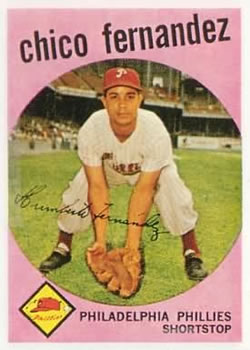

Chico Fernández

Shortstop Humberto “Chico” Fernández played the game with flair. It was a flair that endeared him to fans and fellow players, but often saw him at odds with his many managers. He was a daring, some would say reckless, baserunner.

Shortstop Humberto “Chico” Fernández played the game with flair. It was a flair that endeared him to fans and fellow players, but often saw him at odds with his many managers. He was a daring, some would say reckless, baserunner.

Playing for the Detroit Tigers, he showed that special flair in the second game of a July 4, 1961 doubleheader at Yankee Stadium. The Yankees and Tigers were locked in a mid-summer battle for first place in the American League. With the bases loaded and two out in the ninth inning of a 2-2 tie, Tiger slugger Rocky Colavito came up. Fernández was on base. “When I was on second,” Chico later said, “I noticed [Yankee right-hander Rollie Sheldon] wasn’t watching the baserunners. So I thought I might have a chance to steal home if I got to third.”1 Chico took off for home as Sheldon delivered. Colavito ducked out of the way as Fernández dove across the plate safely. Chico’s right hand extended toward the plate as catcher John Blanchard made a futile attempt to apply the tag. The Tigers went on to win the game, 4-3 in 10 innings.

While it could be debated whether the strategy was a wise one, all agreed the play was pure Chico. As Fernández himself said after the game, “It’s a good thing I was safe because if I was out, I would probably be back in the minor leagues.”2

Humberto Fernández Perez was born in Havana, Cuba, on March 2, 1932. He lived with his parents and older brother, Sergio, in one room of a house that the family shared with eight other families. There was one bathroom. Humberto’s father was a bricklayer by profession, who had played amateur baseball. At school Fernández became a star shortstop emulating his idol, Negro League star, Silvio Garcia.3

In 1951, at age 19, Fernández was signed by Dodger scout Andy High and assigned to the Class C Billings (Montana) Mustangs in the Pioneer League. In Billings, he got a crash course in cold weather, English, and living on his own. He also acquired a new name, “Chico,” which the Dodgers brass told him would be easier for Americans to pronounce. “Chico” was a common nickname given to Latin players at the time and it is no stretch to see some racism attached to the moniker. “Chico” means “boy,” an offensive slur used against Black men. In fact, during the time Humberto “Chico” Fernández played professionally, there were several other Chico’s in the professional ranks: Chico Carrasquel, Chico Salmon, Chico Ruiz, and even another Chico Fernández, whose real name was Lorenzo.4 As Fernández put it many years later, “They took away my first name and I was afraid they were going to take away my whole name and I wouldn’t know who the hell I was.”5

Whatever the challenges, the young Fernández performed well at Billings, hitting .284 and showing dazzling defensive skills at shortstop. In 1952, Fernández was promoted to the Class B Florida-International circuit where he was the only person of color on a Miami Sun Sox team that won 104 games. Playing in every Sun Sox game, Fernández hit .261, and showed off his base running prowess with 25 stolen bases. He continued to show that he had major league defensive tools, thrilling the fans with “brilliant” plays at shortstop.6 Because of the hardships Fernández faced as the only person of color on this deep South team (he was often forced to eat in the kitchen and room away from his teammates in segregated sections of the town), the Dodgers changed their policy. At season’s end, they ensured that every one of their minor league affiliates had at least two Black players on the roster.7

In 1953, the 21-one-year-old Fernández was promoted to the Dodgers top minor league affiliate, the Montreal Royals of the AAA International League. He was the youngest player on the team. In Montreal, he was paired with fellow Cuban Sandy Amoros. The two became roommates and friends. Whether it was the language barrier or some other cause, Fernández and Amoros apparently had problems with lateness, missing the team’s train and showing up late on a few occasions. Eventually they were fined by manager Walter Alston.8 This was the beginning of ongoing issues Fernández had with most of his managers. As the Royals regular shortstop, Fernández hit .247, while continuing to display excellent defensive skills.

Back in Montreal in 1954, Fernández showed the Dodgers that he was ready for the major leagues. He hit a solid .282 with 44 doubles, while making all the plays at shortstop. He was named to the International League All-Star team. Over the winter, while Fernández played for the Cienfuegos team in Cuba, as he had done every winter since beginning his professional career, the talk around Brooklyn was that Fernández was poised to replace the 36-year-old Dodger captain, shortstop Pee Wee Reese. Several Brooklyn scouts went down to Cuba to see him play. Fernández put on a show with his speed, defense, and bat.9 He was named the number one player on his Cienfuegos team. By January 1955, he had been added to the Dodger roster and invited to spring training.

At the Dodger spring training venue in Miami in 1955, one of the chief topics of conversation was the competition for the shortstop position. Don Zimmer had been the heir apparent for years, but Fernández came into camp with a reputation as a defensive wizard with the potential to win the starting job if he could hit enough. Over the winter, the Dodgers had shown how much they valued Fernández as a prospect. They asked Cleveland general manager Hank Greenberg, who was seeking a trade for the young shortstop, for $200,000 dollars or hot pitching prospect, Herb Score, in exchange. Greenberg turned them down.10 Fernández stayed with the big club through spring training and made the trip north. Unfortunately, he came down with a 100+ degree fever and was put on bed rest. By the time he recovered, he had been optioned on 24-hour recall to Montreal. He remained in the minors for the entire 1955 season.11 Reese remained the Dodger shortstop and Zimmer made the big club as a utility man.

Fernández responded to the demotion by having his finest minor league season to date, batting .301, with 34 doubles in 140 games. He continued to shine at shortstop. But three sterling seasons at Montreal were still not enough to propel Fernández to the Brooklyn roster. In the spring of 1956, his wizardry at shortstop, speed on the bases, and improved hitting were all on display, but he was still unable to dislodge the now 37-year-old Reese from his starting position or win the utility post. A clue to manager Alston’s reluctance to hand the job over to Fernández appeared in the New York Daily News. Sportswriter Dick Young quoted Alston as saying, “If only Fernández had a little of Zimmer’s desire to play ball.”12 This may have been true. It may also have been true that the Dodgers were already carrying six Black players, and even though Jackie Robinson had broken the color barrier in 1947, major league teams still had an unofficial quota system in place, believing that too many players of color would be bad for business. The demotion so angered Fernández that he threatened to quit and return home to Cuba. According to Chico, “I told (Dodger general manager) Buzzie Bavasi I was going to quit, but he sent Jackie Robinson to talk me out of it. Jackie said, ‘Look Chico, don’t be stupid because Pee Wee has maybe one more year.’”13

Finally, on July 13, 1956, Chico Fernández was called-up to the major leagues. Reese was nursing a sore hamstring and hard luck Don Zimmer had suffered a second beaning and was out indefinitely. Zimmer was first beaned in the minors at St. Paul in 1953; a beaning that had left him semiconscious for 13 days. This second beaning, at the hands of Cincinnati’s Hal Jeffcoat, resulted in a broken cheek. Having Fernández fill in at shortstop allowed Reese to shift to third base, replacing Randy Jackson, while Reese’s hamstring healed. Beyond that Fernández provided infield insurance while Zimmer recovered.

Fernández made his major league debut on July 14, going 0-4 with a walk, in a 3-2 loss at Milwaukee. The next day, Fernández had three singles and scored two runs in the Dodgers 10-8 win over the Cubs in Chicago. His first hit was a second inning infield single to shortstop off right-hander Jim Brosnan. His first stolen base came on July 18 at Cincinnati in a 6-3 win over the Reds. Fernández’s first RBI came one day later when he drove in his former Montreal roommate Amoros during a 7-2 loss to the Reds. On July 22, in the second game of a doubleheader, Fernández demonstrated his excellent bunting skills, successfully executing a suicide squeeze with Amoros scoring from third in a 4-3 Dodger victory over the Cardinals in St. Louis.

After Chico’s brief run of starting activity, Reese returned to shortstop, Jackson returned to third base, and Fernández was relegated to use as a defensive replacement and pinch-runner. He hit his first major league home run, a grand slam off Don Liddle of the Cardinals, at Ebbets Field on August 4 in a 12-4 Dodger win. However, the rest of the Dodger pennant-winning season was pretty quiet for the rookie. Fernández did not appear in the World Series, won by the Yankees in seven games.

Trade rumors swirled around Fernández all through the spring of 1957, but Alston was reluctant to part with the young shortstop unless he could find immediate help for his team. Reese was another year older. While the Dodgers seemed to prefer Zimmer to Fernández as a second option, Zimmer’s health, after two beanings, was in question. On April 5, the Dodgers and Phillies agreed to a trade. The Phils got Fernández, and the Dodgers got reserve outfielder Elmer Valo, $75,000, and four players with little or no major league experience. Phillies manager Mayo Smith proclaimed Fernández his starting shortstop. On Opening Day 1957, Fernández became the first person of color to play for the Phillies, a full 10 years after Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier. Ironically, Chico took the place of another Black player vying for the shortstop job, John Kennedy. Kennedy became the second player of color to play for the Phillies when he appeared as a pinch-runner six days later.

Fernández began his career in Philadelphia well enough, hitting .262 and solidifying the Phillies infield with consistent and sometimes spectacular defensive play. He did commit a ninth inning error that set up the winning run as the Giants defeated the Phillies, 2-1 in the first game of a doubleheader on April 21. He was also prone to occasional base-running gaffes, but all-in-all it was a successful campaign for the first-time major-league regular. Offensive highlights included: A four-hit game with three RBIs against the Cardinals in St. Louis on June 26, a game-winning three-run double that beat his old Brooklyn Dodger mates 5-3 in the first game of a doubleheader on July 7, three stolen bases versus the Cubs in a 1-0 Phillies win in the opener on July 11, and triples to beat the Dodgers in back-to-back games on September 2 and September 3.

One play early in the season, however, probably did the most to endear Fernández to the Philadelphia faithful. The game was played at Connie Mack Stadium on May 25. It was a Saturday afternoon, before a crowd of 22,414 (6,445 paid) Ladies Day and Knothole Gang fans,14 one of the largest of the season. In the bottom of the fourth inning, with the Pittsburgh Pirates leading 4-3, the Phillies rallied. Right fielder Bob Bowman led off with a single and Fernández, batting eighth, also singled with Bowman going to third. That brought up Phillies pitcher Harvey Haddix and also brought out Pirates manager Bobby Bragan to make a pitching change. Left-hander Bob Smith was brought in to face the lefty-swinging Haddix. Haddix struck out, but Richie Ashburn then singled on a hit-and-run to drive in Bowman, tie the score, and send Fernández flying around to third.

With the feisty Fernández dancing off third, Granny Hamner took a called third strike. Fernández, however, saw that the lefty Smith was paying close attention to the speedy Ashburn at first, but not checking on him at third. Phils slugger Stan Lopata stepped in and as Smith came set, Fernández took off for the plate. The flustered Smith hesitated and threw late to catcher Dick Rand, who could only trap the low pitch and watch as Fernández slid across the plate with the go-ahead run. Home plate umpire Bill Baker flashed the safe sign. Fernández rose, dusted himself off and ran smiling to the home dugout to the waiting congratulations of his teammates and the delighted cheers of the crowd. The unnerved Smith. Lopata slammed one over the left field fence for a two-run homer and the Phillies waltzed to an 8-6 victory. Phillies fans, not used to this exciting brand of play, warmed to their daring new shortstop on the spot and whenever he got on base the stands would fill with the rhythmic chant, “Go, Chico, Go”15

Fernández opened the 1958 season as the unquestioned starter at shortstop for a Phillies team that had exceeded expectations in 1957. They contended for the pennant (they were 12 games over .500 on July 30 and only 3 games behind the league leading Cardinals, before fading in August) and finishing with a .500 record 77-77. But 1958 did not go well for the Phillies or for their flashy shortstop. Fernández slumped at the plate and was hitting only .191 by the All-Star break. His play in the field suffered also, as the Phillies finished last in the league in double plays, much of that laid at Fernández’s feet because of his weak throws to second on the front end of would-be double plays. A managerial change did not help Fernández, either. In July, Eddie Sawyer, former Whiz Kid manager, came out of retirement to replace Mayo Smith, but the team did not improve, finishing 69-85 and last in the eight-team league.

At spring training in 1959. Fernández was still considered the leading contender to be the starting shortstop, even though the Phillies acquired shortstop Joe Koppe from Milwaukee on March 31. Fernández did indeed begin the season as the starting shortstop, but by the end of May with Fernández experiencing fielding problems, Koppe had taken over the position. “The manager didn’t like me,” Fernández later said. “He was prejudiced and so I was benched.”16 As early as May 12, Fernández asked to be traded.17 For his part, Sawyer thought that Chico was playing lackadaisically and earned the benching. Whatever the reason, Fernández virtually disappeared during the latter half of the 1959 season. He did not appear at the plate after June 7 and had only four game appearances (two as a pinch-runner) after June 22. Fans began to ask if he was still on the team. Clearly, the Phillies, or at least Sawyer, had soured on the shortstop. Sawyer said, “He has never shown me he wants to play.”18

Whatever Sawyer’s feelings, there were no shortage of bidders for Fernández’s services. He was finally traded to the Detroit Tigers in December 1959. Cleveland Indian general manager Frank Lane, who was in on the bidding war for Fernández said, “Detroit has made a darn good deal for itself.”19 Detroit manager Jimmy Dykes played down concerns about Fernández’s attitude and said he expected Chico to be his starting shortstop for the 1960 season.20 Perhaps in celebration of his escape from Philadelphia, and perhaps as a harbinger of things to come, Fernández stole home in a December 23 game to bring Almendares a 1-0 win in a Cuban Winter league game.

True to Dykes’ expectations, Fernández did indeed become the starting shortstop for the Tigers for the next three years. As in Philadelphia, he was the first Latin regular position player on the Tigers (Ozzie Virgil had been with the Tigers in 1958 but had only started 47 games at third base). While he started slowly with the bat, Dykes’ patience and confidence in Fernández seemed to have the desired effect. The defensive specialist was often described as a “moody Latin” or “controversial.” But after a few weeks he won over the fans and the newspaper scribes as well, by providing the “best shortstopping they’ve had in years.”21 In May, the Tigers acquired Amoros from the Dodgers to provide Fernández with a roommate and fellow native Spanish speaker. At about the same time, Fernández’s hitting took off. By June, The Sporting News, noting his great crowd appeal, declared Fernández to be “Detroit’s most exciting player.”22 For his part Fernández simply said, “The people in Detroit are nice to me; that is why I hit so well.”23

The era of good feelings did not last long, however. On August 3, the Tigers and Cleveland Indians pulled off one of the more unusual trades in baseball history, swapping managers. Tigers manager Dykes was sent to Cleveland for their manager, Joe Gordon. When Dykes left, Fernández lost his biggest advocate in the Tiger organization. Chico’s hitting fell off in the latter half of the season and eventually he was benched by Gordon. Reports around the Tigers indicated that Fernández was a “disgruntled” player, but Gordon shrugged them off telling reporters that Fernández was “tired” from playing both summer and winter baseball.24 For the season, Fernández hit .241 with 13 stolen bases.

Prior to the 1961 season, Fernández got a break when Gordon quit as Tigers manager, saying the team was “as bad as it is.”25 New manager Bob Scheffing addressed the Fernández controversy by stating he was looking forward to working with Chico, “There’s no reason we shouldn’t get along well,” Scheffing said, noting that he was familiar with Fernández’s talent from his time in the National League.26 The relationship got off to a bumpy start when Fernández was benched for “lackadaisical” play during spring training.27 Then Chico made an error leading to three unearned runs in the Tigers’ Opening Day loss to the Indians. Fernández righted himself, however, with a four-hit game on April 26, which included three RBIs and a double. The hit went off Whitey Ford’s kneecap. Fernández held his starting position on a Detroit team that was exceeding all expectations, their run at the pennant and the mighty Yankees punctuated by Fernández’s daring steal of home on July 4. Eventually the Tigers fell short, finishing second, eight games behind the Yankees, but not until they put up 101 victories, their most wins since 1934. For his part, Fernández hit .248, stole eight bases, and made 11 fewer errors at shortstop.

In late September 1961, the Detroit Free Press reported that the Tigers had had it with Fernández and were seeking a blockbuster trade for Chicago Cubs All-Star shortstop Ernie Banks.28 Despite the rumors and reported lack of confidence, Fernández was the regular shortstop when the Tigers reported to spring training in 1962. Fernández had a terrific spring that had reporters lauding his attitude and fielding prowess. When the regular season started, Chico showed off a side to his game that no one had seen before.

In six seasons in the big leagues, Fernández had never hit more than six home runs in a season and had a grand total of 19 home runs for his career. For some reason he found his power stroke in 1962, slamming homer after homer into the left field stands. The display was so impressive that after he stroked his fourth of the season, a solo shot off Early Wynn of the White Sox, Detroit Free Press reporter Joe Falls started calling him “George Herman Fernández.” Chico joked that he was “just trying to keep up with Rocky,” referring to Colavito, the Tigers vaunted slugger who hit his fourth on the same day.29 By season’s end Chico had more than equaled his prior career total, slugging 20 home runs. He also had 59 RBIs and 10 stolen bases to go with a .249 average. It was Fernández’s finest season in the majors, but the Tigers fell to 85-76 in fourth place.

In the fall of 1962, Fernández accompanied his Tiger teammates on a six-week, 21-game barnstorming trip to Japan, Korea, and Okinawa. Fernández played well in Japan and was the Opening Day shortstop for the Tigers in 1963. He got off to a slow start offensively, however, and the Tigers decided to go with a youth movement, replacing Fernández at short with rising star Dick McAuliffe. On May 9, the other shoe dropped, and Chico was dealt to the New York Mets in a three-way deal with Milwaukee. The headline in the Detroit Free Press read, “Tigers Get Rid of Chico.”30 Fernández had a few starts with the Mets, and hit well, but he had slowed in the field and never established himself in New York. In late July, he was optioned to Seattle in the Pacific Coast League. A September call-up by the Mets would mark the last major league action of Fernández’s career.

Fernández started the 1964 season at the Mets AAA affiliate in Syracuse before being traded to the Chicago White Sox. The Sox assigned him to their AAA team in Indianapolis. Fernández played the 1965 season in Japan, but performed poorly, getting into only 52 games before being released for not hitting. The 1966 season was a marked improvement, as he played in Mexico for the Reynosa Broncos, hitting .326 with 11 home runs. By this time, Fernández was making his year-round home in Detroit. He dropped into the locker room at Tiger Stadium to see his old teammates and brag that in the Mexican League he was batting fourth in the order. He concluded his professional career with two years as a utility infielder at Tacoma, the Chicago Cubs affiliate in the Pacific Coast League.

At home in Detroit, Fernández became a salesman for Metropolitan Life. In 1970 he was also able to reunite with his parents and his brother who had been trapped in Castro’s Cuba. They all moved in with him in a house on Michigan Avenue about a mile from Tiger Stadium. Active in the Latin American Community, Fernández joined the Latin Americans for Social and Economic Development where he supported the development of youth programs. In 1994, he married Lynn Roxbury and moved to Florida. He died there at the age of 84 on May 19, 2016.

Humberto Fernández was a trailblazer as the first player of color on the Philadelphia Phillies. He was also the first Latin regular position player on the Tigers. He recalled his first year in Detroit. He was required to eat in the kitchen of restaurants or live in an old, converted Army barracks outside of Tigertown in Lakeland, Florida. He often was required to room alone on road trips if there were an odd number of players of color on the team. He was justifiably proud of his contributions to opening opportunities for Latin players. He said, “I can tell you I went through some hell, but I just loved baseball.”31

Fernández’s flair and exuberance made him a fan favorite in Philadelphia and Detroit, but he often found himself in the doghouse with management for what they viewed as “moodiness” or lack of desire, or competitiveness. The racism that Fernández faced as a barrier breaker may have spilled over into his managers’ judgment of his attitude.

Whatever his problems with managers, his friend with the Tigers, Rocky Colavito, had a different opinion. “Chico was a damn good player and a good guy,” Colavito told the Detroit Free Press’ Bill Dow. “Who the hell would expect a guy to steal home with the bases loaded, two outs, and the clean-up batter up [at the plate]? He did the unexpected and Chico was no dummy.”32

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Andrew Sharp and Bruce Harris and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Notes

1 Joe Trimble, “74,246 See Yankees, Tigers Divide,” New York Daily News, July 5, 1961: 74.

2 Bill Dow, “As First Starting Latino for Tigers, He Blazed Trail,” Detroit Free Press, June 13, 2016: B5.

3 Bill Dow, “Fernandez Paved Way as Tigers’ First Latin Position Player, Detroit Free Press. August 1, 2015, https://www.freep.com/story/sports/mlb/tigers/2015/08/01/detroit-tigers-chico-fernandez-first-latino-player/31009435/.

4 Anthony Salazar (sabrlatino), SABR Baseball Card Research Committee. “‘Chico’ means little boy, not ballplayer,” February 2, 2017, https://sabrbaseballcards.blog/2017/02/06/chico-means-little-boy-not-ballplayer/.

5 Dow, “As First…”

6 Jimmy Burns, “Negro Players Well-Received in Fla.-Int.” The Sporting News, May 21,1952: 34.

7 “Havana’s F-I Cubans Shift to Key West,” The Sporting News, April 15, 1953: 33.

8 The Sporting News, July 29, 1953: 28.

9 Pedro Galiana, “Fernandez Leading Man in Cuba Show Before Brook Bosses,” The Sporting News, November 10, 1954: 23.

10 Oscar Rule, “From the Rule Book,” The Sporting News, April 27, 1955: 15.

11 Dick Young, “Diamond Dust — Lennon Farmed by Giants,” New York Daily News, April 14, 1955: 194.

12 Dick Young. “Showing of Newcomers May Force Out Shuba,” New York Daily News, March 21, 1956: 25

13 Dow, “Fernandez Paved Way…”

14 Allen Lewis, “Lopata Homers as Phils Beat Pirates, 8-6,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 28, 1957: 61.

15 Dow. “Fernandez Paved Way…”

16 Dow. “Fernandez Paved Way…”

17 Allen Lewis, “Unhappy Chico Asks to Be Traded,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 12, 1959: 34.

18 “Chico Stays in Shape for Winter Ball,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 9, 1959: 53.

19 “Phillies Swap Chico to Tigers,” Philadelphia Inquirer, December 6, 1959: 1

20 ”Phillies Swap…”.

21 Watson Spoelstra, “Dykes Sweet Talk Turns Tigers into Slashing Maulers,” The Sporting News, May 4, 1960: 4.

22 “‘Everybody Nice to Me,’ Chirps Chico Explaining Batting Binge,” The Sporting News, June 29, 1960: 18.

23 “Everybody Nice…”

24 Watson Spoelstra, “Hill Aces, Farm Phenoms Brighten Bengals Future,” The Sporting News, September 14, 1960: 11.

25 Watson Spoelstra, “Heat on DeWitt After Gordon Quits Bengals,” The Sporting News, October 2, 1960: 7.

26 “Restoring ‘Pride of Performance’ Scheffing’s First Tiger Target,” The Sporting News, November 30, 1960: 34.

27 Joe Falls, “Chico Benched as Tigers Win,” Detroit Free Press, March 29, 1961: 29.

28 “Big Off-Season Trade for Shortstop is Brewing,” Detroit Free Press, September 22, 1961: 59.

29 “Bruton giving that Something Extra,” Detroit Free Press, May 23, 1962: 39.

30 “Tigers Get Rid of Chico,” Detroit Free Press, May 10, 1963: 41.

31 Dow, “Fernandez Paved Way…”

32 Dow, “Fernandez Paved Way…”

Full Name

Humberto Fernandez Perez

Born

March 2, 1932 at La Habana, La Habana (Cuba)

Died

June 11, 2016 at Sunrise, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.