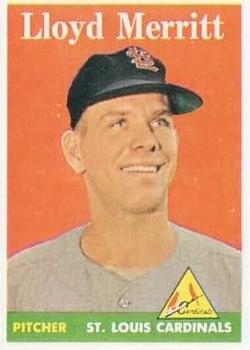

Lloyd Merritt

The story of a hometown boy making good is firmly entrenched in baseball lore. Lloyd Merritt was born and raised in St. Louis, guided his American Legion team to the national championship game, and led the Cardinals in appearances in 1957, the crafty sinkerball reliever’s only season in the big leagues during his nine-year professional career. After more than two decades away from baseball, he came back to the Cardinals as a minor-league manager in the early 1980s and also scouted for two other organizations.

The story of a hometown boy making good is firmly entrenched in baseball lore. Lloyd Merritt was born and raised in St. Louis, guided his American Legion team to the national championship game, and led the Cardinals in appearances in 1957, the crafty sinkerball reliever’s only season in the big leagues during his nine-year professional career. After more than two decades away from baseball, he came back to the Cardinals as a minor-league manager in the early 1980s and also scouted for two other organizations.

Lloyd Wesley Merritt was born on April 8, 1933, in St. Louis, the only child of Howard and Viola Merritt. The Merritts divorced when Lloyd was still a toddler. Mother Viola worked in a metal products factory and raised Lloyd in the shadows of the St. Louis Cardinals and Browns. “[We] lived on Ashland Avenue, which was just about 1½ miles west of Sportsman’s Park,” Merritt told the author about growing up. “My favorite team was the Browns. I was a member of the Browns’ knothole gang and went to lots of games. It was convenient — we’d just walk to the ballpark. We were able to get into the game for free.”1

While attending Mark Twain elementary school, young Lloyd began playing baseball for a local church team when he was 12 years old. “I was a shortstop,” he explained, “but was such a terrible hitter that I was switched to pitcher.” Merritt discovered his passion and calling. With little guidance and coaching, he experimented with different kinds of pitches. “By the time I was in high school, I had mastered a curveball. That was the best pitch to have against young people and helped my career because I didn’t throw that hard.”

Merritt attended Beaumont High School, located a mile west of Sportsman’s Park, directly across from Fairgrounds Park, and on the property where Robison Field, the former home of the Cardinals, had stood. An athletic, 6-foot-tall teenager, Merritt excelled on the hardwood as a sharp-shooting guard, but made his name on the diamond. Beaumont High School had a national reputation for producing professional baseball players. No fewer than 11, including Merritt, made it to the big leagues in the 1940s and 1950s, including All-Stars Pete Reiser and Roy Sievers, while another, Earl Weaver, became a Hall of Fame manager. As a junior, Merritt took the mound for the first time in Sportsman’s Park to lead the Blue Jackets to the St. Louis public school championship in 1950. That summer he made national headlines by leading Stockham, his American Legion team, to the national championship game in Omaha. “Sometimes one is afraid to heap too much praise on a 17-year-old,” opined St. Louis sportswriter John J. Archibald about Merritt’s extraordinary pitching. “The quiet, mild mannered Merritt has been the pitching machine that has probably done more than any one player to make this team a champion.”2 It was the first time a St. Louis area team had made it to the American Legion title game. Even though Stockham bowed to a powerhouse from Oakland, California, Merritt’s performances, filled with low-hit and double-digit-strikeout outings, put him on the radar of baseball scouts throughout the big leagues.3

Merritt’s development was followed closely by St. Louis-based scout Lou Magoulo, who had signed Sievers for the Browns but had moved to the New York Yankees.4 After graduating in 1951, Merritt was invited to participate in a Yankees tryout camp that Magoulo and scout Tom Greenwade (who signed Mickey Mantle) organized in Springfield, Missouri, in June. “The Yankees made me an offer at the end of camp and I signed,” said Merritt. His bonus was $5,000 and not $25,000 as some newspapers reported. (“That would have been nice,” joked Merritt.)5 The Yankees also signed four of Merritt’s Stockham teammates, as well as future All-Star Norm Siebern and Jerry Lumpe.6

“I never really thought about playing in the big leagues,” admitted Merritt, “but I wanted to play professional ball. I came home, bought a car, and headed to Joplin.” Surprised to be assigned to the Miners in the Class-C Western Association instead of a Class-D league where the Yankees typically placed their signees, the 18-year-old joined the club in mid-July and posted a 5-5 record, logging 68 innings. He also met another teenage Yankees farmhand, Whitey Herzog, who’d later play an important role in his baseball career.

Merritt enrolled in the Missouri School of Mines in Rolla (later known as Missouri S&T), where he played on the basketball team. A quick guard with a deft touch, Merritt continued to play semipro hoops well into the 1950s. He later transferred to Washington University in St. Louis in the winter quarter 1952, and continued his education at the University of Missouri in Columbia in subsequent offseasons.

Reassigned to Joplin in 1952, Merritt started off slowly, but finished with a bang. As the Miners rolled to the regular-season title and postseason championship, Merritt tossed consecutive two-hit shutouts against the Salina Blue Jays.7 He won nine of his last 10 decisions to finish with an 11-7 record and a 3.34 ERA in 143 innings.8

Coming off their fourth of five straight World Series titles, the Yankees invited Merritt to their Instructional League camp, which took place in February in St. Petersburg prior to the start of 1953 spring training. The Yankee coaching staff evaluated and worked with the club’s top prospects. Merritt recalled that pitching coach Jim “Milkman” Turner was “especially helpful.” “He saw that I gave away my pitches on the curveball and fastball. He helped me hide my pitches and also worked with me on my mechanics.”

Merritt was promoted to the Norfolk Tars in the Class-B Piedmont League, where he experienced the most transformational season in his professional baseball career. “Originally, I had a three-quarter delivery and was never a hard thrower,” explained Merritt. “When I went to Norfolk, the manager was Mickey Owen, who had been a catcher for the Cardinals and the Dodgers. Owen wanted me to change my pitching motion. What he did is probably the reason I made it to the big leagues. He wanted me to throw the ball with the seams and not across the seams as I was doing. He also had me lower my arm angle to a side-arm position.” Merritt’s early-season makeover was profound. Local sportswriter Paul Duke opined that Merritt “didn’t rate much space in (preseason) stories, but emerged as the best pitcher on the team and league.”9

“It was amazing,” said Merritt about his new sinkerball approach. “All I did was throw the ball low like Owen wanted and batters just hit the ball into the ground. That change gave me a chance to make it to the big leagues. I had a pretty good breaking ball, but Owen made my career.” In his most productive season in Organized Baseball, Merritt went 20-5 with a 2.44 ERA in 225 innings to help the Tars to the league title. He won two more games in the club’s postseason championship run.

Merritt remained a sinkerball pitcher and threw to contact for the rest of his career. “I laugh when I see pitchers today going to the outside on a 2-and-0 count,” he said. “I told my catcher to put the mitt in the middle of the plate. I’m throwing strikes and hope that I get the batter out.”

The excitement of 1953 contrasted sharply with the uncertainty of 1954. Merritt was promoted to the Yankees’ top farm club, the Kansas City Blues in the Triple-A American Association; however, with his draft status during the height of the Korean War in flux, it was unclear which uniform he’d be wearing in April: The Blues’ or Uncle Sam’s.

While working out at Saint Louis University with the Billikens’ legendary trainer Bob Baumann in late winter, Merritt injured his ankle. The injury continued to bother him during the Yankees instructional camp and then in spring training with the Blues in Lake Wales, Florida. Given the injury and the Blues’ surfeit of more experienced starters, Merritt was converted into a reliever. “The transition to a relief pitcher was not as difficult as you might think,” claimed Merritt. “I liked the challenge.”

Merritt made just 12 appearances with the Blues before the draft board summoned him in May. The Yankees subsequently transferred him to the Quincy (Illinois) Gems in the Class-B Three-I League so that he could be closer to home. He made five starts before his induction into the Army in late June.

For 21 months, until spring 1956, Merritt was stationed in Camp Chaffee, Arkansas, where he rose to the rank of corporal. Merritt was a clerk-typist and in his spare time played on the camp baseball team, which was “not a competitive, traveling team like those at Fort Leonard Wood (in Missouri) and Fort Jackson (in South Carolina),” he explained. Merritt saw more action on the hardwood, where his camp team, led by future NBA Hall of Famer Sam Jones and Al Bianchi, won the 4th Army tournament at Fort Hood (Texas) and then the All-Army championship at Fort Leonard Wood.

At the height of his baseball career, Merritt’s stint in the Army came at the most inopportune time. “I lost two years,” he said matter-of-factly. “I never really got back to where I was before the service, and I don’t use that as an excuse.”

In 1956, a rusty, 23-year-old Merritt was assigned to the Birmingham Barons in the Class-B Southern Association. “I didn’t pitch real well, then I got into a groove late in the season,” said Merritt, who finished with a 4.71 ERA in 65 innings, all in relief. At the time, however, he did not realize the ramifications of that late-season surge.

To recapture his form, Merritt played winter league ball for the first time, joining Kola Roman in the Colombian League. “There were two teams in Cartagena and two in Barranquilla,” explained Merritt. “We’d travel back and forth between the two cities. There was some good pitching there. Jim “Mudcat” Grant and Earl Wilson played for Willard.” Early in the season, Merritt got some surprising news. “After pitching one day, I was told that I had just gotten drafted by the Cardinals.” The club selected him on December 3 in the Rule 5 draft, the final of just eight players chosen that year and the Cardinals’ second selection after Bob Smith. “Apparently one of the reasons I got drafted was that [GM Frank “Trader”] Lane wanted a player from St. Louis on the Cardinals to generate attention and fan interest.” One of top the starters in the circuit, Merritt posted a stellar 2.26 ERA in 123 innings for Kola Roman despite a lackluster 6-8 record.10

Merritt cut his season short a few weeks to return to St. Louis for another big change. On January 26, 1957, he married Jimmie Faye Barker, whom he had met while playing in Birmingham. They had two daughters, Lori and Lisa. “My best friend, Norm Siebern, was the best man at the wedding,” recalled Merritt.

Six years after signing his first professional contract, the now 24-year-old Merritt finally made it to his first big-league spring training, joining the Cardinals in St. Petersburg. “It was scary,” he admitted. “I got to camp with players you watched and never expected to play with.” Merritt quickly discovered a tight-knit, yet generous squad. “The players welcomed me and helped me tremendously.” Merritt pointed to Stan Musial, vocal team leader Ken Boyer, and also pitcher Larry Jackson, who would emerge that season as the Cardinals ace. “He was the one I stayed around the most and talked pitching to.”

If Lane wanted Merritt for good copy, he got his wish. Merritt’s exploits as a 17-year-old Legion hurler were fresh in the minds of many St. Louis sportswriters. J. Roy Stockton of the Post-Dispatch praised the Cardinals prospect as a “serious young righthander with a good curve … and unusual control for a rookie.” He compared him to another rookie, Johnny Beazley, who won 21 games for the World Champion Redbirds in 1942, opining that Merritt has “cool determination, the same self-confidence.”11 Jack Hernan of the Globe-Democrat described Merritt as “a throwback to the old school” and a “rookie of distinction.”12

Despite a fourth-place, first-division finish, the Cardinals (76-78) were coming off a disappointing season in 1956 and were in desperate need of pitching. The staff’s ERA (3.97) was second highest in the NL. After a productive spring training, Merritt earned a spot in manager Fred Hutchinson’s bullpen. He was nominally the third option behind an offseason acquisition, knuckleballer Hoyt Wilhelm, and converted starter Willard Schmidt.

“I was scared to death when I made my major-league debut at Sportsman’s Park,” admitted Merritt about taking the mound on April 22, 1957. “I never thought I’d make it. On the first pitch I stumbled and fell because I was so shook up. We were playing the Cincinnati Reds and I came in the sixth inning and face a bunch of sluggers [Frank Robinson, Gus Bell, Wally Post, and George Crowe]. What a great thrill to know that you were playing at Sportsman’s Park after growing up so close to it.” Nerves aside, Merritt tossed two scoreless innings, yielding just a hit, and fanned one.

Merritt seemed to have the ideal temperament and physical attributes for a relief pitcher. “I didn’t need to warm up much to get ready,” he explained. Cerebral and inquisitive, Merritt picked the brains of teammates and opponents. “I asked Eddie Roebuck, who was a sinkerball pitcher for the Dodgers, what he did when he didn’t pitch for a while. He told me that he pitched batting practice. I didn’t want to enter a game and overthrow or be extra strong. I just wanted to throw the ball low.”

On May 5 at Connie Mack Stadium in Philadelphia, Merritt replaced starter Willard Schmidt and hurled five scoreless innings while the Cardinals overcame a 4-0 deficit to win, 8-4, giving Merritt his first big-league win. It also proved to be his only victory of the season and in his major-league career. Nonetheless, Merritt had a productive campaign and led the staff with 44 relief appearances with a robust 3.31 ERA in 65 innings, and seven retroactively awarded saves.13

Led by the majors’ best-hitting team (.274 average), the Cardinals surprisingly challenged for the pennant for the first time since 1949. They were in sole possession of first place as late as August 4, a game ahead of the Milwaukee Braves, before the bottom fell out. “We lost a bunch of games to the Cubs [six straight as part of a nine-game losing streak] and fell out of first, and never got our momentum back,” said Merritt. While the Redbirds fought back, moving to within 2½ games of the eventual World Series champion Braves on September 15, Merritt had his busiest month in September, appearing in 11 games. The Cardinals’ second-place (87-67) finish was their highest since 1949, though eight games behind the Braves.

Asked about his most memorable game, Merritt was quick to respond. “Other than my debut, it was against the Braves in front of a large crowd [in a Sunday doubleheader on May 12]. I came in with the bases loaded and no outs in the sixth inning. My first three pitches were balls and then I struck out Johnny Logan. I got [Bill] Bruton to fly out, and [Del Rice] out. I don’t know why I remember that game so well. Maybe because the capacity crowd was so excited.”

In the offseason, Merritt played for Havana in the Cuban Winter League. “Havana was a special city,” recalled Merritt “On Sundays we’d go to the Hotel Nacional to eat. We all had apartments in the city, close to the beach.” But it wasn’t just Cuba Libre cocktails and cigars. Merritt excelled on the mound, tossing 148 innings with a 2.61 ERA and splitting 14 decisions, and was named to all-star squad in the Cuban vs. American all-star game.14 I believe he’s coming of age,” said GM Lane who personally scouted Merritt during a stretch of three straight complete games in which he allowed just three runs.15

The future looked bright for the 25-year-old Merritt when he arrived at the Cardinals camp after pitching practically year-round for the last two years. His adjusted ERA in 1957 was 120 (20 percent better than league average) and he was in great health.16 “It was disappointing in spring training,” said Merritt. “I had pitched well in Cuba and felt that I was about to break out. Then came spring training and I didn’t pitch well.”

At the end of camp, Merritt was optioned to Omaha in the Triple-A American Association and never made it back to the big leagues. “I wasn’t pitching that well for the Cardinals to bring me back,” Merritt stated honestly. After just nine appearances, Merritt dropped a level, to the Houston Buffaloes in the Double-A Texas League, where he had the chance to pitch regularly. He made 52 appearances and went 10-3 for the last-place club (66-95), but also posted a high 4.36 ERA in 95 innings.

Hoping to resuscitate his prospects, Merritt was back in winter league ball in the 1958-1959 offseason, this time with Caguas-Guayama in Puerto Rico. Along with a teammate, 21-year-old Juan Pizarro, Merritt (7-3 and the league’s lowest ERA, 1.63 in 94 innings) helped player-manager Vic Power’s club to the tournament championship series, which they lost to Santurce.17

Santurce added Merritt to its squad for the annual Caribbean Series which pitted the champions from Cuba, Panama, Puerto Rico, and the Dominican Republic. All of the games took place at UCV Stadium in Caracas, Venezuela. On February 13, 1959, Merritt and Orlando Peña of the eventual champion Cuban team engaged in a pitchers’ duel, both tossing seven-hitters with Cuba winning, 1-0.18 Puerto Rico (3-3) finished in third place.

Merritt loved playing winter ball — in Colombia, Cuba, and Puerto Rico — and stressed the high quality of play and the seriousness of the ballplayers. He also mentioned the benefits of travel, culture, and especially money. “The pay during winter ball was better than the big leagues for me. I made $6,000 with the Cardinals in 1957. I think I made about $7,000 in Cuba.”

Merritt needed to keep his bags packed in 1959. After playing in Cuba and Venezuela, he began the season back with Houston before he was sold to Rochester, the Cardinals’ affiliate in the International League. On June 15 he was traded along with Chuck Essegian to the Los Angeles Dodgers for utilityman Dick Gray. Merritt was assigned to the Spokane Indians in the Pacific Coast League, where he got off to a robust start. Local sportswriters described him as a “relief ace,”19 and praised his “sinking screwball” and “curve.”20 Said Merritt, “There was some discussion that I might be called up,” but he added that Chuck Churn got hot and was promoted. On December 3 Merritt was shipped to the Baltimore Orioles as part of a five-player deal and subsequently assigned to Vancouver in the PCL.

After one appearance with Vancouver in 1960, Merritt was sold to the Little Rock Travelers in the Double-A Southern Association. In what proved to be his final season in professional baseball, Merritt appeared in a team-high 49 games. In the offseason, the 27-year-old Merritt was given his unconditional release.

“I had made up my mind that I was done with baseball,” said Merritt. “I turned down a chance to pitch in Hawaii (with the PCL Islanders).”

A lifelong St. Louisan, Merritt embarked on his post-baseball life with his wife and two daughters; however, the transition was not easy. “I bounced back and forth for two or three years not knowing what I wanted to do,” recalled Merritt. “I had a job selling life insurance and worked for Firestone. Finally, I went to work for a roofing company.”

“My biggest mistake was not staying in baseball after my career was over,” admitted Merritt. “I should have gone into managing and scouting.” Merritt never lost his passion for baseball. Into the mid-1960s, he played in the competitive semipro St. Louis Municipal League and maintained his close friendships with former teammates. More than 20 years after leaving professional baseball, Merritt desired to get back into the game.

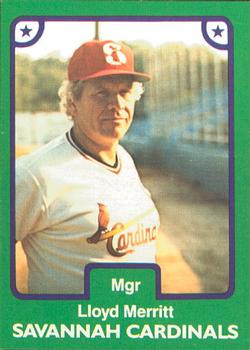

In 1981 Merritt contacted two friends to offer his services and ask for advice: Whitey Herzog, his former teammate from 1951 and the manager and GM of the Cardinals; and Lee Thomas, a classmate at Beaumont High School, who became an All-Star right fielder and was at the time the Cardinals’ director of minor-league operations. “I just went down to the Cardinals’ office and talked to them,” said Merritt.

Despite Merritt’s lack of coaching experience and his two-decade-long absence from the professional game, Herzog and Thomas were sufficiently impressed with Merritt to appoint him manager of Gastonia (North Carolina) in the Class-A South Atlantic League.

Despite Merritt’s lack of coaching experience and his two-decade-long absence from the professional game, Herzog and Thomas were sufficiently impressed with Merritt to appoint him manager of Gastonia (North Carolina) in the Class-A South Atlantic League.

“I was nervous about getting back into the sport after so long,” said Merritt. He credited many people in the Cardinals organization who helped and supported him, from Herzog and Thomas to Jim Fregosi, who became the Louisville Redbirds skipper in 1983. “Fregosi told me that he was amazed how much I knew about the game after being away from it for so long.”

Merritt piloted three different Cardinals affiliates in the Sally League (1982-1984), guiding Savannah to the postseason in 1984. In 1985 he managed Springfield (Illinois) in the Class-A Midwest League. His cumulative record was 269-297. Merritt revealed that his proudest accomplishment was mentoring Vince Coleman with Macon in 1983. The 21-year-old speedster stole 145 bases despite playing in only 113 of the team’s 144 games. “Coleman complimented me later by saying that year was the turning point for him,” recalled Merritt. “He thanked me for giving him the chance to realize his potential.”

Seemingly back in the groove of coaching, Merritt admitted that he made “another big mistake.” “For some reason after four years of managing, I decided to leave the Cardinals and baseball again. I was just a year away from qualifying for my (coaching) pension.”

By this time Merritt had divorced, remarried, and moved to Pittsburgh, where he worked in sales again. However, his heart was still in baseball. Almost a decade later, around 1993, Merritt contacted his old friend Lee Thomas, who at that time was the GM of the Philadelphia Phillies. Merritt became a Phillies scout in 1994. “I scouted amateurs in Pennsylvania and traveled all over the state.” Merritt retired in 2002, but not for good. While living in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, he got in touch with Frank Wren, the Atlanta Braves’ assistant GM. Merritt went back on the scouting trail for two more years (2007-2008), retiring at age 75.

As of 2021, Merritt was retired and living outside of Nashville, in Franklin. He also spent time with his family in Florida.

Last revised: February 11, 2021

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Malcolm Allen and Len Levin.

Special thanks to Lloyd Merritt, whom the author interviewed on December 9 and December 30, 2020, and for subsequent correspondence and discussions to ensure accuracy of the biography.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author accessed Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com, SABR.org, and The Sporting News archive via Paper of Record.

Notes

1 All quotations from Lloyd Merritt are from interviews conducted with the author in December 2020.

2 John J. Archibald, “What Makes Stockham Click? It’s a Balance and Team Smoothness,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 3, 1950: 4D.

3 Merritt and Stockham’s march to the national tournament is a story in its own right. “After losing the first game in the state tournament,” recalled Merritt, “we had to win a tripleheader in Cape Girardeau, Missouri, to advance to the regional tournament.” Merritt tossed a five-hitter and fanned 13 to beat Duncan (Oklahoma), 3-0, to capture the regional tournament in Mason City, Iowa. (See John J. Archibald, “Stockhams Win Regional Tourney; Eye Sectional Title,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 29, 1950: 3C.) At the sectionals, Merritt held a team from St. Paul, Minnesota, hitless for 7⅔ innings, settling for a two-hitter with 10 strikeouts, to help catapult the club into the national tournament. (See Bill Kerch, “Stockham Wins on 2-Hit Hurling by Merritt, 3-0,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, August 24, 1950: 3C.)

4 Just 5-foot-5 and about 110 pounds, Magoulo was a superscout and is credited with signing more than 40 big leaguers, including such Yankees greats as Bill Skowron, Elston Howard, Tony Kubek, Jim Bouton, and Fritz Peterson.

5 “Yanks Pay St. Louis Prep $25,000 for Signature,” The Pantagraph (Bloomington, Illinois), July 20, 1951: 13.

6 Merritt’s Stockham teammates who signed included Pete Pitale, Mark Weir, and Ed Wheatley.

7 Merritt fanned 10 and 9 respectively in the two shutouts. See “Joplin Outlasts Jays 3-0 In Pitchers’ Battle,” Salina (Kansas) Journal, August 10, 1952: 17; and “Only Two Jay Hits As Miners Win Final, 4-0,” Salina (Kansas) Journal, August 17, 1952: 15.

8 “Merritt Had 11-7 Record in ’52,” Press and Sun-Bulletin (Binghamton, New York), March 23, 1953: 11.

9 Paul Duke, “Merritt Proves Mainstay of Tar Box Stall,” Press-Index (Petersburg, Virginia), June 20, 1953: 5.

10 Luis A. Bello, “Fernandez’s .290 Bat Mark High in Colombia Loop,” The Sporting News, February 27, 1957: 27.

11 J. Roy Stockton, “Beaumont High Hurler, Merritt, Stars as Cards Win,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 13, 1957: 42.

12 Jack Hernan, “Young Merritt Stars in 4-3 Cardinals Loss,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, March 23, 1957: 9.

13 Saves have been an official statistic since 1969. For all seasons prior to 1969, saves have been retroactively calculated and awarded.

14 Maximo Sanchez, “U.S. Team Bows to Natives in Cuban All-Star Game, 4-3,” The Sporting News, January 15, 1958: 20. For stats, see the The Sporting News, February 5, 1958: 29.

15 Bob Broeg, “Dealer Frank Stands Pat on Card Hill,” The Sporting News, November 13, 1957: 16.

16 As explained by MLB.com, “ERA+ takes a player’s ERA and normalizes it across the entire league. It accounts for external factors like ballparks and opponents. It then adjusts, so a score of 100 is league average, and 150 is 50 percent better than the league average.” See “Adjusted Earned Ru Average (ERA+),” http://m.mlb.com/glossary/advanced-stats/earned-run-average-plus.

17 “Lloyd Merritt Among Winter League Leaders,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, January 20, 1959: 6B.

18 “Pena Pours It On,” The Sporting News, February 25, 1959: 24.

19 Danny May, “Chris Nicolosi Hurls Indians to Triumph,” Spokesman-Record (Spokane, Washington), June 18, 1959: 22.

20 Harry Missildane,” Rally in the Ninth Short as Indians Lose, 4-3,” Spokesman-Record (Spokane, Washington), July 12, 1959: 23.

Full Name

Lloyd Wesley Merritt

Born

April 8, 1933 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.