Todd Cruz

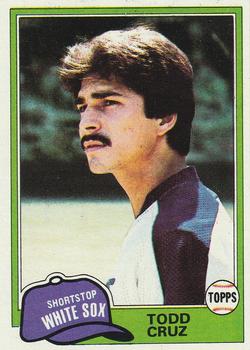

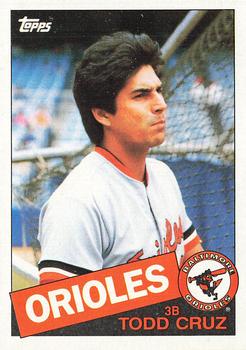

Todd Cruz spent parts of six seasons from 1978 to 1984 as a rifle-armed infielder for six teams. Originally a shortstop, he made two Opening Day starts at that position for the Mariners. After the Orioles converted him to third base, Cruz played every post-season game there for Baltimore’s 1983 World Series champions.

Todd Cruz spent parts of six seasons from 1978 to 1984 as a rifle-armed infielder for six teams. Originally a shortstop, he made two Opening Day starts at that position for the Mariners. After the Orioles converted him to third base, Cruz played every post-season game there for Baltimore’s 1983 World Series champions.

Todd Ruben Cruz was born on November 23, 1955, in Highland Park, Michigan. He grew up in southwest Detroit’s Mexicantown neighborhood, not far from Tiger Stadium. According to Todd, his father, Robert Cruz, spent a couple years in the Tigers’ farm system in the early 1950s.1 In 1951, Robert married Marie (Gruffner), from Windsor, Ontario. Robert’s roots were Mexican, Marie’s Hungarian; their daughter Sharon arrived the following year. “[Todd’s] mom and dad both had drinking problems,” recalled Ignacio “Uncle Zig” Gonzalez, the father of Cruz’s childhood friend, David. “When Todd was six, his mom and dad separated. Todd lived with his mom, sometimes with his dad … they seemed to move every nine or 10 months.”2

Cruz’s amateur baseball experience included Police League and Boys Club of America teams, another sponsored by Kowalski Sausage, and the Romanowski and Honeybees entries in the Detroit Amateur Baseball Federation. He named hitting for the cycle as a member of the Honeybees as one of his most exciting moments.3 At Western High School, Todd won a league batting title and led the Cowboys to a championship.4 The 6-foot, 175-pounder also played football and basketball.5 After Cruz’s senior-year homeroom teacher, Uncle Zig, noticed him showing up late and exhausted, he discovered that Todd was shining shoes at the Michigan Central Depot train station at night to earn money to help his mother.6

In June 1973, Cruz graduated, was voted to UPI’s All-State Baseball team by area coaches, and was picked by the Phillies in the second round (26th overall) of the Amateur Draft.7 The Philadelphia Daily News noted that the talent pool was “heavy with infield prospects.” Robin Yount, Johnnie LeMaster and Pat Rockett were big-league bound shortstops selected ahead of him.8 After signing with scout Tony Lucadello, Cruz reported to the Rookie-level Appalachian League.9 In 69 games with the Pulaski (VA) Phillies, the 17-year-old struck out 76 times, batted .183 and committed 49 errors.

He made 51 more miscues in 1974. Other than four games with the Toledo Mud Hens at the end of the Triple-A International League season, Cruz spent the year with the Single-A Rocky Mount (NC) Phillies, batting .193 in 126 contests with a lone home run. He also went deep on July 11 for the Carolina League All-Stars.10 That winter, Cruz married his high school girlfriend, Isabel Cantú González. They would have two sons, Thaddeus and Dario.

Back at Rocky Mount in 1975, Cruz’s bat began showing life. On April 20, he hit a grand slam and a three-run homer against Winston-Salem.11 After collecting 33 RBIs, 10 doubles and six homers in May, he was named Topps’s Carolina League player of the month.12 Despite fading to finish with 11 homers and a .203 batting average in 134 games, Cruz earned another All-Star selection by fielding a league-best 716 chances and reducing his error total to 41. Rocky Mount romped to the championship and the Phillies added him to the 40-man roster.

In 1976, Cruz advanced to the Double-A Eastern League and raised his average to .231 with the Reading (PA) Phillies. In 123 contests, he committed 53 errors, but the circuit’s managers voted him the best shortstop.13 Phillies farm director Dallas Green didn’t necessarily agree. After visiting the underachieving, 54-82 Reading club, Green named Cruz the team’s most disappointing player.14

According to Pittsburgh-Post Gazette writer Gene Collier, in the late 1970s Cruz “had a talent for hitting his head on the rear-view mirror of his car in auto accidents, [i.e.] he gets punched in the face a lot’.”15 Phillies GM Paul Owens acknowledged, “[Cruz] was a real hard-nosed kid when he came in, from growing up in Detroit. We had to slow him down a bit from popping off.”16 Cruz returned to Reading in 1977, made another 50 errors and saw his batting average decline to .216 in 131 games. He took a big step forward in the Venezuelan Winter League, batting .316 with a club-best 16 doubles in 46 regular-season contests to help the Águilas del Zulia reach the finals.17 “I wanted to go there. The game down there was fun for me,” Cruz said.18 He returned to Zulia for five more seasons.

The Phillies promoted him to the Oklahoma City 89ers in the Triple-A American Association in 1978, but Cruz went 0-for-28 on the first home stand. “I think Todd has the Triple-A jitters,” remarked 89ers manager Mike Ryan.19 Cruz came back to bat .261 in 121 contests, his best full-season mark as a pro. On September 4, he made his major league debut, replacing Larry Bowa at shortstop for the final inning of a 10-2 Phillies victory in St. Louis. Cruz fielded Dane Iorg’s grounder and threw to second baseman Bud Harrelson for the final out. The Phillies were closing in on a third straight division title, however, and Bowa –an All-Star and Gold Glove winner–was determined to play. “Larry didn’t want to come out of any game for any inning at any time,” Cruz recalled. “I guess I understand it now, but it was a tough thing to face.”20 Other than one pinch-running appearance, Cruz didn’t play again until the Phillies clinched. He started the regular-season finale in Pittsburgh and singled off Pirates’ righty Odell Jones in his first atbat. He was thrown out by catcher Steve Nicosia when he tried to steal second but stroked a two-run single later and finished the contest 2-for-4.

Next, Cruz helped Zulia return to the Venezuelan finals, batting .284 with a team-leading 41 RBIs in 66 games. Orioles scout Jim Russo said, “The guy was doing it all: hitting the ball all over the place and fielding like a sonuvagun, making spectacular plays.”21 Cruz was out of options in 1979, so the Phillies had a decision to make. “We’ve all watched his growing up stages. He looks like he’s finally ready and there’s no room for him,” lamented Green.22 On April 3, three days before Opening Day, Cruz was traded to the Royals for veteran reliever Doug Bird.

Cruz returned to the American Association and collected 13 extra-base hits and 21 RBIs in 21 games for the Omaha Royals to begin the year. Seven of his hits were home runs, including a game-winner against Springfield on April 30. Afterwards, he declined to speak to the press. “He said he’s a little backward about talking to people,” explained Omaha manager Gordy MacKenzie.”23 On May 9, Kansas City called Cruz up to the majors. For three-and-a-half months, Cruz shared shortstop starts with a 34-year-old former All-Star. “They told me Freddie Patek was on the way out,” he recalled.24 On May 27, Cruz belted his first big-league homer, an eighth-inning shot off Jerry Koosman in Minnesota to win a game, 2-1. In 55 games, he batted .203. In late-August, the Royals tried U L Washington at shortstop and the speedy switch-hitter held the job for nearly five years. Cruz, outfielder Al Cowens and a player to be named later (Craig Eaton) were traded to the California Angels at the winter meetings for slugging first baseman Willie Aikens and infielder Rance Mulliniks.

Cruz made California’s Opening Day roster, but the Angels had signed free agent Patek to start with 38-year-old Bert Campaneris in reserve. “We got Cruz more as third base insurance for Carney Lansford than we did to play short,” explained GM Buzzie Bavasi. Cruz appeared in only 18 of California’s first 53 games, hitting .275 but committing eight errors at three infield positions. Russo, the scout he’d impressed in Venezuela two winters ago, observed, “This kid looked like he was lost. He was kicking the ball all over the place. You’d look at him on the field and you’d swear the guy was praying for each batter NOT to hit the ball to him.”25

When Cruz was dealt to the White Sox for reliever Randy Scarbery on June 12, he joined his fourth organization in less than two years. Chicago manager Tony La Russa insisted, “The only thing that can cost him a job is if he starts hitting .160, and I don’t think [hitting instructor] Orlando Cepeda will let that happen.”26 An Angels official told the Chicago Tribune that Cruz’s glove work might prove more problematic. “Cruz’s problem has been that he slaps at the ball when he fields it, resulting in fumbles. Maybe somebody on the Sox can cure the habit.”27

“Catching the ball two-handed is something I have to do, but it’s unnatural to me,” Cruz confessed. Chicago coach Bobby Winkles, a former infielder, said, “We’re making a complete change in a young ballplayer in the major leagues.” Though Cruz committed 20 errors in 90 games after the trade, a 21-game September stretch with a single miscue was encouraging, and his .232 batting average wasn’t disqualifying. “I think he convinced a lot of people that the White Sox don’t have to look for a shortstop,” Winkles said.28

Cruz’s arm was voted the strongest among American League infielders in The Sporting News’ 1981 spring training poll.29 “To be the shortstop on Opening Day, that is my dream,” he said. Six days before the season, however, he injured his back swinging during an exhibition game. Cruz tried to come back too soon and was shut down when the pain worsened.30 Meanwhile his replacement, Bill Almon, was batting over .300 and Cruz’s marriage was heading for divorce.31 When he finally hit his first home run of the season on May 18, it was for the Edmonton Trappers in the Triple-A Pacific Coast League. That night, he had three or four beers at a lounge with teammates Fran Mullins and Marv Foley before they left him around 11 p.m. Cruz stayed until closing time.32 “I had a few drinks and was thinking of things, and I let things get to me,” he recalled.33

Cruz smashed the plate glass window of a Hudson’s Bay store, broke into a display case, put four wristwatches on each of his arms and fell asleep.34 He also set off a burglar alarm, so a guard dog found him dozing around 4 a.m.35 He was arrested and charged with breaking and entering, and spent 30 hours in jail before he was released on $1,500 bond.36 He returned to the store to apologize and promise restitution.37 “I’m sorry it happened, but I can’t change it,” Cruz said.38 He faced up to 14 years in prison, but an Edmonton judge sentenced him to the equivalent of nine months’ probation on July 14.39 He returned to action with Edmonton but broke a bone in his left hand almost immediately.40 In a lost season, Cruz played only eight games for the Trappers but healed in time for winter ball. On December 11, the White Sox traded him to the Mariners along with catcher Jim Essian and outfielder Rod Allen for outfielder Tom Paciorek.

In 1982, Cruz started 136 games at shortstop for Seattle, including Opening Day. Players jokingly offered him the watches they received for post-game interviews. “On one team flight, I got all the guys to give me their watches, and I put them in a box and gave them to Todd. I said, ‘Here watch these for us’,” recalled Mariners manager Rene Lachemann. “I wanted to show him we had faith in him, that yesterday didn’t mean anything.”41 Cruz’s glove work was a key reason that Seattle stayed over .500 into August and finished fourth for the first time. “We can afford to lose him less than anybody else,” insisted Lachemann. “He’s been outstanding. He’s saved us 50 hits already with his defense.”42 Cruz participated in more double plays than any AL shortstop that season, often in acrobatic fashion with second baseman Julio Cruz (no relation). “You can’t practice the exceptional double play,” Todd said. “It’s instinct.”43

Cruz also hit 16 home runs to establish a record for Mariners’ shortstops that lasted until Alex Rodriguez ripped 36 in 1996. On April 25, He capped his only career 4-for-4 performance with a walk-off blast against the Twins’ Terry Felton. He went deep during both of Seattle’s visits to Detroit and smacked a grand slam on August 17 in Minnesota. His biggest weakness was his plate discipline: his 95:12 strikeout-to-walk ratio resulted in a feeble .246 on-base percentage. “I know I swing too hard, but I don’t feel good if I swing too easy and ground out,” he said.44

In 1983, Cruz hit .298 in April, including two homers in a game against the Yankees. By the last week of June, however, his average was .190, Seattle had the worst record in the majors and Julio Cruz had been traded to the White Sox. “It was terrible. It was depressing,” Todd said. “All the changes out there, all the losing, I started to lose my enthusiasm.”45 He soon lost his job as well. On June 25, Seattle called up 1982 first-round draft pick Spike Owen to play shortstop, axed Lachemann, and released Cruz and 44-year-old pitcher Gaylord Perry. “I didn’t worry. I thought they were stupid,” Cruz recalled. “I’d already been with five teams; you get used to it.”46 He went home and played with his sons in his backyard.

On June 30, the Mariners called to tell him that the Orioles had acquired him for an undisclosed sum. Later, he’d call it “the best thing to happen to me in baseball.” Cruz told the Baltimore Sun, “It was like I was still dreaming because everyone wants to play here.”47 The next day, the Orioles opened a series in Detroit. While Baltimore’s Cal Ripken was enjoying an MVP campaign in his first full season at shortstop, manager Joe Altobelli desperately needed a third baseman to replace demoted rookie Leo Hernández. Though Cruz had only started eight games at the hot corner as a pro, he said, “I’m willing to play wherever they want me, I mean, it’s not like I’ll play third base like I don’t know what I’m doing.”48

Cruz’s debut in front of 40,493 on a Friday night at Tiger Stadium was a smashing success. Baltimore and Detroit were tied for second place, two games behind Toronto. In the top of the third, the Orioles trailed by a run with two outs when Tigers manager Sparky Anderson ordered Jim Dwyer to be intentionally walked to load the bases for Cruz –who delivered a three-run double. Two innings later, when Anderson had Dwyer walked again with two outs, Cruz clobbered a three-run homer to knock pitcher Milt Wilcox out of the game. Cruz’s career-high six-RBI performance keyed Baltimore’s 9-5 victory, and he called it one of his greatest career thrills.49

Cruz’s debut in front of 40,493 on a Friday night at Tiger Stadium was a smashing success. Baltimore and Detroit were tied for second place, two games behind Toronto. In the top of the third, the Orioles trailed by a run with two outs when Tigers manager Sparky Anderson ordered Jim Dwyer to be intentionally walked to load the bases for Cruz –who delivered a three-run double. Two innings later, when Anderson had Dwyer walked again with two outs, Cruz clobbered a three-run homer to knock pitcher Milt Wilcox out of the game. Cruz’s career-high six-RBI performance keyed Baltimore’s 9-5 victory, and he called it one of his greatest career thrills.49

Cruz appeared in 81 games for the Orioles and started 65, including all eight during a winning streak that lifted the team into first place to stay in late August. “Todd was the perfect piece for our team,” Altobelli observed. “Boy, oh boy, did he fit our infield.” Outfielder Gary Roenicke recalled, “[Cruz] had an outgoing personality, he talked real fast and he kept everybody loose, on and off the field.”50 Baltimore finished 98-64 with a lineup that often featured what teammate Ken Singleton playfully called the “Three Stooges” at the bottom of the batting order. Catcher Rick Dempsey, a .231 hitter with four homers, was “Moe.” Second-baseman Rich Dauer (.235 with five home runs) was “Larry.”51 “Call me Curly. He was always my favorite,” said Cruz, who batted .208 with three homers. “You know how Curly can hop backward? I can do that.”52

In October, Cruz started all nine of Baltimore’s playoff games. In Game Two of the World Series against the Phillies, he bunted for a fifth-inning single between Dauer’s base-hit and a double by Dempsey as the Three Stooges keyed the Orioles’ winning rally. Following Baltimore’s one-run win in Game Three, Cruz nearly got into a bar fight in Philadelphia.53 When the Orioles finished off the Phillies two days later, he made a nice play going to his left to start an around-the-horn double play. Cruz batted only .129 in 31 post-season at bats, but he was a World Series champion.

That fall, Cruz reported to the Florida Instructional League to work with hitting instructor Ralph Rowe, who’d been reluctant to have him make major adjustments during the season. “He held the bat over his head with his hands high and wiggled the bat a lot,” Rowe described. “We’ve lowered his hands to his side, the bat is upright and he’s hitting down on the ball.”54 On December 8, Baltimore traded reliever Tim Stoddard to Oakland for Wayne Gross, a powerful, lefty-hitting third baseman.

Upon joining the Orioles, Cruz had addressed rumors that he’d often been late in Seattle. He confessed to having difficulty making early-morning spring training practices on time but insisted his lone in-season incident had been blown out of proportion. “I had no enemies. I don’t cause trouble and I don’t like to be controversial,” he said. “Sometimes you just get labelled.”55 A month after joining the Orioles, he overslept and missed the Hall of Fame game exhibition in Cooperstown.56 In 1984, he showed up with a spring training contest already in progress after falling asleep in the passenger seat while his driver went to the wrong city. He missed the workout on the eve of the season opener altogether.57

Nevertheless, Cruz was in uniform on Opening Day, shaking hands with President Ronald Reagan.58 While Gross recuperated from a strained knee ligament in April, Cruz was Baltimore’s primary third baseman, but he played less frequently as the season progressed; starting his final game on July 30 and batting only 34 times after the All-Star break. Most of his 96 appearances came as a late-inning defensive replacement. On August 25 in Oakland, he failed to show up for a game and didn’t call in sick until the seventh inning.59

Cruz had toyed around with pitching in 1980 with the Angels. California coach Deron Johnson recalled, “The catcher couldn’t catch him. I’ve never seen such an arm.”60 Late in the 1984 season, Cruz started throwing in Baltimore’s bullpen. “I’m taking it seriously. I’ll do anything to stay on the team,” he explained. “Rabbit [pitching coach Ray Miller] said I threw hard enough that I didn’t really need a breaking ball if I can learn a cut fastball. I can already make it sink.”61 On September 18, pitching in a game for the first time since he was 16, Cruz hurled a perfect inning in the Orioles’ 10-2 loss at Yankee Stadium.

In 1985, Cruz got off on the wrong foot by missing the Orioles’ first spring workout without calling anyone, reportedly because of personal problems with his separated wife. “I took his money, a day’s pay,” said Altobelli. “I told him to think about coming to the park and he might find someone able to help him.”62 “I’ve never been late on purpose, and I think they know that,” Cruz said. “It’s just that some people learn things the hard way, and I’ve always learned the hard way.”63 When Fritzie Connally –a big, righty-hitting third baseman– impressed in spring training, the Orioles decided to platoon him with Gross and release Cruz. His major league career ended with a .220 batting average and 34 home runs in 544 games.

Cruz wound up with Baltimore’s Triple-A Rochester Red Wings affiliate in May. He went 1-for-11 in five games before he was released again after arguing with manager Frank Verdi about being removed for a pinch hitter. “We’re a little disappointed,” said Orioles’ farm director Tom Giordano. “We gave Todd another opportunity to play. His agent called us. We did some things for Todd the public will never know about.”64

For the next three summers, Cruz played for unaffiliated Single-A clubs in Florida and California, then played in Leon. Mexico and Bologna, Italy. He described his offseason occupation as a drug and alcohol counselor.65 Just after his 35th birthday, he joined the St. Petersburg Pelicans for the second year of the Senior Professional Baseball Association. He was batting .313 in 21 games when the circuit folded. “The money was nice, and I could really use it,” Cruz said. “But most of all, playing in this league, playing baseball, was the thrill of a lifetime for most of us.”66 In 1991, Cruz returned to the California League as the Salinas Spurs’ shortstop. In the last 100 games of his professional career, he batted .254 with three home runs.

When the 1994 players’ strike remain unsettled during spring training 1995, major league owners hired prospective replacements. Cruz, then a 39-year-old grandfather, was one of the more recognizable names in the Philadelphia Phillies camp, but the labor dispute was settled. “I’m just happy to be getting the $5,000 [signing bonus],” Cruz said when he was cut. “It would have been nice to get the $20,000 [for making the Opening Day roster] because that’s about four times what I made last year, working in the batting cages…Still, no regrets. I had a great time.”67

For about a decade, Cruz lived with his girlfriend Cindy in Colton, California. In 2002, he helped start a league with the brother of former major league pitcher Oil Can Boyd geared towards helping overlooked young adult players gain exposure. “I would like to be a scout,” he said.68 In the fall of 2007, Todd and Cindy moved to a one-bedroom apartment in Bullhead City, Arizona, along the Colorado River, where his $22,000 annual major league pension could stretch further. At Buffalo Wild Wings, or the bar at the Edgewater across the river in Laughlin, Nevada, Cruz held court telling baseball stories. “Autographs were free, but a signed ball would cost a donation — whatever you could spare,” a reporter described.69

On July 23, 2008, Cruz attended the 25th reunion of the 1983 Orioles at Camden Yards. He was on crutches following back surgery, but said, “Being with these guys here is like being a little kid … getting ready for Christmas. I love them all, and I’ll be an Oriole for the rest of my life.”70

Six weeks later, on September 2, after his ride to a Diamondbacks-Cardinals game in Phoenix didn’t call, Cruz went swimming in the tiny pool at his apartment complex. His friends initially thought he was holding his breath underwater in the six-foot deep end, but they soon yanked him out of the water and attempted CPR. Paramedics arrived, but Cruz was declared dead at Western Arizona Regional Medical Center. He was 52. An autopsy diagnosed hypertensive cardiovascular disease as his cause of death, with cirrhosis of the liver due to chronic alcoholism as a contributing factor.71 His remains were cremated. “[Cruz] always wanted to talk baseball,” recalled bartender Chris Calahan. “He told me he wanted to coach Little League, that he wanted to be involved with baseball and kids, to show ’em how much fun it was.”72

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Gregory H. Wolf and Norman Macht and checked for accuracy by SABR’s fact-checking team.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted www.ancestry.com, www.baseball-reference.com and www.retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 Todd Cruz, Publicity Questionnaire for William J. Weiss, June 1, 1987.

2 Ron Kantowski, “Old Pro’s Story Ends Humbly in Desert Town,” Las Vegas Sun, September 18,2008: 1.

3 Todd Cruz, Publicity Questionnaire for William J. Weiss, August 27, 1973.

4 Cruz, Publicity Questionnaire (1973).

5 Cruz, Publicity Questionnaire (1987).

6 Kantowski, “Old Pro’s Story Ends Humbly in Desert Town.”

7 “1973 UPI All-State Baseball Teams Named,” Holland (Michigan) Evening Sentinel, June 16, 1973: 4.

8 “Phils Miss Chance at a Boonie and Clyde Battery,” Philadelphia Daily News, June 6, 1973: 87.

9 Cruz, Publicity Questionnaire (1973).

10 “Carolina Stars Soar on Fitzgerald’s Slam,” The Sporting News, July 27, 1974: 59.

11 “Five Homers, 13 RBI,” The Sporting News, May 20, 1975: 39.

12 “Four Repeat as Topps Toppers,” The Sporting News, June 28, 1975: 40.

13 1984 Baltimore Orioles Media Guide: 111.

14 “Phils Disappointment,” The Sporting News, August 28, 1976: 43.

15 Gene Collier, “Phillies’ Giles Taking His Swings,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, March 18, 1995: D1.

16 Paula Parrish, “Grandfather Cruz Seeks 2nd Chance,” Daily Journal (Millville, New Jersey), March 3, 1995: 20.

17 Venezuelan Statistics from http://www.pelotabinaria.com.ve/beisbol/mostrar.php?ID=cruztod001 (last accessed February 8, 2021).

18 Dave Nightingale, “Cruz Going Great — Can He Keep It Up?” Chicago Tribune, June 24, 1980: D1.

19 “American Assn.,” The Sporting News, June 3, 1978: 33.

20 Mark Whicker, “Cruz Hopes He’s Found a Home,” Philadelphia Daily News, October 13, 1983: 93.

21 Nightingale, “Cruz Going Great — Can He Keep It Up?”

22 Bill Conlin, “The Plight of Phils’ Talented Minor Leaguers,” Philadelphia Daily News, January 9, 1979: 55.

23 “Cruz Clubs Circuit Clouts,” The Sporting News, May 26, 1979: 50.

24 Robert Markus, “Bright Dream Only Painful Memory for Sox’s Cruz,” Chicago Tribune, May 5, 1981: C1.

25 Nightingale, “Cruz Going Great — Can He Keep It Up?”

26 Nightingale, “Cruz Going Great — Can He Keep It Up?”

27 Dave Nightingale, “Sox Trade Scarbery for Angels’ Shortstop,” Chicago Tribune, June 13, 1980: C2.

28 Bob Markus, “Chisox Count on Cruz at SS,” The Sporting News, December 20, 1980: 46.

29 “Cruz Suspect in Off-Field Theft,” Philadelphia Daily News, May 21, 1981: 78.

30 Robert Markus, “Bright Dream Only Painful Memory for Sox’s Cruz,” Chicago Tribune, May 5, 1981: C1.

31 Steve Kelley, “Errors Off the Field Have Held Back Todd Cruz,” Seattle Times, July 24, 1985: F1.

32 Robert Markus, “Cruz Paying for His Arrest, on the Field as Well as Off,” Chicago Tribune, May 22, 1981: C3.

33 Robert Markus, “Cruz: I had a Few Drinks and Let Things Get to Me,” Chicago Tribune, May 21, 1981: C1.

34 Jerome Holtzman, “He Needed Rehabilitation,” Chicago Sun-Times, May 20, 1981: 81.

35 Robert Markus, “Cruz’s Arrest Shocks White Sox,” Chicago Tribune, May 20, 1981: C1.

36 Markus, “Cruz: I had a Few Drinks and Let Things Get to Me.”

37 Markus, “Cruz Paying for His Arrest, on the Field as Well as Off.”

38 Markus, “Cruz: I had a Few Drinks and Let Things Get to Me.”

39 “Todd Cruz on Probation for Theft in Edmonton,” New York Times, July 15, 1981: B7.

40 1984 Baltimore Orioles Media Guide: 111.

41 Mark Whicker, “Cruz Hopes He’s Found a Home,” Philadelphia Daily News, October 13, 1983: 93.

42 Tracy Ringolsby, “Mariners Finally Getting Respect,” The Sporting News, June 28, 1982: 37.

43 Joseph Durso, “Plays, Double Plays Executed with Flair,” New York Times, July 23, 1982: A18.

44 Larry Millson, “This ‘Stooge’ Fits his Third Base Role,” Globe and Mail, October 14, 1983: 19.

45 Ray Parrillo, “Cruz Whips Up Lather for Orioles,” Baltimore Sun, July 2, 1983: B2.

46 Richard Justice, “Would the Real Todd Cruz Please Stand Up?” Baltimore Sun, March 29, 1984: B1.

47 Justice, “Would the Real Todd Cruz Please Stand Up?”

48 Parrillo, “Cruz Whips Up Lather for Orioles.”

49 Cruz, Publicity Questionnaire (1987).

50 Mike Klingaman, “Ex-Orioles Infielder Todd Cruz Dead at 52” Baltimore Sun, September 5, 2008 https://www.baltimoresun.com/sports/orioles/bal-sp.cruz05sep05-story.html (last accessed February 4, 2021).

51 1984 Baltimore Orioles Media Guide: 111.

52 Millson, “This ‘Stooge’ Fits his Third Base Role.”

53 Justice, “Would the Real Todd Cruz Please Stand Up?”

54 Kent Baker, “Cruz, Bat Earns High Marks at Rowe’s ‘Winter School’,” Baltimore Sun, November 13, 1983: B2.

55 Parrillo, “Cruz Whips Up Lather for Orioles.”

56 Justice, “Would the Real Todd Cruz Please Stand Up?”

57 Richard Justice, “Cruz Calls in Sick in Seventh Inning,” Baltimore Sun, August 26, 1984: 7B.

58 Kantowski, “Old Pro’s Story Ends Humbly in Desert Town.”

59 Justice, “Cruz Calls in Sick in Seventh Inning.”

60 Whicker, “Cruz Hopes He’s Found a Home.”

61 Richard Justice, “Todd Cruz to Get Shot at Becoming Pitcher,” Baltimore Sun, September 13, 1984: 3E.

62 Richard Justice, “Cruz in Fined for Skipping Practice,” Baltimore Sun, March 5, 1985: 6C.

63 Richard Justice, “Todd Not Yet in Cruz Control,” Baltimore Sun, March 2, 1985: 1C.

64 Joe Robbins, “Notebook,” Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, New York), June 2, 1985: 77.

65 Todd Cruz, Publicity Questionnaire for William J. Weiss, July 9,1986.

66 Tom Jones, “SPBA Calls it a Season,” St. Peterburg Times, December 27, 1990: C1.

67 Frank Fitzpatrick, “For Substitute Phils, It Was Sunny Side Up,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 2, 1995: C1.

68 Jay B. Kitchen, “Former Major Leaguer Todd Cruz Helping Youth Accomplish Dreams,” Precinct Reporter (San Bernardino, California), July 11, 2002: 9.

69 Kantowski, “Old Pro’s Story Ends Humbly in Desert Town.”

70 Klingaman, “Ex-Orioles Infielder Todd Cruz Dead at 52.”

71 “Medical Examiner Says Athlete Died of Disease,” Las Vegas Review-Journal, November 8, 2008, https://www.reviewjournal.com/news/in-brief-2183/ (last accessed February 11, 2021).

72 Kantowski, “Old Pro’s Story Ends Humbly in Desert Town.”

Full Name

Todd Ruben Cruz

Born

November 23, 1955 at Highland Park, MI (USA)

Died

September 2, 2008 at Bullhead City, AZ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.