August 14, 1949: In an upset, East stars defeat West in 17th annual East-West Classic

In the summer of 1949, preparation was underway for one of the most popular Negro Leagues events: the East-West Classic. The annual all-star game – which had been held at Chicago’s Comiskey Park every year since 1933 – had long been a fan favorite.1 In August 1948, more than 42,000 had turned out to watch it. That was a smaller crowd than in 1947, when more than 48,000 attended, but it was still a very respectable number.

In the summer of 1949, preparation was underway for one of the most popular Negro Leagues events: the East-West Classic. The annual all-star game – which had been held at Chicago’s Comiskey Park every year since 1933 – had long been a fan favorite.1 In August 1948, more than 42,000 had turned out to watch it. That was a smaller crowd than in 1947, when more than 48,000 attended, but it was still a very respectable number.

Owners were hopeful that the 1949 “Dream Game” would once again demonstrate its drawing power. Members of the East team, which had lost at Comiskey for the past six years,2 were hopeful that this time they’d snap the losing streak.

And many players on both squads were hopeful that it would provide a showcase for their skills. Even though only the Brooklyn Dodgers, Cleveland Indians, and New York Giants deployed integrated major-league rosters in August 1949, several scouts from National and American League teams had attended the 1948 game, including John Rigney, director of the Chicago White Sox farm system;3 more scouts were expected in 1949. “There will be a contingent of Major League scouts on hand to ‘eye’ the players in this game and it is likely that a number will be signed by Major League clubs,” Wendell Smith wrote in the Pittsburgh Courier.4

But despite the excitement about the all-star game, there were signs that all was not well in the Negro Leagues. Ever since Jackie Robinson and Larry Doby had broken baseball’s color barrier in 1947, Negro Leagues owners had grown increasingly worried that losing their best players would lead to a decline in fan interest. They had reason to be concerned: In 1948, financial struggles caused the New York Black Yankees to cease operating, and longtime owners Effa and Abe Manley sold the Newark Eagles.

By the end of the year, the Negro National League had disbanded.5 Several teams, like the Homestead Grays, focused on barnstorming, while others, including the New York Cubans and Baltimore Elite Giants, merged into the Negro American League, playing in the newly created Eastern Division.6

In past years, the East squad had consisted of players from the Negro National League and the West squad came from the Negro American League. In 1949 the East was made up of players from the Negro American League’s Eastern Division, and the West from its Western Division. There were still many big names in the Negro Leagues, and the rosters reflected that. Four players on the East had played in the 1948 Classic. They included up-and-coming second baseman Junior Gilliam and shortstop Pee Wee Butts, both from the Baltimore Elite Giants; catcher Bill Cash from the Philadelphia Stars; and pitcher Pat Scantlebury from the New York Cubans.

Four players on the West had also been all-stars in 1948: pitcher Jim Lamarque of the Kansas City Monarchs; his teammate, outfielder Willard Brown; first baseman Bob Boyd of the Memphis Red Sox; and Birmingham Black Barons player-manager Piper Davis.

Wendell Smith was among the sportswriters who gave the West the edge, in part because its pitching staff was so strong: both Lamarque and Gread McKinnis of the Chicago American Giants had won 10 games. McKinnis, who already had 74 strikeouts, was considered “one of the best left handed [pitchers] in the league.”7

Smith also believed the West had a stronger offense than the East. A few days before the Classic, Piper Davis was leading the Western Division in hitting with a batting average hovering around the .400 mark. Willard Brown – part of the St. Louis Browns’ brief integration two seasons earlier – was hitting .353, with 11 homers;8 outfielder Pedro Formental of the Memphis Red Sox was hitting .347; Bob Boyd was hitting .341; and catcher Lonnie Summers of the Chicago American Giants was batting .317.

In addition to good hitters, the West team also had solid fielders: Davis was “agile” and “sensational” at second, and Ducky Davenport of Chicago was “the fastest outfielder in the game.”9

But the East squad would not be a pushover. Manager Jesse “Hoss” Walker of the Elite Giants was confident. He believed it would be the East’s year.10 Sportswriter Russ Cowans agreed with him. Cowans mentioned Elite Giants first baseman Lenny Pearson, who was batting an impressive .369; and his Baltimore teammate, left fielder Bob Davis, was batting .379, with 46 RBIs. Davis was “not the easiest fellow for a pitcher to face.” Cowans also noted that Gilliam was batting over .300, and so was right fielder Bus Clarkson of the Philadelphia Stars. And as for pitching, the East had Bob Griffith of the Stars; he was both a good hitter, currently batting .310, and a very effective pitcher, with a record of seven wins and just one loss. Cowans concluded that the East was “no weak team. [It has] “plenty of power at the bat and on the mound.” And Cowans was so impressed with the rosters of both teams that he was sure attendance for the Classic would exceed 45,000 fans.11

Sunday, August 14, was a beautiful day for a ballgame, sunny, with temperatures in the low 80s. For the first time at any East-West Classic, the commissioner of baseball, Albert B. “Happy” Chandler, was invited by Negro American League President J.B. Martin to throw out the first ball, in recognition of his role in supporting baseball’s integration.12 A month earlier, on July 12, Chandler had been at Ebbets Field for the first-ever integrated All-Star Game,13 featuring former Negro Leaguers Robinson, Doby, Don Newcombe, and Roy Campanella.

The starting pitcher for the East was Griffith, while the West countered with left-hander Gene Richardson of the Monarchs. The East squad wasted no time, scoring a run in the top of the first, helped by Richardson’s wildness. He walked Butts and New York Cubans outfielder Pedro Díaz14 on eight pitches15 and Butts scored on a Clarkson single. It could have been worse. Before Clarkson’s hit, Pearson slugged a long fly to deep left center, but Willard Brown made a running catch, “spearing the ball while going at breakneck speed.”16

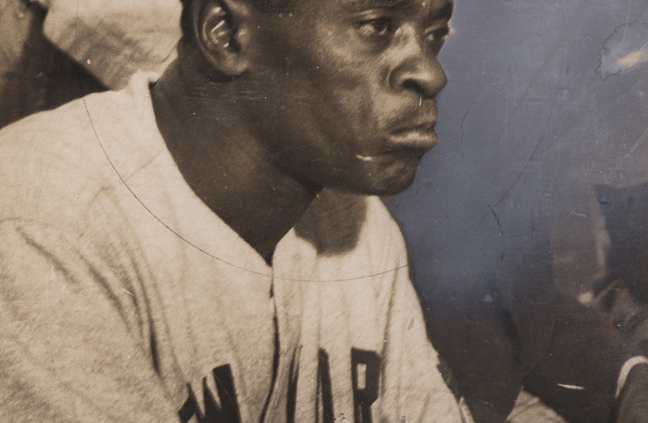

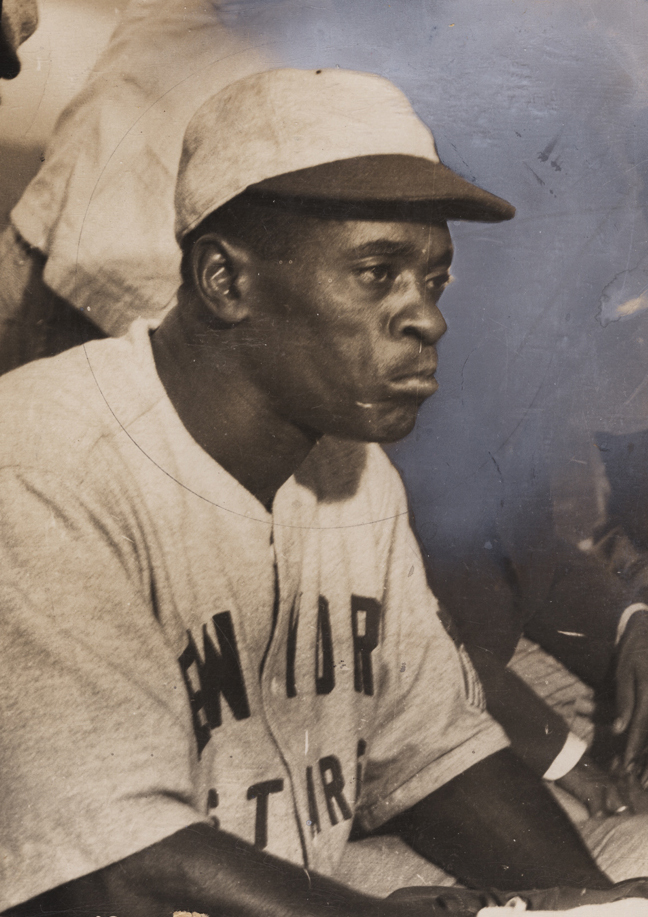

In the second, the East scored again. Third baseman Howard Easterling of the Cubans singled, stole second, and came home on a single from Griffith to make it 2-0. Meanwhile, the West could do nothing with Griffith, who pitched three scoreless and hitless innings. He was succeeded by Andy Porter of the Indianapolis Clowns, but the West couldn’t hit him either.

It wasn’t until the seventh inning with two out that the West got a hit – a double by 32-year-old second baseman Piper Davis17 off Scantlebury, the East’s third pitcher. But a great defensive play by right fielder Sherwood Brewer of the Indianapolis Clowns kept it from being a triple,18 and it didn’t lead to a run; nor did the other hit the West got off Scantlebury, in the bottom of the eighth, a single by Summers.

Meanwhile, the East had tacked on two more runs in the top of the eighth, when Brewer hit a line drive off pitcher McKinnis’s glove, Bob Davis singled to right and Brewer came home on a long fly by Gilliam. And that was all the scoring, in a game that was dominated by the East from start to finish. In shutting out the West 4-0 and snapping its losing streak, the East got 11 hits (three of them by Díaz), while the West could manage only two. Starting pitcher Griffith took the win for the East, and Richardson was the losing pitcher for the West.

The scouts in the stands had seen many impressive plays, especially by the East, which repeatedly demonstrated timely hitting, excellent pitching, and solid fielding. But the expected crowd of more than 40,000 did not materialize. Only about 31,000 saw the game,19 and Wendell Smith believed it was actually closer to 26,000.20

The continued decline in attendance did little to calm the worries of the owners. Sportswriters too wondered if this was a sign of “the waning … popularity of Negro baseball.”21 Luix Virgil Overbea of the Atlanta Daily World lamented the absence of several stars – Bob Thurman, Earl Taborn, Alonso Perry, and Booker McDaniel – whom Negro American League owners had recently sold to National and American League clubs. “What excellent additions to the all-star lineups if only the owners had waited a month,” Overbea wrote.22

And the exodus of talent was not stopping. On the day after 1949’s Dream Game, the Boston Red Sox announced that Piper Davis, one of the Negro Leagues’ most popular players,23 had signed with their Double-A Scranton club.24

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank John Fredland, Gary Belleville, and Kurt Blumenau for their helpful suggestions. This article was fact-checked by Jim Sweetman and copy-edited by Len Levin.

Photo credit: Howard Easterling, SABR-Rucker Archive.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com, Seamheads.com, Newspapers.com, GenealogyBank.com, and Retrosheet.org for pertinent information, including the box scores and play-by-play.

https://retrosheet.org/NegroLeagues/boxesetc/1949/B08140ASW1949.htm

Notes

1 In several seasons a second East-West All-Star Game had been played at another ballpark: 1939 at Yankee Stadium, 1942 at Cleveland Stadium, 1946 at Griffith Stadium, 1947 at the Polo Grounds, and 1948 at Yankee Stadium.

2 Bob Luke, The Baltimore Elite Giants: Sport and Society in the Age of Negro League Baseball, (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009), 120-121.

3 Frank Mastro, “Negro All-Star Nines Clash Again Tonight,” Chicago Tribune, August 24, 1948, part 2: 4.

4 Wendell Smith, “Players Battle for Berths on East-West Teams: ‘Dream Game’ Set for Chicago on August 14,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 16,1949: 23.

5 “Grays Quit League, New Circuit Formed,” Washington Afro-American, December 4, 1948, Section 2: 12.

6 Rich Puerzer, “September 26-October 5, 1948: Homestead Grays Capture Final Negro League World Series in Five Games,” SABR Games Project, https://sabr.org/gamesproj/game/september-26-october-5-1948-homestead-grays-capture-final-negro-league-world-series-in-five-games/. Accessed July 12, 2024.

7 Wendell Smith, “West Early Favorites to Win East-West Classic,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 30, 1949: 22.

8 “Chandler to Start East-West Classic,” Detroit Tribune, August 13, 1949: 8.

9 Wendell Smith, “Baseball Czar Will Throw First Ball,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 13, 1949: 22.

10 “East-West Game on Tap Sunday Out in Chicago,” New York Age, August 13, 1949: 25.

11 Russ J. Cowans, “Expect Crowd Of 45,000 at East-West Classic: Strong Teams to Be Fielded by Both Clubs,” Chicago Defender, August 13, 1949: 14.

12 “Commissioner Chandler to Attend East-West Game: 40,000 Expected at Classic; Baseball Czar to Toss Out First Pitch,” Kansas City Call, August 12, 1949: 8.

13 “A Must,” New York Daily News, July 13, 1949: 86.

14 According to Baseball-Reference.com, Díaz was known by several names: Fernando Díaz Pedroso, Fernando Díaz, and Pedro Díaz. In 1949, newspapers were referring to him as Pedro Díaz.

15 Marion E. Jackson, “East Upsets West 4-0 in 17th Annual Competition in Comiskey Park, Chicago: Superb Pitching, Fielding Feature Classic Exhibition,” Atlanta Daily World, August 16, 1949: 5.

16 Wendell Smith, “East-West All-Star Dust,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 20, 1949: 22.

17 While all the newspapers that covered the East-West Classic, including the Chicago Tribune, Atlanta World, St. Louis Argus, Pittsburgh Courier, and New York Age, reported that Davis was the West team’s manager in the 1949 East-West Classic, historian Larry Lester subsequently found photographic evidence that indicated it was actually Buck O’Neil who managed the team that day, rather than Davis. Lester cited that evidence in both the 2002 version (334) and the revised 2020 version (307) of his book Black Baseball’s National Showcase.

18 Arthur “Devil” Kirk, “East Snaps West’s Win String With a Shutout,” St. Louis Argus, August 19, 1949: 21.

19 BR Bullpen, “1949 East-West Game,” Baseball-Reference.com, https://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/1949_East-West_Game. Accessed August 7, 2024. In the newspapers, attendance figures varied, with a lot of estimates from 30,000 to 35,000.

20 Wendell Smith, “East-West All-Star Dust,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 20, 1949: 22.

21 Luix Virgil Overbea, “East-West Game Barometer Shows Game Faces ‘Dunkirk,’” Atlanta Daily World, August 23, 1949: 5.

22 Overbea, “East-West Game Barometer Shows Game Faces ‘Dunkirk.’”

23 “Club Owners Select Davis as Team Coach,” Michigan Chronicle (Detroit), July 16, 1949: 10.

24 “Piper Davis Signed by Bosox Chain Club,” Birmingham (Alabama) News, August 15, 1949: 18.

Additional Stats

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.