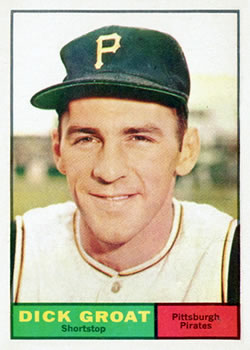

Dick Groat

Before Bo Jackson and Deion Sanders made “two-sport athletes” a vogue term in the 1980s and ’90s, there was Dick Groat. Groat lacked the power of Jackson or the speed of Sanders. But what he lacked in physical gifts he more than made up in guile and spirit. His collegiate career at Duke University earned him All-American honors in basketball and election to the College Basketball Hall of Fame. His baseball career saw him rise from the college ranks directly to the major-league level. He did not play an inning of a minor-league game.

Before Bo Jackson and Deion Sanders made “two-sport athletes” a vogue term in the 1980s and ’90s, there was Dick Groat. Groat lacked the power of Jackson or the speed of Sanders. But what he lacked in physical gifts he more than made up in guile and spirit. His collegiate career at Duke University earned him All-American honors in basketball and election to the College Basketball Hall of Fame. His baseball career saw him rise from the college ranks directly to the major-league level. He did not play an inning of a minor-league game.

At 5-feet-11 with a modest build, Groat may not have looked the part of a professional athlete. But he excelled under the guidance of two giants of their profession. At Duke, Groat was coached briefly by Red Auerbach, who went on to a career as coach and then general manager of the Boston Celtics that earned him election to the Basketball Hall of Fame. Later he was signed by Branch Rickey, a Hall of Famer as a baseball executive, to join the Pittsburgh Pirates. These two larger-than-life personalities helped shape Groat into the athlete and person he became: Auerbach taught Groat how to attain a competitive edge in competition, and Rickey instilled a mental discipline and fortitude in him.

Richard Morrow Groat was born on November 4, 1930, in Wilkinsburg, Pennsylvania, which is adjacent to Pittsburgh. He was the fifth and youngest child (after Martin, Charles, Elsie, and Margaret) of Martin and Gracie Groat. Martin Groat worked in the real-estate investment business.

At Swissvale High School Groat earned letters in basketball, baseball, and volleyball. He attended Duke University on a basketball scholarship. He became a two-time All-American in both basketball and baseball. On the hardwood, Groat was named the National Player of the Year after his senior season (1951-1952), when he averaged 26 points and 7.6 assists per game. He is the only player in NCAA history to lead the nation in both scoring and assists in a season. On May 1, 1952, he was the first player at Duke to have his uniform number (10) retired.

In baseball Groat played shortstop and helped to lead the Blue Devils to a 31-7 record and their first College World Series appearance in his senior year, 1952. He hit .370 and led the team in doubles, hits, runs batted in, and stolen bases. He was a two-time winner of the McKelvin Award, given to the Athlete of the Year in the Southern Conference.

In the summer of 1951, between Groat’s junior and senior years, Branch Rickey, general manager of the Pirates, invited Groat and his father to stop in his office. “We got there in the afternoon and Mr. Rickey pulled out a document and said: ‘If you sign this contract, you can play shortstop against the Phillies tonight,’ ” Groat recalled. After Groat pointed out that he still had another year of college, Rickey suggested that he could complete his education during the offseason. “Mr. Rickey, I’m down at Duke on a basketball scholarship,” Groat said. “I feel obligated to play the full four years. But I will tell you this much – if you make the same offer to me next June, I’ll sign.”1 (That was in the days before the free-agent draft.)

True to his word, Groat signed with the Pirates the next year, in June 1952, after Duke had been eliminated from the College World Series. His contract included a bonus said to be in the $35,000 to $40,000 range. Bypassing the minor leagues, he joined the Pirates in New York, where they were playing the Giants. His first day in uniform, June 17, Groat observed the action from the visiting team dugout at the Polo Grounds. The next day he made his major-league debut, pinch-hitting and grounding out to Giants hurler Jim Hearn. Groat got his first two hits the next day, stayed in the lineup for the rest of the season and led the team in hitting with a .284 batting average. Only two other regulars ended the season with a batting average above .270, catcher Joe Garagiola (.273) and first baseman-outfielder George Metkovich (.271). Under manager Billy Meyer, Pittsburgh finished the 1952 campaign in last place with a 42-112 record, 54½ games behind first-place Brooklyn.

Groat was helped during his rookie season by Pirate Hall of Famer Paul Waner, who operated some batting cages in nearby Harmarville. Groat would visit the batting cages before heading to Forbes Field each morning for practice. “He was fun to be with, I really liked Paul Waner,” Groat said. “He couldn’t have been nicer to me in every way. He helped me build confidence. … He was very patient, very understanding, and had a great hitting philosophy. Even at that age (49), he could still hit that machine and hit that ball hard.” 2

After the season Groat returned to Duke to finish his degree. He was drafted by the Fort Wayne Pistons in the first round (third pick overall) of the NBA’s college draft. (Groat always favored basketball, feeling that was the sport he excelled at the most.) “I never practiced with them,” Groat said of the Pistons. “I was still trying to get those credits from Duke, and the Pistons would fly me from school to games in a private plane. I loved pro basketball. Basketball was always my first love, mainly because I played it best and it came easiest to me.” 3 In 26 games with the Pistons, he averaged 11.9 points per game.

His basketball season was cut short when he was drafted again, this time by the US Army. For the next two years he fulfilled his military commitment at Fort Belvoir in Virginia. While serving in the military, he kept in shape playing basketball and baseball on the Belvoir Engineer teams.

Although the Pirates floundered during the Rickey era, the general manager was laying the groundwork for future success. In addition to signing Groat, Rickey also selected Roberto Clemente from Brooklyn via the Rule 5 Draft in 1954 and signed Bill Mazeroski the same year. Clemente and Mazeroski were key ingredients in bringing two world championships to Pittsburgh, and both are in the Baseball Hall of Fame.

A move Rickey made before Groat got to Pittsburgh benefited the player. He brought George Sisler to Pittsburgh in 1951. Sisler, who had worked for Rickey in Brooklyn, was the Pirates’ scouting supervisor and unofficial hitting coach. “Sisler teaches us to be ready for the fastball and adjust our swing for the curve,” Groat said at the time. “If you’re looking for a curve and get a fastball, you never hit it. But you can cut down on the speed of your swing to hit the curve.” 4

When Groat returned from military duty in 1955, he wanted to play both baseball and basketball. “Basketball was fun to me, and baseball was work,” he said. The Pistons offered a higher salary and would allow him to leave the team early for spring training. Groat cited the example of Gene Conley, who pitched for the Milwaukee Braves, and played basketball for the Boston Celtics. “Don’t bring up Conley with me,” Rickey told Groat. “As a starting pitcher he only works every fourth or fifth day, and he’s only a backup center in basketball. You are a regular player in both baseball and basketball. I think you should realize that eventually you won’t justify your salary in either sport.” 5 Persuaded by Rickey’s logic, Groat chose to focus on baseball.

Groat started slowly in 1955, hitting .229 in April and .235 in May. A slow start might have been expected, but Rickey would cut him no slack. Groat recalled talking to himself in the batting cages when he heard Rickey say just loud enough to be heard, “There is no way that the boy can improve. He never was an All-American in baseball and basketball.” 6 This may have been Rickey’s way of getting him to concentrate more at the plate. Groat ended the year hitting .267 for the last-place Pirates, who finished 38½ games out of first place under manager Fred Haney. He capped off the year by marrying Barbara Womble, once a top New York model, on November 11. They eventually had three daughters, Tracey, Carol Ann, and Allison.

Before the 1956 season, Rickey was replaced as general manager by Joe L. Brown. Brown did not share Rickey’s high opinion of Sisler, and dropped him as one of his first moves. He brought in Bobby Bragan to replace Haney. The change made little difference: The Pirates rose to seventh place but were still a distant 27 games behind pennant-winner Brooklyn. When Bragan began 1957 with a record of 36-67, he was fired and replaced by third-base coach Danny Murtaugh.

Groat began to flourish under Bragan, and then Murtaugh. His batting average leaped from .273 in 1956 to .315 in 1957 and .300 in 1958. The Pirates went from a last-place finish in 1957 to second place in 1958, with a record of 84-70, eight games behind Milwaukee. Both Groat and the Pirates regressed in 1959. He still hit well, batting .275, but he led the league with 29 errors at shortstop as the Pirates ended the season in fourth place. Groat appeared in the 1959 All-Star Game, the first of five appearances in his career.

One knock against Groat was that he could not hit with power. He did not strike out much, fanning more than 60 times in only one season. But as a contact hitter he was adept at hitting the ball through the open hole in the infield. Murtaugh allowed Groat to pick his spots to hit and run, often with Groat flashing a sign to the baserunner. Critics also pointed to his lack of range at shortstop and weak arm. Fellow shortstop Alvin Dark defended him. “They say he doesn’t have much range at shortstop. What’s range but getting to the ball?” Dark said. “You watch Groat. He’s always in front of the ball. He’s smart and he knows the hitters and plays position as well as anyone I ever saw. Maybe he doesn’t have a great arm, but he makes up for it by getting the ball away quicker than anyone else.” 7

Pittsburgh put it all together in 1960, winning the pennant by seven games over the Milwaukee Braves and then capturing the team’s first world championship since 1925 by defeating the New York Yankees on Mazeroski’s dramatic walk-off home run. Groat led the league in hitting with a .325 batting average, finished third with 186 hits, and was named the National League’s Most Valuable Player by both The Sporting News and the Baseball Writers Association of America. He had his best day at the plate on May 13 in Milwaukee when he went 6-for-6 with three doubles. He earned MVP honors (though teammate Roberto Clemente felt he should have won the award) even though Groat was sidelined for most of September with a broken left wrist after being hit by Milwaukee pitcher Lew Burdette. Returning to the lineup just before the end of the season, Groat hit .214 in the World Series with two doubles and two RBIs.

Over the next two years, the Pirates slipped back to the middle of the pack. In 1962, Groat led the league’s shortstops with 38 errors. After the season rumors circulated that Groat, who turned 32 in the offseason, Dick would be traded.

Meanwhile, in St. Louis, August Busch, Jr. had lured Branch Rickey to work as a senior consultant to the Cardinals’ front office. Busch was dismayed at the Cardinals’ inability to win a championship since 1946. Cardinals general manager Bing Devine and Rickey clashed immediately. Their relationship was rocky at the beginning and got worse as the months went by. Devine had been working to acquire Groat from the Pirates, but Rickey quashed it. Rickey believed in trading older players, not acquiring them. He looked to dump players a year early, when there was some value, as opposed to a year too late.

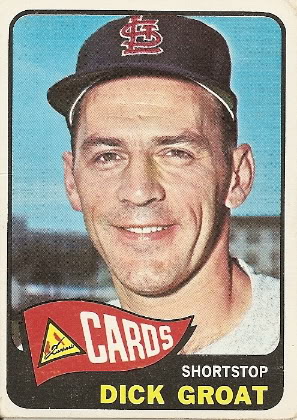

Cardinals skipper Johnny Keane also wanted Groat to join the team. “With Groat to assist and guide him, I believe Julian Javier would develop into a truly great second baseman,” Keane said. “Our infield also would be improved by the presence of a take-charge guy such as Groat. Our infield as constituted last season was not an aggressive combination.” 8 A deal was made on November 19, 1962, and Groat went to St. Louis with relief pitcher Diomedes Olivo in exchange for pitcher Don Cardwell and shortstop Julio Gotay.

After some initial apprehension, Groat was happy to be heading to St. Louis. “I think the Cardinals are a good club that got some tough breaks last season,” he said. “I know I am not young, and I’d like to play on a contender a few more years.” 9

The Cardinals started 1963 with a 14-6 record in April. They held a slim 1½-game lead over the Dodgers and Giants at the end of June. The infield quartet of first baseman Bill White, second baseman Julian Javier, third baseman Ken Boyer, and Groat were having very good years at the plate. At midseason White, Boyer, and Groat were hitting .300 or better and Javier was holding steady with a .270 batting average. All four infielders started for the National League in the All- Star Game.

The Cardinals started 1963 with a 14-6 record in April. They held a slim 1½-game lead over the Dodgers and Giants at the end of June. The infield quartet of first baseman Bill White, second baseman Julian Javier, third baseman Ken Boyer, and Groat were having very good years at the plate. At midseason White, Boyer, and Groat were hitting .300 or better and Javier was holding steady with a .270 batting average. All four infielders started for the National League in the All- Star Game.

Late in the season the Cardinals went on a torrid pace, winning 19 of 20 games from August 30 to September 15. On September 16 they trailed Los Angeles by one game, with the Dodgers coming to St. Louis for a three-game series. The Dodgers swept the series, including a four-hitter by Sandy Koufax in the second game and a 6-5 Dodgers victory in 13 innings in the finale. The Cardinals went on the road and dropped five games in the final week of the season, putting an end to their pennant hopes.

Groat ended the 1963 season with career highs in hits (201), doubles (43), triples (11), and RBIs (73). His .319 batting average tied for third and his 43 doubles led both leagues. He finished second to Koufax in voting for the MVP.

During the season center fielder Curt Flood said he learned a lot about positioning from the veteran shortstop. “I’ll play a hitter a certain way, and then I’ll notice that Dick is a bit further to the right than I would have thought. His knowledge of the hitters is so good, I figure he must be right, so I move to the right too,” Flood said. 10

The Cardinals finally broke through in 1964, capturing their first world championship since 1946. Groat hit .292, drove in 70 runs and stroked 35 doubles. In a thrilling race to the finish, St. Louis went 21-8 in September. The Philadelphia Phillies held a 6½-game lead over St. Louis and Cincinnati on September 20, but then closed out the month on a ten-game losing streak. When the Cardinals sewed up the pennant in the final game of the season, against the New York Mets, Groat hit two doubles and scored twice in the Cards 11-5 victory.

After going down two games to one in the World Series against the Yankees, the Cardinals won three out of four and were crowned world champions. Groat had only five hits for a.192 batting average, but also got on base four times with walks.

In Game Four, relief pitcher Roger Craig walked Mickey Mantle and Elston Howard with two outs in the third inning. The next batter was Tom Tresh. Groat knew that Craig had an excellent move to second base, and at times they ran what they called “the daylight play.” If Groat got inside the runner at second base and there was daylight between them, they would try for the pickoff. There was no signal to the play; Craig and Groat just did it. Groat was able to get between Mantle and the base. Craig turned and threw, and they picked Mantle off. Mantle headed back to the dugout, past Craig. “You son of a bitch,” Mantle said. “You show me up in front of forty million people.” 11

Manager Johnny Keane surprised everyone by resigning after the World Series and replacing Yogi Berra as manager of the Yankees. Cardinals coach Red Schoendienst took over for Keane. Groat was happy for the switch. “He understands ballplayers,” Groat said of Schoendienst. “Everything he does, he does for the good of the players. He’s considerate of their feelings at all times. That’s why I think he is going to do a tremendous job for us.” 12

Neither Groat nor the Cardinals enjoyed a successful season in 1965. The team slipped to seventh place in the ten-team league and the 34-year-old Groat hit .254. After the season the Cardinals traded Groat with first baseman Bill White and reserve catcher Bob Uecker to Philadelphia for pitcher Art Mahaffey, outfielder Alex Johnson and catcher Pat Corrales. “We got him because I know he can still hit. But, more important, he knows he can still hit,” said Phillies manager Gene Mauch. “And a player like Groat always hits better when his ballclub is in the game all the time.”13

Besides playing shortstop for the Phillies, Groat also played 20 games at third base, a position he disliked but nonetheless was willing to play. The team finished fourth, eight games behind the first-place Dodgers. On May 18, facing the Cardinals, Groat got his 2,000th career hit, a single to center field off Bob Gibson.

Groat was hobbled during the 1967 season by cellulitis, an inflammation of the tissues and veins in his right ankle. The ankle swelled to three times its normal size and Groat’s temperature rose to 104 degrees. He was hospitalized for two weeks and missed two months of the season. He played in only ten games for the Phillies before being sold to San Francisco on June 22. After batting a puny .156 for both teams, he retired after the season. Groat ended his playing career with a batting average of .286 in 14 major-league seasons.

For many years Groat had worked during the offseason as a salesman for Jessup Steel in Washington, Pennsylvania. In 1965 he took a new direction. Groat and former Pirates teammate Jerry Lynch built a public golf course, called Champion Lakes, in Laurel Valley, 50 miles east of Pittsburgh. As of 2011, Groat was still spending half his time living at Champion Lakes and keeping active in the day-to-day operations of the course. He also spent 40 years (1979-2019) as a color analyst on radio broadcasts of University of Pittsburgh basketball games. In 1990 Barbara Groat died of lung cancer. She and Dick had been married for 35 years.

In November 2007 Groat was inducted into the National Collegiate Basketball Hall of Fame in Kansas City, Missouri. He has also received the Arnold Palmer Spirit of Hope Award, given annually to people who serve as an inspiration to children all over the world. He remained active with charity events involving the Pittsburgh Pirates Alumni Association.

Postscript

Groat died at the age of 92 on April 27, 2023.

Sources

http://minors.sabrwebs.com/cgi-bin/index.php

http://pittsburghpanthers.cstv.com/sports/m-baskbl/pitt-m-baskbl-body.html

http://pittsburgh.pirates.mlb.com/index.jsp?c_id=pit

http://www.collegebasketballexperience.com/inductees.aspx?alpha=all

http://www.pittsburghpanthers.com/genrel/111907aad.html

http://www.basketball-reference.com/players/g/groatdi01.html

Notes

1 The Sporting News, April 2, 1966, 7

2 Jeremy Anders. Article dated July 22, 2007, located at http://www.baseballhall.org

3 Boston Herald, August 13, 1978

4 Rick Huhn. The Sizzler (Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press, 2004), 18-27; 270-271

5 Lee Lowenfish, Branch Rickey – Baseball’s Ferocious Gentleman (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007), 529-530

6 Ibid.

7 Sports Illustrated, August 8, 1960, 26

8 The Sporting News, November 24, 1962, 29

9 Pittsburgh Press, November 20, 1962

10 Sports Illustrated, July 22, 1963, 34

11 David Halberstam. October 1964 (New York: Random House, 1994), 334

12 Phil Pepe. Undated article in Groat’s player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

13 The Sporting News, May 21, 1966, 20-21

Full Name

Richard Morrow Groat

Born

November 4, 1930 at Wilkinsburg, PA (USA)

Died

April 27, 2023 at Pittsburgh, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.