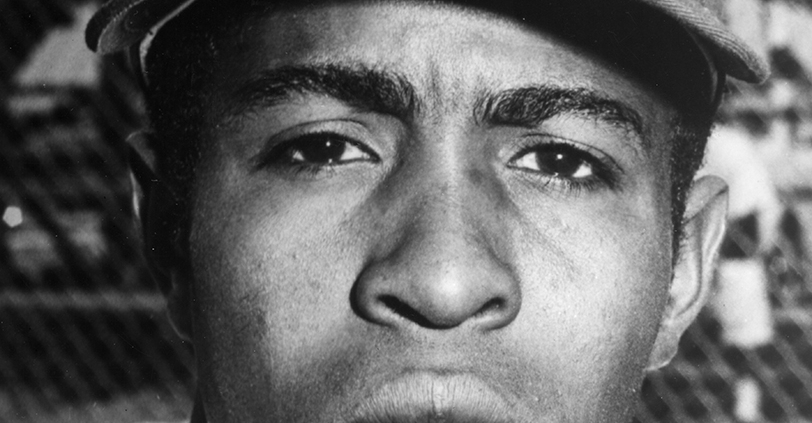

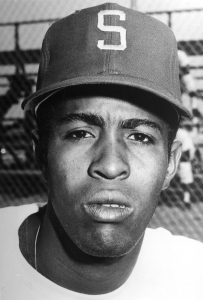

Miguel Fuentes

What if? Are there any more tragic words in the English language?

What if? Are there any more tragic words in the English language?

Helen of Troy’s face is reputed to have launched a thousand ships. Miguel Fuentes’ story may have launched fewer conversations, but the former is a myth while the latter is reality. Or in Shakespearean terms, a tragedy.

For the Seattle Pilots’ fans, whose team was seized by a literal used-car salesman and later commissioner of baseball – Bud Selig – the what-if questions are endless. What if Sick’s Stadium had been adequately prepared before the 1969 season, as promised by the city? What if William Daley, who owned more of the club than anyone else, had been willing to provide more financing? What if the other American League owners had not been nervous about the Pilots’ misfortunes putting their own investments in peril?

As those quandaries were being considered, a promising 23-year-old pitcher, seemingly at the cusp of living up to his potential, lay dying in a dark alley in Loíza, Puerto Rico, on January 29, 1970. The Seattle press was not immediately aware of the importance of his demise, though his death presaged the end of major-league baseball in Seattle until the arrival of the Mariners in 1977.

Not much is recorded about Miguel’s youth. He was born in Loíza, a town to the east of San Juan, on May 10, 1946. Only two Puerto Ricans, Hiram Bithorn and Luis Rodríguez Olmo, had played in the major leagues by then. Their Caucasian features enabled them to bypass the “unofficial” color rule, which was broken by Jackie Robinson barely a year after Fuentes was born.

Fuentes’ father, Miguel Fuentes Ortiz, was previously married before exchanging vows with Nery Pinet Pizarro. As a youth, the baseball-mad Miguel Jr. attended Jesusa Vizcarrondo Middle School, though it is unclear whether he graduated from high school. At 18, he starred with the Río Piedras Cardenales (Cardinals) under skipper Ramón “Monche” Román. Two years later, his contract was transferred to Río Grande, a town next to Loíza; he led the Guerrilleros (Warriors) to the national title, defeating the Aibonito Polluelos (Chicks) 7-1 on September 8, 1968. His personal statistics (17-12, 236⅓ innings, 192 strikeouts, 2.70 ERA) were among the league’s best.

Former Negro League player Félix “Felle” Delgado, who once hit a home run against Satchel Paige in the Puerto Rican Winter League, noticed the youngster. Although Delgado played only one season for the New York Cubans, he wore the San Juan Senators uniform for 27 years as a player and three more as a manager. He scouted for the Kansas City Monarchs and later became the Latin American supervisor for the Seattle Pilots/Milwaukee Brewers franchise, signing 31 players who reached the majors, with Fuentes being the first.1

More than 2,000 miles separate Iowa from Puerto Rico, but as the spring of 1969 began, five islanders were on the Clinton Pilots roster. Outfielder Domingo Apellaniz did not advance beyond Double A. Infielders Pedro García and Fernando González would appear in hundreds of major-league games. Carlos Velázquez, himself also a pitcher from Loíza, lasted only one season in the majors. But it was Fuentes who reached the promised land first, even if his stay was all too brief. The club, previously a Pirates affiliate, won 72 games against 51 defeats, good for second place in the circuit behind the Appleton Foxes, who were declared the champions after winning both halves of the season.

Fuentes produced superb numbers, including a 1.46 ERA in 74 innings pitched. He was careful to keep the ball within the ballpark, as evidenced by his two home runs allowed, and was stingy with walks (22, against 62 strikeouts). The team employed a dozen other hurlers as starters, wanting to give everyone a chance to display his talents. Half of Fuentes’ six starts were complete games, two of them shutouts. Overall, his 8-2 mark, along with two saves, was enabled by a .932 WHIP, the best in the league (minimum 25 innings pitched). The Cedar Rapids Gazette noted that “Fuentes, the winner, stopped the Cards without a hit in the last three innings” during the Pilots’ June 16 win over the Cedar Rapids Cardinals.2 On July 5, 1969, as the Angels affiliate swept a doubleheader from the Pilots, the Quad City Times noted, “Miguel Fuentes pitched the last four innings for the Pilots, giving only two hits and an unearned run.”3

The Pilots called up the promising young hurler to the majors when rosters expanded in September. Fuentes was given uniform number 14, the third Pilot to don it. (Jim Gosger had earlier been traded to the Mets while Gordy Lund returned to the minors after a swap with the Angels.) He was thrust into service on September 1 at Yankee Stadium, tossing a scoreless ninth inning with two strikeouts and a groundout. The Pilots, however, lost, 6-1. His second appearance was five days later, again closing the game in another Seattle loss, this time against their expansion siblings the Kansas City Royals. Fuentes faced the minimum as a batter he walked was caught stealing.

Satisfied by the right-hander’s performance, the Pilots handed him the ball on September 8 against the White Sox. The clubs played a day-night doubleheader and the Pilots won the first contest, 2-1. Seattle fans were treated to his home debut, and Fuentes did not disappoint. A crowd of 10,831 witnessed three first-inning Pilot runs, the only run support he would need. The White Sox, ahead of only Seattle in the American League Western Division standings, were far from a dangerous team, finishing in the bottom third of the league’s offensive categories, but Fuentes showed remarkable poise while facing, for the first time, an entire lineup of big leaguers. Fuentes handcuffed Chicago until the eighth inning, when Angel Bravo tripled to lead off the frame and scored on a single by Walt Williams. Fuentes helped himself at the plate, delivering a single, advancing to third on a wild pitch and groundout, and scoring a run. He went the distance, allowing only Bravo’s run, seven hits, and two walks for his only major-league win.

The United Press noted “slender Miguel Fuentes pitched a seven-hitter in his first major-league start…Fuentes was in complete control.”4 Chicago manager Don Gutteridge reckoned, “It’s too early to know for sure, but it looks like that youngster is going to be one fine pitcher. He had lots of poise and was throwing good stuff.”5

Five days later Fuentes faced the Angels. He yielded a first-inning run, retired the side in order in the next two innings, and allowed a single in the fourth. The fifth inning began with promise as he induced a fly out and a pop fly before he walked Sandy Alomar Sr. His countryman ran wild on the bases, stealing second and third before scoring on a triple by Jim Spencer. The next frame brought another run across the plate as Aurelio Rodríguez drove in Bill Voss, prompting Pilots manager Joe Schultz to lift Fuentes with one out. His opponent, Eddie Fisher, kept the Pilots scoreless through eight-plus innings for the 4-2 victory.

The White Sox figured out the right-hander and their next meeting, on September 17, was rough for the pitcher. Marty Pattin opened for Seattle and allowed three runs in five innings; Fuentes, in relief, faced nine batters and retired four, allowing four hits, a walk, and three runs. California may have also studied their scouting reports and they reached Fuentes for five runs in 5⅔ frames, tagging him with his second loss on September 23. His final start of the season was against Minnesota on September 28 and he quickly ran into trouble, yielding a leadoff home run to Ted Uhlaender. Two more runs crossed the plate in the second inning before Fuentes was lifted for John O’Donoghue. The loss dropped his register to 1-3 and swelled his ERA to 5.40.

The Pilots’ lone regular season in Seattle ended on October 2, 1969, in front of 5,473 fans. Starter Steve Barber allowed three runs (two earned) in two innings; subsequent relievers kept Oakland scoreless. The Pilots could muster only one run against Jim Roland and fell, 3-1. Taking the mound in the ninth inning, Fuentes retired Phil Roof via groundout and struck out Roland. Bert Campaneris singled and stole second. With a runner in scoring position, Fuentes walked Danny Cater before inducing Reggie Jackson to line out to center field. The ledger showed no runs, one hit, no errors, and two men stranded on base, but a lot more was left on the field of Sick’s Stadium. The crowd had unknowingly witnessed the last pitch not just in Pilots history but also of Fuentes’ big-league career.

A few months later, after the end of the semifinals of the Puerto Rican Winter League, Fuentes went to a bar in his hometown. A plumbing issue rendered the bathroom unusable, prompting a trip outside to relieve himself. Another patron, perhaps believing Fuentes was purposely urinating on his car, shot him three times, in the right hand, left thigh, and abdomen. Although Fuentes received medical care at a nearby hospital, his body had gone into shock and the doctors could not save his life during the surgery. The police detained a suspect, but he was not charged with a crime. In a bittersweet twist, Fuentes’ brief major-league career is captured in only one baseball card, number 88 in the 1970 Topps set. He shares the honor with Dick Baney, under the optimistic title “Pilots Rookie Stars.” Baney would later fondly recall him as the “nicest kid you’ll ever meet.”6

Despite its rich baseball tradition and hundreds of major leaguers, Puerto Rico has not produced many high-caliber hurlers. Javier Vázquez, with a 3:1 strikeout-to-walk ratio and 165 victories, is arguably the first face on Mount Rushmore. Juan Pizarro, who tossed 17 shutouts during his 18 years (both highs among natives), can claim second place. Jaime Navarro and Joel Piñeiro, the only others to reach triple-digit victories; Willie Hernández, the 1984 American League MVP and Cy Young Award winner; Luis Arroyo, All-Star Yankees closer for the 1961 World Series team; and Roberto Hernández, 19th on the all-time save list, can argue for the other two spots.7 (Brooklyn-born John Candelaria, whose parents were born on the island, earned 177 big-league wins.)

Would Fuentes have reached such heights? It’s hard to tell. His professional baseball career was very short. Perhaps the best comparison is Juan Nieves, whose career was cut short by an arm injury at the tender age of 23. Nieves’ 94 games in the majors included not just 32 victories but also the only (as of 2022) no-hitter tossed by a Puerto Rican-born pitcher, also the first no-hitter in Milwaukee Brewers history.8 Rangers prospect Ed Correa, who led 1986 rookies with 189 strikeouts at 20 years old, serves as a fair comparison, as his career-ending injury in 1987 produced eerie similarities.

Fuentes’ story is far from rare among Puerto Rican players. Bithorn, the first native to play in the major leagues, was killed by a police officer under mysterious and controversial circumstances while playing in Mexico in 1952. Luis “Canena” Márquez, the third islander to reach the majors, was murdered by his son-in-law in 1988. The perpetrator was never convicted of the crime. In 2003 Iván Calderón, a one-time All-Star with the Montréal Expos who spent a decade in the big leagues, was also murdered in Loíza, a victim of rival gangs and his own willingness to lend money to people involved in underground betting.

Sadly, younger generations of Puerto Ricans are unaware of Fuentes’ legacy. Ironically, Hurricane María, which devastated the island in 2017, may have broadened the scope of his story. Miguel Fuentes Pinet Stadium, home to the Double-A Cocoteros de Loíza, was severely damaged. As residents seized the opportunity to rebuild, its walls were decorated by defiant silhouettes of Afro-Puerto Rican pride. The murals captured the fighting spirt of the northeastern town, long celebrated as the birthplace of bomba music. African traditions remain strong in the town, with vejigante festivals, where local artisans craft elaborate masks from coconut husks, adorn storefronts. Among those works of art adorning the field, only one depicts an athlete. Against a backdrop of red, much like the three crimson stripes of the Puerto Rican flag, is the visage of Fuentes, composed of mostly gray and white mosaics with a cap showcasing his hometown “L.” The hundreds of pieces aptly represent the shattered potential taken by the assassin. The work, titled “Between Dreams Achieved and Dreams Still to Be Achieved,” by local artisan Celso González and the Monument Art initiative, proves that the eternal promise of Fuentes has not been forgotten by its hometown.9

The Milwaukee Brewers did not enjoy a winning season until 1978, when they began a streak of six consecutive years above .500, marked by the 1982 American League pennant. The franchise has been unable to develop strong pitching; its WAR leader, Teddy Higuera (30.3, 1985-1991, 1993-1994) was a one-time All-Star eclipsed by contemporaries like Roger Clemens, Dave Stewart, Dave Stieb, and Bret Saberhagen. The mediocre early 1970s Brewers may have been helped by a developing Fuentes, though his trajectory was far from guaranteed. A team official, lamenting his death, noted that “he was extremely poised” despite his youth.10 Another news report confirmed that the Pilots had added Fuentes to the 40-man roster, remarking, “[H]e was a fine prospect with a major-league arm. … [A]all he needed was the experience so he could learn how to pitch.”11

Fuentes’ star may have shined brightly in the otherwise dark skies of 1970s Brewers baseball. His dominant performance in the Midwest League augured a promising future. Perhaps if he had been called up to the big leagues earlier, his story might have had a different ending. None of the eight pitchers who started 10 or more games for the 1969 Pilots enjoyed a winning record; only John Gelnar had an ERA below 4.00. Clearly the club needed the pitching Fuentes could have provided. Had his workload gone beyond the 26 innings tossed in September, would the franchise had allowed him to pitch in the Puerto Rico Winter League? Back in the 1960s and 1970s, the circuit was a breeding ground for young talent who sought to prove their worth against established big leaguers, so his workload might have not been restricted.

Fuentes remains forever entrenched in Pilots lore not just for that magical September night, but also for throwing the last pitch of the franchise’s stay in Seattle on October 2, 1969, before its sudden move to Milwaukee in the spring of 1970 after being purchased by future Commissioner Selig. Much like the Pilots, Fuentes represents what could have been.

Acknowledgments

The Loíza Cocoteros for providing details on Miguel Fuentes (accessible via https://www.loizacocoteros.com/miguelfuentespinet).

Héctor “Titito” Rosa for providing information about Miguel Fuentes’ youth and amateur career.

Retrosheet.org and Baseball-reference.com for Fuentes’s statistics and game logs.

Photo credit: Miguel Fuentes, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Notes

1 Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, eMuseum Electronic Resources for Teachers, Profile on Félix Delgado, https://nlbemuseum.com/history/players/delgado.html.

2 Gus Schrader, “C.R. Cards Lose, End Home Stay,” Cedar Rapids (Iowa) Gazette, June 16, 1969: 15

3 Jerry Jurgens, “Riggins Sets Off Fireworks as Q-C Angels Sweep,” Quad City Times (Davenport, Iowa), July 5, 1969: 13.

4 United Press, “Pilots Deal Two Defeats to White Sox.” Washington Post, September 9, 1969: D2.

5 Associated Press, “Seattle Battles for Cellar Spot in West,” Albany (Oregon) Democrat Herald, September 9, 1969: 11.

6 Larry Stone, “Greg Halman’s Death Reminds of Other Major Leaguers Killed,” Seattle Times, November 22, 2011, https://www.seattletimes.com/sports/mariners/greg-halmans-death-reminds-of-other-major-leaguers-killed/.

7 Hernández and his 326 saves ranked 19th in the all-time list as of the conclusion of the 2022 season.

8 Nieves’s no-hitter was also the only one in the Brewer franchise history through 2021, when Corbin Burnes and Josh Hader combined to no-hit the Cleveland Indians on September 11.

9 The mural can be seen on this Website: https://repeatingislands.com/2020/09/03/explore-local-puerto-rican-art-in-this-urban-route/. It is a reproduction of the Fuentes image used in the 1983 Renatta Galasso trading card set of the 1969 Seattle Pilots (https://www.tcdb.com/ViewSet.cfm/sid/80771/1983-Galasso-1969-Seattle-Pilots).

10 Associated Press, “Young Pilot Pitcher Is Shot, Dies,” Johnson City (Tennessee) Press-Chronicle, January 30, 1970: 39.

11 United Press International, “Pilot Rookie Dies After Bar Shooting,” Honolulu Advertiser, January 30, 1970: 34.

Full Name

Miguel Fuentes Pinet

Born

May 10, 1946 at Loiza Aldea, (P.R.)

Died

January 29, 1970 at Loiza Aldea, (P.R.)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.