Ruppert Stadium (Kansas City)

This article was written by Bill Lamberty

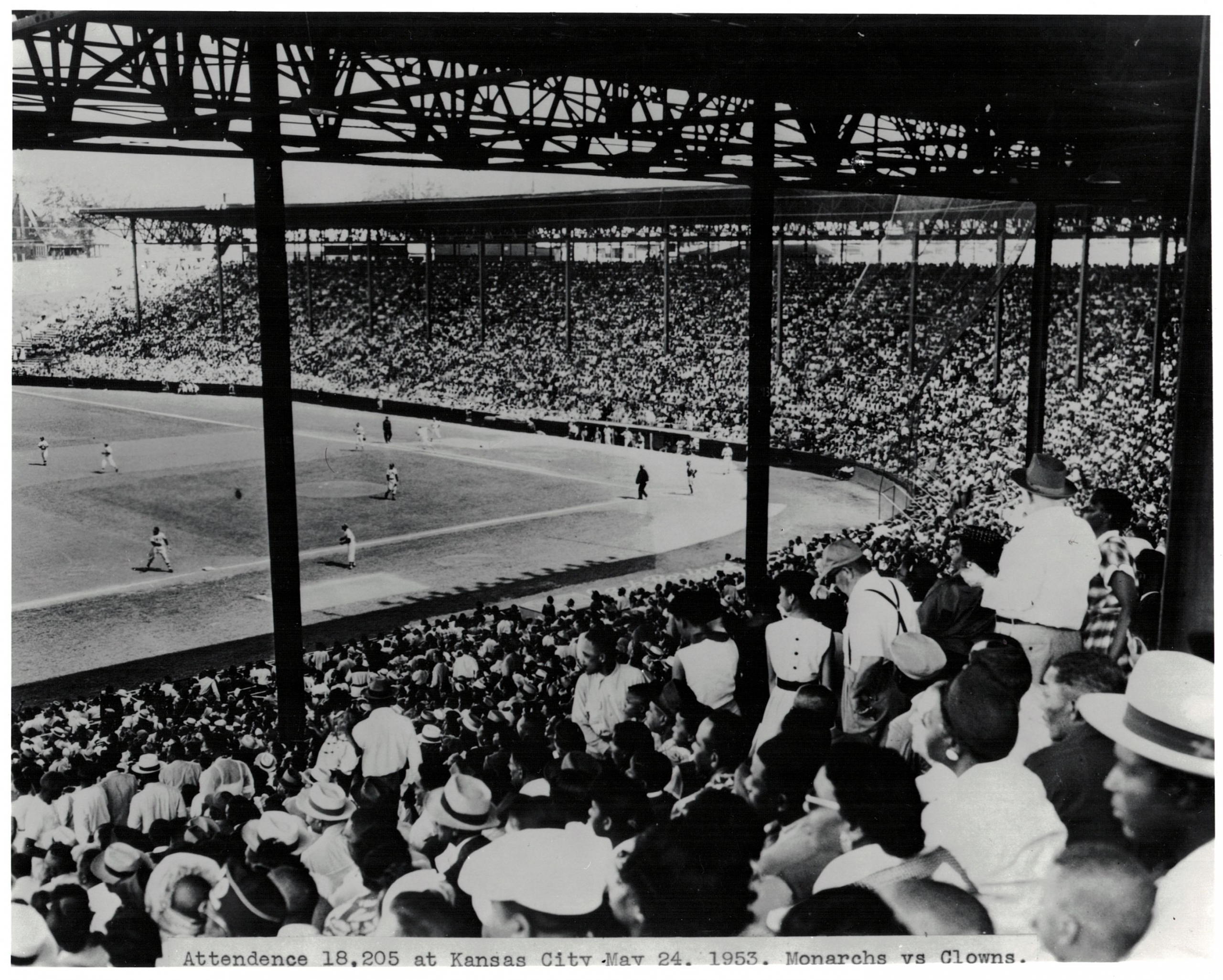

Ruppert Stadium was the home of the Kansas City Monarchs beginning in 1923. The stadium was first known as Muehlebach Field (1923), then Ruppert Stadium (1937), and later Blues Stadium (1943). It was completely rebuilt and renamed Municipal Stadium in 1955. (Courtesy Noir-Tech Research, Inc.)

Satchel Paige left the mound in Kansas City’s Municipal Stadium to enormous ovations many times in his pitching career, barely noticing the fuss of adoring crowds and some of baseball’s brightest stars. However, September 25, 1965, was different.1

Long removed from his prime as a Negro Leagues legend, or even as the White major leagues’ oldest player when he debuted for the Cleveland Indians in 1948, the man estimated to have pitched to more batters in more ballparks than anyone else in history left his final big-league game as a 59-year-old (his most-accepted age) future Hall of Famer on a night that began as a stunt but ended adding to his amazing legend. He used 28 pitches to twirl three scoreless innings for the hometown Kansas City A’s against Boston, with Carl Yastrzemski’s first-inning double the only hit allowed.2

Signed by Athletics owner Charlie Finley for the “princely sum of $3,500”3 to pitch one last time, Paige famously occupied a wooden rocking chair in the bullpen before the game and in the dugout between innings. A hired nurse rubbed liniment on his pitching arm, and a personal waterboy brought him beverages. Negro Leagues legends Buck O’Neil, Cool Papa Bell, Hilton Smith, and Bullet Rogan returned to their former stamping grounds for a luncheon and brief exhibition game before Kansas City’s game against the Red Sox. Future major leaguers Rick Sutcliffe and Frank White joined the nearly 10,000 fans in attendance, a remarkable jump from the 690 fans who had watched the A’s two days earlier.4

Paige’s career intersected with Kansas City’s longest-lasting ballpark (until the Royals begin their 1973 season at Royals Stadium, which was renamed Kauffman Stadium in 1993) for much of its lifespan, and that stadium also links the community’s rise “from rowdy frontier backwater to major league city.”5

The Municipal Stadium in which Paige pitched in 1965 was a ballpark known by several names over the course of its lifetime. (See the Editor’s Note at the end of this article for a chronology of stadium names.)

Its construction in 1923 as Muehlebach Field provided a permanent home for the minor-league Blues and the Negro National League Monarchs, by then three years into their existence as a charter member of that loop, and Paige likely pitched there beginning in the late 1920s with the Birmingham Black Barons.6 Before its construction on what was once a swimming hole, frog pond, and ash heap, the city’s various ballclubs played in Athletic Park (the 1884 home of Kansas City’s Union Association team), Association Park (1886-88, home of the Kansas City Cowboys of the National League and American Association), Exposition Park (1888-89, home of the Double-A Cowboys), and Gordon and Koppel Field (1914-15, Federal League Packers).7

The ballpark built by brewer and hotelier George Muehlebach for his Blues opened on July 3, 1923, with home plate resting near the intersection of 22nd Street and Brooklyn Avenue. From 1920 to 1922 the Blues and Monarchs had played in Association Park, a single-deck wooden structure owned by George Tebeau, not far from the city’s 18th and Vine District. When he and Muehlebach fell into a dispute in 1922, members of the local Black press “hoped that if a fight between the two were to force Muehlebach to build a new stadium, the Monarchs could continue their lease with Tebeau for the park at Nineteenth and Olive and thus have a park of their own.”8 Monarchs owner J.L. Wilkinson could not afford Tebeau’s lease terms and, not long after, “a railroad exercised an option to run tracks through the property” to end its time as a ballpark.9

In its original incarnation, Muehlebach’s dimensions favored pitching. From home plate to center field was a 450-foot stretch; the foul poles each stood 350 feet distant.10 The ballpark rested a mile and a half southeast of downtown in a primarily Black neighborhood, across the street from a high school and within walking distance of legendary barbecue restaurants like Arthur Bryant’s and Gates BBQ.

The intersection of 18th and Vine Streets, just three-quarters of a mile from the ballpark and only one block from the Paseo YMCA, which hosted the meeting that formed the Negro National League in 1920, formed the heart of Kansas City’s Black community for much of the twentieth century. “The epicenter of the African American community was located around 18th Street between Vine and The Paseo,” historian Japheth Knopp wrote in the Spring 2016 Baseball Research Journal. “Businesses of all types, from barber and shoe repair shops to doctors’ and lawyers’ offices were found in this neighborhood. This section of town was perhaps known best for its night life, with patrons packing clubs with colorful names such as the Cherry Blossom, the Chez Paree, Lucille’s Paradise, and the Ol’ Kentuck’ Bar-B-Q.”11

Monarchs players, as well as Negro League opponents, patronized the nearby Street Hotel, called by longtime Monarchs player and manager Buck O’Neil “the best black hotel in Kansas City at the time.”12 Post-World War II economic expansion kept the boundaries of Kansas City’s Black neighborhood fluid, but through much of the ballpark’s existence, the boundaries formed by “Ninth street south to Twenty-eighth and from Troost east to Indiana Street” allowed “Kansas City’s Blacks to create) a network of businesses, social organizations, fraternal groups, and churches.” Yet, the city’s rigid segregation forced substandard living conditions upon an area that resonated with pride. “The wards in which blacks lived had the highest percentage of rental housing and the lowest of resident-owned housing in the city. The illiteracy rate was ten times higher; the death rate was twice as high as for white Kansas Citians.”13

Still, the area encompassing the ballpark and the 18th and Vine District pulsated with joy. Milton Morris, a neighborhood saloonkeeper, told author and historian Janet Bruce, “Kansas City was swinging. Nobody slept — they were afraid they’d miss something.” Musicians considered the 18th and Vine district as a venue for a continual “jam session.”14

Particularly in relation to the Monarchs, baseball was deeply rooted in the neighborhood. Longtime Monarchs second baseman Newt Allen helped with the large canvas tarp that covered the infield during rainy times and as an “ice boy at the American Association Park when the Monarchs organized in 1920. He practiced with the team, pulled the canvas (tarp) over the field, and in return received two or three baseballs from the groundskeeper.”15 Frank Duncan toiled as a batboy for the view that work afforded, and “Chet Brewer remembered having sat up in a tree outside the left-field grandstand at Muehlebach Stadium watching Bullet Joe Rogan pitch” as a youngster, dreaming of the day he might toe that same rubber.16

The players who did not take in-season residence at the Street Hotel often lived in the neighborhood near the ballpark. “We were kind of special in the neighborhood,” O’Neil recalled, “And as far as I recall we were a bit more special than” Kansas City Royals players in later years, when that team moved to distant Royals Stadium, “because of the fact that it was all black and we mingled with all black (people).”17

During the time when the Blues and Monarchs shared the ballpark, it provided as many stars as the jazz district, among them Al Rosen, Mickey Mantle, and Phil Rizzuto, along with Blues manager and Kansas City native Casey Stengel. Among the Negro Leagues greats who called the ballpark home were Paige, Ernie Banks, Jackie Robinson, Bullet Rogan, Hilton Smith, and Turkey Stearnes. All earned induction into the National Baseball Hall of Fame; other notables included Buck O’Neil, John Donaldson, and Elston Howard. Jazz stars made regular stops in Kansas City, including Count Basie, Dizzy Gillespie, and Louis Armstrong.

While both the American Association Blues and the NAL Monarchs called the ballpark home until the Athletics arrived in 1955, the organizations had vastly different relationships with it. The Blues played a standard American Association schedule and commonly drew an average of around 2,000 fans to the 80 or so home games per season. The Blues played in four Junior or Little World Series from 1923 to 1954, their lifetime playing home games at 22nd and Brooklyn. The Blues beat Baltimore five games to four in 1923 and beat Rochester by the same tally in 1929. The team lost to Rochester (4-3 in 1952) and Montreal (4-1 in 1953) in best-of-seven series near the end of Kansas City’s time as a minor-league city.18

The Monarchs, on the other hand, often found the road a more profitable venture, writes author and Negro Leagues historian Phil S. Dixon. “Starting in 1931, the Monarchs had become a barnstorming team. They were continuously on the road, a vast difference compared to their pennant run in 1923, when they played a record 57 games in Kansas City. In 1934, the number of Monarchs home games dipped to three — and one of these games was played across the Missouri River in Kansas City, Kansas.”19

While barnstorming took the Monarchs on the road, crisscrossing the near South and Midwest, it also gave the team opportunities to host other clubs on similar tours. The season before the ballpark opened, any possibility of the Blues and Monarchs deciding city superiority ended with the Negro Leagues entry avenging a city series loss of one year earlier with a five-games-to-one best-of-nine series win against the Blues. Muehlebach swore his team would never again play the Monarchs, a vow he kept, and Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis clamped down on major-league players barnstorming against Negro League teams in the offseason. The Monarchs’ doubleheader wins over a club featuring Yankees stars Babe Ruth and Bob Meusel in Association Park (October 6, 1922) figured into that decision.20 Ruth never bowed to race-relations norms of the time, and Kansas City offered a stage. In addition to his appearance against the Monarchs in 1922, Ruth barnstormed against teams featuring Negro Leagues players throughout his career. In 1927 he appeared in a Kansas City fundraising event at the Guardian Angels Home for Negro Children and four years later was in town to play a night game against the Monarchs, which was rained out and not rescheduled.21

In 1934, with America struggling through the Great Depression and the St. Louis Cardinals holding the imagination of Middle America captive with the antics of the Gas House Gang teams, Redbirds pitchers Dizzy Dean, his brother Paul, and other major-league stars commenced a tour that featured the Monarchs and three Negro Leagues teams — the New York Black Yankees, Philadelphia Stars, and Pittsburgh Crawfords — which has been chronicled brilliantly by Dixon in The Dizzy and Daffy Dean Barnstorming Tour — Race, Media, and America’s National Pastime.

Muehlebach Field and the Monarchs hosted the Dean All-Stars on October 6, 1934, with 14,000 fans on hand. T.J. Young tripled off Paul Dean in the second inning, scoring the only run the Monarchs needed in a 7-0 win. Andy Cooper anchored a brilliant pitching performance for a Kansas City team that scored off both Dean brothers and future big leaguer Mort Cooper. Young expressed gratitude for the opportunity to perform against the game’s best-known pitchers — “All my life it’s been one of my ambitions to hit the best hurlers in the majors” — and Dizzy Dean praised the Monarchs hitters.22

In 1930 the Monarchs and Muehlebach Field played a role in altering baseball history by hosting night baseball games. Monarchs owner J.L. Wilkinson, in an effort to fight fiscal losses brought on in part by the Great Depression, conjured up the idea of a portable lighting system that could be used at home and could also be taken on the team’s tours. The Giant Manufacturing Company of Omaha, Nebraska, built a system of telescoping poles supporting six four-foot-wide floodlights that rose 45 to 50 feet above the playing surface. The poles attached to truck beds, with the vehicles stationed down each foul line and at advantageous points around the field. The system cost between $50,000 and $100,000, and while the crashing economy forced ticket prices from 65 cents per ticket down to a low of 25 cents, Wilkinson credited the lighting system with keeping his ballclub afloat during the difficult times.23

The environment in the ballpark mirrored the good-time culture of the neighborhood, and its role as a cultural cauldron. Bruce wrote, “The crowds at Negro-league baseball were loud and lively in support of the home team. The ball-park behavior of many of the newly arrived southerners, however, sometimes offended the sensibilities of middle-class blacks. They saw this boisterous ‘rowdyism’ (including everything from drinking and gambling to harassing the umpires, throwing seat cushions, and fighting) as an embarrassment for the race.”24 Still, Dixon called Kansas City a “really jumping” and “robust Midwestern city” in the late 1930s, “the prairies’ capital for ethnic sports, entertainment, music and religious activities. Sunday was the big day for baseball, the day when African-American fans came out to support their Monarch team at Ruppert Stadium, and most came directly from church.”25 That tradition resonates to this day, with the Royals hosting an annual “Dressed to the Nines Day” and encouraging fans to arrive for a selected Sunday game honoring the Negro Leagues dressed in a manner befitting the glory days of Ruppert Stadium.

Buck O’Neil praised Ruppert Stadium in Phil S. Dixon’s John “Buck” O’Neil — The Rookie, The Man, The Legacy, calling it “an outstanding park, always had good groundskeepers, the grounds were always good, and you’re playing at home. And when you say ‘playing at home,’ in Kansas City it meant quite a bit to you cause you always had a lot of people there, and these same people, after you got through playing ball you were going to meet them at the Blue Room or (at) the Subway (club), it was just a great feeling. All of the ballplayers that played all over the country wanted to come to Kansas City. [They] liked the park and they liked the city.”26 O’Neil added that in most Negro Leagues ballparks the visiting team dressed either before arriving at the ballpark or in the same space the home team used, while Ruppert Stadium offered a full visiting clubhouse.27

The ballpark also offered a glimpse into the city’s strong but ever-shifting segregation, with ownership regimes setting their own standards. While George Tebeau forced all Black fans into segregated seating sections for all games, even when Negro League teams played, Muehlebach relaxed those standards when he built the ballpark at 22nd and Brooklyn. Seating was segregated for Blues games, but those signs were removed when the Monarchs played. When former Cubs star Johnny Kling purchased the Blues and the ballpark in the mid-1930s, he desegregated it for all games, but under Ruppert’s management fans at Blues games again became separate by race.28 As was the case in Kansas City, college and professional sports across the nation stood as local negotiation grounds for race relations during the first three-quarters of the twentieth century.

In the years after World War II, baseball again took center stage in the sporting consciousness, and cities across the nation began dreaming of attaining major-league status. Kansas City was among the communities hoping to become a “major-league city,” but no American or National League franchise had moved since 1903. In 1953, though, the Boston Braves moved to Milwaukee. One year later the St. Louis Browns relocated to Baltimore. Suddenly franchise relocation became reality, and the Athletics emerged as a target due to the Mack family’s struggle to keep the team financially viable in the two-team Philadelphia market.29

By 1953, Chicago businessman Arnold Johnson owned both Yankee Stadium and Ruppert Stadium in an arrangement that benefited both the New York American League club and Johnson financially. That served as Johnson’s entry into the process of pursuing a major-league franchise, and through the summer and fall of 1954 in a series of meetings, negotiations with A’s owner Connie Mack and his family, and occasional interventions by baseball power brokers, he pursued Philadelphia’s American League entry in a very public way. Finally, on November 12, Johnson beat a group of local investors to Mack’s Germantown apartment and acquired the elder statesman’s stock in the A’s to gain controlling interest. That helped pave the road to relocation to Kansas City.30

One of the elements that made Kansas City an attractive location was the idea that Ruppert Stadium could be rebuilt quickly into a major-league ballpark because the subterranean footings had been designed three decades earlier with that in mind. However, exposing the structure’s underpinnings showed that that was not the case, and a rebuild could have been considered unsafe for what was there. The site was excavated in December 1954, and, in the first month of 1955, city officials formed a plan with representatives of the Webb-Winn-Senter corporation that had consolidated to build a big-league ballpark in three months to “make a civic occasion out of the first pouring of the concrete for the new footings.”31

Construction progressed rapidly and echoed a past project. In 1900 Kansas City had been forced to rebuild its convention center in three months to host the Democratic National Convention, and 55 years later a similar race against the clock began. All parties made public mention that, in such a public-private partnership, “rarely had there been such harmony displayed.”32 With cars regularly slowing on Brooklyn Avenue so occupants could gaze at the construction, up to 400 men worked long hours to complete the task. Creation of the Kansas City Stadium Association allowed city and business leaders to circumvent “rules made to protect city voters.” As construction progressed into February, even Yankees manager Casey Stengel expressed admiration.33

Legal and financial maneuvering continued almost until the day the players arrived from spring training. More than 100,000 fans welcomed the squad with a parade, and on April 12, 1955, the team opened Kansas City’s era as a major-league community with a 6-2 win over the Detroit Tigers. The 32,147 fans gathered at Municipal Stadium comprised the city’s largest crowd ever for a sporting event.34

During the Athletics’ stay as the ballpark’s home team, the franchise enjoyed little on-field success. The Athletics’ sixth-place finish in 1955, its first season in Kansas City, was its highest ever there. After the team drew more than 1 million fans in each of its first two seasons, attendance steadily declined before spiking in 1966 and 1967, when owner Charles O. Finley began advocating for another move (which came in 1968, to Oakland). Despite the abysmal on-field performance, the A’s era brought considerable whimsy to the ballpark. The phenomena of the era included a zoo in the embankment beyond right field featuring “Charlie O. the Mule, sheep, China golden pheasants, Capuchin monkeys, German checker rabbits, peafowl, and a German shorthaired pointer dog named Old Drum,” with the animals fed by “fresh food from the K.C. Farmers Market.”35 Detroit players were alleged to have got the monkeys drunk with vodka-soaked oranges one night, and for a time a mechanical rabbit named Harvey sprang from the earth near home plate to provide the umpire with clean baseballs. After Finley became convinced that one of the Yankees’ keys to success was Yankee Stadium’s short right-field porch, the A’s owner created a 296-foot porch in right field before the 1965 season. After Commissioner Ford Frick ordered the wall moved back, Finley created a flimsy half-pennant porch that jutted in before returning to regulation distance. The home-plate umpire ordered that removed before the game began on Opening Day 1965, thus ending that episode.36

The Athletics moved to Oakland after the 1967 season, and Major League Baseball granted Kansas City an expansion franchise to begin play in 1969. Contrasting Finley’s flamboyance (and the Arnold Johnson era, when promising young players were regularly shuttled to the Yankees), local businessman and entrepreneur Ewing Kauffman ran the Royals with relative dignity and professionalism. The Royals joined the Chiefs, formerly the AFL Dallas Texans, who moved to Kansas City in 1963 and eventually joined the NFL when the leagues merged, as the ballpark’s last act. The Chiefs of the 1960s brought thrills and glory to Municipal Stadium, winning the 1966 AFL championship and the Super Bowl after the 1969 season and serving as the home team for nine future Pro Football Hall of Fame players or coaches. It also precipitated the ballpark’s demise, when the NFL passed minimum capacity requirements of 50,000 beginning with the 1971 season that Municipal Stadium could not meet.

Municipal Stadium served as home ground for many brilliant major-league baseball players, although the best seasons of most stars occurred elsewhere. Vic Power moved from Philadelphia to Kansas City with the team, but his best years came in Cleveland. Bob Cerv and Roger Maris had good years with the A’s but starred on World Series winners with the Yankees, while future stars like Sal Bando, Bert Campaneris, and Reggie Jackson cut their teeth in Municipal Stadium before starring for Oakland’s dynasty teams of the early 1970s. Several of the Royals’ all-time greatest players also roamed Municipal Stadium — John Mayberry, Freddie Patek, Amos Otis, Cookie Rojas, and Paul Splittorff — but rose to stardom in the later Royals Stadium. One of the finest Royals to call 22nd and Brooklyn home, 1969 American League Rookie of the Year Lou Piniella, starred for the Yankees in the late 1970s but found true stardom as a World Series-winning manager with the Cincinnati Reds in 1990. In that way, he joined the list of future managerial stars to call Municipal Stadium their home as players that includes Hank Bauer, Doc Edwards, Whitey Herzog, Dick Howser, Rene Lachemann, Tony LaRussa, Tommy Lasorda, and Billy Martin.

Ruppert Stadium provided the setting for baseball legend Lou Gehrig’s final stanza. After 10 Yankees games in 1939 Gehrig famously pulled himself from the lineup before a game at Detroit. He never played in a major-league game again, but as a team captain continued to travel with the team. A 13-game road trip in early June took the team to the American League’s western-most cities, Chicago and St. Louis, and after sweeping a doubleheader against the Browns on June 11 New York traveled to Kansas City for an exhibition against its top minor league team.37 Two days before the exhibition Gehrig disclosed his late-June appointment at the Mayo Clinic to attempt to diagnose his “sluggishness,” so his status as an active player remained in limbo when the Yankees arrived in Kansas City. On the day that the Baseball Hall of Fame officially opened in Cooperstown, New York, 23,864 fans crowded into Ruppert Stadium, more than 6,000 more than its listed capacity, filling every corner of the property and even sitting on the stadium’s roof. As a tribute to the fans, Gehrig opted to play in that contest, grounding out in his only plate appearance and handling four chances at first base in his three innings. It marked his final appearance on a baseball diamond.38

As Satchel Paige’s career ended in Ruppert Stadium’s twilight, in many ways it began there, too. By his estimation he pitched in 2,500 ballparks during his career, but Paige experienced his strongest feelings for a home ballpark when he joined the Monarchs in 1941. Paige found a kindred spirit in Wilkinson, “an unlikely mentor to the Negro League icon” who “did whatever it took for his players and teams, choreographing games, recruiting promising rookies, providing grubstakes along with counsel, and maneuvering around Jim Crow wherever the Monarchs went.”39 Similarly, Paige fell in love with Kansas City, buying his first home and enjoying the cultural opportunities of a thriving African American community that “orchestrated the jazz, belted out the blues, seared the barbecue, and supplied much of the sweat that fed the economic boom.”40

Kansas City’s Ruppert Stadium began as a minor-league ballpark that also hosted a legendary Negro Leagues squad, underwent a rebuild, then served as home for a big-league team in 13 of its final 15 seasons. In this way, it fits into a category of ballparks that allowed major-league baseball to expand relatively quickly, usually to the west, with communities generally making rapid upgrades to smaller existing facilities. Beginning with the St. Louis Browns’ move to Baltimore in 1954 — which transitioned a 52-year old multi-use facility into Memorial Stadium — and including similar moves to Milwaukee, Minneapolis, Oakland, and Arlington (Texas), Kansas City’s arrival as a major-league squad was largely due to possession of a suitable stadium, or at least one that could be rebuilt into one. These multi-use structures, which also housed pro football teams and other community events, reshaped the professional sports landscape in America in the years after World War II. Under whatever name was in use at the time, Kansas City’s Ruppert Stadium was at the vanguard of that movement.

However, as is often the case, all good things must come to an end. The ballpark was torn down in 1976, and a community garden currently stands on the site.41

Editor’s Note

The ballpark at 22nd and Brooklyn in Kansas City was known as Muehlebach Field from 1923 to 1937, named for owner George E. Muehlebach of the minor-league Kansas City Blues, who built the original structure. When the New York Yankees owned the franchise and ballpark (1938-42), it was renamed Ruppert Stadium for Yankees owner Jacob Ruppert, but when Ruppert died it was renamed Blues Stadium (1943-54). When the Athletics relocated to Kansas City in 1955, and for the remainder of its existence, the building was named Municipal Stadium because of the heavy amount of public financing.

Because the 1942 Monarchs played in Ruppert Stadium, that is how it is identified in this article. The Monarchs played in the ballpark from 1923 through 1961. Negro League World Series games were played there in 1924 (Games Five through Seven), 1925 (Games One through Four), 1942 (Game Four), and 1946 (Games Three and Four).42

The architectural firm that oversaw construction of the park was Osborn Engineering.

Notes

1 Sam Mellinger, “Fifty Years Ago, Satchel Paige Pitched His Last Big-League Game in KC … at Age 59,” Kansas City Star, September 18, 2015. https://www.kansascity.com/sports/spt-columns-blogs/sam-mellinger/article35763006.html.

2 Mellinger.

3 Rob Neyer, “Satchel Paige’s Last Stand,” SBNation.com, September 25, 2013. http://sbnation.com/2013/9/25/4767976/satchel-paige-kansas-city-athletics-1965-oldest-mlb-pitcher.

4 Mellinger.

5 Brian Burnes, “Dreaming of Fields: A Brief History of Kansas City Ballparks,” KCFlatland.org, December 19, 2019. https://www.flatlandkc.org/news-issues/dreaming-of-fields-a-brief-history-of-kansas-city-ballparks/ Accessed May 13, 2021.

6 Larry Tye, Satchel — The Life and Times of an American Legend (New York: Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2009), 42-44.

7 Philip Lowry, ed., Green Cathedrals, fifth edition (Phoenix: Society for American Baseball Research, 2019), 159-161.

8 Janet Bruce, The Kansas City Monarchs — Champions of Black Baseball (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1982), 51-52.

9 Brian Burnes, “Dreaming of Fields.”

10 Lowry, 159-161.

11 Japheth Knopp, “Negro League Baseball, Black Community, and The Socio-Economic Impact of Integration,” SABR Baseball Research Journal, Spring 2016: 67, 68.

12 Jack Etkin, Innings Ago — Recollections by Kansas City Ballplayers of Their Days in the Game (Kansas City, Missouri: Normandy Square Publications, 1987), 10.

13 Bruce, 38-39.

14 Bruce, 38.

15 Bruce, 24-25.

16 Bruce, 24-25.

17 Etkin, 10.

18 “Kansas City Blues Franchise History (1888-1954),” https://statscrew.com/minorbaseball/t-kb12304. Accessed May 9, 2021.

19 Phil S. Dixon, The Dizzy and Daffy Dean Barnstorming Tour — Race, Media, and America’s National Pastime, (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2019), 55.

20 Flatlandkc.org; Jason Roe, “Kings of the City,” https://kchistory.org/week-kansas-city-history/kings-city. Accessed May 13, 2021.

21 Bill Jenkinson, “Babe Ruth and the Issue of Race,” BabeRuthCentral.com, 2009, updated 2016. https://baberuthcentral.com/babe-ruth-and-the-issue-of-race-bill-jenkinson. Accessed May 13, 2021.

22 Dixon, The Dizzy and Daffy Dean Barnstorming Tour, 55.

23 Bruce, 70-71. According to uni-watch.com, the concept of baseball under portable lighting was tested in a game between the Monarchs and Phillips University in Enid, Oklahoma, played under the portable lights in front of 3,000 fans. https://uni-watch.com/2019/04/20/let-there-be-lights/.

24 Bruce, 50-51.

25 Phil S. Dixon, John “Buck” O’Neil — The Rookie, The Man, The Legacy, 1938 (Bloomington, Indiana: AuthorHouse, 2009), 23.

26 Dixon, John “Buck” O’Neil, 36.

27 Dixon, John “Buck” O’Neil, 66.

28 Bruce, 51-52.

29 Lowry, 53-55, 103-105.

30 Ernest Mehl, The Kansas City Athletics (Henry Holt: New York, 1956), 57-121.

31 Mehl, 139-140.

32 Mehl, 142.

33 Mehl, 146-148.

34 Mehl, 179-180.

35 Lowry, 165-166.

36 Lowry, 165-166.

37 https://www.baseball-reference.com/teams/NYY/1939-schedule-scores.shtml

38 Bill Francis, “Hall of Fame Opened the Day of Lou Gehrig’s Final Game,” baseballhall.org. https://baseballhall.org/discover/gehrig-played-final-game-on-day-hall-of-fame-opened Accessed June 4, 2021.

39 Tye, 136-137.

40 Tye, 136-137.

41 Green Cathedrals, 162.

42 Green Cathedrals, 161.