September 28, 1919: Giants and Phillies record 51 outs in 51 minutes, the fastest game in major-league history

More than one major-league regular season has ended with a memorable contest between teams representing the Big Apple and the City of Brotherly Love. The New York Mets’ David Cone struck out 19 Philadelphia Phillies on the last day of the 1991 season; Philadelphia Athletics rookie Art Ditmar notched his first major-league win over the New York Yankees to close out the 1954 season in the last game the A’s played before moving to Kansas City; and Dick Sisler’s game-winning 10th-inning home run against the Brooklyn Dodgers in their 1950 season finale clinched the Phillies’ first National League pennant in 35 years.1

More than one major-league regular season has ended with a memorable contest between teams representing the Big Apple and the City of Brotherly Love. The New York Mets’ David Cone struck out 19 Philadelphia Phillies on the last day of the 1991 season; Philadelphia Athletics rookie Art Ditmar notched his first major-league win over the New York Yankees to close out the 1954 season in the last game the A’s played before moving to Kansas City; and Dick Sisler’s game-winning 10th-inning home run against the Brooklyn Dodgers in their 1950 season finale clinched the Phillies’ first National League pennant in 35 years.1

At the end of the 1919 season, two teams from these cities that love to hate one another came together for a game that has no equal. On September 28, the Giants and Phillies played the fastest nine-inning game in major-league history. Playing “under the shadow of Coogan’s Bluff[,]”2 they needed only 51 minutes to record 51 outs.

The Giants entered the last day of their season-ending series against the Phillies locked into second place, their pennant chase over a week earlier. The Phillies also had nowhere to go in the standings, buried in last place for the first time in 15 years. Meanwhile, the attention of the baseball world had turned to the ill-fated coming World Series between the Cincinnati Reds and the Chicago team forever known as the Black Sox.3

The Giants moved their scheduled season-ending September 29 contest at the Polo Grounds back one day in order to hold a Sunday doubleheader, which they knew would draw a larger crowd.4 With the offseason calling, players on both sides were interested in finishing the games quickly.

Although baseball has never been bound by time limits to determine when a game was over, recording the length of games had long been a box-score staple. The duration of the very first game played by Al Spalding and the Chicago White Stockings in the National League’s inaugural 1876 season – 1 hour and 50 minutes – was included on page one of the next day’s Chicago Tribune box score.5

A record of how long a game lasted was considered so intrinsically part of baseball box scores that when Baseball Magazine published a reformatted version of what it considered the very first box score, compiled by Henry Chadwick (the Father of Baseball), in the September 10, 1859, issue of the New York Clipper, they included the game’s duration, a reported three hours – even though the game’s length didn’t appear in the original box score or accompanying game summary.6

Along with Kewpie dolls and jazz music, speed was “keen” in the second decade of the twentieth century. Advancements in transportation technology had spawned the golden age of ocean liners, the rise of the automobile and the dawn of aviation. Things done faster than ever fascinated millions. Newspapers stoked that preoccupation with widespread reporting on the fastest passage across the Atlantic,7 speed records for car travel between cities,8 the fastest airplanes,9 and the fastest baseball games.10

Despite all this interest, in September 1919 there wasn’t universal agreement on what the record was for the swiftest regular-season major-league game. The Illustrated Daily News11 claimed after the record-setting Giants-Phillies game that the fastest previous game was a 56-minute contest between the Giants and Brooklyn Dodgers a year earlier.12 In its summary of the 51-minute game, the Philadelphia Inquirer identified a 55-minute game played just a week before as the former record-holder.13

According to the Illustrated Daily News, both the Giants and the Phillies “agreed to go after the speed record” before the first game of the doubleheader.14 Such an agreement would have been between Giants acting manager Christy Mathewson, who had been filling in for legendary skipper John McGraw ever since the pennant race was lost,15 and Phillies player-manager Gavvy Cravath, who had taken over two months earlier.

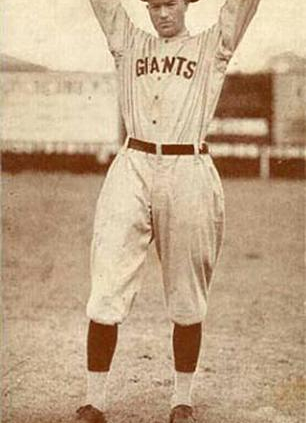

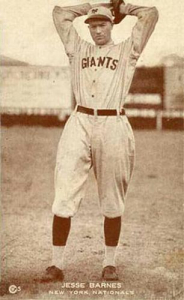

The Philadelphia Inquirer put attendance at 14,000, while the New York Tribune claimed nearly 20,000 present “in good humor and entered into the final rites with as much zest as the players.”16 Mathewson sent Jesse Barnes to the mound, looking for his league-leading 25th win on the season. Cravath countered with Lee “Specs” Meadows,17 a midseason acquisition from the St. Louis Cardinals who was hoping to avoid his league-leading 20th loss.

Behind Barnes, the Giants were led by captain Art Fletcher, left-handed-hitting cleanup hitter and former Chalmers (MVP) Award winner Larry Doyle. Also playing for New York were a pair of youngsters: 22-year-old hustling right fielder Ross Youngs, who led the team in hitting, and switch-hitting 21-year-old rookie infielder Frankie Frisch, who joined the Giants in June straight off the Fordham University campus. Not in the lineup were regulars Hal Chase and Heinie Zimmerman, the former benched and the latter suspended, in part for their repeated efforts to bribe teammates to throw games.18

Facing Barnes, the Phillies featured .308-hitting right fielder Irish Meusel, older brother of future Yankee stalwart Bob Meusel, slugger Cy Williams,19 and slick-fielding shortstop Dave Bancroft. First baseman Fred Luderus was playing in his 532nd consecutive game, a modern-era National League record.20

The Phillies got on the board first, as a throwing error by Fletcher at shortstop allowed Lena Blackburne to score after he’d doubled to left field and moved to third on a groundout. A lifetime .214 hitter making his last major-league start,21 Blackburne is best known for creating baseball rubbing mud. A concoction he came up with in the 1930s to remove the slippery sheen from baseballs, as of 2022 it was still being used by every professional baseball team.22

The Giants knotted the score in the bottom of the second on a single to right by Doyle, Fletcher’s double and Frisch’s groundout to shortstop. They added three more runs in the third on a two-RBI single by two-time Federal League batting champ Benny Kauff off the glove of Luderus,23 and a bases-loaded single by George “Highpockets” Kelly that plated Kauff.24 Doyle, who had singled ahead of him, was thrown out attempting to score from second on Kelly’s single. The Giants were now up, 4-1.

After allowing the Phillies a run in the first, Barnes’s “twisters” tied them in knots,25 retiring the next 16 batters in order, with only one ball leaving the infield.

Barnes was helped no doubt by the Phillies’ commitment to play quickly. The Illustrated Daily News noted that “the men went up intent on smacking the first pitch” and “did so for the most part.”26 The hometown fans “didn’t object” to the game’s fast pace, according to the New York Tribune, as the “free hitting and didn’t care spirit of play made possible many bits of brilliant work.”27 The paper identified Frisch as the brightest of “the luminaries” on defense and noted that the bespectacled Meadows “wasn’t inclined to over-exert himself. … [He] just pitched.”

According to the New York Sun, it was about the sixth inning when the crowd “realized the teams were really hustling,” “running to and from their positions, urged on by [home-plate] Umpire Klem.”28 The Sun also noted how only five or six pitches retired the side in some innings.

The Giants tacked on another two runs in their half of that sixth inning. Rookie catcher Earl Smith drove in Kelly, after he hit a leadoff double. Pitcher Barnes followed with his career-high fifth double of the season, but Smith was thrown out at home by rookie left fielder Bevo LeBourveau, earning his fifth outfield assist in just 16 games. Barnes advanced to third on the play at the plate and scored on a fly ball from George Burns.29

Bancroft ended Barnes’s streak of batters retired with a two-out single in the seventh, but failed to score. Phillies’ singles in the eighth and ninth also failed to spark rallies. The New York Times claimed Bancroft “walk[ed] into a putout” when his check swing produced the final out of the game, calling it “the only part of the game in which real effort was lacking.”30

Barnes allowed five hits and no walks for the victory, and needed only 64 pitches, a new major-league low for a nine-inning game, according to the New York American.31

There were 70 plate appearances in the game by the two teams combined. If each team took one minute to get on and off the field the end of each half-inning (16 transitions in total), the average plate appearance would have been exactly 30 seconds. Lightning fast, by modern standards.

The Giants triumphed in the second game of the doubleheader, conducted at a more leisurely pace judging by the lack of attention to the game’s length in newspaper reports the next day. Late in that game, as Mathewson walked out to a coaching line with a glove in his pocket, the crowd clamored for him take the mound. Three years removed from his last major-league appearance, “the retired idol merely smiled – a bit sorrowfully, maybe – and gazed across the field where the shadows were gathering in upon the baseball season of 1919.”32

Alongside the New York Times game summary in the next day’s newspaper was an announcement that New York would soon have a professional football team. They would play home games at the Polo Grounds and borrow the name of the baseball team that had long called that oddly-shaped field home, the New York Giants.33

Acknowledgments

This article was fact-checked by Kevin Larkin and copy-edited by Len Levin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author used information published in the New York Herald and New York Times in the days leading up to this game and consulted Janice Johnson’s SABR biography of Jesse Barnes. The Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Almanac.com, and statscrew.com/baseball websites also provided pertinent material.

https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/NY1/NY1191909281.shtml

https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1919/B09281NY11919.htm

Notes

1 Other memorable New York-Philadelphia season finales include the Phillies dealing the Mets’ Jack Fisher a club-record-tying 24th loss in 1965, a number not matched by any major-league pitcher since; New York Giant Willie Mays going 3-for-4 against the Phillies to eke out the NL batting title over teammate Don Mueller in 1954; Jackie Robinson leading the Brooklyn Dodgers in a come-from-behind 14-inning win over the Phillies in 1951 to force a three-game playoff for the pennant with the Giants; Lou Gehrig driving in a pair of runs to give him an AL-record 185 RBIs in a 1931 drubbing of the pennant-winning Athletics that denied Lefty Grove a modern-era club-record 32nd win; and Athletics knuckleballer Eddie Rommel defeating the New York Yankees in 1924 to deny them a fourth consecutive AL title.

2 “Giants End Season with Record Wrecking Spree,” New York Sun, September 29, 1919: 17.

3 Philadelphia Inquirer, September 28, 1919: 1.

4 The five largest baseball crowds at the Polo Grounds in 1919 were for doubleheaders, and five of the 10 games with the highest attendance that year were played on a Sunday.

5 “Sporting News,” Chicago Tribune, April 26, 1876: 1.

6 Mike Pesca, “The Man Who Made Baseball’s Box Score a Hit,” NPR.org, July 30, 2009, https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=106891539.

7 Many newspapers reported in April 1907 how the Cunard steamship Mauretania broke by one minute the transatlantic crossing record held by its ill-fated sister ship, the Lusitania. White Star Line executive J. Bruce Ismay’s reckless entreaties for more speed during the 1912 maiden voyage of the Titanic precipitated its demise and brought an end to public fascination with Atlantic crossing records. “Mauretania Breaks Record,” Brooklyn Eagle, April 17, 1908: 1.

8 For example, in February 1918, a Chalmers Hotspot (produced by the company whose owner sponsored the eponymous Chalmers Award, a predecessor to the Most Valuable Player Award), was hailed for recording the fastest time between Oklahoma City and Tulsa – 3 hours and 28½ minutes. “Claims Record Drive,” Baltimore Sun, February 10, 1918: 8.

9 The 160 mph Kirkham triplane was named as the world’s fastest by the Burlington (Kansas) Republic in November 1918. “Fastest Airplane Built in U.S.,” Burlington Republic, November 29, 1919: 1.

10 The author identified dozens of reports of the fastest baseball games for the season or for a ballpark throughout the 1910s. In the first three weeks of September 1919 alone, the Mamaroneck (New York) Paragraph described a game between the Philadelphia Colored Giants and the All-Stars as “the fastest game on the local diamond this season,” the Capital Times (Madison, Wisconsin) called a industrial league game the “fastest ball game of [the] year in Madison,” and the Long Branch (New Jersey) Daily Record declared a local game against a semipro team “the fastest game ever played on the Norwood Oval.” “Athletic Notes,” Mamaroneck Paragraph, September 18, 1919: 6; Capital Times, September 1, 1919: 5; Long Branch Daily Record, September 6, 1919: 5.

11 The original name of the tabloid newspaper now known as the New York Daily News.

12 The New York Times summary of the 56-minute game in 1918 claims only that it was the fastest game played at the Polo Grounds in 1918. Both teams may have been in a hurry to get the game over in order to read about a bill just signed by President Woodrow Wilson that expanded World War I military registration to require all 18- to 45-year-old American men to register by September 12, in order to send what the Times estimated at 4 million fighting men to France by June 1919. Thanks to the Armistice signed in November 1918, a large mobilization proved unnecessary. “Giants Waste No Time on Dodgers,” New York Times, August 31, 1918: 5. “President Signs 18 to 45 Draft Bill and Gives Out Ringing Proclamation; Over 12,000,000 Will Register Sept. 12,” New York Times, September 1, 1918: 1.

13 “Less Than Hour to Beat Phillies,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 29, 1919: 14; “Dodgers Down Reds in Fastest Game,” Binghamton (New York) Press, September 23, 1919: 18.

14 “Fifty Minutes for First Game Sets New Mark,” New York Illustrated Daily News, September 29, 1919: 19.

15 McGraw handed Mathewson the reins for the rest of the season after the Reds defeated the Giants 3-0 on September 15, knocking them 9 games back with 12 games to go, just about eliminating New York from the pennant race. “Congratulations to Pat Moran,” New York Herald, September 16, 1919: 19.

16 Inexplicably, Baseball-Reference.com lists 14,000 in attendance for the doubleheader opener and 20,000 for the nightcap. “20,000 Attend Baseball Wake on Local Field,” New York Tribune, September 29, 1919: 10; “Less Than Hour to Beat Phillies.”

17 In 1915 Meadows became the first major-leaguer to wear glasses during a game in nearly 30 years. Gregory H. Wolf, Lee Meadows SABR biography, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/lee-meadows/.

18 Chase and Zimmerman were banished by McGraw in mid-September after Kauff had reported their efforts to bribe him. Zimmerman’s suspension was widely reported, while Chase’s absence was attributed to injury. Chase was relegated to coaching at first base after McGraw turned the team over to Mathewson. “Zimmerman Sent Home by M’Graw,” New York Herald, September 12, 1919: 19; “Curves and Bingles,” New York Times, September 28, 1919: 117; Martin Kohout, Hal Chase SABR biography, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/Hal-Chase/; David Jones, Benny Kauff SABR biography, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/Benny-Kauff/.

19 To this point in his career, Williams had collected one NL home run title (in 1916) and 49 career home runs. Before he retired, he won three more home-run crowns and was, from 1923 to 1929, the NL career home-run king. Cappy Gagnon, Cy Williams SABR biography, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/cy-williams/.

20 The NL record for consecutive games played at that time was held by outfielder Steve Brodie, who appeared in 727 consecutive games between 1891 and 1897. Luderus broke Eddie Collins’s “iron man” modern record of 478 straight games in early August. He played only one more game before the streak ended, as he was unable to play on Opening Day the next season due to a bout of lumbago. He held the modern NL record until 1927, when he was passed by St. Louis Browns outfielder Eddie Brown. “Luderus Day, Sept. 23,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 19, 1919: 15; Joe Dittmar, Fred Luderus SABR biography, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/fred-luderus/; William Akin, Steve Brodie SABR biography, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/Steve-Brodie/.

21 After this game Blackburne played in just two more major-league games. By then a full-time coach for the Chicago White Sox, he pinch-hit in a game in June 1927; and in June 1929, while managing the White Sox, he elected to pitch to the final batter in a 17-2 blowout loss. Stephen V. Rice, Lena Blackburne SABR biography, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/Lena-Blackburne/.

22 Made using a proprietary mixture that famously includes mud taken from the bank of the Delaware River, rubbing mud is supplied to major-league teams exclusively by the Lena Blackburne Baseball Rubbing Mud company. Rice, Lena Blackburne SABR biography; Dan Barry, “He’s Baseball’s Only Mud Supplier. It’s a Job He May Soon Lose,” New York Times, July 30, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/07/26/sports/baseball/baseball-mud-supplier.html.

23 Allen Lewis, “This Was the Fastest Major League Game Ever!” Baseball Digest, August 1978: 86.

24 Kelly, a rarely used utility player for the Giants before military service took him away from baseball in 1918, had been promoted from Double-A Rochester in August when regular first baseman Hal Chase was suspended for “myriad misdeeds and gambling connections.” Mark Stewart, George Kelly SABR biography, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/george-kelly/.

25 “Giants End Season with Record Wrecking Spree.”

26 “Fifty Minutes for First Game Sets New Mark.”

27 “20,000 Attend Baseball Wake on Local Field.”

28 “Giants End Season with Record Wrecking Spree.” The New York Times, in contrast, claimed “there was no unusual effort … to make a speed record until the Phils’ half of the ninth.” “Giants Finish with Pair of Victories,” New York Times, September 28, 1919: 20.

29 Burns led the NL with 40 stolen bases in 1919, the third straight season in which he’d stolen that many. He also topped the league with 86 runs scored, the fourth time he’d led in that category.

30 “20,000 Attend Baseball Wake on Local Field.”

31 The current record for the fewest pitches thrown in a nine-inning complete game is 58, by Red Barrett of the Boston Braves in his August 10, 1944, shutout of the Cincinnati Reds. Janice Johnson, Jesse Barnes SABR Biography, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/jesse-barnes/.

32 “Giants End Season with Record Wrecking Spree.”

33 “New York to Have Pro Football Team,” New York Times, September 29, 1919: 20.

Additional Stats

New York Giants 6

Philadelphia Phillies 1

Game 1, DH

Polo Grounds

New York, NY

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.