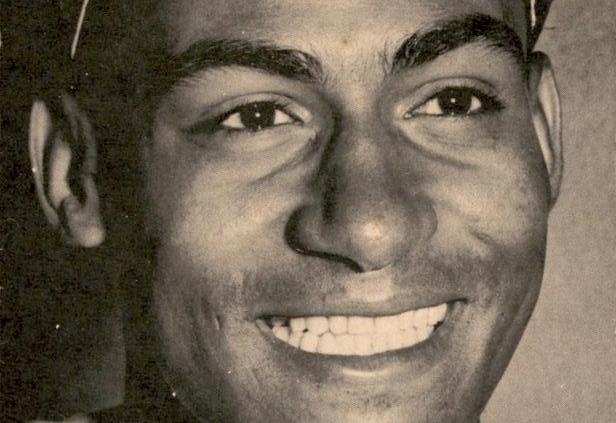

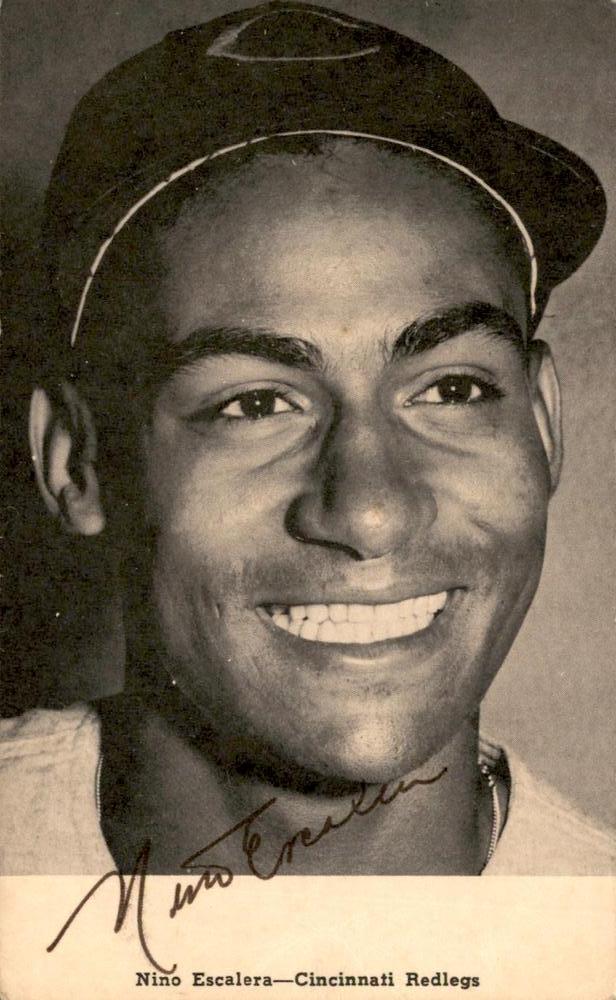

Nino Escalera

It took 72 years for the first Black man to play for the Cincinnati Reds. The second one arrived merely minutes after the first.

It took 72 years for the first Black man to play for the Cincinnati Reds. The second one arrived merely minutes after the first.

The franchise, one of the National League’s founding clubs, has a complicated record on racial matters. Despite being very early to appreciate the quality of white Cuban players — Armando Marsans, Rafael Almeida, Mike González, and Dolf Luque, all debuted for the club in the 1910s. The team still had not yet fielded a dark-skinned man seven years after Jackie Robinson’s debut. The city’s proximity to the “Border States” — not part of the Confederacy but nevertheless less progressive in racial tolerance — likely played a role. The sport’s laborious march toward integration finally reached the team in 1954, with two Black players on the Opening Day roster.

On April 17, in their third game of the season, the Reds — then known as the Redlegs — officially joined their peers by using Nino Escalera and Chuck Harmon as consecutive pinch-hitters in the seventh inning.1 It was a humble beginning for a franchise that would ultimately feature Hall of Famers Frank Robinson, Joe Morgan, and Barry Larkin among its all-time greats.

For Escalera, whose last name translates to “ladder” in Spanish, it was a fitting zenith, given his lengthy voyage through various minor-league levels. The first baseman-outfielder spent just that one season in the majors but played on in Triple-A through 1962. During that time, he became a manager in winter ball in his homeland, Puerto Rico. He then went on to be a noteworthy coach and scout.

Saturnino Escalera was born on November 29, 1929, in Santurce, a section of San Juan, Puerto Rico.2 His father, Antonio Escalera, worked as a master plumber while his mother, Berta Cuadrado, was a homemaker. Saturnino, known affectionally as “Nino,” had nine siblings. One of them, José, also played professional baseball on the island. José and Nino were seldom found without a bat in their hands, though it was rarely a store-bought model — more commonly a broomstick. They played ball with their neighbors on Aponte Street. Nino was his grandfather Florentino’s favorite grandson, so his family also called the youngster “Flor.” He began turning heads in the “Future Stars” league for 12-to-15 year old boys, displaying his talent at first base. He fashioned his fielding after Negro League star Buck Leonard, who played with the Mayagüez Indios (Indians) in 1940-1941, leading the league with a .390 average. The left-handed first basemen also shared a kind demeanor on and off the field.

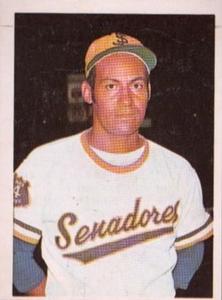

In 1945, when he was not yet 16 years old, Escalera played for the San José of Río Piedras club of the then-amateur Liga de Béisbol Superior Doble A. His strong performance earned him a spot on the island’s team for the World Amateur Baseball Tournament, held in 1947 in Cartagena, Colombia. Although he had signed a contract with the professional San Juan team, “there was a rule then that you could play amateur ball for two weeks after signing.”3 He was selected as the competition’s most valuable player. Fresh off his graduation from Santurce’s Central High School, Escalera joined the Senadores days shy of his 18th birthday and hit an impressive .337 over 95 at-bats. As an adult, Escalera was 5’10” and weighed 165 pounds, a trim build he kept well into old age.

His performance was noticed by the New York Yankees. They signed Escalera and assigned him to the Class B Bristol Owls of the Colonial League on July 4, 1949. Despite being one of the circuit’s youngest players, the lefty-hitting Escalera dominated the competition with a .368 average, .517 slugging percentage, and ten triples over 129 games across two seasons. He also spent half a year with the Class C Amsterdam Rugmakers, blistering opposing hurlers with a .337 average. He returned to Puerto Rico in the off-season, playing in both the winter league and in exhibition games (“partidos amistosos”). The legendary Francisco “Pancho” Coímbre chose him for a series against the Antillean Brewing (“Cervecería Antillana”) Company squad in the Dominican Republic. With great pride he recalled, “Pancho went to my family’s house and asked my dad for permission … my dad said yes.”4

In early 1951, he reported to the Class A Central League Muskegon Reds, with whom he clubbed 16 home runs and batted .374 (both career bests), before struggling with Class AAA Syracuse of the International League (batting only .236 in 20 games).

Nevertheless, with three strong seasons, things were looking up for Escalera. He was assigned to the Kansas City Blues, the Yankees’ Triple-A team in the American Association. That December, The Sporting News reported that Cincinnati GM Gabe Paul was interested in obtaining both Chuck Harmon and Escalera to be the organization’s first Black players.5 However, in January 1952, Kansas City sold Escalera’s contract to Toledo, a Chicago White Sox affiliate, also in the American Association.

The AA itself faced multiple team relocations in the early ’50s. The Toledo club would move to Charleston, West Virginia, during the 1952 season (the Milwaukee Brewers, displaced by the incoming National League Boston Braves, shifted to Toledo, as did the Sox the following year). While the musical chairs were happening, the Mud Hens sold Escalera’s contract to the Reds on June 16, with an agreement to retain him for the remainder of the season. Escalera slumped to .249/.329/.336 despite playing 148 games.

After the season, he returned to Puerto Rico to prepare for winter ball. He also married his first wife on September 27, Nellie Latorre, with whom he had four children: Adrián Saturnino (known as Nino Jr.), Nereida, Gerardo, and Edgardo.6 The family would typically move to wherever Escalera was playing until the children started school. The companionship helped reduce the loneliness and alleviate the sting of many racially charged incidents. Escalera and his dark-skinned teammates were often denied service at restaurants.

Escalera spent nearly all of the 1953 season in the Double-A Texas League. (He played briefly on option with Indianapolis, a Cleveland Indians farm club, in April.7) He appeared in 133 games with the Tulsa Oilers, producing a .305 batting average and showing a discerning eye at the plate. His 35 strikeouts were dwarfed by his 72 walks. More than 700 miles away, the Cincinnati front office noticed its prospect’s performance and made other plans for the upcoming season.

The Cincinnati franchise was mired in mediocrity. The team’s last winning season had come in 1944, and despite the prowess of sluggers Gus Bell and Ted Kluszewski, its outlook wasn’t bright. As the 1954 season began, excitement grew over Harmon and Escalera. Both had impressed the front office during spring training enough to merit their inclusion on the big-league roster. Escalera closed camp with aplomb on April 11, clubbing a three-run home run against the Detroit Tigers in one of the last exhibition games, to provide the margin of victory in an 8-5 Reds win.8

Eager to prove his worth, Escalera sat on the bench during the team’s first two games, awaiting his chance. His April 17 debut was modest. Down by four runs, the Redlegs sent a trio of pinch-hitters to the plate in the top of the seventh inning, giving all three their season debuts. More than half a century later, the Cincinnati Enquirer would rank the game as the 17th most important in the franchise’s history, yet contemporary reporting stated only “Escalera batted for [Andy] Seminick and singled. Harmon went up for [Corky] Valentine. He popped to Joe] Adcock.”9

Escalera’s subsequent appearances proved sporadic. Blocked by slugger Kluszewski at first and productive outfielders Jim Greengrass and Bell, Escalera sat on the bench for long stretches. His first five appearances — three singles, one walk, one groundout — were all as a pinch hitter. On April 28, starting in right field, he went hitless in three at-bats but managed a sacrifice fly to register his first run batted in. He also reached on an error and stole second base, though he was unable to score. His average had dipped to .190 by May 22, when his name entered the record books in a peculiar, unexpected way.

Modern fans have grown accustomed to defensive shifts dictated by the abundance of advanced analytics. In an earlier era, shifts were typically employed only against big stars like Ted Williams and Stan Musial. Reds manager Birdie Tebbetts, nursing a two-run lead but with the Cardinals’ Red Schoendienst on first and Musial at the plate, lifted starting shortstop Roy McMillan for Escalera. No left-hander had played shortstop in the major leagues since 1905, when Hal Chase took that field position for two games with the American League Highlanders. In the subsequent 66 years, no one has repeated Escalera’s feat.10 Other players have been listed as shortstops in lineups, only to be removed after a plate appearance before taking the field.11

The box score, however, obscures the details behind the move. Escalera’s cleats did not touch the infield dirt. He was stationed not in the traditional shortstop location, but rather as a fourth outfielder, between center fielder Bell and right fielder Wally Post. The peculiar gambit paid off. Musial, perhaps distracted by the defensive alignment, promptly struck out. According to The Sporting News, “umpire Dusty Boggess, working first base, called a halt, thinking the Reds had too many players on the field” before acknowledging that only nine men were present.12 Tebbetts explained that if Musial “should single through our unprotected shortstop position that would be all right,” rather than give the Cardinal great the opportunity to hit for extra bases.13

While Escalera’s career may not have granted him admission into Cooperstown, he played on Doubleday Field on August 9, 1954 as the Reds battled the Yankees in the 13th “Hall of Fame Game.” He doubled in the third inning, advancing Harmon to third base, before they both scored during Cincinnati’s five-run outburst. The Bombers eventually took a 10-9 lead in the final frame; Escalera came to bat with the bases loaded and two outs but struck out to end the game.14 Nevertheless, it was a remarkable achievement. He was the first Puerto Rican to play in the annual exhibition.15

Escalera’s year-end totals of 73 games, 77 plate appearances, 15 runs, 11 hits with a .159 batting average were disappointing. He seldom played in consecutive games and was frustrated by his lack of opportunities. If not on the field, he believed, he should be honing other skills and thus became vocal about suggesting in-game moves. The Reds saw a match for Escalera with Bobby Maduro’s newly relocated Havana Sugar Kings. Maduro dreamed of a possible major league team in Cuba and saw Triple-A success as a preliminary step. Upon purchasing the International League’s Springfield franchise, he moved the club to Havana. Its affiliation with the Washington Senators ended, giving Cincinnati a path to renew its old Cuban connection.

Under the tutelage of Reggie Otero (1955) and Nap Reyes (1956-1958), Escalera played consistently, splitting time between first base and the outfield. He relished the atmosphere — tropical, baseball-mad — and racially integrated, a stark difference from his years in the lower minor leagues.16 Cuba and Puerto Rico were similar environments. His first season, punctuated by a .297 average and 29 doubles, proved to be Escalera’s best, but he was nevertheless a regular for his four campaigns and was an IL All-Star in 1958. His teammates included aging Cuban stars Connie Marrero and Sandy Consuegra (also major-league veterans) and promising youngsters Mike Cuellar and Tony González, who would eventually reach the big show. Escalera mingled with Cuban society, becoming a regular at the landmark “Alí Bar” with singer and owner Benny Moré.

On December 3, 1958, the Reds traded Nino to the Pittsburgh Pirates for fellow Puerto Rican Luis Arroyo. The lefty reliever had spent the year in the minor leagues after playing a few seasons with the parent club. Escalera delivered three solid campaigns for the Columbus Jets of the International League, patrolling the outfield and occasionally manning first base. Off the field, the family rented the second floor of a large house; Díomedes “Guayubín” Olivo occupied another floor. At the conclusion of the 1961 season, Escalera was released by Pittsburgh but received a contract from the Baltimore Orioles. His 1962 year was his last in the minor leagues. A .239 average in 83 games prompted the Rochester Red Wings to move in a different direction after the season ended.

Escalera continued to play winter baseball in Puerto Rico. While active, he also managed San Juan in 1959-1960, leading the club to its best record in two decades and to the championship series. His elevation to skipper was well-received by the fans. They cherished his play for the capital’s long-suffering franchise. Before the season began, a tongue-in-cheek article stated, “I don’t know whether to congratulate you or to offer my condolences for what is in store … the odds are stacked against you, but you can win. And the least we can do is to help you, to return a little bit of what you have given us.”17 After 16 seasons with San Juan from 1947-48 to 1962-63, he spent a final one with Caguas, a club he would later pilot to the league title in the 1967-1968 tournament.

Escalera continued to play winter baseball in Puerto Rico. While active, he also managed San Juan in 1959-1960, leading the club to its best record in two decades and to the championship series. His elevation to skipper was well-received by the fans. They cherished his play for the capital’s long-suffering franchise. Before the season began, a tongue-in-cheek article stated, “I don’t know whether to congratulate you or to offer my condolences for what is in store … the odds are stacked against you, but you can win. And the least we can do is to help you, to return a little bit of what you have given us.”17 After 16 seasons with San Juan from 1947-48 to 1962-63, he spent a final one with Caguas, a club he would later pilot to the league title in the 1967-1968 tournament.

He developed a deep friendship with Roberto Clemente, who had joined the Senadores for the 1959-1960 season, a bond that would last until the “Great One’s” death. His son Adrián reminisced. “Roberto would just drop by and just talk about baseball on the front porch. Once people realized that, there were big traffic jams on the street from people wanting to get a glimpse. They would stay at the stadium after games, going over the plays … whenever Clemente managed in Puerto Rico, he would ask my dad to be one of his coaches.”18 In fact, Clemente accepted the San Juan managerial job for the 1970-1971 season conditionally upon Escalera joining the coaching staff. The latter recalled, “Clemente told me I was the ideal person, given our friendship, to help him. He asked me, as a favor, to help him manage. Although I had already managed San Juan and Caguas, at that time I was distanced from baseball in Puerto Rico. And due to our friendship, I helped him.”19

Escalera currently ranks third in the PRWL’s all-time rankings in hits (1,071) and runs scored (646), seventh in total bases (1,409), fourth in doubles (155, tied with Víctor Pellot, a/k/a Vic Power), and second in triples (66, tied with Luis “Canena” Márquez).20 Beloved by fans, he was honored in a ceremony at Parque Sixto Escobar for his service with the team. A fan-led donation drive paid off his home mortgage. Playing for the franchise, he enjoyed two league titles, 1951-1952 and 1960-1961.

Known as “el caballero de la inicial” (the gentleman of first base) for his even keel and kind temperament, Escalera long believed to have been ejected from only one game in his long career. On January 23, 1962, San Juan was playing Arecibo in a one-game tiebreaker for the final playoff spot. With the score tied 3-3, Clemente hit a grounder up the middle destined for a close play at first. According to Escalera, umpire Mel Steiner signaled an out before the ball reached the base.21

The umpire, engaged in a heated discussion with Senadores skipper Reyes, allegedly told the manager to “go back to Cuba.”22 Ever mindful of racial and ethnic discrimination and unwilling to accept it on his native land, Escalera joined Reyes in pummeling the arbiter, who suffered an injury to his left arm.23 Reyes was fined $100 and suspended for three weeks of the next season while Escalera was punished less harshly. He received a $50 fine and a 10-game suspension. The contest would be the last held in Parque Sixto Escobar before San Juan and Santurce both moved to Hiram Bithorn Stadium, after its construction in 1962.

However, SABR member Tom Van Hyning discovered a prior instance a year earlier. On December 28, 1960, after rounding second after a pinch-hit double, Escalera was thrown out by Frank Howard. Escalera felt he was safe, vehemently arguing his point to umpire Bob Burns, who tossed both the player and third-base coach Félix “Fellé” Delgado.24

Escalera was one of the founding members of Asociación de Peloteros Profesionales de Puerto Rico, the players’ union, much to the chagrin of the team owners. Much like its major-league counterpart, the uneasiness between the two factions led to some participants, including Escalera, being blackballed and passed over for hard-earned opportunities. His son recalls, “My dad lost his job; I had to be pulled from my private school. He purchased a truck and began working at the docks before working up to be a supervisor with Refrescos Fría, a local soft-drink company. He returned to baseball when the owner of the Cataño Double A franchise, Joaquín Martínez Rousset, hired him as the team manager in 1964.”25 He moved to the Guerrilleros (Warriors) of Río Grande in 1965 and piloted the Puerto Rican national team in various amateur competitions.

Al Jackson, who spent several years with the New York Mets, was instrumental in connecting Escalera to the organization. The former Columbus teammates had remained close and Jackson was aware of Escalera’s baseball acumen. Escalera became a scout for the New York Mets organization (1967-1981) and the San Francisco Giants (1981-1983), covering the Caribbean region. He signed Mario Ramírez, Benny Ayala, Ed Figueroa, Jerry Morales, Juan Berenguer, Teodoro (Ted) Martínez, Alex Treviño, José Oquendo, and Al Pedrique.

After his playing career, Escalera divorced Nellie and married Carmen Ivia. Meanwhile, the family continued to produce baseball players. His nephews Rubén Escalera and Alfredo Escalera played across the minor and Caribbean leagues but did not reach the majors. Rubén also managed the Arizona Fall League’s affiliate of the Oakland Athletics and served as a Caribbean scout for the organization.

Although he did not appear on a baseball card, Escalera was part of a limited-edition issue of coins commemorating the first 20 Puerto Rican-born major league players. The set was produced in 2010 to celebrate the Mets-Marlins regular season games at Hiram Bithorn Stadium.

On November 13, 2013, Escalera was recognized as one of the Puerto Rican Professional Baseball League’s best 75 players. Eight journalists and the league’s historian, SABR member Jorge Colón Delgado, selected the players to commemorate the circuit’s 75th year.26 Escalera was one of 11 honorees to be in attendance. Previously he was enshrined in the Puerto Rico Baseball Hall of Fame (1992), Río Piedras Sports Hall of Fame (1997), Puerto Rico Sports Hall of Fame (1983) and Santurce Sports Hall of Fame.27

SABR member and Puerto Rican historian Néstor Duprey, who serves as an unofficial historian for the San Juan Senadores, regards Escalera as a “key member of the 1950s club which brought the second title to San Juan … he was the most important native player for the franchise before Clemente arrived in 1960. As a manager, he led the rebuilding Caguas team to the 1968 championship. The club was led by the fourth generation of Puerto Ricans in the big leagues … Eliseo Rodríguez, Guillermo (Willie) Montáñez, Félix Millán, Eduardo Figueroa. Nino was able to draw the best out of this young talent; to me, this was his peak as a professional manager. He was always a gentleman, a smart baseball man with a lot of baseball maturity as both a manager and a player.”28 Among Puerto Rican baseball fans, he is regarded as one of the three best first basemen produced by the island, along with Orlando Cepeda and Power, who enjoyed greater Stateside glory.

On July 3, 2021, Nino Escalera passed away in an assisted living facility. At the time of his death, he was the oldest living major-league baseball player from Puerto Rico.29 Juan Flores Galarza, PRWL President, stated, “We greatly lament the passing of one of the best players our league has ever had. He was good both on and off the field.”30

Acknowledgments

- Luis Rodriguez Mayoral for connecting the author with the Escalera family.

- Diana Escalera for providing information about her brother Nino Escalera.

- José Escalera for providing information about his uncle Nino Escalera.

- Adrián Nino Escalera for providing information about his father Nino Escalera.

- Jossie Alvarado for connecting the author to Néstor Duprey.

- Néstor Duprey and Raúl Ramos for providing information about Nino Escalera.

- Ángel Colón for providing the 2011 SABR Puerto Rico-Orlando Cepeda Chapter publication “Nino Escalera: El Caballero de la Inicial.”

- SABR members Joey Beretta, Bill Deane, William Hickman, and Andrew Milner for providing information on the 1943 and 1951 Hall of Fame games.

- National Baseball Hall of Fame researchers Bruce Markusen and Craig Muder for providing information on the 1951 Hall of Fame game.

- SABR member J.G. Preston for his in-depth article on left-handed third basemen, second basemen, and shortstops.

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello, Bruce Harris, and Jonathan Greenberg and checked for accuracy by SABR’s fact-checking team.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author relied extensively on Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 “Black Famous Baseball Firsts,” Baseball Almanac, http://www.baseball-almanac.com/firsts/first8.shtml.

2 The Sporting News player contract card cites November 29, a fact Escalera confirmed during an interview with Frank Otto on February 1, 1993. However, Escalera noted that the official register shows December 1 owing to a delay in the official registration.

3 Thomas Van Hyning, Puerto Rico’s Winter League (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2004), 125.

4 Raúl Ramos, Los Bates Grandes Se Respetan (Self-published book, 2019), 73.

5 “Reds May Take On First Negro Farmhands in ’52,” The Sporting News, December 12, 1951: 18.

6 The Sporting News Player Contract Card.

7 “Inactivity Hurts Tribe Slab Corps,” Indianapolis Star, April 18, 1953: 18.

8 “Exhibition Games: Tigers-Reds Series,” The Sporting News, April 21, 1954: 36.

9 Mark Schmetzer, “Top games in Cincinnati Reds history: No. 17: Nino Escalera and Chuck Harmon integrate team,” Cincinnati Enquirer, Aug 22, 2019, http://cincinnati.com/story/sports/mlb/reds/2019/08/22/reds-150th-anniversary-nino-escalera-chuck-harmon-debut-dolf-luque-birdie-tebbetts-ted-kluszewski/2087071001/.

10 J.G. Preston, “Left-handed throwing second basemen, shortstops, and third basemen,” The J.G. Preston Experience, June 22, 2013, http://prestonjg.wordpress.com/2009/09/06/left-handed-throwing-second-basemen-shortstops-and-third-basemen/.

11 http://www.baseball-reference.com/blog/archives/10835.html.

12 Tom Swope, “Birdie Tries Novel Shift Against Stan—Four Outfielders,” The Sporting News, June 2, 1954: 9.

13 Tom Swope.

14 “1954 Hall of Fame Game,” The National Baseball Hall of Fame Museum, http://www.baseballhall.org/discover-more/stories/hall-of-fame-game/1954.

15 Although Luis Rodríguez Olmo (1943) played for the Brooklyn Dodgers when the franchise appeared in the Hall of Fame Game, he did not see action in the contest, according to the box score from the July 22, 1943 edition of The Sporting News.

16 John Harris and John Burdbridge, “The Short but Exciting Life of the Havana Sugar Kings,” The National Pastime: Baseball in the Sunshine State, 201, http://www.sabr.org/journal/article/the-short-but-exciting-life-of-the-havana-sugar-kings/.

17 Rafel Pont Flores, “El Deporte en Broma y en Serio: Carta a Nino,” Periódico El Mundo, August 24, 1959: 18. Reprinted in “Nino Escalera: el Caballero de la Inicial,” by the SABR Puerto Rico-Orlando Cepeda Chapter, 2011.

18 Author’s personal telephone interview with Adrián Escalera, December 6, 2020.

19 Néstor R. Duprey Salgado, Clemente: En la víspera de a gloria (Self-published book, 2017), 32.

20 Saturnino “Nino” Escalera statistics and profile, Béisbol101, http://beisbol101.com/saturnino-nino-escalera/.

21 Van Hyning, 64.

22 Van Hyning, 64.

23 “Steiner Tiene Una Lesión en el Hombro,” Periódico El Mundo, January 24, 1962, http://www.facebook.com/groups/ccprsf/permalink/2597585513624740/.

24 Thomas Van Hyning, “Nino Escalera ejected twice (not once) in the Puerto Rico Professional Baseball League,” July 6, 2021, Béisbol101.com, https://www.beisbol101.com/nino-escalera-ejected-twice-not-once-in-the-puerto-rico-professional-baseball-league/.

25 Author’s personal telephone interview with Adrián Escalera.

26 Edna García, “LBPR escoge a los 75 jugadores más destacados,” November 14, 2013, http://www.ligapr.com/lbprc-escoge-a-los-75-jugadores-mas-destacados/.

27 Salón de la Fama del Deporte Riopedrense, http://www.famadeportesrp.org/exaltados/perfiles/1997/saturnino.html, Pabellón de la Fama del Deporte Puertorriqueño, http://www.pabellondelafamadeldeportepr.org/directorio_de_imortales.html.

28 Author’s personal telephone interview with Néstor Duprey, April 7, 2021.

29 Emilio “Millito” Navarro, who died April 30, 2011, at age 105, was the oldest former professional baseball player and last surviving player from the American Negro League, but he did not play Major League Baseball.

30 “La liga invernal de beísbol lamenta muerte de Nino Escalera, primer pelotero negro en jugar con los Reds de Cincinnati,” El Nuevo Día, July 3, 2021, https://www.elnuevodia.com/deportes/beisbol/notas/la-liga-invernal-de-beisbol-lamenta-muerte-de-nino-escalera-primer-pelotero-negro-en-jugar-con-los-reds-de-cincinnati/.

Full Name

Saturnino Escalera Cuadrado

Born

November 29, 1929 at Santurce, (P.R.)

Died

July 3, 2021 at Las Piedras, (P.R.)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.