Bob Chance

Bob Chance – a lefty-hitting, righty-throwing right fielder and first baseman – played on three major-league teams in six seasons in the 1960s. At 6-foot-2, Chance was big and powerful. Gripping the bat with his right palm wrapped around the knob of the bat, he hit colossal home runs, some of which allegedly traveled over 500 feet.1

Bob Chance – a lefty-hitting, righty-throwing right fielder and first baseman – played on three major-league teams in six seasons in the 1960s. At 6-foot-2, Chance was big and powerful. Gripping the bat with his right palm wrapped around the knob of the bat, he hit colossal home runs, some of which allegedly traveled over 500 feet.1

Chance was an outstanding minor-league player who never achieved his potential in the majors – not unlike hundreds of others whose skills came up short or whose advancement was blocked by better players. When he played regularly in the minors and in Japan, he batted .300, but when he platooned in the major leagues, he batted .261.

Chance’s most publicized nemesis was his weight. He weighed 196 pounds when he signed his first contract – but bulked up to 222 pounds or more in the seasons that followed. Chance’s weight reduced his standing with his employers, limited the number of positions he could play, and therefore curtailed his playing time in the big leagues.

However, perhaps underestimated was that Chance played his entire US professional career in the 1960s – a decade marked by unregulated mound height and declining offensive production, an upsurge in the number of games played under the lights, and wary racial integration.2 Those complicated dynamics may have contributed, at least in part, to knocking Chance’s promising major-league career off course.

* * *

Robert Chance was born on July 10, 1940,3 in Statesboro, Georgia, in agrarian Bulloch County. His father was Willie Chance, a farmer and laborer who had no formal schooling. His mother, Rosa Lee (whose maiden name was also Chance), was a housekeeper who attended school until fourth grade. Robert was their only child.

Chance attended William James High School, an all-Black school of about 160 students where the girls outnumbered the boys by more than two to one and where more than 50 percent of the students in Chance’s 1958-59 senior class, including him, were members of the 4-H Club. Chance played football and basketball; he played baseball in the sandlots and Sunday leagues because his high school did not have a baseball program.4 Music was his hobby.

Soon after his graduation, Chance connected with Herman Mincey, whose family was from Statesboro. Mincey managed a semipro team called the Jersey City Cubs in Hudson County, New Jersey, and he invited Chance to come north. Hudson County was a fertile source of major-leaguers, including Chance’s future teammates, John Romano and Jim Hannan. Mincey gave Chance a room in his house so that he could play for the Cubs.5

Chance was invited to try out before a panel of scouts at Jersey City’s Roosevelt Stadium on July 11, 1960.6 To be sure not to lose the hot prospect, however, San Francisco Giants scouts Fred Meyer and Frank (“Chick”) Genovese signed Chance on July 9.7 “I got nothin,’” said Chance – that is, no bonus.8 Although Chance pitched for the Cubs, he was signed as an outfielder.

In 1961 he and future major-leaguers José Cardenal and Dick Dietz led the El Paso (Texas) Sun Kings (Class D) to a 73-57 record under manager George Genovese (Chick’s older brother). In his first at-bat he hit a pinch-hit grand slam.9 Chance hit .371, second best in the Sophomore League, with 16 home runs and 96 runs batted in, and was named to the league’s All-Star team.

Meanwhile, up in the American League, Frank Lane succeeded Hank Greenberg as Cleveland’s general manager in 1958. For years, the team struggled to win games, to attract fans, and to remain in Cleveland. “Trader Frank’s” three years there featured a constant turnover of managers and players. Every year, it seemed, he and his successor Gabe Paul turned to somebody new to try to reverse the team’s fortunes: Rocky Colavito (1955-59, 1965-67), Vic Power (1958), Harvey Kuenn (1960), Tommie Agee (1962). The Tribe had their eye on Chance as the next great hope after they lost outfielders Marty Keough and Jim King in the December 1960 expansion draft.

Cleveland selected Chance in the 1961 first-year player draft. Chance was not unhappy: “I knew I’d never make the Giants,” he admitted. “Not with players like Mays, McCovey and the Alous in the outfield.”10

Chance played well in the Carolina League (Class B) and the Eastern League (Class A) in 1962. In 1963, he played for the Charleston (West Virginia) Indians, who came in first place in the Eastern League in its first year as a Class AA circuit. In Charleston, Chance met his wife-to-be, Carrie Lou Hall, daughter of tradesman and city employee Lewis Hall and his wife Helen. Carrie – one of five Hall children – was a chorus singer in, and 1963 graduate of, Charleston High School.

On the field, he led the league – normally a “pitching paradise”11 – in 10 offensive categories, including batting average (.343), home runs (26), and runs batted in (114).12 His Triple Crown was the first one in the EL since 1925.13 Chance was voted unanimously to the league’s All-Star team. He was also selected as Topps’ Eastern League Player of the Year – and was promoted to the big leagues when rosters expanded.

On September 4, 1963, Chance debuted against Hall of Famer Robin Roberts and went 0-for-3 with two strikeouts. With his debut jitters behind him, he got 13 hits, two home runs, and six RBIs in his next nine games before he cooled off.

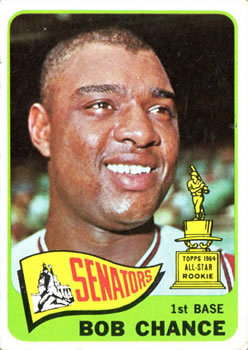

Chance enjoyed a fine rookie season with the Indians in 1964 – his best in the big leagues. He was among the team leaders with a .279 batting average (first place on the team), .346 on-base percentage (tied for first), 75 RBIs and .780 OPS (second), and 14 home runs (fifth) despite wrenching his knee and becoming a pinch-hitter for most of the end of the season. Chance was named to the Topps All-Star Rookie Team.

Interim manager George Strickland had this to say: “He’s so strong, that he can be fooled on a pitch and still knock it out of the park.”14 Coach Solly Hemus added, “He has a beautiful, natural swing.”15

Manager Birdie Tebbetts piled on more praise: “Strick and Solly did wonders with him, but this kid really wanted to play ball or he wouldn’t have worked so hard and so willingly.”16

Chance had plenty of highlights during that rookie season. In June he had an eight-game hitting streak during which he went 13-for-25, raising his average to .421, with four home runs and seven RBIs. On June 7, 1964, Chance hit two home runs, one off a lefty pitcher and one off a righty, in a 3-2 win over the Washington Senators. On July 10 – his 24th birthday – he helped defeat the first-place Baltimore Orioles with two home runs and five RBIs.17 Eight days later against the Detroit Tigers, he knocked in three runs, including the game-winner, without a hit (two ground ball outs and a sacrifice fly).18

On Friday, July 24, 1964, Chance married Carrie in a private ceremony. After the rite, Chance dashed to Cleveland Stadium in time for the game against Boston. He collected two hits and knocked in four runs to help the Indians defeat the Red Sox, 6-1.19

Chance hit well against both lefties and righties, especially with men on base. RBIs were his specialty. In 1964, in 390 at-bats, Chance knocked in 75 runs – a rate of one batted in for every 5.20 official at-bats. (His roommate and best friend on the team, Leon Wagner, led the club in ’64 with 100 RBIs at the rate of one ribbie every 6.41 at-bats.) Chance remained clutch with men on base throughout his major-league career – 6.67 at-bats for each RBI.20 In the minors he was even better. In his big year at Charleston in 1963, he had an RBI every 4.7 at-bats. And later (1965-68) when he was in the Washington Senators’ Triple-A farm system, he had a 6.1 AB/RBI rate. In Japan (1969-70), Chance’s rate was 6.2.

In the ’60s, the strike zone got bigger and home runs got fewer. With the drop-off of the home run came the resurgence of the running game. In 1964 the Indians led the American League with 79 stolen bases. Stealing bases was not part of the big fella’s arsenal. Yet, Chance did surprise the defense on three occasions in 1964 to collect his only steals in the majors.21

Another hallmark of baseball in the ’60s was the increased number of night names – in which Chance did not bat well. Over his major-league career, he batted .288 in day games (115-for-400) but only .231 in night games (80-for-347). Fifteen times in his career, he had three or more hits in a game – nine with the Indians and six later with the Senators. Thirteen of those were day games.

Equally interesting, Chance struck out three or more times in seven games in his career. Six of those were night games; on the seventh occasion the game started at 5:02 p.m. as the opener of a twi-night doubleheader – the shadows at Baltimore’s Memorial Stadium arrived soon after the game started.

All in all, 1964 was the high point of Chance’s career. However, on December 1, 1964, he and utilityman Woodie Held were traded to the Washington Senators for Chuck Hinton, a popular and versatile player, an original selectee of the expansion Senators in 1960, and in 1964, the first Senator to be voted, not placed, onto the All-Star team. Washington had become concerned with Hinton’s health after he was beaned by Yankees pitcher Ralph Terry in 1963 and suffered a knee injury in 1964. On the other side of the deal, the Indians were unhappy that Chance arrived in camp that spring 25 pounds overweight, and they had slugger Fred Whitfield in the wings ready to play first base full time.

Yet, at 24, Chance still appeared to have a big future ahead of him. Indians manager Tebbetts said: “We’re glad to get [Hinton] – make no mistake – but we sure did give up a lot of talent for him.”22

At first the deal appeared to be promising for Chance, with Gil Hodges, the former slugger and three-time Gold Glover, to manage Chance’s further development both at the plate and in the field. Hodges told the fans, “He’s the kind of hitter who could wind up leading the league.”23 Instead, Chance’s stretch with the Senators was far from rewarding.

Chance started well in 1965, batting .283 in April, but in May his offense had slipped. Just before the All-Star break, he was assigned to the organization’s new Triple-A club in Hawaii (Pacific Coast League). Chance’s replacement at first base, Dick Nen, had come to the Senators with Frank Howard as part of a seven-player deal three days after Chance was acquired. Nen may have been a better defensive player, but he did not fare much better at the plate in the second half than Chance did in the first half. Chance’s consolation was that the Islanders finished with a better record than the Senators.

Chance came north to open with the Senators in each of the next two seasons, but he did not make it out of June in 1966 or May in 1967 before being demoted to the Hawaii Islanders again. There were some good moments, such as a pinch-hit grand slam on April 17, 1966. He also hit three homers in 1967, one to help the Senators defeat the Angels three days before he was sent down and another – a three-run pinch-hit shot – after he came back up. None of these, however, earned Chance any regular playing time.

Several factors can be considered, but no clear answer emerges for Chance’s struggles in Washington. The predictable guesses of age and injury are ruled out. Chance was only 25 years old in 1965 and had suffered only two minor injuries up to that point. He hurt a knee in winter ball in Puerto Rico but started the 1965 season on time.24 His left wrist was broken by a pitch in Hawaii on July 26, 1965, but although it was first feared that he would miss the remainder of the season, he hit a game-winning, two-run pinch-hit single in his first game back with the Senators on September 2, 1965, and he finished the season with a 10-for-20 burst.25

Chance played first base regularly in Hawaii and provided a productive bat in the heart of the order in 173 games for six months over the 1966 and 1967 seasons. In a weekend series against the Denver Bears in August 1967, he hit game-winning homers on three consecutive nights.26 He was in his prime and could still play. Yet, Hodges lost his confidence in Chance. Before the 1967 season began, the skipper shifted from “Chance could lead the league” to “Bob Chance and Dick Nen will have to hit more to make the grade.”27

Chance’s most confounding season was 1968. One of the last to be cut before the team headed north, Chance was assigned to the Senators’ new Triple-A club, the Buffalo Bisons in the International League. The Senators had acquired minor-league phenom and first baseman Mike Epstein in May 1967. His managers – Hodges in 1967 and Jim Lemon in 1968 – stuck with Epstein even as he struggled.

Chance tore the cover off the ball in Buffalo in 1968. He finished fourth in the league in hits (149), third in home runs (29), and second in RBIs (84). The gentle giant batted .293 with an .862 OPS (well above the league average of .252 and .689 in those two categories), led the Bisons in doubles, total bases, and runs scored, and was selected to the International League All-Star team. Yet, he was not promoted.

Perhaps when the Senators sent Chance to Buffalo, they sought to echo Steve Bilko’s history. Bilko was a hefty but popular slugger who was signed by the St. Louis Cardinals in 1945 and traded to the Chicago Cubs in 1954. When he failed to stick in the majors, Bilko was sent to the California Angels in the Pacific Coast League. There, management employed a “hands off policy” with regard to Bilko’s weight and “Stout Steve” responded with three consecutive MVP seasons in the PCL. Bilko’s minor-league success brought opportunities with four more major-league teams before he retired.28

That was not the way it worked out for Chance. Even with Nen’s departure in April and Epstein’s demotion on May 23 (he was batting .099 at the time), Chance never saw time with the Senators. Instead, left fielder Frank Howard began playing more first base, logging 55 games there in 1968 as compared to four in 1967 and 1966 combined. Rookies Brant Alyea (.267 BA and .790 OPS) and Del Unser (.230 BA and .560 OPS) were promoted to patrol left field and center, respectively. Perhaps there was some other dynamic at play in the Capital City.

When Jim Lemon became manager in 1968, he told the press that he was looking specifically for “catching help, a centerfielder who can catch a ball and probably a second baseman.”29 The first declaration seemed curious because Washington already had 1967 All-Star Paul Casanova at catcher. The promotion of Unser and Alyea and the retention of Ed Stroud (.239 BA and .660 OPS) made it clear that the Senators had no plans to move Chance to the outfield. Frank Coggins started the season at second base until he and outfielder Sam Bowens were sent down to Buffalo midseason. Hank Allen (.219 BA and .554 OPS) was a utility player for Lemon most of the season. Outfielder Fred Valentine was traded away in June.

Normally a man of few words, Chance allowed his frustration to bubble up. “Sure, you compare my statistics to Frank Howard’s and they’re not much. Compare them to the other Washington players and they’re better.”30

It was not until April 1969 that the public got a glimpse of what went on in the Senators’ organization in 1968. By that time Chance was no longer with the team.

The 1960s was no ordinary time for African Americans – not in baseball, not in America, not in the District of Columbia. Washington, DC, was scarred by a series of race-related events. To start with, the Washington Redskins finally agreed to desegregate in 1961 – the final franchise in the National Football League to do so. Then came the exodus to Minnesota of Calvin Griffith’s baseball Senators in 1961 – a move which later was disclosed to be racially motivated.31 Finally, the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4, 1968 sparked four straight days of rioting.

On December 3, 1968, trucking and hotel baron Bob Short purchased the Senators from James Lemon (no relation to manager Jim Lemon). The article that shook Chance and others was published on April 24, 1969, in JET magazine. The article was titled “More Blacks Will Wear Nats Uniform, Says New Owner.”

The suspicion widely held at the time – and confirmed years later in several sources – was that an unwritten agreement existed among many owners, mostly in the AL, to cap the number of African Americans on a team.32 But Short told JET, “As long as I’m in charge, this will be a color-blind franchise.”33

His comments came in response to Hank Allen’s assertion that, “We [Casanova, Allen, and Stroud] were very uncomfortable last year. We didn’t get a fair chance to play, and all three of us sensed we were not wanted here.”34

At the end of the 1968 season, one of James Lemon’s and GM George Selkirk’s last administrative moves was to leave Chance unprotected for the postseason drafts. On December 2, 1968, the California Angels, who’d lost starting first baseman Don Mincher in the 1968 expansion draft, drafted Chance in the Rule V draft.

Chance’s wife Carrie was happy to leave Buffalo for Los Angeles. Chance was not as thrilled. He tipped the scale at 234 pounds when he arrived at spring camp in 1969, and the Angels’ brass noticed.35 In April, impressed by the 49 home runs that free agent first baseman Dick Stuart had hit over the previous two years in Japan, the Angels signed the 36-year-old Stuart to start the season until the Texas League’s 1968 Player of the Year Jim Spencer was ready for The Show in May. Chance started the season on the bench.

In his first at-bat for the Halos, Chance singled home a run. However, he struck out in four of his next six at-bats (three of the strikeouts were in a night game, by the way). On April 30, 1969, California traded Chance to the Atlanta Braves – finally, a contending team. Yet, Chance’s way was again blocked, this time by Orlando Cepeda.

The Braves may have acquired Chance as insurance following the tumult that surrounded the Joe Torre-for-Cepeda trade with the St. Louis Cardinals a month earlier. Paul Richards had a running feud with Torre, Atlanta’s player representative. The sulky Cepeda felt he was a consolation prize after Atlanta’s effort to deal Torre to the New York Mets fell through.

“Atlanta. St. Louis. It doesn’t matter,” said Cepeda.36

Chance did not play one game with Atlanta; he was assigned to their Triple-A affiliate in Richmond, Virginia – another cellar-dwelling club. He never got the chance to take advantage of the majors’ smaller strike zone and lower mound, introduced that season in reaction to the 1968 “Year of the Pitcher.” Richmond released Chance after 56 games, and he was on the move again for the third time in seven months – this time to Japan.

Chance had a teammate on the Indians, the Senators, and the Hawaii Islanders named Willie Kirkland. In 1967, Kirkland led the Islanders with 34 home runs and 97 RBIs; yet, like Chance a year later, Kirkland did not play a single game with the Senators that year. Kirkland left the United States and played for the Hanshin Tigers in the Japan Central League, where he played for the next six seasons.37

Chance’s second connection with Japan was Walter Brock, the farm director for the Cleveland Indians before he became Selkirk’s assistant with the Senators in 1962. By 1968 Brock was an independent baseball consultant and sports entrepreneur, and he served as a goodwill liaison between US talent and the Sankei Atoms. Brock had helped place Dave Roberts and Lou Jackson, African American sluggers with brief major-league experience, with the Atoms.38 When Jackson died suddenly from pancreatitis on May 27, 1969, Brock contacted Chance, who jumped at the opportunity with shoshin – Japanese for “a beginner’s mind.”

On August 1, 1969, the growing Chance family – Bob and Carrie and their two young children, Anthony and Samantha – arrived in Tokyo. Three days later, the freshly minted gaijin (“foreign player”) hit two home runs, one in each game of a doubleheader. The Japanese press embraced the newcomer as “this hulk of a man with strong arms and soft voice, a ‘Silent Monster.’”39

Chance dazzled his new teammates with his .320 batting average and 1.022 OPS. Those marks were second-best in the league that year – only the great Sadaharu Oh, the Central League MVP that year, did better.

To fill the time when Chance traveled with his club,40 Carrie again found work as a model, the profession she pursued both in Maryland and Niagara Falls. In Japan, even their children took turns in front of the camera.41

In 1970, despite getting more at-bats, Chance had fewer hits, home runs, RBIs, and runs with the Atoms than he did the year before. After 10 seasons in pro ball, the time had come for Chance to retire. According to some accounts, his retirement was hastened by bad knees.42 He was 30 years old.

Chance’s final move was a return to Carrie’s hometown of Charleston, West Virginia. There he worked first for the City of Charleston Department of Recreation43 and then for the North Carolina Alcoholic Beverage Control Commission.44 Carrie worked as a staff associate in the Federal-State Relations office at City Hall.45 Chance also coached the Charleston basketball team in the Junior Pro League. In 1973, Carrie gave birth to their third child, Marlow. Chance lived in Charleston for 43 years.

Bob Chance died of complications from prostate cancer on October 3, 2013, at age 73 – eight years after Carrie died at the age of 60. He was survived by their three children, another son (Cecil), and six grandchildren.46 The couple are buried in Sunset Memorial Park in Charleston.

After Chance’s death, his son Anthony told The Jersey Journal:

“My dad was kind of a quiet man. He really didn’t talk a lot about his accolades or him playing baseball unless you really probed him about it. . . . [H]e kept a close tab on the Indians. That was his team. That was near and dear to him. . . .”47

Postscript

Robert Anthony “Tony” Chance – Bob and Carrie’s oldest child – grew up in Charleston and attended Charleston High School. The fleet, righty-hitting outfielder signed with the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1983 and eventually became one of the organization’s better prospects. Tony had his best season at Class A in 1987, leading the Carolina League in hits and total bases. He was named to the league’s All-Star team and his Salem Buccaneers won the pennant.

After seven seasons in the Pirates’ system, Tony was traded in June 1989. He bounced around the high minors, the Mexican League, Taiwan’s Chinese Professional Baseball League, and independent circuits for 13 years more; he never played in the majors. He finally retired from baseball in 2002 at age 37.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Bruce Harris and fact-checked by Paul Proia.

Special thanks to Cassidy Lent, manager of reference services at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, for supplying copies of news clippings from the files in Cooperstown.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted sabr.org, baseball-reference.com, retrosheet.org, newspapers.com, ancestry.com, facebook.com, and deanscards.com.

Notes

1 In Reading, Pennsylvania (Eastern League), Ed Connolly saw Chance hit a home run “that went a ridiculous distance. They estimated it at 570 feet. It cleared the light towers, roads behind the park, and everything.” See Roger O’Gara, “Fair or Foul,” The Berkshire Eagle (Pittsfield, Massachusetts), September 27, 1963: 13. Near the end of his career, “Bob Chance with Buffalo in ’68, hit one [farther than 484-feet] that was as high as the light tower as it sailed over the right field barrier.” See Ron Coons, “Oglivie Hits ‘Record’ 484-foot Homer,” The Courier-Journal (Louisville, Kentucky), July 26, 1971: B-7.

2 Twenty years after Jackie Robinson Jr. broke the color line, several teams, especially in the American League, were still slow to add African American players. Historians noted years later that those who did play in the Sixties had to be “superior.” See Arthur R. Ashe Jr., A Hard Road to Glory–Baseball: The African-American Athlete in Baseball (New York: Amistad Press, 1993): 56.

3 See https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/146623135/bob-chance; “Bob Chance,” Washington Senators 1965 Media Guide: 14; Bob Chance’s Player Questionnaire; and The Sporting News Baseball Player Contract Card. However, several on-line reference sources including baseball-reference.com, baseball-almanac.com, and statscrew.com give September 10, 1940, as Chance’s birth date, perhaps a typo somewhere along the line misidentifying a “7” (for July) as a “9” (for September). Finally, for the 1940 US Census, the enumerator visited the house in April, 1940. Bobby Joe Chance is already listed as a half year old on the census record, raising a question of whether Chance was born in 1939.

4 School information was obtained from The 1959 Jamesonian, the high school yearbook, accessed through ancestry.com. Bulloch County schools were not fully desegregated until 1971, 17 years after Brown v. Board of Education, the landmark Supreme Court decision which held that segregated public schools were unconstitutional.

5 Patrick Villanova, “Bob Chance, a Major Leaguer, at 73; Launched Career in Jersey City,” The Jersey (Jersey City, New Jersey) Journal, https://www.nj.com/jjournal-news/2013/10/bob_chance_a_major_leaguer_at.html, posted October 9, 2013, updated January 17, 2019, accessed February 12, 2024.

6 “Met’s Top Baseball Players Get Major League Tryouts Monday Morning,” The Jersey (Jersey City, New Jersey) Journal, July 9, 1960: 10.

7 “Jersey City’s Chance Signs Giants’ Pact,” The Jersey (Jersey City, New Jersey) Journal, July 11, 1960: 18.

8 Regis McAuley, “Indians Took Big Chance – Bob’s Bat Provides Payoff,” [name of newspaper unknown], June 20, 1964. (Article provided courtesy of National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.)

9 Larry Babich, “Giants’ Gamble on Chance Paying Off,” The Jersey (Jersey City, New Jersey) Journal, September 14, 1961: 16.

10 Larry Babich, “Hodges Rates Chance Potential Bat King,” The Jersey (Jersey City, New Jersey) Journal, June 3, 1965: 30.

11 Ferd Borsch, “Chance to Fatten HR Punch,” The Honolulu Star Bulletin, July 18, 1965: C-4.

12 In addition to BA, HRs and RBIs, Chance was number one in the league in hits, walks, doubles, total bases, on-base percentage, slugging average, and on-base plus slugging.

13 Roger O’Gara, “Fair or Foul,” The Berkshire Eagle (Pittsfield, Massachusetts), September 27, 1963: 13.

14 Harry Jones, “Bob Chance Is Writing Comeback Classic,” News-Herald (Willoughby, Ohio), June 12, 1964: 13.

15 Associated Press, “Chance Celebrates Birthday in Style,” The Sandusky (Ohio) Register, July 11, 1964: 11.

16 “Hat’s Off,” The Sporting News, August 8, 1964: 25. Further testimony to Chance’s willingness to work hard at the game he loved is the fact that he played winter league ball in 1963-64 and 1964-65 in Puerto Rico, 1966-67 in Nicaragua, and 1968-69 in Venezuela [based on information available at this time].

17 Associated Press, “Chance Celebrates Birthday in Style.”

18 On April 3, 2024, in a game against the Seattle Mariners in Seattle, Josh Naylor became the second player in franchise history to knock in three runs without a hit (one ground ball out and two sacrifice flies).

19 Associated Press, “Yesterday’s Stars,” Iola (Kansas) Register, July 25, 1964: 6. See also, “Hat’s Off,” The Sporting News, August 8, 1964: 25.

20 How did Chance’s 6.67 clutch RBI rate and .261 lifetime MLB batting average compare to the first basemen who blocked his advancement? According to www.baseball-reference.com, Fred Whitfield’s major-league career rate was 6.42 at-bats per RBI with a .253 BA, Dick Nen’s was 7.72 and .224, Mike Epstein’s was 7.51 and .244, and Jim Spencer’s was 8.19 and .250.

21 Chance’s stolen base record is intriguing, actually. The big man stole 11 bases and was caught only three times during his years in the minor leagues before his major-league debut. With Cleveland in 1964, he swiped his first base with confidence in May, before getting thrown out three straight times in June. Undaunted, he stole two more bases that summer. Chance stole once more, with the Hawaii Islanders (Triple-A) while getting thrown out three times, from 1965–1969. When he played in Japan, he stole three bases in 1970 at age 29, with one caught stealing.

22 United Press International, “Tribe Obtains Hinton in Three-Player Swap,” The Raleigh (Beckley, West Virginia) Register, December 1, 1964: 10.

23 Larry Babich, “Hodges Rates Chance Potential Bat King,” The Jersey (Jersey City, New Jersey) Journal, June 3, 1965: 30.

24 Associated Press, “Bob Chance Makes Debut with Senators,” The San Bernardino County (California) Sun, March 1, 1965: A-17.

25 “Islanders Lose Chance for Remainder of Season,” The Honolulu Star Bulletin, July 28, 1965: E-5.

26 David Lamb, “Portland Sweeps PCL Bill,” The Times Standard (Eureka, California), August 14, 1967: 20.

27 Associated Press, “Gil Hodges May Shift Frank Howard to First,” The Roanoke (Virginia) Times, January 17, 1967: 20.

28 Gary Joseph Cieradkowski, “Steve Bilko: The Legend of Stout Steve,” https://studiogaryc.com/2022/08/27/steve-bilko/, August 22, 2022, accessed February 27, 2024.

29 Associated Press, “Jim Lemon Welcomes New Washington Job,” The Anderson (Indiana) Herald, January 9, 1968: 9.

30 Ross Newhan, “Angels’ Chance Sweats Out Last Chance at Job,” Los Angeles Times, March 18, 1969: Part III-1.

31 In an after-dinner speech in Minnesota in 1978, Griffiths divulged that the real reason he moved the team was that the fan base in the Minneapolis-St. Paul area had a much greater white demographic than D.C. had: “Black people don’t go to ballgames,” he said. See also Brad Snyder, Beyond the Shadow of the Senators: The Untold Story of the Homestead Grays and the Integration of Baseball (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2003), 289.

32 See, e.g., Chuck Hinton, My Time at Bat: A Story of Perseverance (Largo, Maryland: Christian Living Books, 2002), Kindle, Chap. 11.

33 “More Blacks Will Wear Nats Uniform, Says New Owner,” JET Magazine, April 24, 1969: 54-55.

34 “More Blacks Will Wear Nats Uniform.” This revelation from Allen makes the “pleasant problem” remark from Selkirk in the 1968 preseason about his African American players more intriguing: “Take Sam Bowens – the fellow we bought from Baltimore. My problem is where he will be played. . . . Will he push Cap Peterson out of right field? Will Hank Allen be able to hold off Del Unser in center? And how about Fred Valentine?. . . I’m not forgetting Ed Stroud, who has experience and can run.” Bob Addie, “Nats to Wipe Out Howard’s Pay Cut,” The Sporting News, January 27, 1968: 34.

35 Newhan, “Angels’ Chance Sweats Out Last Chance at Job,” Part III-1, 4.

36 Frank Dolson, “Touch of Sorrow Brushes This Good-By,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, March 20,1969: 43.

37 In 1969, seven African Americans, one Panamanian, one Bahamian, and one Puerto Rican filled 10 of the possible 24 gaijin spots available on the 12 teams in the two Japanese leagues (a maximum of two per team). The players were: Chance and Roberts, Sankei Atoms; Kirkland and Joe Gaines, Hanshin Tigers; Stan Johnson and André Rodgers, Taiyo Whales; Carl Boles and Aaron Pointer, Nishitetsu Lions; George Altman and Art López, Lotte Orions.

38 See Elton Case, “Brock Back from Japan,” The Herald-Sun (Durham, North Carolina), January 8, 1970:1B, and Tom Kelly, “Long Road to Travel for Bayfront Hockey,” St. Petersburg (Florida) Times, May 30, 1971: 3-C.

39 Jerry Lindquist, “Rain Halts R-Braves, Bisons,” Richmond (Virginia) Times-Dispatch, August 10, 1969: F-1, F-2.

40 In Japan, games are played not only where the league’s teams are located but in other cities as well. See Robert F. Hemphill, “Baseball in Japan Has Flavor,” The Kansas City Times, October 1, 1970: 6B.

41 Rosalie Earle, “City Hall Worker Also Wife, Mother, Part-Time Model,” The Charleston (West Virginia) Gazette, October 11, 1975: 12A.

42 See, e.g., Christine Krapf, “Sons of Ex-Big Leaguers Dot Carolina League,” The News & Daily Advance (Lynchburg, Virginia), August 10, 1988: C-4.

43 Earle, “City Hall Worker Also Wife, Mother, Part-Time Model,” 12A.

44 Larry Babich, “Twilight League Was Chance of a Lifetime,” The Jersey (Jersey City, New Jersey) Journal, May 23, 1997: C1, C3.

45 Earle, “City Hall Worker Also Wife, Mother, Part-Time Model,” 12A.

46 Villanova, “Bob Chance, a Major Leaguer, at 73; Launched Career in Jersey City.”

47 Villanova.

Full Name

Robert Chance

Born

September 10, 1940 at Statesboro, GA (USA)

Died

October 3, 2013 at Charleston, WV (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.