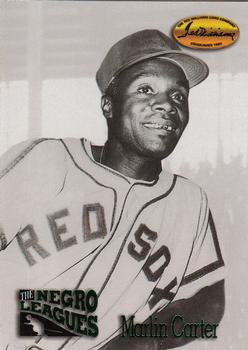

Marlin Carter

Despite missing two of his prime seasons while serving his country during World War II, Marlin Carter played professional baseball for nearly a quarter-century in major and minor Negro Leagues. Nicknamed “Pee Wee,” the 5-foot-7, 160-pounder threw right-handed and batted lefty. Primarily a third baseman, he also saw action at second base and shortstop, and often hit leadoff. Carter enjoyed his greatest success with the Memphis Red Sox and helped that club win its only Negro American League pennant in 1938.1

Despite missing two of his prime seasons while serving his country during World War II, Marlin Carter played professional baseball for nearly a quarter-century in major and minor Negro Leagues. Nicknamed “Pee Wee,” the 5-foot-7, 160-pounder threw right-handed and batted lefty. Primarily a third baseman, he also saw action at second base and shortstop, and often hit leadoff. Carter enjoyed his greatest success with the Memphis Red Sox and helped that club win its only Negro American League pennant in 1938.1

Marlin Theodore Carter was born on December 27, 1912, in Haslam, Texas, near the state’s eastern border with Louisiana.2 The town was named for Will Haslam, general manager of the W.R. Pickering Lumber Company. The Pickering mill opened shortly before Carter’s first birthday with a racially diverse workforce.3 Within two weeks, threats against the African Americans dwelling in the town’s segregated housing caused many of them to leave and – according to one report – cross the Sabine River and buy all the guns and ammunition in nearby Logansport, Louisiana to defend themselves.4

Carter was the youngest of Henry and Missouri (Jefferson) Carter’s three children, following son T.C. (Talmadge) and daughter Addie. He attended Haslam Elementary school for six years.5 He explained, “My father was a carpenter, and he moved the family to Shreveport [Louisiana), where he could find work. … But I spent a lot of time in East Texas. And, since I was born there, I’m a Texan.”6

In Shreveport, Carter played high school baseball and football at Louisiana Collegiate Institute (LCI). “T.C. started playing ball with the [semipro] Little Rock Stars,” he said. “I guess I wanted to follow my older brother, so I was hoping to make it as a ballplayer too.” One of LCI’s rivals was Central High School, whose team featured future Hall of Famer Willard Brown. “We played against each other and got to be friends,” Carter recalled.7

In 1926, T.C. joined the Shreveport Black Sports of the Texas Colored League and arranged a tryout for his brother. “Willard and I, and a couple other Shreveport boys, like Barney Morris went together,” Carter explained.8 The two Carters made the team, along with Brown, but the minor Negro League folded after the season.

Carter spent the next five years with the San Antonio Black Indians, initially under the management of Ruben Jones, whom he recalled as good, fair man. “The team had a lot of older players who saw any young player as a threat – a threat to their jobs,” he said.9 From 1929-1931, the Black Indians were part of the Texas-Louisiana League, a new minor Negro League.10 Many of their games were played in ballparks belonging to clubs in the Class A Texas League, an all-white loop. Although Carter spent five years with the Black Indians, he called the 1931 season his first as a professional ballplayer. After it concluded, he played in Mexico City.11

According to the census, Carter’s family was back in Haslam by 1930, with his mother widowed, and T.C. married and hauling logs to pay bills. As for Marlin’s salary with the Black Indians, he said, “There was never a lot of money, and getting your share of it wasn’t easy.”12

In 1932, Carter joined the Monroe (Louisiana) Monarchs of the Negro Southern League (NSL). Team owner Fred Stovall had erected a ballpark, a recreation center for his players, and a casino on his plantation. The Monarchs traveled in three brand-new Ford automobiles. “I always got paid!” Carter said. “That was the main thing when you played Black baseball back then – were you going to get paid?”13 On Good Friday, the Pittsburgh Crawfords – the strongest Black team in the country – visited Monroe for an exhibition and pitched their ace, Satchel Paige. Carter didn’t start that day, but he pinch-hit for shortstop Leroy Morney and struck out against the future Hall of Famer. They faced off again that spring and Carter recalled, “I hit a bullet right back at the mound. Satchel had to dodge, and the ball went right through for a hit…It was one of the best moments of my career.”14

In retrospect, the NSL is considered the only major Negro League of 1932.15 It was the only one to complete its schedule during a year marred by the Great Depression. Carter appeared in just two of the Monarchs’ 52 official contests, spelling second baseman Augustus Saunders and going 2-for-6.

In 1933, the reformed Negro National League (NNL) became the leading Black circuit, and the NSL was deemed a minor league. Carter, 20, remained in the NSL, but with a new team – the Memphis (Tennessee) Red Sox. “Memphis was a good place to play, and it was a pretty good place to live,” he said. “All the northern players wanted to come to Memphis to mess around Beale Street!”16 Carter usually played third base and batted third in the lineup. On July 13, 1933, he helped the Red Sox split a doubleheader with the NNL’s Nashville Elite Giants. With daylight running out in the second contest, neither team hit safely until Carter beat out an infield single against Percy Bailey to begin the bottom of the sixth. After moving to third on a double, Carter scored the decisive run on a bunt by Memphis’s Bill Harvey – the winning pitcher with a six-inning no-hitter.17 In NSL competition, Memphis posted a league-best 32-10 first-half record, though second-half statistics are unavailable.18 In August, the Red Sox took off on a barnstorming tour of the Midwest and won 12 of their first 15 contests.19

Memphis followed a similar barnstorming blueprint following league play in 1934. After Carter doubled, tripled, and scored twice in a 9-6 victory over a club in Lincoln, Nebraska on July 9, a newspaper proclaimed the Red Sox the “fastest colored team in the south.”20 In September, the Red Sox traveled to Council Bluffs, Iowa and won the Class A title in that state’s southwestern tournament.21

Carter was recruited to join the Cincinnati Tigers in 1935.22 The Tigers had been organized the previous year by DeHart Hubbard, the first African American to win an Olympic gold medal.23 The team was funded by Henry Ferguson, publisher of Cincinnati’s African American newspaper, the Mirror. 24 For Carter’s first two years, the Tigers were an independent group of paid barnstormers. During a visit to Renfrew Park in Edmonton, Canada on August 28, 1935, Carter’s performance batting leadoff in a 7-1 victory over the Shasta Royals made quite an impression. “Outstanding star of the struggle was Carter, shortstop of the visitors, who hammered out a home run, a three-bagger and two singles in five times at bat,” the Edmonton Bulletin reported. He also stole one base and participated in three double plays – one unassisted.25 Cincinnati’s winning pitcher was submariner Porter Moss. “When other teams came to town, Porter would go over to their hotel and tell them what he was gonna do to them the next day when he was pitching,” Carter recalled. “They say it ain’t bragging if you can do it. Well, he wasn’t bragging.”26

When Major League Baseball retroactively conferred Major League status on certain Negro Leagues in 2020, 12 of the 1936 Cincinnati Tigers games qualified. They went 2-10, but Carter scored 14 runs and batted .375 with four triples in the 11 contests for which box scores were found.

In 1937, the Tigers joined the nascent Negro American League (NAL) with Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe serving as the team’s playing manager. “Marlin was a good player who could hit, and he was fast,” Radcliffe recalled in 1993. “I managed him for eight years – he wouldn’t have been with me that long if he wasn’t a good player. He was a clean player, a true gentleman if there ever was one.”27 The Cincinnati Tigers played their home games at Crosley Field and, according to an MLB.com retrospective, they often outdrew the major-league Reds.28 Yet, the Tigers folded at the end of the season. Carter appeared in 37 games for which records are available and hit .233 as the regular third baseman.

Many of Cincinnati’s core players moved on to the NAL’s Memphis Red Sox in 1938. Carter prepared to head to Memphis as well, but he couldn’t agree to contract terms. At the request of his former San Antonio skipper, Ruben Jones, he joined the Mineola-based Texas Black Spiders barnstorming squad. “I stayed there just a few weeks,” he recalled. “But I had a good time.”29 On June 29, Carter was listed as one of the new players preparing to make their season debuts for the NAL’s Atlanta Black Crackers.30 After seven appearances, he finally joined Memphis on July 17. “Carter was sick the first of the season and after he recovered, he was so weak and out of condition he wouldn’t report until after the first half,” a newspaper explained. Two days after Carter arrived, the Red Sox released veteran third baseman Zearlee Maxwell.31

After posting the NAL’s best first-half record, the Red Sox faced the second-half champion Black Crackers in the playoffs.32 The series – scheduled as a best of seven – opened with two games in Memphis. The Red Sox won the opener, 6-1, with Carter scoring once and starting a 5-3-2 double play. Neil Robinson was the hitting star, homering twice off Felix “Chin” Evans and collecting five RBIs.33 Carter recalled Robinson as, “about the most valuable player we had on the southern teams. He didn’t do anything flashy; he just got the job done day after day.”34 Memphis won Game Two, 11-6.35 The series was not completed, however, because the Black Crackers failed to show up for the scheduled third contest in Birmingham and failed to secure the use of their usual ballpark in Atlanta. The Memphis Red Sox were officially declared the 1938 NAL pennant winners in December.36

The Red Sox never won another title, but they remained a major attraction. Some Memphis churches altered service times so that parishioners wouldn’t miss the first pitch at Martin Stadium, where patrons dressed in their Sunday best no matter what day it was.37 On the road, Carter recalled, “We were given $2 a day eating fee …and an additional $1 if you had to ride in the bus all night. We might sleep in a bed two nights a week, and the rest of the time we’d sleep, eat, and live in the bus.” He described a restaurant in Tupelo, Mississippi where a sign reading “COLORED” marked the back area where the team was permitted to use a few small tables. “Most of the time, I’d say 80 percent of the time, we’d go to grocery stores. But I loved to play, and what I went through then, I’d go through it again.”38

In late 1939, Carter was part of the Baltimore Elite Giants club that competed against major and minor-leaguers in the integrated California Winter League. “The team we had… was really an all-star team,” he explained. “We had Pepper Bassett, Bill Wright, Jesse Walker, William Harvey, Mule Suttles, James West.”39 In their first league action, the Elite Giants were swept in a doubleheader by the [Joe] Pirrone’s All-Stars squad, but Carter went 3-for-9 against Lee Stine and Julio Bonetti.40 When the Elites hosted the same team on October 18 at Gilmore Field in Los Angeles, they faced a soon-to-be 21-year-old who’d won 24 games for the Cleveland Indians that season while leading the majors in strikeouts. “Despite the opposition of two major previews – “The Roaring Twenties” and “Disputed Passage” – Cleveland pitcher Bob Feller attracted a huge turnout of movie celebrities,” reported Ed Sullivan.41 Feller whiffed 14 in his seven innings, but the Elite Giants scored three times against the bullpen to prevail, 5-2.42 On November 19, Carter tripled in the victory that mathematically eliminated Pirrone’s team.43 He was at shortstop two weeks later when the Elite Giants clinched the championship.44

Carter played mostly third base for the Red Sox in 1940. A Pennsylvania newspaper noted, “Marlin Carter, the regular pepper box of the team, holds down the hot corner and is ever hustling. Carter is a dangerous hitter and one of the fastest men in the league. He is regarded as one of the outstanding hot corner artists in baseball.”45 In July, the Red Sox traveled to Carter’s home state of Texas. At Katy Field in Waco, Memphis rallied to a 2-1 ninth-inning victory over a team featuring Jesse Owens. The four-time gold medalist from the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin raced against a motorcycle after the ballgame.46 Although Carter’s mother still lived in Haslam, Memphis had become his year-round home. The military draft registration card that he filled out that fall listed his occupation as a bell stand at the Hotel Chisca.

In 1941, Carter’s earned praise as “a fine fielder” when he shifted to second base for the bulk of his action.47 When he returned to third base in 1942, his play earned him an invitation to the prestigious East-West All-Star Game. The contest was played on August 16, at Comiskey Park, in front of 45,179 fans.48 Nine Hall of Famers saw action that day – six in the starting lineups. Carter’s West squad featured Cool Papa Bell, Willard Brown, Hilton Smith, Buck O’Neil, and Satchel Paige, while the East had Josh Gibson, Willie Wells, and Leon Day. Paige lost in relief for the West after arriving after the game was underway.49 The West trailed, 3-2, with two on and two outs in the bottom of the seventh when Carter pinch-hit for righty-hitting Parnell Woods against Day, Carter grounded out to Wells at shortstop to end the threat, and Day struck out five of the seven batters he faced to finish off the East’s 5-2 victory.50

Two nights later, the same teams squared off at Municipal Stadium in Cleveland. With the U.S. involved in World War II, the game was a fundraiser for the Army-Navy Relief Fund, attended by 10,791. Carter grounded out against Day again, and the West lost, 9-2. The evening was notable because, for the special occasion, the teams were permitted to use the main lighting system that had previously been reserved exclusively for the Indians’ American League contests.51

Military obligations and player defections to other Negro League clubs cost the Memphis Red Sox eight performers heading into 1943. Team owner Dr. B.B. Martin penned an article that spring describing how a new NNL franchise, the Harrisburg Stars, had advanced Memphis shortstop T.J. Brown $75 to jump teams. “[Brown] left Memphis and went to Mounds, Ill.,” wrote Martin, “returning later with a small capital acting in the role of a scout and carried back with him Red Sox third baseman Marlin Carter.”52

The Stars had originally represented St. Louis, Missouri. In 1941, they represented New Orleans, Louisiana. They disbanded after the 1941 season and regrouped, in 1943, in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Carter joined them on their preseason tour of the Midwest. The Harrisburg Telegraph reported that Carter “has shown up so well that Manager [and third baseman] Harry Williams has decided to give the new player the third base assignment.”53 In July, the same paper said, “Through the early part of the season, Marlin Carter was recognized as a valuable third baseman, both afield and at bat” before he “went back home with an ankle injury.”54

The Memphis Red Sox welcomed Carter back that summer, only to lose him for an even longer period when he was drafted into the U.S. Coast Guard. Before he was honorably discharged as a Steward Third Class, Reserve, in November 1945, he saw Hiroshima and Nagasaki, where atomic bombs had been dropped that August.55

Carter was discharged in St. Louis. “Fred Bankhead was there. So was Ted Radcliffe and some other guys,” he recalled. “We were just waiting around, hoping that we could get back into baseball. I wasn’t there too long before Jelly Taylor came up from Memphis to talk about getting me back with the Red Sox.”56 They all reported to Hot Springs, Arkansas for training in the spring of 1946. Carter signed a contract that paid him $300 per month from May through September.57

When the National Baseball Hall of Fame asked Carter to name his outstanding achievement in baseball after he retired, he named his performance at Yankee Stadium on August 4, 1946. After the Newark Eagles beat the Cleveland Buckeyes in the first game of a Sunday doubleheader, the Red Sox faced the New York Black Yankees in the second contest. In the opening inning, Carter drove a pitch from right-hander Bob Griffith deep to center field, where Felix McLaurin gloved it – but couldn’t hold on. Carter raced around the bases and belly-flopped into home plate with an inside-the-park home run.58 (“It was not charged as an error since [McLaurin] had to back up the terrace and almost crashed into the center field wall.”) Memphis’s Dan Bankhead went on to shut out the Black Yankees, 1-0, also aided by Carter’s defense. “Carter Proves a Robber” was the subhead of one game story, describing how he took away hits from both Griffith and McLaurin after the Black Yankees put two runners aboard in the eighth.59

Jackie Robinson made history on April 15, 1947, by integrating the majors with the Brooklyn Dodgers. Later that season Brooklyn welcomed the majors’ first African American pitcher. Just weeks before Dan Bankhead’s big-league debut at Ebbets Field on August 26, he had pitched for the Memphis Red Sox in two other New York city boroughs with Carter stationed behind him at third base.60 In 1992, Carter reflected, “By the time they began to integrate the major leagues, like so many of the best Negro Leagues players, I was past my prime. They were looking for young players. I was too old to be considered.”61

Carter, 35, finished his major Negro League career with the NAL’s Chicago American Giants in 1948. He was just two days younger than the club’s player/manager, Quincy Trouppe. According to the statistics in Carter’s player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, he appeared in 61 games and batted .281.

When Carter lived in Shreveport, he had attended the Lumpkins Barber College for nine months. Although he wasn’t licensed, he cut hair during the offseason at Radcliffe’s Barbershop on Walker Avenue in Memphis. If the health inspector showed up, he’d hop in a chair and pretend to be a customer, something that happened so many times that the inspector remarked on the “coincidence.” Carter had already married and divorced twice, but at Radcliffe’s he fell in love with a manicurist named Mollie Louise Jackson.62 She was so pretty that a Hollywood recruiter once told her that she would have made a great Scarlett O’Hara in Gone with the Wind had she not been born Black. Marlin and Mollie married at midnight on New Year’s Eve 1948, but only after she converted to Catholicism, the denomination to which he was devoted at the time.63

In 1949, Carter signed with the Rochester Royals of the semipro Southern Minnesota League. African American players were not permitted to shower in the team’s clubhouse. They had to clean up at a firehouse down the street. According to Carter’s daughter, someone saw her father naked there and exclaimed, “My God boy, if I had that, I wouldn’t have to play no baseball!”64

Carter made the circuit’s All-Star team and batted .380.65 Upon returning to Rochester in 1950, he hit .303.66 He spent one night in the hospital following an August 6 beaning.67 That fall, he joined Jackie Robinson and Roy Campanella for a barnstorming tour.68

Carter was listed as a reserve for the Memphis Red Sox in 1951, his final season.69 In 1958, his photo appeared in the New York Herald Tribune as the team’s manager when they played at Yankee Stadium.70 One of Carter’s players that summer was Charley Pride. The future Grammy Award winner and Country Music Hall of Fame inductee went 7-3 as a pitcher.71

When Carter’s wife Mollie became pregnant with their daughter Marilyn, she had to quit her job as a public-school teacher according to Memphis’s laws at the time. Carter landed a full-time position with International Harvester, manufacturers of farming equipment. Marilyn cherished the times they’d share cake and ice cream when he returned from his shift late at night.72

In Memphis, Negro Leaguers were major celebrities. Carter was handsome, and he loved women as much as they loved him. He divorced Mollie in 1957, and wound up in Chicago with his fourth wife, June Tucker, to whom he was married from 1959 to 1969. But when Marilyn visited her father as a teenager, she could tell it was an unhealthy arrangement. Little by little, Carter dropped off items of clothing at the cleaners until, one day, he picked them all up and drove back to Tennessee to reconcile with Mollie.73

Carter found work as the head locker room attendant at the Colonial Country Club in Cordova. While he was initially puzzled by the way the members gambled away their money over the movements of a little ball, he started playing golf himself in 1972, as part of an all-Black group called the “Duffers.” They played with purpose, organizing an annual tournament and donating the proceeds to the WICC program that provided diapers and baby food to young, needy mothers.74

Carter and Mollie split up again, but Marilyn visited her father every Sunday after church. He drank his Scotch neat, loved smoking cigars, and enjoyed watching all types of sports on television. Two former teammates, Verdell Mathis and Joe Scott, were frequent companions.75

In 1989, the Atlanta Braves teamed up with Southern Bell to reunite dozens of former Negro Leaguers for a three-day weekend. Many of the ballplayers were flown in, but Carter joined the group from Memphis and Birmingham that traveled by bus as they had in their playing days – albeit on a state-of-the art Greyhound with recliners, video screens, and a restroom. In the New York Times article about their journey, Carter joked that the bus would break down on the way, just like the Memphis Red Sox’s transportation of old.76 Between games of a June 5 doubleheader against the reigning World Series champion Dodgers, he was one of 81 Negro League veterans introduced on the field at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium. Los Angeles manager Tom Lasorda called them “Without a doubt, the greatest guys who ever played baseball.”77

Carter participated at the Heroes of Baseball exhibit at the 1992 All-Star Game in San Diego.78 But a New York Times article the following spring detailed how many of the Negro Leaguers were often disappointed by the appearance fees they received to sign autographs at similar events, compared to what they were promised, or expected.79 Decades after his last game, Carter appeared on his first baseball cards. In response to fan mail, he often penned hand-written replies. “I have maybe 500 photos of ball players,” he wrote, before closing with his signature “Yours in sport, Marlin Carter.”80

On December 21, 1993, Carter died from a staph infection at the Memphis VA Medical Center. As his body exited the Metropolitan Baptist Church following his funeral, “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” was played on the sanctuary’s grand pipe organ. He was buried in the city’s historic Elmwood Cemetery on what would have been his 81st birthday. When people dress up as the famous occupants of the graves at Elmwood for a fundraiser each year, somebody dons a Memphis Red Sox uniform and tells Carter’s story.81

“Like everything else, playing baseball had its high points and its low points. The low points were mostly about being poor, not getting paid what you were due. And, we had to play in some really terrible places in Negro baseball,” Carter said. “But… I got to play in some of the biggest and best ballparks in the country – Yankee Stadium, Comiskey Park and others – with major league size crowds. I got to play against, and alongside, some of the best players that ever played. … And there were a lot of fun times.”82

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Marilyn Carter Williams (telephone interview with Malcolm Allen, January 31, 2022, and several follow ups).

The author would also like to thank Cassidy Lent from the Giamatti Research Center at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum and SABR colleague Rich Puerzer for research assistance.

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Keith Thursby and fact-checked by Tony Oliver.

Sources

In addition to sources cited in the notes, the author consulted www.ancestry.com and www.baseball-reference.com, https://sabr.org/bioproject, and https://seamheads.com/blog/.

Notes

1 Although the Kansas City Monarchs had the NAL’s best overall record in 1938, first-half champions Memphis defeated the second-half winners, the Atlanta Black Crackers, in the playoffs.

2 The town of Haslam, two miles northeast of Joaquin in Shelby County, was officially incorporated in 1913.

3 Cecil Harper Jr., “Haslam, TX,” Texas State Historical Association, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/haslam-tx (last accessed February 2, 2022).

4 “Keen Racial Feeling Develops at Texas Mill Town and Trouble is Feared,” Times-Democrat (New Orleans, Louisiana), December 9, 1913: 10.

5 Marlin Carter, Publicity questionnaire his player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

6 Prentice Mills, Black Ball News Revisited, (Middletown, Delaware: Red Opel Books, 2019): 99.

7 Mills, Black Ball News Revisited: 99-100.

8 Mills, Black Ball News Revisited: 100.

9 Mills, Black Ball News Revisited: 102.

10 In 1929, the circuit was called the Texas-Oklahoma-Louisiana League.

11 Carter, Publicity questionnaire.

12 Mills, Black Ball News Revisited: 102.

13 Mills, Black Ball News Revisited: 103.

14 Mills, Black Ball News Revisited: 106.

15 The original Negro National League (1920-1931) had ceased operations dues to the Great Depression and the newly formed East-West League folded in June.

16 Mills, Black Ball News Revisited: 107.

17 “Harvey in No-Hit No-Run Game,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 15, 1933: 15.

18 William J. Plott, The Negro Southern League: A Baseball History, 1920-1951, (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2005): 44-47

19 “Red Sox Win,” Pittsburgh Courier, September 2, 1933: 14.

20 Walter E. Dobbins, “Links Drop Scuffle to Memphis Red Sox,” Nebraska State Journal, July 10, 1934: 9.

21 United Press, “Memphis Red Sox Win Ball Tourney,” Hastings (Nebraska) Daily Tribune, September 10, 1934: 5.

22 Mills, Black Ball News Revisited: 107.

23 Hubbard won the broad jump at the 1924 Summer Games in Paris.

24 Jeff Suess, “Cincinnati’s Unheralded Players in Negro League Baseball,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 31, 2021, https://www.cincinnati.com/story/sports/2021/07/31/history-negro-league-baseball-cincinnati-black-players/5416640001/ (last accessed February 2, 2022).

25 “Cincinnati Tigers Win Over Shastas in Exhibition Tilt,” Edmonton (Alberta, Canada) Bulletin, August 29, 1935: 14.

26 Suess, “Cincinnati’s Unheralded Players in Negro League Baseball.”

27 Ross Forman, “Former Negro League Infielder Marlin ‘Pee wee’ Carter Dies at 80,” Sports Collectors Digest, January 28, 1994.

28 “The Tigers’ Tale,” MLB.com, https://www.mlb.com/reds/hall-of-fame/history/cincy-tigers (last accessed January 28, 2022).

29 Mills, Black Ball News Revisited: 108.

30 “Black Crackers to Show New Players Against Jax,” Atlanta Daily World, June 29, 1938: 5.

31 Sam R. Brown, “Red Sox Take Road,” Atlanta Daily World, July 23, 1938: 5.

32 Like Major League Baseball’s split 1981 season, when the Cincinnati Reds did not qualify for the postseason despite posting the National League West’s best overall record, the Kansas City Monarchs missed the 1938 NAL playoffs despite compiling a better overall mark than both Memphis and Atlanta.

33 “Memphis Routs Atlanta in Opener, 6 to 1,” Atlanta Daily World, September 19, 1938: 5.

34 Monte Irvin, Few and Chosen Negro Leagues: Defining Negro Leagues Greatness, (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2007).

35 “Black Crackers Play Birmingham Sunday,” Atlanta Constitution, September 24, 1938: 22.

36 “Memphis Gets 1938 American League Pennant,” Chicago Defender, December 17, 19338: 9.

37 Marilyn Carter Williams, Telephone interview with Malcolm Allen, January 31, 2022 (Hereafter Carter Williams-Allen interview).

38 Leslie A. Heaphy, The Negro Leagues 1869-1960, (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2013).

39 Mills, Black Ball News Revisited: 109.

40 “Pirrone’s All-Stars Stifle Giants Twice,” Los Angeles Times, October 9, 1939: A12.

41 Ed Sullivan, “Hollywood,” Daily News (New York, New York) October 22, 1939: 30.

42 James Newton, “Bob Fellers Fans 14, But Elites Win, 5-2,” Afro-American (Baltimore, Maryland), October 21, 1939: 21.

43 James Newton, “McDuffie, Harvey Hurl Winning Ball on Coast,” Chicago Defender, November 25, 1939: 22.

44 James Newton, “Giants Win Winter League Title,” Chicago Defender, December 9, 1939: 24.

45 “Famous Memphis Red Sox Play Here Tomorrow Night,” Delaware County Daily Times (Chester, Pennsylvania), August 6, 1940: 11.

46 “Negro Lad Tires on Mound to Give Red Sox 2-to-1 Win,” Waco (Texas) News-Tribune, July 19, 1940: 10.

47 Daniel, “North-South Play in Stadium Sunday,” New York Amsterdam Star-News, August 9, 1941: 18.

48 “East All-Stars Win from Paige and West, 5 to 2,” Chicago Tribune, August 17, 1942: 19.

49 “East Defeats West in Negro Classic,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, August 17, 1942: 18.

50 Frank A. Young, “48,000 See East All-Stars Beat Paige and West,” Chicago Defender, August 22, 1942: 19.

51 “10,791 See East All-Stars Beat West at Stadium,” Cleveland Call and Post, August 22, 1942: 11.

52 Dr. B.B. Martin, “Posey Charges American League Violated Agreement,” Michigan Chronicle, May 8, 1943: 20.

53 “Stars Arrive in Town for Games at Island,” Harrisburg Telegraph, May 15, 1943: 9.

54 “Hans Wagner’s 9 will Battle Stars in Doubleheader,” Harrisburg Telegraph, July 10, 1943: 8.

55 Dave Barr, “Negro Leagues Players Played Major Role in World War II,” Monarchs to Grays to Crawfords, November 11, 2014, https://nlbmmlb.wordpress.com/tag/ted-williams/ (last accessed February 2, 2022).

56 Mills, Black Ball News Revisited: 110.

57 Carter’s daughter, Marilyn Carter Williams, graciously shared a photograph of the contract with the author.

58 Haskell Cole, “Memphis, Eagles Win Games in New York,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 10, 1946: 17.

59 “Drama and Color in Tight Yankee Stadium Baseball Duels Before 13,000 Fans,” New York Amsterdam News, August 10, 1946: 13.

60 Bankhead pitched 12 innings for Memphis at Yankee Stadium in the Bronx on August 10 and started at Dexter Park in Queens on August 13. Haskel Cole, “Yanks, Sox in 2-2 Tie,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 16, 1947: 14., “Memphis Red Sox Check Bushwicks,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 14, 1947: 18.

61 Mills, Black Ball News Revisited: 111.

62 According to the questionnaire that Carter filled out for the Hall of Fame, his first two wives were Edna Turner (1936-1940), and Gertrude Givens (1941-1945).

63 Carter Williams-Allen interview.

64 Carter Williams-Allen interview.

65 Augie Karcher, “New Manager Ends Lengthy Speculations,” Winona (Minnesota) Republican-Herald, November 29, 1949: 14.

66 Augie Karcher, “Behind the Eight Ball,” Winona Republican-Herald, September 7, 1950: 20.

67 “Carter Okay, Say Doctors,” Winona Republican-Herald, August 7, 1950: 13.

68 Augie Karcher, “Behind the Eight Ball,” Winona Republican-Herald, October 5, 1950: 20.

69 “Red Sox Opened Second Half of Season July 4 Against the Elite Giants,” Atlanta Daily World, July 7, 1951: 5.

70 “First Ball,” New York Herald Tribune, June 2, 1958: B3.

71 Bob LeMoine, “Charley Pride,” Society for American Baseball Research Biography Project, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/charley-pride/ (last accessed February 5, 2022).

72 Carter Williams-Allen interview.

73 Carter Williams-Allen interview.

74 Carter Williams-Allen interview.

75 Carter Williams-Allen interview.

76 Malcolm Moran, “A Sentimental Journey for the Negro Leagues,” New York Times, June 5, 1989: C3.

77 Marilyn Milloy, “‘Every One of Us Could Have Made the Major Leagues,’” Newsday (New York, New York, New York), June 7, 1989: A3.

78 Martin Henderson, “Green Now Relishes His Place in History Books,” Los Angeles Times, July 13, 1992: 9B.

79 Richard Sandomir, “Baseball Gold Still Eludes Jim Crow’s Victims,” New York Times, March 15, 1993: A1.

80 Marlin Carter, Letter to Mr. Milazzo, February 12, 1993.

81 Carter Williams-Allen interview.

82 Mills, Black Ball News Revisited: 111.

Full Name

Marlin Theodore Carter

Born

December 27, 1912 at Haslam, TX (USA)

Died

December 20, 1993 at Memphis, TN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.