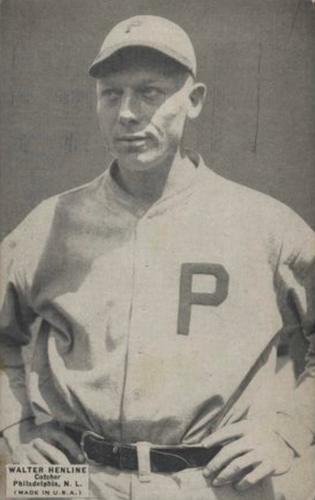

Butch Henline

On September 15, 1922, at the Baker Bowl in Philadelphia, the Phillies’ Butch Henline became the first catcher in major-league history to homer three times in one game. Each blow was critical as the Phillies came from behind to defeat the St. Louis Cardinals, 10-9. Twenty-six years later, Henline became the first umpire to eject Jackie Robinson from a big-league game. These two firsts constitute a parlay that is truly unique in baseball history. Henline’s journey from top-notch catcher for all or parts of 11 seasons (1921-1931) to respected arbiter for four (1945-1948) makes for a compelling story.

On September 15, 1922, at the Baker Bowl in Philadelphia, the Phillies’ Butch Henline became the first catcher in major-league history to homer three times in one game. Each blow was critical as the Phillies came from behind to defeat the St. Louis Cardinals, 10-9. Twenty-six years later, Henline became the first umpire to eject Jackie Robinson from a big-league game. These two firsts constitute a parlay that is truly unique in baseball history. Henline’s journey from top-notch catcher for all or parts of 11 seasons (1921-1931) to respected arbiter for four (1945-1948) makes for a compelling story.

Walter John Henline was born on December 20, 1894, in Fort Wayne, Indiana. His parents were Samuel Henline, a carpenter, and Caroline Mollett Henline, a homemaker. Walter was the third son, following George and Carl. Eventually two sisters, Esther and Florence, would join the brood.1 “Butch,” as his family called him, attended public school through the eighth grade.2

Henline began his baseball career as a 12-year-old pitcher for the youth league Fort Wayne Tigers. A cousin who managed the team converted him to a catcher when he was 14.3 A baseball fanatic, Henline spent many days chasing foul balls at League Park, home of the Fort Wayne Railroaders of the Class B Central League. This led to him being invited to catch batting practice for the team.4

About 1915, Henline took a job at the local Wayne Knitting Mill, which included an opportunity for the now 5-foot-10, 165-pounder to catch for the company baseball team. Noting Henline’s considerable ability, the knitting mill boss’s son, Otto Lutz, suggested that he try to play professionally. “You’ll make a lot more money than you will knitting socks,” Lutz told him.5

Henline took the tip. After writing to the manager of a Defiance, Ohio-based team, he was hired to play semipro ball for $25 dollars a game. In 1917, he played for the highly regarded Telling Strollers semipro club in Cleveland, where he hit .400.6 One day after work at the Telling factory, Henline stopped at a local restaurant to eat. The manager suggested that Henline “get into some regular league. [Future Hall of Famer] Larry Lajoie lives around the corner, I’ll give you his address.” Henline wrote to Lajoie and, two weeks later, he was given a minor-league contract for $200 a month.7

In 1918, Henline went to spring training with the Indianapolis Indians of the Class AA American Association. Lajoie was to be his manager but, with the United States having entered World War I, Henline was drafted into the army before the season began. In April, he reported to Fort Zachary Taylor in Louisville, Kentucky.

From Fort Taylor, Henline wrote to George Biggars, the sporting editor of the Indianapolis Star, about his army experiences. The paper published his letters, including a May 12 letter that said in part:

“Well, George this army life is a great life if one don’t weaken but there is a bunch of guys keeling over from it. Well, I got a non-C officers job [drill sergeant] the third day so that ain’t so bad for a starter.

I run the baseball club here and I have Schrader from the St. Louis club pitching for me and take it from me these officers down here sure are glad that I am catching for there (sic) team as I am going like a house afire down here. I have hit two home runs since I have been here, and one was today…I sure cocked it and you ought to see the officers give me the handshake after the game.

I got it soft George. I only drill about two hrs a day and the rest of the time I play ball so it ain’t so bad. The only thing is I have to get up at 6:45, but that will come easy after you are here a while. Well, I thought this might help you with your Newspaper and if you want a real story to put in why let me know and I will give you one.”8

Two weeks later, Henline wrote:

“Well, Geo. We lost our first game Wed the 26th to the 5th Battalion and it sure was sad in the ninth as we had a chance to win the game and some of my” players when they got on in the ninth run the bases like a wild horse trying to get one run over when we were 5 runs behind and I told them to watch thereself (sic) but you know how it is when a mule won’t drink water.”9

Biggars compared Henline’s style to that of famed baseball writer Ring Lardner.10

Following his discharge from the army, Henline started the 1919 season with Indianapolis. But, unable to displace starting catcher Dick Gossett, he was sold to the Bloomington (Illinois) Bloomers of the Three-I League at the end of May.11 (Bloomington infielder Heinie Sand would later be Henline’s Phillies teammate for four years.) Henline played well for the Bloomers, hitting .298 in 108 games. A notable chatterbox on the field and off, Henline caused some consternation in the press with his colorful language. An editorial in the Evansville (Indiana) Press complained that when Henline crossed the plate with the winning run on August 29, he shouted to the crowd, “There goes your —— —— ball game.” The paper demanded that Three-I League president Al Tierney take action to stop this “unsportsmanlike” and “ungentlemanly” behavior.12

In 1920, Henline became Indianapolis’ regular catcher. In 131 games, he hit .294. New York Giants manager John McGraw noticed his energetic play behind the plate and solid stick work. In September, Indianapolis sold Henline to the Giants for cash and two infielders, Fred (King) Lear and Doug Baird.13

In March 1921, Henline reported to San Antonio, Texas for spring training with the Giants. He objected publicly when he was placed on the second team. As the Pantagraph of Bloomington, Illinois reported, “Henline declares he should have been placed on the first team instead of Alex Gaston.14 He’s a peppery kid and possibly talks too much for his own good.”15 Henline stuck with the Giants long enough to get one regular season at-bat. He made his major-league debut on April 13 as a pinch-hitter. Facing veteran Jimmy Ring of the Phillies, he struck out. On April 24, the Giants optioned Henline back to Indianapolis.

On July 25, the Giants traded Henline, outfielder Curt Walker, and $30,000 to the Phillies for Irish Meusel. The Giants got the player they wanted. The slugging Meusel would help lead them to the 1921 World Series championship. The Phillies got a very serviceable outfielder in Walker. Phillies owner William F. Baker received an infusion of money for his perpetually cash-strapped team. Henline, 26, got a chance to be a major-league catcher.

Henline was an immediate hit with the Phillies. He made his first start on August 9 and caught most of the remaining games. His work behind the plate was said to remind longtime Phillies fans of Bill Killefer of Philadelphia’s 1915 pennant winners.16 On the last day of the season, Henline recorded three hits to raise his average with Philadelphia to .306.17 The Phillies thought enough of his ability that they sold incumbent starter Frank Bruggy to Portland of the Pacific Coast League.18

Nineteen-twenty-two would prove to be Henline’s finest year in the major leagues. The Phillies climbed out of the cellar for the first time in four years, although mostly because they were just a little less awful than the Boston Braves who lost 100 games. Henline was one of the team’s steadiest performers, however.

On May 31 at Baker Bowl, he turned in a typically stellar performance against his former team, the Giants. His solo home run off Rosy Ryan in the fifth inning evened the score, 1-1. In the bottom of the eighth, with the score still tied, Henline led off with a single and scored the lead run on a Cy Williams hit. Philadelphia led, 3-1, with one out in the top of the ninth, when Henline and Curt Walker pulled off a remarkable game-ending double play. With Heinie Groh on third base and Ross Youngs on second, the Giants’ High Pockets Kelly launched a high drive to right field. Walker snagged the ball with his back against the fence, a short 280 feet away, After Groh tagged up and headed for home, Henline caught Walker’s throw while dropping to one knee to block the plate and swiped a tag on the sliding runner. Game over.

On September 15, Henline had his three-home run game. The Phillies trailed the Cardinals, 7-0, in the fourth inning before his three-run shot off Epp Sell. In the seventh, Philadelphia was down, 9-6, when Henline’s two-run homer off Bill Doak brought them within a single run. The score remained, 9-8, entering the bottom of the ninth, but Henline took Bill Sherdel deep to tie the game. The next hitter, Cliff Lee, made it back-to-back homers, and the Phillies walked off with an improbable victory, 10-9.

Henline’s three circuit clouts were among six overall hit by both teams during the game. In addition to Henline’s and Lee’s blasts, Rogers Hornsby hit two homers for the Cardinals. The fireworks display, coming just two years into the Live Ball Era, prompted this headline in the Philadelphia Inquirer the next day, “Home Run Hitting in the Major Leagues Is Becoming a Farce.”19 Farce or not, the performance wrote Butch Henline’s name into the record books.

After that game, Henline began to garner national headlines. The Washington Times noted, “In Butch Henline the Phillies have a catcher who is a real drawing card. In throwing and generalship there are few catchers who can match Henline. In batting there is not another receiver in the nation who can tie him.”20 For the season, Henline hit .316 with 14 home runs and 64 RBIs in 125 games. His .983 fielding percentage led National League backstops. The United Press named him the “outstanding young player of the year.”21

Even the parsimonious Phillies owner had to recognize Henline’s ability and popularity. In January 1923, William F. Baker signed his star catcher to a $12,000 a year contract.22 Henline responded by hitting .324. Despite the big contract and continued solid production, however, Henline began to see his playing time reduced. He started 119 games behind the plate in 1922, 96 in 1923, 82 in 1924, 68 in 1925, and 76 in 1926. The main reason for this appears to be the arrival of Jimmie Wilson, whom the Phillies purchased from New Haven in the Eastern League in February 1923. Wilson was several years younger than Henline and a superior defensive catcher. They began sharing catching duties, and Wilson eventually became the primary starting catcher.

In October of 1923, Henline married Marguerite Miller of Bloomington, Illinois, whom he had met when he was playing for the Bloomers. Henline told The Sporting News editor, J.G. Taylor Spink, about a hot day in 1919, when rain halted play and he said to a teammate, “Gee, I wish I had a Coke.” Suddenly, a batboy appeared with a Coke for Henline, explaining that it had been sent over by a young woman sitting in a car outside the fence. Henline sent the batboy back with a note of thanks, including a request for a date. She accepted. Her name was Marguerite Miller.23

Despite his reduced playing time, Henline continued to be a productive player, generally hitting close to .300 each year. Manager Art Fletcher chose the popular and loquacious Henline to be the Phillies captain in 1925. Henline celebrated the appointment by leading Philadelphia to victory over the Brooklyn Dodgers in the Phillies’ home opener, banging out two triples and a single in a game the Phillies hung on to win, 8-7.

Henline was a holdout in 1926, and his failure to report cost him his captain’s position with the Phillies. After he signed, he continued to share catching duties with Wilson and had another solid year, hitting .283 in 99 games, though his power numbers were down. With the younger Wilson thriving, however, it was just a matter of time before Henline was moved. The trade happened on January 9, 1927. It was a three-way deal that saw Henline briefly become property of the Giants again, before ending up with the Brooklyn Robins. He was immediately penciled in as the starting catcher for Wilbert Robinson‘s team.

Writing in the Yonkers Herald, sportswriter Dan Daniel could not contain his enthusiasm over the trade. “Henline embodies what many critics regard as the ideal factors of catching, effectiveness as a backstop, effectiveness as a hitter, and the ability to hold up a pitcher. There isn’t a more talkative player in the majors.”24 For his part, Henline was “tickled pink.” As he told the Brooklyn Times Union, “You can’t imagine what playing in Brooklyn means to me. I have been dissatisfied with the conditions in Philadelphia for the last five years. I hope I catch every game for Robby.”25

It didn’t work out that way. Henline struggled to find his batting stroke in spring training, and the hitting woes continued into the season. He ended up splitting catching duties with Robin’ holdovers Hank DeBerry and Charlie Hargreaves. Henline started only 50 games behind the plate and hit a career low .266. His defense suffered as well. Henline developed what was described as “sciatica” in his throwing arm and had difficulty throwing to bases. On May 18 against the Chicago Cubs at Ebbets Field, he made three throwing errors that led to four unearned runs in a 7-4 defeat. On June 29, a particularly embarrassing miscue occurred against his former team, the Phillies, at the Baker Bowl. With the game on the line, Henline dropped a “perfect throw” from left fielder Gus Felix allowing the winning run to score.26

Over the next two years, Henline’s decline continued with the Robins. He hit .212 while starting 35 games in 1928, and .242 in 15 starts in 1929. He was waived and sent to the Toledo Mud Hens of the American Association. After an outstanding 1930 season at Toledo in which he hit .347 in 103 contests, the Chicago White Sox purchased his contract. He appeared in three games for the club that September and 11 more in 1931 before he was released to Toledo in July.

Henline remained with the Mud Hens until June 1933, when he moved on to the Minneapolis Millers in the same circuit. He split 1934 between two teams in the Class AA International League, the Montreal Royals and the Baltimore Orioles. After sitting out 1935, Henline tried one more comeback with the Hopkinsville (Kentucky) Hoppers of the Class D Kentucky-Illinois-Tennessee League in 1936. But the 41-year-old soon realized it was time to call it a career. In the majors, he finished with a .291 batting average and 40 homers in 740 games.

In retirement, Henline and his wife purchased the lease on a hotel in Sarasota, Florida. The business was doing well, but he wanted to get back into baseball. Many years before, legendary umpire Bill Klem had told Henline he would make a good umpire after his playing days were over. Henline was umpiring for a local softball league for $2.50 a game when some former major-league friends saw him work and encouraged him to pursue it professionally. Henline went to umpiring school and began his new career in the Class B Southeastern League in 1939. His good work earned him a promotion to the International League, where he worked from 1940-1944. In the fall of 1944, he was hired by Klem, by then the National League’s umpiring supervisor. Klem told Henline that, as a former catcher, he had the necessary experience to call balls and strikes that few others shared.27

On April 17, 1945, Henline debuted in Boston as the third-base umpire in the Braves’ Opening Day loss to the Giants. Two days later, in his first home-plate assignment, the Braves beat the Giants in the second game of a doubleheader, 13-5. In 1946, at Klem’s request, Henline umpired two youth all-star events: Brooklyn Against the World at Ebbets Field,28 and the Hearst Sandlot Classic at the Polo Grounds.29 Midway through his third season, Henline was one of four umpires for the 1947 All-Star Game, a 2-1 American League victory attended by 41,123 at Wrigley Field.

In August of 1948, Henline made national headlines by becoming the first umpire to toss Jackie Robinson from a game. Robinson responded to the ejection by saying, “Well, I broke in tonight.”

Henline gave this account of the incident:

“The Dodgers started in on me early. Robinson kept complaining when he knelt in the on-deck circle in the third inning. I warned him to cut it out. When I chased Bruce] Edwards in the top of the fourth for heckling, I warned the Dodgers on the bench also. Then I detected Robinson’s voice and out he went.”30

After he was thumbed, Robinson came out of the dugout to continue the discussion. Pittsburgh Post-Gazette sportswriter Al Abrams published Robinson’s account of that confrontation:

Henline: “I don’t want you yelling at me about balls and strikes.”

Robinson: “What are you talking about? I didn’t say anything.”

Henline: “I thought you did. You guys won’t let me umpire. You guys are always getting on me.”

Robinson: “Well, somebody should get on you.”31

At that point, coach Clyde Sukeforth came out to keep Robinson from getting into further trouble. Henline also dismissed Sukeforth from the game.

The ejections took place before the largest crowd of the season at Forbes Field in Pittsburgh-38,265. The Sporting News reported that the crowd included “7,500 Negroes”32 who came especially to see Robinson play. Players from both teams credited Henline for having the “intestinal fortitude” to eject Robinson. Some players pointed out that while Robinson always said he wanted to be treated like any other player, the umpires seemed to let him get away with quite a bit, including one incident where he threw his hat, which was usually an automatic ejection.33

After the season, Henline and his wife were feted in Sarasota by 60 friends on their 25th wedding anniversary. Paul Waner, Heinie Manush, Wes Ferrell, and Roy Spencer were among the former players in attendance. The joy was short-lived, however, as NL President Ford Frick announced in early December that Henline had been released from his umpiring contract. No reason was given for the action. Later that month, the league announced that another former player, Lon Warneke, would replace Henline.

A story that appeared in the Cincinnati Enquirer after Henline’s death provided one clue to the circumstances that led to his dismissal. Henline frequented a Sixth Street bar and restaurant in Cincinnati that Frick had declared to be out of bounds for players and umpires, on the grounds that it was frequented by bookmakers. Henline, who was friendly with the owner, thought it was an unfair ban and continued to go there. That decision apparently cost him his umpiring job.34

In the hopes of getting called back to the majors, Henline took a job umpiring in the Class B Florida International League. He refused to talk about his dismissal, saying only, “That is an unpleasant experience I have written off.”35 He never did get another shot at the big leagues, but he did become the Florida International League’s umpire-in-chief until it folded in 1954.

Henline umpired for one season in the Dominican Republic before retiring to Sarasota and contenting himself with occasional officiating appearances at old-timers games. He also served on the faculty of the Sarasota Herald Tribune baseball clinic.36

In March 1957, Henline was working at the Sarasota Golf Course Driving Range when he was taken seriously ill. The diagnosis was cancer. He died seven months later, on October 9. He was 62. Henline’s cremated remains are interred at the Manasota Memorial Park in Bradenton, Florida.

Acknowledgments

The biography was reviewed by Malcolm Allen and Howard Rosenberg and fact-checked by Gary Rosenthal.

Sources

In addition to sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted baseball-reference.com, retrosheet.org, and sabr.org/bioproject.

Notes

1 1910 United States Census.

2 1940 United States Census.

3 J. G. Taylor Spink. “Looping the Loops,” The Sporting News, June 28, 1945: 2.

4 Spink.

5 Spink.

6 “Bronkie’s Patched Up Team Awaits Mobile,” Indianapolis News, March 29, 1918: 22.

7 “Obituary,” The Sporting News, September 9, 1957: 34.

8 “‘Butch’ Henline Wins Over Ring Lardner with This One,” Indianapolis Star, May 12, 1918: 32.

9 Henline Can’t Get His Men to Run the Bases to Suit Him; That’s Why the Game Was Lost,” Indianapolis Star, May 19, 1918: 35.

10 “‘Butch’ Henline Wins Over Ring Lardner with This One.”

11 “Baseball Stories,” Kenosha (Wisconsin) News, May 24, 1919: 12.

12 “A Sport Editorial – On Butch Henline,” Evansville (Indiana) Press, August 30, 1919: 6.

13 “Butch Henline Is Sold to the Giants,” Evansville (Indiana) Journal, September 18, 1920: 1.

14 Henline may have been right. Gaston played in only 20 games for the Giants in 1921 and hit .227.

15 “Butch Henline Is Real Peeved,” Daily Pantagraph (Bloomington, Illinois), March 23, 1921: 10.

16 “The Insider Says,” Rock Island (Illinois) Argus, September 2, 1921: 20.

17 Henline scored the tying run in the ninth as the Phillies came from behind to defeat the Giants, 10-9.

18 The Bruggy transaction caused a lot of consternation in the press. Bruggy had performed well for the Phillies in 1921, hitting .310. The sale brought a record price from a minor-league team purchasing a major leaguer, $6,500. Many speculated that Phillies owner Baker was selling off another player to bring more cash into his coffers, without regard to the quality of the team he put on the field. “Sale of Bruggy Surprises Fans,” Evening Public Ledger (Philadelphia), January 9, 1922: 19.

19 Joe Vila, “Home Run Hitting in Major Leagues Is Becoming a Farce,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 16, 1922: 14.

20 “Butch Henline Is Big Drawing Card for Phils,” Washington Times, September 19, 1922: 16.

21 “Old-Timers Continue to Set Fielding Pace for Major Leagues,” St. Louis Star, December 24, 1922: 24.

22 Maurice Davis, “Sport,” Decatur (Illinois) Herald, January 21, 1923: 22.

23 Spink.

24 Daniel M. Daniel, “Walter (Butch) Henline Greatest of All Brooklyn Catchers in Dodger History,” Yonkers (New York) Herald, February 8, 1927: 17.

25 Thomas W. Meany, “Butch Henline, In Town to See Robby, Pleased with Deal,” Times Union (Brooklyn, New York), February 5, 1927: 9.

26 “Philadelphia Fans Make Merry as Butch Henline Tosses Game,” Brooklyn Citizen, June 30, 1927: 8.

27 Spink.

28 “Big League Umps to Work Star Tilt,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 27, 1946: 6.

29 “Burrows Puts ’Em Ahead but U. S. Stars Lose,” San Antonio Light, August 16, 1946: 6A.

30 Les Biederman, “In Big League Now, Says Robinson After First Thumbing from Field,” The Sporting News, September 1, 1948: 16.

31 Al Abrams, “Robinson Gets Chased First Time in Majors,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, August 25, 1948: 14.

32 Biederman.

33 Biederman.

34 Al Shottlecotte, “Talk of the Town,” Cincinnati Enquirer, October 15, 1957: 5.

35 Jimmy Burns, “Henline Likes Spirited Play of Cubans in F—I,” The Sporting News, May 31, 1960: 38.

36 “Walter (Butch) Henline, Ex-Major Leaguer Dies,” Tampa Tribune, October 10, 1957: 47.

Full Name

Walter John Henline

Born

December 20, 1894 at Fort Wayne, IN (USA)

Died

October 9, 1957 at Sarasota, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.