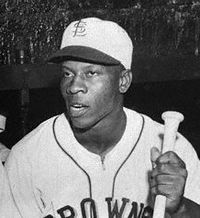

Willard Brown

Ese Hombre — That Man — was Willard Brown’s nickname in Puerto Rico. The outfielder was one of the most feared hitters in the Negro Leagues, but he was an absolute wrecking ball in the Puerto Rican Winter League. He won the Triple Crown twice there, in 1947-48 and 1949-50. Unfortunately, he played just 21 games in what was known as the major leagues, all during the span of a month in 1947. He had problems with racism and the poor quality of his club, the St. Louis Browns. In 2006, however, Brown’s greatness was recognized as a special committee selected him to enter the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown.

Willard Jessie Brown was born on June 26, 1915, in Shreveport, Louisiana. Some sources have cited 1911 as his year of birth, but Brown’s birth certificate, Social Security application, and census research have confirmed the 1915 date. It’s interesting to note that when he came up to the majors, some stories billed Brown as being born in 1921.1 In later decades, though, he took to saying that he was too old when he got his chance, and so dates such as 1911 and 1913 entered circulation.

Willard’s father, Manuel Brown, was born in Texas. Manuel’s wife, Allie (who died at age 100 in 1986) came from Marthaville, Louisiana.2 As of the 1920 census, the Brown family was living in Natchitoches, about 75 miles southeast of Shreveport. Manuel’s occupation was listed as mill laborer; Willard’s name was recorded as “Bud.” No other siblings are visible, though two cousins were in the house, including a girl named Cleo whom Willard viewed as a sister.3 By 1930, the family had returned to Shreveport, and Manuel had his own cabinetmaking shop. The only other member of the household listed then was Allie’s father, Louis Phillips.

Young Willard grew up around baseball. Among other things, he served as a batboy in spring training for his future team, the Kansas City Monarchs. In the 1920s, Shreveport was one of the places they liked to use to prepare for the long season.4 In 1934, Brown turned pro, since he had left school and thought baseball offered his best earning potential. He joined the Monroe Monarchs of the Negro Southern League. This club, based in another northern Louisiana city about 100 miles east of Shreveport, was owned by a wealthy local businessman named Fred Stovall. Brown signed for just $8 a week as a shortstop and pitcher, but as Louisiana sportswriter Paul Letlow observed on his blog in June 2009, the players also got room and board on Stovall’s plantation.5 “I thought that was big money,” said Brown with a chuckle in a 1983 interview.6

After one season with Monroe, Brown joined the Kansas City Monarchs, one of the premier franchises in the Negro Leagues. Owner J.L. Wilkinson spotted Buck O’Neil and Brown while Kansas City was barnstorming against the Shreveport Acme Giants in spring training.7 Wilkinson gave his recruit a $250 bonus, a salary of $125 per month, and $1 per diem meal money.8 Brown made the East-West All-Star game in 1936. It was the first of eight times for him in Black baseball’s showcase. In 1937, though, he shifted from short to the outfield, which remained his primary position for the rest of his career. He played a good deal of center field but was also a corner outfielder much of the time.

During the winter of 1937-38, Brown got his first experience of baseball in a Spanish-speaking land as he played in Cuba for Marianao. The player-manager was the great Martín Dihigo. Brown got just eight hits in 55 at-bats over the 53-game season. He did not return to Cuba after that.

The Kansas City Monarchs were highly successful in the decade from 1937 to 1946, winning six Negro American League championships. They also won the Colored World Series (as it was known at the time) in 1942. There was a tremendous amount of talent on the team, including the brilliant pitchers Satchel Paige and Hilton Smith, plus slick second baseman Newt Allen, steady first baseman Buck O’Neil, and 6-foot-6 outfielder Ted Strong. Their leading offensive weapon, though, was Brown. No less a figure than Josh Gibson called him “Home Run” Brown.

Negro League historians Larry Lester and Sammy Miller recorded the story of another of Brown’s nicknames, one that was less flattering. “Brown is what we called a Sunday player,” claimed former teammate Sammy Haynes. “Willard liked to play on Sundays when we had a full house. If the stands were full you couldn’t get him out. He could play baseball as good as he wanted to. If the stands were half empty, you might find Brown loafing that day. In fact, he didn’t play on rainy or cloudy days. That’s why we called him Sonny. He loved to play on sunny days and before big crowds. And he was a real crowd pleaser.”9

In his 1999 book about his life in the Negro Leagues, another old teammate, catcher Frazier “Slow” Robinson, echoed Haynes. “The only thing about Brown was that he never did get serious about baseball. . .he could have let the fans know he was hustling at all times.” Robinson acknowledged Brown’s power and speed, and that he was at his best in big games. Still, he rated Brown a cut below Josh Gibson in terms of consistency and all-around play. He also questioned his throwing arm, which is at odds with other descriptions.10

In this vein, many stories describe how Brown often had his nose in a copy of Reader’s Digest while stationed in the outfield. Plenty of days, he would also seemingly be in a rush to get the game over with, and would swing at anything in sight. Once he homered on a pitch that came in on a bounce. Catcher Quincy Trouppe said, “Who knows? Brown may have been as great, or greater, than Gibson, if he had been a little more patient and waited for strikes.”11 Yet there was still something endearing about Brown, as author Joe Posnanski pointed when he skillfully retold these anecdotes. Mainly, it was how good he was when he was on.12 As various people have observed, including Buck O’Neil, Brown also made things look easy.

Brown’s career with the Monarchs was interrupted in 1940, when he went to play in Mexico. Author John Virtue described how it came about. That year, “two competing six-team leagues were formed [in Mexico], creating the need for twice as many players, so the Negro Leagues were raided as never before. During the season, 63 African American ballplayers played in Mexico, four times the number that had played in 1939. They represented about 20 percent of the rosters of the Negro American League and Negro National League teams — and they were among the best players.” The new league was formed by magnate Jorge Pasquel, who six years later tried to raid the major leagues.13 The money was good: Brown got $1,000 per month. He also developed his grasp of Spanish.

Business acquaintances of Pasquel in Nuevo Laredo formed the team that Brown joined. In 294 at-bats with the Tecolotes (Owls), Brown hit .354 with eight homers and 61 RBIs. To underscore the type of hitter he was, he drew just 10 walks but struck out only 15 times. According to Virtue, Brown decided to stay in Mexico at the beginning of 1941, declining an olive branch that the Negro Leagues owners extended to jumpers.14 Other sources indicate that Brown did not play south of the border that year, and that 1941 Mexican batting statistics with his name are actually those of pitcher Barney Brown.

In the winter of 1941-42, with numerous other Negro Leaguers on the scene, Brown’s Puerto Rican career began with Humacao. He played second base and batted .409 (50 for 122) with four homers and 26 RBIs. Despite this auspicious season, though, he would not return to the island for another five years. For at least one stretch, in 1943-44, he played in the California Winter League for the Kansas City Royals, a team that featured Satchel Paige among others.15

Brown entered the U.S. Army in 1944, serving in Europe at the height of World War II. “In the Army, Brown was among those in the five thousand ships that crossed the English Channel during the Normandy invasion. A member of the Quartermaster Corps, he was not in combat but was engaged in hauling ammunition and guarding prisoners.”16 He then transferred to Special Services. In France, former Phillies pitcher Sam Nahem got him to play for the OISE All-Stars, who represented Com-Z (Communications Zone) in the 1945 ETO World Series. This integrated team boasted another Negro League star and future Hall of Famer in Leon Day. They beat the 71st Division Red Circlers, which featured several major-leaguers, including Harry Walker and Ewell “The Whip” Blackwell.17

Returning to Kansas City in 1946, Brown had what some observers believe was his best season with the Monarchs. Although the patchy data make it difficult to underpin this idea, newspaper accounts give the impression that he was the top home run hitter in the NAL that year. He added three more homers in six games during the Colored World Series (yet the Newark Eagles won after Satchel Paige and Ted Strong jumped the team with two games remaining). Brown followed up with the first of his three Puerto Rican batting titles in 1946-47, joining the club where he would play his best, the Santurce Cangrejeros (Crabbers).

In July 1947, Brown got his shot at the majors, as the St. Louis Browns signed him and infielder Hank Thompson from the Monarchs for a reported $5,000 apiece.18 The Associated Press reported, “Owner Richard Muckerman of the Browns said the two players were signed ‘to help lift the Browns out of the American League cellar.’” The Brownies also had an option on another fine Negro Leaguer, Lorenzo “Piper” Davis. The AP article added that of all the African American players signed in the year of integration, including Jackie Robinson, “Outfielder Brown was considered to be the prize package of the lot, with only his age against him.”19

Janet Bruce’s book on the Monarchs noted that Brown was unhappy. “The first time they told me I was going to the Browns — I didn’t want to go to the Browns in the first place! I said, ‘No! I wasn’t going. But [the other players] just kept on, ‘Why don’t you go on, show them what you can do.’”20

Without any time at all to acclimate in the minors, however, Brown never really got on track in St. Louis (despite displaying his enormous power in batting practice). As has often been chronicled, the atmosphere around him was charged with racism. Alabaman outfielder Paul Lehner was the unfriendliest teammate; Philadelphia A’s coach Al Simmons reportedly was one of those riding Brown hard.21

Brown’s best game in the majors was his fifth, at Yankee Stadium on July 23. He went 4-for-5 and drove in three runs as the Browns won 8-2.

On August 13, Brown hit his only homer in the majors, and the first in the American League by a Black player. It was an inside-the-parker in the eighth inning off Detroit’s Hal Newhouser; the pinch-hit blow helped the Browns rally after losing a lead in the top of the inning. The aftermath of that homer has become more memorable. Brown had used a bat belonging to outfielder Jeff Heath, but upon Brown’s return to the dugout, Heath smashed the bat against the wall rather than allow Brown to use it again.

This has often been cited as a prime example of the racial animus that Brown (and Thompson) faced in St. Louis. No doubt the perception was awful, but it is notable that in 1965, Hank Thompson mentioned Heath as one of five Browns who “went out of their way to make life easier for me and Brown.”22 In addition, Heath had given a positive report on Brown’s ability because he had faced him as Bob Feller’s All-Stars faced Satchel Paige’s barnstorming squad in the fall of 1946.23 There is also an alternate explanation for Heath’s behavior. In his biography of Heath for the SABR BioProject, C. Paul Rogers III noted that Heath was a quirky, superstitious player who “was very particular about his bats and would not allow teammates to borrow them.” Further support for the absence of a racial motive came from Browns road secretary Charlie DeWitt after that season. DeWitt said, “He said he would not have minded if Brown got a single, but he had used up one of the bat’s home runs.”24 The oddity here was that Heath — who was also widely known for his hot temper — had discarded the bat because it had lost its knob. Brown liked it because it was the heaviest he could find — he favored 40-ounce clubs.

On August 23, Browns manager Muddy Ruel released both Brown and Hank Thompson (they rejoined the Monarchs, where the money was actually better). Ruel had told Baltimore Afro-American sportswriter Sam Lacy on August 6 that “a fair trial” — which even Ruel admitted he couldn’t truly define — was still in progress.25 According to owner Muckerman, he, general manager Bill DeWitt, and Ruel had held several conferences and concluded that Brown and Thompson lacked major-league talent.26

In Brown’s 1983 account, he said that he and Thompson, although they were dissatisfied, had a choice about whether to stay or go. He said he might have stayed if the club had given him what he asked for, such as bats he could swing with. Overall, he took a dim view of the club he had left. “The Browns couldn’t beat the Monarchs no kind of way, only if we was all asleep. That’s the truth. They didn’t have nothing. I said, ‘Major league team?’ They got to be kidding.”27

St. Louis had also harbored a vain hope that the Black players might spur attendance.28 Kansas City teammate Buck O’Neil further alleged in his book, “Another real problem was that the Browns were going to have to pay the Monarchs some more money if those two guys lasted out the season, so they just released them before the season ended. Willard was bitter, you can believe that. He knew that at twenty-eight [sic] he’d never get another crack at the big leagues.”29

During the winter of 1947-48, Brown felt that he had something to prove, and had a simply monstrous Triple Crown season. It may have been at this time that sportswriter Rafael Pont Flores coined the nickname Ese Hombre. Brown hit .432, the fourth-highest single-season mark in Puerto Rican Winter League history. His 27 homers remain far and away the most in one PRWL season; the runner-up is Reggie Jackson, who hit 20 in 1970-71. Finally, his 86 RBIs rank third on the single-season list — the best total being his own 97, set two winters later. Bear in mind that the PRWL schedule was just 60 games long and the caliber of competition was high.

Author Thomas Van Hyning, who chronicled the league and the Crabbers in two books, said that pitcher Rubén Gómez called Brown “the most dominant player he had ever played with, except for Willie Mays.” Van Hyning added the view of Poto Paniagua, who took over ownership of the Santurce club in the 1970s. Paniagua “affirmed that Willard Brown was the most productive import the Puerto Rico Winter League ever had. [He] told me that Brown would have been a big league superstar had he (Brown) been given a chance at a much younger age.”30

Brown returned to the Monarchs in 1948, pulling down a monthly salary of $600.31 About the following summer in Kansas City, Buck O’Neil later said, “The best club I ever managed was the 1949 team.” The team photo showed little Willard Jr. — the only child Ese Hombre had with his wife, Dorothy — posing in front of his father.32 Unfortunately, further details about this woman are presently unavailable. As Willard Jr.’s wife Mary recalled in 2010, Dorothy was some years older than Willard Sr. The marriage broke up when the boy was about nine years old.

The winter of 1949-50 saw Brown win his second Triple Crown in Puerto Rico, earning $200 in bonus money ($100 for the batting title and $50 apiece for the other two legs). He edged his teammate Bob Thurman, another powerful Negro Leaguer, for the batting title, .354 to .353. Brown and Thurman (known as El Múcaro, or The Owl, in Puerto Rico) formed “the most feared tandem in league history.”33

In February 1950, Brown batted .348 in the second Caribbean Series as a reinforcement for the PRWL champs, the Caguas Criollos. An article from early April showed that Brown had not reported to the Monarchs’ training camp in San Antonio, Texas. Instead, he was said to have signed to play in Venezuela.34 He joined the club Orange Victoria, a newly assembled squad taking part in the fifth season of pro baseball in Maracaibo in the state of Zulia. It included other prominent Negro Leaguers such as Ray Brown, Howard Easterling, and Wilmer Fields.35

After a couple of months or so, Willard Brown then returned to Kansas City.36 The Monarchs also featured 21-year-old Elston Howard.37 That July, Yankees scout Tom Greenwade came to check out Brown. Instead, Buck O’Neil said, “Willard’s a fine player. . .but Elston Howard is the player you’re looking for.”38 Brown’s reaction is not known and there are no available records of any action with the Monarchs that summer.

The following month, the Ottawa Nationals of the Border League (Class C) persuaded Brown to join them, although reportedly he was reluctant to travel that far north.39 The Montreal Gazette praised his play, saying, “Willard Brown. . .whom the Nationals secured from the Kansas City Monarchs last month, proved a big factor in Ottawa’s drive to the pennant. He hit at a .400 clip and saved several games through sensational fielding.”40 Including playoff action (the Nats lost the final in six games), Brown wound up hitting .352 in 128 at-bats across 30 games.

In February 1951, Santurce won the PRWL title and then went on to take the third annual Caribbean Series in Venezuela. Right around that time, a newspaper in Guadalajara, Mexico, El Informador, had a big headline announcing that Brown had accepted a contract with the local team, the Jalisco Charros. The manager was Quincy Trouppe.41 As late as April, a photo with fellow Negro Leaguers Max Manning, Bill Greason, and Trouppe indicated that Willard would be a Charro.42 Instead, after 11 years away, he returned briefly to Nuevo Laredo that month.43 He soon came back to Kansas City, however, winning the Negro American League batting title in 1951 with a .417 average, though by that point the level of play had dropped off sharply.

Ese Hombre also spent some time in the Dominican Republic in the summers of 1951 and 1952. Pro baseball had resumed there in 1951, but the league would not switch to the winter until 1955. With the Escogido Leones, Brown hit .253 with 17 RBIs in 1951, lifting those numbers to .301 and 28 the following year. One source says that Willard played for Cervecería Caracas in Venezuela in the winter of 1951-52.44 This does not appear to be the case, though, because The Sporting News showed him in Santurce at the beginning and end of the season, noting that he had been sidelined for a month with an ailing knee.45

The Crabbers won the PRWL title again in 1952-53 and thus went on to another Caribbean Series. They won their second double winter championship, going 6-0 thanks to MVP Brown’s four home runs and 13 RBIs. In three Caribbean Series overall, he hit .343 with five homers and 19 RBIs.46

Brown returned to the U.S. for the summers of 1953 through 1956, playing for various teams in the Texas League, plus a little bit in the Western League. Although the Texas League was only Double-A ball, he was still a potent hitter. His best output during this period came in 1954, when he had 35 homers and 120 RBIs while batting .314. In both 1953 (Dallas) and 1954 (Houston, where he played 36 games after 108 with Dallas), Brown’s clubs won the league championship.

Turning back to winter ball in Santurce, Brown’s last full season there was 1953-54, but he made a brief return in 1956-57, going 6 for 23. Ese Hombre finished his Puerto Rican career with a .350 batting average, the best in league history. His 101 home runs rank fourth all time behind Bob Thurman, José Cruz, and Elrod Hendricks; his 473 RBIs rank seventh. When the Puerto Rican Baseball Hall of Fame inducted its first class in October 1991, Brown was among the elite group of 10 players.

In the twilight of his career, Brown played in 1957 with the Minot Mallards of the Manitoba-Dakota (ManDak) League, which featured many old Negro Leaguers: He hit .307 with nine homers and 29 RBIs in 150 at-bats. Brown’s plaque in Cooperstown indicates that he played in the Negro Leagues in 1958. Indeed, an article in the Schenectady Gazette from July 1958 billed him as “the star of the Monarchs” once more as the “Kansas City” club (by then based in Grand Rapids, Michigan) visited Hawkins Stadium in Albany, New York.47 By this stage, though, the Negro American League was a lower-echelon barnstorming attraction.

After he finally retired from baseball, Brown made his home in Houston. Little information is available about his last three-plus decades. Although James Riley’s Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues notes briefly that Brown worked in the steel industry, there is not much more to go on. Interviews with and about him during this period focused on the past rather than the present.

In mid-December 1979, Brown returned to Puerto Rico for an Old-Timer’s Day. He told local baseball man Luis Rodríguez Mayoral that the island “was where I was treated best.”48 Said Pedrín Zorrilla, who owned the Santurce Crabbers in Brown’s greatest days, “it was the man. . .the artist. . .it was those things [about him] that they cheered. He didn’t have to be Puerto Rican. The Puerto Ricans love baseball, and Willie Brown could play it, and by that very fact he became a brother to us.”49 Thomas Van Hyning offered still more detail about the deep affection that Brown and the boricua people shared.50

Willard Brown passed away on August 4, 1996, in Houston. He was 81, had been suffering from Alzheimer’s disease since 1989, and had entered a Veteran’s Administration hospital in the early ’90s. A sketch about Brown in Volume 36 of Contemporary Black Biography said that he had previously slipped into poverty. His son Willard Jr. had died two years previously.

In his New Historical Baseball Abstract (2001), analyst Bill James likened Brown to one Hall of Famer, one who would go in later, and two other very potent sluggers. He said, “Maybe comparable to José Canseco, Juan González, André Dawson or Frank Robinson.”51 In February 2006, a voting committee of 12 historians specializing in Negro League and pre-Negro League baseball convened under former Commissioner Fay Vincent. They elected 17 candidates to Cooperstown, including 12 players and five executives. Among them was Willard Brown.

In 2007, Louisiana sportswriter Ted Lewis offered two quotes that summed up the choice well. “‘I don’t think he would have been surprised by being elected,’ said Mary Brown, who represented her late father-in-law in Cooperstown last summer.” Lewis also spoke to Dick Clark, co-chairman of SABR’s Negro Leagues Committee and a member of the Hall of Fame selection committee. “Brown’s credentials made his election an easy one. . . ‘Willard Brown was the preeminent right-handed slugger for the Negro American League throughout the ’40s,’ Clark said.”52

Acknowledgments

Continued thanks to Eric Costello for his additional research. Thanks also to Mrs. Mary Brown and SABR member Dwayne Isgrig. A question from SABR member Alan Cohen about Brown’s action in 1950 prompted an update to this biography in January 2024.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted:

1920 and 1930 census records, courtesy of www.ancestry.com

Interview with Willard Brown for the University of Kentucky Libraries A.B. Chandler Oral History Project. Conducted by William J. Marshall in South Point, Ohio, on June 22, 1983.

Negro Leagues Baseball e-Museum profile of Willard Brown (http://coe.ksu.edu/nlbemuseum/history/players/brownw.html)

Crescioni Benítez, José A. El Béisbol Profesional Boricua. San Juan, Puerto Rico: Aurora Comunicación Integral, Inc. (1997).

Bjarkman, Peter C. Diamonds Around the Globe: The Encyclopedia of International Baseball. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press (2005).

Treto Cisneros, Pedro, editor, Enciclopedia del Béisbol Mexicano. Revistas Deportivas, S.A. de C.V. (1998).

Figueredo, Jorge. Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 1878-1961. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co. (2003).

Cruz, Héctor J. El Béisbol Dominicano. Accessible online at http://www.scribd.com/doc/25085233/EL-BEISBOL-DOMINICANO-2

Sketch on Willard Brown with compilation of statistics from across his career, Western Canada Baseball website (http://www.attheplate.com/wcbl/majorleaguers.html)

Willard Brown discussion on Baseball Think Factory website (http://www.baseballthinkfactory.org/files/hall_of_merit/discussion/willard_brown)

Swanton, Barry. The ManDak League. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co. (2006).

Henderson, Ashyia, editor. Contemporary Black Biography, Volume 36. Farmington Hills, Michigan: Gale Group (2002).

Notes

1 Frederick G. Lieb, “Gates Rusting, Browns Rush in 2 Negro Players,” The Sporting News, July 23, 1947: 8.

2 Allie Brown obituary, Orlando Sentinel, July 14, 1986.

3 Interview with Willard Brown for the University of Kentucky Libraries A.B. Chandler Oral History Project. The interview (hereafter Marshall-Brown interview) was conducted by William J. Marshall in South Point, Ohio, on June 22, 1983.Allie Brown’s obituary also refers to Cleo as a daughter.

4 Janet Bruce, The Kansas City Monarchs: Champions of Black Baseball, Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas (1985):, 27.

5 James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues, New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers (1994). Paul Letlow, “The Monroe Monarchs.” Paul Letlow’s Louisiana Sports Shorts (http://louisianasportsshorts.blogspot.com/2009/06/monroe-monarchs.html), June 29, 2009.

6 Marshall-Brown interview.

7 Bruce: 26.

8 Riley.

9 Larry Lester and Sammy Miller, Black Baseball in Kansas City, Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing (2000):, 65.

10 Frazier Robinson with Paul Bauer, Catching Dreams, Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press (1999): 54-55.

11 Bill James, The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract, New York: Simon & Schuster (2001): 191.

12 Joe Posnanski, The Soul of Baseball, New York: HarperCollins Publishers (2007): 107-108.

13 John Virtue, South of the Color Barrier, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co. (2008): 74, 76.

14 Virtue: 94.

15 William McNeil, The California Winter League, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., (2002): 213-214.

16 Riley.

17 Profile of Willard Brown, Baseball in Wartime, (http://www.baseballinwartime.com/player_biographies/brown_willard.htm)

18 Lieb.

19 “Browns Sign Two Negroes; Buy Option on Another,” Associated Press, July 18, 1947.

20 Bruce: 115.

21 “Lehner Kills AWOL Rumor, Was Only Visiting Doctor,” The Sporting News, July 30, 1947: 11. Rick Swaine, The Integration of Major League Baseball, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co. (2009):, 122.

22 Hank Thompson with Arnold Hano, “How I Wrecked My Life — How I Hope to Save It,” Sport, December 1965.

23 “Prospectus Q&A: Chris Wertz.” Baseball Prospectus, (http://www.baseballprospectus.com/article.php?articleid=11462), July 14, 2010. “Feller’s All-Stars Attract 148,200 in 15 Exhibitions,” The Sporting News, October 16, 1946: 23.

24 Gordon Cobbledick, “Premature Shower in Final Game of ’47 Proved Washout for Heath as a Brownie,” The Sporting News, December 17, 1947: 7.

25 Sam Lacy, “Looking ’em Over,” Baltimore Afro-American, August 6, 1947. Reprinted in Black Writers/Black Baseball, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company (2007): 22.

26 Ray Nelson, “More Negroes May Be Signed in Future,” Says Muckerman,” St. Louis Star & Times, August 25, 1947: 17.

27 Originally published in the Kansas City Star, unknown date, 1985.

28 Lieb.

29 Buck O’Neil with Steve Wulf and David Conrads, I Was Right on Time, New York: Simon & Schuster (1996): 183.

30 Thomas Van Hyning, The Santurce Crabbers, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company (1999): 28.

31 Neil Lanctot, Negro League Baseball: The Rise and Ruin of a Black Institution, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press (2004): 463.

32 Lester and Miller: 52.

33 Van Hyning: 25, 32, 144. The “Owl” nickname referred to Thurman’s pitching performance in night games in 1947-48.

34 “Monarchs Start Drills at San Antonio; Willard Brown, Lefty LaMarque Absent,” Kansas City Call, April 7, 1950: 8.

35 Javier González and Carlos Figueroa Ruiz, El Vuelo de Las Águilas, Caracas, Venezuela: Banesco Banco Universal (2021): 101.

36 “Willard Brown Wins Friends in Ottawa,” ,” Kansas City Call, September 29, 1950: 8.

37 “Kaysee Monarchs to Launch Training Drills on April 1,” Washington Afro-American, March 21, 1950: 19.

38 Arlene Howard with Ralph Wimbish, Elston and Me, Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press (2001): 22.

39 “Nats Using New Pitcher; Brown Due?” Ottawa Citizen, August 11, 1950: 14.

40 “Ottawa Nationals Win Border Title.” Montreal Gazette, September 9, 1950: 8.

41 “Willard ‘Home Run’ Brown Ha Sido Contratado por Jalisco,” El Informador (Guadalajara, Mexico), February 21, 1951: 1.

42 El Informador, April 11, 1951: 1.

43 El Informador, April 20, 1951: 6. Jorge Alarcón, “Crespo Wins 4 Straight in Mexican Loop,” The Sporting News, April 25, 1951: 32.

44 William F. McNeil, Black Baseball Out of Season, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co. (2007): 179. Note also that Brown is not listed in Venezuelan statistics.

45 Santiago Llorens, “Brown Goes on Hit Streak for Santurce,” The Sporting News, February 20, 1952: 27.

46 Thomas Van Hyning, Puerto Rico’s Winter League, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co. (1995): 142.

47 “Negro Teams in Hawkins Over Weekend,” Schenectady Gazette, July 5, 1958.

48 Van Hyning, The Santurce Crabbers: 134.

49 Samuel Regalado, Viva Baseball!, Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press (1998): 70.

50 Van Hyning, Puerto Rico’s Winter League: 142.

51 James.

52 Ted Lewis, “Willard Brown’s Legacy Remains As Prominent Slugger.” Original publication may have been in the New Orleans Times-Picayune, where Lewis was employed as sportswriter. Reposted on the W.E. A.L.L. B.E. blog, June 15, 2007. (http://weallbe.blogspot.com/2007/06/legend-of-willard-brown-forgotten.html)

Full Name

Willard Jessie Brown

Born

June 26, 1915 at Shreveport, LA (USA)

Died

August 4, 1996 at Houston, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.