Chicago Cubs team ownership history, 1876-1919

This article was written by Michael Haupert

This article was published in the Team Ownership History Project

This article is part 1 of a planned multi-part series on the history of the Chicago Cubs franchise. This chapter covers the journey from the White Stockings to the Cubs from 1876 to 1919.

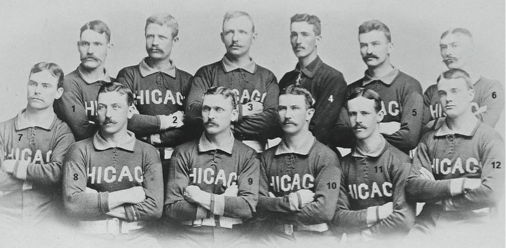

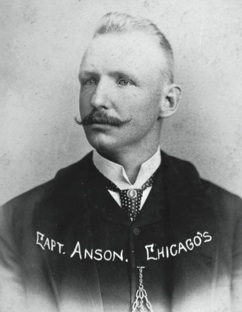

The 1885 National League champion Chicago White Stockings. 1-George Gore, 2-Silver Flint, 3-Cap Anson, 4-Sy Sutcliffe, 5-Mike Kelly, 6-Fred Pfeffer, 7-Larry Corcoran, 8-Ned Williamson, 9-Abner Dalrymple, 10-Tom Burns, 11-John Clarkson, 12-Billy Sunday. (Photo: SCP Auctions/David Kohler)

Birth of the White Stockings

The success of the 1869 Cincinnati Red Stockings, the first openly, all-professional baseball nine, sparked imitators. One of them was in Chicago, where jealousy and a fit of civic pride spurred prominent citizens to start a subscription that very summer. While Chicago had grown in size, it did not grow in stature, at least from the viewpoint of the business community. Despite its standing as the fifth largest city in America, the business community had an inferiority complex, and felt that Eastern cities did not take it seriously. The Chicago business elite were anxious to change that, and a group of them decided that baseball was the avenue that would lead to that change.

Word went out that on October 1, 1869, there would be a meeting of all those “interested in securing to this city a base ball club which shall beat the world.”1 Some 50 of Chicago’s elite businessmen attended a meeting at the Briggs House that night for the purpose of forming a professional ballclub. Among those in attendance were Potter Palmer (hotel and real estate tycoon), who was elected president of the newly formed Chicago Base Ball Club, and David A. Gage (once and future city treasurer), who was elected treasurer. The plan as proposed “would be not to form a stock corporation, but instead to keep a record of subscriptions, and at the close of the season declare dividends, if any, pro rata.”2

By the end of the month the new club was searching for players. An ad was placed in the New York Clipper headlined “To Base Ball Players.” It read, in part: “All professionals desirous of connecting themselves with the Chicago Club are requested to address, stating terms as to salary, etc. … [A]s evidence of the soundness and reliability of the movement, it is only necessary to state that Potter Palmer is President and David A. Gage Treasurer of the new club.”3 Before the season began, Palmer stepped down as president, and Gage was elected in his place.

The first player signed by the new club was Jimmy Wood. By Opening Day of the 1870 season, the roster was filled, and players were outfitted in handsome new uniforms sporting white stockings, which would quickly become the moniker by which they became famous. The Chicago Tribune noted that “the snowy purity of the hose has suggested the name of ‘White Stockings.’”4 That first season the White Stockings claimed three locations spread around the city as their home turf, rotating between Dexter Park, Ogden Park, and Lake Front Park.5

The White Stockings achieved other firsts that year, including the ignominious distinction of being the first professional team to be shut out. In response, sportswriters coined the term “Chicagoed” to refer to such an outcome.6 The whitewashing was symptomatic of bigger problems for the local nine. The Chicago Republican called for an overhaul of the club from top to bottom, citing its “miserably poor record,” which it blamed on both the players and management, accusing the latter of inefficiency, and calling for “the immediate reorganization of the club, for the next season, under some vigorous management.”7

The Chicago Tribune noted the discontent, reporting that shareholders realized that while professional baseball was a business, it was not the same as running a store or a hotel. The shareholders finally put their frustrations into action. On August 8 they ousted President Gage and replaced him with majority shareholder Norman T. Gassette. The move paid quick dividends. “When the White Stockings were at their lowest ebb, scarcely superior to one of our amateur nines, Norman T. Gassette was called to the presidency, and, by unremitting exertion, and rare administrative ability, in a few short weeks, placed the club on its old footing. … [T]he disorganizing elements have been weeded out and replaced by capable and willing hands.”8

The highlight of the White Stockings’ first season came in early September when they traveled to Cincinnati and vanquished the Red Stockings by a score of 10-6. “The mission of the White Stockings has been accomplished,” crowed the Chicago Tribune under a headline bragging, “The Redoubtable Red Stockings Defeated by Chicago’s $18,000 Nine.” Acknowledging that it was an expensive undertaking, the Tribune rationalized it by noting that “the organization was effected with a direct view to beating the Red Stockings, and they have done it.”9 So giddy were Chicago fans over this triumph that some 3,000 gathered at Union Depot to greet their conquering heroes when they returned late the next evening. Proving it was no fluke, the White Stockings put an exclamation point on their season with a second victory over the Red Stockings in Chicago the following month.

Despite the success and ensuing enthusiasm, the Chicago Tribune encouraged the team to close up shop. “The Chicago Base Ball Club … was organized to take the honors from the Cincinnati boys … and accomplished it. It has beaten the Red Stocking [sic], and all the other clubs, and now stands at the head of the game. This is the best of all times to disband … the misfortune of greatness is, that it does not know the proper time to quit. The inglorious disbandment of the Red Stockings [who had disbanded the previous day] should admonish the White Stockings to avoid a demise under similar circumstances a year hence.”10

Unfortunately for Chicago, like Cincinnati the year before, success on the field did not translate to the front office. The White Stockings ended the season $3,000 in the red, half of which was player salaries in arrears. But the Chicago Tribune reported in November that “the stockholders have lost neither faith nor enthusiasm, and it need surprise no one, if, after the 1st of January, they announce a nine which will challenge comparison with any in the land.”11

The season was neither a financial success nor an orderly affair. It ended in chaos, predictable given the method of recognizing the champion of the unorganized competition that existed in 1870. The whip pennant, the symbol of the baseball championship, was awarded to the best team over the course of the season. The pennant was not awarded to the team with the most wins or the best overall record, but had to be won from its current holder in a best-of-three match. The Mutuals of New York laid claim to the honor on September 22 with their second triumph of the season over the Brooklyn Atlantics, the holders of the pennant at the time.

One month later, the White Stockings were in a position to steal the pennant when the Mutuals visited Chicago. If they could defeat the New York club – having beaten them in New York earlier, they could lay claim to the pennant. The Mutuals traveled to Chicago on October 30 for the match, which ended in a controversy, called in favor of the White Stockings. Chicago thus laid claim to the pennant. Citing the controversial ending of the game, and claiming that it was after all only an exhibition, and not a part of the championship season, the Mutuals refused to relinquish it. Adding to the confusion, the Red Stockings had lost fewer games than any other team, but had lost twice each to both Brooklyn and Chicago. So, while technically not able to claim the pennant, they did have grounds to argue they were the best team over the course of the season. And they were not alone in clubs claiming for one reason or another to be the rightful champions. This sort of confusion, born of a loose agreement between clubs, would play a part in the formation the next season of the National Association of Base Ball Players, the first formal organization of professional teams, of which the White Stockings were a charter member.

The National Association

Norman Theodore Gassette, majority owner and president of the first National Association Chicago franchise, was born in Townsend, Vermont, on April 21, 1839. His family moved to Chicago when he was 10. He served as a brevet lieutenant colonel in the Union Army in the Civil War, was clerk of the circuit court of Cook County from 1868 to 1872, and became a prominent lawyer and realtor in the city. He died in Chicago on March 26, 1891, a month shy of his 52nd birthday. While his interest in the club waned after the devastating fire in October of 1871, he did chair the meeting held the next year to revive the team.12 By the time it returned to the National Association in 1874, he had moved on to other endeavors, selling his shares in the team to William Hulbert in the fall of 1876.13 He was one of a number of prominent businessmen to invest in the resurrected franchise. Others included Potter Palmer and David A. Gage, as well as General Philip H. Sheridan, George M. Pullman, the industrialist and inventor, J.M. Richards, president of the Chicago Board of Trade, and Francis B. Wilkie, editor of the Chicago Times, as well as an up-and-coming businessman by the name of William Ambrose Hulbert.

Hulbert would go on to become the president of the White Stockings as well as the second president of the National League. Before baseball, he was a successful businessman. He was born on October 23, 1832, in Burlington Flats, New York, a country crossroads 15 miles west of Cooperstown. His family (he had two brothers) moved to Chicago in 1836. He briefly attended Beloit College, but his primary education was on-the-job training. He worked for his father’s grocery business and for a local coal merchant before establishing his own grain trading offices and obtaining a seat on the Chicago Board of Trade.14

The National Association of Professional Base Ball Players was formally created at a March 17, 1871, meeting of 10 club representatives (the White Stockings among them) in New York City at Collier’s Rooms, a saloon on the corner of 13th Street and Broadway. The main purpose of the meeting was to bring order to the process of recognizing a champion among the professional base ball clubs in the country. Rules were discussed and a $10 entry fee was established for any team wishing to be considered for the championship pennant. There would be no set schedule. Each participating team was required to schedule a best-of-five series with every other participating nine. Teams were on their own to negotiate the time and place of such contests. The team with the most victories at season’s end would be awarded the championship pennant.

Much of Chicago’s 1871 roster was holdovers from the 1870 squad. Many of the players were from New York, and had been hired for their skill, not their ties to the Windy City, a fact that did not escape the notice of the New York Times, which referred to them as “the Chicago branch of the old Eckford Club.”15 Professional baseball was still a long way from a respected pastime in the eyes of many. In the minds of certain Chicago businessmen, however, it was a potentially lucrative investment.

The White Stockings abandoned Dexter Park for the 1871 season, citing the long commute as a detriment to attendance. Situated approximately six miles south of downtown Chicago, it was a solid 30-minute railroad ride and an hour by horse cart. In March of 1871 the city leased a section of Lake Park to the team for the construction of a new ballpark at Michigan and Randolph (the present-day Millennium Park) on the site of the Union Base-Ball Grounds at which they had played some of their games the previous year. It was referred to variously as Lake Front Park, White Stocking Grounds, and Lake Shore Park. Whatever the name, it was much easier to reach for the average Chicagoan. The Chicago Tribune reported that when completed, the park would have seating for 7,000 and that a full season ticket would go for $15. The White Stockings estimated the cost of the park at $5,000. The city set an annual lease of $200, despite some protestation. At least one alderman objected, presciently, that the city had no right to lease the land, since it belonged to the federal government. (The land was the site of the original Fort Chicago.) In addition, several businessmen who owned buildings on Michigan or Randolph objected. However, all concerns were overcome, the land was leased, and the ballpark built.16

By the end of September, Chicago’s first season of professional league ball could be considered a qualified success. The season was winding down and the White Stockings shared first place with Philadelphia, both sporting 18-7 records. In less than two weeks, Chicago would be embarking on its final Eastern swing, which included the fifth game of its series with Philadelphia, the teams having split the first four games. The fate of the team and, indeed that of the entire city of Chicago, were both about to take a drastic turn.

On October 8, 1871, the great Chicago fire began, and before it was over, 3.3 square miles of the city center were wiped out. An estimated 300 lives were lost along with 17,000 structures, leaving 150,000 homeless, including the ballclub and most of its players. The White Stockings lost their headquarters, equipment, uniforms, and ballpark, rendering them orphans for the remainder of the season, and ultimately leading to their exit from the league until 1874.

They gamely finished their Eastern tour, accepting free railroad passes and secondhand equipment and uniforms donated by opposing teams. “Not two of the nine were dressed alike. … [O]ne man wore a Mutual shirt and Eckford hose; another an Atlantic shirt, Mutual pants, and Flyaway hose, and so on; each man being obliged to borrow a shirt from anyone who was willing to lend.”17

Before the fire derailed their future, the White Stockings had already signed players for 1872.18 It was common in the early years of professional baseball for teams to sign players for the following season while they were still under contract, even with other teams. Clearly this was problematic, and would be one of the causes of the league’s eventual demise. At the conclusion of the season, Chicago released all players from their contracts, placing an announcement in the New York Clipper advertising their availability for the 1872 season.

Shortly after the conclusion of the season, the Chicago Base Ball Club canceled and surrendered its stocks. A committee was created to wrap up the details and close up the business. On November 12, less than a month after the fire, team secretary J.M. Thacher reported that some $1,500 had been disbursed in the past three weeks, most of it toward player salaries. Although the catastrophe had destroyed all of the club’s records and account books, Thacher reported that there was still $2,000 in the team’s bank account, which the stockholders later voted to divide evenly among the players. The ability to turn a profit under such dire circumstances was a glint of hope for the future of baseball, though the Tribune opined that “1872 will be a season of work in Chicago – hard, unceasing work for everybody, and we shall have little time to devote to an amusement. … Base ball is a luxury which we can dispense with for at least one year, and there should be no further steps toward the reorganization of the White Stocking nine.”19

Despite the fire and the Tribune editorial, baseball did not go away. On April 24, 1872, the Phoenix Base Ball Association was capitalized at $10,000 in shares of $100 each. A week later, the name was changed to the Chicago Base Ball Association. Among its 75 stockholders were several holdovers from the original franchise.20 The shares were widely distributed, with the majority stockholder, George Gage, owning only 10.21 The purpose of the association was to secure land in order to build a baseball ground, which it planned to lease to local amateur teams and visiting professional squads. An agreement was struck with a local businessman, Mr. Muhlke, to lease land on the south side, on Clark Street between 22nd and 23rd near the State Street car lines for $1,650 cash. The area was the location of the old Excelsior Grounds. It was estimated that construction of the grounds would cost $1,800 to $2,300. The grounds would seat 4,000 with room for another 1,000 standing. The new facility included a quarter-mile track and dressing rooms for the Chicago Athletic Club and visiting baseball players. The grounds were scheduled to be officially opened on May 25 with a series of sporting events hosted by the Chicago Athletic Club.22 The Chicago Base Ball Association was officially in business, even if the return of the White Stockings was still two years away. The Association lost $110 that year on revenues of $7,750, ending the year with $390 in the bank and assets valued at $4,890.23 All in all, a successful year for a base ball association that did not field a team.

On June 6, 1872, George W. Gage was elected president of the Chicago Base Ball Association, a position he would hold until his death three years later. The move returned direction of the team to its origins. Gage was the older brother of the team’s first president, David Gage. George Gage was born in Pelham, New Hampshire, on March 3, 1812, and made his fortune in the hotel business in Massachusetts before moving to Chicago in 1853, where he quickly established himself among the city’s business elite. He was the Republican nominee for mayor in 1869, and served as the city park commissioner for a number of years. Chicago honored his service by dedicating Gage Park on the city’s southwest side after his death on September 24, 1875.24

The plan to generate income through a ballpark was working. At the end of 1873, the Association had a cash balance in excess of $8,500.25 The funds were used to refurbish the park in preparation for the return of the White Stockings. The refurbished park sat nearly 7,000, and included 1,388 grandstand seats “furnished with comfortable settees … complimentary stand for the stockholders and other persons on the free-list.”26 A new side-track was constructed, connecting State Street to the entrance of the grounds, so that spectators could ride directly to the gates.

After a two-year absence, the White Stockings returned to the field in 1874. The 1874 Chicago White Stockings bore a strong resemblance to the 1873 Philadelphia White Stockings, Chicago having signed away seven of their players. Between 5,000 and 6,000 loyal fans turned out on May 13 to welcome the White Stockings back for their first home game in 2½ years. They were rewarded with a 4-0 “Chicagoing” of the visiting Athletics.27

Chicago’s return to professional baseball was underwhelming on the field. They finished the season with a losing record and a fifth-place finish, but did close the books with a positive balance. After spending $2,089 improving the grounds and paying nearly $18,000 in player salaries, the team turned a profit of $1,168 for the season. Revenue ranged from $5 in ice cream sales and $415 from rental of the grounds to a healthy $31,892 in gate receipts, one-third of which was paid out to visitors. The White Stockings were popular enough on the road to net $1,583.74 from their travels despite a financially disastrous early-season trip to Keokuk that earned them a paltry $56.28 The strength of their road performances came from their Boston trip in June, when the team took home over $5,600 from a three-game set.29 This rosy outlook would not last. The National Association was doomed, and the architect of its demise was rapidly rising in stature within the hierarchy of the White Stockings.

The future of the front office began to take shape that season when William Hulbert was elected secretary in August. Very quickly he made his presence felt, and began to take on a broader variety of tasks, including marketing, negotiating player contracts, and representing the team at the annual league meeting, where he was named to the rules committee. The Chicago Tribune, in announcing that Hulbert would represent the team, foreshadowed events under his leadership when it commented that he held “some very pronounced ideas on the punishment which should be meted out to ‘revolvers,’ and will make an excellent representative generally.” While attending the league meeting, he “saw that a radical reform should be effected, and an entirely new departure made, to place the national game on an enduring footing. The idea of a National League originated then and there … and before he left Philadelphia he had thought out the general plan.”30

The 1875 season witnessed several firsts for the White Stockings: 1-0 game (vs. St. Louis), no-hitter (vs. Philadelphia), and scoreless game at the end of nine innings (vs. Hartford).31 Unfortunately for the White Stockings, position in the standings was not included in that list. They suffered another losing season and finished sixth in an unwieldy 13-team league. The highlights of the season did not take place on the field. Rather, the excitement was in the front office, where dramatic changes were being made for 1876, when Chicago would debut a much-improved team in an entirely new league, all at the hands of William Ambrose Hulbert, who was promoted to team president after the death of George Gage in September of 1875.

The reconstruction process began much earlier. At the July 3 board meeting, Hulbert read a letter from Albert Spalding, who at the time was in the midst of another dominant season for the Boston Red Stockings. Spalding was offering his services as “manager” of the Chicago club for 1876. The board acted quickly, appointing Hulbert to go to Boston to pursue the deal with Spalding and to engage any other players for 1876 that he and Spalding desired.32

Two weeks later Hulbert reported back to the board that his trip to Boston was a rousing success. Not only had he secured the services of Spalding, but also his teammates Ross Barnes, Cal McVey, and Deacon White, as well as Ezra Sutton and Adrian Anson, currently of the Athletics. Spalding agreed to a guaranteed salary of $2,000 plus 25 of net profits. These were the terms of the contract reported publicly. However, the board approved a secret contract, which actually gave Spalding 30 percent of the net profits. Furthermore, Spalding would be elected “manager” of the team, and “was to have charge of and conduct in his own person, all the detail business of the association – the supervision of the Directory to be general.”33

The team had also promised Barnes a $2,000 salary and 25 percent of the net profits. McVey was signed for $2,000, White got $2,400 plus a promise of another $100 “if the club proves financially successful.” Anson was to receive $2,000, of which $200 was paid in advance. Sutton agreed to $2,000 plus $400 up front,34 though he ultimately reneged on the deal and stayed in Philadelphia. Anson also tried to back out of his deal, but in the end moved to Chicago, where he became the first member of the 3,000-hit club and became a Hall of Famer in 1939, along with Spalding.

The White Stockings were going all out for 1876 in more ways than one. For beginners, the signings flew directly in the face of what Hulbert had forcefully argued for earlier that year at the annual meeting of the National Association, when he advocated harsher punishments in an effort to stop in-season signings of players by one team from another. Secondly, the financial gamble was enormous. They had just signed six players to a total salary of $12,500. The White Stockings’ entire 1875 payroll for 18 players was less than $18,000, and those preliminary figures did not include the profit bonuses (which would ultimately cost the White Stockings $4,131). But most importantly, Hulbert was not concerned about his hypocritical behavior because he knew something nobody else did: There was not going to be a next year for the National Association. He was already formulating his plan to scuttle the league and create a new one.

President William Hulbert had purchased a single share of stock in the team in 1870 and thereafter steadily rose in prominence within the organization. He joined the White Stockings board of directors in 1872, was appointed team secretary in 1874, and president in 1875. He was now on the cusp of creating an entirely new league, of which he would also become president. Both the new team and league were created with the same cunning business acumen, amid secrecy that led to his desired outcome, and likely the best outcome for baseball and the Chicago franchise in the long run. But both reorganizations sparked outrage by those left behind, cut out of what would prove to be very profitable ventures.

At the same meeting at which Hulbert was promoted to the presidency, Albert Spalding joined the front office. He was elected to the board of directors to replace George Gage and appointed to succeed Hulbert as secretary, in addition to his previously assigned managerial duties.35 Unbeknownst to anyone at the time, Spalding’s remarkable playing career in Chicago was soon to be overshadowed by his front office role.

Albert Goodwill Spalding was born in Byron, Illinois, on September 2, 1850, to James Lawrence and Harriet Irene (Goodwill) Spalding. At the age of eight, Spalding lost his father. His mother then moved the family to nearby Rockford in 1863, where Spalding graduated from high school and enrolled in a local business college. Like his mentor, William Hulbert, Spalding began his career in the grocery business, taking a job as a clerk in Rockford. Unlike Hulbert, Spalding was a talented ballplayer, and joined the local Forest City nine as a pitcher.36

Harriet Spalding was well off, having inherited a good sum of money, so Albert was raised in a comfortable though not extravagant lifestyle. As was common for the time period, his mother was not happy with his interest in baseball and counseled him to pursue business, which he eventually did, to great success. But first he decided to give baseball a shot – another endeavor at which he experienced great success. He signed his first professional contract with the Excelsiors of Chicago in September of 1867 for $40 per week. He went on to a Hall of Fame playing career with Boston and Chicago, retiring while still in his prime to begin building his sporting-goods empire, which exists to this day.

Word began circulating that fall that the National Association was considering expelling the players Chicago had signed away from Boston and Philadelphia. Hulbert, however, was one step ahead of the league. After only five years in operation, the National Association was in trouble. It was weak and unable to control the player jumping, rowdy behavior, and gambling. Attendance declined each year of the league’s existence.37 As a businessman, Hulbert recognized an opportunity for profit and the shortcomings of the current structure in attaining that profit. The time was ripe for a stronger, centrally governed league.

Hulbert convened secret meetings during the winter of 1875-76, to which he invited representatives of seven clubs to join his Chicago franchise in the formation of an exclusive new league. He appealed to the owners, businessmen all, by using some simple economic logic. If businessmen ran the teams and players played ball, each party could concentrate on doing what they did best and everyone would be better off. The geographic exclusivity he promised to each club appealed to the owners as well. Exclusivity meant monopoly, and monopoly meant profit. The meetings concluded with the eight clubs abandoning the National Association and forming the National League of Professional Base Ball Clubs.38

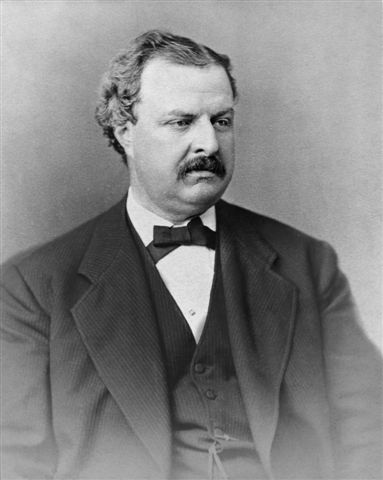

William Hulbert served as president of the National League in its inaugural season in 1876. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

The National League

In preparation for the 1876 season, Hulbert obtained an upscale clubhouse for his team on the southeast corner of Wabash and 23rd, just a block from the 23rd Street Grounds where the team would play the next two seasons. The White Stockings opened their 1876 home season on May 10 with a 6-0 blanking of the Cincinnati Red Stockings in front of 5,000 to 6,000 people who stood in line and had to “go through all sorts of troubles to get tickets and seats for Chicago’s opening game.” The Chicago Tribune boasted the following morning that “it looks as if the Chicago club management had done it at last – had selected a club to fitly represent this city, and therefore to excel all other clubs in the West, if not in the country.”39

The season was a success on a number of fronts. The White Stockings won the pennant, the first of six they would capture in the first 11 years of the league’s existence, and turned a profit. The league itself survived, and would weather major scandals in its early years to validate Hulbert’s foresight. He was a visionary, a master of organization and persuasion, and a stealthy operator. Under his leadership the White Stockings and the National League both thrived, and continued to do so long after his premature death. And he wasn’t done. Perhaps the biggest success of the season was his reorganization of the team charter – another event that was accomplished largely in secrecy.

On July 30 the Chicago Tribune addressed fan concerns regarding the White Stockings’ lack of activity in securing their players for the 1877 season: “Mr. Hulbert is doing just what is wisest under the circumstances; and, as he should be given the credit for assembling the only first-class team Chicago ever had, so he should be let alone in his movements for 1877. He will do just what is best, no doubt.”40 But best for whom, was the question that should have been asked.

There was a very good reason that no players had yet been signed for 1877. For on July 30, there was no White Stockings franchise. The team’s charter had quietly expired some months before, and was not legally allowed to conduct any business other than the dissolution of the now expired Chicago Base Ball Association. Unbeknownst to the Tribune, and also unbeknownst to some of his co-owners, Hulbert was hard at work creating a new organization, which would field a White Stockings team in 1877. This new charter would be leaner and more top-heavy in control, with Hulbert in charge.

In the summer of 1876, Hulbert reorganized the team, buying out the shares of the now defunct Chicago Base Ball Association from several stockholders, who by then numbered 59 and held 70 shares among them. The majority shareholder among these 59 was George Gage with five shares. Nobody else held more than three shares. Hulbert had one. Between July 24 and October 30 a total of 35 shares were transferred to Hulbert, leaving him with 36 of 70 shares now held by a total of 30 people. Thus, Hulbert held controlling interest of the expired association, and set about closing it down.

The newly created charter was called the Chicago Ball Club, which was capitalized on August 26th with 200 shares of stock at $100 each. Those 200 shares were initially subscribed by 32 people. William H. Murray (50); Albert Spalding and Ross Barnes, both active players on the White Stockings at the time (30 each); Hulbert (22); and J.B. Lyon (20) were the majority stockholders.41

About a dozen of the disenfranchised stockholders hired an attorney to fight for their ownership rights. The issue was resolved by Hulbert, who “was obviously just scuttling some individuals he considered undesirables.”42 While perhaps behaving unethically, Hulbert did nothing illegal in shutting out most of the previous association’s stockholders. They were paid their due and summarily uninvited to participate in the new venture. Literally, out with the old and in with the new – and some of the favored old. Seven of the stockholders who were left holding stock from the old corporation joined Hulbert in the new corporation. Six of them (including Hulbert) were original charter members from 1872.43

One cannot help but wonder if Hulbert, shrewd executive that he was, deliberately let the association’s charter lapse so that he could rid himself of meddlesome stockholders who did not share his vision for the White Stockings.44 The Chicago Tribune praised the reorganized club, saying it “contains within its small number of stockholders all the best elements of the support of the game in this city.”45

The National League debuted in 1876 with eight teams. It would enter the next season with six, after the expulsion of New York and Philadelphia during the league’s winter meetings. William Ambrose Hulbert added the title of league president to his résumé when he was elected to succeed the retiring Morgan Bulkeley in December. He would continue to preside over both the White Stockings and the National League until his death on April 10, 1882.

Under Hulbert’s steady hand, both the league and the White Stockings flourished. The league survived a hippodroming (intentionally throwing games) scandal, the expulsion of another franchise (Cincinnati in 1880), and a revolving cast of members.46 It instituted the reserve clause and fixed schedules, clamped down on gambling, and begat stability from the chaos of the National Association. In short, while not without its growing pains, it became everything that Hulbert predicted. And that was to the great benefit of the White Stockings, who finished every season of Hulbert’s presidency in the black, won four of the first seven league titles, built a new ballpark, and produced three of the league’s first five presidents.

On April 1, 1880, Adrian C. Anson purchased Edwin F. Dexter’s five shares, and on August 24 the White Stockings purchased the 30 shares held by Ross Barnes. Cap Anson’s ownership of stock in the Chicago club was credited as a powerful influence in keeping him from abdicating for the Players’ League a decade later.47 The result of the reshuffling meant that by the fall of 1880 the majority stockholders were William H. Murray (50 shares), Albert Spalding (30), Hulbert (26), and J.B. Lyon (20), who between them held 74 percent of the 170 shares outstanding.48

The magnates of the National League surely appreciated Hulbert for creating a profitable monopoly and allowing them to share in its riches. His players also appreciated him. During the final home game of the 1881 season the players presented Hulbert with a ‘“massive” gold watch chain and locket “as a token of their respect and esteem.” One side of the locket featured the initials ‘W.A.H.’ while “From the boys of ’80 and ’81” was inscribed on the other side. Inside the locket were small ovals for portraits of the 12 donors of the nearly $200 it cost for the memento.49

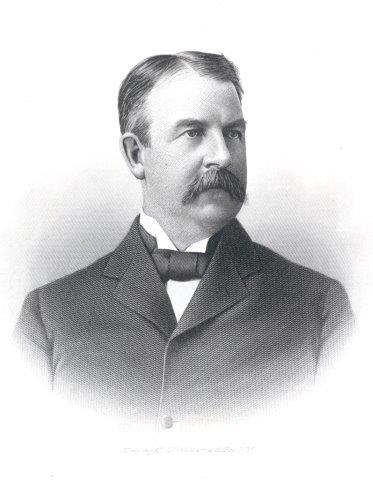

Albert Spalding, a great pitcher and an even greater entrepreneur, began serving as president of the Chicago White Stockings in 1882. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

From Hulbert to Spalding

William A. Hulbert died on April 10, 1882, after a long illness. The future of the team was never in doubt. Just two weeks after the funeral, Albert Goodwill Spalding was unanimously elected president of the White Stockings. His ascendency to the position corresponded with a consolidation of stock. On April 26 the board met and unanimously voted to purchase Hulbert’s stock at par value from his widow, though at the time of his death Hulbert had paid in only 40 percent of the par value. Spalding became one of the two principal owners, along with John L. Walsh, president of the Chicago National Bank.50 Spalding financed his additional shares from the considerable wealth accumulated in his sporting-goods business, which was on the verge of monopolizing the industry – in the following year he would buy out his chief competitor, Al Reach. He had already scored a coup when Hulbert named his company the official supplier of National League baseballs and the printer of the league’s annual guide.

Walsh was connected to the team through Spalding. He had been a benefactor of Spalding’s when he first opened his sporting-goods company. At the time, Walsh was president of the Western News company. When Spalding opened his first store in Chicago in February of 1876, Walsh bought 10,000 baseballs from him for the news company, placing Spalding’s business on firm ground.51

After a spectacular, though brief (seven-year) pitching career, Spalding retired after the 1877 season to attend to his burgeoning sporting-goods business. He continued to act as secretary of the team, a position he had assumed while still a player. Spalding was in name the secretary, in practice arguably the first general manager. He put together the roster that dominated the early years of the league, winning championships in 1876, 1880-82, and 1885-6.

Spalding displayed his business acumen in the way he ran his ballclub. He made it clear by his actions that baseball was a business, not a game – a distinction that has not always been appreciated. He was a marketing genius. In addition to winning valuable endorsements from organized baseball for his company, he also used the White Stockings to promote baseball and further promote Spalding Brothers Sporting Goods when he took players on a world tour during the winter of 1888-89.

Spalding also recognized opportunities to improve his team. He initiated the practice of spring training to get his players in peak condition for the beginning of the season, taking the club to Hot Springs, Arkansas, for the first time in 1886. He was also a pioneer when it came to employing scouts, in an attempt to keep the pipeline full of future players.52

He ran his club relentlessly, demanding the best from his employees. This was particularly evident in his approach to alcohol. Like Hulbert before him, Spalding was adamant about promoting player sobriety. He used his annual league Guide to rant against the evils of high salaries, home-run hitters, and alcohol, comparing the evils of drink to the throwing of games. “Temperance in the ranks during the summer championship season has become a necessity if only for financial reasons. … Players are paid excessive salaries for the labor they perform, and the man [with] … an unnatural appetite for intoxicating liquor, is as much a violation of his contract, as would be his conspiring to sell a game. … Thousands of dollars in loss of public patronage was one of the results of the past season’s mistake of the condoning of the offense of drunkenness in the ranks.”53

In order to enforce his convictions on temperance, Spalding employed detectives to trail his players to determine who among them was breaking their sobriety pledges. In the midst of the 1886 season, he leveled $25 fines on seven of his stars for “keeping too late hours and flirting with beverages not calculated to keep an athlete in good form.”54 Star outfielder Mike “King” Kelly’s propensity toward excessive drink eventually drove Spalding to dispose of his most popular player, selling him to Boston for the princely sum of $10,000 that winter.

By January 1882, Spalding had already re-signed the core of the 1881 champions for the new season. In March of that year, just weeks before Hulbert’s death, he signed an even bigger contract – this one with the National League and its new competitor, the American Association. Spalding secured an exclusive agreement with both leagues for his sporting-goods company to be the official provider of baseballs for all league games. The contract was a five-year deal, granting Spalding the option of renewing for an additional five years.55

The White Stockings won their third consecutive pennant in 1882. That December the National League elected Abraham G. Mills to succeed Hulbert as league president.56 Mills was a close associate of Spalding’s. The two had worked together in the White Stockings front office for six years. While he never held a major position on the club, Mills sometimes represented the team at NL meetings, and had worked closely with both men for several years. His election secured the strong connection between Chicago and the league office, which would extend into the twentieth century.

The White Stockings opened the 1883 season in a ballpark renovated to the tune of $10,000.57 Seating capacity was more than doubled to 10,000, with “comfortable” seating for 8,000, including 1,800 reserved seats. “The whole interior of the park has been remodeled, and there are certainly no grounds in America to equal them.”58 Harper’s crowed that they were “indisputably the finest in the world in respect of seating accommodations and conveniences.”59 Eighteen private boxes with privacy curtains, comfortable armchairs, and a telephone and gong for President Spalding were added on top of the grandstand for the use of club officers, reporters, and “those who may wish to pay the extra charge for occupying them. … Chicago has the champion club and now possesses the champion grounds.”60

The White Stockings played only two seasons in their newly remodeled park. After the 1884 season they were forced out by the city. In May of that year, the US government, owner of the property on which the Lake Front grounds were located, sued the city and team, alleging that the city violated the intended use of the grounds as open and public, and had no authority to allow its use for private or commercial purposes. US Circuit Court Judge Henry Blodgett ordered the city to desist from leasing the grounds and gave the team until November 1 to vacate them, at which time the city was instructed to clear all buildings and fences.61

The 1884 season was a tough one for the White Stockings. Their payroll was reportedly the highest in the National League, but their attendance plummeted more than 30 percent to 88,218, due to the competition from the rival Union Association franchise, located on the south side of town.

Spalding, determined to reverse the attendance slide, decided that a great ballpark was the way to go. The new ballpark, built at a cost of $25,000, was erected on the west side of the city, near three trolley lines, and easily accessible by “a larger population than the North and South Sides combined.” It was designed to be used for a variety of sports, including cricket, lacrosse, lawn-tennis, and bicycle racing, with a bicycle track built around the interior of the walls. The White Stockings signed a five-year lease on the lot, bounded by Congress, Harrison, Throop, and Loomis Streets. An enthusiastic Spalding announced that “no pains or expense will be spared to make these the finest base-ball and athletic grounds in America.” Sporting Life agreed, calling it “the finest and best in the world.” In lieu of an “unsightly board fence … a substantial, stone-capped brick wall twelve feet in height will be constructed, to extend entirely around the grounds.” Sunday games, alcohol, and gambling of all types were prohibited at the new ballpark (never mind that they were already prohibited by the National League) in an effort to curry “the encouragement and patronage of the better class of people.”62

The White Stockings christened the new ballpark on June 6, 1885. “The game played upon the new grounds of the Chicago Club between the St. Louis and home teams yesterday attracted one of the largest audiences ever assembled at a ballfield in this city, the turn-stiles showing the registry of 10,327 people,” noted the Tribune. “The grand-stand was packed, as were also the open stands, and in addition 500 chairs which President Spalding ordered sent to the ground were sold, and 2000 people stood upon the bicycle track upon each side of the diamond. … Every housetop and window commanding a view of the grounds was occupied by spectators, and at a rough estimate fully 2000 people must have witnessed the game in this way. The east end of the grounds was filled with carriages, and quite a number of vehicles for want of room were compelled to stand outside on Congress, Throop, and Loomis streets.”63 According to the White Stockings’ own attendance records however, the actual crowd that day was 6,477.64

There were reports of the White Stockings drawing crowds in excess of 10,000 on multiple dates during the season.65 However, team records indicate that the biggest crowd of the year was 7,752 for the morning game of a July 3 split doubleheader versus New York. The second game attracted 5,473. In total, attendance exceeded 5,000 only seven times in 58 home games for a season total of 119,318.66

The Chicago Daily News reported in early October that the White Stockings took in approximately $300,000 in revenue against expenses and salaries of $40,000.67 This is another example of reporting hyperbole. In order to earn this kind of revenue they would have had to draw an average of over 8,000 per game both at home and away. In fact, they averaged 2,057 per home game, and historically were a much better draw at home than anywhere on the road.68 Whatever the exact figure, the players benefited from the successful season. The 1885 postseason series between the NL champion White Stockings and the St. Louis Browns of the American Association ended in a tie. Players from both teams split the $1,000 prize pot, sponsored by the two teams. The postseason series was neither well attended nor followed, interest in baseball having faded at the conclusion of the regular season. White Stockings players were also promised cash bonuses for having honored the temperance pledges they signed in April before they left Chicago for spring training.69

In the midst of the postseason series, the two leagues met in New York City and inked a new national agreement that provided, among other things, that no player contracts would be written for a period to exceed seven months, no contracts would be made for the following season prior to October 20, and that for the first 10 days after his release, a player could only be signed by other teams in his original league. Only after this 10-day period could teams from the other league sign him. Each league promised to recognize the other’s reserve clause, with no team able to reserve more than 12 players. The agreement also provided geographic monopolies for all clubs in both leagues. The most important move, however, was the new salary cap. Immediately, it provided cost control for clubs by limiting salaries to a range of $1,000 to $2,000 per season and prohibiting advance payments except for train fare to join the club in the spring.70

Spalding showed his appreciation for a pennant-winning effort again in 1886. After the team clinched the title on October 9 in Boston, he sent a telegram congratulating them for having “clinched the pennant in great style. … Now come home and win the world’s championship. As a token of my appreciation of your work I herewith tender each man of the team a suit of clothes, and the team collectively one-half the receipts in the coming series with St. Louis. Accept my hearty congratulations.”71 Alas, the Browns won the series and with it the prize of the total gate receipts, as previously agreed upon by Spalding and Chris Von der Ahe, the St. Louis owner. There are no records indicating whether Spalding honored his pledge to award half the gate to his players.

Perhaps due to the disappointing series loss, Spalding’s appreciation for the pennant-winning White Stockings was fleeting, and he began to break up the team that winter. After the disappointing showing, he refused to pay temperance bonuses to several players, accusing them of backsliding on their promise, and hinting that drink played a part in the loss to St. Louis. In one of the most famous baseball transactions of the nineteenth century, Spalding shipped Mike Kelly to Boston for $10,000. He followed that by sending Jim McCormick to Pittsburgh for George Van Haltren and $2,000, and George Gore to the Giants for a reported $3,500. The next year he sold John Clarkson to Boston for another $10,000,72 ending the Chicago dynasty. It would be 20 years and several team nicknames before they would win another pennant.

The following spring, Spalding turned his attention to leaguewide matters, floating a plan to form a single major league from the AA and the NL. His plan called for eliminating Cleveland and the New York Metropolitans from the AA and Indianapolis and Washington from the NL, and combining the remaining teams into a single 12-team league. This plan went nowhere, but presaged the events of five years thence, when the collapse of the American Association resulted in four AA teams being absorbed into a new 12-team NL.

The NL made big news at its fall meeting in November of 1888. The league unilaterally decided to opt out of the maximum-salary schedule they had agreed to three years earlier and replace it with a classification system. The system was to take effect on December 15 and would exempt any contracts in place before that date. Thereafter, however, players were to be paid based on their classification. Owners would assign each player to a class, ranging from A to E, according to skill and off-field deportment. Salaries would range from $2,500 for Class A players down to $1,500 for those in Class E. All players in a given class would receive the same salary.73 The classification system helped spur the formation of the Players’ League in 1890.

A hot rumor floating around the meeting hotel was that a majority of the clubs favored the formation of a baseball trust. The purpose of the trust would be to provide financial assistance to the weaker clubs from the wealthier clubs.74 Details were not provided, but the basis of such a system was already in place, with some owners holding stock in more than one club. In 1890 John T. Brush owned the Cincinnati club and the minor-league Indianapolis club, as well as stock in the New York entry in the National League, which also counted as stockholders Arthur Soden (who held 33 percent of Boston’s stock), Spalding, and Ferdinand Abell, who also owned 40 percent of both the Brooklyn and Baltimore franchises. Harry Von der Horst also owned 40 percent shares of Brooklyn and Baltimore. Ned Hanlon and Charles Ebbets each held 10 percent of the stock in both Baltimore and Brooklyn. And Frank Robison owned the St. Louis (AA) and Cleveland (NL) franchises.75 It wasn’t the single-entity trust rumored two years earlier, but the interlocking interests of the franchises were enough to question the independence of any team. This sort of relationship was certainly characteristic of Spalding’s approach to base ball as a profit-maximizing business, no different than his approach to the sporting-goods industry.

The Players’ League

Spalding worked diligently behind the scenes to prevent an American Association team from locating in Chicago in 1890, using the press to spread propaganda about the inability of Chicago to support two professional teams.76 He was right. While he succeeded in fending off competition from the AA, he was not successful in monopolizing the market. That year saw the debut (and farewell) of the Players’ League, which placed franchises in seven NL and AA markets, including Chicago, with disastrous financial results. Attendance at the West Side Grounds plunged 31 percent to 102,536.77 The PL Pirates, who played across town from the White Stockings, drew 148,876. They were only one of six Players’ League teams that outdrew their NL and AA crosstown competitors.78 The attendance victories were short-lived, however. The increased competition from the upstart league resulted in the NL reportedly losing $231,000, with the White Stockings alone losing $35,000. The red ink extended to the Players’ League, which allegedly lost $125,000, with the Pirates responsible for $16,000 of that amount.79

The Players’ National League of Professional Base Ball Clubs (PL) had been organized over the previous winter by the Brotherhood of Professional Baseball Players, the first player union. Disenchanted by the salary classification system and reserve clause, players leapt at the opportunity to join a league in which they would be partial owners of the franchises for which they played. The PL attracted many of the game’s stars, and filled its rosters with players who had defected from the National League and American Association.

Spalding’s penurious reputation and his hard-driving, inflexible style, particularly when it came to alcohol, cost him dearly. When faced with the option of playing for Spalding or fleeing for a new league, the White Stockings players voted with their feet. Spalding lost 13 of the 19 players from his 1889 roster to the Players’ League, seven of whom moved south to 35th and Wentworth to play for the Pirates. In addition, three other players departed, leaving the White Stockings with only three returning players for the 1890 season. Spalding rebuilt his roster with younger players, leading sportswriters to refer to the team as the Colts.

As bad as things were in Chicago, they were no match for the crisis faced by the NL’s New York entry, which was nearly bankrupted by the competition. In a desperate attempt to rescue the franchise, Spalding organized a consortium of owners to back John T. Brush in his purchase of the team from John B. Day. Spalding and Soden (Boston) each matched Brush’s $20,000 investment, and the other $20,000 of the total $80,000 purchase price was put up by Reach (Philadelphia), Ferdinand Abell, and Charles Byrne (the latter two owned stock in the Brooklyn National League and New York American Association franchises).80

Spalding was elected by his peers to lead the NL’s “war committee” against the Players’ League. His primary weapon was to employ a divide-and-conquer strategy, pitting the Players’ League athletes against the financiers by offering the latter a chance to buy into the NL. But he also planned to fight in the courts, in the newspapers, and at the gate. In order to control the flow of information, Spalding took a page from his own playbook. He took control of the media by purchasing the Reach Baseball Guide and the New York Sporting Times. He hired O.P. Caylor to edit the sporting paper and used the publication as the NL’s mouthpiece.81

Spalding planned a scorched-earth approach to the battle, calculating that the NL owners could afford to lose more money in the short run than their PL counterparts would be willing to lose, declaring in March of 1890, “I want to fight until one of us drops dead.”82 The key to victory lay in the recognition that businessmen are in business to make profits and, when faced with the prospect of large losses or the possibility to buy into a profitable monopoly, the PL owners quickly chose the latter. The league, and hence competition, was vanquished, but its strengths, the monied men behind it, became part of the National League.

National League teams purchased and merged their PL competitors in Pittsburgh, New York, Brooklyn, and Chicago. Spalding bought out his competitor for $25,000.83 The purchase included the lease on their ballpark, known then as Brotherhood Park but eventually called South Side Park, which had a capacity of nearly 11,000 plus standing room for another 5,000. Streetcar lines provided convenient access to the park, located at 35th and Wentworth (the same intersection now occupied by Guaranteed Rate Field). But the White Stockings had a loyal following at West Side Park and feared fan outrage if they abandoned those Congress Street grounds. Their solution was to use both ballparks, scheduling half their home games at each in 1891. Brotherhood Park was leased for $1,500 per year, a far cry from the $7,500 the White Stockings were paying for West Side Park. In addition, the club was leasing a plot at the intersection of Lincoln (present day Wolcott) and Polk, just a few blocks from West Side Park, for $6,000.84

John Addison (for whom the street bordering the south side of Wrigley Field is named) was a prominent Chicago architect and the principal financial backer of the Chicago Players’ League franchise. As part of the settlement, he exchanged his shares of the Pirates with Spalding for shares in the White Stockings and New York Giants. The deal was not without some drama, however, as his co-owners threatened a lawsuit, temporarily holding up the exchange. In the end, Addison sold his shares, dividing $18,000 between nonplaying shareholders at 60 percent of par value, and the Pirates players, who received a settlement on their unpaid salary balances. In addition, the six players who held stock were paid off at 50 percent of par value.85 In the end, his involvement with the team was minimal, and his last known connection was when he built the second iteration of West Side Park in 1893 on the lot being leased by the club. It remained home to the team until the Cubs moved into Wrigley Field.86

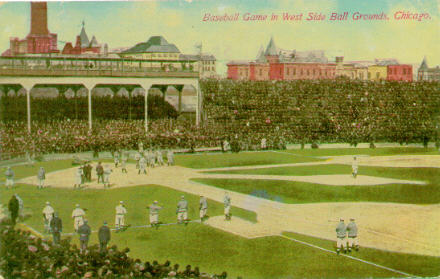

The second iteration of West Side Grounds opened in 1893 and was the Chicago Cubs’ home through the 1915 season. (DOUG PAPPAS COLLECTION)

A Change of Leadership

In April of 1891, after an exhausting offseason, Albert Spalding turned in his resignation as president of the club in order to devote more time to his sporting-goods business. He “washed his hands of the Chicago club’s affairs and turned the entire business over to James Hart, who was unanimously elected President of the club for the ensuing year.” Spalding explained that he had intended to retire upon returning from his world tour, but put it off due to the Brotherhood revolt. “Now that this matter has been settled and the National League reestablished on a good, firm basis, I feel that I can quietly retire from active base-ball management without being accused of deserting the old organization in time of adversity,” Spalding said. He retained stock in the ballclub, and expressed his confidence in Hart, “a man thoroughly competent and well qualified.”87

Hart had recently joined the White Stockings front office as club secretary. He had a history with Spalding, having managed the team of all-stars facing the White Stockings during the 1888-89 world tour as well as serving as the tour’s business manager. Hart was an experienced manager at the time and also had success touring baseball teams. His managerial career began with his college team, the Grand River Institute in Ohio, in 1874. For the next several years he managed a variety of amateur teams before purchasing stock in the Louisville franchise of the American Association, where he was named vice president in 1884. The next year he was named manager. He led his team on a postseason tour to the West Coast after the season and managed the team again in 1886. He sold his stock and left Louisville in the spring of 1887 when he bought the Western Association’s Milwaukee franchise, which he managed until he sold it after the 1888 season.88 During the winter of 1887-88, Hart took three National League teams, including the White Stockings, to California on tour and “through the most careful management prevented the scheme from being an utter failure.” Slight praise for a trip that was a financial success.89

Hart was born in Girard, Pennsylvania, on July 10, 1855. Prior to his baseball connections, Hart had been a successful businessman, owning retail stores in four states at various times. He also dabbled in the theater, as half-owner of a venue in Milwaukee. After working with Spalding on the world tour, he spent the 1889 season managing the Boston National League team, and then returned to England in 1890 to start the British Base Ball League, organized by Spalding. The league failed after one season, sending Hart back to the US, where he joined the White Stockings.90

Chicago’s decline in the standings paralleled the ascent of James Hart to the club presidency. The transition was not a smooth one. Anson was not happy to have been passed over for the presidency. Despite conciliatory words from Spalding, who assured him that Hart was merely a figurehead, the incident opened a rift between Spalding and Anson.91 Anson also had problems with Hart, and the two began to butt heads almost immediately. “Hart regarded Anson as a relic of the past who was unwilling to change with the times. Anson countered by calling Hart a usurper who undermined his authority by encouraging rebellion among the players.”92

Hart’s conflicts stretched beyond the White Stockings. He capped his first season as president by accusing New York of throwing its games against Boston late in 1891 in order to deny the pennant to the White Stockings. He claimed to have information that there had been “either downright dishonesty on the part of the New York club, or gross incompetency on the part of those in control of the team in the games played in Boston.”93 He insisted that the league investigate the matter. The Giants executive committee met with the players on October 8 and exonerated them of any wrongdoing. A few years later Hart went after one of his own, accusing pitcher Jack Taylor of throwing games to the crosstown White Sox in the postseason city series. In this case, it appeared that Hart was correct in his suspicions. Taylor was reported to have been overheard saying something like “Why should I have won? I got $100 from Hart for winning, and $500 for losing.” Things got worse for Taylor, who was hauled in front of the National Commission on charges of throwing games, and was fined, though he avoided any harsher penalties.94

Hart’s most dramatic confrontation came during league meetings in March of 1899, when he tangled with Philadelphia owner John Rogers. During a dispute about enforcing fines, Hart “tried to land a knock-out blow on Colonel John I. Rogers of Philadelphia, and Rogers in turn made an effort to draw his pistol.”95 Quick thinking by President Young, who jumped between the two would-be combatants, prevented any injuries beyond personal pride.

At the conclusion of the 1891 season, National League champion Boston refused to play the American Association champions from the same city. By the following spring, the AA folded and the NL absorbed four of its franchises.96 In so doing, the NL bowed to the popular 25-cent ticket, a hallmark of the American Association, directing all teams to dedicate a portion of their seats for the lower priced admissions. Ever the businessman, Spalding rejoiced at the elimination of another competing league, predicting lasting peace and prosperity. He firmly believed that profitability and contentment were a function of monopoly. Peace, if not prosperity, lasted the rest of the decade, before the National League finally met a foe it could not vanquish.

The dramatic decrease in the number of available jobs for ballplayers was quickly exploited by the National League, which cut salaries by as much as 40 percent for the 1892 season. Hart described the cuts as “only the natural consequences of baseball history,” asserting that “the same thing is done every day in other lines of business, only no talk is made of it.”97

Before the 1892 season, President Hart announced that the White Stockings would play all their games at the South Side Park, temporarily abandoning West Side Grounds.98 The move seemed practical for a number of reasons. The team had drawn more fans at the south side location in 1891, Hart was looking forward to the anticipated 1893 World’s Fair crowds spending their afternoons at the nearby South Side grounds, and the team was planning to build a new ballpark at a west side location, announcing that “it is probable that we will play there next year, as the West Side is the best part of the city for ball games.”99 Beginning in 1892 the NL allowed Sunday games, but the Colts’ lease at the south side grounds prohibited Sunday ball.

It was the potential profits of Sunday ball that eventually led to a major reorganization of the White Stockings franchise. President Hart believed in the future of playing on the Sabbath, but majority stockholders Spalding and Walsh were not interested in pursuing the opportunity. However, they were not against selling their shares to someone who was. So, in the fall of 1892 Hart, along with Charles M. Sherman, an attorney, and Thomas Barrett, a member of the Chicago Board of Trade, purchased the White Stockings.

The sale involved creating a new stock company, the Chicago League Ball Club, capitalized at $100,000. It took over the franchise and the lease on the south side grounds. The original stock company was still held by Spalding, Walsh, and Charles T. Trege.100 It no longer had any direct control over the team. Instead, the old corporation managed real estate. It owned a large parcel of property at Polk and Lincoln (later Wolcott), not far from the West Side Grounds, where a new ballpark was to be built at an estimated cost of $30,000. The site was large enough to also accommodate other building lots. Among other real estate held by the old corporation was the property in Hot Springs, Arkansas, where the team held its spring training. Hart’s new corporation, of which he was president, signed a 10-year lease to play ball on the yet-to-be-built west side grounds, owned by the old corporation. The new corporation was chartered by Hart, Sherman, and Barrett, but all of the original stockholders had the opportunity to buy into the new corporation.101 Spalding, Walsh, and Anson all took advantage of the opportunity, and Anson stayed on as field manager.

The reorganization was finalized on December 17, 1892, and when it was done A.G. Spalding, his brother Walter, and John R. Walsh together held 640 shares; the estate of J.W. Brown held 132 shares; Anson owned 130 shares; and Hart held 83 shares. The remaining 15 shares belonged to Frank Andrews.102 Hart increased his holdings over the next decade, assuming majority ownership in 1902. Spalding incorporated his holdings of real estate, his sporting-goods business, and his White Stockings stock in New Jersey with capital stock of more than $4 million. He also purchased the Reach Sporting Goods Company for $100,000 after Reach defaulted on an 1887 loan he had obtained from Spalding.

Spalding stood at the peak of the sporting-goods industry, with offices in 23 US cities, stores in 65, and a payroll numbering 3,500 employees, who turned out more than one million baseball bats a year.103 After the new incorporation, he still had a substantial financial interest in the White Stockings, but stepped back from active involvement with the club, and over the next decade reduced his financial interests in the club as well, selling his remaining shares in 1902.

Spalding eventually moved to California and made an unsuccessful run for the US Senate. Through his sporting-goods company he continued to publish the annual official NL guide and he wrote America’s National Game, part memoir, part history, in 1911, which, despite its many shortcomings, was the first true effort to tell baseball’s history. Spalding remained a force in the game until his death in 1915. Referred to as the Father of Baseball by the early twentieth century, Spalding used that respect to help promote his desire that baseball be recognized as a purely American sport in origin. That overzealous desire led to one of his more dubious “contributions” to the game: the propagation of the myth that Abner Doubleday invented baseball.

Spalding died of apoplexy at age 65 on September 9, 1915, at his home in Point Loma, California. He was survived by three children and his second wife, to whom he left the bulk of his estate, valued at $600,000.104

In 1893 Hart moved the team again, to the newly built West Side Park,105 which was regarded as the finest baseball edifice of its day. He had a telephone installed in his box seat so he could conduct business while watching games. The field was huge, 540 feet to left and right (150 feet longer than the old west side grounds). The grandstand contained 3,000 folding chairs and 500 opera chairs. For the gentler class, 500 armchairs occupied 56 private boxes. There were 4,500 seats in the covered pavilion and another 8,000 in the open bleacher seats. Two bathrooms were located on the top floor of the brick building used by the ticket sellers. The ground floor also featured a directors room and the ladies retiring room. Dressing rooms with hot and cold water, showers, and closets were provided for each team.106

On August 5, 1894, a fire broke out during a game at West Side Park, causing $15,000 in damage. While there were no deaths, a reported 500 people were injured, mostly while trying to escape through a barbed-wire fence that separated the bleachers, where the fire originated, from the field. “The wires were strung with hair and strips of skin and flesh.” The tightly wound barbed-wire fence, which reached to a height of eight feet and extended along the length of the 25-cent seats, had been erected to “keep the ardent 25-cent crank from getting down in the field and killing the umpire. Its necessity had been suggested from a little incident that happened on the South Side grounds two years ago when the crowed swarmed out into the field to curse the umpire and stopped a game that Chicago stood sure to win.”107

Quick thinking by some of the players and President Hart probably saved the lives of the 1,600 patrons seated in the bleacher section. “The imperiled and fear-crazed crowd bucked against the barbed fencing. Their mad rush to get away from the advancing flames resulted in the injury of scores.” Players Jimmy Ryan and Walt Wilmot helped fans escape through the barbed-wire fencing by “using their bats like blacksmiths” to create a gap. Hart directed the destruction of a 50-foot section of the fence to allow access to the field. “Five minutes after the last spectator had got out of reach of the flames every seat was being consumed.” A cigar stub tossed into rubbish in the stands was blamed for the fire.108

“Four hundred feet of the buildings extending from the grand stand along Lincoln Street was burned to cinders. … Nearly one-half of the stands of the park [were] either completely destroyed or badly damaged.” The damage extended outside the ballpark to the sidewalks and street. During the blaze, many onlookers gathered outside, and as many were interested in the fires and casualties as wanted to know “how the game between Chicago and Cincinnati had been going when interrupted. And even in the presence of calamity there were many expressions of satisfaction that Chicago was so well ahead [they led 8-2 in the seventh inning] that the game had been practically won before the fire king called it off.”109 Despite the disaster, nary a game was missed. The damaged section of the ballpark was roped off, and the park was ready for play the next day.

First baseman and team captain Adrian “Cap” Anson played for Chicago’s National League club for 22 seasons from 1876 to 1897, recording more than 3,000 career hits. He also played an instrumental role in enforcing baseball’s segregated color barrier against Black players. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

Adieu to the Captain

James Hart and Adrian “Cap” Anson had a strained relationship stemming from Anson having been passed over for president in favor of Hart. Anson was also bitter over a failed attempt to buy the club, and he blamed both Hart and Spalding for impeding him in those efforts. He publicly blamed Hart for the team’s struggles on the field, complaining that he was miserly and refused to obtain good players because he didn’t want to pay the salaries they would command. This was merely a continuation of the budgetary penury practiced by Spalding, under whose stewardship the team developed a reputation for cheapness. As president, Spalding frequently sold off high-priced players, replacing them with younger and cheaper talent.

Anson’s long-term contract expired in January of 1898 and Hart did not renew it, almost certainly with the blessing of Spalding, even though, as president, Hart did not need Spalding’s approval. By this time Spalding was no longer the majority shareholder, having sold shares to Walsh, who became the majority shareholder by the end of 1897.110 Perhaps to console Anson for his dismissal, Spalding offered to sell him controlling interest in the team at $150 per share and gave Anson 60 days to raise the funds. But at the April 15 deadline, Anson did not have the money and the deal fell through. An incensed Anson accused Spalding of duplicity, charging that “there was never any intention on the part of A.G. Spalding and his confréres to let me get possession of the club.”111 Anson was probably right, in that Spalding certainly realized the likelihood of Anson’s coming up with the necessary cash was highly unlikely. For his part, Anson was more likely speaking out of frustration, as he was genuinely angry at having been denied for a second time an opportunity play a significant front-office role with the club. The end of the Anson era in Chicago was bitter and ugly, hardly becoming the career of a legend. The Chicago Tribune estimated that since he began to play ball as a teenager in Marshalltown, Iowa, he had piled up 7,000 hits.112

Hart maintained that the decision to let Anson go was made by the stockholders, who felt that the fans desired a change of management. He praised Anson’s long and faithful service to the club, wishing him the best in his future endeavors, and said, “There is not now, and never has been, friction between Captain Anson and myself.”113 Hart and Anson belied this “lack of friction” in a contentious exchange of letters published in the Chicago Tribune later that year.

Seeking to defend his motives, Hart explained Anson’s financial connections to the White Stockings. His contract called for a fixed salary plus a percentage of net profits each year. However, according to Hart, for a variety of reasons, there were no profits in any year from 1890 to 1893. Nevertheless, in two of those years Anson was paid a sum “nearly double that called for in his contract.” And in a third, a debt to the club in the amount of $2,600 for previously purchased shares of stock was forgiven. In 1897 Anson once again took an advance from the club, this time in the amount of $2,400, “which at the present time stands charged to him on the books of the club, and it has never been paid.”114

Anson rebutted, claiming that Hart overstated losses in the years 1890-93. Regarding the corporate reorganization, he asserted that Spalding had offered him the chance to “swing the deal myself.” While he was unable to take over the club, he did purchase 130 shares in the new corporation. “When I took the extra shares of the stock … I was guaranteed that my contingent fees should pay for the stock that was assigned to me. I deny emphatically that I owe the club $2,400. … I worked for the club for a period of time extending over twenty-two years, my contract calling for a stated salary and 10 per cent of the net profits … but I have never been allowed to see [the books], and whether I have had all that was coming to me or not is an open question in my mind.”115

After Anson was released, the sportswriters began referring to the team as the Orphans, which was just as well, since Hart changed the team uniform to maroon stockings to better hide the dirt.116 They were never to bear the moniker White Stockings again, as three years later the upstart American League christened its Chicago team the White Stockings, shortened by writers to White Sox, forever co-opting the name.

Spalding planned a testimonial dinner for Anson, raising $50,000 for a tribute to the longtime star. “It seems a pity,” said Spalding, “that a man like Anson should be allowed to drop from sight without the people being given a chance to show their high esteem of him.”117 Anson, however, refused the honor, saying, “I don’t know as I am yet ready to say that I am out of baseball. I am neither a pauper nor a rich man, and prefer to decline. The public owes me nothing. … [T]he kind offer to raise a large public subscription for me … is an honor and compliment I duly appreciate. … At this hour I deem it both unwise and inexpedient to accept the generosity so considerately offered.”118

In the fall of 1899, Hart made a costly error when he granted Charles Comiskey the right to relocate his St. Paul franchise to Chicago’s south side, where Comiskey erected a ballpark just north of the South Side Grounds the White Stockings had abandoned just a few years earlier. At the time the American League (née Western League) still held minor-league status, and did not seem a threat to Hart’s business. However, when the new team adopted the nickname White Stockings, no longer used in reference to Hart’s club, and the American League declared itself a “major league” the following year, the situation took on a whole new light. And when one-third of the 30 players who donned the NL Chicago uniform fled to the new league in 1901, and another eight the following year, it became apparent that the interlopers were far more threatening than Hart had assumed. Chicago lost so many players in the early days of the AL-NL war that sportswriters dubbed them the “Remnants.”

Al Spalding briefly returned to active involvement in league affairs at the winter meetings in December of 1901. He had not been publicly involved since he turned over control of the franchise a decade earlier, but was determined to head off John Brush’s proposal to turn the league into a trust consisting of eight franchises. The battle was played out in the contest for league president. Spalding ran against his old pal Nick Young, who was nominated by the Freedman trust faction. The vote was deadlocked at 4 each for 25 rounds of balloting, at which point “the Young faction left the meeting room, whereupon Col. Rogers, acting as chairman, declared Mr. Spalding elected. Mr. Spalding then assumed charge of the league’s records, but the Young faction refused to acknowledge Spalding’s election and secured an injunction, to which Mr. Spalding filed a demurrer.”119 The case dragged on for three months before the Spalding demurrer was overruled. The league then met on April 1, whereupon Spalding resigned his challenged presidency, declaring, “I am prompted in this action solely by the belief that prolonging a factional political warfare into the playing season would be distasteful to the public, injurious to the National League in particular and to professional base-ball in general.”120 Young was elected secretary-treasurer, and the executive duties were turned over to a three man commission consisting of Brush as chairman, Soden, and Hart.

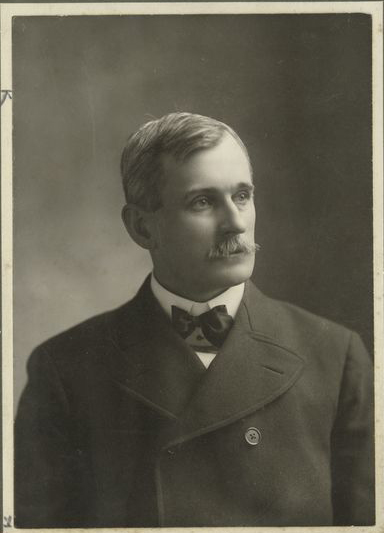

James A. Hart succeeded Albert Spalding as the Chicago Cubs president in 1891 and then took over majority control of the team from 1901 until 1905. (A.G. SPALDING COLLECTION)

James Hart