until completely safe to nearby spectators.”93

Violators of common decency also drew fire from Skaugstad. He sued a local movie theatre for airing a profanity-laced trailer for a coming attraction.94 “For the first time in a long movie-going career, I heard the four-letter word which commences with the sixth letter of the alphabet,” the now-single Skaugstad told the Newport Beach City council in a letter of protest.95 In the end, he settled with MGM Studios and the theatre chain for attorney’s fees, court costs, and $2,000, which he donated to Newport Beach Hospital.96

In December 1972, Skaugstad married the former Mary Loretta Sullivan. As with his first bride, they tied the knot in a location renowned for its skiing: Stowe, Vermont.97 They divorced less than two years later.98

During the 1980s, David was a detective for the Buena Park, California police department. He tirelessly investigated rapes, murders, bank robberies, and at least one kidnapping hoax.99 In his spare time, he played on the police department’s softball team, which “won quite a few medals (some Gold)” in the California Police Olympics.”100 To the north, his brother Jim, a golf pro in Oregon, gained notoriety by winning $100,000 from the Oregon lottery.101

After retiring from his policing career, Dave Skaugstad relocated to Desert Hot Springs, California, making frequent visits to nearby Baja Mexico. In the 2000s, he had several letters-to-the-editor published in the Palm Springs Deseret Sun, opining once that the movie Bull Durham “doesn’t really depict what life in the minors is all about.”102 And he also took the time to correspond with one baseball enthusiast interested in how he felt while trying to hold onto a no-hitter against the likes of Eddie Mathews and Hank Aaron, with 45,000 screaming fans rooting against him.

Last revised: June 2, 2022

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Nowlin and Jake Bell and fact checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted MyHeritage.com, FamilySearch.com, Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org and Statscrew.com. The author also relied heavily on correspondence received from David Skaugstad between November 2004 and July 2005. Mr. Skaugstad also provided the photo used here.

Notes

1 When recounting this game in 1960 to a reporter from the Des Moines Tribune, Skaugstad claimed not to have heard Tebbetts’ remark. In a 2004 letter to the author, he recanted his previous claim, saying “With my own ears I heard Birdie Tebbets [sic] say [it].” Bill Bryson, “Gains ‘Revenge’ From Seminick,” Des Moines Tribune, April 28, 1960: 29; Letter to the author from David W. Skaugstad, November 29, 2004.

2 Larry DeFillipo, “Point Men,” National Pastime, 2005: 119.

3 Kossuth County’s population was under 27,000 according to the 1940 U.S. census. “Hospital News,” Algona (Iowa) Upper Des Moines, January 11, 1940: 4; Humboldt (Iowa) Republican, January 26, 1940: 6.

4 Earl’s exploits on both the diamond and as a cast member in the senior class production of The Orchid Limousine are described within the same column of a local Bode newspaper. “Bode Retains County Cage Title,” Humboldt Independent, February 12, 1935: 1; “Orange and Black Spotlights,” Bode (Iowa) Bugle, May 10, 1935: 4.

5 1940 U.S. census, Bode, Iowa, Humboldt County, Delana Township, April 2-3, 1940, S.D. no. 8, E.D. no. 46-7, Sheet 1A.

6 Humboldt Republican, April 11, 1941: 8.

7 “John Deere (Deere and Company) in World War Two,” July 1, 2019, David D. Jackson’s The American Automobile Industry in World War Two website, http://usautoindustryworldwartwo.com/johndeere.htm, accessed March 23, 2022.

8 “Welcome to Camp Algona!” Camp Algona POW Museum website, https://web.archive.org/web/20200225084110/http://www.pwcamp.algona.org/, accessed March 23, 2022.

9 At one time the world’s largest military training center, Camp Roberts held up to 45,000 troops in 1945. “Here and There,” Mason City (Iowa) Globe-Gazette, June 26, 1945: 10; “Camp Roberts Army Base in Monterey, CA,” Military Bases.com website, https://militarybases.com/california/camp-roberts/, accessed March 23, 2022.

10 The family grew the following summer with the birth of a third child, Karen. “Service Notes,” Humboldt Republican, November 9, 1945: 8; Humboldt Republican, August 23, 1946: 7.

11 Compton’s Japanese American residents were interned at various “relocation centers” following President Roosevelt’s issuance of Executive Order 9066, in February 1942. See for example, Shizue Seigel, In Good Conscience (San Mateo, California: AACP Inc., 2006), 107-109.

12 Julian Chrischilles, “Heard Along the Main Stem,” Kossuth County (Iowa) Advance, April 10, 1958: 40.

13 David was mistakenly identified as a high school sophomore in a story published in Iowa detailing the successes of the Skaugstad boys. “Win in California,” Humboldt Republican, June 18, 1954: 2.

14 “Colton Gains Baseball Final,” San Bernardino (California) County Sun, March 28, 1956: 26; “Former Algona Youth A Cincinnati Redleg,” Algona Upper Des Moines, January 21, 1958: 25.

15 “Former Algona Youth”

16 “Tarbabes Hold Poly to 3 Hits,” (Long Beach, California) Independent, April 6, 1957: 10.

17 “Former Algona Youth”

18 It may be that Skaugstad met Koufax in a later year. In his self-titled 1966 autobiography, Koufax implies that his first visit to Los Angeles was shortly before the start of the 1958 baseball season, when he attended a welcome dinner and motorcaded to the Los Angeles Coliseum before an exhibition game there against the San Francisco Giants. Letter to the author from David W. Skaugstad, December 21, 2004; Sandy Koufax with Ed Linn, Koufax (New York: Viking Press, 1966), p. 125-126; Bob Timmermann, “60+ years of L.A. Dodgers Opening Day,” May 28, 2018, Los Angeles Public Library website, https://www.lapl.org/collections-resources/blogs/lapl/60-years-la-dodgers-opening-day, accessed April 1, 2022.

19 “Compton Ace Twirls Legion No-Hitter,” Independent, August 29, 1957: 25.

20 Skaugstad later told Lou Smith of the Cincinnati Enquirer that “my best pitch is a fast ball. I also like to throw a changeup and I have a curve, forkball, and a slider.” Lou Smith, “Lawrence Faces Phillies, Robin Roberts Today,” Cincinnati Enquirer, September 14, 1957: 25.

21 Wynn Montgomery, “Georgia’s 1948 Phenoms and the Bonus Rule,” Baseball Research Journal (Summer 2010). https://sabr.org/journal/article/georgias-1948-phenoms-and-the-bonus-rule/#:~:text=In%201952%2C%20led%20by%20Branch,league%20roster%20for%20two%20years.

22 Brent P. Kelley, Baseball’s Biggest Blunder: The Bonus Rule of 1953-1957 (Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 1997), 156-157.

23 Kelley, 156.

24 “Redlegs Sign Compton Ace,” Los Angeles Times, September 12, 1957: 78.

25 Kelley, 156. See also “Grandson of Bode Couple Pitcher,” Kossuth County Advance, October 8, 1957: 11.

26 Skaugstad’s recollection was that he received $3,999 for his time with the Reds in 1957. Kelley, 156.

27 Smith, “Lawrence Faces Phillies”

28 The scout was Kenny Myers, who also signed future major leaguers Willie Davis and Jim Merritt. Kelley, 157.

29 Smith, “Lawrence Faces Phillies”

30 “Cincinnati Reds Get Teen-Age Mound Whiz,” Mansfield (Ohio) News-Journal, September 12, 1957: 35.

31 Flood played five games with the Redlegs the previous September. “Reds to Send Nuxhall Against Phillies Tonight,” Cincinnati Enquirer, September 13, 1957: 35; Terry Sloope, Curt Flood bio, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/curt-flood/

32 “Major Leagues Recall Players Off Farm Clubs,” Claremore (Oklahoma) Daily Progress, September 5, 1957: 4.

33 Bill Ford, “$75,000 Near Figure Paid Jay Hook, Report; Star at Northwestern,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 18, 1957: 55.

34 Skaugstad was the fifth graduate of Compton High School to play in the major leagues. High school teammate Bobby Henrich, a distant relative of Yankee star Tommy Henrich, debuted in May 1957. Bennie Daniels, a three-sport star at Compton HS who served in the military for two years during the Korean War, debuted the day before Skaugstad did, for the Pittsburgh Pirates. The most acclaimed Compton HS graduate to that point was future Hall of Famer Duke Snider.

35 Tom Swope, “Tom Swope Answers Your Questions,” Cincinnati Post, May 28, 1958: 33.

36 In the days leading up to the military escort, Arkansas governor Orval Faubus had used the Arkansas National Guard to prevent the black students from entering the school, claiming the action was for the students’ own protection. President Eisenhower ultimately sent 1,200 members of the U.S. Army’s 101st Airborne Division to Arkansas and placed them in charge of the 10,000 National Guardsmen on duty. “Bayonets Impose Peace,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 26, 1957: 1.

37 “Little Rock Nine,” updated January 20, 2022, History.com website, https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/central-high-school-integration, accessed March 27, 2022.

38 Maxwell Kates, Frank Robinson bio, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/frank-robinson/

39 The following season, Tebbetts shared that before the game had begun, he had planned to get Skaugstad into the game, regardless of the situation. George Leonard, “Kid Pitching Corps Backs Vet Vols’ Bid,” The Sporting News, May 7, 1958: 37.

40 Freeman led the Redlegs in saves during 1956 (17) and 1957 (7).

41 Official capacity for Milwaukee County Stadium was 43,340 from 1954 on. Letter from Skaugstad, November 2004; Letter from Skaugstad, December 2004; Milwaukee County Stadium, ballparksofbaseball.com website, https://www.ballparksofbaseball.com/ballparks/milwaukee-county-stadium/, accessed March 27, 2022.

42 Letter from Skaugstad, December 2004.

43 Letter from Skaugstad, November 2004.

44 Letter from Skaugstad, November 2004.

45 “Reds Wind Up Typically, Lose to Milwaukee, 4-3,” Cincinnati Enquirer, September 30, 1957: 41.

46 Earl Lawson, “Rabe Rates Reds’ Raves with Razor Sharp Hill Role,” The Sporting News, October 9, 1957: 27.

47 “Tigers Tighten Grip on Lead in California Winter League,” The Sporting News, January 8, 1958: 26.

48 From photograph provided to the author by David W. Skaugstad.

49 Cincinnati Enquirer, March 27, 1958: 38.

50 Lou Smith, “Young Red Lefties Impressive,” Cincinnati Enquirer, March 4, 1958: 31.

51 Ritter Collett, “Journal of Sports,” Dayton (Ohio) Journal Herald, March 28, 1958: 22.

52 San Francisco Chronicle, March 26, 1958: 22.

53 Clause Osteen was optioned to Wenatchee along with Skaugstad. Cincinnati Enquirer, March 27, 1958.

54 In the same story, Smith quoted Tebbetts’ retort that he’d “rather have a pitcher who can’t throw soft, than one who can’t throw hard.” Lou Smith, “Kelly, Nuxhall Scheduled to Hurl Grapefruit Opener,” Cincinnati Enquirer, March 6, 1958: 43.

55 “Braves Win Opener, 13-9,” Tri–City (Washington) Herald, April 25, 1958: 11; “Solons in 13-12 Nod Over Chiefs,” Salem (Oregon) Statesman Journal, April 30, 1958: 9; “T-C Braves, Chiefs Score NW Victories,” (Salem, Oregon) Capital Journal, May 7, 1958: 21; “Lewiston’s Broncs Increase Margin,” Spokane Spokesman Review, May 15, 1958: 21.

56 “Solons in 13-12 Nod Over Chiefs”

57 In Skaugstad’s final appearance, Tri-City hurler Joe Drotar no-hit Wenatchee. “Drotar Flings No-No Game,” Salem Statesman Journal, June 15, 1958: 30; “Northwest Statistics,” Eugene (Oregon) Guard, June 22, 1958: 14.

58 Letter from Skaugstad, November 2004; Raymond Johnson, “Helms, Long Ball Hitter, Appears Top Addition,” Nashville Tennessean, December 4, 1958: 38.

59 Letter from Skaugstad, November 2004; Bill Bryson, “Gains ‘Revenge’ From Seminick,” Des Moines Tribune, April 28, 1960: 29.

60 “Vols Get Bonus Outfielder Bernie Parrish from Reds,” Nashville Banner, December 4, 1958: 48.

61 Letter from Skaugstad, November 2004.

62 “31 Volunteers with a Mission in ’59,” Nashville Tennessean, January 25, 1959: 45.

63 Exactly four years later, on August 28, 1963, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered his immortal I Have a Dream speech from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington D.C. “Port Hurler Blanks Redlegs,” Tulare (California) Advance-Register, August 29, 1959: 4.

64 Letter from Skaugstad, November 2004.

65 Letter from Skaugstad, November 2004.

66 In 1970, Davalillo delivered 23 pinch hits, one shy of Dave Philley’s then single-season record of 24. As a major-league pitcher, Davalillo was far less successful. Appearing in only two games, also during the 1970 season, he allowed one earned run without retiring a batter, for an ERA of infinity. Bill Bryson, “Topeka Hands Demons 4th Setback, 6-3,” Des Moines Register, April 28, 1960: 15; Rory Costello, Vic Davalillo bio, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/vic-davalillo/

67 Letter from Skaugstad, November 2004.

68 Letter from Skaugstad, November 2004.

69 Topeka was 64-74 at year end, tied for last place in the Three-I League, Salem was 14-33 and in last place after Skaugstad’s last game for them, and Geneva finished their season in last place, with a 54-75 record. Bob Robinson, “Jordan Answers Charges,” Capital Journal, June 13, 1960: 29.

70 “Auburn and Geneva Get Win in NY-P Contests,” Wellsville (New York) Daily Reporter, July 19, 1960: 6; “Geneva Posts 3-1 Win,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, July 23, 1960: 5.

71 Skaugstad also struck out the side in order in the fourth, fifth, and sixth innings. His performance ended his “personal mission” to be converted into a position player. “Pioneers Are Beaten, 3-0; Eighteen Fan,” Sayre (Pennsylvania) Evening Times, July 27, 1960: 16; “Geneva Lefty Whiff Artist,” Ithaca (New York) Journal, July 27, 1960: 18; Letter from Skaugstad, November 2004.

72 In the first game of the doubleheader, Wellsville’s Dick Sherrow no-hit Perez, Rose, Shamsky, and the rest of the Geneva lineup. Frank Cady,” Sherrow No-Hits Geneva as Braves Capture Pair,” Wellsville Daily Reporter, September 3, 1960: 5.

73 Letter from Skaugstad, November 2004.

74 “Pitching Appears Better as Grays Prepare for 1964,” Newport News (Virginia) Daily Press, March 8, 1964: 36.

75 Letter from Skaugstad, November 2004.

76 Mrs. Walter Thompson, “Bode,” Humboldt Independent, October 6, 1962: 4.

77 “Charlotte Game Postponed,” Charlotte Observer, April 27, 1964: 25.

78 Skaugstad recalled the temperature in Columbus that day was 98 degrees. He drove in three of the Peaches’ five runs in the game and carried a no-hitter into the eighth inning. Not in the lineup for Columbus was their 20-year-old outfielder, Compton native Roy White, 16 months away from his debut with the New York Yankees. “Barons Top Asheville by 10 to 6,” Anniston (Alabama) Star, May 18, 1964: 7; Letter from Skaugstad, November 2004.

79 “Barons Almost in Host Role,” Charlotte News, July 1, 1964: 14.

80 On May 3, 1963, Birmingham police, at the direction of Public Safety Commissioner Eugene “Bull” Connor, turned high-pressure fire hoses and German Shepherds on scores of young Black protesters in the downtown business area. Images of those brutal acts galvanized support in the U.S. Senate for passage of a civil rights bill. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., in a 1965 address to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, stated that events in Birmingham inspired the Civil Rights Act of 1964. “Selma to Montgomery March,” Stanford University’s Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute website, https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/encyclopedia/selma-montgomery-march#:~:text=In%20his%20annual%20address%20to,King%2C%2011%20August%201965), accessed April 1, 2022.

81 Baseball-Reference lists Skaugstad as fanning 9.08 per nine innings, while the Charlotte Observer reported 9.17. The author has reported the former value, rounded to the nearest tenth. Wilton Garrison, “And Who Else?…Should be Deac,” Charlotte Observer, November 11, 1964: 34.

82 “Smokies Shake ‘AA’ Slump, Tumble Chattanooga, 6-3,” Knoxville News-Sentinel, April 10, 1965: 8.

83 “Smokies Shuffle for Right Combo,” Knoxville News-Sentinel, June 23, 1965: C7.

84 Skaugstad tossed a masterful 12-strikeout, two-hit shutout against Montgomery in late May and fanned 11 in another victory over Montgomery in late June. Letter from Skaugstad, November 2004; Max Moseley, “Rebs Lose Doubleheader, End Smokies Series Today,” Montgomery Advertiser, May 30, 1965: 17; Harold Harris, “Smoky ‘Extras’ Bring 2-1 Victory,” Knoxville News-Sentinel, June 26, 1965: 7.

85 Harold Harris, “Go Getter White on ‘Center’ Stage,” Knoxville News-Sentinel, July 8, 1965: 33.

86 Letter from Skaugstad, November 2004.

87 Harold Harris, “Davis Calls Meeting of Slipping Smokies,” Knoxville News-Sentinel, June 24, 1965: 34.

88 Letter from Skaugstad, November 2004.

89 In his last professional game, Skaugstad lost to another former California high school star, Bill Landis. Landis had followed in Skaugstad’s footsteps, playing for Visalia in 1961, and would do so again by serving his country in the Army. In 1967, then a rookie with the Boston Red Sox, Landis left for six months of Army Reserve duty just days before his teammates won the American League pennant. Bill Nowlin, Bill Landis bio, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/bill-landis/

90 Letter from Skaugstad, November 2004.

91 “2 Smoky Pitchers to Sit Out Season,” Knoxville News-Sentinel, March 26, 1966: 5.

92 Protest parades on March 25 took place in New York City, Chicago, San Francisco, and Detroit, with smaller demonstration nationwide, such as one on the campus of the State University of New York at Stony Brook (the author’s alma mater). “Growing Antiwar Protests in the United States,” “Peace Walks Hit Stride,” Newsday (Melville, New York), March 26, 1966: 2; Vietnam War Commemoration website, https://www.vietnamwar50th.com/1966-1967_taking_the_offensive/Growing-Antiwar-Protests-in-the-United-States/, accessed April 10, 2022.

93 After a 100-mile pursuit by Skaugstad and another deputy, five shots from a 12-gauge shotgun brought the suspects’ car to a halt. “Deputies Who Held Their Fire Honored,” Los Angeles Times, May 15, 1970: 53; “Former resident received Medal of Valor,” Humboldt Republican, June 3, 1970: 10.

94 Vernon Scott, “Going to a G-rated movie with the kids? Watch out for that preview!” Independent, September 16, 1972: 27.

95 “Movie’s 4-Letter Word Spurs $2 Million Suit,” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 22, 1970: 10.

96 Scott, “Going to a G-rated movie”

97 Stowe is widely referred to as the Ski Capital of the East. Certificate of Marriage, David Wendell Skaugstad and Mary Loretta Sullivan, issued December 19, 1972, Stowe, Lamoille County, Vermont.

98 California Divorce Index, 1966-1984,” Mary L. Sullivan and David W. Skaugstad, July 1974, Orange, California, Department of Health Services, Sacramento.

99 Beverly J. Moore, “Suspect Admits Disneyland Extortion Try,” Los Angeles Times, March 11, 1982: 67; “Reward Offered for Clues to Buena Park Killer’s Identify,” Los Angeles Times, January 10, 1984: 38; “Police Say Strangulation Caused Woman’s Death,” Los Angeles Times, January 13, 1988: 62; Nancy Wride, “Bank Robbers Terrorize Teller’s Family Before Stealing $80,000,” Los Angeles Times, August 30, 1988: 62; “Kidnap hoax may mean prosecution,” Roseville (California) Press-Tribune, December 10, 1984: 7.

100 Letter to the author, with accompanying photograph, from David W. Skaugstad, July 13, 2005.

101 Jim and his wife Terry learned they were winners while hosting a watch party for a 1986 NBA playoff game. “Who cares who won?” (Portland) Oregonian, June 6, 1986: 41.

102 David W. Skaugstad, “Big deal,” Palm Springs Desert Sun, May 9, 2003: 27.

Full Name

David Wendell Skaugstad

Born

January 10, 1940 at Algona, IA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.