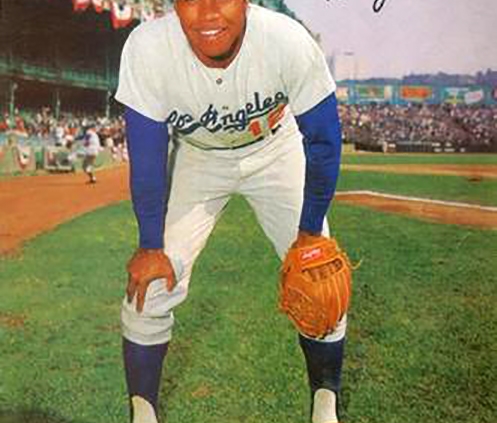

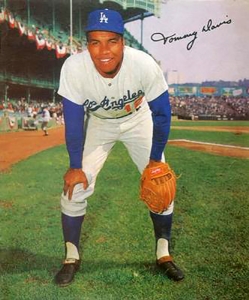

Tommy Davis

What Tommy Davis accomplished as a major leaguer on one good leg, most players would be proud to do on two. Not that this sums up his athletic career, but it is an important backdrop to his improbable baseball odyssey. Davis seemed ready to have his ticket punched for Cooperstown as he entered his ball-playing prime. An instant on the basepaths in 1965 took him down a very different road.

What Tommy Davis accomplished as a major leaguer on one good leg, most players would be proud to do on two. Not that this sums up his athletic career, but it is an important backdrop to his improbable baseball odyssey. Davis seemed ready to have his ticket punched for Cooperstown as he entered his ball-playing prime. An instant on the basepaths in 1965 took him down a very different road.

“I don’t know if I would have made the Hall of Fame,” Davis said in July 2011. “I had better years than some guys who are in. It’s not for me to judge.”

Herman Thomas Davis Jr. (“my dad was Herman, my mom always called me Tommy,” said Davis) was born March 21, 1939, in the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York. Tommy’s team was the Dodgers, more so than ever after Jackie Robinson joined the team in 1947. The Dodgers reached the World Series six times in the next nine years, each time facing the Yankees. Every time they played, the lone Yankee fan in Tommy’s family, his Uncle Dan, would make sure to stop by and rub it in – until 1955, when the Dodgers finally won it all. Uncle Dan conveniently left town. “Dan was 6’3”, about 250 and his voice carried through the block. I think he went to Jersey then. We caught up with him, though.”

By then, Davis was a 16-year-old sports star at Boys High. He and future NBA star Lenny Wilkens were All-City standouts on the basketball team. Tommy was the star catcher on the Boys baseball squad. Hitting came easily to him. He had begun his diamond career at the age of nine in fast-pitch softball. When Davis started playing hardball, he felt he had much more time to swing. He was never a pull hitter or a power hitter; from the earliest age he would simply take what pitchers gave him and hit the ball as hard as he could.

Davis learned the inside game of baseball from his coach on a Kiwanis League team, Clarence Irving. Irving was the only African-American manager in the league and he drilled the fundamentals into his players. The team was made up of all the different ethnic groups in Brooklyn’s melting pot. In 1955, Tommy’s team made it to the state championships against a team from Watertown. After Watertown built a 5–2 lead, their players began taunting Davis and his teammates with racial slurs. When he heard the word “Sambo,” he started tearing the cover off the ball. The boys from Brooklyn won 7–5.

Davis was on the radar of several teams, including the Phillies, Dodgers and Yankees. The Yankees rolled out the red carpet, telling Davis he could work out at the Stadium whenever he pleased. “I would hit with the pitchers and shag when the regulars hit,” Davis remembered. “I probably did that three or four times.” He was leaning towards signing with New York despite pleas from Dodger scout Al Campanis that he couldn’t forsake his native Brooklyn. Campanis also pointed out how the team’s black players enjoyed the atmosphere on the Dodgers.

A personal phone call from Jackie Robinson on the Sunday of the week Davis planned to sign sealed the deal. Davis signed with the Dodgers for $4,000 – the highest bonus a player could get without being compelled to spend two years in the majors. Another Brooklyn signee, Bob Aspromonte, also got $4,000 – plus some cash under the table. “I don’t remember what Jackie talked about. Probably the advantages of signing with the Dodgers,” Davis said. “The important thing was that he took the time to call. I was going to sign with the Yankees on a Tuesday night. Instead I signed with the Dodgers on a Tuesday afternoon.”

Davis spent his first summer as a pro with the Hornell Dodgers in upstate New York. It was the first time he played night baseball. It took some getting used to, but by the end of his first year he had hit .325 in 43 games. The 1957 season found Tommy Davis playing for Kokomo of the Class D Midwest League. He had been homesick the year before, but manager Pete Reiser took him under his wing and functioned as a father figure. He encouraged Tommy to be an aggressive hitter and base runner. He led the league that summer with a .356 average and set a league record with 68 stolen bases. Every time he took off, Reiser could only shake his head. Davis had no idea what he was doing, but against the easily flustered competition, he slid in safely time and again. “Pete Reiser made a man of me,” said Davis. “One time I was out late with a couple of teammates and when we got back to the rooming house we lived in, Reiser was in my bed. He looked at the three of us and said, ‘That will be 50-50-50 (in fines), and don’t wake me up.’ I had to sleep on the floor.”

Davis’s next stop was Victoria, Texas of the Texas League. He played 122 games for the Rosebuds in 1958 and batted .304 with an OPS above .800 against a much higher grade of competition – despite being the only teenager on the team, and despite an injured wrist. Tommy said he sometimes felt like Jackie Robinson playing in Texas. “There were a lot of racial problems in Victoria. The more they yelled, the harder I played.” Davis finished up the year with the Montreal Royals, the (now Los Angeles) Dodgers’ top farm club. He got into 14 games and batted .308. The Royals won the International League crown that fall.

Davis was basically a full-time outfielder at this point. That was where he played during his final stop in the minors, Spokane, the Dodgers’ Pacific Coast league affiliate. Playing 153 games for manager Bobby Bragan, Davis belted the ball at a .345 clip to win his second batting title. He learned a lot from his older teammates, including Bob Lillis, Frank Howard and Maury Wills. “That was the right place at the right time for me,” said Davis of his age-20 season. The Dodgers rewarded Davis with a September call-up. He came to the plate once in the final week and struck out against fellow rookie Marshall Bridges of the Cardinals. The Dodgers reached the World Series but Tommy was not eligible to play.

Davis made the Dodgers out of spring training in 1960. He earned his first career start, in center field, in the season’s third game, and collected his first major-league hit. It was an infield single off Ron Kline. Davis saw the most action of anyone in center field for the 1960 team, starting 57 games there. One foggy night, he made a Willie Mays-type over-the-shoulder grab in front of the Los Angeles Coliseum’s centerfield wall, 425 feet from home plate. It was a foggy night, so only the handful of fans sitting in the bleachers saw it. The umpire called the batter out based on their wild cheering after Tommy made the grab.

Davis made a respectable showing at the plate in his rookie season, batting .276 in 374 at bats. His 11 homers were fourth best on the club, as were his 44 RBIs. He lost several home runs to the net in left field – shots he claims would have gone out of any other ball park. Tommy drew only 13 walks, yet struck out a mere 35 times. In other words, he went up to the plate swinging. “My goal was to limit my strikeouts to one every ten at bats,” Davis said. “You don’t know what might happen any time you put the ball in play.”

Davis started in all three outfield positions again in 1961, but the position he played the most was third base. Walter Alston seemed determined to make Tommy into an infielder and worked him out there all spring. The experiment ended after the Dodgers acquired journeyman Daryl Spencer to play the hot corner. “They never really explained to me how you had to short-arm the ball at third,” Davis explained 50 years later. “I was throwing it like an outfielder and the ball was sailing over [Gil] Hodges’s head.”

Davis batted .278 with 15 homers, 58 RBIs, 10 steals and 60 runs scored in his sophomore campaign. He also received some much-deserved press. There were several “Boy from Brooklyn” type stories in newspapers and magazines, including a long feature in Sport. Baseball writers seemed to sense that he was on the verge of harnessing his talent, and wanted to get to know what kind of person he was. What they found was the opposite of a rah-rah guy, but not in a way that generated a negative portrayal. Davis was incredibly calm for a 23-year-old in one of baseball’s biggest pressure-cookers. And the quieter he was, the better he seemed to play – no matter where the Dodgers penciled him into the lineup.

None of the platitudes used to describe Tommy Davis, however, hinted at the offensive force he would become in his third major-league season. By early June, Davis’s average had climbed into the .330s. It never came down, as he piled up hits at a stunning rate. More impressive – and critical to the Dodgers’ success – was Tommy’s clutch hitting. He became an animal with men on base. He rarely went more than a couple of days without driving a runner in. The myth about the 1962 Dodgers is that the majority of their victories came by narrow scores. The truth is that either their offense clicked or it didn’t. When it did, they trounced opponents.

Of course, the headline-grabber for L.A. in 1962 was Maury Wills. When he reached base, he would either steal or Jim Gilliam and Willie Davis would try to move him into scoring position. Tommy spent most of the year hitting cleanup, so he often came to the plate with one or more speedy runners in scoring position. He had 100 RBIs before July was out – and started in both All-Star Games that month, too. “Every time Tommy came up with a man on second, he would drive him in with a single,” Sandy Koufax once recalled. “When he came up with a man on first, he drove him in with a double.”

“Starting and playing every day was the key,” said Davis, who played in 163 of the Dodgers’ 165 games that season. “Maury, Gilliam and Willie all had good years in front of me, and Frank Howard behind me hit 31 bombs (with 119 RBIs and a .906 OPS) so I saw a lot of fastballs. [Ron] Fairly was always pissed off. He said after Howard and I were done there was no one left for him to drive in.”

Early in the year, the Dodgers looked as if they might run away with the pennant. But they cooled off in the final two months. After losing 10 of their final 13, they found themselves in a first-place tie with the Giants. The ensuing playoff came down to a deciding third game. Davis drove a Juan Marichal pitch out of the park with a runner on in the sixth inning to give the Dodgers a 3–2 lead. L.A. tacked on a fourth run but could not hold the lead. Davis was on deck when the final out of the season was made.

Davis’s playoff homer gave him 27 for the season – the first and only time he would hit more than 20 in a year. His RBIs in the 165th game of the season (his 163rd) gave him 153 – a dozen more than Mays, who finished second. Tommy’s total was the highest for a National Leaguer since Ducky Medwick knocked in 154 in 1937. Davis had only 63 extra-base hits in 1962, which means a high number of his RBIs came on singles. This was a tribute in part to his clutch hitting, and to the Dodger offense, which was remarkably adept when it came to moving runners into scoring position. Davis’s .346 average was the best in baseball in 1962. Had Tommy gone hitless in the playoffs against San Francisco (instead of 3 for 11), he would have lost the batting title with a .341 average. Davis also led the league in hits with 230, the most in the senior circuit since Stan Musial produced the same number in 1948. Tommy was one off the lead league in triples, with nine, and was fifth in the NL with 120 runs scored. He stole 18 bases and, as a left fielder, was as good as there was in the league in 1962.

Tommy successfully defended his batting crown in 1963, finishing at .326, six points ahead of Roberto Clemente. The last Dodger to win consecutive batting titles was Jake Daubert, in 1913 and 1914. Davis led the team with 181 hits and 88 RBIs, and was second to Howard with 16 homers. After a slow start, the Dodgers caught fire and won the pennant with 99 victories. “We were a tight group that season. We had great speed and pitching. [Ron] Perranoski was outstanding, sometimes people forget that. And if I had to win one game [Johnny] Podres was right there with Koufax. Johnny would give you a short, efficient game. You could make early dinner reservations when Podres pitched,” said Davis.

The Dodgers swept the Yankees in the World Series. Davis tied a record with a pair of triples in Game Two. In Game Three he singled in the lone run in a 1-0 victory. He batted .400 to lead hitters on both clubs. The odds of sweeping the Yankees in the World Series were astronomical. Davis heard after the series that a gambler had put $1000 on a Dodger sweep in Las Vegas and won $100,000.

The 1964 season began with great promise for Tommy Davis and the Dodgers, but ended in disappointing fashion. L.A. won a meager 80 games, and Tommy’s average plummeted more than 50 points to .275. His power numbers were essentially the same, as were his RBIs. His WAR, however, dipped to 2.3 from 6.8 in 1962 and 4.6 in 1963. He was still a clutch hitter, relatively speaking, as he drove in 86 runs on 18 fewer hits. But coupled with truly disastrous seasons from Gilliam and Howard, the top of the Los Angeles lineup simply could not generate the runs needed to win tight ballgames.

The Dodgers recovered in 1965 to win 97 games and return to the World Series, but Tommy missed almost the entire season. On May 1, with the Giants in town, Davis was going from first to second on a grounder to Orlando Cepeda. Cepeda flipped to Gaylord Perry for the out at first. Tommy, not knowing whether there would be a play on him, made an awkward slide and snapped his ankle. “I was running on the inside of the baseline expecting Cepeda to throw to [José] Pagán,” Davis said slowly. “As I approached the bag I did a crossover step with my left leg and the back spike of my right leg caught in the clay and turned my foot completely around. Perry dove to tag me and I never felt it. I was in shock. Wayne Anderson (a Dodger trainer) came on the field and snapped my foot back in place right on the basepath.”

The leg was placed in a balloon cast in the clubhouse. “At that point I was feeling pretty good and was thinking maybe it’s not broken. Then Dr. (Robert) Kerlan came to see me, popped off the cast and said it felt like a bag of walnuts in my ankle. I said, ‘Oh man, don’t tell me that.’” He was done for the season with a break and a dislocation. The Dodgers caught a break when Tommy’s replacement, Lou Johnson, had a career year. His homer in Game Seven against the Twins was the decisive blow. “To this day when I see Lou he gives me a hug and thanks me for breaking my ankle and making his career,” Davis says now with a laugh.

Davis took the field in 1966 aiming to prove he could play at his previous high level. His batting stroke was still there, but the power was gone. He batted .313 to lead the club by 25 points, but had only 15 extra-base hits and only three home runs in 313 at bats. It was just enough to help the Dodgers repeat as pennant-winners, edging the Giants and Pirates on the final weekend. The Dodgers were solid favorites against the precocious Baltimore Orioles in the 1966 World Series. Incredibly, L.A. never led during the series, losing Game One 5–2 and getting shut out in the final three contests. Tommy started two games and appeared as a pinch-hitter in the other two.

After the season, the Dodgers traded Davis to the Mets for Ron Hunt and Jim Hickman. Tommy was asked to play left field and mentor New York’s young outfield corps, which included Ron Swoboda and Cleon Jones. Still a bit hobbled from his injury, Tommy nevertheless led the Mets in almost every offensive category in 1967. He had a team-best .302 average, 32 doubles, 16 home runs, 174 hits, 72 runs and 73 RBIs. Davis said that, including all his years with the Dodgers and later in Baltimore, that 1967 was his greatest year. “I had to prove myself again. By having a decent year I was able to play until 1976. I was certified good enough to play, thanks to 1967 with the Mets.”

The next stop for Davis was Chicago, where he joined a White Sox club that had just missed the pennant in 1967. The Mets received Tommie Agee and Al Weis in return. “I deserve some credit for that 1969 championship, don’t you think?” Davis joked. “You think the Mets would send me something for helping them win.”

Initially seen as the missing puzzle piece, Davis could not do much to prevent a total team collapse as Chicago dropped 95 games in 1968. To his credit, he hit .268 on a team that batted .228, and tied for the club lead with 50 RBIs. But he was basically a singles hitter, with only 16 of his 122 hits going for extra bases. After the season, the White Sox exposed Davis in the expansion draft and he was selected by the Seattle Pilots.

Tommy’s leg bothered him for much of the 1969 season, but like most of the Pilots, he was very active on the bases. He stole 19 in the five months he played in Seattle. He also clubbed 29 doubles, by far the most on the team. Davis was batting .271 and leading the Pilots in hits and RBIs when they traded him on August 30 to the Houston Astros. He played out the season for Houston, batting .241 and stealing one more base to make it an even (and career-high) 20. All told, he batted .266 with seven homers and 89 RBIs.

Davis had the distinction of being Jim Bouton’s teammate in both Seattle and Houston and as such was a featured player in Ball Four. While Davis said he didn’t like what Bouton wrote about Mickey Mantle, he and Bouton remain friends to this day. “He wrote nice about me,” Davis said. “He liked me. I’m not mad at him and I never was.” Davis also said that when he ran into Pilots manager Joe Schultz about a year after Ball Four came out, Schultz referred to Davis as “Bouton’s bo-bo.”

Davis spent 1970 with the Astros, A’s and Cubs. The call-up of teenage star César Cedeño in Houston made Tommy expendable. In Oakland, Davis was part of a formidable outfield that included Reggie Jackson, Rick Monday, Joe Rudi and Felipe Alou. Once the A’s had faded from contention, owner Charlie Finley agreed to sell Davis to the Cubs. Tommy’s totals for three teams in 1970 amounted to a .284 average with six homers, 65 RBIs and 10 stolen bases. The Cubs released him after the season; Tommy believed that Finley engineered that release from his Chicago insurance office in order to re-sign him at a bargain rate.

Davis remains a little bitter about this stage of his career. “Nobody gets released after hitting .284, you ever hear of that?” he asked. Since the Cubs released him, his next club was not bound by the 25% limit on salary cuts. Consequently, he says his salary went from about $80,000 to less than $40,000. “To lose that money that late in my career really hurt me. It affected my retirement payouts. I feel it to this day.” According to baseball-reference.com, Davis’s salary eventually dipped to $25,000 before recovering into the $30,000s with Baltimore in the middle 1970s.

Davis did indeed return to Oakland in 1971. He had a solid year and helped the club reach the playoffs for the time, but was released during spring training in 1972. This move was perceived by many as punishment because Tommy had introduced the team’s young star (and his Oakland apartment-mate) Vida Blue, to attorney Robert Gerst. With Gerst’s encouragement, Blue insisted on a new contract that did not include the dreaded reserve clause, leading to a memorable holdout in the midst of a historic players’ strike. No longer a viable everyday defensive player, Davis was out of baseball for several months before seeing part-time duty with the Cubs and Orioles in the second half of 1972.

Timing is everything in baseball. At 34, Davis could still hit, but his days as an everyday defensive player were at an end. The arrival of the designated hitter in 1973 season made him instantly relevant again. Serving as Baltimore’s fulltime DH, he led the team with 169 hits and 89 RBIs. His .306 average ranked third in the AL. Davis had another fine year in 1974, once again leading the Orioles in several key offensive categories, including hits (181), average (.289) and RBIs (84). Baltimore won the AL East, surviving a late charge by the Yankees. Alas, both years Baltimore’s season ended with an ALCS defeat at the hands of the Oakland A’s.

Davis’s final season as a major-league regular was 1975. Tommy’s .283 average was second on the club to Ken Singleton’s .300 mark. Davis was 36 at the end of the season but hardly fading. He had 25 hits in September to boost his average a dozen points. Even so, Baltimore’s DH job in 1976 was likely to go to slugger Lee May, who was becoming a defensive liability at first base. The Orioles released Tommy in February.

Davis caught on with the Yankees in 1976 but failed to make the team in spring training. He stayed in shape and signed to play with the Angels in June. He finished the year as the Royals’ DH, but joined Kansas City too late to be eligible for the epic ALCS showdown with the Yankees. KC’s designated hitters failed to bat their weight in that series. On October 2, Davis appeared in his 1,999th regular-season game. He collected a pair of singles—hits number 2,120 and 2,121.

When the Royals released Tommy Davis in January, he decided to call it quits. He was tired of moving from team to team, though he conceded that his lackadaisical approach may have irked some of his employers. Even in his glory years with the Orioles, he was known to disappear from the dugout between at bats to read or grab a shave. “The lazier I felt,” he liked to say, “the better I hit.” Besides, what manager would question a player who could come into a game cold and hit better? Besides his DHing prowess, Tommy retired with a lifetime .305 average as a pinch-hitter in 203 at-bats.

Davis stayed in baseball after retiring as a player. He worked for the Dodgers as a minor-league instructor and also as part of the community relations department. He and his wife, Carol, raised their daughter in Greater Los Angeles. Davis also has three daughters and a son from his first marriage. He served as the batting coach for the Seattle Mariners for one season in 1981 and eventually returned to the Dodgers – pressing the flesh out in the community and passing along batting tips to everyone from prospects to middle-aged fans at the team’s fantasy camps.

Davis remains in constant demand at autograph shows and as a speaker. In 2005, he co-authored Tommy Davis’s Tales from the Dodgers Dugout with Los Angeles Times sportswriter Paul Gutierrez. He also started a small company called Tommy Davis Enterprises that sells promotional items corporations use as giveaways.

Postscript

Davis died at the age of 83 on April 3, 2022, in Phoenix, Arizona.

Acknowledgments

Grateful acknowledgment to Tommy Davis for sharing his memories during telephone interviews on July 25 and August 17, 2011.

Sources

Periodicals

Los Angeles Times

New York Times

Baseball Digest

Ebony

Meet the Dodgers, Tommy Davis, 1961

Los Angeles Dodgers Yearbooks, 1959-1966

Sport

The Sporting News

Sports Illustrated

Books

Jim Bouton, Ball Four (20th Anniversary Edition). John Wiley & Sons: 1990

Mike Shatzkin (editor),The Ballplayers. Arbor House: 1990

Jeff Seidel, Baltimore Orioles: Where Have You Gone? Sports Publishing, LLC: 2006

Bill Libby, Ray Robinson (editor). Baseball Stars of 1964. Pyramid Books: 1964.

Larry Moffi & Jonathan Kronstadt, Crossing the Line: Black Major Leaguers 1947–1959. University of Nebraska Press: 2006

Robert L. Tiemann, Dodger Classics. Baseball Histories, Inc.: 1983

Bill James, The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract. The Free Press: 2001

Tommy Davis & Paul Gutierrez, Tales from the Dodgers Dugout. Sports Publishing, LLC: 2005

Full Name

Herman Thomas Davis

Born

March 21, 1939 at Brooklyn, NY (USA)

Died

April 3, 2022 at Phoenix, AZ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.