Silver Stadium (Rochester, NY)

This article was written by Kurt Blumenau

For close to 70 years, the rich baseball history of Rochester, New York, centered around a lopsided ballpark at 500 Norton Street. The park known over the years as Red Wing Stadium and Silver Stadium hosted decades of minor-league baseball and a year of Negro National League play. Like all minor-league parks, its occupants were transitory. But what a list: Johnny Mize, Stan Musial, Red Schoendienst, Earl Weaver, Eddie Murray, and the Ripken family were just a few of the players and managers who lit up the stadium between 1929 and 1996.

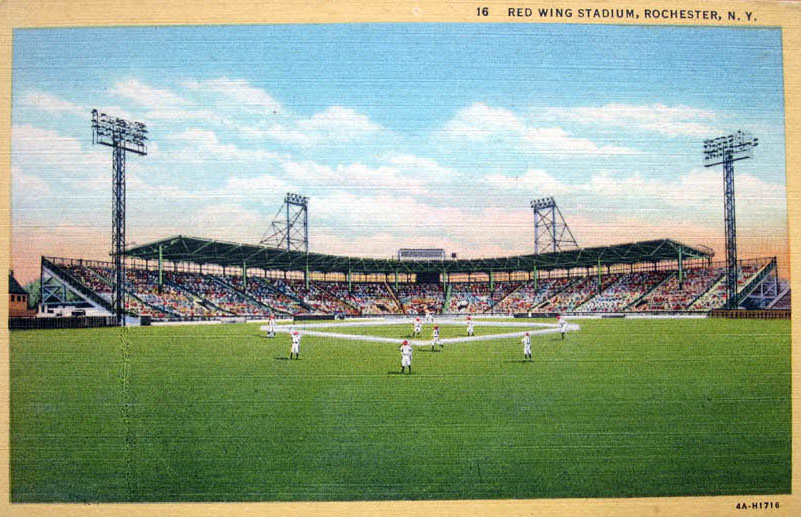

Baseball in Rochester has been synonymous with the International League1 since 1912 (when the Eastern League was renamed), and with the Red Wings name since 1928. The new concrete ballpark built on a former apple orchard2 on the city’s northeast side shared the team’s name — Red Wing Stadium — when it opened in the rain on May 2, 1929. The Red Wings of the 1920s were a Double-A farm team of the St. Louis Cardinals, and the parent club owned both the team and its park. Construction costs were initially estimated at $300,000, but a report on Opening Day cited the cost at almost $400,000.3 One news report of that first game enthused, “The new ball park is a wow!” adding, “Everything about the new stadium is very much like the big leagues.”4

The ballpark consisted of a roofed single-deck grandstand extending past first and third base, with an uncovered bleacher section along the left-field line. Photos from the 1950s show the bleachers wrapping around and extending behind the left-field fence, but the seating beyond the fence was later removed.5 While the outfield angles of the park doubtless changed in its early years, its later appearance was consistent with dimensions given in a 1957 news story: 315 feet down the right-field line, 320 to left, 405 to dead center, and 425 feet to the left of the 30-foot-high scoreboard in left-center field — probably the park’s most noteworthy feature.6 In July 1964, Mack Jones of Syracuse became the first batter in memory to clear the towering scoreboard with a home run.7 Rochester slugger Jim Fuller, known for his tape-measure shots, also accomplished the feat in June 1976 against Charleston.8

Red Wing Stadium’s capacity was originally listed at about 12,000, but about 15,000 were on hand for that first game in 1929 to see the Wings lose, 3-0, to the Reading Keys.9 The park’s quoted capacity varied slightly throughout its history. Capacity figures over the years included 15,000 (1940), 14,745 (1957), 13,745 (1971), 14,045 (1979) and 11,503 (1994, following extensive renovations).10

On Opening Day 1931, Red Wing Stadium set a baseball attendance record that it never topped: 19,006 paying customers streamed through the gates to see Rochester lose, 4-1, to the Newark Bears. News reports suggested that 21,000 people might have been on hand when those with free passes — and those sneaking in — were included. A portion of right field was roped off to contain the overflow crowd.11 The largest crowds of any type in the stadium’s history are believed to be the 30,000 people who turned out in 1987 and 1988 to see a pair of institutions unimaginable in 1931: the Grateful Dead and U2.12

The Wings were a powerhouse team in the ballpark’s first years, claiming three straight IL championships from 1929 to 1931 and winning more than 100 games each year. Red Wing Stadium was quick to adopt lights, with the first night contest played between the Red Wings and Newark Bears August 7, 1933 — two years before the first major-league night game.13 Radio broadcasts were also part of the action from the park’s earliest days, with Red Wings games aired on WHEC radio as early as 1928.14 The team’s first radio broadcaster, Gunnar Wiig, went on to Rochester-area fame as an executive at local TV stations.15 Probably the best-known voice of the Red Wings was Jack Buck, who spent the 1953 season in Rochester before moving on to earn recognition from the Baseball and Football Halls of Fame.16

Marquee names from the early years of Red Wing Stadium, in addition to any number of future Cardinals, include Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig, who played there on a 1930 barnstorming tour.17 Ruth also appeared at the park in 1934 and 1941. A group of Negro League legends including Josh Gibson, Mule Suttles, Ray Dandridge, and Buck Leonard played there in a game between the Homestead Grays and Newark Eagles in August 1938.18 Future Hall of Famer Billy Southworth managed the Wings for parts of five seasons between 1928 and 1932, returning in 1939 and 1940. Another future Hall of Famer, Walter Alston, played parts of three seasons at first base for Rochester.

Perhaps the most colorful story from the park’s first few decades belonged to Rochester native Johnny Antonelli. He pitched a no-hitter for Rochester’s Jefferson High School at Red Wing Stadium while just a sophomore, and also threw touchdown passes there as the football team’s quarterback. In June 1948 he pitched another no-hitter in a semipro game at Red Wing Stadium that was set up, in part, for the benefit of big-league scouts who hadn’t been able to see him play high school ball that year.19 Antonelli went on to pitch parts of 12 seasons in the major leagues, make six All-Star teams, and win a World Series with the 1954 New York Giants. After retirement, he returned to Rochester and became successful in the tire business, frequently sponsoring ads and events at the ballpark.

Two other Red Wing Stadium fixtures from the early decades never played an inning on the field. Victor “Red” Smith, an enthusiastic rooter with a booming voice, roamed the stadium for decades, leading cheers. He became so synonymous with Rochester baseball that the team held nights in his honor in 1957 and 1965, the latter to celebrate his 80th birthday. When Smith died in 1975, his pallbearers included Wings manager Joe Altobelli, general manager Ed Barnowski, and five players.20 Another superfan, Bill Nill, was less outgoing but just as devoted. He began attending Rochester ballgames in 1909 and was getting ready to go to another when he died in August 1978. The stadium flag hung at half-staff in Nill’s honor,21 and his ashes were buried beneath the park’s bleacher section, his favored seating.22

A new, single-season tenant for Red Wing Stadium arrived in 1948 when the New York Black Yankees of the Negro National League moved to the Flower City from Yankee Stadium.23 Local news stories at the time did not explain the reasons behind the unusual move, but the integration of the major leagues by the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947 had reduced attendance at Black Yankees games, and team owner James Semler could no longer afford the rental.24 Suttles served as a coach, while future big-leaguer George Crowe played on the team. The Black Yankees received limited local press coverage; reports years later indicated that the team shut down operations before the season’s scheduled end, posting a 9-35 record.25 The Black Yankees and Indianapolis Clowns resurfaced at Red Wing Stadium for one-day exhibitions in 1955 and 1956. Meanwhile, first baseman Tom Alston broke the color barrier for the Red Wings on June 30, 1954, having broken the color barrier with the Cardinals earlier in the season.26

Early on, Red Wing Stadium hosted high school and professional football games. Two teams from the fledgling, ultimately unsuccessful American Football League called the field home in 1936 and 1937. The first, the Rochester Braves, lasted only one game; the second, the Rochester Tigers, persisted for two seasons.27 In 1949, Rochester opened a 20,000-seat football facility, Aquinas Stadium, later renamed Holleder Stadium. This facility siphoned off football games, as well as concerts and soccer games that otherwise might have taken place at the baseball park in subsequent decades.

Still, Red Wing Stadium had a place in civic life that went beyond the Red Wings. It played host to drum-and-bugle corps exhibitions and multiple religious rallies, including a “candlelight holy hour” in 1949 at which more than 20,000 attendees prayed for peace.28 Future world champion boxer Carmen Basilio, a Syracuse-area native, defeated Tony DePolino of Buffalo as part of a full card of bouts at the ballpark in September that same year.29 In August 1954, the park hosted a “Polio Benefit Vaudeville Revue” concert before a ballgame. Radio and TV star Lu Ann Simms headlined. Lower on the bill were a pair of Rochester-bred musicians still in their teens, pianist Gap Mangione and his horn-playing brother Chuck.30 And in July 1955, 400 people gathered at Red Wing Stadium to be “evacuated” to suburban Palmyra as part of New York state’s first civil defense mass evacuation test.31

The late 1950s and early 1960s brought change. Following the 1956 season, the Cardinals announced plans to sell both the team and the park, with the intent of pulling out of Rochester. A community ownership scheme was identified as Rochester’s best chance to keep the team.32 Local businessman Morrie Silver led a stock sale that raised the money to keep the Red Wings in town, with the team and park under the ownership of a new organization called Rochester Community Baseball. Silver later served as president and general manager of the Red Wings, turning a money-losing operation into one more profitable than the other 23 Triple-A teams combined.33 He devoted such crucial service to the team that the ballpark was renamed Silver Stadium in his honor in August 1968.34

The Cardinals lingered for four more seasons, then moved their Triple-A affiliation elsewhere following the 1960 season.35 The Red Wings connected with the Baltimore Orioles, forming a long and fruitful connection that lasted through Silver Stadium’s final days and beyond.

Rochester hitched its wagon to Baltimore just as the Orioles were developing into a juggernaut. As a result, the fans at Silver Stadium got an early look at many of the stars who made those teams so strong. Between 1961 and the park’s closing in 1996, Red Wings teams won five Governor’s Cups — given to the winner of the IL playoffs — and finished runner-up another five times. The ballpark hosted many playoff and postseason games, including a memorable single-game faceoff between Rochester and the Richmond Braves to break a tie for the 1967 regular-season championship. Richmond pitcher Jim Britton, a native of the Buffalo area, dominated the Wings into the ninth inning as Richmond won 2-0. During the final inning, Britton’s father, Russell, suffered a fatal heart attack in the third-base box seats while cheering on his son.

Eight Red Wings won the IL’s Most Valuable Player award during the Red Wing/Silver Stadium years, while five more won the league’s Most Valuable Pitcher honor.36 Wings managers Weaver, Cal Ripken Sr., Altobelli, and Frank Robinson all went on to manage the parent club. Silver Stadium also hosted many exhibition visits by the Orioles, including a memorable game on August 8, 1974, that featured a rehabilitation start by Jim Palmer,37 a come-from-behind win for the Wings, and the announcement of President Richard Nixon’s resignation.

Race riots in Rochester in 1964 spared the ballpark direct damage, though one game had to be postponed and the times of others changed to accommodate a temporary curfew.38 Rochester and its stadium also dodged the chaos that enveloped other upstate New York ballparks in the 1960s. The International League’s Buffalo Bisons moved most of their home games from Buffalo’s War Memorial Stadium to Niagara Falls after 1967 rioting. At a rare game in Buffalo in 1969, a gang of youths invaded the clubhouse and robbed players at knifepoint.39 Meanwhile, Syracuse’s MacArthur Stadium suffered significant damage in May 1969 from a fire that broke out a few hours after the completion of a game between the Red Wings and Syracuse Chiefs.40

Still, as the 1970s arrived, Silver Stadium was showing its age. The team invested $125,000 in the park after the 1971 season to replace wiring and concrete, rebuild clubhouses, and repaint.41 Another article before the 1973 season noted $27,000 in offseason improvements made to the ballpark, including box seat replacements.42 Later in the decade, public debate over replacing the park began to gain momentum, especially as other Triple-A cities built new parks or renovated old ones. IL President Harold Cooper, on a visit to Rochester in 1978, warned: “Let’s face it, Silver will not last forever. Through the years we have found that spending money to patch up an old plant is throwing money away.”43

Patching up the old plant remained the preferred approach through the 1980s. A renovate-vs.-build debate racked the board of directors of Rochester Community Baseball for several years until renovation won out.44 A massive electronic scoreboard was added in right-center field for the 1982 season. The Wings’ 1983 yearbook detailed extensive improvements, including a new roof, press box upgrades, major concrete restoration, and the replacement of bleacher seats and field lighting. (The yearbook also hinted at problems still unsolved, including water lines that delivered rusty water and an unpaved parking area likened to a “dust bowl.”)

All of this was a prelude to a $4.5 million project that gutted and renovated the old ballyard in the 1986-1987 offseason. The ambitious schedule required the work to be completed over a Rust Belt winter, and the project team discovered early on that no plans for the original stadium could be found. Still, the overhaul was finished in time for Opening Day in April 1987. Improvements included the installation of 240 tons of new support steel, new grandstand seats, expanded clubhouses, new umpires’ quarters, increased storage, upgrades to concessions areas, new bathrooms, a wine and beer garden, a new box office, and regrading and oiling of the still-unpaved westside parking lot. The small army of laborers included Red Wings pitcher Phil Huffman, temporarily employed by an electrical contractor.45

Noteworthy events continued at Silver throughout the 1970s and 1980s. A slimmed-down version of the New York Yankees came to town in June 1971 to play the IL All-Stars. The All-Stars won 15-13 on a home run by Rochester’s Bobby Grich in front of 11,000 fans.46 The park hosted many memorable pre-game happenings as well. These included performances by the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra, a high-wire walk by Karl Wallenda, a home-run contest featuring Mickey Mantle between games of a doubleheader, a softball game featuring TV soap opera stars, and the wedding at home plate of Red Wings catcher Tim Derryberry. Also on hand was organist Fred Costello, hired in 1977, who, as of 2020, has punctuated baseball action in Rochester for more than 40 years.47

Then there was the concert scene, which developed after the demolition of Holleder Stadium in 1985. Silver hosted its first major rock concert that year — a four-band bill headlined by Foreigner, whose lead singer, Lou Gramm, was a Rochester native. Van Halen, U2, the Grateful Dead, and a Metallica/Aerosmith double bill followed over the next five years. In 1988, Silver also hosted an eight-day religious gathering when the Rev. Billy Graham brought one of his crusades to Rochester.

The Red Wings’ 1989 game program and yearbook lists a variety of community events at Silver, including a first-ever arts and crafts festival, a Puerto Rican festival, and high school and Little League games. Generations of Rochester-area schoolboy ballplayers got to tread Silver’s grass as part of tournament action, including left-handed pitcher Mike Jones. Jones first played at Silver Stadium in the 1970s as a schoolboy star for Pittsford Sutherland High School. He returned as a professional for several teams, including the hometown Red Wings, in between parts of four major-league seasons with the Kansas City Royals.48

The new beginning promised by the 1986-1987 renovation turned out to be a temporary lease on life. A news report in spring 1992 noted that Silver remained deficient in several key areas, with no skyboxes, poor outfield drainage, and “among the worst lighting” of any Triple-A park. A shortage of parking came to be seen as a shortcoming as well, though it had long benefited neighborhood residents, who rented space on their lawns to cars.49 Some fans also viewed the nearby neighborhood as unsafe. The renovation failed to increase attendance — perhaps, club officials suggested, because the team did not budget enough to promote it. Further, new minor-league stadium codes created by Major League Baseball would have required Rochester Community Baseball to plow another $1 million into stadium upgrades by 1994.50 In June 1992, Rochester Community Baseball president Elliot Curwin said at a public forum: “We can’t survive at Silver Stadium.”51

A study commissioned by a group of local business owners in 1991 recommended a new open-air stadium to help revive Rochester’s downtown. After considerable back and forth, local leaders backed a stadium site on Oak Street downtown in May 1993. Rochester Community Baseball signed on to that site the following month. State funding was promised, withdrawn, then restored. Construction on the new park, Frontier Field, began in July 1995 and was completed a year later. The Red Wings’ 68th season in Silver Stadium, in 1996, was to be their last.52

The final regular-season game at Silver drew 12,756 fans on August 30, 1996, the park’s largest crowd in 15 years. Just like the first game, the Red Wings took the loss, this time an 8-5 defeat at the hands of the Ottawa Lynx.53 The final game ever at the park was yet another loss — a 10-5 playoff defeat September 10 to the Columbus Clippers in front of 5,573.54 Designated hitter Drew Denson made the final out, grounding to third base. After baseball, Silver hosted a handful of events, ranging from an outreach event for homeless veterans55 to a concert by George Clinton and Parliament-Funkadelic.56 While Clinton and company tore the roof off the stadium metaphorically, it wasn’t torn off literally until January 1998, when demolition began.57 The former site of Silver Stadium is now an office and industrial park known as Excel Industry Park.58 A plaque at the site honors the stadium’s decades of baseball history.

Lamenting the cold, rainy weather on Opening Day back in 1929, longtime Rochester journalist Henry W. Clune mused, “If we only get some sun, it will be great fun to sit in those new stands with a bag of peanuts, a stub pencil and a score card and watch the good Red Wings do their stuff.”59 Sun in Rochester can be a hit-or-miss proposition, but for 68 years, the city’s baseball fans found plenty of fun and excitement in all weather in the stands of Red Wing/Silver Stadium.

Last edited: January 15, 2021 (ghw)

Acknowledgments

This story was reviewed by Malcolm Allen and Phil Williams and fact-checked by Karen Holleran.

Sources

In addition to specific sources cited in the Notes, the author also obtained information from baseball-reference.com and retrosheet.org; from the Rochester (New York) Democrat and Chronicle; and from Rochester Red Wings game programs and yearbooks from 1982 to 1994.

For information on the Negro Leagues and Rochester, see:

Lanctot, Neil. Negro League Baseball: The Rise and Ruin of a Black Institution (Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004), especially pages 328, 335, and 338.

Notes

1 The International League was a Double-A league from 1912 to 1945. It became a Triple-A circuit in 1946 when the highest minor league designation changed from Double-A to Triple-A. The league had been renamed in 1912. Prior to that, it was known as the Eastern League. Rochester was a charter member of the Eastern League in 1892.

2 Several sources including Larry Bump, “United Effort Needed for New Stadium,” Rochester (New York) Democrat and Chronicle, April 16, 1979: 2E.

3 The $300,000 figure is quoted in several news stories from 1926 and successive years, including “Construction of New Concrete Baseball Stadium in Norton Street Lot to Be Started Immediately,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, November 17, 1926: 19. The “almost $400,000” figure is from Joseph T. Adams, “Red Wings Will Open Home Season and Stadium Today,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, May 2, 1929: 1.

4 Henry W. Clune, “Many Ducks See Opener,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, May 3, 1929: 1.

5 Photos accessed online November 2020.

6 “Wing Park One of Minors’ Finest,” Rochester (New York) Times-Union, May 1, 1957: 60.

7 Dave Warner, “It’s Wings 7-5, Despite Foe’s Record Homer,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, July 12, 1964: 1D.

8 Greg Boeck, “Fuller Hits 3 Homers in Wings’ Romp,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, June 8, 1976: 1D. This story puts the scoreboard’s height at 45 feet and the distance at 415 feet.

9 Joseph T. Adams, “Reading Beats Red Wings Before 15,000,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, May 3, 1929: 1.

10 Capacity figures taken from Rochester Democrat and Chronicle pre-season preview articles and Red Wings game programs and yearbooks. The 1987 Red Wing yearbook and game program mentions that seating capacity decreased following the renovation, as the club attempted to provide larger, roomier seats.

11 Joseph T. Adams, “Record Crowd of 19,006 Sees Wings Lose Opener to Bears,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, May 6, 1931: 1.

12 According to Rochester Democrat and Chronicle reports, the Grateful Dead in 1987 and 1988 and U2 in 1987 all attracted sellout crowds. However, the paper listed the Dead’s 1987 turnout at 30,100 and called it the largest crowd in stadium history, while characterizing the subsequent U2 and 1988 Dead crowds as 30,000. It’s not clear from the reports why the Dead’s 1987 crowd would have been larger than the other two. The Rochester newspaper also credited Rev. Billy Graham with drawing 144,000 people to his eight-day Crusade in 1988, but listed his top one-day attendance at about 23,000.

13 Bob Matthews, “Thanks for the Silver Memories,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, August 30, 1996: 7D.

14 “Station WHEC to Broadcast Ball Games,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, April 20, 1928: 24.

15 “Gunnar O. Wiig, First Voice of Wings,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, April 14, 1970: 4B. Wiig’s granddaughter Kristen, born three years after his death, went to high school in the Rochester suburb of Brighton. She gained fame in the 21st century as a cast member of the longstanding TV comedy show Saturday Night Live.

16 “Buck Named Cards ‘Voice,’” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, February 6, 1954: 17.

17 Event advertisement, Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, September 7, 1930: 8A.

18 Bill Beeney, “Pittsburgh Grays Beat Eagles in Negro Tilt, 5-0,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, August 3, 1938: 23.

19 “Antonelli Goes Thursday Night Before Scouts,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, June 13, 1948: 2D. Also, Associated Press, “Young Southpaw Proves Himself,” Rapid City (South Dakota) Daily Journal, June 18, 1948: 9.

20 “Red Smith Dies at 90,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, August 26, 1975: 2D.

21 “Wing Tips,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, September 2, 1978: 2D.

22 Scott Pitoniak and Jim Mandelaro, “Smith, Nill True Red Wings Fans,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, June 28, 1995: 1D.

23 “Negro League to Play Here; Taylor Named,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, March 13, 1948: 16. The story also noted that Robert Taylor, a leader in Rochester’s Black community, had been named the team’s general business manager.

24 The Brooklyn Dodgers (in 1947) were the pacesetter in the integration of Black talent into the major leagues.

25 Scott Pitoniak, “Powerful ‘Mule’ Rivaled Gibson and Babe,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, July 30, 2006: 1D. Information on the team’s season record taken from Seamheads.com.

26 “Thanks for the Silver Memories.”

27 Bob Matthews, “RBI-Machine Delgado Chasing Hack Wilson’s 191,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, June 15, 2003: 3D.

28 “Thanks for the Silver Memories.”

29 Jack Slattery, “Ross Virgo Gains Unanimous Decision Over Pellone for 16th Victory in Row,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, September 8, 1949: 28. Basilio later lived in the Rochester area, working for the city’s Genesee Brewery. He died in Rochester in November 2012.

30 Event advertisement in Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, August 26, 1954: 14. In a 1977 interview with the same newspaper, Chuck Mangione — by then famous for his flugelhorn playing, composing and arranging — looked back fondly at his days providing pre-game entertainment at the ballpark.

31 “Evacuation of 400 Termed Successful by Top CD Officials,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, July 17, 1955: 1B.

32 George Beahon, “Community Ownership Seen Wings’ Only Hope,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, October 31, 1956: 28.

33 Jim Castor, “Silver: He Rescued the Red Wings,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, April 27, 1974: B1. Castor reported that the Red Wings lost $12,286 in 1964; Silver improved that to a $1,783 loss the following year and then spearheaded a $161,472 profit in 1966 — the year they out-earned the rest of Triple-A combined.

34 Morrie Silver died in 1974. As of 2020, the Silver family is still actively involved in the management of the team.

35 For 1961, the Cardinals replaced a single Triple-A affiliate in Rochester with two Triple-A teams. One played in Portland, Oregon, while the other split time between San Juan, Puerto Rico, and Charleston, South Carolina.

36 The Most Valuable Players during this period were Mike Epstein (1966), Merv Rettenmund (1968), Roger Freed (co-winner, 1970), Bobby Grich (1971), Jim Fuller (1973), Rich Dauer (co-winner, 1976), Craig Worthington (1988), and Jeff Manto (1994). The Most Valuable Pitchers were Dave Leonhard (1967), Roric Harrison (1971), Dennis Martinez (1976), Mike Parrott (1977) and Mike Mussina (1991).

37 Palmer’s only appearances as a Red Wing were made during rehabilitation assignments in 1967 and 1968. He pitched poorly for the Red Wings: In four starts, he pitched 11 innings, giving up 16 hits and 15 earned runs.

38 “Series with Jacksonville Due to Open Tonight — IF,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, July 28, 1964: 1D.

39 Associated Press, “Buffalo Shuffles Game Aside After Protests,” Miami Herald, July 20, 1969: 2F.

40 Associated Press, “Fire Destroys Syracuse Ball Park,” Elmira (New York) Star-Gazette, May 15, 1969: 39. Despite initial predictions that the ballpark was a total loss, the Chiefs managed to make sufficient repairs to return to the stadium later that season.

41 Al C. Weber, “’Lucky’ Steinfeldt Named Triple-A Exec of Year,” The Sporting News, December 4, 1971: 34.

42 “Batter Up!,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, April 24, 1973: 8A.

43 Bruno Sniders, “IL’s Cooper Swings Away,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, February 7, 1978: 1D. Cooper had recently been involved in an extensive renovation of the Triple-A park in Columbus, Ohio.

44 Patti Singer, “Silver’s Tarnished Image,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, March 29, 1992: A1.

45 All information on the 1986-1987 renovation taken from the Red Wings’ 1987 game program and yearbook.

46 Jim Castor, “Stars Outslug Yanks 15-13,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, June 25, 1971: D1. According to the paper, Yankees who were not present for the trip to Rochester included Mel Stottlemyre, Stan Bahnsen, Lindy McDaniel, Thurman Munson, Roy White, and Felipe Alou.

47 As of this writing in December 2020, Costello was still active as the Red Wings’ organist.

48 Joe Robbins, “Jones Returns Home to Pitch For Red Wings,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, February 9, 1989: 1D.

49 Alan Morrell, “Whatever Happened To … Silver Stadium?,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, April 4, 2019. Accessed online December 8, 2020.

50 “Silver’s Tarnished Image.”

51 “Frontier Evolution,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, April 6, 1997: 26.

52 Ibid.

53 Jim Mandelaro, “For Silver, Service Ends,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, August 31, 1996: 1D.

54 Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, September 11, 1996: 5D.

55 Jack Jones, “Homeless Vets Get a Treat,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, October 27, 1996: 1B.

56 “Event of the Day,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, October 20, 1996: 1C.

57 “Demolition of Silver Stadium to Begin Today,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, January 21, 1998: 1B.

58 Brian Sharp, “Development Ideas Sought for Three Areas in Rochester,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, November 29, 2019: 2A.

59 Clune.