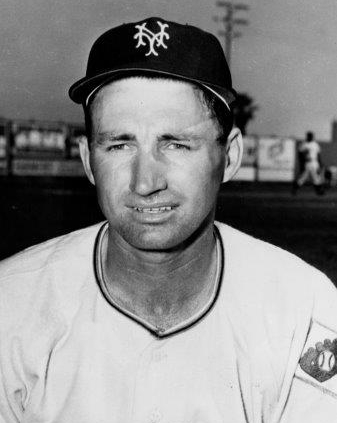

Alvin Dark

President John F. Kennedy was said to have correctly answered a trivia question that had been floating around for years: Who is the only man to ever hit a home run off Sandy Koufax and catch a pass from Y.A. Tittle? The guess was always Alvin Dark. “It’s not quite accurate, however,” Dark always said. “Tittle played at LSU after I did.”1

That JFK’s answer was presumed true said it all about Dark – a terrific three-sport athlete at Louisiana State University who in baseball excelled at each phase of the game. Joe DiMaggio called him the “Red Rolfe type of hitter,” meaning that he was ideal for the No. 2 spot, the type of batter who could “bunt or drag, hit behind the runner, or push the ball to the opposite field.”2

One of the best shortstops in Giants history, Dark played in 14 major-league seasons with the Boston Braves, New York Giants, St. Louis Cardinals, Chicago Cubs, and Philadelphia Phillies before returning to the Braves, then in Milwaukee, to finish his career. A three-time All-Star, he started at shortstop for the National League in the 1951 and ’54 contests. He was 24 years old when he broke into the big leagues with the Boston Braves on July 14, 1946, but was already nationally known for his collegiate exploits on the diamond and gridiron. A lifetime .289 hitter with 126 home runs and 757 RBIs, Dark, nicknamed the Swamp Fox, played on pennant winners with the 1948 Braves and ’51 Giants, and also helped win a World Series title for New York in 1954. He was the Rookie of the Year in 1948 and was captain of the strong Giants teams of the 1950s.

Dark also had a successful managing career. He won a pennant with the 1962 San Francisco Giants just after his playing days, a world championship with the Oakland A’s in 1974, and a division title for the A’s in 1975. Accordingly, he became the first man to manage All-Star teams for both leagues: the National League in 1963 and the American League in 1975. It was not quite a Hall of Fame career either on the field or in the dugout, but Dark was still one of the few men to reach the top of the heap in both roles.

Born on January 7, 1922, in Comanche, Oklahoma, Alvin Ralph Dark was the third of four children born to Ralph and Cordia Dark. Ralph was a drilling supervisor for the Magnolia Oil Company and a part-time barber. An amateur baseball star, he declined an opportunity to play in the Texas League to marry Cordia. Work brought the family, which also included son Lanier and daughters Margaret and Juanita, to Lake Charles, Louisiana.

Young Alvin battled malaria and diphtheria as a child, rendering him unable to attend school until he was 7. His athletic career blossomed at Lake Charles High School, where he made all-state and all-Southern football teams as a football tailback; and his skills as a basketball guard were superlative enough to earn him the team captaincy. Lake Charles High lacked a baseball team, and Alvin played American Legion ball.

Dark reconsidered a basketball scholarship from Texas A&M University to play football at Louisiana State in 1940. Playing halfback as a sophomore for the Tigers in 1942, he carried 60 times for 433 yards and a 7.2-yard rushing average. He also played basketball and baseball for LSU that year, lettering in all three sports.

With World War II raging, Dark in 1943 joined the Marine Corps’ V-12 program, which allowed him to continue his education for another year. The Marines sent him to the Southwestern Louisiana Institute in Lafayette, where he played for the greatest football team in the school’s history. Undefeated at 4-0-1 (most Southern schools did not play a full schedule during the war), SLI beat Arkansas A&M University 24-7 to capture the inaugural Oil Bowl. In that game, played in Houston, Dark ran for a touchdown, passed for another from his tailback slot, and kicked three extra points and a field goal.3

In addition to playing football in the 1943-44 school year, Dark was a member of SLI’s track, basketball, baseball, and even golf teams. His Marine V-12 obligations prevented him from playing the entire baseball season, but he made the most of his limited at-bats, going 12-for-26 (.462). After completing basic training at Parris Island and Camp Lejeune, Dark was commissioned at Quantico in January 1945 and was destined for service in the Pacific Theater. As he awaited orders at Pearl Harbor, he tried out for the Marine Corps baseball team, earning a berth on the lower-division squad.

In the end Dark never saw combat, but he still faced a pretty dicey situation. After the declaration of an Allied victory in the summer of 1945, he was sent to China that December to support the Nationalists against the Communists. He was dispatched to an outpost south of Peking (now Beijing) to guard the railroad and help transfer supplies to another station. Although his platoon did not know it, they had to pass through a Communist-controlled town to complete their mission. “Our group ran the supply line for four months before being relieved,” said Dark. “A month after I got back to the United States, I received word that the Marines who took our place were ambushed in the Communist town and massacred.”4

When he returned home to Lake Charles, Dark learned that he had been drafted to play pro football for the NFL’s Philadelphia Eagles. His first love was baseball, however, and Ted McGrew, a scout for the Boston Braves, had been watching Dark play in college. McGrew, who had helped engineer the trade of Pee Wee Reese from the Red Sox to the Dodgers, admired young Dark for his tenacity and competitive spirit in all sports. Spurning reported interest from several clubs, Dark signed with the Braves for $50,000: a $45,000 bonus and $5,000 to complete the season with Boston. The date was July 4, 1946.

Dark’s obligations to the Marines prevented him from joining the Braves until July 14. That day, in the second game of a doubleheader against the Pittsburgh Pirates at Forbes Field, he pinch-ran for catcher Don Padgett in the ninth inning of a 5-2 loss. A month later, on August 8, Dark got his first hit, a double off Phillies’ pitcher Lefty Hoerst at Philadelphia. Once again the Braves were defeated, as the Phillies triumphed, 9-8.

Dark played 15 games for the fourth-place Braves in 1946. Although he had just three hits in 13 at-bats, all were doubles – a nice harbinger of things to come (he wound up hitting 358 big league two-baggers). At spring training in 1947, Dark pleaded with manager Billy Southworth to retain him as a regular player. Southworth preferred to keep veteran Sibby Sisti as his starting shortstop, however, and optioned Dark to Milwaukee.

That summer, his only season in the minors, Dark hit .303 with 10 home runs, 7 triples, 49 doubles, 186 hits, and 66 RBIs. He earned American Association honors as All-Star shortstop and Rookie of the Year, and finished third in the Most Valuable Player balloting. Playing for manager Nick Cullop, Dark led the league in at-bats, runs, putouts, assists, and, dubiously, errors. His fielding, however, was considered solid; while not the flashiest of shortstops, he had good range and would become a good double-play man.

After the 1947 season Dark returned to Southwest Louisiana Institute to complete his degree in physical education. Although he wanted to compete in collegiate athletics, his request was denied because he had signed a professional contract. He did, however, serve briefly as the football coach’s athletic assistant.

Dark made the Opening Day varsity for the Braves in 1948, but was relegated to the bench as veteran Sisti continued as the regular shortstop. Nevertheless, Dark persevered. His contributions as a reserve player eventually won him the starting job, and he wound up fourth in the National League in batting with a .322 average. He contributed 3 home runs, 39 doubles (third in the NL), and 48 RBIs from his No. 2 spot in the order, while fielding his position strongly (a .963 fielding mark, well above the league average). Initially, his tenure in 1946 disqualified him from the Rookie of the Year ballot. However, the Baseball Writers Association of America ruled that year that players with 25 games or less in previous seasons would qualify for the ballot. This allowed Dark to win Rookie of the Year honors for 1948, the last season both leagues combined to acknowledge one freshman player. He also finished third in the vote for NL Most Valuable Player, but was a letdown in his first World Series by batting just .167 with one double in 24 at-bats. The Braves lost to the Cleveland Indians in six games.

Dark’s outstanding rookie campaign was augmented by the exploits of his keystone partner, second baseman Eddie Stanky. Known as “The Brat,” Stanky had been traded to the Braves by the Dodgers during spring training. Not only were Dark and Stanky a great double-play combination for years to come, but they became close friends and roommates. Dark considered Stanky and Danny Murtaugh as his greatest mentors; as Dark remarked in his autobiography, “Stanky knew so much more about the game than anybody else. If there were ten possible percentage plays to make, most guys would know four or five. Stanky would know ten.”5

Their strong double-play duo notwithstanding, the Braves had a disappointing 1949. They fell to 75 wins against 79 losses, good for just fourth place. Dark’s batting average fell as well – to .276.

Just behind the Braves in the 1949 standings were the New York Giants, who finished a pedestrian fifth place at 73-81. New York manager Leo Durocher and team president Horace Stoneham attributed the shortcoming to inadequate speed and defense. To improve in these areas, the Giants traded outfielders Willard Marshall and Sid Gordon, shortstop Buddy Kerr, and pitcher Sam Webb to the Braves on December 14 for Dark and Stanky. The blockbuster deal was panned in Gotham, as the trade cost the Giants power hitters Marshall and Gordon – the latter a particularly strong fan favorite as one of the league’s foremost Jewish sluggers. Fans at the Polo Grounds were also initially lukewarm to accepting Stanky, as he had previously played for the archrival Dodgers.

Dark, however, came with no such baggage, and Durocher immediately took to his new shortstop. As Dark later wrote, “Leo stuck by me in the early part of 1950, when I first came to the Giants and couldn’t seem to get started … yet Durocher stood by and kept telling me not to worry, that I would seem to come out of it.”6

Durocher surprised Dark once again that first season by declaring the shortstop his team captain. Most sportswriters assumed that Stanky, not Dark, would get the nod. After all, it was the extroverted Stanky who emulated Durocher, in speaking his mind to the press and in the clubhouse. Yet Leo chose Dark, speculating that the position could easily build confidence in the mild-mannered infielder and help him emerge as a team leader.

“In my first year [as captain], all I did was take the lineup to home plate. After the success we had in 1951, I began taking on some responsibilities – automatic things, like consoling a guy after a bad day. After a while some of the younger players came around, and some of them, like (Willie) Mays, still call me ‘Cap.’”7

In 1950 the Giants improved to third place with a record of 86-68. Playing in all 154 games, Dark batted .279 with 16 homers and 67 RBIs – by far his best power numbers to that point. It was in that season that the Giants made history.

Early in the campaign, the Giants promoted rookie outfielder Willie Mays from Minneapolis, and he was soon dazzling the league with his graceful catches and power. The Giants also boasted clutch-hitting outfielder Monte Irvin, who had 121 RBIs that year, 32-homer man Bobby Thomson in the third outfield slot, and pitchers Sal Maglie and Larry Jansen, each a 23-game winner. Dark, for his part, had a terrific year, hitting .303 with a career-high 196 hits, a league-best 41 doubles, 114 runs scored, and 14 homers. Defensively he led the league with 45 errors at shortstop, but he also was tops in assists (465) and double plays (114) in making his first All-Star team. Still, the Giants trailed the Dodgers by 13½ games as late as August 11. How was anyone to guess that they were about to complete one of the greatest pennant races in baseball history? The Giants won 37 of their last 44 games to tie the Dodgers at the end of the season and force a best-of-three playoff.

In the third game, with the teams tied, 1-1, Brooklyn had a 4-1 lead going into the bottom of the ninth at the Polo Grounds. With Dodgers ace Don Newcombe on the mound, Dark led off the inning with a single off the glove of first baseman Gil Hodges. “I must have fouled off six or seven pitches with two strikes before getting that hit,” Dark recalled.8 Four batters later, after Dark had scored, Bobby Thomson hit his legendary three-run homer to cap the “Miracle at Coogan’s Bluff” and win the pennant, 5-4. Dark hit .417 with three doubles, a home run, and four RBIs in the World Series that followed, but the Yankees reigned supreme, winning in six games.

After the 1951 season, Dark’s friend and teammate Eddie Stanky was traded to the St. Louis Cardinals. Without this sparkplug, and with Willie Mays in the Army most of the year, the Giants finished 1952 in second place, 4½ games behind the Dodgers. Meanwhile, Durocher had become impressed with farmhand Daryl Spencer, who dazzled at shortstop while playing for Minneapolis. Durocher wanted to play Spencer at shortstop and move Dark to second or third base. Dark expressed his displeasure by intruding on a press conference orchestrated by Durocher. Things smoothed over, however, and Spencer departed for military service after the 1953 season. After his greatest season at the plate, in 1953, batting .300 with 23 home runs and 88 RBIs, Dark emerged as the undisputed shortstop for the New York Giants.

Perhaps the resolution of this conflict helped the club. After a disastrous 1953 season in which the Giants finished fifth, the team went on a roll the next spring. The press began referring to the squad as “Happy Heroes, Inc.,” because they would always find a way to beat you, whether it was a pinch-hit home run or solid pitching.9 Dark was reunited with erstwhile Braves teammate Johnny Antonelli, and the starting pitcher won 21 games after the Giants acquired him in a trade for Bobby Thomson. Center fielder Mays returned from the Army and emerged as a superstar, leading the National League with a .345 average while slugging 41 home runs and driving in 110 runs. The Giants finished five games ahead of the Dodgers, winning the pennant with a record of 97-57.

This time the Giants faced the Cleveland Indians, winners of 111 games, in the World Series. After hitting a solid .293 with 20 home runs and 70 RBIs during the year, Dark had another outstanding postseason with a .412 batting average on seven hits and a walk in 18 plate appearances. Boosted by his output and the incredible pinch-hitting of Dusty Rhodes (two homers, seven RBIs), the Giants surprised by sweeping the Indians. While Mays was the runaway choice as league MVP, Dark finished fifth in the balloting and even got one first-place vote.

An injury-plagued 1955 campaign was Dark’s last full season as a Giant. After fracturing his rib in a game against Cincinnati on August 7, he separated his right shoulder against the Phillies on September 2. Dark’s injuries limited him to 115 games, and he ended the year hitting .282 with 9 homers and 45 RBIs. New York finished 18½ games behind the Dodgers, in third place.

The 1956 season started off dismally for the club, and by early June the Giants were settled into seventh place with a record well under .500. A shakeup was in order, and in an eight-player deal on June 14 the Giants sent Dark, Ray Katt, Don Liddle, and Whitey Lockman to the St. Louis Cardinals for Dick Littlefield, Jackie Brandt, Red Schoendienst, and Bill Sarni. New York wanted a second baseman (Schoendienst), and the Cardinals wanted a shortstop (Dark). It was initially a good move for Dark; the 1957 season, his last as a regular shortstop, was also his final pennant race as a player. He hit .290 as the Cardinals finished in second place, eight games behind the Milwaukee Braves.

Dark now became a third baseman – and a “traveling man.” On May 20, 1958, the Cardinals traded him to the Chicago Cubs for pitcher Jim Brosnan; in his two seasons in Chicago, he hit .295 and .264 while playing alongside another standout shortstop, Ernie Banks. On January 11, 1960, Dark was swapped again, along with pitcher John Buzhardt and infielder Jim Woods, to the dismal Philadelphia Phillies for outfielder Richie Ashburn. Dark’s first hit of the season in Philadelphia’s home opener against the Braves on April 14, 1960, was the 2,000th of his major-league career. He played 53 games at third base (hitting .242) before a June 23 trade for infielder Joe Morgan (later the Boston Red Sox manager) sent him to the Milwaukee Braves. Now 38, he was used primarily as a utility infielder, pinch-hitter, and occasional outfielder. Appearing in 50 games for the second-place Braves, Dark upped his productivity, batting .298 with one homer and 18 RBIs.

Still, it wasn’t long before Dark was sent packing again. On October 31, 1960, he was traded for the sixth and last time when the Braves dealt him to the San Francisco Giants for infielder André Rodgers. With his future uncertain, Dark accepted a sales position with the Magabar Mud Company in Louisiana. He did not peddle mud for long, however, as he was named to replace Tom Sheehan as the Giants manager for 1961.

In his first press conference as skipper, Dark was asked if he retained any memento from the 1951 Miracle at Coogan’s Bluff. “Yeah,” the manager replied humorously. “Willie Mays!”10 He demonstrated very quickly his ability and fortitude to make bold moves with his roster and in game situations, thereby emulating his mentor Leo Durocher. He intended to eliminate any racial cliques by reassigning clubhouse lockers that integrated whites with blacks. “We’re all together and fighting for the same cause. This way we’ll all get to know each other better,” he said. 11 Dark also moved the Giants’ bullpen across the field to better monitor pitchers who might not be focused on the game.

Although Dark earned a reputation for avoiding controversy as a player, he embraced it as a manager. Despite his strong religious views as a Baptist fundamentalist, he was prone to temper tantrums. To ventilate his anger after a 1-0 loss to Philadelphia on June 26, 1961, for instance, he flung a metal stool against the wall. In the process, he lost the tip of his little finger, requiring hospitalization for its repair. “I made up my mind two weeks ago not to take my anger out on the players. So, I guess I took it out on myself tonight,” he said in jest. 12

In his first season as manager, Dark guided the Giants to a third-place finish at 85-69, eight games behind pennant-winning Cincinnati. The next season, 1962, he led the Giants to a sparkling 103-62 record and their first National League championship in San Francisco. Mays, Felipe Alou, Orlando Cepeda, and Willie McCovey combined to hit 129 homers, and Jack Sanford led the pitching rotation with 24 wins.

The Giants’ 1962 campaign was not without its controversy. Even as West Coast transplants, they retained their rivalry with the Los Angeles Dodgers. LA shortstop Maury Wills was en route to a then-record 104 stolen bases, and according to the Dodgers, the Giants were trying to slow him down. At one point during a three-game series at San Francisco’s Candlestick Park in August, the infield was soaking wet around first base. The umpires had no choice but to douse the wet surface with sand, thereby preventing baserunners from stealing. For his alleged role in the situation, Dark earned the nickname “Swamp Fox.” Dark responded to the incident with a “Who, me?” attitude. As he remarked to Baseball Digest some 40 years later, “I just remember that one day they had trouble with a hose that broke.”13

Just as in 1951, the ’62 NL pennant race came down to a tie finish and a three-game playoff with the Dodgers to decide a champion. The Giants triumphed again, and in another ’51 rematch, they faced the Yankees in the World Series. Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris, sparked the Yankees’ offense, complementing a rotation led by Whitey Ford and Ralph Terry. San Francisco took New York to the limit, but fell 1-0 in Game Seven at Candlestick Park. After this near-miss, the Giants returned to third place under Dark in 1963, posting an 88-74 record to finish 11 games behind Los Angeles.

Dark has been linked to a great urban legend involving Gaylord Perry, who pitched for the Giants’ teams from 1962 to 1964 and was a notoriously weak hitter (.131 career batting average). Dark was said to respond to sportswriter Harry Jupiter’s comments on Perry showing some pop in batting practice by saying, “There would be a man on the moon before Gaylord Perry would hit a home run.” Sure enough, on July 20, 1969, Perry hit a home run in the third inning off Dodgers pitcher Claude Osteen. How long the home run came after Neil Armstrong stepped onto the lunar surface when the home run came is debatable. In any event, Perry hit five more homers before retiring.14

On June 7, 1964, during the last of a three-game series with the Phillies at Connie Mack Stadium Dark exemplified why the Bay Area had dubbed him the “Mad Genius” when he used four pitchers in the first inning. 15 He sent starter Bob Henley to the showers for surrendering two runs without retiring a batter, and when reliever Bob Bolin walked one man, he, too, was replaced, by Ken MacKenzie. MacKenzie retired a pinch-hitter before Gaylord Perry was summoned to record the final two outs of the frame. The craziness worked; 10 innings later, the Giants beat the Phillies 4-3.

Dark’s Giants completed the 1964 season with a fine 90-72 record and a fourth-place finish. However, his role at the center of a controversial article numbered his days in San Francisco. Midway through the season, Stan Isaacs of Long Island Newsday asked Dark about the Giants’ performance. The manager responded by accusing his players of making recent “dumb” plays.16 Although he later insisted that his comments were specific to baserunning mistakes by Orlando Cepeda and Jesús Alou, it was already too late; because his team was made up primarily of African-American, Puerto Rican, and Dominican players, Dark was unfairly painted as a racist.

On August 4, 1964, Dark called a press conference at Shea Stadium in New York to explain that the newspapers had misinterpreted him, but it mattered not; Horace Stoneham fired him at the end of the season. Several high-ranking baseball officials declared their support for Dark, including Commissioner Ford Frick. Perhaps most significantly, former Dodgers great Jackie Robinson quickly rushed to Dark’s defense. The two had been friends since their playing days, and Robinson told the New York Times that he had “known Dark for many years, and my relationships with him have always been exceptional. I have found him to be a gentleman, and above all, unbiased. Our relationship has not only been on the baseball field but off it. We played golf together.”17

Surely boosted by this vote of confidence, Dark moved beyond the Giants and was subsequently hired as the third-base coach for the Chicago Cubs. Then, at the end of the 1965 season, Charlie Finley hired him to manage the Kansas City Athletics. Dark was already the sixth manager hired by the maverick Finley in the six years he had owned the team. The A’s boasted an unknown young club with Catfish Hunter, Blue Moon Odom, and Lew Krausse in the starting rotation. After losing 103 games in 1965, the A’s went 74-86 in 1966 during Dark’s first season as skipper.

Despite considerable talent, lackluster baseball and personality issues caused the A’s to fall back into the cellar in 1967. After an incident that alleged player rowdiness on an airline flight, Dark had the distinction of being fired, rehired, and fired again on August 20. Not even Hall of Famer Luke Appling could resurrect the A’s as Dark’s replacement. With two All-Star shortstops at the helm, the A’s finished with a record of 62-99.

After the 1967 season, the Cleveland Indians hired Dark as manager and general manager. He led the team to its best record in nine years in 1968, with 86 wins and 75 losses. But in 1969 the Indians finished last, at 62-99. Without a substantial budget, they improved a bit in 1970 but returned to last place in 1971. With the team’s record 42-61 on July 30, 1971, Dark was fired as manager and general manager, completing his four years at the Cleveland helm with a lackluster .453 winning percentage (in San Francisco, he had won at a .569 clip).

For the next two years, Dark lived in Miami, where he excelled as a regular golfer by winning local tournaments. He supplemented his savings as an after-dinner speaker at churches, lecturing on baseball and the Bible. By 1974, however, Dark missed managing. As spring training dawned on February 20, he accepted old pal Charlie Finley’s offer to return to the A’s, by now in Oakland, as their skipper.

Dark faced enormous pressure assuming the reins of baseball’s most combative and successful team. Under Dick Williams the A’s had won the World Series in 1972 and 1973. Although one year remained on Williams’s contract, differences with Finley led him to resign. Dark accepted a one-year, $50,000 contract as Williams’s successor, with incentive bonuses if he won the pennant or World Series. An Oakland reporter heralded Dark’s arrival by writing, “The only thing worse than being hired by Charlie Finley [is] being hired by him a second time.”18

Dark claimed that his renewed religious faith had made him a changed man. No longer would he berate his players or belittle them publicly. He vowed to accept Finley’s suggestions, avoiding a renewal of their feud. Certain players, like Reggie Jackson, accepted Dark’s new personality, while others, such as Vida Blue, were rather critical. A fellow Louisianan, Blue “knew Alvin Dark was a religious man, but he’s worshipping the wrong god – Charles O. Finley.”19

The Oakland team Dark managed in 1974 had few weak spots. Catfish Hunter posted a record of 25-12, led the league with a 2.49 ERA, and won the Cy Young Award. Powered by a lineup featuring the likes of Jackson, Sal Bando, and Joe Rudi, the club captured its fourth consecutive division title by five games over the Texas Rangers. The A’s pitchers proved dominant over the Baltimore Orioles in the League Championship Series, at one point tossing 30 consecutive scoreless innings. Oakland won the series, three games to one.

The 1974 World Series was the first to feature only California teams: the A’s and manager Walter Alston’s Dodgers. After defeating Los Angeles in five games for his first Series title as a skipper, Dark agreed to return to Oakland in 1975. And despite losing Hunter as a free agent, he guided the A’s to yet another divisional title. With a record of 98-64, the A’s paced the division with a comfortable seven-game lead over the Kansas City Royals, but the 1975 Red Sox swept Oakland in three games in the playoffs.

On October 17, 1975, Charlie Finley announced that Dark’s contract would not be renewed. Dark returned to the Cubs as a coach for manager Herman Franks in 1977 before replacing John McNamara as the San Diego Padres’ manager on May 28. Although the Padres played well under Dark, their second-half record could not lift them beyond a final mark of 69-93. Citing a “communication problem,” Padres general manager Bob Fontaine fired Dark on March 21, 1978.20 He was only the second manager in major-league history to be released during spring training.

Dark was inducted into the Oklahoma Sports Hall of Fame, the Louisiana Sports Hall of Fame, the Louisiana State University Sports Hall of Fame, and the New York Giants Baseball Hall of Fame. Dark married his childhood sweetheart, Adrienne Managan, in 1946, and the couple had four children, Allison, Gene, Eve, and Margaret. They divorced in 1969, and Dark was remarried a year later, to Jackie Rockwood, and adopted her children, Lori and Rusty. He returned to baseball as the farm-system evaluator for the Cubs in 1981, and in 1986 was hired as director of minor leagues and player development for the Chicago White Sox.

Dark was 92 years old in 2014, with 20 grandchildren and three great-grandchildren. He moved from San Diego to Easley, South Carolina, in 1983. He became involved with the Alvin Dark Foundation, which financially supports ministries,

As of January 2014, Dark was the oldest living manager of a World Series-winning, pennant-winning or postseason team.

On November 13, 2014, Dark died at home in Easley, South Carolina.

This biography has appeared in “The Team That Time Won’t Forget: The 1951 New York Giants” (SABR, 2015), edited by Bill Nowlin and C. Paul Rogers III; “Mustaches and Mayhem: Charlie O’s Three Time Champions: The Oakland Athletics: 1972-74” (SABR, 2015), edited by Chip Greene; and “Spahn, Sain, and Teddy Ballgame: Boston’s (almost) Perfect Baseball Summer of 1948” (Rounder Books, 2008), edited by Bill Nowlin.

Sources

Dark, Alvin, and John Underwood, When in Doubt, Fire the Manager. (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1980).

Markusen, Bruce, A Baseball Dynasty: Charlie Finley’s Swingin’ A’s. (Haworth, New Jersey: Saint Johann Press, 2002).

Meany, Tom, The Incredible Giants. (New York: A.S. Barnes, 1955).

Stein, Fred, and Nick Peters, Giants Diary: A Century of Giants Baseball in New York and San Francisco (Berkeley: North Atlantic Books, 1987).

Boyle, Robert, “Time of Trial for Dark,” Sports Illustrated, July 6, 1964, 26-31.

Bush, David, “Turn Back the Clock 1962: When the Giants Lost a Heartbreaker to the Yankees,” Baseball Digest. October 2002.

Dark, Alvin, and John Underwood, “Rhubarbs, Hassles, Other Hazards,” Sports Illustrated, May 13, 1974, 42-48.

McDonald, Jack, “Alvin Assigns New Lockers in Effort to Kill Cliques,” The Sporting News, April 19, 1961, 26.

Stevens, Bob, “Dark Blows Stack – Loses Finger-Tip on Metal Stool,” The Sporting News, July 5, 1961, 9.

Tourangeau, Dixie, “Spahn, Sain, and the ’48 Braves,” The National Pastime (SABR), 1998, 17-20.

“Dark’s First Hit of the Season No. 2,000 for His Career,” The Sporting News, April 27, 1960, 8.

Newell, Sean, “Did Neil Armstrong Help Perry Get His First Home Run?,” Deadspin.com, August 12, 2010 (deadspin.com/5937875/did-neil-armstrong-help-gaylord-perry-get-his-first-career-home-run.)

Louisiana’s Ragin’ Cajuns Athletic Network, athleticnetwork.net

Notes

1 Alvin Dark and John Underwood, When in Doubt, Fire the Manager (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1980), 32.

2 Tom Meany, The Incredible Giants, (New York: A.S. Barnes, 1955), 73.

3 Louisiana’s Ragin’ Cajuns Athletic Network (athleticnetwork.net).

4 Dark and Underwood, 36.

5 Dark and Underwood, 42.

6 Meany, 74.

7 Dark and Underwood, 59.

8 Interview with Alvin Dark, December 18, 2006.

9 Meany, The Incredible Giants, 76.

10 Fred Stein and Nick Peters, Giants Diary: A Century of Giants Baseball in New York and San Francisco, (Berkeley: North Atlantic Books, 1987).

11 Jack McDonald, “Alvin Assigns New Lockers in Effort to Kill Cliques,” The Sporting News, April 19, 1961, 26.

12 Bob Stevens, “Dark Blows Stack – Loses Finger-Tip on Metal Stool,” The Sporting News, July 5, 1961, 9.

13 David Bush, “Turn Back the Clock 1962: When the Giants Lost a Heartbreaker to the Yankees,” Baseball Digest, October 2002.

14 There was a dispute over whether the words came from Dark or Perry, but the late umpire Ron Luciano said they were uttered by Dark. Ron Luciano with David Fisher, Strike Two (New York: Bantam Books, 1985). The controversy was also addressed by Sean Newell on Deadspin on August 25, 2012: (Sean Newell, “Did Neil Armstrong Help Perry Get His First Home Run?,” Deadspin.com, August 12, 2010 (deadspin.com/5937875/did-neil-armstrong-help-gaylord-perry-get-his-first-career-home-run.)

15 Robert Boyle, “Time of Trial for Dark,” Sports Illustrated, July 6, 1964, 28.

16 Alvin Dark and John Underwood, “Rhubarbs, Hassles, Other Hazards,” Sports Illustrated, May 13, 1974, 48.

17 Dark and Underwood, When in Doubt, 98.

18 Dark and Underwood, When in Doubt, 166.

19 Bruce Markusen, A Baseball Dynasty: Charlie Finley’s Swingin’ A’s, (Haworth, New Jersey: Saint Johann Press, 2002), 289.

20 Dark and Underwood, When in Doubt, 230.

Full Name

Alvin Ralph Dark

Born

January 7, 1922 at Comanche, OK (USA)

Died

November 13, 2014 at Easley, SC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.