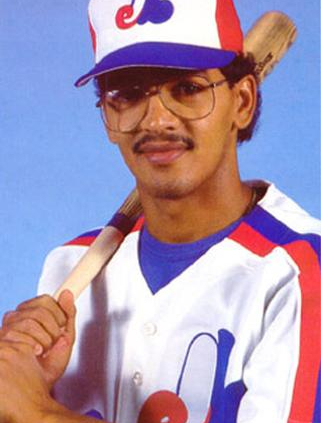

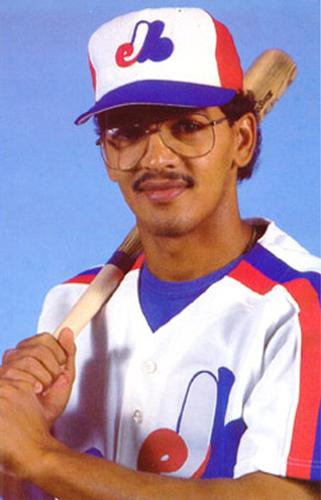

Luis Rivera

To Luis Rivera and his five Latino teammates, it must have seemed like a cruel prank. More than a decade before the dot.com boom made the San Francisco Bay Area an outlandishly expensive place to live, they expected their rented home to be furnished. Wasn’t that common? Their already-stretched $600 monthly salary did not allow for luxury. In the absence of beds, couches, or even chairs, the young San Jose Expos ballplayers set their bedsheets on the floor and attempted to sleep.1

Unlike most other minor leaguers, who dread long road trips on cramped buses, Rivera and his housemates looked forward to such endeavors, as the yellow brick road would lead to a motel with beds. “You could have given up … but I was there to play baseball,” said Rivera in 2021. “You decide what you want to do. Your willpower can help you push forward, or you can use that as an excuse to leave, and then cry about what you could have been. I try not to think about what I could have been, but rather try to do what I want to do.”2

Such was Rivera’s path to the major leagues, which included all or parts of 11 seasons (1986-94; 1997-98), primarily as a shortstop. He also spent 15 years (2006-09; 2013-23) as a big-league coach, in addition to two as an “eye in the sky” scout (2011-12). Although he never managed in the majors, he was a successful minor-league skipper for four seasons.

It all started more than 3,500 miles from San Jose, in the town of Cidra, Puerto Rico, where Luis Antonio Rivera Pedraza was born on January 3, 1964. His father Baudilio owned a business and often worked from 6 AM through 10 PM while his mother Jacinta ran the household.

Young Luis began playing baseball at four years old. “My brothers played baseball, so I tagged along and started to play as well,” he said. “Although I didn’t tell anyone, by the time I was 12 I knew playing professional baseball was my goal.”3 He was never far away from a game, playing basketball or baseball with whatever equipment was available. His brothers Carlos and Iván played for the Cidra Bravos (Braves), the local amateur team.

As the first native of Cidra to play in the big leagues, Luis was proud that others soon followed his trail. Rivera recalled fellow Cidra natives Tony Rodríguez and Luis López: “I’m only about five years older than them,” he said. “When I played, they were youngsters and practiced with me. I got to the majors first and that was also their goal: to reach the big leagues just like I had … and they did as well! A lot of times it’s like that when you’re the eldest in the group, others try to see how you did it and emulate you.”4

When Rivera was approximately 13, he began playing with a team in Guaynabo, a city about 20 minutes away. There he found tougher competition: “I was the little stud in Cidra, clouting big hits, but I had harder times in Guaynabo,” Rivera said. “We won the island championship in the ages 13-14 and ages 15-16 categories and got to play in the United States. I played with Luis Alicea, Tito Stewart, Rico Rossy … seven or eight of us signed professional contracts and three or four of us reached the majors.”5

Once he turned 16, Rivera moved to the Puerto Rico semiprofessional league (COLICEBA, for the Spanish language acronym for Amateur Baseball Central League Federation) and the amateur Double-A Superior Baseball League, where he played with grown men several years his senior. Proving his mettle against this caliber of competition convinced Rivera of his chances to play professionally: “If we had a rainout Saturday morning,” he said. “I’d be at the park in the afternoon running, throwing. … I was always dedicated to baseball. … You can’t just like it, you have to love it.”6

He signed with the Montreal Expos as an amateur free agent on September 22, 1981, soon after graduating from Luis Muñoz Iglesias High School in Cidra. At the time, Puerto Ricans were not subject to the draft and were thus free to sign with any interested team. Montreal scouts Frank Pérez and Danny Menéndez facilitated the deal.7 Unwilling to wait until the following spring, Rivera requested the Expos assign him to the fall instructional league. He continued training during the winter in Cidra.

In 1982, the 18-year-old Rivera played in 130 games for the Class-A San Jose (California) Expos and held his own against peers four years his senior. He hit .258 with little power (three home runs) or plate discipline (only 27 walks in 515 plate appearances). His defense was questionable, with 55 errors in 670 chances. Nevertheless, league managers selected him as the top defensive shortstop in the California League.

San Jose’s partnership with the Expos lasted only a year and the team became an independent outfit in 1983 under the Bees moniker. Thus, Montreal assigned Rivera to its Class-A Florida League affiliate in West Palm Beach. 8 He produced nearly identical numbers in 1983 (.227/.324/.329, 129 games, .928 fielding average) and 1984 (.228/.312/.321, 124 games, .938 fielding average).

The organization was heartened by his progress. Rivera played the entire 1985 season with Jacksonville of the Double-A Southern League and reached career highs in home runs (16) and RBIs (72) in a league-leading 538 at-bats. He was named to the Topps Double-A All Star team.

In 1986, Rivera was assigned to the Triple-A Indianapolis Indians and enjoyed a solid season, especially in the field (he hit an improved but still mediocre .246 in 108 games). Baseball America ranked him as the Expos’ fifth-best prospect, a spot he would also hold in the 1987 preseason ranking.9 However, “since Hubie Brooks, the team’s cleanup hitter, was the shortstop, I figured I wouldn’t have a break until September,” Rivera said.10 Rivera’s opportunity arose suddenly when Brooks tore ligaments in his left thumb. Rivera hesitated to call his parents with the news, since it was already 11 P.M. He recalled that night: “Either they won’t pick up the phone or they’ll be scared thinking someone has had an accident. … What to do? I said to myself, ‘I don’t care, I’m calling them,’ and my mother picked up the phone. My mom was hollering and celebrating. … Even if you strike out four times the next day, it’s still a wonderful feeling. I stayed up until 2 A.M. packing, then took a 6 A.M. flight since it was a Sunday afternoon game. … I landed in New York and took a cab. The taxi driver tells me, ‘Here you are, Shea Stadium,’ and the radio broadcaster happened to arrive at the same time, and he took me to the clubhouse.”11

Rivera debuted hitting second in the Expos’ starting lineup on August 3, 1986, against the eventual World Champion Mets. He grounded out in his first two at-bats against Bob Ojeda but managed a single in his third plate appearance, breaking up Ojeda’s bid for a no-hitter. He advanced to second base on a Tim Raines groundout and scored Montreal’s first run on an Andre Dawson single. He was also instrumental in the team’s ninth-inning comeback; he again singled off Ojeda and scored on another Dawson single. However, the Mets won on a walk-off single by Ray Knight in the bottom of the 10th. In the field, Rivera registered three putouts and seven assists. For the year, he appeared in 55 games for Montreal, and was usually over-matched at the plate (.205/.285/.283).

Although Rivera made the big-league club out of 1987 spring training, he continued to struggle on offense in the early part of the season (3-for-24 in nine games) and was demoted to Triple-A. However, he had little to prove in the American Association (.312/.360/.441 average in 108 games, a league-leading 84 double plays) and was named the best defensive shortstop. He returned to the majors in May (two games, four at-bats) and September (seven games, 2-for-4). The Expos, however, were not sold on Rivera as a long-term solution. Also, being far away from home was hard on him: “I had to work really hard,” he said. “You play every day and you’re away from your family, even though you’re never alone. Even when there was no phone available, God was (and remains) with me. But it was difficult. If it’s hard to reach the big leagues, it’s even harder to stick around, because the competition is fierce.”12

After the season, The Sporting News reported, “Montreal is still looking for an experienced shortstop. But, if necessary, the Expos may go with 24-year-old Luis Rivera, who hit .312 in Triple-A.”13 Roughly a month later, the same publication wrote “since their efforts to acquire a proven shortstop have failed, the Montreal Expos plan to give rookie Luis Rivera a shot.”14 It was hardly a ringing endorsement.

Nonetheless, Expos manager Buck Rodgers viewed Rivera as ready to take over at short that winter. Rivera couldn’t believe it until he came to spring training and saw that incumbent Brooks had been shifted to the outfield.15 Interviewed before Opening Day, Rivera noted he “felt proud to be the regular shortstop this year and hopefully for many years. … I am glad they gave me a chance and I will do my best.”16 He had two hits and scored a run in the Expos’ 10-6 loss to the Mets.

However, his average dipped below the Mendoza Line by mid-May. A four-hit game against San Diego on May 24 – the first of three he would record in the majors – pushed him above .200. Still, his offensive output remained meek. For the year, he appeared in 123 games (.224/.271/.318), typically as the eighth hitter in the lineup.

As the media had expected a year earlier, Montreal sought a veteran for its infield. On December 8, 1988, the Expos traded Rivera and John Dopson to the Boston Red Sox for shortstop Spike Owen (Montreal also received pitcher Dan Gakeler). The deal may not have garnered headlines, but it gave Rivera an opportunity to play in Fenway Park, one of baseball’s most historic places, away from Olympic Stadium’s artificial turf. Rivera was expected to be a solid middle infield option off the bench, backing up veteran Marty Barrett at second base and shortstop Jody Reed, who had led AL rookies with 3.4 WAR in 1988.

Rivera began the 1989 season in Triple-A but was called up in early June once Barrett underwent a knee operation: “I thought I had a good spring, but I knew they had Jody at short and Marty at second and I could not play the other infield positions,” Rivera said. “I did my best in the spring, but I was sent down. When I went to Triple-A, I played hard. I don’t know any other way to play.”17

Rivera went 12-for-32 (.375) in his first 10 games, including four hits against the White Sox on June 18. He enjoyed a 12-game hitting streak and was successful in driving in runners with two outs (13 out of his first 21 RBIs), surpassing expectations.

The Red Sox were elated: “We knew we stole an outstanding shortstop when we were able to get Rivera,” said GM Lou Gorman.18 Manager Joe Morgan, who’d taken over the team from John McNamara in mid-1988, added, “I knew he could play and if we needed him he’d come through and he sure has. The thing I didn’t know was he had a little pop in his bat.”19 Rivera hit .257 and fielded .958 as the team dropped to third place in the AL East, treading water for most of the summer before getting hot late in the season.

He slumped to .225 in 1990 but improved his fielding percentage to .965 in 112 contests at shortstop. The season’s offensive highlight was a grand slam on August 31 in Fenway in a 7-3 win over the Yankees. He had a career-high five RBIs that night.

Boston returned to the postseason but was swept by the Oakland A’s. In the four games, Rivera went 2-for-9 and made a costly error in the third game. Nevertheless, it’s the year he remembers the most: “We had Roger Clemens, we had Wade Boggs, Dwight Evans, Jack Clark, Tony Peña, Carlos Quintana, Mike Greenwell. … It was a good, veteran team.”20, 21

In 1991, he was beaten out by Tim Naehring in spring training for the shortstop job, but quickly regained it after Naehring began the season 6-for-55. Rivera hit an inside-the-park home run on June 21 against the Athletics, atoning somewhat for his poor LCS performance. “As soon as the ball got by (A’s outfielder José Canseco), I was going to run as hard as I could and wait for them to hold me up,” Rivera said. “They never did.”22 The sixth-inning blow was the winning run in Boston’s 3-2 victory.

In early July, Rivera had a “little altercation in the heat of the battle,” according to Morgan, after nearly colliding with left fielder Greenwell in consecutive games.23 Nevertheless, the manager chalked it up to “grabbing of shirts” and nothing serious.24

Rivera established multiple career highs in 1991 (129 games, 414 plate at-bats, 107 hits, 22 doubles, eight home runs) but also led AL shortstops with 24 errors. He went under the knife in the offseason to repair torn cartilage in both his left knee and left shoulder.

He regressed in 1992 (.215/.287./.260 in 102 games) and was limited to 62 appearances in 1993, losing playing time to veteran Scott Fletcher and farmhand John Valentin during two stints on the injured list.

With Naehring as a younger option as a backup infielder, the Red Sox granted Rivera free agency on October 25, 1993. He noted that moving franchises never affected him. “I was only traded during the offseason, so the trades never brought any problems,” Rivera said. “I always had several months to prepare. Once I joined the team, I already knew them, so it wasn’t difficult.”25

Rivera signed with the New York Mets on January 19, 1994. He played in only 32 games during the strike-shortened season, his lowest tally since 1987, but produced with the bat, slashing .279/.367/.581 (144 OPS+). The Mets used him 18 times as a pinch-hitter.

Rivera signed a free agent contract with the St. Louis Cardinals once the strike ended in 1995 but was released within six days. He joined the Texas Rangers organization on May 3, 1995, but was released six weeks later after an uneventful 19 games with Triple-A Oklahoma City (.138/.167/.259).

He rejoined the Mets organization on November 15, 1995. In 114 games with Triple-A Norfolk in 1996, he averaged .225/.290/.357. He then became a free agent once again.

Signed by Houston on January 25, 1997, Rivera appeared in seven games for the Astros (3-for-13) and 124 for the Triple-A New Orleans Zephyrs (.238/.300/.343). He returned to the Zephyrs in 1998 (33 games, .232 average) before his contract was purchased by Kansas City, where he played 42 games down the stretch for the Royals (.247/.302/.292).

Rivera signed a contract with the Anaheim Angels on January 15, 1999. However, he did not make the team out of spring training; thus, his big-league career ended at age 35. Baseball was changing, with a near-fanatical zest for home runs. Even middle infielders were expected to be power hitters, and Rivera’s job offers dried up.

For his career, Rivera batted .233/.291/.333 (71+ OPS) in 781 major-league games. He hit well against Tim Leary (8-for-13), Kenny Rogers (6-for-12), Jaime Navarro (6-for-13), Todd Stottlemyre (8-for-20), Randy Johnson (4-for-10), Alex Fernández (8-for-21), Kevin Brown (7-for-20), Tom Glavine (6-for-8, with two home runs), and Mélido Pérez (6-for-19) but was unsuccessful against Nolan Ryan (0-for-12), Sid Fernández (0-for-12), Jack Morris (1-for-14), Dave Stewart (1-for-14), and Greg Maddux (1-for-9).

Although reputed to be a fine fielder, modern statistics have cast Rivera as a mediocre defender (-12 total zone fielding runs against average) with below-average range. His 42 total errors were the highest among AL shortstops in 1990 and 1991, but his 4.95 range factor per nine innings was third highest in the AL in 1992.

Rivera decompressed from baseball in 1999, his first year away from the game since he was a teenager. Yet he wasn’t quite through as a player. The subsequent winter was the last of his 16 seasons in the Puerto Rico Winter League (1982-83 through 1990-91, and 1993-94 through 1999-00). His .225 career average in that circuit was close to his big-league .233 mark, and he was part of two league champions (1987-88 and 1988-89); as a result, he reached the Caribbean Series twice.

Although his first team, Caguas, played a few minutes from his house, Rivera felt being traded to Mayagüez, on the opposite side of the island, was “the best thing that could have happened to me. I played every day, we won two titles, and made the playoffs several times. … It was a beautiful experience to play with Edgar Díaz, Bobby Bonilla, Ken Caminiti … Tom Pagnozzi, John Cangelosi. We had a chip on our shoulder because every time we picked up the newspaper, coverage focused on (metropolitan area clubs) San Juan or Santurce.”26

Rivera’s keen mind was in high demand, and he soon embarked on a second chapter as a dugout leader. He served as the hitting coach for the Kinston Indians, Cleveland’s Class A-advanced affiliate in the Carolina League, from 2000 through 2002. Among his charges, Grady Sizemore and Víctor Martínez later enjoyed All-Star seasons in the major leagues; the club also included future ace pitcher CC Sabathia.

He next managed the Class-A Lake County Captains of the South Atlantic League (2003-2004, winning the manager of the year award in his first season with a minor-league-leading 97 victories) before returning to Kinston for 2005 as its skipper.

Rivera took over the first-base coach position for the major-league Indians (2006-2009). During that time, the club was best-known for pushing the eventual World Series champions, the Red Sox, to the limit in the 2007 ALCS. He left the organization when manager Eric Wedge was dismissed after 2009 and Manny Acta brought in his own coaching staff.

The Toronto Blue Jays were aware of Rivera’s success and named him manager of the New Hampshire Fisher Cats of the Double-A Eastern League for the 2010 season. The club finished 79-62 and reached the semifinals against the Trenton Thunder. Interviewed during the postseason, Rivera stated his goal: to “develop guys.” He revealed, “When I am watching a big-league game, I am not really watching the game. … I am watching what the managers are doing in those different situations.”27

Rivera’s performance earned rave reviews and general manager Alex Anthopoulos offered him a spot with the big club. In 2011 and 2012 under manager John Farrell, he worked as an “eye in the sky” – a role created specifically for Rivera, to avoid losing him to a rival and to get around Major League Baseball’s strict limit of six uniformed coaches. He fraternized with players during practice and then donned street clothes to scout the opposition and “chart the game. I look for tendencies, pitchers’ tendencies, coaches’ tendencies … stuff like that. … I relate it to John Farrell and the coaching staff.”28 Farrell underscored the importance of such insight, noting, “It’s not just the information he brings us. It’s the way he presents it. He is a very valuable part of this staff.”29

In 2013, Rivera – by then the Jays’ third-base coach, a job he occupied for 11 seasons – gave thanks for the opportunity. “I was glad they gave me the chance to be part of that,” he said. “Maybe that’s the reason that I’m here right now.”30

He prepared early and often, given the wealth of available information. He explained his approach in detail. “The day before we play a team, we get the scouting reports. … I’d go over their reports and learn their batting tendencies, the strength of their outfield arms. … Once I get to the stadium, I look at video clips of the [opponents’] outfielders … the direction, the accuracy,” Rivera said. “I have to study all of those tendencies. You must get to the park early because there is a lot to review and to prepare. I watch a lot of games, especially with new players and new situations. … I find out whether the teams run a squeeze. … I don’t check whether they won or lost, but rather what they might do that I don’t know, that information.”31

Rivera stated he “had always felt loved in Canada. … Toronto is a charming city, like Montreal. People are very kind.”32 He also bemoaned the loss of the Expos: “You always want to remember your first team, and I can’t say I was with the Washington Nationals … even though they inherited (the) Montreal (club),” Rivera said. “It’s a pity the team is no longer with us.”33

Rivera served as the third-base coach for Puerto Rico in the 2023 World Baseball Classic. “I had seen the Classics [as a fan],” he said. “It will be my first opportunity and I was waiting for it. It’ll be an honor to represent the homeland. I never have, except for the Little Leagues, but this is something else. I would have liked to have represented Puerto Rico as a player.”34

Although Rivera worked for the Blue Jays under four different managers, he was never offered the opportunity to lead the team, despite interviewing for the job at least twice. This was part of a pattern of an uneven trend of Latino skippers in the big leagues (zero in 2016, six expected in 2024).35 In fairness, however, it’s noteworthy that fellow Puerto Rican Charlie Montoyo led the Jays from 2019 until July 2022.

The typically soft-spoken and self-deprecating Rivera noted his belief that “the owners hire the person they think is most capable. We wish we had more chances to manage, but it’s a decision they have to make.”36 He added the did not see any particular obstacles for Latin Americans, “as long as they speak better English than me. If they’re capable, if they know the game, if they study the game, if they get along well with American players as well as the Latino players, there are no obstacles. I wish there were more Latino managers in the big leagues, ’because I think there are a bunch of guys that are capable. Why are they not getting the chance? I don’t know.”37

Since Rivera’s comments, three other clubs hired Puerto Rican managers: the Nationals (Dave Martínez, New York-City born to Puerto Rican parents), the Red Sox (Alex Cora), the Mets (Carlos Beltrán, though fired before he donned the uniform due to his involvement in the Astros sign-stealing scandal), and the Astros (Joe Espada).

Rivera, however, remained perched in his third-base box, awaiting his chance. Eventually, however, he announced his retirement after the 2023 season. Toronto named Dominican Carlos Febles, former Red Sox third-base coach, to take his place.

Rivera and his wife Carmen have three children: Carla Michelle, a speech pathologist in Gainesville, Florida; Luis Carlos, a doctor in Puerto Rico; and Yan Carlo, also a shortstop, who was drafted by the Blue Jays in the 36th round of the 2014 amateur draft. Though Yan never played in the minors, opting for college instead, eventually he coached the Lake County Captains, a Cleveland Class A farm team, in 2022. That year, he said, “I remember catching for my dad when he was hitting fungoes.”38 The elder Rivera was proud of his son’s development: “He respects the game and knows it’s a business. He’s passionate about baseball.”39

Rivera is a strong advocate of education and acknowledged the hardships of baseball, especially for Puerto Ricans typically signed out of high school. He stated, “Education and discipline go hand in hand. The danger is that, if baseball does not work out and you don’t have a plan B … you may not wish to return to college. It may be really hard to go back, and you may be unable to make the most out of your ability and intelligence. Having goals … helps one overcome the tough times.”40

He credited his four decades in baseball as a testament to “being passionate, having (baseball) in the blood, and being responsible with my job, respecting my colleagues. … I thank God for opening so many doors. He’s given me everything and I just try to do the best I can when I am on the field and work hard.”41

A Little League park in his hometown was named in Rivera’s honor in 2015. In his self-deprecating way, he noted, “I don’t know if I deserve it, but it’s up to the local authorities, and they keep it in nice shape.”42

Last revised: February 14, 2024

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and David Bilmes and fact-checked by Ray Danner.

Sources

The author consulted baseball-reference.com, thebaseballcube.com, and beisbol101.com

Notes

1 The story is recounted by Rivera in the interview he gave with Emanuel González Castrodad for the Villapr YouTube channel, “Entrevista a Luis ‘Papa’ Rivera, primer cidreño en jugar MLB!,” April 29, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QbEWe03xLno (hereafter Rivera/Villapr interview).

2 Rivera/Villapr interview.

3 Eunice Castro Camacho, “Luis ‘Papa’ Rivera: Coach de Tercera, Azulejos de Toronto,” Periódico Cidra Somos Todos, Febrero 2019, https://issuu.com/josesantiago4/docs/boletin_febrero_2019_issuu

4 Eunice Castro Camacho, “Luis ‘Papa’ Rivera: Coach de Tercera, Azulejos de Toronto.”

5 Entrevista a Luis “Papa” Rivera, primer cidreño en jugar MLB!, Facebook, April 29, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QbEWe03xLno

6 Luis Rivera/Villapr interview.

7 1988 Topps Traded Luis Rivera Baseball Card (#94T), https://www.tcdb.com/ViewCard.cfm/sid/126/cid/54744/1988-Topps-Traded-94T-Luis-Rivera

8 “San Jose Expos,” Fun While It Lasted, https://funwhileitlasted.net/2019/08/02/1982-san-jose-expos/

9 Montreal Expos 1987 Prospects List, The Baseball Cube, https://www.thebaseballcube.com/content/player/17186/prospects/

10 Rivera/Villapr interview.

11 Rivera/Villapr interview.

12 Eunice Castro Camacho, “De diamante la trayectoria de Luis ‘Papa’ Rivera,” Periódico Visión, July 2014, https://issuu.com/josesantiago4/docs/boletin_febrero_2019_issuu

13 Peter Pascarelli, “N.L. Beat: Dealing Smith Showed Frey Willing to Gamble,” The Sporting News, December 21, 1987: 48.

14 “Baseball: N.L. East,” The Sporting News, January 25, 1988: 52.

15 “Rivea Had Short Stop; He’ll Stick,” The Sun-Sentinel, February 29, 1988

16 “Nuestro PR Luis “Papa” Rivera Opening Day (1988) vs. Dwight Gooden,” Me Gustan los Deportes, March 25, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uxFh4WuBYZU

17 Joe Giuliotti, “Rivera Proving to Be Steal for Sox,” The Sporting News, August 28, 1989: 21.

18 Joe Giuliotti, “Rivera Proving to Be Steal for Sox.”

19 Joe Giuliotti, “Rivera Proving to Be Steal for Sox.”

20 Entrevista, Facebook.

21 Jack Clark actually did not join the Red Sox until 1991.

22 Joe Giuliotti, “Baseball: A.L. East,” The Sporting News, July 1, 1991:18.

23 Joe Giuliotti, “Baseball: A.L. East,” The Sporting News, July 8, 1991:18.

24 Giuliotti, “Baseball: A.L. East,” The Sporting News, July 1, 1991:18.

25 Eunice Camacho Castro, “De diamante la trayectoria de Luis ‘Papa’ Rivera.”

26 Rivera/Villapr interview.

27 Jay Floyd, “1BJW Talks with Fishercats Manager Luis Rivera,” September 8, 2010, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fJcvybtyHmU

28 John Lott, “A Spy Lurks Among the Blue Jays,” National Post, May 24, 2011, https://nationalpost.com/sports/mlb/a-spy-lurks-among-the-blue-jays

29 John Lott.

30 John Lott, “Blue Jays’ Luis Rivera Will Use Exhibition Games to Sharpen Third-Base Coaching Skills,” National Post, February 22, 2013, https://nationalpost.com/sports/baseball/mlb/blue-jays-luis-rivera-will-use-exhibition-games-to-sharpen-third-base-coaching-skills

31 Rivera/Villapr interview.

32 Edgar Valencia interview with Luis Rivera, Losazulejos.ca, 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EzoaGKcMY_c

33 Edgar Valencia interview.

34 “Luis ‘Papa’ Rivera coach de tercera base de PR,” Periódico Visión, November 9, 2022, https://www.periodicovision.com/luis-papa-rivera-coach-de-tercera-base-de-pr/

35 Robet Rizzo, “Latino Managers in Major League Baseball,” ESPN, November 24, 2023, https://www.latinosports.com/latino-managers-in-major-league-baseball/#:~:text=Out%20of%20the%2030%20managers,Oliver%20Marmol%20of%20the%20St. This biography was written in December 2023.

36 Brendan Kennedy, “Where Have All the Latino Managers Gone?,” Toronto Star, May 24, 2016, https://www.pressreader.com/canada/toronto-star/20160524/282278139571092

37 Brendan Kennedy.

38 David S. Glasier, “Yan Rivera Following In Father’s Footsteps on Captains’ Staff,” News-Herald, July 1, 2022, https://www.news-herald.com/2022/07/01/852442/

39 David S. Glasier.

40 Eunice Camacho Castro, “De diamante la trayectoria de Luis ‘Papa’ Rivera.”

41 Rivera/Villapr interview.

42 Rivera/Villapr interview.

Full Name

Luis Antonio Rivera Pedraza

Born

January 3, 1964 at Cidra, (P.R.)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.