Bill Engeln

Imagine being able to say you’d seen the big-league debuts of Ernie Banks, Roberto Clemente, Sandy Koufax, Don Drysdale, and Bill Mazeroski1 – not to mention an All-Star Game, a no-hitter, a four-homer game, and a batter hitting for the cycle. Some baseball lovers spend a lifetime hoping to see those kinds of milestones.

Bill Engeln loved baseball, and his skill as an umpire lifted him out of the nine-to-five world and carried him to the National League from 1952 to 1956. He worked 752 big-league games,2 including all of the events listed above.3 They might be considered rewards for his more than 16 seasons4 in the minor leagues, during which a world war and behind-the-scenes politics stalled his progress and frustrated him.

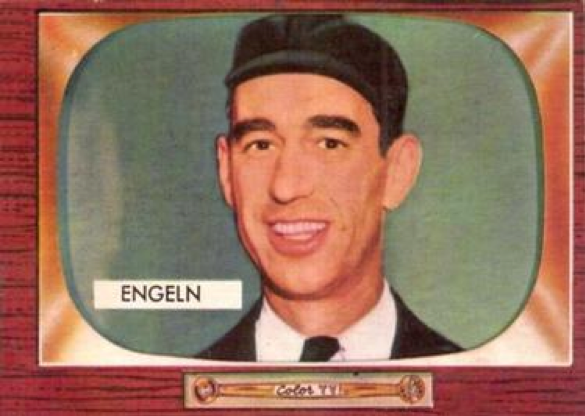

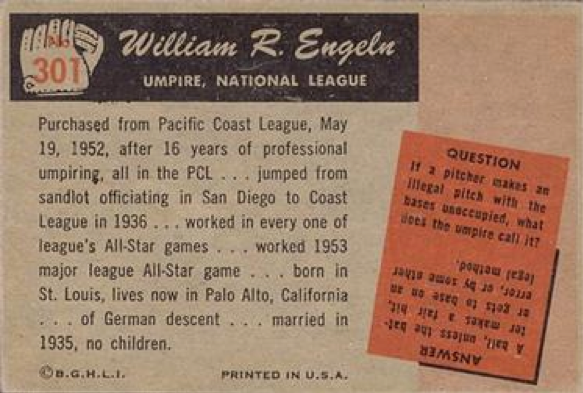

Engeln also reached the majors at just the right time for an unusual and lasting claim to fame. He was one of 31 umpires immortalized in cardboard in the 1955 Bowman baseball-card set, one of the few major card sets to include umps. Smiling benignly from the front of card 301, Engeln looked like the clerk he had once been, rather than a man who had spent two decades being shoved, screamed at, pelted with bottles, and menaced by fence-jumping fans.5

William Raymond Engeln was born on September 9, 1898,6 in St. Louis, Missouri. He was the last of seven children – five girls, two boys – born to Bernhardt Engeln and his wife, the former Mary Fleiter.7 Bernhardt Engeln (called Bernard in some sources) emigrated from Germany in 1867 and was naturalized as a U.S. citizen in 1888. He worked as a firefighter for the city of St. Louis.8

Bill Engeln’s age took on a curious flexibility once he became a professional umpire. Profiled in The Sporting News in January 1942, he claimed to be 39, four years younger than he was.9 His Sporting News umpire card went further, trimming six years off his age and listing his birth date as September 9, 1904.10 Newspaper references to his age during his NL career were consistent with one or the other of these “adjusted” birthdays, often the latter. Engeln didn’t start as a pro umpire until he was 37, and it seems probable that he indulged in the once-common practice of fudging his age to make himself seem younger. This deception might have helped him reach the major leagues.

But, back to his boyhood. Engeln showed up in St. Louis newspapers at age 15 in the spring of 1914, playing left field for the Bryan Hill School team as part of a newspaper-sponsored public school baseball tournament.11 Unfortunately, Bryan Hill lost in a semifinal game, picking up only three hits – one by Engeln.12 The Bryan Hill squad missed out on a big prize, as the championship game was to be played in one of the city’s major-league ballparks and umpired by members of the Browns or Cardinals.13 Instead, Engeln made his own connection to big-league ball, serving as a batboy for the Browns.14

Engeln’s playing talents were not enough for a professional career, and he advanced no further than semipro baseball15 while settling into a workaday life. His 1917-1918 draft card and the 1920 U.S. Census both list him as a railroad clerk in St. Louis.16 In November 1922 he married Alta Tritt of St. Louis,17 and two daughters followed: Laverne in 1928 and Mary in 1932.18 By the time their daughters arrived, the Engelns had resettled in the warmer climes of San Diego, where Bill initially worked as a freight claim agent in the shipping industry.19

Engeln’s umpiring career grew from modest roots. Meeting the president of the San Diego Umpiring Association, he was invited to help work a junior high school game. He fell in with local amateur umps and developed his skills calling college, semipro, and military games. Later, he modestly recalled, “I umpired my first game … just because two teams couldn’t agree on anybody else.”20

Those low-profile opportunities brought Engeln his big break, though the story varied from telling to telling. In one version, Pacific Coast League president W.C. Tuttle went to see his son pitch in a semipro game and was impressed by Engeln’s work.21 In another, Tuttle happened across a military game in San Diego and noted Engeln’s composure while surrounded by armed military guards.22 Either way, when Tuttle fired veteran ump Ernie Stewart early in the 1936 season, he called Engeln to replace him. Engeln set aside his reservations, along with his day job as a milkman,23 and made the leap from the sandlots to the PCL.24

It seemed like a poor decision at first, as fans, players, managers, and reporters strafed the nervous newcomer with criticism. “The first month was hell,” Engeln later said.25 The Los Angeles Times described his early umping as “decidedly bad,” as fans pelted him with apples and oranges.26 The San Francisco Examiner called him “the wrongest umpire to visit these shores in years,” reporting that San Francisco Seals manager Lefty O’Doul had humiliatingly tripped Engeln from behind when the ump tried to escape an argument.27 In August, Seattle manager Walter “Dutch” Ruether stomped on Engeln’s feet with his spiked shoes and jerked the umpire’s mask off. Tuttle suspended Ruether for the rest of the season, then shortened the penalty to 10 days and a $50 fine.28 Years later, Tuttle recalled talking a dejected Engeln out of quitting after his first week. “We both had thick skins and a sense of humor,” Tuttle said.29

As if his rocky transition to professional umpiring wasn’t enough, Engeln might have had personal stress to deal with in this period. His marriage to Alta ended at some point between the birth of their second daughter in November 1932 and his remarriage to Katherine Litzenberger in June 1938.30 Engeln and Litzenberger remained married until his death; they had no children.

Engeln’s fortunes turned around quickly as he gained confidence and showed his skill. By July 1937, the Los Angeles Times was reporting that he had “blossomed into a very good arbiter.” Engeln admitted he had been “scared” and “plenty bad” when he took the job, and credited colleagues Jack Powell and Wally Hood for mentoring him.31 Soon Engeln was covering for Powell, rather than the other way around. Engeln shifted to work Powell’s assigned games in August 1937 after the former National League ump was first suspended, then fired, for being drunk on the field during a game in Sacramento.32

Tuttle touted Engeln as a candidate for the majors as early as January 1938.33 Some criticism of Engeln’s work lingered – the Oakland Tribune rapped him for “all-too-frequent hometown decisions”34 – and police had to shield him from mobs of angry fans on several occasions.35 But good reviews outweighed bad, like the Los Angeles Times’ judgment that he was “hustling every minute,”36 and both major leagues were said to be eyeing him.37 Tuttle broke the news in October 1941: President Will Harridge of the American League had invited Engeln to try out the following spring.38 In just six seasons, Engeln had gone from the whipping boy of the PCL to a candidate for the AL.

News items from that time provide glimpses of his personality and interests. “Bill lives and loves baseball,” one summarized.39 He was described as dapper – “perhaps the best dressed umpire in the business” – and a likable “good egg” who took his job seriously.40 Another scribe described him as “a human dynamo of energy who knows more about applied psychology than you find in some books,” as well as “an honest, conscientious workman.”41 The writer also noted that Engeln lived in Seattle and sold sporting goods in the offseason. One news item ended with a word of support for his tryout: “Don’t get stage fright, chum. A ball is a ball and a strike a strike.”42

The United States’ entry into World War II in December 1941 stopped Engeln from getting his big break. Tuttle announced in February 1942 that Engeln’s opportunity in the AL had been canceled and he would stay in the PCL, though Tuttle remained optimistic that the majors would come calling again soon.43 Others seemed to agree, like Connie Mack, who praised Engeln’s umping during a pair of March 1942 exhibitions between the Philadelphia A’s and the Sacramento Solons.44

The rumors lingered. After the 1943 season, the NL was said to be interested.45 But, as season followed season, the callup was slow to come. Engeln continued paying minor-league dues. His locker was broken into during a game in San Francisco in 1942, costing him $15.46 Two seasons later he had to corral a dog on the field.47 The following spring, he umpired a Sacramento Solons exhibition game at California’s Folsom Prison.48

At another point he and other umpires threatened to strike unless league president Tuttle reversed a threatened pay cut. This might not have been a popular stance in wartime – two major-league scouts told him, “If you don’t like your pay, join the Army”49 – but Engeln and other umps held their ground and got their money.50 It was not the last time Engeln would take a public stand regarding umpires’ pay. If nothing else, Engeln might have wanted the money to maintain his wardrobe: He was described as a Beau Brummel who wore $15 hats and $6 ties.51

Engeln earned praise for reading the mechanics of the game, so that either he or his partner was always in the right place to call the action.52 In March 1946, Engeln was assigned to umpire a series of San Francisco Seals exhibition games in Hawaii. The perks of the trip included a lavish birthday party and dinner for Seals manager O’Doul at Trader Vic’s restaurant in Honolulu – the same O’Doul who had tripped the hapless rookie Engeln a decade earlier.53 Engeln also reconnected with his long-ago playing days by suiting up in uniform at a workout and taking swings in the batting cage.54 His stay was briefly and uncomfortably extended when his plane back to the mainland developed engine trouble and had to return to Hawaii.55

As Engeln plugged away in the PCL, league president Clarence “Pants” Rowland led a quixotic campaign to get the loop recognized as a third major league. PCL cities like Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Seattle were growing fast, and Rowland and some of his owners were eager to elbow their way into first-class status.56 In October 1946, the league took an ad in The Sporting News with the chesty declaration, “This far Western Circuit has Grown into an Empire of Its Own. It deserves Major League Rating and is destined to receive it soon. Watch Us.”57 This campaign might have made Engeln’s long stay in the league easier to stomach: He might have perceived a route to the majors simply by staying where he was.

By 1949, though, Engeln’s frustration over being stuck in the PCL had reached a breaking point.58 Rowland sold less experienced ump Lon Warneke, a former pitcher with the Chicago Cubs and St. Louis Cardinals, to the NL that season. Engeln was “glad to see Lon get his chance, but he can’t help asking, what about me?” one reporter wrote.59 The same article mentioned that Engeln had moved to the San Francisco Bay Area, was selling clothes in the offseason, and was beginning to think about making a career of it.

An equally galling report in 1951 claimed that Engeln had been ticketed for the AL the previous season. But AL president Harridge canceled the promotion when word leaked out prematurely – even though PCL managers and players raved about Engeln. “It just goes to show you how little things can stymie a man’s career,” the item ended.60

Little things can revive a man’s career, too. During a Cardinals-Cincinnati Reds game on April 22, 1952, Cardinals manager Eddie Stanky and umpire Scotty Robb got into a shoving match. Robb reportedly pushed first, and NL President Warren Giles – who witnessed the altercation – issued Robb an unspecified but hefty fine.61 Robb submitted a one-sentence note of resignation on May 6.62

Giles filled the vacancy by purchasing Engeln’s contract on May 19.63 The ump flew to Cincinnati and made his long-awaited major-league debut at another Cardinals-Reds matchup on the night of May 23, working at third base on a crew led by home-plate umpire and future Hall of Famer Jocko Conlan. Engeln was trailed by well wishes from across the PCL: “It would make Bill’s heart happy to know many people have expressed, by phone or mail, gratification that Bill finally received the recognition due him,” a journalist in Oakland wrote.64 Engeln was reported to be 47 years old; he was 53.65

Engeln’s first big-league season passed routinely, with one exception. On July 31, New York Giants catcher Sal Yvars pushed Engeln while protesting a call at home plate. Yvars was ejected and fined $100.66 It was one of four ejections for Engeln in his first season. He racked up 15 over his five-season career.

Engeln worked a July exhibition in Rochester, New York, in which the Boston Red Sox and Cardinals raised $15,000 for former big-leaguer George “Specs” Toporcer, who had gone blind in retirement.67 Engeln and colleagues Dusty Boggess, Babe Pinelli, and Lou Jorda were also featured in a two-page photo spread about umpires in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Engeln was shown sitting in the stands before the game, wearing a stylish hat,68 watching players in order to enforce the league’s ban on pregame fraternizing.69

Engeln drew his most prominent assignment in 1953, working right field during the All-Star Game at Crosley Field. When the Cardinals’ Enos Slaughter made a dramatic diving catch in the sixth inning, Engeln was there to make the out call – and show up as a blurred black figure on the outer edges of wire-service photos.70 He was also working at first base at the Polo Grounds on September 6, when Brooklyn’s Carl Furillo charged the Giants’ dugout and wrestled with Giants manager Leo Durocher. Furillo broke his hand in the brawl, but his .344 average at the time of his injury stood up as the NL’s best that season.71 In the offseason Engeln returned to his adopted home of Palo Alto, California, where he took part in a sports fundraising dinner and worked in a men’s clothing store called Wideman’s.72

Engeln’s career heated up, on the field and off, in 1954. Speaking at a press luncheon in February, he called on the PCL to raise umpire salaries: “Everybody back east wants to know why the Coast League doesn’t pay more. …Underpaid umpires are going to grumble on the field. Raise their pay and they’ll hustle harder. … It’s a good league for umpires, too. Nice climate, a week in a town at a time, everything’s OK but the pay.”73 Engeln’s frankness reportedly angered NL president Giles.74 While Engeln’s press notices remained generally positive, he landed on the bad side of the New York Daily News’s acerbic Dick Young, who needled him in April for calling plays prematurely.75

On the field, Engeln worked some of the year’s most memorable regular-season games. He was at third base at Milwaukee’s County Stadium on June 12 when the Braves’ Jim Wilson no-hit the Philadelphia Phillies, 2-0.76 He umped at second base at the Polo Grounds on July 11, when the Giants’ Don Mueller hit for the cycle against the Pittsburgh Pirates. He worked first base at Ebbets Field on July 31 when Milwaukee’s Joe Adcock hit four home runs against Brooklyn. He worked behind the plate the following day when the Dodgers’ Clem Labine beaned Adcock.77 Benches emptied, but no one was ejected.

Engeln began 1955 by again speaking his mind on baseball matters – specifically, chiming in on a debate about preventing slow play by pitchers. In remarks that were published nationally, Engeln observed that batters also slowed down play by stepping out of the box, and if pitchers were to be penalized for slow play, batters should be as well.78

He also landed, amusingly, in a Sporting News story raising the question of whether umpires should wear glasses on the field. According to a New York vision institute, 71 percent of American men over 50 needed some form of vision correction. Engeln’s age was given as 50 in the article. He was actually 56, which made him the second-oldest ump in the NL, behind 59-year-old Pinelli.79

At the end of the year, Engeln was asked to name his most thrilling sports moment of 1955, and his choice is telling. The umpire listed Stan Musial’s 12th-inning homer in the All-Star Game, played in Milwaukee. “It was worth the trip to Milwaukee just to see that ball go over the fence,” he said.80 The answer is interesting because Engeln wasn’t chosen to call the game, nor did he work in Milwaukee immediately before or after the All-Star break. It appears that he went to see the game on his own, as a fan.81 (This was in character: In 1947, Engeln told a reporter that he spent off-days going to baseball games to watch other umps work. “That’s the best way to improve yourself,” he said.)82

Comments made by Pirates catcher Jack Shepard before the season also shed light on Engeln’s kindly personality. Like Engeln, Shepard had ties to Palo Alto, having starred at Stanford University before reaching the majors. Shepard credited Engeln for giving him friendly advice: “Don’t worry about a thing. Just imagine you are back at Stanford and don’t press.” “That was good advice. I frequently did just that,” Shepard added.83

The Palo Alto newspaper greeted the 1956 season with a photo of Engeln packing up his whisk broom to go to spring training, along with some frank talk. He noted that the pressure on umpires was “terrific,” and games demanded “so much concentration that one is worn out at the end of the playing time.” He also grumbled about the travel, noting that he was required at the end of the exhibition season to go from Fort Smith, Arkansas, to Pittsburgh, to Milwaukee, and then to Cleveland in a span of four days. “That traveling from city to city can be murder,” he said.84

Dissension among NL umpires had been building up for other reasons. The New York Daily News reported that season that the umps were “disgusted over low pay,” as well as by Giles’ refusal to appoint a supervising umpire. These complaints reportedly crossed over onto the field, with umpires quick to eject players because they didn’t feel they were getting paid enough to tolerate beefs.85 The umps, further, had been banned from talking to reporters.86

Amid this pressurized atmosphere, Engeln added another minor distinction to his resume on April 19. The Dodgers, trying to pressure New York City into a new ballpark, booked a handful of 1956 and 1957 games at Roosevelt Stadium in Jersey City, New Jersey. Engeln umpired at first base for the first of these games, a 5-4 Dodgers victory over the Phillies on April 19.

Beyond that, his most noteworthy game was probably a dustup between the Cubs and Braves in the first game of a doubleheader on May 30. After three straight Milwaukee batters homered off Chicago’s Russ Meyer, Meyer threw high and inside at the next batter, Bill Bruton. Engeln did not issue a warning to Meyer after the first pitch, and the next pitch hit Bruton in the head. Some reporters faulted Engeln for not warning Meyer after the first beanball attempt, saying it might have prevented the second.87

Engeln’s season ended quietly on September 30, when he worked first base at a Braves-Cardinals game in his hometown of St. Louis. The game ended his career as well. On December 20, Giles announced the hiring of umpires Ken Burkhart and Tony Venzon to replace Artie Gore and Engeln. Gore was retiring, Giles said, while Engeln was leaving baseball to devote himself full-time to business opportunities in Palo Alto.88

Gore quickly contradicted Giles, making clear he had been fired.89 Others assumed Engeln must have been canned as well. One scribe wrote of Gore and Engeln, “It is obvious they were pushed.”90 Jim McCulley of the New York Daily News, who chronicled the umps’ dissatisfaction earlier that season, wrote that Engeln “let it be said” that he resigned to go into private business. McCulley added: “I believe he never was cut out for the job of umpiring. He was completely honest in his convictions, but too soft-hearted and gentle to cope with some of the pompous jerks in baseball today.”91 Former umpire Larry Goetz prolonged the debate in 1961 by including Engeln’s name in a list of umps “fired or forced to retire” in the previous decade.92

Did Giles push Engeln out the door? It’s possible; Engeln reportedly irked Giles with his comments on PCL umpire pay, and his complaints about travel might have struck a nerve as well.

On the other hand, Engeln never contested Giles’s explanation of his departure. He more or less confirmed it. Engeln discussed his retirement with reporters several times, and the reasons he gave – travel fatigue, declining eyesight, and the opportunity to take a bigger role in Wideman’s clothing store – are entirely plausible, especially for a man approaching 60.93 (Keep in mind that the reporters who reached conclusions about Engeln’s departure thought he was six years younger than he really was.)

It briefly appeared that Engeln would be back on the field in 1957. The Pacific Coast League stationed its umpires in the same city for at least one week and sometimes two,94 which eliminated Engeln’s biggest complaint about big-league life. PCL president Leslie O’Connor offered Engeln a contract in February 1957.95 Engeln admitted in June that he missed the game badly and was tempted to return, but finally told O’Connor to stop calling him “because I was afraid I might say ‘yes.’”96

After leaving baseball, Engeln worked at Wideman’s and served as commissioner of the Menlo Park Babe Ruth youth baseball league. He received another round of national press in 1963 after telling a reporter that major league baseball would die within five years if it replaced human umpires with robots or machines.97 He said the move of the New York Giants to San Francisco in 1958 did not rekindle his interest in umpiring. But, a baseball fan to the end, he made several references in interviews to going to see Giants games.98

April 17, 1968, was a landmark date in Northern California baseball history. The Oakland A’s, newly arrived from Kansas City, played their first home game,99 bringing American League baseball to the San Francisco Bay Area – a decade after the Giants did the same for the NL. That night the A’s hosted the Baltimore Orioles, formerly the St. Louis Browns. But Bill Engeln, the St. Louis native and Bay Area transplant who lived and loved baseball, didn’t live to see the A’s arrival in their new home city. He died on the afternoon of April 17, 1968, of a heart attack suffered at his home in Palo Alto. Newspaper obituaries listed his age as 67; he was 69.100

Engeln was survived by his wife, two daughters, two grandchildren, and three siblings. He was buried in Colfax, Washington, home of his father-in-law. His death listing in the Palo Alto newspaper steered memorial contributions to the Babe Ruth League of Menlo Park.101

Acknowledgments

This story was reviewed by Rory Costello and Rick Zucker and checked for accuracy by members of SABR’s fact-checking team.

Sources and photo credits

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference and Retrosheet for information on games, teams, and seasons.

Photos of 1955 Bowman card #301 downloaded from the Trading Card Database.

Notes

1 To be specific, Engeln umpired at third base for Banks’ first game on September 17, 1953; at home plate for Clemente’s first game on April 17, 1955; at second base for Koufax’s first game on June 24, 1955; at second base for Drysdale’s first game on April 17, 1956; and at third base for Mazeroski’s first game on July 7, 1956.

2 The figure of 752 games includes 751 regular-season games and the 1953 All-Star Game. (Engeln never worked a World Series.)

3 Engeln also umpired future Hall of Fame manager Walter Alston’s first game as Brooklyn Dodgers skipper on Opening Day, 1954. It was not technically Alston’s big-league debut, as he’d appeared in a single game as a player with the St. Louis Cardinals in 1936.

4 Engeln umpired in the Pacific Coast League from 1936 to 1951, and also began the 1952 season there before the NL purchased his contract on May 19.

5 A brief history of umpire cards in baseball-card sets, and an extended look at the 1955 Bowman umpire cards, can be found in Jason Schwartz, “The Umpires of 1955 Bowman,” SABR’s Baseball Cards Research Committee blog, posted October 5, 2021, and accessed January 8, 2023.

6 In addition to Baseball-Reference and Retrosheet, this birth date is given on his 1917-1918 draft card, accessed through Familysearch.org on January 8, 2023. Engeln’s listed ages in the 1910, 1920, and 1930 U.S. Censuses are consistent with this September 1898 birth date.

7 Various sources, including records on Familysearch.org; Bernhardt Engeln’s obituary, published in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 9, 1930: 1E; and Mary (Fleiter) Engeln’s obituary, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 19, 1939: 8C.

8 Naturalization information from 1920 U.S. Census entry for Bernhardt Engeln, accessed through Familysearch.org January 8, 2023. Job information from Census entry and Bernhardt Engeln’s obituary, cited above.

9 John B. Old (yes, that’s the byline), “Jumps to Majors from Semi-Pros In Six Years,” The Sporting News, January 29, 1942: 2.

10 The Sporting News umpire card for Bill Engeln, accessed via Retrosheet January 8, 2023. The date of Engeln’s marriage to Katherine Litzenberger is also incorrect on his TSN umpire card; official records indicate they were married in 1938, not 1937. Engeln’s 1955 Bowman trading card – like the other umpire cards in the set – does not include his birth date.

11 He is mentioned by name in “Additional Time Granted Schools to Enter League,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 27, 1914: 18. Bryan Hill School is located in St. Louis’s College Hill neighborhood, in the northeastern part of the city, not far from Sportsman’s Park. At the time this story was written in January 2023, the building was still being used as an elementary school under the name Bryan Hill.

12 “Marquettes, Delmars Win in School League,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, May 24, 1914: 13.

13 “Big League Players to Umpire the Game” and “Marquettes and Delmars Win in the Semi-Finals,” both St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 24, 1914: 32.

14 This statement appears in various news stories, including an uncredited wire-service item printed in newspapers across the US in 1952 and 1953 following Engeln’s ascent to the majors. It also appears in obituaries of Engeln. In a Newspapers.com search in January 2023, the author was unable to find any specific reference at the time of Engeln’s youth that cited him as a Browns batboy. That doesn’t disprove Engeln’s story, though: Batboys are rarely if ever mentioned in news coverage, and it’s possible that reporters covering the Browns simply had no reason to talk to him or include him in their stories.

15 Old, “Jumps to Majors from Semi-Pros In Six Years;” Harold Westlund, “Coast League Umpire Tells How He Started in the Game,” San Luis Obispo (California) Telegram-Tribune, August 22, 1941: 5. An undated photo of a San Diego City League team including Engeln appears on page 120 of Bill Swank’s Baseball in San Diego: From the Plaza to the Padres (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2005).

16 Draft card and 1920 U.S. Census listing accessed via Familysearch.org and cited above.

17 “Engeln-Tritt,” Belleville (Illinois) Daily Advocate, December 1, 1922: 2.

18 Sources include California Birth Index information for Mary Joanne Engeln, accessed through Familysearch.org January 9, 2023; the 1930 U.S. Census listing for Bill, Alta, and Laverne Engeln, also accessed through Familysearch.org; and “Church Wedding for Mary Engeln and Jack Burns,” Belleville (Illinois) News-Democrat, September 12, 1953: 5.

19 1930 U.S. Census, cited above. The census lists the nearly-two-year-old Laverne Engeln’s birthplace as California, suggesting that her parents had been living there for a few years as of 1930.

20 Old, “Jumps to Majors from Semi-Pros In Six Years;” Westlund, “Coast League Umpire Tells How He Started in the Game;” Al Wolf, “Coast Loop Umpiring Staff May Shrink One,” Los Angeles Times, January 19, 1942: 14.

21 Westlund, “Coast League Umpire Tells How He Started in the Game.”

22 Old, “Jumps to Majors from Semi-Pros In Six Years.”

23 “National League Buys Contract of Bill Engeln, PCL Umpire,” Sacramento Bee, May 19, 1952: 26; Paul Zimmerman, “Student Finds Umpires Are of Human Descent,” Los Angeles Times, June 2, 1949: II: 5.

24 Old, “Jumps to Majors from Semi-Pros In Six Years;” “Tuttle Fires Umpire for Being ‘Homesick,’” Los Angeles Times, April 22, 1936: II: 9.

25 Old,“Jumps to Majors from Semi-Pros In Six Years.”

26 Bob Ray, “Angels Rap Seals, 12-5,” Los Angeles Times, May 10, 1936: II: 9.

27 Harry Borba, “O’Doul Clips Umpire, Banned from Game as Seals Lose 12 to 5,” San Francisco Examiner, May 10, 1936: SF: 1; Harry Borba, “Engeln’s Decision Elicits Criticism,” San Francisco Examiner, May 10, 1936: SF: 4. Borba reported that Engeln had, a few nights earlier, called a walk on a batter who swung at a third strike.

28 United Press, “Reuther Ousted for Ump Attack; May Get Layoff,” Long Beach (California) Sun, August 10, 1936: B4; Associated Press, “Tuttle Lifts Suspension on Seattle Pilot,” San Bernardino County (California) Sun, August 15, 1936: 15.

29 “Tuttle Recalls How Courage Helped an Umpire to Majors,” The Sporting News, August 22, 1956: 15. This article suggests that Engeln was unemployed when Tuttle hired him: “Those were the days of the WPA and tight belts. He needed a job – and I needed an umpire.”

30 Whitman County, Washington, marriage record for William Engeln and Katherine Litzenberger, June 20, 1938, accessed through Familysearch.org on January 9, 2023. This record provides an early example of Engeln altering his age: He was 39 years old in June 1938, but is listed as 35.

31 Bob Ray, “The Sports X-Ray,” Los Angeles Times, July 19, 1937: 10.

32 United Press, “Tuttle Waits Evidence,” Oakland Tribune, August 21, 1937: 7. Powell was reinstated for the 1939 PCL season.

33 Associated Press, “Coast League ‘Ump’ Heads for Majors,” San Bernardino County Sun, January 27, 1938: 18.

34 Art Cohn, “Cohn-Ing Tower,” Oakland Tribune, March 28, 1938: 87.

35 Associated Press, “Police Guard Umpires,” Spokane (Washington) Spokesman-Review, June 14, 1937: 11; Associated Press, “Seals, Senators Beaten Again on Coast,” Reno Evening Gazette, September 23, 1937: 16; Lee Dunbar, “Police Called to Escort Arbiters from Ball Park,” Oakland Tribune, June 19, 1939: 9.

36 Bob Ray, “The Sports X-Ray,” Los Angeles Times, April 17, 1939: II: 11.

37 Ron Gemmell, “Sport Sparks,” Salem (Oregon) Statesman Journal, May 25, 1941: 6.

38 Associated Press, “Coast Umpire Goes to Majors,” Reno (Nevada) Gazette-Journal, October 22, 1941: 11.

39 Westlund, “Coast League Umpire Tells How He Started in the Game.”

40 Alan Ward, “On Second Thought,” Oakland Tribune, January 20, 1942: 22.

41 Old, “Jumps to Majors from Semi-Pros In Six Years.”

42 Ward, “On Second Thought.”

43 “Umpire Engeln to Stay on Coast,” Los Angeles Evening Citizen News, February 24, 1942: 17.

44 “L.A. Club President Thinks Solons are Team to Beat,” Sacramento Bee, March 14, 1942: 7.

45 Lee Dunbar, “On the Level,” Oakland Tribune, November 2, 1943: 17. Dunbar doesn’t identify his source, though it was likely league president Tuttle.

46 Abe Kemp, “Seal Game Postponed; Umps Robbed,” San Francisco Examiner, May 15, 1942: 18.

47 Wilbur Adams, “Between the Sport Lines,” Sacramento Bee, May 2, 1944: 10.

48 Wilbur Adams, “Between the Sport Lines,” Sacramento Bee, March 22, 1945: 22.

49 Lee Dunbar, “On the Level,” Oakland Tribune, June 21, 1943: 14.

50 “Umpires May Strike,” Long Beach Sun, June 29, 1943: 8; “‘Restore $25 Salary Slash by July 1 or We Quit,’ Coast League Umps Tell Tuttle,” San Francisco Examiner, June 29, 1943: 19; “Here’s News from Home,” Oakland Tribune, July 17, 1943: 11.

51 “Coast Circuit Provides the Unusual,” Van Nuys (California) News and Valley Green Sheet, July 20, 1943: 5. For context, an online inflation calculator provided by the U.S. government suggests that Engeln’s hats and ties would have cost $255.86 and $102.34, respectively, in December 2022.

52 Harry Borba, “Side Lines,” San Francisco Examiner, May 13, 1945: 16.

53 “O’Doul Honored by Trader Vic’s on Occasion of 49th Birthday,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, March 5, 1946: 13.

54 “Seals, Hawaii Stars Ready to Put On Hot Opener Friday Night,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, March 5, 1946: 12.

55 Harry Borba, “Seals’ Plane Turns Back,” San Francisco Examiner, March 26, 1946: 20; “Some Delayed Seals, Scribes May Go Today,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, March 26, 1946: 13.

56 More detail on Rowland’s effort can be read in Warren Corbett, “Pants Rowland,” SABR Biography Project, accessed January 15, 2023.

57 The Sporting News, October 30, 1946: Supplement B: 3. (Online searchers will find the ad on page 75 of the electronic version.)

58 Alan Ward, “On Second Thought,” Oakland Tribune, July 18, 1949: 18.

59 Harry Borba, “Side Lines,” San Francisco Examiner, December 23, 1948: 24.

60 Sid Ziff, “The Inside Track,” Los Angeles Mirror, February 6, 1951: 52.

61 Associated Press, “N.L. Prexy Fines Robb After Cards’ Rhubarb,” South Bend (Indiana) Tribune, April 24, 1952: 2: 3.

62 United Press, “Scotty Robb Resigns as Ump Because of Stanky Incident,” Knoxville (Tennessee) News-Sentinel, May 6, 1952: 15. Robb was hired by the AL for the 1953 season, but worked only through June 28 before leaving the majors for good.

63 “National League Buys Contract of Bill Engeln, PCL Umpire,” Sacramento Bee, May 19, 1952: 26.

64 Alan Ward, “On Second Thought,” Oakland Tribune, May 23, 1952: 42.

65 Emmons Byrne, “The Bull Pen,” Oakland Tribune, May 22, 1952: 25.

66 Dana Mozley, “Cubs Tally 9 Runs in 7th to Defeat Giants, 11-8,” New York Daily News, August 1, 1952: 51; Associated Press, “Sal Yvars Fined $100 for Dispute with Ump,” Arizona Republic (Phoenix, Arizona), August 3, 1952: 2: 2.

67 George Beahon, “Toporcer Remains After Game for Press Box Serenade” and “Specs’ Share from Benefit Game Expected to Exceed $15,000,” Rochester (New York) Democrat and Chronicle, July 22, 1952: 26.

68 An interesting side note: Engeln was known in baseball as “Pa Kettle,” a nickname reportedly given him by Hollywood manager Fred Haney during Engeln’s time in the PCL. Pa Kettle was a country rube character, kindly but lazy, played in a series of comic movies by actor Percy Kilbride. News references do not explain how Engeln got the name. It was certainly not because the scholarly, dapper Engeln reminded anyone of a hayseed. More likely, it was simply because Engeln’s long, lean face resembled that of Kilbride/Kettle. Appearances of the nickname in print include Les Biederman, “The Scoreboard,” Pittsburgh Press, July 31, 1954: 6; Jack Hernon, “Roamin’ Around,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, June 21, 1956: 21; and “By Dick Anderson,” Evansville (Indiana) Press, August 7, 1956: 16.

69 Robert E. Hannon and Sam Caldwell, “They Walk Alone,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 10, 1952: Pictures section: 6-7. Engeln’s age is listed as 48 in one photo caption.

70 “Picture Story,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 15, 1953: 25.

71 John Saccoman, “Carl Furillo,” SABR Biography Project, accessed January 15, 2023; Associated Press photo and caption of brawl, Lewiston (Maine) Daily Sun, September 7, 1953: 8.

72 Art Knight, “Sports of the Times,” San Mateo (California) Times, January 28, 1953: 26; Walt Gamage, “Sport Shots,” Palo Alto (California) Times, July 16, 1953: 20.

73 Walter Judge, “Engeln Urges Pay Hike for Umpires in PC Loop,” San Francisco Examiner, February 3, 1954: 26.

74 Lupi Saldana, “PCL Ump Row Mushrooms,” Los Angeles Daily News, February 5, 1954: 34.

75 “Diamond Dust: Dodgers,” New York Daily News, April 16, 1954: 48; Dick Young, “The Sports of Kings and Queens,” New York Daily News, April 18, 1954: 17B.

76 This was Engeln’s only major-league no-hitter. He had umped behind the plate for at least one no-hitter in the PCL, pitched by Joe Demoran of the Seattle Rainiers in 1946. Associated Press, “Seattle Pitcher Hurls No-Hitter,” Casper (Wyoming) Tribune-Herald, April 5, 1946: 11.

77 Photo and caption, New York Daily News, August 2, 1954: 40.

78 Associated Press, “Batters, Too, Delay Games, Says Umpire,” Portland (Maine) Press Herald, January 26, 1955: 12.

79 Bob Wood, “Sports Splinters,” Uniontown (Pennsylvania) Morning Herald, March 9, 1955: 12.

80 “Top Sport Thrills for ‘55 By,” Palo Alto Times, December 26, 1955: 14.

81 The 1955 All-Star Game was played on July 12. According to Retrosheet, Engeln worked five games at New York’s Polo Grounds leading up to the break, and a two-game series in Philadelphia coming out of it.

82 Curley Grieve, “Sports Parade,” San Francisco Examiner, August 3, 1947: 25.

83 Curley Grieve, “Sports Parade,” San Francisco Examiner, February 18, 1955: 29. Coincidentally, Engeln’s last day in the major leagues – September 30, 1956 – was also Shepard’s, as the young catcher unexpectedly retired to take a development position with his alma mater. Jack Zerby, “Jack Shepard,” SABR Biography Project, accessed January 15, 2023.

84 Dave Wik, “Umpiring in Major Leagues Is No Soft Touch,” Palo Alto Times, February 16, 1956: 11. Engeln’s complaint about his itinerary was reprinted in Jack Hernon, “Roamin’ Around,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 16, 1956: 23.

85 Engeln’s six ejections in 1956 were the most of any of his five seasons in the majors; whether that had anything to do with the broader dissatisfaction among NL umps is a matter of conjecture.

86 Jim McCulley, “Action in Pitt,” New York Daily News, July 2, 1956: C22.

87 Jimmy Powers, “The Powerhouse,” New York Daily News, June 12, 1956: 59.

88 United Press, “Two New Umpires Appointed by NL,” Pittsburgh Press, December 20, 1956: 26; Associated Press, “National League Buys Two Umpires,” Corsicana (Texas) Daily Sun, December 20, 1956: 4.

89 Harold Kaese, “Camera Vindicated Gore on Close Play in ‘53 Series,” Boston Globe, December 21, 1956: 18; Jerry Nason, “Was Umpire Artie Gore ‘Robb-ed’?,” Boston Globe, December 23, 1956: 11.

90 Ritter Collett, “Journal of Sports,” Dayton (Ohio) Journal Herald, December 21, 1956: 44.

91 Jim McCulley, “One Man’s Opinion,” New York Daily News, December 24, 1956: C22.

92 Goetz’s comments followed the firing of ump Frank Dascoli, who made similar comments about Giles allegedly forcing NL umpires out the door. Harry Grayson, “Easier for Giles to Fire Umpires than Back Them Up, Says Goetz,” Wilmington (Delaware) Evening Journal, August 14, 1961: 22.

93 Walt Gamage, “Sport Shots,” Palo Alto Times, June 25, 1957: 16; United Press International, “Baseball Will Die if Umps Get Gate,” Zanesville (Ohio) Times Recorder, May 14, 1963: B2.

94 Wilbur Adams, “Between the Sport Lines,” Sacramento Bee, February 28, 1957: D1.

95 “Gordon Ford Is Released by PCL,” San Francisco Examiner, February 27, 1957: II: 4.

96 Gamage, “Sport Shots,” Palo Alto Times, June 25, 1957.

97 “Baseball Will Die if Umps Get Gate.”

98 “Area Fans Jubilant Over Move,” Palo Alto Times, August 20, 1957: 14; Gamage, “Sport Shots,” Palo Alto Times, June 25, 1957.

99 The 1968 A’s opened their season with five games on the road.

100 “Death Claims Bill Engeln, Former Umpire,” Palo Alto (California) Times, April 18, 1968: 31; “W.R. Engeln,” Palo Alto Times, April 19, 1968: 4. Engeln’s gravestone bears his correct birth year, 1898. Incidentally, Engeln’s entire clipping file at the Giamatti Research Center of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum consists of his Sporting News obituary and a subsequent letter from a reader. Author’s correspondence with the Giamatti Research Center, January 2023.

101 A death listing in a Washington newspaper requested that memorial donations be given to a local church. “Engeln” (death listing), Palo Alto Times, April 19, 1968: 4; “Engeln, William R.” (death listing), Spokane (Washington) Spokesman-Review, April 20, 1968: 15.

Full Name

William Raymond Engeln

Born

September 9, 1898 at St. Louis, MO (US)

Died

April 17, 1968 at Palo Alto, CA (US)

Stats

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.