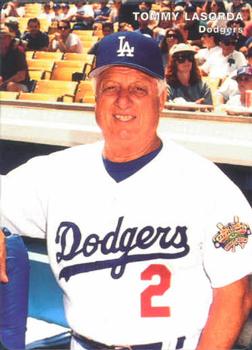

Tom Lasorda

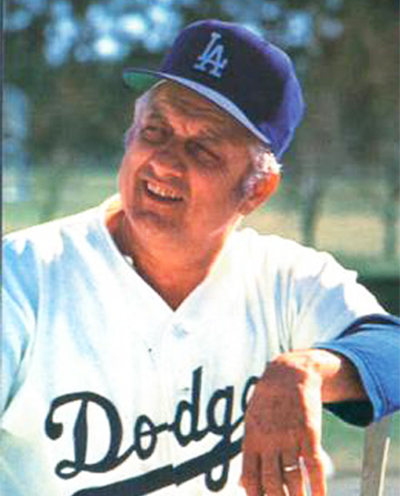

Tommy Lasorda. You could almost say he needs no introduction. Famous and familiar for his nearly 20 years as manager of the Los Angeles Dodgers, Lasorda was the personification of the Dodgers and baseball’s best-known ambassador. Profane or charming, pugnacious or proud, outrageous or simply outspoken, Lasorda could be all these and more.

Tommy Lasorda. You could almost say he needs no introduction. Famous and familiar for his nearly 20 years as manager of the Los Angeles Dodgers, Lasorda was the personification of the Dodgers and baseball’s best-known ambassador. Profane or charming, pugnacious or proud, outrageous or simply outspoken, Lasorda could be all these and more.

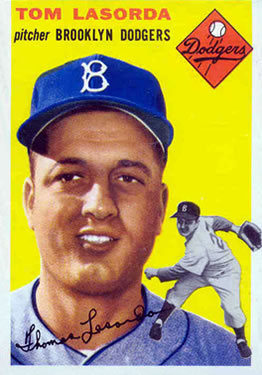

Lasorda’s major-league career was nearly as brief as that of his Dodger predecessor Walter Alston, who struck out in his only big-league at-bat. Lasorda compiled a record of 0-4 with the Brooklyn Dodgers and the Kansas City Athletics in the mid-1950s to go with his career 58 1/3 innings pitched.1 But despite an outstanding minor-league career, it wasn’t Lasorda’s pitching that would lead to his greatness.

Thomas Charles Lasorda was born in Norristown, Pennsylvania, just northwest of Philadelphia, on September 22, 1927. He was the second of five sons born to immigrants Sabatino Lasorda and his wife Carmella (Cavuto) Lasorda, both from Italy’s Abruzzo region. He was, by his own account, from a poor but proud family. Lasorda never played catch with his father – who was known as Samuel – and his father never taught young Tom to be a ballplayer, “but he taught him to be a man.”2 With a family of seven to feed, Lasorda’s father worked long hours as a laborer and truck driver at the local quarry. His mother was a homemaker who learned her cooking skills in her own Italian family.

Like others of his generation, young Tommy grew up in the Great Depression and worked numerous odd jobs to help the family financially, and he played baseball at every opportunity. For Lasorda, a potential baseball career was not only a dream but also a way to avoid working in the same quarry as his father.

Baseball became Lasorda’s passion and when he wasn’t working, the game was all-consuming. “When I wasn’t playing or talking baseball, or listening to a game, or reading about it, I was dreaming about it.”3

In addition to baseball, another skill Lasorda developed in his youth was fighting – not just brawling but boxing. He showed some promise as an amateur boxer and even had offers to turn professional.4 He declined a chance to box professionally, but his pugnacious personality arose during many pitching confrontations.

The left-handed Lasorda claimed he did not show enough promise to pitch for his high school team, and he described himself as a third-stringer. However, his high school yearbook is more complimentary and lists him as one of the two leading pitchers on the team.5 In 1944 his pitching and hitting helped lead the Norristown recreational league team to the “mythical junior baseball championship” against the Connie Mack All-Stars. Lasorda’s complete-game victory along with two hits got the attention of Philadelphia Phillies scout Jocko Collins who offered Lasorda $100 a month to play for the Phillies Class A club in Utica, New York.6 Lasorda signed a Utica Eastern League contract.7

In March 1945, at the age of 17, Lasorda reported for spring training with the Phillies in Wilmington, Delaware. After spring training, he reported to the Class D Concord Weavers in Concord, North Carolina — the beginning of Lasorda’s long but productive minor-league career.

While considered primarily a pitcher, Lasorda played regularly at first base. In one Concord game, Lasorda saw action as pitcher, first baseman, and right fielder.8

Lasorda’s Concord career was over after the 1945 season, where he had a 3-12 record and an ERA of 4.09.9 He was drafted into the U.S. Army, where he played baseball during 1946-47. He spent time at Fort Meade and Fort McClellan in 1946 and Fort Jackson in 1947.

In the spring of 1948, the Class D Kinston (NC) Eagles purchased Lasorda’s contract.10

Lasorda returned to the Phillies training camp and was assigned to their Class C affiliate in Schenectady, New York. Lasorda still had his “stuff” after his time in the Army and, on May 31 while pitching for the Schenectady Blue Jays, he struck out 25 batters in a 15-inning game11 and had 53 strikeouts over a three-game stretch.12 This performance got the attention of the Brooklyn Dodgers and changed the course of Lasorda’s life.

In November 1948, the Dodgers drafted Lasorda from the Phillies and sent him to the Greenville (South Carolina) Spinners of the Class A Sally League. With two brief interruptions, Lasorda spent the rest of his career – and life – with the Dodgers.

While playing at Greenville, Lasorda met a young local woman named Joan (Jo) Miller. Despite Jo’s initial reluctance, Lasorda was eventually able to persuade her to go out with him and to marry him.13 “He’s the most persistent person I’ve ever met,” Jo recalled years later, so persistent that he convinced her to give up her desire to become an airline hostess.14

After someone stole the money he had saved to get married, Lasorda, by then assigned to Montreal, asked General Manager Buzzie Bavasi for a $500 loan. Rickey thought married ballplayers were more stable and agreed to the loan.

Tom and Jo were married on April 14, 1950. Daughter Laura was born in 1952 and son Tommy Jr. in 1958.

In 1950, pitching with the AAA Montreal Royals, Lasorda picked up nine wins in his first season and accumulated 107 wins for Montreal, for whom he played in eight of the next 10 years. His total wins at the highest minor-league level reached 117 with both three victories for the American Association Denver Bears in 1956 and 10 wins with the Los Angeles Angels of the Pacific Coast League in 1957.

Lasorda had 20 shutouts with the Royals and was an International League All-Star on two occasions. Including his low-minors’ victories, Lasorda won 136 games in the minors.

After winning 14 games in 1952 and 17 more in 1953, Lasorda was Pitcher of the Year in the International League and an IL All-Star. Lasorda had 14 victories for the Royals by the end of July 1954 and at the age of 26 got called up by the Brooklyn Dodgers for his major-league debut.

Lasorda’s major-league debut occurred on August 5, 1954. He entered the game against the St. Louis Cardinals in the fifth inning with the Dodgers trailing 8–2. Lasorda gave up singles to the first two batters he faced but recorded a strikeout and double play to get out of the inning without giving up a run. He pitched three innings in his first game and gave up six hits and three earned runs.

Lasorda’s major-league debut occurred on August 5, 1954. He entered the game against the St. Louis Cardinals in the fifth inning with the Dodgers trailing 8–2. Lasorda gave up singles to the first two batters he faced but recorded a strikeout and double play to get out of the inning without giving up a run. He pitched three innings in his first game and gave up six hits and three earned runs.

For the season Lasorda pitched nine innings over four games in relief without a decision.

Lasorda started the 1955 season with the Dodgers and got his first start on May 5 against the St. Louis Cardinals. He struck out Stan Musial but also unleashed three wild pitches.15 After the third wild pitch, Lasorda was blocking home plate in an effort to stop Wally Moon from scoring. Moon scored and cut open Lasorda’s knee in the process. Lasorda finished the inning, but the injury forced him to leave the game – after one inning.

Later in the season, the Dodgers sent Lasorda back to Montreal to make roster space for Sandy Koufax. As Lasorda related it:

[General Manager] Buzzy Bavasi called me into his office. “We have a roster problem,” he explained, “we’ve got to cut somebody. It’s a tough decision, there are a lot of outstanding players on this club. . . .” Buzzy and I were the only people in that room, and I knew he wasn’t going to get cut. I had the feeling he was trying to tell me something.

“. . . lemme ask you,” he continued, “if you were me, who would you cut?”

I didn’t hesitate. No matter how angry I was, I wanted to see the Dodgers win. “Koufax,” I said, “That kid can’t win up here.” The Dodgers had recently signed a left-handed pitcher out of the University of Cincinnati named Sandy Koufax. He could throw hard, but he had absolutely no control. I knew he couldn’t help the team.

Buzzy shook his head. “We’ve gotta keep him,” he said. “Tommy, we’ve gotta send you out. I’m sorry.”16

Lasorda did get one more big-league opportunity after being traded to the Kansas City Athletics before the 1956 season. In 18 games, he pitched 45 1/3 innings and compiled an 0-4 record. During his brief Kansas City tenure, he surrendered the first home run to future great Luis Aparicio.17 Though the 1956 season marked the end of Lasorda’s major-league career, he continued to pitch in the high minors for five more seasons, first with the Denver Bears (of the Yankee organization) and then finishing in Montreal. At Denver, Lasorda played for future Yankee manager Ralph Houk.

Back with the Dodger organization in 1960, scouting director Al Campanis approached Lasorda about becoming a full-time scout. Though disappointed that his pitching career seemed to be over, he took the job of scouting in the six-state mid-Atlantic area. By 1963, Lasorda had been named a Dodgers scout for southern California. In four years as a scout, Lasorda is credited with discovering, scouting, or signing Willie Crawford, Tom Hutton, and Jim Strickland. In addition to scouting, he would occasionally conduct Dodger tryout camps. While Lasorda had his share of successes, two players he claimed to have tried but failed to sign were Rick Monday and Tom Seaver.18

In 1965, Lasorda’s time as a scout ended when the Dodgers asked him to manage their rookie- league team, the Pocatello Chiefs, in Pocatello, Idaho. In his first stop in the Pioneer League, the Chiefs tied for second place. Lasorda next moved to Ogden, Utah, also of the Pioneer League. He guided the Ogden Dodgers to three straight pennants.

Several future stars came through Ogden while Lasorda was manager, including Bill Russell, Charlie Hough, Steve Garvey, and Bobby Valentine.19

It was as a manager in the low minors that Lasorda earned his reputation as a motivator, as an unabashed supporter of the Dodger organization, and as a manager who tried to be a friend to his players. His success in Ogden proved this approach to be a winning strategy.20

By the end of 1968, Campanis was Vice-President, Player Personnel and Scouting, of the Los Angeles Dodgers. One of Campanis’s early moves was to promote Lasorda to manage the AAA Spokane Indians of the Pacific Coast League. Spokane won 71 games and lost 73 in Lasorda’s first year. But in 1970 the Indians finished with a 94-52 mark and ran away with the Northern Division title. They proceeded to beat the Southern Division champion Hawaii Islanders in the playoffs to win the PCL pennant. Lasorda was named Minor League Manager of the Year by The Sporting News.21

The Spokane roster in the early 1970s was much like the Dodger roster a few years later. In addition to the core players from the Ogden team, the Indians had Tom Paciorek, Joe Ferguson, Davey Lopes, and Ron Cey. And in 1971, Lasorda signed Hoyt Wilhelm after the Atlanta Braves released the veteran knuckleballer. Wilhelm pitched in eight minor-league games before the Dodgers decided he was still good enough to pitch in the majors and signed him as a free agent on July 10, 1971.

After the 1971 season, the Dodgers established the Albuquerque Dukes as their AAA affiliate. Lasorda concluded his minor-league-managing career by leading the Dukes to a 92-56 record and the Eastern Division title in 1972. Albuquerque defeated Western Division winner Eugene in the best-of-five playoff, 3-1, to win the PCL pennant.

Lasorda’s minor-league success from the lowest to the highest levels finally earned him a promotion to the majors in 1973 – not as a manager but as a coach for the Los Angeles Dodgers. Beginning in 1973, Lasorda was the third-base coach for the Dodgers under manager Walter Alston. Despite their vastly different styles and personalities – quiet and serious versus loud and outgoing – they worked well together. As Lasorda himself put it: “The thing I did best for Walter was help create a loose, happy ball club. . . . Laughter is food for the soul, and I wanted any team I was with to be as well fed as I was.”22

Despite his comments, Lasorda’s relationship with Alston was not always smooth. Lasorda resented what he thought was Alston’s refusal to give him a chance to prove himself in his playing days with Brooklyn in 1954 and 1955. And he hated that Alston occasionally had him sit in the dugout instead of the bullpen to better cheer on his teammates. But like Lasorda, Alston agreed “that the best managers weren’t afraid to be close to players.”23

As third-base coach from 1973-76, Lasorda pitched batting practice, encouraged players, and helped create a positive atmosphere in the clubhouse. He was frequently mentioned as a manager prospect for various teams. But Lasorda stuck with the Dodgers and, as the 1976 season was winding down, Alston announced his retirement. At 49 years of age, Lasorda had his dream job – manager of the Los Angeles Dodgers.

The Los Angeles Times reported that “Thomas Charles Lasorda, third-base coach for the last four summers, the man who bleeds Dodger blue, who prays to the great Dodger in the sky, who has spent 28 years with the organization as pitcher, scout, minor league manager, major league coach and believer in the cause, was selected Wednesday to succeed Walter Alston as manager.”24

Managing the final four games of the 1976 season, Lasorda recorded two wins and two losses.

Lasorda’s managerial philosophy was formed during his years in the minors. From Greenville manager Clay Bryant in 1949, Lasorda learned what he did not want to be. Bryant “treated his players like cattle . . . that they were little parts of a giant machine.’’25 Bryant was cold, stoical and feared by his players. When he got his chance, Lasorda vowed to do things differently. Coincidentally, Bryant was Lasorda’s last manager at Montreal before Lasorda ended his playing career in 1960.

A positive model for Lasorda was Ralph Houk, manager of the Denver Bears during Lasorda’s brief tenure there in 1956. After a disastrous first outing for the Bears, possibly because his curveball failed to break in Denver’s thin air, Houk treated Lasorda with kindness and encouragement. “Ralph taught me that if you treat players like human beings, they will try to play like Superman,” Lasorda recalled.26 It was a plan Lasorda followed throughout his career as a manager.

Additionally, Lasorda identified his players’ skills and encouraged them to focus on their strongest skills. In 1977 asked Steve Garvey and Dusty Baker to try to hit more home runs. In the minors, Lasorda encouraged Charlie Hough to give up being a third baseman and was the manager when Hough learned the knuckleball from Goldie Holt.

Lasorda was especially good at organizing and maximizing the output of his starting rotation. Befitting a pitcher of his era, he depended heavily on his starting pitching and spent less time assembling a functional bullpen.

Dodger players, many of whom had been with Lasorda for years in the minor leagues, were all supportive of his selection as manager. Bill Buckner noted that “Tommy is an aggressive manager. He likes to make moves and make the opposition make mistakes.” Ron Cey called him “the most qualified man to assume the manager’s post.” Others like Tommy John, Steve Garvey, and Davey Lopes were also happy with the selection of Lasorda as manager.27

The 1977 Dodgers were a very good team and poised to displace Cincinnati’s Big Red Machine atop the National League. Longtime Lasorda friend Frank Sinatra got things going by singing the National Anthem on Lasorda’s first Opening Day as a manager.

The Dodgers won 22 of their first 26 games under Lasorda, and by mid-May they held an 11-game lead over the Reds. They never looked back and were in first place in the National League’s Western Division for virtually the entire season (Houston led the Dodgers from April 11 through April 14). Part of the success can be credited to a historic first for the Dodgers. They had four different players with 30 or more home runs on the season: Steve Garvey, Reggie Smith, Ron Cey, and Dusty Baker.28 But it wasn’t just hitting that led to the Dodgers’ success. The five starters – Don Sutton, Tommy John, Rick Rhoden, Burt Hooton and Doug Rau – each threw over 200 innings that season.

Next up were the Philadelphia Phillies in the League Championship Series. After dropping the opener, the Dodgers won the next three games to claim the pennant in Lasorda’s first full season as manager. A World Series matching the Dodgers and Yankees for the first time since 1963 followed. Aside from a renewal of the famous Subway Series of the 1940s and 1950s, an interesting subplot was a rivalry between Lasorda and Yankee skipper Billy Martin that stretched back more than 20 years.29 The Dodgers managed only two wins in the Series, highlighted by Reggie Jackson’s three home runs on three pitches in the sixth and final game. The loss was a bitter disappointment for the Dodgers, but in typical Lasorda fashion, Lasorda said, “As I told my team, next to winning the World Series, the best thing that could happen to a team was losing the World Series.”30

The 1978 season would provide the Dodgers and Lasorda with another chance to win the World Series, though they once again fell short. It looked like a repeat of 1977 as the Dodgers edged out the Reds for the division title, then ousted the Phillies in the League Championship Series in four games. In the LCS, Steve Garvey hit four home runs against Philadelphia and Tommy John hurled a timely shutout to set the Dodgers up for a rematch against the Yankees in the World Series.

In another six-game series the Dodgers won the first two games at home but then dropped four straight games to the Yankees to face another long winter.

In Game Two, Lasorda brought in Bob Welch to face the Yankees in the ninth inning. Welch entered the game with two runners on base and one out. He got Thurman Munson to fly out and then struck out Reggie Jackson to end the game. It was a small moment of satisfaction for the Dodgers but passed quickly as the Series moved to New York. Ron Guidry and Jim Beattie had complete game victories and Graig Nettles had several memorable defensive plays.31

In 1979 the Dodgers finished under .500 for one of the few times in Lasorda’s career but bounced back in 1980 to tie the Houston Astros for the division title on the last day of the season. The Dodgers won three in a row from the Astros to force a one-game playoff, but the Dodgers were out of answers. Joe Niekro threw a complete game while giving up no earned runs, and Houston earned its first division title, 7-1.

As they used to say in Brooklyn, “Wait till next year.” For Lasorda and the Dodgers, 1981 provided the perfect cure. A shortened season due to a players’ strike and an extra round of divisional playoffs pitting the first half and second half division winners against each other heightened the drama.

As they used to say in Brooklyn, “Wait till next year.” For Lasorda and the Dodgers, 1981 provided the perfect cure. A shortened season due to a players’ strike and an extra round of divisional playoffs pitting the first half and second half division winners against each other heightened the drama.

Facing the Astros in a best-of-five series, the Dodgers lost the first two games on the road. But in LA the Dodgers came to life to win three straight games behind outstanding pitching from Burt Hooton, Fernando Valenzuela, and Jerry Reuss.32

Next up were the Montreal Expos in the NLCS. The teams split the first two games in Los Angeles and then headed to Montreal. Lasorda had some concerns about the cold weather in Montreal on October 16, yet insisted that his players not wear warm up jackets during introductions.33 The psychological ploy did not have the desired results as the Dodgers lost Game Three. Facing elimination, the Dodgers won Game Four, 7-1, behind the pitching of Hooton, Welch, and Steve Howe, and a late homer from Garvey. In the fifth and deciding game, Valenzuela pitched 8 2/3 outstanding innings, and Rick Monday hit a clutch ninth-inning home run to return the Dodgers to the World Series.

For the third time in five years, the Dodgers faced the Yankees in the World Series. The Yankees won the first two games in New York – just as the Dodgers had won the first two games in LA in the 1978 Series. Now faced with the same dilemma that had worked out so well for the Yankees three years earlier, Lasorda remarked, “Seems to me, we’ve got them right where we want them.”34

Valenzuela started the crucial third game for the Dodgers. It was the season of “Fernandomania” in Los Angeles. The Yankees got four runs in the first four innings (two in the second and two in the third) to take a one-run lead. “Traditional strategy called for me to take him out, but I just couldn’t,” Lasorda later recalled. “This is the year of Fernando.”35 Lasorda, who was frequently criticized for managing as much on emotion as strategy, left Valenzuela in for the entire game, and 146 pitches, as the Dodgers held on for a 5-4 victory.36

The next day the Dodgers overcame an early four-run deficit to even the Series at two games each. Welch started for the Dodgers and gave up three hits, a walk, and two runs in the top of the first. Lasorda was forced to take out his starter before he had gotten anyone out. Still the Dodgers fought back and eked out the win, 8-7, partly on the strength of a Jay Johnstone pinch-hit home run.

Lasorda turned to Reuss in the fifth game. Reuss scattered five hits in a complete game, 2-1 victory. The Dodgers were one win away from the championship. Game Six was back in New York as Hooton faced Tommy John. In a key move that was likely a combination of traditional strategy and gut instinct, in the fourth inning Lasorda walked the Yankees number-eight hitter to get to pitcher John. Bobby Murcer pinch-hit for John and flied out. The Dodgers scored seven runs off John’s replacements. They coasted the rest of the way, winning the game 9-2, and the 1981 World Series four games to two.

For Lasorda, the championship could not have been sweeter. It was his first title with many players he had groomed for years. “It wasn’t just beating the Yankees, it was doing it with Garvey and Lopes, Russell, Cey, the people I had been with for so long,” Lasorda said. “We started together in the lowest minor leagues, and together we became world champions.”37

In 1982 the Dodgers finished one game behind division-winning Atlanta. For 1983, the team looked vastly different from the previous season as Garvey, Lopes and Cey had all departed. Lasorda earned his salary that year working with a younger team and frequent lineup changes. Lasorda’s main challenge was replacing most of the infield that had played together for so many seasons. But the squad found their way back to the top and once again faced the Phillies in the NLCS. The revamped team, featuring Greg Brock at first, Steve Sax at second, Russell at shortstop, and Pedro Guerrero at third, could manage only one win over Philadelphia in the playoffs.

After a disappointing 1984, the Dodgers showed their resilience by bouncing back in 1985 to win the Western Division by 5 ½ games over the Reds. Led by the hitting of Guerrero and the pitching of Orel Hershiser and Valenzuela, LA won 95 games and proceeded to the playoffs against St. Louis.

The league championship series was the best of seven, rather than the best of five, for the first time in 1985. After the Dodgers won the first two games in Los Angeles, the action shifted to St. Louis where the Cardinals won three straight. In the bottom of the ninth inning in Game Five, Ozzie Smith hit the only postseason home run of his career to break a 2-2 tie and carry the Cardinals to victory.

In Game Six, the Dodgers took an early 4-1 lead, but the tide turned in the seventh inning when Hershiser weakened and the score was suddenly tied at four. The Dodgers managed another run and still led 5-4 entering the ninth inning. With runners on second and third, Lasorda was faced with the decision of walking Jack Clark and facing Andy Van Slyke, or pitching to Clark. In one of the most second-guessed decisions of the era, Lasorda had Tom Niedenfuer pitch to Clark – who promptly hit a three-run homer. Losing the NLCS was a huge disappointment, but Lasorda later explained Niedenfuer had struck out Clark two innings earlier, and said, “man, did that hurt. That still hurts.”38

The next two seasons were out of the ordinary for both the Dodgers and Lasorda. In 1986 they fell to 73-89 and finished in fifth place, 23 games behind Houston. Valenzuela had a remarkable 20 complete games, 269 1/3 innings pitched, and 21 wins. In 1987 the Dodgers posted an identical won-lost record and ended the season 17 games back of the Giants. If there was a bright spot, it was the emergence of Hershiser as a skilled and, at times, dominant pitcher. Valenzuela again led the league in complete games, this time with 12.

The 1988 Dodgers surprised most observers by improving by 21 games to a total of 94 wins and claiming the division title by seven games over Cincinnati. The pitching staff recorded 32 complete games and 24 shutouts. Hershiser led the league with eight shutouts and 267 innings pitched. Along the way, Lasorda, who had entered the season with 928 wins as a big-league manager, won his 1,000th game with an August 21 win over the Expos.39

The Dodgers outlasted the New York Mets in a seven-game NLCS. Game Four was a critical win for the Dodgers as Mike Scioscia tied the game with a home run in the ninth, Kirk Gibson homered in the 12th inning to provide the winning margin, and Hershiser earned a save by recording the last out in the bottom of the 12th. The reward for the Dodgers was to face the powerful Oakland Athletics in the World Series.

The tone of the Series was set in Game One with a first-inning two-run homer by Mickey Hatcher. But the climax came in the bottom of the ninth when Lasorda brought in Gibson who hit a dramatic walk-off homer off Dennis Eckersley. The deflated A’s could muster only one victory as the Dodgers claimed the World Series championship in five games. For Lasorda it was his second championship as a manager.

Finally getting past the disappointment of 1985 and the criticism of his managerial style, 1988 marked the high point of Lasorda’s Dodger years. No one could question Lasorda’s action in imploring Hershiser to be the “Bulldog” and making him the ace of the pitching staff. And no one could question his decision to call on an injured Gibson to pinch-hit in the ninth inning of World Series Game One.

Lasorda had frequently been criticized for his in-game strategy, particularly his reliance on “small ball,” but a lot of that changed with the success of the 1988 team. According to the Los Angeles Times, “Maybe now, Lasorda’s managerial skills, obscured by his bombastic personality, will receive some attention. He has, after all, won 6 divisional titles, 4 National League pennants and 2 World Series championships in 12 seasons.” 40 For his efforts, Lasorda, in a poll of managers, shared National League Manager of the Year honors with Jim Leyland of the Pittsburgh Pirates. In addition, the Baseball Writers Association of America named Lasorda as Manager of the Year. Off the field, Lasorda arranged for the Dodgers to use a 62nd round draft pick in 1989 to select Mike Piazza. Done as a favor to Mike’s father, few anticipated the long-term results of the pick.41

Lasorda’s managerial career would last another seven and a half seasons but would never again reach the heights of 1988. In 1991 the Dodgers finished one game behind division-winner Atlanta. But in 1992 LA faded to a 63-99 record, last in the division – Lasorda’s worst finish ever.

The Dodgers narrowly won the realigned Western Division in 1994 and 1995 – Lasorda’s last full season. Following the cancellation of the 1994 postseason, the Dodgers faced the Reds in the 1995 NLDS. Cincinnati took three straight games and outscored the Dodgers, 22-7. It was not a high point in Lasorda’s postseason career but winning the division in his last full season showed that much of Lasorda’s abilities still survived.

Lasorda’s on-field career came to an end in 1996. On June 26 he underwent an angioplasty after suffering a heart attack. On July 29 Lasorda announced his retirement, and Bill Russell was named to replace him.42

In 1997 Lasorda was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame by the Veterans Committee. Shortly after his induction in Cooperstown, the Dodgers retired his uniform number 2. His Hall of Fame plaque includes the observation that he was “a great ambassador for his sport.” In addition to his other accomplishments, Lasorda won 1,599 games in the majors and the NL Manager of the Year awards in 1983 and 1988. At the time of his retirement his total of 61 postseason games managed ranked third all-time.

Even with these laurels, Lasorda was not quite finished. He returned as interim general manager of the Dodgers in 1998 after a front office shake-up. And in 2000 he was named manager of the U.S. Olympic baseball team, which won the gold medal in Sydney, the only United States Olympic team to ever defeat Cuba and claim the gold.43

Still, some parts of Lasorda’s legacy can overshadow his on-field career. He was notorious for fighting, particularly in his minor-league playing days, and he continued his combative nature as both a minor-league and a major-league manager. He was famously profane. As Bill Plaschke pointed out in his Lasorda biography, “Lasorda curses like Picasso once painted, applying the most colorful words with broad brushstrokes of his tongue, using a single invective as an adjective, adverb, verb and noun, all in the same sentence.”44 And, at times, his pride seemed to cloud his judgment.

One of the most sensitive and complex issues of Lasorda’s life was his relationship with his son Tommy Jr. – always called Spunky by his family. Spunky was gay. He died of complications from AIDS in June 1991 at the age of 33. By most accounts, father and son had a good relationship and spent much time together, especially at ballparks. But father Tommy refused to acknowledge that his son was gay and strongly denied that he died of AIDS. Some have even suggested that Lasorda Sr. was homophobic.

Writing in the Toronto Star in 2006 on the occasion of Lasorda’s selection to the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame, columnist Richard Griffin called Lasorda a “homophobic bully.” Griffin further noted that, according to Glenn Burke, Dodger center fielder in the late 1970s and the first openly gay player in the major leagues, manager Lasorda engineered a trade that sent Burke to the Athletics because he had befriended young Lasorda. In addition, according to Griffin’s column, Billy Bean alleges, even when young Lasorda was gravely ill with AIDS, his father continued telling “rough, unfunny, homophobic locker room jokes.”45

It is not clear whether Lasorda Sr. ever acknowledged that his son was gay or his cause of death. In an article from the Los Angeles Times at the time of Lasorda Sr.’s death, it is mentioned that he denied his son was gay in a 1992 GQ interview. But the same article refers to a verbal acknowledgement at a charity event in which the elder Lasorda said his son was gay and died of AIDS.46

It was no doubt a complicated personal issue for Lasorda who was conflicted by family loyalty and his strong religious beliefs. Two Lasorda biographies mentioned in this article contain only one passing reference to his son. Years after the deaths of both father and son, the whole story still seems rather complicated.47

Through it all, Lasorda embraced his role as a Los Angeles/Hollywood personality. He visited President Ronald Reagan in the White House and was photographed with President George H.W. Bush. His friendship with Frank Sinatra is well known, and Lasorda even invited comedian Don Rickles into the clubhouse to address the team.

But this high-profile lifestyle also would have unexpected consequences. When Sports Illustrated reported in 1986 that Lasorda was “hobnobbing openly” with Joe DiCarlo, the Dodgers denied knowing anything about his past. DiCarlo, also known as Peter DeCarlis, was reported by Sports Illustrated to be an associate of Mickey Cohen, an LA bookmaker and “organized crime figure” who died in 1976. DiCarlo was a regular visitor to Lasorda’s office at Dodger Stadium and frequently enjoyed seats behind the Dodger dugout. Joe DiCarlo is even listed as a Lasorda friend in the Acknowledgements section of the 1985 autobiography The Artful Dodger. Still, Lasorda said he knew nothing about DiCarlo’s background, and by all accounts made good on his vow to “not see [DiCarlo] anymore.”48

Lasorda continued as a special adviser to team owner and chairman Mark Walter in his later years. Lasorda suffered another heart attack in 2012 that required him to have a pacemaker. Even after turning 90 in 2017, Lasorda was never far from Dodger action. He was in attendance for the Dodgers’ World Series-clinching victory over the Tampa Bay Rays on October 27, 2020, their first title since 1988.

Lasorda died January 7, 2021, at the age of 93.49 He once commented that he wanted his epitaph to read: “Dodger Stadium was his address but every ballpark was his home.”50 His tombstone at Rose Hills Memorial Park in Whittier, California reads: “Once Met, Never Forgotten. A ‘Champ’ to All Who Knew Him.”

Acknowledgements

This biography was reviewed by Paul Proia and Howard Rosenberg and fact-checked by Tim Herlich.

Notes

1 Baseball-Reference.com; https://www.baseball-reference.com/bpv/index.php?title=Tommy_Lasorda&oldid=1166590.

2 Bill Plaschke and Tommy Lasorda, I Live for This (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Co., Mariner Books Div., 2009): 33.

3 Tommy Lasorda and David Fisher, The Artful Dodger (New York, Avon Books, a division of The Hearst Corp. and Arbor House Publishing Co., 1985): 9.

4 Lasorda and Fisher: 17.

5 Frederick E. Ruccius, ed., Spice (Norristown, Pennsylvania: Norristown High School, 1945): 102.

6 Philadelphia Inquirer, August 28, 1944: 14. Lloyd McGowan, “Lasorda Pitches, Coaches, Fills In as Manager,” The Sporting News, June 18, 1958: 29.

7 “Caught on the Fly,” The Sporting News, January 18, 45: 12.

8 Charlotte Observer, June 25, 1945: 10; Statesville (N.C.) Daily Record, June 27, 1945: 7.

9 Baseball-Reference.com; https://www.baseball-reference.com/bpv/index.php?title=Tommy_Lasorda&oldid=1166590.

10 The News and Observer (Raleigh, N.C.), April 18, 1948: 13.

11 Lasorda Fans 25 to Win 15-inning Can-Am Game,” The Sporting News, June 9, 1948: 34.

12 Lasorda’s 25 strikeouts in one game remained a professional record until Ron Necciai whiffed 27 in the Appalachian League in 1952. “Lasorda Living Large,” Buzzy Gray, Albany Times Union, July 27, 1997: E1.

13 Ross Newhan, “Lasordas’ Love Story, True Tale of Many Cities,” Los Angeles Times, May 6, 1978: 9.

14 Eric Lax, “Lasorda Took the Long Road,” Chicago Tribune, October 11, 1977: 47.

15 Three wild pitches in one inning tied the MLB record at the time. baseball-reference.com; https://www.baseball-reference.com/bpv/index.php?title=Tommy_Lasorda&oldid=1166590.

16 Lasorda and Fisher: 69.

17 Baseball-Reference.com; https://www.baseball-reference.com/bpv/index.php?title=Tommy_Lasorda&oldid=1166590.

18 Lasorda and Fisher: 146.

19 Plaschke and Lasorda: 103.

20 Gordon Verrell, “Lasorda Takes Dodger Reins,” Independent (Long Beach, California), September 30, 1976: 41.

21 Chuck Stewart, “Spokane’s Lasorda Chosen No. 1 Manager of Minors,” The Sporting News, December 5, 1970: 34.

22 Lasorda and Fisher: 228.

23 Plaschke and Lasorda: 62.

24 Ross Newhan, “Dodgers Get Their Man; It’s Lasorda,” Los Angeles Times, September 30, 1976: 42.

25 Plaschke and Lasorda: 53.

26 Plaschke and Lasorda: 85.

27 “Players Like Lasorda Pick,” The Desert Sun (Palm Springs, Calif.), September 30, 1976: 18.

28 Baker’s historic home run on the final day of the regular season is widely believed to have led to the first high-five in sports history as on-deck hitter Glenn Burke raised his open hand as Baker crossed home plate and Baker reached up to slap it. Also, “Glenn Burke Cut Down by Hypocrisy, AIDS,” San Francisco Examiner, June 1, 1995: 45.

29 During Lasorda’s brief tenure with the Kansas City Athletics, Yankee pitcher Tom Sturdivant had hit a couple of the A’s hitters. KC manager Lou Boudreau lamented that none of his pitchers would retaliate because “everyone was afraid of the Yankees.” True to form, Lasorda volunteered to pitch against the Yankees and promptly beaned two hitters, including Hank Bauer. Billy Martin, then a player with the Yankees, yelled to Lasorda. Lasorda yelled back and a fight erupted. According to reports, Martin charged Lasorda but was restrained by an umpire. Lasorda and Martin nonetheless remained good friends, including during the 1977 World Series. Bob Hertzel, “Lasorda, Martin 180 Degrees Apart,” Cincinnati Enquirer, October 11, 1977: 25.

30 Lasorda and Fisher: 261.

31 John Thorn, Phil Birnbaum and Bill Deane, Total Baseball, 8th Edition (Toronto: SPORT Media Publishing, 2004).

32 Thorn and Birnbaum.

33 Plaschke and Lasorda: 144.

34 Lasorda and Fisher: 273.

35 “Fernando Saluted for Gritty Job,” The Sporting News, November 7, 1981: 16.

36 Plaschke and Lasorda: 145.

37 Lasorda and Fisher: 293.

38 Plaschke and Lasorda: 141.

39 Baseball-Reference.com; https://www.baseball-reference.com/bpv/index.php?title=Tommy_Lasorda&oldid=1166590.

40 Sam McManis, “Lasorda Longtime Ringmaster of the Dodger Circus, Shows Critics of His Managing That He’s No Clown,” Los Angeles Times, October 24, 1988: Part VIII, 2.

41 Frank Fitzpatrick, “The Hall of Fame Manager Was One of Baseball’s Real Characters,” Philadelphia Inquirer, January 9, 2021. Page?

42 Thomas Bonk, “And Just Like That, 20 Years Slipped By,” Los Angeles Times, July 30, 1996: C1.

43 Josh Greene, “Hall of Famer Lasorda Manages Baseball’s Team USA,” Santa Cruz Sentinel, September 24, 2000: 97.

44 Plaschke and Lasorda: 11.

45 Richard Griffin, “Why Mr. Lasorda Shouldn’t Be in Our Hall of Fame,” The Toronto Star, June 25, 2006.

46 James Wagner, “Late Coach Had Tricky Bond With Gay Son,” from The New York Times as appeared in Dayton Daily News, January 14, 2021: E8. “The Biggest Game in Town,” Sports Illustrated, March 10, 1986: 33. “L.A.’s Lasorda Center of Gambling Controversy,” The Independent-Record (Helena, Montana), March 6, 1986: 17.

47 Peter Richmond, “The Brief and Complicated Death of Tommy Lasorda’s Gay Son,” Deadspin, April 30, 2013.

48 “The Biggest Game in Town,” Sports Illustrated, March 10, 1986, 33. “L.A.’s Lasorda Center of Gambling Controversy,” The Independent-Record (Helena, Montana), March 6, 1986: 17.

49 “Team Ambassador Lasorda Dies at 93,” The Spokesman-Review (Spokane, Washington), January 9, 2021: B1.

50 Lasorda and Fisher: 335.

Full Name

Thomas Charles Lasorda

Born

September 22, 1927 at Norristown, PA (USA)

Died

January 7, 2021 at Fullerton, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.