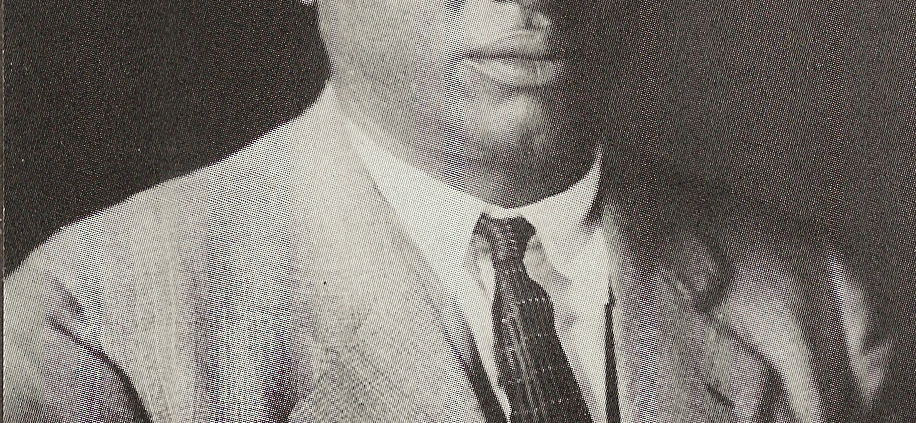

Tom Wilson

A significant event in Nashville’s Black community took place on Tuesday, February 19, 1907: a meeting held at the residence of J.W. White to organize the Standard Giants Base Ball club as reported in the February 22, 1907, edition of the Nashville Globe:

A significant event in Nashville’s Black community took place on Tuesday, February 19, 1907: a meeting held at the residence of J.W. White to organize the Standard Giants Base Ball club as reported in the February 22, 1907, edition of the Nashville Globe:

“Manager White called the house to order, and Mr. C.B. Reaves was made President: Mr. J.W. White, Manager, and W.G. Sublett, Secretary, and by unanimous voice of the house Mr. Howard Petway (brother of fellow Negro League player Bruce Petway), who did stunts for one of the professional teams of Chicago last season, was elected captain.“The Standards will travel extensively, having arranged games with Memphis, Hot Springs, Little Rock … playing all the leading teams, Chattanooga, Atlanta, Birmingham, Macon, New Orleans, and Beaumont, Texas. … One peculiarity is that every member claims Nashville as his home. It is composed exclusively of home talent, a characteristic no other team can boast of, and it is certain that every member will put up a fight for the glory of his home.”1

The Standard Giants joined local teams in the Capital City League, which became the premier league for Nashville’s African American teams playing their games at Greenwood Park and Athletic Park, later to become Sulphur Dell. The Black Sox, Nationals, Baptist Hill Swifts, Athletics, and Eclipse teams became established, and when others joined them, the community supported them all.2

One of those teams was the Maroons, and a young man named Thomas T. Wilson grew to love the game of baseball. Wilson, a native of Atlanta, had moved with his family to Nashville, where his parents, Thomas and Carrie, both physicians, studied medicine at Meharry Medical College. Wilson, born on November 29, 1889,3 played on the sandlots of Nashville with the Maroons4 as early as 1909, when he acquired the nickname Smiling Tom.5

Even though his highest school grade completed was the sixth grade6 in elementary school, Wilson began accumulating wealth through his interests in entertainment. He soon became an entrepreneur, owning a local rail line, a nightclub, and an illegal numbers lottery. Notwithstanding his reputation in racketeering, the admiration afforded him by teammates, players, and business leaders was strong.

Author Harriet Kimbro-Hamilton, daughter of one of Wilson’s brightest stars with the Elite Giants, Henry Kimbro, offered her view on why almost everyone admired Wilson for his success. “Back in the day, Black men could not go to the bank in those days,” she says. “The numbers game allowed them to play the odds, borrow money when needed, and sometimes take home some cash. Daddy did not run a numbers business, but he admired Wilson’s success and became a successful entrepreneur with a strong business sense like Tom Wilson.”7

Wilson longed to own a professional baseball team, and on March 26, 1920, he and others formed a corporation with the State of Tennessee to set his acquisition of the Standard Giants in motion. The charter reads:

“Nashville Negro Baseball Association and Amusement Company, for the purpose of organizing base ball clubs and encouraging the art of playing the game of baseball according to high and honorable standards and of encouraging the establishment of a league of clubs in different section(s) of the state; and also of furnishing such amusements as usually accompanying base ball games and entertainments. Said corporation to be located in Nashville, Tennessee, and shall have an authorized capital stock of $5,000.00.”8

- Clay Moore, J.B. Boyd, Marshall Garrett, Walter Phillips, W.H. Pettis, J.L. Overton, and R.H. Tabor joined Wilson as investors. Garrett would become an essential cog in the new venture.

Wilson purchased the local semipro baseball club, the Standard Giants,9 called them the White Sox, and, with Garrett at the helm, entered his team in the newly formed Negro Southern League. A 19-year-old future star born in Nashville who began his professional career with the club was Norman “Turkey” Stearnes, who was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 2000.10

Seven teams made up the balance of the Negro Southern League, formed one month after the Negro National League formed: the Atlanta Black Crackers, Birmingham Black Barons, Jacksonville Stars, Knoxville Giants, Montgomery Grey Sox, New Orleans Caulfield Ads, and Pensacola Giants. Nashville finished the season 40-40.11

In 1921 Wilson changed the name of his club once again, giving them a name that would become synonymous with Negro Leagues baseball: Elite Giants. Nashville won the 1921 NSL pennant with a 72-46 record; but with erratic schedules over the next few years, it is difficult to pinpoint how Wilson’s team fared between 1926 and 1929. The Elite Giants appear to have remained a member of the NSL but also had an associate membership in the NNL.

On April 17, 1929, a property deed transfer was recorded in Davidson County for the sale of 5 3/4 acres of land in Nashville from the estate of W.S. Whiteman, a Confederate veteran who owned real estate in the area and had died in 1926, to Tom Wilson for $10,000.

The property bordered Brown’s Creek to the east, Factory Street to the north, the rail line of the Chattanooga, Nashville, and St. Louis Railway to the west, and south to a point ending at Culvert Street and Brown’s Creek. The car tracks of the Nashville Railway and Light Company ended at an alley near Factory Street.12 Many newspaper articles include the location as “at the end of the Radnor Car Line” or “Second Avenue, South.”13 It was a mile from the Tennessee State Fairgrounds.

Wilson built a ballpark on the site to hold 8,000 fans. It was one of two African American-owned professional ballparks, the other belonging to Gus Greenlee in Pittsburgh.

The 1930 Federal Census shows Wilson’s occupation as “Proprietor – Ballpark.” Wilson Park would not only host games but community events with no regard to race. Years later, Wilson demolished his ballpark and in its place built the Paradise Ballroom, which allowed him a lawful source of income to finance his ballclub.14

Wilson Park became the spring-training ground for the Elite Giants after Wilson moved his club to Columbus, to Washington, and then to Baltimore. When Sulphur Dell was too soggy for the Nashville Vols to practice and play, they often used the ballpark for preseason games. The Elite Giants often alternated home games between the two ballparks based on the out-of-town schedule of the Nashville Vols in the Southern Association.15

A local newspaper described the game to take place on the night of June 13, 1926, and emphasized that all fans – meaning both Blacks and Whites – would be welcome to view the marvel of night baseball. Wilson’s advertisements and broadside announcements usually included the phrase “Special seats are reserved for white people.”16

Wilson’s mission had been to own a team exclusively in the Negro National League, formed by Rube Foster in Kansas City in 1920. The Nashville owner bided his time in the Negro Southern League until the opportunity came for a spot in the NNL in 1930. It was in that season when Nashville’s Wilson Park was one of the earliest ballparks to employ the unique lighting system purchased by J.L. Wilkinson for his Kansas City Monarchs to play night games.17 The Monarchs played a two-night-game series in Nashville on May 14 and 15.18

Nashville was unsuccessful in the NNL in 1930, finishing last with a 26-55-1 record.19 The next season the Elites rejoined the NSL as the NNL collapsed in the midst of the Great Depression. With most teams from the North, Wilson learned it was expensive for his ballclub to travel from Nashville. He moved the team to Cleveland in 1931 after obtaining Satchel Paige from the cash-strapped Birmingham Black Barons and renamed it the Cubs, but returned to Nashville in midseason when attendance did not support the move. Paige left the ballclub to pitch for Cum Posey’s Homestead Grays.20

Wilson placed a team in the California Winter League beginning with the 1931 season, naming it the Philadelphia Royal Giants. He signed stars Paige and Stearnes, Mule Suttles, Cool Papa Bell, and Willie Wells, among others.

In his book The California Winter League, author William McNeil calls Wilson’s teams some of the best assembled, writing, “The 1934-35 Elite Giants, along with the 33-24 aggregation, may have been the greatest Negro League team ever to play in the California Winter League. It is impossible to differentiate between the two.”21

Once again the Elite Giants returned to the disorganized NSL in 1932, becoming a barnstorming team for the most part. Nashville won the second half of the split season in 1932, earning a spot in the championship series against the Chicago American Giants. The team featured Stearnes as its star player.

“In 1932 with Joe Hewitt as manager, the Elite Giants were second half champions and played Chicago American Giants in the World Series,” wrote Bill Plott in his book The Negro Southern League. “Postseason series would be a more accurate designation,” Plott wrote.22

The NNL was reorganized in 1933, influenced by the leadership of the league president, Pittsburgh Crawfords owner Gus Greenlee, and the Elite Giants rejoined the league for two seasons. Greenlee and Wilson organized the first East-West All-Star Game, played at Comiskey Park in Chicago before 19,568 fans.23

In 1934 Wilson was elected vice president of the league. He organized a best-of-three Negro League “North vs. South” all-star series at Sulphur Dell in Nashville in the fall of 1934.

The series opened with a doubleheader on October 7. The Monarchs’ Stearnes hit a home run in the 12th inning to provide a 2-1 win for the North All-Stars. They also won the second game, 8-1. The South lineup came from Birmingham, Memphis, Monroe, and New Orleans; Nashville, Kansas City, Pittsburgh, and House of David stars represented the North. Felton Snow, Sammy Hughes, Tommie Dukes, Jim Willis, and Andy Porter represented the Nashville Elite Giants.

At the end of the year, Wilson was disappointed in hometown support, and by April of 1935 he announced Detroit to be his team’s new home as long as there was a suitable field to play on. When plans for the move fell through, the Elites resumed the season with home games at Sulphur Dell before also playing at Columbus, Ohio, during the season.24

In 1936 Wilson moved his team to Washington, a city abandoned by the NNL when the Washington Black Senators failed to finish the season. He did not completely abandon his Nashville fans, organizing a team named the Black Vols to play in Nashville.25

In 1936 Wilson became treasurer of the NNL, returning as vice president in 1937. The league needed to be more solid in 1938, and there was division within its ranks.

SABR author Doron Goldman wrote that controversy pitted the Elite Giants, Philadelphia, and the Pittsburgh Crawfords against Newark, the New York Black Yankees, and the Homestead Grays.26

A three-member board consisting of Wilson, Greenlee, and Abe Manley was formed to overcome the rift, and they chose Cum Posey, owner-manager of the Homestead Grays, as league secretary-treasurer.

There were hopes that the NNL and the rival Negro American League (NAL), formed in 1937, would agree to a single commissioner. Wilson moved his franchise to Baltimore in 1938, a historic change that would give him the solid footing he wanted. Bugle Field, a mostly wooden 6,000-seat ballpark, became the home of the Elites.

Even before moving to Baltimore, Wilson needed someone to get the Black community behind his team. He hired Richard D. Powell to make it happen. Powell, a courier, a fight judge, and an employee of local bookies, talked about the Elite Giants to business leaders and community organizations. The team won the support of the sports editor of the Baltimore Afro-American, Leon Hardwick; Powell wrote articles promoting the Elite Giants and Hardwick published them.27

In 1939, their second season in Baltimore, the Elite Giants captured their first NNL championship, defeating the Homestead Grays in a playoff series three games to one with one tie. It was Felton Snow’s first season as Wilson’s manager. The ballclub received the Jacob Ruppert Trophy.28 It was presented by Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, the entertainer who was a part-owner of the New York Black Yankees.29

Before the 1940 Opening Day doubleheader at Oriole Park against the Philadelphia Stars, Wilson presented wristwatches to members of the 1939 team. Then the Elites won both games, 6-1 and 5-2.30

Wilson would often travel with his team, but he maintained his suburban Nashville residence until he died. After moving to Baltimore, the team continued to hold spring training in Nashville,31 and Wilson formed a minor-league team, the Cubs, to feed the Giants with players. On one occasion, on April 6, 1947, the Nashville Cubs beat their parent Elite Giants, 5-1, at Sulphur Dell. Local hero Clinton “Butch” McCord was the first baseman for the Cubs.32

Wilson’s presidency of the NNL was sometimes the subject of controversy. In 1940 there was turmoil between Effa Manley, owner of the Newark Eagles, along with her husband, Abe, and Posey. Effa wanted Wilson removed from office, but failed to achieve her goal.

Wilson turned to the entertainment business by demolishing his ballpark in 1940 to build the Paradise Ballroom and forming a new enterprise to encompass all his ventures.

On April 29, 1941, Wilson and his wife chartered a new corporation, Elite Giants Baseball Club, Incorporated, with the State of Tennessee, to run his new facility.33 The venue included a dance floor and often hosted basketball games and boxing matches, and appearances by jazz greats including Lena Horne, Lionel Hampton, Jimmy Lunceford, Sarah Vaughan, and Cab Calloway.34

Political connections of all colors often frequented in the nightclub and Wilson invited Whites to attend events on the balcony with seating for 1,000.35 In 1945, he resurrected the Black Vols as a member of the Negro Southern League.36 The Louisville Courier-Journal described them as “one of the best teams in the South.” In December of 1945, the Paradise Ballroom hosted the Negro Southern Baseball League meetings.37

Effa Manley continued to pursue a replacement for Wilson in 1942. She believed that the NNL was poorly run by Wilson, needing an “efficient Chairman” because “we have never played the same number of games, our admission prices are all different, our umpire situation is pitiful, our contracts are not anything.”38

Wilson helped maintain peace between the NNL and the Negro American League. A key issue through the World War II years was the possible raiding of Negro League players by Organized Baseball. Wilson and the NAL’s president, Dr. J.B. Martin, met with Commissioner Happy Chandler, National League President Ford Frick, and American League President Will Harridge on January 17, 1946. According to Doron Goldman, Chandler proposed that when the Negro Leagues were better organized, there was an opportunity to become a part of a system of Organized Baseball. Once that occurred, all leagues, even amateur baseball, would fall under the authority of Commissioner Chandler.39

In a meeting in New York on January 5, 1947, Wilson was ousted after eight years as president of the NNL. John H. Johnson, a pastor and police chaplain, was elected to succeed him. Wilson was “advised to give up the job by his personal physician for reasons of poor health.”40

Four months later, on May 15, 1947, Wilson died at his home in Nashville, survived by his wife, Bertha, his daughter, Christine Wilson Childs, and his son, Thomas T. Wilson Jr. (It was only a month after Jackie Robinson became the first Black player in a twentieth-century major-league game.)

The Paradise Ballroom continued to operate until it was sold to a private racing club in the 1950s.

There appears to be no record of Wilson’s will. However, Thomas Jr. died two years later on August 9, 1949, and his will gives insight into the property acquired by his father, as it directed that his grandmother, Dr. Carrie L. Wilson, receive his house and lot on Sigler Street in Nashville, a Cadillac and Mercury Sedan, and two pistols “formerly the property of my deceased father.”41 In addition, he bequeathed to her a diamond ring in a white gold mounting that was his father owned, along with a watch and a Chevrolet pickup truck.

Thomas Jr. left the house on the Paradise Amusement Hall property to his “dear friend” Hattie Coleman, while he left his six motorcycles to two friends. Another friend was to receive the younger Wilson’s Chevrolet truck, while all three were to share in the possession of all remaining guns and ammunition.

In 2003, with the assistance of Butch McCord, a Tennessee state historical marker was erected on the sidewalk near a Nashville public school, the Johnson School.42 With confusion about the location several blocks away, the inscription reads: Tom Wilson Park, 1929-1946.

Formerly located near this site was Tom Wilson Park. It opened in 1929 and was home to the Nashville Elite Giants baseball team of the Southern Negro League. Owned by Thomas T. Wilson, the facility was one of two African American-owned professional ballparks. Wilson Park also hosted spring training sessions for the Nashville Vols. a minor league team of the Southern Association. Spring training games brought such baseball greats as Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, and Roy Campanella to the park. In 1946, Tom Wilson resigned and discontinued all ball activities at Wilson Park.”43

The entrepreneurial spirit of Tom Wilson includes a legacy of owning land in the city of Nashville and an estate in the middle Tennessee countryside, a successful nightclub, successful leadership in the Negro Leagues, a baseball team in several cities, and recognition as “The Father of Negro Leagues ball in Nashville.”

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank the staff of Nashville Public Library/Metro Archives, Sarah Arntz, Kelley Sirko, Grace Hulme, and Ken Fieth, for their valuable assistance in locating public documents on Tom Wilson, and extends appreciation to Dr. Harriett Kimbro-Hamilton for reviewing and offering suggestions on this biography.

Much of Tom Wilson’s career as an executive comes from Doron Goldman’s article “1933-1962: The Business Meetings of Negro League Baseball,” published in From Rube to Robinson: SABR’s Best Articles on Black Baseball, https://sabr.org/journal/article/1933-1962-the-business-meetings-of-negro-league-baseball/, accessed November 18, 2023.

Photo credit: Tom Wilson, courtesy of Larry Lester.

Sources

In addition to the sources credited in the Notes, the author consulted Ancestry.com, Findagrave.com, Newspapers.com, and Seamheads.com for information about Wilson and his family, and the following:

Lanctot, Neil. Negro League Baseball: The Rise and Ruin of a Black Institution (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004).

Wheeler, Lonnie. Cool Papa Bell (New York: Abrams Press, 2020).

Notes

1 “The Standard Giants Base Ball Club Royally Entertained,” Nashville Globe, February 22, 1907: 8.

2 “Capital City Baseball League Organized,” Nashville Globe, May 2, 1913: 1.

3 Wilson’s date of birth has been recorded as 1883, 1889, and 1890 in different places. However, his death certificate, signed by R.B. Jackson, shows his birth year as 1889.

4 James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 1994), 875.

5 Negro League Baseball eMuseum, https://nlbemuseum.com/history/players/wilsont.html, accessed September 24, 2023.

6 1940 United States Federal Census.

7 Dr. Harriett Kimbro-Hamilton conversation with author, January 24, 2024.

8 Nashville Public Library/Metro Archives Special Collections/ Davidson County Charters of Incorporation.

9 Negro League Baseball eMuseum.

10 William J. Plott, The Negro Southern League: A Baseball History, 1920-1951 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2015), 21.

11 Plott, 9-10.

12 City of Nashville Deed Book 735: 545-546.

13 See, for instance, “Black Cats Arrive Today for 3 Games,” Nashville Tennessean, July 29, 1929: 13.

14 Riley, 875.

15 “Elite Giants to Play Chicago Americans in Double-Header Today,” Nashville Tennessean, June 24, 1934: 11.

16 “Nashville Elite Giants Lose to Black Barons,” Nashville Tennessean, June 13, 1926: 10.

17 J.L. Wilkinson biography, National Baseball Hall of Fame, https://baseballhall.org/hall-of-famers/wilkinson-jl, accessed December 12, 2023.

18 “Elite Giants Bow to Monarchs in Second Night Tilt,” Nashville Tennessean, May 16, 1930: 19.

19 https://www.seamheads.com/NegroLgs/year.php?yearID=1930.

20 Negro League Baseball eMuseum, accessed January 22, 2024.

21 William F. McNeil, The California Winter League (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2002), 70.

22 Skip Nipper, “Negro Leagues Are Part of Area’s Story,” Nashville Tennessean, April 13, 2015: C5.

23 Riley, 875.

24 “Colored Outfits Wrangle in Dell,” Nashville Banner, July 2, 1935: 12.

25 “Black Vols,” Nashville Banner, April 24, 1936: 11.

26 “1933-1962: The Business Meetings of Negro League Baseball,” in John Graf, ed., From Rube to Robinson: SABR’s Best Articles on Black Baseball (Phoenix: SABR, 2021).

27 Bob Luke, The Baltimore Elite Giants (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009), 23-24.

28 “Final Double Header of Season at Yankee Stadium Sunday,” New York Age, September 23, 1939: 8.

29 Luke, 50.

30 “Elites Sweep Opening Series,” Baltimore Afro-American, May 18, 1940: 20.

31 Luke, 39.

32 Clinton “Butch” McCord interview with author, June 12, 2009.

33 Nashville Public Library/Metro Archives Special Collections/ Davidson County Charters of Incorporation.

34 Richard Schweid, “Club Built Among All Odds,” Nashville Tennessean, September 2, 1987: 19.

35 Paradise Ballroom Advertisement, Nashville Banner, May 15, 1941: 15.

36 Plott, 145.

37 “Negro Southern Drops 4 Cities,” Nashville Tennessean, December 7, 1945: 46.

38 Letter, Effa Manley to Rufus “Sonnyman” Jackson, January 2, 1942; letter, Effa Manley to Joseph Rainey, January 26, 1942, Manley Papers, Charles F. Cummings New Jersey Information Center, Newark Public Library, https://newarkpubliclibrary.libraryhost.com/repositories/3/resources/82, accessed February 5, 2024.

39 Doron Goldman, “1933-1962: The Business Meetings of Negro League Baseball,” https://sabr.org/journal/article/1933-1962-the-business-meetings-of-negro-league-baseball, accessed January 3, 2024.

40 Goldman.

41 Nashville Public Library/Metro Archives Special Collections/Davidson County Wills & Probates.

42 McCord interview.

43 The Historical Marker Database, https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=147542, accessed December 12, 2023

Full Name

Thomas T. Wilson

Born

November 29, 1889 at Atlanta, GA (US)

Died

May 15, 1947 at Nashville, TN (US)

Stats

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.